Abstract

Experiencing emotions is a complex process that varies across social contexts (e.g., culture) and over time. The current research examined the levels and trajectories of self-reported emotions among US (n = 321) and Japanese (n = 388) adolescents (age range: 11–14 at Time 1). Emotions were conceptualized as high arousal positive (HAP), low arousal positive (LAP), high arousal negative (HAN), and low arousal negative (LAN). At each time point, US adolescents (vs. Japanese) showed greater positive and lower negative emotions (both arousal levels). Positive and negative emotions were negatively associated in the US, but the associations were not present or were positive in Japan. While US adolescents’ HAP and LAN emotions remained stable, Japanese adolescents showed increases in HAP and LAN emotions over time. However, both groups showed increases at similar rates for HAN and no change in LAP emotions. Collectively, findings suggest that emotions are both pancultural and culture-specific and highlight the value of considering valence and arousal in cross-cultural examinations of emotions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Extant literature on emotions has shown marked cross-cultural differences between Western (e.g., North American) and East Asian contexts in display rules (e.g., Eid & Diener, 2001; Matsumoto & Hwang, 2012) and the coexistence of positive and negative emotions (e.g., Miyamoto et al., 2017). As cultures differ in their valuation (e.g., Senft et al., 2023; Tamir et al., 2016) and conceptualizations of emotions (e.g., Uchida & Kitayama, 2009), the development of individuals’ emotional experiences and expression likely differ across cultural milieus. During early adolescence, emotional experiences and expression may be particularly sensitive to social constraints and norms regarding emotional processes (Blakemore & Mills, 2014). These variations are in part attributable to cognitive and neurophysiological changes including puberty (Dahl et al., 2018), as well as ecological changes, such as changes in interpersonal relationships and school transitions (Juvonen, 2007). As such, early adolescence is a ripe period for investigating changes in emotional processes longitudinally and cross-culturally. Nonetheless, there is a paucity of cross-national research on emotional experiences during adolescence. Given the differential values attached to emotions across cultures, Tsai and colleagues maintain that both valence (i.e., pleasure) and arousal (i.e., activation) dimensions should be considered (Tsai et al., 2006). By tracking adolescents’ emotional experiences across 18 months, the current research aimed to understand variability in the valence and arousal levels of emotional experiences among adolescents in Japan and the United States.

Emotions in sociocultural contexts: considering valence and arousal

From a functionalist view of emotions, emotion-related goals are largely guided by and nested in a sociocultural context, suggesting that culture may play a significant role in emotional processes (Mesquita & Boiger, 2014). Given that emotions serve social functions and incite behavioral tendencies that maximize goal progress (Lench et al., 2016), goals that vary by culture and culturally accepted displays of emotion may make different emotions more or less prevalent (Boiger et al., 2013) in different cultures. Studies in adults have found that emotional regulation (Ma et al., 2018), desired emotions (Tamir et al., 2016), and valuation of emotions (Tsai et al., 2006) vary across cultures. Higher levels of self-reported positive emotions have also been found in Western cultures, while higher levels of negative emotions are more readily evident in Eastern cultures (e.g., Soto et al., 2005). In line with these findings, there is evidence that positive emotions are valued to a greater extent in Western cultural contexts (e.g., Sims et al., 2015), and negative emotions are deemed more undesirable (e.g., Bastian et al., 2012). Furthermore, positive and negative emotions are often viewed as naturally coexisting (i.e., dialectical beliefs) in East Asian cultures, while they tend to show an inverse relation in Western contexts (Miyamoto et al., 2017).

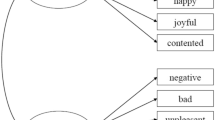

In studies of emotions across cultures, the circumplex model (Russell, 1980) may bear importance. Emotional experiences can be understood based on valence (positive or pleasant to negative or unpleasant) and arousal (high arousal to low arousal). This conceptual model yields four quadrants of affect by intersecting two dimensions: high arousal positive (HAP), low arousal positive (LAP), high arousal negative (HAN), and low arousal negative (LAN) emotions. Researchers argue that most emotions can be mapped on the intersections between these two orthogonal neurophysiological systems (hedonic tone and alertness) and that this dimensional approach provides a useful framework in understanding emotions (Nook et al., 2017; Posner et al., 2005). Moreover, the circumplex model has been widely evaluated in empirical research utilizing various methodologies including self-report (Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2016), across age groups (e.g., Nook et al., 2017), and cultural groups (Sims et al., 2015). Research indicates that the valuation of HAP emotions, such as excitement, is higher among European and Asian Americans when compared to Chinese in Hong Kong, and of LAP emotions, such as calmness, is higher among Asian Americans and Chinese in Hong Kong (vs. European Americans; Tsai et al., 2006). Differences emerge within negative emotions as well. For example, the expression of anger is deemed more acceptable in the US, whereas other negative emotions, such as shame, are more acceptable to express in Japan (Boiger et al., 2013).

