Abstract

Personal values and socioeconomic status (SES) both influence adolescents’ subjective well-being, yet there is still a need to explore whether differences in values and SES have different impacts on one’s subjective well-being (SWB). This study examined the moderation effect of SES in the relationship between two values (self-improvement and collective responsibility) and SBW. A sample comprising 600 Chinese college students (23.40% boys, mean age = 21.21, SD = 1.56) were measured twice over the course of one year using the Chinese Adolescent Values Questionnaire and the Subjective Well-Being Questionnaire. Results showed that self-improvement value may promote SWB of students with a low SES, but this result was not seen in the students with a high SES. Meanwhile, collective responsibility value may promote SWB in students with a low SES, while it may reduce SWB in students with a high SES. Our findings suggested that self-improvement and collective responsibility values can help low SES students access resources and support, helping them overcome unfavorable situations. However, a different picture was shown for students with a high SES. In contrast to the low-SES students, these two values seemed to restrict the growth of students with a high SES, hampering their pursuit of their own goals and interests, which may ultimately diminish their SWB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Subjective well-being (SWB) is one’s overall evaluation of their quality of life according to their own standards, and is an important index of one’s quality of life and mental health (deVries et al., 2016). Adolescence is an important period of individual psychological maturity and development of well-being. Revealing the factors and developmental mechanism affecting adolescents’ SWB is of great significance to promote positive and healthy development of adolescent physiology and psychology.

Among the factors affecting SWB, values are of particular importance. Sortheix and Schwartz (2017) suggested that relations of values to SWB depend upon the motivational underpinnings expressed by values. They differentiated two cohorts of motivational underpinnings. One cohort was growth orientation and person focus motivational underpinnings, while the other cohort was self-protective orientation and social focus. The study suggested that values expressing growth orientation (such as benevolence) and person focus (achievement) both promoted SWB. These values, satisfying intrinsic needs for relatedness and autonomy, do so because they motivate self-actualizing or free expression of one’s own ideas or abilities. In contrast, the values, expressing self-protective orientation (power) and the social focus (conservation) motivational underpinnings, both undermined SWB. These values, directed toward extrinsic needs for approval and status, do so because they motivate the subordination of the self to socially-imposed expectations or asserting control and dominance to overcome anxiety.

In Schwartz’s values research, values are classified on the basis of deep human motivation. From this division of values, we can see that the system of human values is roughly divided into 2 categories. The first category is concerned with individual human values, including personal emotions, wealth, thoughts and behaviors. The second category is values that focus on others, relationships, and groups, including concern for others, social rules, and group well-being (Schwartz, 1992). That is to say, self-and group-oriented values may represent two fundamental domains of beliefs. Self-oriented values are mainly characterized by independence and uniqueness that motivate individuals to actively make their own choices and decisions (Oyserman, 2017). In contrast, group-oriented values tap into a sense of social affiliation in the group and emphasize the attainment of group benefits and interpersonal relationship harmony (Chen, 2015).

Based on this, this study selected representative Chinese self-group orientated values for research. Although there are differences between Eastern and Western values, the classification of the two types of values has a long history (Hofstede, 1980). And, for nearly 40 years, Chinese values have been influenced by Western values (Chen, 2015; Chen et al., 2018; Shek et al., 2022). All these results showed the collision of Chinese and Western values. We certainly do not ignore the differences between Chinese and Western values. These differences will be explained and explored in our study. And we believe that the differences in values will allow us to better understand the characteristics and trends in the formation and development of values among contemporary Chinese adolescents.

In addition to values, a large number of studies into the influencing factors of SWB have found that individual SWB is largely affected by social economic status (SES) indicators such as income and education (Anderson et al., 2012). Socioeconomic status (SES) refers to the objective social position of an individual defined by the resources he or she possesses, and is often assessed by his or her professional prestige, education level and income level (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002). Since college students do not yet have stable economic resources, their SES is usually assessed by their family SES instead, i.e., by their parents’ occupation, parents’ education level and family incomes (Ding et al., 2020).

