Abstract

Due to the long-term separation from their parents, the physical and mental health development of left-behind children is not optimal. Among many psychological problems, loneliness is the most significant. We searched all publicly published literature related to the loneliness of left-behind children from its establishment to September 30, 2022 in Chinese and English databases. Forest plots and funnel plots were drawn to examine the heterogeneity and publication bias of the included studies, and the loneliness status of left-behind children was analyzed by meta-analysis. A total of 23 studies with 6,678 left-behind children were included in the analysis. The meta results showed that the loneliness level of left-behind children was higher than that of non-left-behind children. Subgroup analysis showed that there was no significant difference in total effect size among different grades. However, different guardian types could affect the loneliness level of left-behind children, for example, single-parent monitoring was associated with lower loneliness than other relative monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With the acceleration of urbanization and economic development, a number of Chinese residents have chosen to migrate for work in order to seek better job opportunities. However, the long-lasting and highly peculiar system in China is a major obstacle to labor mobility, as it strictly restricts people’s entitlement to basic social benefits, which leaves them facing a number of challenges, including health care, education, instability of work, and inability to access services, outside of one’s birthplace; thus, people have to leave their children in their hometown or entrust them to other relatives and guardians (Wang & Pan, 2020). Under this context, the “left-behind children” (LBC) phenomenon has emerged in China. According to the latest definition of the State Council of China, left-behind children are rural children (rural household registrations) younger than 16 years of age who have two migrant parents or one migrant parent and another parent who has no guardianship ability (China, 2016). According to data, there were 6.436 million LBC in China at the end of 2020.

Due to the changes in the family upbringing structure, LBC show lower levels of academic performance, psychological well-being, character building, and other characteristics (Lin, 2003, Liu et al., 2018). (Lempinen et al., 2018) collected data in 1989, 1999, 2005, and 2014 from 3,749 participants and found that 20% of children reported often feeling lonely. At the same time, their physical growth, social interaction, and especially mental health are adversely affected (Zhang, 2014, Wright & Levitt, 2014). They face the common issue of parental absence caused by parents working outside the home for long periods, which breaks the normal family structure and affection. The characteristics of this parental absence often generate considerable negative effects on LBC emotional adaptations (Cheng et al, 2010, Wen & Lin, 2012), such as loneliness, depression, anxiety, and other unpleasant emotions or negative emotions (Cicchetti et al., 2010, Fan, 2011), among which loneliness appears most frequently (Antia et al., 2020).

Loneliness has been described as a perceived deficiency in one’s social relationships and the accompanying emotional distress, such as sadness, emptiness, or longing (Asher, 2003). Loneliness can be divided into emotional and social loneliness (Weiss, 1973, Cosan, 2014, Ditommaso, 1997). Emotional loneliness is marked by the absence of intimate emotional attachment with others; it leaves a feeling of emptiness, longing, and alertness. When children lose their parents as attachment figures, they are at risk of experiencing emotional loneliness (Ouellette, 2004). Loneliness not only affects children’ s cortisol level, sleep quality, and physical health but also often leads to depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline in children and reduces their level of self-esteem and subjective well-being (Liu et al., 2010, Maes et al., 2016), thus influencing their mental health. More severe cases may even lead to suicidal behavior (Simon & Walker, 2018, Mishra et al., 2018). An increasing amount of evidence has shown that LBC is closely related to loneliness, and the loneliness level of LBC is higher than that of non-LBC (NLBC) (Tang et al., 2019, Ren et al., 2017, Ji & Zhuo, 2017). This phenomenon has become a significant social problem and has received extensive attention from the government and media (Zhang, 2010).

Previous meta-analyses focusing on LBC in China suggested that parental migration had negative impacts on children’s mental health; however, there is still a lack of systematic research on the differences in loneliness between LBC and NLBC. Considering the harmful impact of loneliness on the development of LBC, it is crucial to conduct a systematic and comprehensive meta-analysis to synthesize and compare the loneliness status of LBC and NLBC and to gain a better understanding of the current status of LBC mental health. This study uses a meta-analysis to statistically combine the outcomes of several studies in order to explore the relationship between LBC and loneliness and provide a reference for promoting the mental health of LBC.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and study selection

The first author (XY) and the third author (LH) conducted an extensive automated search of electronic articles in the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang, VIP Journals of Chinese Science, PubMed, and Web of Science (Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, and Chinese Science Citation Database) to identify literature published from its establishment to September 30, 2022. The following search strategy and keywords were used: (“left-behind children” OR “left-behind students” OR “left-behind teenagers” OR “stay-at-home children”) AND (“loneliness”). All research was limited to English- and Chinese language articles.