Emotional experiences during early adolescence

Adolescence is an important developmental period to investigate the role of sociocultural contexts on emotions. During this period, emotional experience and expression may be particularly responsive to their sociocultural influences, such as display rules and social partner’s emotions (Blakemore & Mills, 2014). Yet, our understanding of emotional processes of adolescents is still limited, as a substantial body of research on this topic has been conducted in Western countries (Raval & Walker, 2019). Given that social agents and the sociocultural milieu become increasingly important during adolescence, it is important to understand whether culturally variant patterns in emotions observed in adulthood would hold during earlier developmental stages.

Transitioning into adolescence, children in Western cultures generally show heightened negative emotions and fluctuations (Larson et al., 2002; Reitsema et al., 2022), as well as increases in internalizing problems related to negative emotions (e.g., depression; Shorey et al., 2022). Yet, there is mixed evidence regarding the trajectories of negative emotions, and little is known regarding early adolescents’ experiences of positive emotions over time (Booker & Dunsmore, 2017). A recent meta-analysis revealed that negative emotions are more prevalent among adolescents compared to children, while positive emotions and happiness stay relatively stable across the developmental stages (Reitsema et al., 2022). However, this research was limited in that all study samples meta-analyzed were European or North American children and adolescents. Despite cross-national research focusing on the differences in expression and experience of emotions in adulthood (e.g., Sims et al., 2015; Tsai et al., 2006), there is scant cross-national research attending to changes in emotions in adolescence.

Notably, no research to date has examined early adolescents’ emotional experiences as varied by both valence and arousal. With cognitive development, adolescents become able to differentiate emotions that map onto the circumplex model, an extension of the dichotomy (i.e., good vs. bad feelings) understood in earlier developmental periods (Posner et al., 2005). Nook et al. (2017) suggest that with increasing verbal knowledge from childhood to adolescence, children’s emotion representations expand from a valence dichotomy to a circumplex model. Taken together, this period is ripe for an investigation into the changes in emotional experience that vary by time, nation, valence, and arousal level.

Current study

The current research examined the longitudinal patterns of adolescents’ emotional experiences across the US and Japan, guided by four goals. First, given that scant research has examined adolescents’ emotions based on the circumplex model, we aimed to fill this gap by evaluating four dimensions of emotions derived from the circumplex model of emotions, which includes both valence and arousal levels. Second, we focused on early adolescence, which broadly encompasses the age range of 10 to 14. During this developmental period, adolescents undergo a host of ecological changes and accompanying changes in emotion dynamics, yet studies focusing on their trajectories over time are lacking (Reitsema et al., 2022). Third, building upon the cross-national research on similarities and differences in adults’ emotions (e.g., Boiger et al., 2013), we focused on the US and Japan. While we note substantial within-country variability in emotions, we aimed to delineate the patterns of adolescents’ emotions at the country level, as emotions are socialized within a cultural context. Lastly, in assessing emotions, we utilized adolescents’ subjective reports of their global experiences of emotions. As self-evaluated emotional experiences are under the influence of cultural constraints, such as shared cultural norms (Matsumoto & Hwang, 2012), we anticipated that subjective reports would allow us to detect potential variations in emotions driven by cultural impact.

Given the greater prevalence of dialectal beliefs about emotions (e.g., Miyamoto et al., 2017), we hypothesized that the correlation between positive and negative emotions would be stronger in Japan than in the US. However, as scant research has investigated associations between co-occurring arousal levels (HAP and LAP or HAN and LAN) of adolescents, we made no a priori hypothesis about this association. We also anticipated possible differences in mean levels of HAP, LAP, HAN, and LAN emotions in the two countries. Based on findings from cross-cultural research among adults (e.g., Soto et al., 2005), we anticipated that US adolescents would report greater levels of HAP and LAP, and Japanese reporting greater levels of HAN and LAN. Regarding the growth trajectories, we anticipated increasing negative emotions and decreasing positive emotions, at least in the US, based on prior research (e.g., Larson et al., 2002). Owing to the lack of prior research, no a priori hypothesis was specified regarding the cross-national differences.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from the [Masked], a cross-national study focusing on adolescents’ emotional and academic adjustment. The study spanned 18 months, with data collected at three evenly spaced time points. The US adolescents were recruited from inland Southern California. Demographic information of the entire student body from which the participants were recruited was made publicly available by the school districts. Hispanic-Latino Americans made up the largest portion of the study body with 47% identifying as such. Next, 23% of the student body were European American, 17% were African American, 8% were Asian American, and 5% were multi-race or unknown. Students came from 2 school districts in which the average household incomes were $67,703 and $77,439 (United States Census Bureau, 2017). The Japanese participants were all native Japanese adolescents recruited from two cities in the western part of Japan. The average household income in the two cities was ¥428,440 and ¥507,449 (i.e., $46,981 and $55,645; Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2018).