However, the role that SES plays on SWB is as yet ambiguous, suggesting that not all individuals suffer damage to their SWB when experiencing socioeconomic adversity (Leung & Shek, 2016; Li et al., 2016; Li et al., 2021)). That is to say, individuals may construct tendencies to diminish negative impacts of their poor resources or lower rank on their SWB. Values are an optional system which can help adolescents from a low SES enhance their SWB. Further, the effect of values on individual well-being is subject to moderation by SES. Low SES groups are more likely to enhance their well-being by adhering to certain values in the face of adversity (Leung & Shek, 2016; Li et al., 2021). This is because adherence to values can make individuals feel that life is more meaningful and more capable of changing adversity.

Within Confucian values, self-improvement and collective responsibility are both rather important. They are emphasized by both the state and family (Liu et al., 2018; Chen, 2015). As long as one sticks to these two values, not only can individuals better develop a more moral personality, but they are also better able to serve their country as well. Therefore, compared to individuals of high SES, individuals from a low SES tend to agree more with these two Confucian values (Chen, 2015; Li et al., 2018). The mechanism of values on low SES individuals was consistent with opinions of value-environment congruence and SWB (Schwartz & Sortheix, 2018). When individuals identify with similar values in their environment, these values, as a normative force, can promote one’s SWB. People following such values are more likely to get social support from others within that same environment. At the same time, when sharing similar values with other individuals in the environment, people have less internal value conflict, which may also enhance SWB (Schwartz & Sortheix, 2018).

There still remains a question that needs to be explored: are there harmful impacts on SWB when people from a high SES agree more strongly with self-improvement and collective responsibility values? Kraus et al. (2012) argued that people of high SES had abundant resources and an elevated occupational rank that enhanced their personal freedoms, leading to people of high SES developing individualistic tendencies that focused on their own internal goals, motivations, and emotions. This suggested a contradictory consequence of collective responsibility value on SWB. If people of high SES identified more strongly with collective responsibility value, they could develop a more communal self-concept, or they could feel more compassion towards others and behave more prosocially (Kraus et al., 2012), despite it going against their individualistic tendencies.

Indirect evidence was also provided by the study of Chen et al. (2018). For Canadian children, social sensitivity (valuing the evaluation and feedback of others and avoiding social exclusion) may have a negative impact on children’s development, for example, social sensitivity was positively associated with disliking by peers, loneliness, and depression, and negatively associated with social competence, academic achievement (Chen et al., 2018). However, as for rural Chinese children, social sensitivity (receiving approval and support from others and establish positive social relationships), were conducive to school achievement and socioemotional adjustment (Chen et al., 2018). These results also reflected the moderating effect of SES on values on SWB, that is to say, more identifying responsibility value maybring about more internal conflicts (tension between their own needs and others’ opinions), which might diminish their SWB.

As for the relation between self-improvement value and SWB, this differed to the relation between collective responsibility value and SWB. The self-improvement value emphasized individual goals and achievement, which was consistent to the individualistic tendencies of people of high SES. However, the value of self-improvement in the Confucian values also emphasizes continuous reflection on one’s own shortcomings and desires, so as to improve one’s morality, which to some extent restricts personal freedoms. Consequently, more identification with self-improvement value both enhanced SWB of individuals with high SES (because they can achieve their goals and attain accomplishments) and weakens their SWB (suppressing desires; demanding themselves according to social morality). And positive and negative influences offset each other, making no certain hypotheses about the impacts of identification with self-improvement value on SWB.