The steps of literature screening were as follows:

-

(i) Delete duplicate studies; (ii) read titles and abstracts for preliminary literature screening; (iii) read full text for secondary screening; (iv) obtain the final set of included studies.

Eligibility criteria

Two researchers (the first two authors: XY and LXL) independently selected and reviewed the articles if they met the following criteria: (i) the research participants were LBC; (ii) the articles were empirical investigations of Chinese left-behind children’s loneliness; (iii) NLBC were set up as a control group; (iv) the articles provided sufficient statistic information for the calculation or estimation of effect sizes (e.g., as sample size, mean value, standard deviations, t-value, F-value, or p-value).

Studies were excluded if any of the following criteria were met: (i) case reports, reviews, lectures, editorials, conference articles or correspondence letters; (ii) duplicate studies, with only the most recent studies with the most complete dataset being ultimately selected; (iii) no control group, or the norm was used as the standard control; (iv) the original data were incomplete, or the supplementary data were not available.

Statistical analysis

We conducted a meta-analysis using Revman and Stata software (Revman 5.4 version). We used the odd ratio (OR) to assess the difference in loneliness between LBC and NLBC. Because of the different score units used by the papers, we calculated the standardized mean difference (SMD) to assess the effect size. The confidence interval was set at 95%. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We also conducted a sub-group analysis based on different grades, guardians, and measurement tools The heterogeneity among the results was tested using the I2 statistic and was considered to be statistically significant at I2 greater than 50%. The fixed-effects model was used if there was no heterogeneity; otherwise, we used the random-effects model. A funnel plot was utilized to detect potential publication bias, If the scatter in the funnel plot is symmetrical, there is no publication bias. Finally, the forest map was drawn using GraphPad Prism 9.

Results

Data extraction

The following information was extracted from each eligible study: the first author, publication year, measurement tool, and total LBC and NLBC numbers. The data for each mean and standard deviation of the loneliness score of the LBC were also extracted according to education level, guardianship type, and measurement tool. A total of 300 potentially relevant articles were initially screened in the databases based on our literature searching strategy. 62 of which were subsequently removed due to duplication; 238 papers were selected for further screening. After screening based on titles, abstracts, and full texts, we included 23 studies in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the studies and methodological quality

A total of 23 articles (Fan et al., 2016, 2017, Xie et al., 2015, Fan et al., 2014, Fan & Wu, 2020, Zhao, 2013, Zhao et al., 2013, Fan et al., 2009, Fan, 2011, Zhang, 2011a, b, Liu et al., 2008, Hou & Xu, 2008, Zhang et al., 2022, Yang et al., 2016, Zhang et al., 2014, Ling et al., 2012, Yue & Lu, 2015, Wang et al., Shen , 2011, Yue et al., 2014, Li et al., 2020, Xiong et al., 2019) were included in this study, all of which were cross-sectional studies, with a maximum sample size of 1,606 and a minimum sample size of 124. The age and grade ranges of the sample were 4–16 years old and grades 3–9, respectively, and a total of 6,678 LBC were included. All studies screened subjects and participants. The characteristics of the 23 studies included in this review are shown in Table 1.

Methodological quality assessment for all included studies was performed using the quantity table modified by (Downs & Black, 1998) and (Ferro & Speechley, 2009). The scale originally had 15 items, “Do the staff, locations, and facilities of the study patients represent the treatment that the majority of the patients receive?” was deleted from the revised Quality Assessment Scale by Ferro and Speehley because it is not suitable for assessing LBC with loneliness. The revised assessment scale has 14 items on four aspects of methodological quality: the (i) report (e.g., “Are the assumptions / objectives of the study clearly described?”); (ii) external validity (e.g.,“Are participants asked to participate in a study representing the entire population? How are they being recruited?”); (iii) internal validity (e.g.,“Are the primary outcome measures used valid and reliable?”); (iv) efficacy (“Does the study provide sample size or efficacy calculations to detect differences in probability values by chance < 0.05?” ).Each entry is scored as 0 (no/uncertain) or 1 (yes). The total score ranges from 0 to 14, with a higher score reflecting better literature quality. The 23 studies were scored, and the results showed that 4 studies had an average quality index, while the remaining 9 studies all scored 10 points and above, with a good quality index, indicating that the quality of the included literature was good.