Adolescents in both countries completed surveys at three times, and each time point was approximately six months apart. The total sample included 321 US (191 girls) and 388 Japanese (210 girls) adolescents. All participants were between 11 and 14 years old at the beginning of the study. For 36% of the participants in the US and 87% in Japan, data were available for all variables across all three time points, with 72% in the US and 96% in Japan providing data for at least two time points. Adolescents with no missing data across the three time points reported lower HAP and LAP emotions, compared to those with incomplete data at Time 2 and Time 3 (ts > 2.53, ps < 0.05). Dummy codes were assigned to participants with complete and incomplete data, and that variable was entered as a predictor for assessing the missing data mechanism. Patterns of missingness were analyzed using Little’s (1988) procedure. Results indicated that all data were missing completely at random, χ2 (68, N = 709) = 75.87, p = 0.240. As such, full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was employed to handle the missing data.

Procedure

US adolescents were recruited from one summer program in one school district and four middle schools in another school district. To qualify for participation, students must return a consent form signed by their parents or guardians, and a personal assent form. At each of the three time points, participants completed a survey in school. In each country, trained researchers were present to assist with the data collection. In the US, a small portion (12%) of the participants completed the surveys at home or online. Adolescents in Japan were recruited from two middle schools. The school principals granted their consent. Trained research assistants and the homeroom teacher assisted with the data collection in the classroom. Participants in both countries received a $5 gift card for completing each survey. Approval for the research procedures was obtained from the institutional review boards of the University of California, Riverside and Kyoto University.

Measures

The measures used in the present study were originally created in English. Following the recommendation by Brislin (1980), the translation team comprised two native speakers from each country and two bilingual experts who are fluent in both languages. They first translated the measures into Japanese and then back-translated the Japanese version into English. An iterative process was used: the bilingual experts were responsible for translation and back-translation, while the native speakers reviewed and verified the accuracy of the translations.

To assess adolescents’ emotional experiences, a 34-item measure derived from Diener et al. (1995) and Watson et al. (1988) was used. Participants reported on the extent to which they had experienced certain discrete emotions (e.g., happy, calm; see Table S1 for the full list of items in both English and Japanese) during the week prior to their completion of the survey (1 = never, 5 = very often). Following past research (e.g., De Dreu et al., 2008), the items were categorized into four dimensions of emotions (HAP, LAP, HAN, and LAN), each comprising two to five items, based on valence and arousal level (see Table 1). To ensure the validity of this factor structure in the US and Japan, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis. A four-factor model in which each emotion dimension was specified by the corresponding items was tested for each country. In the US, the model fit the data well (CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.058, SRMR = 0.047); in Japan, the model showed an acceptable fit (CFI = 0.86, TLI = 0.82, RMSEA = 0.085, SRMR = 0.082). For each emotion dimension, composite scores were derived by calculating the mean of the corresponding items within each dimension. A summary of the selected items for each dimension, means, standard deviations, and reliability is presented in Table 1. To test for equivalence of the measure across the US and Japan, we employed the alignment method (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014). Results indicated supported the equivalence at the metric level, thereby allowing for meaningful comparisons between the two countries (see Supplementary Information).

Analytic plan

To evaluate the study hypotheses, we first evaluated the associations among the four emotion dimensions, zero-order correlation analysis was conducted at each time point, with attention to possible differences between the two countries. Next, we examined the intercepts (means) and growth trajectories (rate of change over time) of adolescents’ emotional experiences in the US and Japan. Two-group growth-curve analysis was conducted in the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) framework using Mplus 7.31 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2012).

Results

Associations among the four dimensions of emotion

Table 2 presents the correlations among emotion dimensions in the US and Japan at each time point. To test between-country differences in the magnitude of the associations among the emotion dimensions, we used Fisher’s r-to-z transformations. In both countries, results showed positive associations between HAP and LAP emotions at all time points (rs ranged from 0.38 to 0.43 in the US and 0.42 to 0.44 in Japan, ps < 0.001), as well as between HAN and LAN emotions (rs ranged from 0.61 to 0.69 in the US and 0.57 to 0.61 in Japan, ps < 0.001). However, while HAP emotions and HAN emotions were negatively correlated at all time points among US adolescents, these relations either were not significant or were in the opposite (i.e., positive) direction for Japanese adolescents, and correlation difference test based on Fisher’s transformations revealed that this pattern was significantly different between countries (see Table 2). Similarly, US adolescents’ HAP emotions were negatively correlated with LAN emotions at all three time points, whereas this correlation was not significant for Japanese adolescents. Notably, at Times 1 and 2, Japanese adolescents’ LAP and HAN emotions were positively correlated, whereas this association was negative for US adolescents. In a similar vein, Japanese adolescents’ LAP emotions were positively correlated with LAN at all three time points, but these associations were negative in the US, as shown in significant correlation difference tests. To test whether the correlations differed across time within each country, nested models were evaluated. To this end, models with equality constraints placed on pairs of correlations across time points were compared to their corresponding unconstrained models where all parameters were set to be freely estimated. In general, within each country, the sizes of the correlations were stable across time points (see Table 2).