To conclude, the present study attempted to evaluate the moderating effect of SES on the relation between the values of self-improvement and collective responsibility and SWB. According to the theory of values, values are the deep motivational system of human beings. The identification of values can satisfy the needs of individuals and influence their behavior. These can affect individuals’ well-being. However, to make up for the deficiency of cross-sectional studies and to better explore the causal relationships, we adopted a longitudinal study approach in our research design, i.e., we used values measured in the first year (T1) as the independent variable and SWB measured in the second year (T2) as the dependent variable, and used regression analysis to examine the impacts of values on SWB. To make the statistical results more robust, we also controlled for the effect of T1SWB on T2SWB, i.e., T1SWB was set as a covariate to control for. Our hypotheses were as follows:

-

Hypothesis 1. T1Self-improvement and T1collective responsibility values can positively predict T2SWB.

-

Hypothesis 2. SES can moderate the relationship between T1self-improvement value and T2SWB; specifically, the more students of low SES agree with the value of T1self-improvement, the more numerous their levels of T2SWB, but there would be no similar significant effect on students with high SES.

-

Hypothesis 3. SES moderates the relationship between T1collective responsibility value and T2SWB, specifically, the more students of low SES agreed with the value of T1collective responsibility, the more numerous their levels of T2SWB; on the contrary, the more students of high SES agreed with T1collective responsibility value, the fewer levels they had of their T2SWB.

Participants and methods

Participants and procedure

Participants were recruited from two colleges in Shanghai, China. In the first survey, 683 students (Mage = 20.21, SDage = 1.56; 26.4% boys) were measured shortly after their enrollment (Time 1; T1). One year later, 600 students (23.4% boys) were measured once again (Time 2; T2). There were 83 students who had dropped out from completing the second survey. Using SES, collective responsibility value, self-improvement value, and SWB as the dependent variables while retained and missing participants as the independent variable, MANOVA analyses revealed no significant differences between those who dropped out of the study and those who continued to take part at T2 (Wilks’ lambda = .98, F(4, 663) = 2.01, p = .11, η2 = .01). Informed consent was obtained from participants, then the paper-pencil questionnaire was completed during class under the supervision of a researcher and a teacher.

Measures

Values (CR/S-I)

Values were measured using the Chinese Youth Values Questionnaire (Wang et al., 2018), which is a self-report measure with a total of 46 items, each one scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very like me) to 5 (not like me at all). Higher scores indicate more identification on a certain value. The questionnaire has eight dimensions: social equality, collective responsibility, rule abiding, family well-being, friendship, self-improvement, fashion, and personal happiness. We selected two dimensions for use in this study: collective responsibility value (CR) (“he/she believes that everyone should think for the group, and that collective interests are very important”) and self-improvement value (S-I) (“he/she believes that people should always think about how to improve their own ability”). The Cronbach’s α coefficient of T1CR was 0.86. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of T1S-I was 0.84. The test-retest reliability r of (T1-T2)CR was 0.62. The test-retest reliability r of (T1-T2)S-I was 0.61. Research has shown that the questionnaire has good reliability and validity, and can be used to measure the values of adolescents (Li et al., 2018).

Subjective Well-Being (SWB)

The Chinese version of the Subjective Well-Being Scale was used to measure individuals’ SWB in comparison to that of others (Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999; Wang et al., 2021). There are four items in the scale, each of which is scored on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very unhappy) to 7 (very happy), and one of the items using reverse scoring. A sample of the items is: “Generally speaking, I think I am a happy person”. A higher total score indicates a higher level of SWB. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of T1 and T2 were 0.80 and 0.80, respectively. The test-retest reliability r of (T1-T2) SWB was 0.59.

SES

Generally, household income, parents’ education levels, and parental employment status are used as indicators of socio-economic status (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002). As such, parents’ occupation status, parents’ education levels, and family monthly income of participants were collected for this study. Parents’ occupation statuses were coded from 1 (unemployed or agricultural labor worker) to 5 (government officer or enterprise manager), with a total of five levels. Parents’ education levels were coded from 1 (primary school) to 5 (undergraduate), with a total of five levels. Family monthly income was coded from 1 (below 2000 yuan RMB) to 7 (above 20,000 yuan RMB), with a total of seven levels. The scores of the father and mother in the above three aspects were added together and averaged to obtain the family SES indicator.