Loneliness measurement tools

The scales used in the included analysis were all loneliness scales. The most common loneliness measurement scales are the Children’s Loneliness Scale (CLS) and the UCLA Loneliness Scale. The CLS is a child loneliness scale compiled in 1984 by Asher. The scale contains 24 items, 16 of which are used to measure children’s loneliness, with 10 positive scoring questions and 6 reverse scoring questions. Additionally, eight questions about children’s preferences were inserted to detect whether children lie when filling out the questionnaire. The items are scored on a 5-point scale, with 1 indicating “never” and 5 indicating “always”. The higher the final score, the stronger the loneliness.

The UCLA scale is a one-dimensional loneliness scale compiled by Russell et al. 1987 (Liu, 1999) to measure loneliness as the difference between the desired and real levels of social interaction. There are 20 items in the full scale, rated on a 5-point scales, among which 9 items are scored in reverse order. The higher the score, the higher the degree of loneliness. In most experimental studies in China, loneliness scale compiled by foreign scholars (such as the UCLA loneliness scale) have been used as the evaluation standard of experiments, but this scale is more suitable for adolescents rather than children compared with the CLS. Therefore, most related studies on loneliness among LBC at home and abroad use the CLS scale.

Effect size and homogeneity tests

The obtained mean effect size of the 23 studies included in this meta-analysis for exploring the effectiveness of levels of loneliness was SMD = 0.22, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.15–0.28. The results indicated that the loneliness level of LBC was higher than that of NLBC (Z = 6.41, P < 0.001). The heterogeneity among the 23 studies was relatively large (I2 = 65%, P < 0.01). According to the result of the random effects model, we found that the reasons for the heterogeneity may be complicated, and we believe that further research is indispensable (Fig. 2).

Subgroup Analysis

For further analysis and to identify sources of heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analysis in terms of the grades, guardianship types, and measurement tools of the LBC. The results showed high heterogeneity in both the primary school group (I2 = 63%, P < 0.001) and the junior high school group (I2 = 72%, P < 0.001). The total effect size between the two groups (I2 = 0%, P = 0.93) indicated that there was no significant difference in the effect size between the primary and middle school groups; that is, there was no significant difference in the degree of loneliness between the two groups.

In terms of the guardianship types, the SMD scores for other relative guardianship were higher than those for single-parent guardianship (SMD = 0.24, 95% CI = 0.17, 0.31), and the total effect size (I2 = 78.5%, P = 0.03) between the two groups indicated significant differences; that is, there were differences between the LBC of single-parent guardianship and other relative guardianship. According to the analysis results, LBC under single-parent guardianship were less lonely than those under the guardianship of other relatives. Moreover, the total effect size between the two groups of measurement tools (I2 = 0%, P = 0.62) indicated that there was no significant difference in the effect size between the CLS and UCLA, meaning there was no difference in the degree of loneliness measured by different measurement tools (Table 2).

The results of the subgroup analysis showed that the degree of loneliness among LBC in both primary and middle school groups was high, which may mean that there were other regulatory variables in the assessment of loneliness between the two groups. Guardianship type subgroup analysis results showed that the loneliness of LBC under single-parent guardianship was lower than that of LBC under other relative guardianship. The study results are consistent with those of (Huang & Li, 2007) and others, who believed that parents play an irreplaceable role in childhood, even if only one parent is present, as they provide more dedicated care than other caregivers, offer more psychological comfort, and can better promote children’s mental health.

Publication bias

A funnel plot was applied to evaluate the publication bias of studies. Analysis of publication bias showed symmetric distribution (Fig. 3). Taken together, the calculated overall effect size seems to be rather robust and show a lack of publication bias.