Averages and changes in adolescents’ emotions over time

To assess both the levels and how American and Japanese adolescents’ emotional experiences change over time, growth curve models were evaluated. For each dimension of emotion (HAP, LAP, HAN, and LAN), a latent intercept-slope model was specified. The intercept represented the initial levels of adolescents’ experiences of each emotion category (i.e., emotional experiences at Time 1), while the slope represented the change rate of the corresponding emotions from Time 1 to Time 3. Using nested model comparison in SEM, comparisons were made between the unconstrained and constrained models. In the unconstrained models, all parameters were freely estimated. In the constrained model, between-country equality constraints were imposed on the parameters (i.e., intercept and slope). A significant chi-square difference (∆χ2) between an unconstrained and a more parsimonious model (i.e., a constrained model) suggests a between-country difference in the corresponding parameter. To achieve parsimony, gender was included in the model only when it was significantly associated with the intercept or slope of the predicted emotion dimension. Based on this criterion, gender was included as a predictor of the intercepts of every emotion dimension, as well as the slope of LAP only. Results from the nested model comparisons are shown in Table 3.

High Arousal Positive (HAP) emotions

For the trajectories of HAP emotions (i.e., happy, excited), the unconstrained model fit the data well, χ2(10) = 12.98, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.03. When the intercept was constrained between the two countries, the model exhibited a significantly poorer fit than the unconstrained model, ∆χ2(1) = 7.64, p = 0.006, indicating that the initial levels of HAP differed in the two countries. As shown in Table 4, US (vs. Japanese) adolescents reported experiencing more HAP emotions at Time 1. The model with the slope coefficient constrained between the two countries also fit significantly worse than the unconstrained model, ∆χ2(1) = 6.69, p = 0.010, indicating that the trajectories were different between the two countries. As shown in Fig. 1 (Panel A), while US adolescents’ HAP remained relatively stable (γ = -0.05, ns), adolescents in Japan showed an increase in HAP emotions over time (γ = 0.07, p = 0.013).

Low Arousal Positive (LAP) emotions

For LAP emotions (i.e., calm, relaxed, peaceful), the unconstrained model fit the data well, χ2(8) = 11.39, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.04. When the intercept was constrained between the two countries, the model fit became significantly worse than the unconstrained model, ∆χ2 (1) = 13.88, p < 0.001. As shown in Table 4, US (vs. Japanese) adolescents reported experiencing more LAP emotions at Time 1. However, the model with the slope coefficient constrained fit equally well as the unconstrained model, ∆χ2(1) = 1.87, ns. As shown in Fig. 1 (Panel B), in both countries, adolescents’ LAP emotions remained stable over time (γs = -0.10, ns).

High Arousal Negative (HAN) emotions

The unconstrained model of HAN emotions (i.e., ashamed, worried, afraid, guilty, angry) fit the data well, χ2(10) = 8.18, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.01, RMSEA = 0.00. When the intercept was constrained between the two countries, the model fit was significantly worse than the unconstrained model, ∆χ2(1) = 28.62, p < 0.001. As presented in Table 4, Japanese (vs. US) adolescents reported experiencing more HAN emotions at Time 1. Yet, a model with the slope coefficient constrained fit equally well as the unconstrained model, ∆χ2(1) = 0.95, ns. As shown in Fig. 1 (Panel C), adolescents from both countries showed similar increases in HAN emotions over time (γs = 0.08, ps < 0.001).

Low Arousal Negative (LAN) emotions

The unconstrained model of LAN emotions (i.e., depressed, sad, tired) fit the data well, χ2(10) = 16.67, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.04. When the intercept was constrained between the two countries, the model fit was significantly worse than that of the unconstrained model, ∆χ2(1) = 65.76, p < 0.001. As presented in Table 4, Japanese (vs. US) adolescents reported more LAN at Time 1. The model with the slope coefficient constrained also fit significantly worse than the unconstrained model, ∆χ2(1) = 4.97, p = 0.026. As shown in Fig. 1 (Panel D), Japanese adolescents’ LAN emotions increased over time (γ = 0.13, p < 0.001), while US adolescents’ LAN emotions remained relatively stable (γ = 0.03, ns).

Discussion

Utilizing a longitudinal design and cross-national samples from the US and Japan, the present study investigated the changes in early adolescents’ emotional experiences as varied by valence and arousal levels. In line with past research among adults (e.g., Sims et al., 2015), we found an inverse relationship between cross-valenced emotion dimensions (e.g., HAP and HAN, LAP and LAN) among US adolescents. This pattern was not evident among Japanese adolescents. Our findings also show that Japanese adolescents reported higher levels of HAN and LAN, while their US counterparts tended to report higher levels of HAP and LAP. In addition, increases in HAP and LAN over time were evident among Japanese adolescents, while the growth trajectories of these emotion dimensions remained relatively stable for US adolescents. Our analysis also revealed that HAN increased over time in both countries, while the levels of LAP were stable over time in both groups. Taken together, findings from the current study highlight the merits of utilizing the circumplex model in investigating adolescents’ emotional experiences across cultures.