Control and test of common method bias

All data were collected from the same source, which could have led to common method bias. The Harman single factor test was conducted to test for common method bias. Furthermore, an exploratory factor analysis of 27 variables (e.g., gender, age, index of SES, items of T1CR and T1S-I, items of T1/T2SWB) was conducted to test the hypothesis that a single factor could account for less than 40% of the variance in the data. Results revealed that the interpretation rate of the first common factor was 22.27%, which was less than 40%. This result indicated that there was no serious bias in the data.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 1. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relations between the main study variables. Results showed that the CR and S-I were positively correlated with T1/T2SWB, but negatively correlated with SES. In addition, T1SWB was positively correlated with SES.

Moderating analyses of S-I on SWB

First, all variables except gender were standardized. We then conducted moderating analyses using PROCESS 3.0 Model 1, taking T1S-I as the independent variable, T2SWB as the dependent variable, SES as the moderated variable, and gender, age, and T1SWB as the control variables. The results showed that there was a significant main effect of S-I (β = .11, p < .01) on SWB. Also, SES did moderate the relation between S-I and SWB (β = −.11, p < .01; see Table 2).

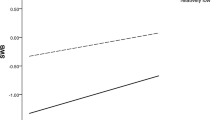

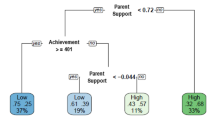

Then, a simple slope test was conducted to explore the association between S-I and SWB for low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of SES (see Fig. 1). The results revealed that, for the students with a low level of SES, there was a significant positive relationship between S-I and SWB (β = .22, p < .001, 95% CI [.12, .33]), but this relationship was not significant for the students with a high level of SES (β = .003, p = .94, 95% CI [−.09, .10]).

Moderating analyses of CR on SWB

We conducted similar moderating analyses, taking T1CR as the independent variable, T2SWB as the dependent variable, SES as the moderated variable, and gender, age, and T1SWB as the control variables. The results showed that there was a significant main effect of CR (β = .07, p = .04) on SWB. Also, SES did moderate the relation between CR and SWB (β = −.16, p < .01; see Table 3).

Then, a simple slope test was conducted to explore the association between CR and SWB for low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of SES (see Fig. 2). The results revealed that, for the students with a low level of SES, there was a significant positive relationship between CR and SWB (β = .28, p < .001, 95% CI [.15, .38]); however, for the students with a high level of SES, there was a significant negative relationship between CR and SWB (β = −.11, p = .04, 95% CI [−.22, −.01]).

Discussion

The important role and impact of values on adolescents’ SWB has already been acknowledged in the literature, yet little is known about the various influences of values on SWB in different SES contexts in contemporary Chinese adolescents, particularly in the context of social change. The current study extended the literature by exploring the positive and negative impact of college students’ values on SWB for Chinese adolescents in low or high SES contexts.

There is an argument made that self- and group-orientations coexists in contemporary Chinese adolescents (e.g., Chen, 2015; Liu et al., 2018) and, more specifically, that self-improvement and collective responsibility values are traditionally endorsed by Confucianism and continue to guide how Chinese adolescents evaluate social behaviors of both themselves and others (Yang et al., 2010). Self-improvement value emphasizes the construction of one’s own moral personality and leads to a continuous urge to self-transcend, which can lead one to earn further achievements and build one’s self-esteem. Both of these outcomes can be seen to promote SWB.