Discussion

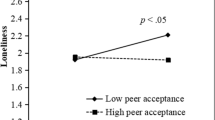

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that the loneliness level of LBC is higher than that of NLBC (Z = 6.41, P < 0.001), and the detection rate of loneliness among LBC was 22%. The government has repeatedly stressed the need to establish and improve the care service system and rescue and protection mechanism for LBC to ensure their mental health, indicating that the mental health of LBC has been of highly concern to the country and society (China, 2016). Our study showed that LBC had worse loneliness issues than NLBC, the results are similar to previous studies. According to previous studies, the level of loneliness of LBC is affected by many factors, such as peer relationships, school atmosphere, frequency of contact with parents, and age at separation from parents. The improvement of peer relationships will reduce LBC’s level of loneliness; the higher the peer acceptance of children and the number of close friends, the lower the level of loneliness (Uruk & Demir, 2003). In addition, a good school atmosphere is negatively related to the loneliness of LBC, with the support of teachers and students being protective factors against the emotional behavior problems of LBC. In addition, (Zhang & Feng, 2011) showed that the better the teacher–student relationship, the lower the loneliness level of LBC. High-frequency, high-quality interaction between parent and child can improve adolescent emotional adaptation; otherwise, it is not conducive to adolescent mental and emotional health, which can lead to the emergence of loneliness (Larranaga et al., 2016). The younger the LBC are separated from their parents, the more loneliness symptoms appear (Zhang et al., 2018); likewise, the longer the separation from their parents, the more negative emotions appear (Lu et al., 2015). Loneliness can have a range of detrimental effects. Evidence suggests that a chronic and painful state of loneliness may contribute to a constellation of psychosocial problems, including depression, low self-esteem, conduct problems, and suicide attempts (Chai et al., 2019). These findings also explain why the loneliness of LBC must be given high attention.

Previous studies found that LBC with other relative guardianship reported higher levels of loneliness than those with single-parent guardianship (Yue & Lu, 2015), whereas other studies found no difference in loneliness between these two groups (Su et al., 2013). Our results indicate that LBC under other relative guardianship reported higher levels of loneliness than those under single-parent guardianship, similar to the results of (Wu et al., 2019). The following factors may explain this phenomenon. First, Since one or both parents are absent, the interaction between LBC and their parents is not conducive to the formation of a secure attachment relationship, which will negatively affect the physical and mental development of LBC (Al-Yagon et al., 2016). Based on the empirical analysis of logit model, (Liu et al., 2020) divided LBC into different types and found that children left behind by two parents were more lonely than those left behind by one parent. Second, for single LBC, the guardian not only assume multiple social roles, such as raising children, household care, labor production, and supporting the elderly, but also worries about the safety of the partner, resulting in mental pressure, which leads to a lack of patience for childrearing, with the parenting being simple, rough, easy to anger, and more often abusive (Ye & Wang, 2006). All of the above conditions may adversely affect the psychology of LBC.

Comparing the loneliness scores between primary and junior high school LBC, we could not find any significant differences. This means that loneliness does not decrease with grade or age. Considerable evidence has confirmed that the psychological problems of left-behind children are long-term. Because childhood and adolescence are critical periods for psychological and physical development, disrupted parental attachment during these critical periods may result in long-term psychopathological consequences that do not dissipate over time (Xu et al., 2018).

In addition, according to I2 of the subgroup analysis, we found that the heterogeneity was reduced only by the type of care, so we can speculate that different types of care may be the source of heterogeneity, which may be due to different guardians leading to different LBC loneliness scores, ultimately leading to a higher heterogeneous combined effect size. Additionally, according to the results of the funnel plot, the research results were relatively stable, and there was no obvious publication bias.

In summary, many LBC have a high levels of loneliness. The results suggest that social authorities and public health organizations should be aware that children left behind have a high level of loneliness. There is an urgent need for more care services to assess and manage these children. If possible, a psychological guidance plan should be developed according to the level of loneliness problems of each child.

Limitations

There are some limitations that need to be considered in the current meta-analysis. First, language bias should not be ignored. All included studies were Chinese studies because there were no English-language studies on this issue. Second, although publication bias was not detected in most of our results, it could still exist because only published articles were included. Third, there was high heterogeneity in this meta-analysis. In addition, the impact of gender and other unclear potential covariates on the loneliness of LBC could not be estimated because these data were unavailable in the eligible articles. Despite its limitations, this study has important implications for future research and practice to promote the health of LBC. This study can help bring more attention to LBC from society and academia, so as to formulate relevant policies to solve LBC’s mental health problems, reduce their loneliness and other issues, and promote their positive development.