Co-occurrence of emotions: valence and arousal

Our results indicated that between-country differences exist in the associations among every combination of emotion dimensions, except for the within-valence relations (i.e., HAP and LAP; HAN and LAN). In US adolescents, high arousal emotions of differing valences were negatively correlated at all time points (i.e., HAP and HAN; e.g., excitement and anger), whereas for Japanese adolescents, the associations were either absent or in the positive direction. Similarly, while US adolescents showed negative associations between low arousal emotions of differing valences (i.e., LAP and LAN; e.g., calmness and sadness), this relationship was positive at all time points in their Japanese counterparts. Research indicated that maximizing positive emotions is a common practice in Western cultures, dialectical thinking is more readily observed in East Asian cultures (Miyamoto et al., 2017; Sims et al., 2005). Hence, positive and negative emotions tend to co-occur to a greater extent in East Asian countries (i.e., Japan) than in Western countries (i.e., the US; Miyamoto et al., 2017). Replicating prior research among adults, our findings suggest that the co-occurrence of positive and negative emotions may be more common in Japan (vs. the US) in adolescence.

Notably, our findings showed that in Japanese adolescents, emotions crossing both valence and arousal levels co-occurred (i.e., HAP and LAN, LAP, and LAN). US adolescents, on the other hand, showed inverse relations between HAP and LAN and LAP and LAN. These findings suggest that cross-valenced or dialectical emotions are more readily observed among Japanese adolescents (e.g., happiness and sadness; calmness and anger). As such, based on the circumplex model, findings from this research further indicated that in Japan, mixed emotions may occur in all combinations of valence and arousal. This pattern corroborates with Sims et al.’s (2015) work on American and Chinese adults, showing the cooccurrence of cross-valenced emotions with different arousal levels. Interestingly, among Japanese adolescents, stronger cross-valence associations with negative emotions were found in LAP than in HAP, suggesting a greater co-occurrence between negative and LAP emotions. This finding suggests that positively valenced emotions may have differential relationships with negative emotions across the arousal levels, further denoting the value of the nuanced approach using the circumplex model.

Differences in emotional experiences between US and Japanese adolescents

Our assessment of changes in adolescents’ emotions revealed that US adolescents showed higher levels of both positive emotion dimensions at the beginning of the study, compared to their Japanese counterparts. In contrast, the levels of both negative emotion dimensions were higher among adolescents in Japan than in the US. Such findings are consistent with cross-cultural research indicating that individuals in Western (vs. East Asian) cultural environments value and report the experience of positive emotions to a greater extent (e.g., Campos & Kim, 2017; Sims et al., 2015). These findings are also in line with cross-cultural research that showed that US (vs. Japanese) individuals perceive negative emotions as more undesirable (e.g., Curhan et al., 2014). Given that subjective emotional experiences are guided by cultural values attached to emotions, our findings support the idea that culturally based norms and beliefs about emotions may affect adolescents’ emotional experiences. According to the affect valuation theory, there might be a differential impact of culture on actual and ideal affect, such that cultural differences in emotions are more pronounced in ideal than actual affect (Tsai et al., 2006). As such, the possibility that self-reported emotions may be partially influenced by affect valuation should be taken into consideration when interpreting the findings.

Trajectories of emotional experiences change over early adolescence

The current research revealed differences and similarities in the growth trajectories of emotions in Japan and the US. In a nutshell, all emotion composites except LAP increased over time in Japanese adolescents, but only HAN increased in US adolescents.

Similarities in the trajectories

In addition to the lack of empirical investigation into adolescents’ positive emotional experiences in general (Booker & Dunsmore, 2017), changes in adolescents’ LAP emotions remain understudied. In contrast with prior research indicating declining patterns in positive emotions in adolescence (e.g., Larson et al., 2002; Reitsema et al., 2022), our study did not find such a downward trajectory in LAP in either the US or Japan. Sallquist and colleagues (Sallquist et al., 2009) suggested that during adolescence, displaying average or low emotional intensity might be preferred, as children learn to regulate their emotions to be attuned to their peer groups. Thus, our findings suggest that adolescents’ maintenance of LAP may be related to their need to adapt to changing peer relationships in this transitional period.

However, that interpretation may only apply to maintaining positive emotional intensity, as we found that HAN emotions increased over time in both countries. Research on European American adolescents has shown that during early adolescence, anger (e.g., Larson et al., 2002) and anger regulation (Hale et al., 2023) present upward trajectories. A recent longitudinal examination of American adolescents found that they regulated anger increasingly more over the 4-year period of study, and that regulating anger was more related to friend/peer emotion socialization that parental socialization. Thus, early adolescence is marked by increasing importance placed on peer relationships, and those relationships, in turn, are valuable for socializing anger regulation (Hale et al., 2023). This is in line with extant literature documenting heightened externalizing behaviors during adolescence (e.g., Deković et al., 2004; Rothenberg et al., 2020), and adolescents’ self-reports that suppressing sadness (but not anger) would increase their negative emotion (Zeman & Shipman, 1997). During this developmental period, adolescents may be confronted with tasks (e.g., achieving self-assertiveness, navigating relational aggression) that can prompt negative activated emotions that function to mobilize the resources needed to overcome those obstacles (e.g., Hale et al., 2023).