Collective responsibility value emphasized to care about well-being of others, abide by the collective rules and contribute to the group, which may brought sense of group belonging, meaning of life. All of these may also promote SWB. However, the mechanism of promotion appears to mainly help students with a low SES. Values guide culture-specific repertoires of behavior (Markus & Kitayama, 2010). Students of low SES face more diminished resources, more uncertainty, and more unpredictability. Holding self-improvement and collective responsibility values, however, can help them obtain resources and support so as to resist or overcome unfavorable situations. For high SES students, however, the findings showed a rather different picture. For them, holding self-improvement and collective responsibility values was to some extent a restriction. Students of a high level of SES already had relatively abundant material resources and were more free to pursue their own goals and interests. In this case, the aforementioned feeling of restriction hampered them in pursuing their own goals and interests, which can lead to diminishing SWB.

Sortheix and Lönnqvist (2014) assumed that values’ association to SWB depended on how well values function to help individuals cope with their environment. They proposed that in a country with a low level of human development (according to indices of affluence, health, and education) self-direction and achievement values related positively to SWB, which was consistent with our findings. Although China has carried out reforms and development for more than 40 years, there have been still huge differences in regional economic development. The economic development of the central and western regions has lagged far behind that of the eastern coastal areas. Even in the same province or city, there are huge differences in the level of education of different groups of parents, and in the wealth level of families. Most of the adolescents in economically undeveloped areas studied in the city and chose to work in the city. Therefore, reading, working, getting married and buying a house are all great challenges for them, which requires them to work hard all the time.

However, Sortheix and Lönnqvist (2014) also proposed that in a country with a high level of human development, social-focused values (e.g., universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity) related positively to SWB, which was inconsistent with our research results. As a freshman in this study, the social values such as collective responsibility value that individuals once identified with in high school began to have a negative impact on their SWB in college. Because after entering university, students with a high level of SES are able to make their own choices regarding pursuing their own hobbies, such as music, sports, games, tourism, etc. However, collective activities in college, such as class meetings, may always conflict with their personal schedule. According to the mechanisms tested in this study and supporting previous findings, person-environment value congruence influenced SWB (Sagiv & Schwartz, 2000). In high school, individuals identified collective responsibility value as being consistent with the environment, because students had similar growth backgrounds, their goals were all for college entrance examinations, and the collective responsibility value was also recognized by teachers. However, great changes take place in the college. The growth backgrounds of student peers are suddenly very different, and everyone’s interests and ambitions also become more distinct. Furthermore, students from a high level of SES have resources and tendencies to develop their own undeveloped interests and goals. Therefore, when they enter the university, they may more identify with values such as stimulation, hedonism, power, achievement, etc. These values may conflict with the collective responsibility value, at least in the short term. However, this internal conflict of values will reduce SWB.

Limitations and implications

Various limitations of this study should be noted. First, the current sample was recruited from only two schools, thus generalization of these findings may be limited. Second, given the self-report nature of the study, the causal role of these factors could.

not be inferred, and the findings should be interpreted with caution.

Despite these limitations, this research has important implications. First, the current findings may inform future research designed to uncover the underlying mechanisms behind values’ effects on SWB, especially the positive and negative roles of values on the SWB of individuals from different SES levels. Second, more concern should be paid to the education regarding the values in order to be able to be more significantly selective and specific as one guides adolescents through a healthy development.

References

Anderson, C., Kraus, M. W., Galinsky, A. D., & Keltner, D. (2012). The local-ladder effect: Social status and subjective well-being. Psychological Science, 23(7), 764–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611434537

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 371–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233

Chen, X. (2015). Exploring the implications of social change for human development: Perspectives, issues and future directions. International Journal of Psychology, 50, 56–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12128

Chen, X., Fu, R., Liu, J., Wang, L., Zarbatany, L., & Ellis, W. (2018). Social sensitivity and social, school, and psychological adjustment among children across contexts. Developmental Psychology, 54(6), 1124–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000496

deVries, M., Emons, W. H., Plantinga, A., Pietersma, S., van den Hout, W. B., Stiggelbout, A. M., & van den Akker-van Marle, M. E. (2016). Comprehensively measuring health-related subjective well-being: Dimensionality analysis for improved out come assessment in health economics. Value in Health, 19(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval

Ding, F., Yang, Y., Wang, Y., Jia, Y., & Cheng, G. (2020). Family socioeconomic status and college freshmen’s attitudes towards short-term mating: An analysis based on latent growth modeling. Psychological Development and Education, 39(5), 663–672. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2023.05.07

Hofstede, G. (1980). Cultures consequences: International differences in workrelated values. Sage.