Conclusion

In summary, the findings of this meta-analysis suggest that (i) LBC have a high level of loneliness, which requires the attention of relevant departments; (ii) there is no significant difference between the loneliness of primary and junior middle school LBC; (iii) other relative guardianship is more likely to cause loneliness in LBC than single-parent guardianship. Future research should develop individualized teaching and corresponding intervention measures for LBC of different ages and guardianship types; and (iv) there are still some limitations to this study; thus, further and more extensive research is needed in this field.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Al-Yagon, M., Kopelman-Rubin, D., & Mikulincer, M. (2016). Four-model approach to adolescent-parent attachment relationships and adolescents’ loneliness, school belonging, and teacher appraisal. Personal Relationships,23, 141–158.

Antia, K., Boucsein, J., Deckert, A., Dambach, P., Račaitė, J., Šurkienė, G., Jaenisch, T., Horstick, O., & Winkler, V. (2020). Effects of international labour migration on the mental health and well-being of left-behind children: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4335.

Asher, S. R., Asher, S. R., & Paquette, J. A. (2003). Loneliness and peer relations in childhood. Current Directions in Psychological Science,12(3), 75–78.

Ben Simon, E., & Walker, M. P. (2018). Sleep loss causes social withdrawal and loneliness. Nature Communications, 9(1), 3146.

Chai, X. Y., Du, H. F., Li, X. Y., Su, S. B., and Lin, D. H. (2019). What really matters for loneliness among left-behind children in rural China: a meta-analytic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 10.

Cheng, P., Da, C., Cao, F., Li, P., Feng, D., & Jiang, C. (2010). A comparative study on psychological abuse and neglect and emotional and behavioral problems of left-behind children and non-left-behind children in rural areas. Journal of Clinical Psychology,18, 250–253.

China, S. C. O. (2016). Opinions of the state council on strengthening the care and protection of Rural left-behind children.

Cicchetti, D., Rogosch, F. A., Gunnar, M. R., & Toth, S. L. (2010). The differential impacts of early physical and sexual abuse and internalizing problems on daytime cortisol rhythm in school-aged children. Child Development, 81, 252–269.

Cosan D. (2014). An evaluation of loneliness. Annual international conference on cognitive - social, and behavioural sciences (icCSBs), May 14–17 2014 Mersin, Turkey. 103–110.

Ditommaso, E. S. (1997). Social and emotional loneliness: A re-examination of Weiss’ typology of loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences,22(3), 417–427.

Downs, S. H., & Black, N. (1998). The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of epidemiology and community health,52, 377–384.

Fan, X. H. (2011). On the comparison of emotional adaptation between left-at-home rural children of various types and normal children. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 71–77.

Fan, Z. Y., & Wu, Y. (2020). Relationship between parent-child relationship, loneliness and depression among the left-behind rural children: Gratitude as a mediator and a moderator. Psychological Development and Education, 36, 734–742.

Fan, X. H., Fang, X. Y., Liu, Q. X., & Liu, Y. (2009). A social adaptation comparison of migrant children, rear children, and ordinary children. Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Sciences), 33–40.

Fan, X. H., Fang, X. Y., Zhang, S. Y., Chen, F. J., & Huang, Y. S. (2014). Mediation of extroversion and self-esteem on relationship between family atmosphere and loneliness in rural parent-absent children. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 22, 680–683.

Fan, X. H., He, M., & Chen, F. J. (2016). Effect of Hope on the relationship between parental care and loneliness in left-behind children in Rural China. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24, 702–705.

Fan, X. H., Yu, S., Peng, J., & Fang, X. Y. (2017). The relationship between perceived life stress,loneliness and general well-being among the left-behind rural children: Psychological capital as a mediator and moderator. Journal of Psychological Science, 40, 388–394.

Ferro, M. A., & Speechley, K. N. (2009). Depressive symptoms among mothers of children with epilepsy: A review of prevalence, associated factors, and impact on children. Epilepsia, 50, 2344–2354.