Differences in the trajectories

In Japan, there was an increase in HAP emotions over time, while these emotions stayed relatively stable over time for US adolescents. Although speculative, the upward trajectory in HAP emotions among Japanese adolescents may be attributed to their views about adolescence. Compared to Mainland China, adolescents in more “Western” regions (i.e., US, Hong Kong) tend to view early adolescence as a tumultuous period, which may be characterized by the experience of fewer positive emotions and heightened emotionality (Qu et al., 2016, 2020). Given that adolescents’ conceptions of this period may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies, thereby affecting their behaviors (Telzer et al., 2022), it is possible that a view of adolescence as less emotionally fraught contributes to an increase in HAP emotions. Notably, the current US sample has a high representation of Hispanic-Latino Americans. While sharing similar cultural norms (i.e., the general US context) regarding emotions as European Americans, Hispanic-Latino Americans may emphasize the value of positive emotions to an even greater extent (Campos & Kim, 2017). Given that US adolescents showed higher levels of HAP than their Japanese counterparts at Time 1 and that socialization toward maximizing positive emotions occurs early in life among Westerners (Tsai et al., 2007), the stability in HAP among US adolescents may indicate that in the US, children are socialized to value and experience such emotional states and are able to maintain them.

In Japan, LAN emotions increased over time. However, consistent with the evidence on the stability of depressed mood in early adolescents in Western cultural contexts (e.g., Deković et al., 2004; Hale et al., 2023), LAN did not show increases over time in the US. This may be because in Western cultures, LAN emotions are less acceptable and attractive in peer relationships as evidenced by adolescents’ endorsement in the belief that sadness is a feeling that should not be expressed (Zeman & Shipman, 1997). Thus, American adolescents may have learned to suppress LAN sooner than HAN (Hale et al., 2023). As socialization partners (e.g., parents, siblings, peers) of children in the US may be less accepting of LAN, adolescents in our study may have already responded to mounting social pressures to suppress LAN to keep in line with cultural norms (Ding et al., 2021; Hale et al., 2023). As such, our findings imply that in an environment where LAN emotions are believed to be less desirable (US), adolescents may have already experienced upward trends in such emotions and may now more stably experience LAN.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations in this research should be noted. First, because our samples were drawn from select regions in the US and Japan, our samples were not fully representative of the within-country variations of the two countries. Extant research has indicated that in ethnically diverse countries, such as the US, individuals may endorse different cultural values about emotions (Senft et al., 2023). Although there are significant between-country differences in emotions, such as emotional expressiveness and display rules (e.g., Boiger et al., 2013; Matsumoto et al., 2008), future research may benefit from investigating different ethnic subgroups within the country and directly assessing cultural values and identity pertinent to emotional processes. The current research provided initial evidence of the similarities and differences in adolescents’ emotions between countries, but it is unclear which cultural components (e.g., display rules, cultural orientations) may be at play in predicting cross-cultural differences in emotional processes during adolescence. Examining whether different cultural subgroups display similar trajectories in emotional experiences and which cultural values and norms relate to the trajectories of emotion dimensions would further refine our understanding of emotions.

Second, measures in the current research assessed global experiences of emotions and did not capture minute (e.g., daily, weekly) fluctuations in emotions or the changes with age. While the 6-month timeframe in the current study is apt in reflecting longer-term changes in emotional experiences, measuring emotions after an emotionally arousing event or during social interactions may further clarify how emotions are shaped by everyday experiences. To this end, researchers have advocated the use of dynamic methods (e.g., experience sampling method, examining daily fluctuations; Dejonckheere et al., 2022), or investigating situational changes in emotions (Mesquita & Boiger, 2014). Relatedly, the effects of adolescents’ age were not investigated in the current research, as such information was not collected for the US sample. Future research investigating how emotional experiences change in relation to children’s age would inform the dynamic changes in emotions across adolescence.

Third, to further substantiate the current findings as representative of adolescents’ true emotional experience, measures other than self-report should be utilized. For example, physiological measures, such as electrocardiogram, may be used to identify patterns more objectively in sympathetic and parasympathetic activity associated with high and low activation. Additionally, emotional expression in various formats of communication, such as social media platforms, might be a useful tool to investigate adolescents’ emotional experiences in daily lives (e.g., Hsu et al., 2021).

Lastly, although all emotion subscales used in the current research attained measurement equivalence in the two countries, it remains possible that the meaning and implications of emotions can differ. For example, there may be cultural differences in how discrete emotions are understood and experienced. Future research may clarify this issue by using various data reduction approaches (e.g., individual differences multidimensional scaling) and examining how adolescents’ emotion words are mapped onto this model (e.g., Nook et al., 2017). Additionally, caution is warranted in interpreting the levels of emotions, as the implications of emotions for wellbeing are modulated by cultural context. Although Japanese (vs. US) adolescents reported lower positive and greater negative emotions for both arousal levels at all time points, our findings do not imply that they have impaired psychological functioning. Prior work suggests that the consequences of emotions differ across cultures, especially when social consequences are taken into consideration (Boiger et al., 2013). Evidence also indicates that negative emotions predict poor mental health to a greater extent in the US than in Japan (Clobert et al., 2020; Curhan et al., 2014). Hence, to delineate adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment in light of changes in their emotions, comprehensive arrays of assessments (e.g., regulatory skills, emotional differentiations) may be utilized.

Conclusions

This research provides an inroad to understanding pancultural and culture-specific patterns of the changes in subjective emotional experiences during early adolescence. Notably, we conceptualized emotions based on both valence and arousal levels. Corroborating with prior research findings, the current research showed that self-reported positive emotions were more prevalent in the US and that Japanese adolescents tended to experience dialectical emotions to a greater extent. Regarding changes in emotional experiences, both US and Japanese adolescents showed increases at similar rates for high arousal negative emotions and no change in low arousal positive emotions. Taken together, our findings suggest that the consideration of both valence and arousal levels is important in cross-cultural studies of nuanced emotional experiences of adolescents.

Data availability

Deidentified data used in this study can be downloaded via: https://doi.org/10.6086/D1WT25

References

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Multiple-group factor analysis alignment. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21, 495–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.919210

Bastian, B., Kuppens, P., Hornsey, M. J., Park, J., Koval, P., & Uchida, Y. (2012). Feeling bad about being sad: The role of social expectancies in amplifying negative mood. Emotion, 12, 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024755

Blakemore, S. J., & Mills, K. L. (2014). Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 187–207. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115202

Boiger, M., Mesquita, B., Uchida, Y., & Barrett, L. F. (2013). Condoned or condemned: The situational affordance of anger and shame in the United States and Japan. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 540–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213478201

Booker, J. A., & Dunsmore, J. C. (2017). Affective social competence in adolescence: Current findings and future directions. Social Development, 26, 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12193

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Vol. 2. Methodology (pp. 389–444). Allyn & Bacon.

Campos, B., & Kim, H. S. (2017). Incorporating the cultural diversity of family and close relationships into the study of health. American Psychologist, 72, 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000122

Clobert, M., Sims, T. L., Yoo, J., Miyamoto, Y., Markus, H. R., Karasawa, M., & Levine, C. S. (2020). Feeling excited or taking a bath: Do distinct pathways underlie the positive affect–health link in the US and Japan? Emotion, 20, 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000531

Curhan, K. B., Sims, T., Markus, H. R., Kitayama, S., Karasawa, M., Kawakami, N., Love, G. D., Coe, C. L., Miyamoto, Y., & Ryff, C. D. (2014). Just how bad negative affect is for your health depends on culture. Psychological Science, 25, 2277–2280. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614543802

Dahl, R. E., Allen, N. B., Wilbrecht, L., & Suleiman, A. B. (2018). Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature, 554, 441–450. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25770

De Dreu, C. K., Baas, M., & Nijstad, B. A. (2008). Hedonic tone and activation level in the mood-creativity link: Toward a dual pathway to creativity model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 739–756. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.5.739

Dejonckheere, E., Demeyer, F., Geusens, B., Piot, M., Tuerlinckx, F., Verdonck, S., & Mestdagh, M. (2022). Assessing the reliability of single-item momentary affective measurements in experience sampling. Psychological Assessment, 34, 1138–1154. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001178

Deković, M., Buist, K. L., & Reitz, E. (2004). Stability and changes in problem behavior during adolescence: Latent growth analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1027305312204

Diener, E., Smith, H., & Fujita, F. (1995). The personality structure of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.1.130

Ding, R., He, W., & Wang, Q. (2021). A comparative analysis of emotion-related cultural norms in popular American and Chinese storybooks. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 52, 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022120988900

Eid, M., & Diener, E. (2001). Norms for experiencing emotions in different cultures: Inter- and intranational differences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 869–885. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.869

Hale, M. E., Price, N. N., Borowski, S. K., & Zeman, J. L. (2023). Adolescent emotion regulation trajectories: The influence of parent and friend emotion socialization. Journal of Research on Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12834

Hsu, T. W., Niiya, Y., Thelwall, M., Ko, M., Knutson, B., & Tsai, J. L. (2021). Social media users produce more affect that supports cultural values, but are more influenced by affect that violates cultural values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121, 969–983. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000282

Juvonen, J. (2007). Reforming middle schools: Focus on continuity, social connectedness, and engagement. Educational Psychologist, 42, 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520701621046

Larson, R. W., Moneta, G., Richards, M. H., & Wilson, S. (2002). Continuity, stability, and change in daily emotional experience across adolescence. Child Development, 73, 1151–1165. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00464

Lench, H. C., Tibbett, T. P., & Bench, S. W. (2016). Exploring the toolkit of emotion: What do sadness and anger do for us? Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10, 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12229

Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Wormington, S. V., & Ranellucci, J. (2016). Measuring affect in educational contexts: A circumplex approach. In M. Zembylas, P. Schutz (Eds.), Methodological advances in research on emotion and education (pp. 165–178). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29049-2_13

Little, R. J. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

Ma, X., Tamir, M., & Miyamoto, Y. (2018). A socio-cultural instrumental approach to emotion regulation: Culture and the regulation of positive emotions. Emotion, 18, 138–152. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000315

Matsumoto, D., & Hwang, H. S. (2012). Culture and emotion: The integration of biological and cultural contributions. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43, 91–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022111420147

Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., & Fontaine, J. (2008). Mapping expressive differences around the world: The relationship between emotional display rules and individualism versus collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39, 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022107311854

Mesquita, B., & Boiger, M. (2014). Emotions in context: A sociodynamic model of emotions. Emotion Review, 6, 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914534480

Miyamoto, Y., Ma, X., & Wilken, B. (2017). Cultural variation in pro-positive versus balanced systems of emotions. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 15, 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.05.014

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed). Muthén & Muthén.