Hou, Y., & Xu, Z. (2008). Loneliness and inferiority complex of rural left-behind children. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 564

Huang, Y. P., & Li, L. (2007). Mental health status of different types of left-behind children. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 669–671.

Ji, W., & Zhuo, R. (2017). Loneliness and mental health of rural left-behind children in Jilin Province. Chinese Rural Health Service Administration,37, 950–951.

Larranaga, E., Yubero, S., Ovejero, A., & Navarro, R. (2016). Loneliness, parent-child communication and cyberbullying victimization among spanish youths. Computers in Human Behavior,65, 1–8.

Lempinen, L., Junttila, N., & Sourander, A. (2018). Loneliness and friendships among eight-year-old children: Time-trends over a 24-year period. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry,59, 171–179.

Li, M. L., Ren, Y. J., & Sun, H. (2020). Social anxiety status of left-behind children in rural areas of Hunan province and its relationship with loneliness. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 51, 1016–1024.

Lin, H. (2003). Investigation of the present situation about Fujian guarded children education. Journal of Fujian Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 132–135.

Ling, H., Zhang, J. R., Zhong, N., Yi, Y., Zhou, L. J., Hong, W. Y., & Wen, J. (2012). The Relationships between the left-home-kids’ loneliness, friendship quality and social status. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20, 826–830.

Ling, H. Y., Chang, F., Yue, A., & Wang, H. (2017). The impact of parental migration on the mental health of rural left-behind children. J Peking University Education Review, 15, 161–174+192.

Liu, P. (1999). UCLA solitude scale (third edition). Chinese Journal of Mental Health,(Suppl), 282–228.

Liu, X., Hu, X. Y., & Shen, J. L. (2008). The influence of different sources of social support on the loneliness of rural left-behind children. Journal of Henan University (Social Sciences), 18–22.

Liu, L. J., Sun, X., Zhang, C. L., Wang, Y., & Guo, Q. (2010). A survey in rural China of parent-absence through migrant working: The impact on their children’s self-concept and loneliness. BMC Public Health,10, 32.

Liu, Y., Yang, X., Li, J., Kou, E., Tian, H., & Huang, H. (2018). Theory of mind development in School-Aged left-behind children in rural China. Frontiers In Psychology,9, 1819.

Liu, J. H., Wu, X., & Qin, C. R. (2020). Study on the influence of parent-child affinity on loneliness of children left behind in rural areas. Population and Development,26, 79–87.

Lu, X., She, L. Z., & Li, K. S. (2015). Research on emotional problems and parent-child attachment among left-behind children. Theory and Practice of Contemporary Education, 7, 141–144.

Maes, M., Vanhalst, J., Spithoven, A. W., Van den Noortgate, W., & Goossens, L. (2016). Loneliness and attitudes toward aloneness in adolescence: A person-centered approach. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(3), 547–567.

Mishra, S. K., Kodwani, A. D., & Jain, K. K. (2018). Linking loneliness to depression: A dynamic perspective. Benchmarking: An International Journal,25, 2089–2104.

Ouellette, D. M. (2004). The social network and attachment bases of loneliness. Virginia Commonwealth University.

Ren, Y. J., Yang, J., & Liu, L. Q. (2017). Social anxiety and internet addiction among rural left-behind children: The mediating effect of loneliness. Iranian Journal of Public Health,46, 1659–1668.

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1987). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol, 39(3), 472–80.

Su, S., Li, X., Lin, D., Xu, X., & Zhu, M. (2013). Psychological adjustment among left-behind children in rural China: The role of parental migration and parent-child communication. Child Care Health and Development, 39, 162–170.

Tang, D., Choi, W. I., Deng, L., Bian, Y., & Hu, H. (2019). Health status of children left behind in rural areas of Sichuan Province of China: A cross-sectional study. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 19, 4.

Uruk, A. C., & Demir, A. (2003). The role of peers and families in predicting the loneliness level of adolescents. The Journal of psychology,137, 179–193.

Wang, D., & Pan, L. (2020). The living condition of the left-behind children in difficult situations and the construction of supporting system. Journal of China Agricultural University(Social Sciences), 37, 106–113.

Wang, X. Y., Hu, X. Y., & Shen, J. L. (2011). Affection of left children’s friendship quality on loneliness and depression. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 19, 252–254.