Nook, E. C., Sasse, S. F., Lambert, H. K., McLaughlin, K. A., & Somerville, L. H. (2017). Increasing verbal knowledge mediates development of multidimensional emotion representations. Nature Human Behaviour, 1, 881–889. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0238-7

Posner, J., Russell, J. A., & Peterson, B. S. (2005). The circumplex model of affect: An integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 17, 715–734. https://doi.org/10.1017/0954579405050340

Qu, Y., Pomerantz, E. M., Wang, M., Cheung, C., & Cimpian, A. (2016). Conceptions of adolescence: Implications for differences in engagement in school over early adolescence in the United States and China. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 1512–1526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0492-4

Qu, Y., Rompilla, D. B., Wang, Q., & Ng, F. F. Y. (2020). Youth’s negative stereotypes of teen emotionality: Reciprocal relations with emotional functioning in Hong Kong and Mainland China. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49, 2003–2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01303-0

Raval, V. V., & Walker, B. L. (2019). Unpacking ‘culture’: Caregiver socialization of emotion and child functioning in diverse families. Developmental Review, 51, 146–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.11.001

Reitsema, A. M., Jeronimus, B. F., van Dijk, M., & de Jonge, P. (2022). Emotion dynamics in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic and descriptive review. Emotion, 22, 374–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000970

Rothenberg, W. A., Lansford, J. E., Bornstein, M. H., Chang, L., Deater‐Deckard, K., Di Giunta, L., ... & Bacchini, D. (2020). Effects of parental warmth and behavioral control on adolescent externalizing and internalizing trajectories across cultures. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30, 835–855. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12566

Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 1161–1178. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077714

Sallquist, J. V., Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., Reiser, M., Hofer, C., Zhou, Q., Liew, J., & Eggum, N. (2009). Positive and negative emotionality: Trajectories across six years and relations with social competence. Emotion, 9, 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013970

Senft, N., Doucerain, M. M., Campos, B., Shiota, M. N., & Chentsova-Dutton, Y. E. (2023). Within- and between-group heterogeneity in cultural models of emotion among people of European, Asian, and Latino heritage in the United States. Emotion, 23, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001052

Shorey, S., Ng, E. D., & Wong, C. H. (2022). Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61, 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12333

Sims, T., Tsai, J. L., Jiang, D., Wang, Y., Fung, H. H., & Zhang, X. (2015). Wanting to maximize the positive and minimize the negative: Implications for mixed affective experience in American and Chinese contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 292–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039276

Soto, J. A., Levenson, R. W., & Ebling, R. (2005). Cultures of moderation and expression: Emotional experience, behavior, and physiology in Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans. Emotion, 5, 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.154

Tamir, M., Schwartz, S. H., Cieciuch, J., Riediger, M., Torres, C., Scollon, C., Dzokoto, V., Zhou, X., & Vishkin, A. (2016). Desired emotions across cultures: A value-based account. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111, 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000072

Telzer, E. H., Dai, J., Capella, J. J., Sobrino, M., & Garrett, S. L. (2022). Challenging stereotypes of teens: Reframing adolescence as window of opportunity. American Psychologist, 77, 1067–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001109

Tsai, J. L., Knutson, B., & Fung, H. H. (2006). Cultural variation in affect valuation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 288–307. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.2.288

Tsai, J. L., Louie, J. Y., Chen, E. E., & Uchida, Y. (2007). Learning what feelings to desire: Socialization of ideal affect through children’s storybooks. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206292749

Uchida, Y., & Kitayama, S. (2009). Happiness and unhappiness in east and west: Themes and variations. Emotion, 9, 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015634

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Zeman, J., & Shipman, K. (1997). Social-contextual influences on expectancies for managing anger and sadness: The transition from middle childhood to adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 33, 917–924. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.917

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the University of California.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YK was involved in developing the hypotheses, performed the data analyses, and drafted the manuscript. SEK also participated in hypothesis development and drafted the manuscript. YT was involved in designing the broader study and collecting data in Japan and helped with manuscript preparation. ELD was involved in developing the hypotheses and manuscript preparation. CC designed the broader study, collected data in the United States, and was involved in developing the hypotheses, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the institutional review board of University of California, Riverside and Kyoto University.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest and the research was conducted in compliance with ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kyeong, Y., Knapp, S.E., Takahashi, Y. et al. US and Japanese adolescents’ emotions across time: variation by valence and arousal. Curr Psychol 43, 6954–6965 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04890-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04890-w