Weiss, R. S. (1973). Loneliness: the experience of emotional and social isolation. MIT Press.

Wen, M., & Lin, D. (2012). Child development in rural China: Children left behind by their migrant parents and children of nonmigrant families. Child Development, 83, 120–136.

Wright, C. L., & Levitt, M. J. (2014). Parental absence, academic competence, and expectations in latino immigrant youth. Journal of Family Issues,35, 1754–1779.

Wu, W., Qu, G. B., Wang, L. L., Tang, X., & Sun, Y. H. (2019). Meta-analysis of the mental health status of left-behind children in China. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health,55, 260–270.

Xie, Q. L., Wan, R., & Zhang, R. (2015). Relationships between self-esteem, social support, coping style and loneliness among college rural freshmen with left-behind experience. Chinese Journal of School Health, 36, 236–238.

Xiong, Y. K., Wang, H., & Liu, X. (2019). Peer victimization, maternal control, and adjustment problems among left-behind adolescents from Father-Migrant/Mother caregiver families. Psychology Research and Behavior Management,12, 961–971.

Xu, W., Yan, N., Chen, G., Zhang, X., & Feng, T. (2018). Parent-child separation: the relationship between separation and psychological adjustment among chinese rural children. Quality of Life Research, 27, 913–921.

Yang, Q., Yi, L. L., & Song, W. (2016). Relation of loneliness to family cohesion and school belonging in left-behind children. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 30, 197–201.

Ye, J. Z., & Wang, Y. H. (2006). The guardianship status and characteristics of left-behind children. Population Journal, 55–59.

Yue, L., Sun, F. Y., & Liu, Y. (2014). Investigation and analysis of the loneliness of the left-behind children in the remote areas of Hunan Province. Maternal and Child Health Care of China, 29, 3320–3323.

Yue, S. H., & Lu, X. Y. (2015). Comparison of social support and loneliness among left-behind children in eastern and western China. Chinese Journal of School Health, 36, 1662–1664.

Zhang, J. L. (2010). A probe into the problems of rural left-behind children from the perspective of public policy. Special Zone Economic, 6, 153–154.

Zhang, L. Y. (2011a). On the relationship between the social support for Left-at-home rural children and their loneliness. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 80–84.

Zhang, L. Y. (2011b). A study of social relationships and loneliness of the rural left-behind children. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 19, 123–125.

Zhang, H. L. (2014). Does parental absence reduce cognitive achievements? Evidence from rural China. Journal of Development Economics, 111, 181–195.

Zhang, J. F., & Feng, D. G. (2011). Study on the teacher-student relationship and loneliness of left-behind children in rural areas. (pp. 107–109). News Universe.

Zhang, L., Wang, Q. Y., & Zhao, J. X. (2014). Caregiver’s support, beliefs about adversity and loneliness in rural left-behind children. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 22, 350–353.

Zhang, H., Yang, K. (2012). Research on the Relationship between Anxiety, loneliness and overall well-being of college students [C]// Sichuan Psychological Society. Psychology and Society -- Proceedings of 2012 Academic Annual Meeting of Sichuan Psychological Society (vol. 2012, p. 5). Northeast Normal University Press,

Zhang, X., Deng, M., Ran, G., Tang, Q., Xu, W., Ma, Y., & Chen, X. (2018). Brain correlates of adult attachment style: A voxel-based morphometry study. Brain Research,1699, 34–43.

Zhang, Y. H., Zhang, T., & Zhao, J. X. (2022). The relationship between perceived discrimination and left-behind adolescent’s loneliness: The moderating roles of separation age and separation duration. Psychological Development and Education, 38, 90–99.

Zhao, J. X. (2013). Parental monitoring and left-behind-children′s antisocial behavior and loneliness. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 21, 500–504.

Zhao, L., Ling, H., Zhou, L. J., Wen, J., & Hong, W. Y. (2013). Research on left-behind children’s loneliness and friendship quality in different guardian condition. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 21, 306–308.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent to publish

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All authors agree with the release of this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yan Xiong and Xiaolin Li are co-first authors.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 27.3 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, Y., Li, X., Li, H. et al. A meta-analysis of loneliness among left-behind children in China. Curr Psychol 43, 10660–10668 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04882-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04882-w