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., Mendoza-Denton, R., Rheinschmidt, M. L., & Keltner, D. (2012). Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: How the rich are different from the poor. Psychological Review, 119(3), 546–572. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028756

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2016). The influence of parental beliefs on the development of Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage. Journal of Family Issues, 37(4), 543–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x13518776

Li, B., Li, A., Wang, X., & Hou, Y. (2016). The money buffer effect in China: A higher income cannot make you much happier but might allow you to worry less. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 234. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00234

Li, D., Zhou, T., Liu, J., Dai, Y., Chen, M., & Chen, X. (2018). Values of adolescent across regions in China: Relations with social, school, and psychological adjustment. Journal of Psychological Science, 41(6), 1292–1301. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20180602

Li, Q., Zhang, W., & Zhao, J. (2021). The longitudinal associations among grandparent–grandchild cohesion, cultural beliefs about adversity, and depression in Chinese rural left-behind children. Journal of Health Psychology, 26(1), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318803708

Liu, X., Fu, R., Li, D., Liu, J., & Chen, X. (2018). Self- and group-orientations and adjustment in urban and rural Chinese children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49, 1440–1456. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022118795294

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46(2), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1006824100041

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (2010). Cultures and selves: A cycle of mutual constitution. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 420–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610375557

Oyserman, D. (2017). Culture three ways: Culture and subcultures within countries. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 435–463. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033617

Sagiv, L., & Schwartz, S. H. (2000). Value priorities and subjective well-being: Direct relations and congruity effects. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30, 177–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(200003/04)30:2<177::AID-EJSP982>3.0.CO;2-Z

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60281-6

Schwartz, S. H., & Sortheix, F. M. (2018). Values and subjective well-being. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being. DEF Publishers.

Shek, D. T., Dou, D., Zhu, X., Li, X., & Tan, L. (2022). Materialism, egocentrism and delinquent behavior in Chinese adolescents in mainland China: A short-term longitudinal study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4912. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084912

Sortheix, F. M., & Lönnqvist, J. E. (2014). Personal value priorities and life satisfaction in Europe: The moderating role of socioeconomic development. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(2), 282–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113504621

Sortheix, F. M., & Schwartz, S. H. (2017). Values that underlie and undermine well-being: Variability across countries. European Journal of Personality, 31(2), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2096

Wang, X., Li, D., Chen, X., Liu, J., Dai, Y., Guo, H., & Xu, T. (2018). Adolescent values and their relations with adjustment in the changing Chinese context. Journal of Psychological Science, 41(6), 1282–1291. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20180601

Wang, F., Sun, J., Li, Z., & Qin, Q. (2021). Relationship between self-reflection and subjective well-being among Chinese adults:The mediating role of problem solving tendency. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 29(1), 104–108. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.01.021

Yang, K. S., Liu, Y. L., Chang, S. H., & Wang, L. (2010). Constructing a theoretical framework for the ontogenetic development of the Chinese bicultural self: A preliminary statement. Chinese Journal of Psychology, 52, 113–132. https://doi.org/10.6129/CJP.2010.5202.01

Funding

This study was funded by the Program of Shanghai Educational Science Research (C2022403, C2022367).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LL made substantial contribution to the analysis and interpretation of the data, drafted the manuscript, provided the final approval for the manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. XW made substantial contributions to the conception and the design of the study, drafted the manuscript, provided final approval for the manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lan, L., Wang, X. Socio-economic status moderates the relationship between values and subjective well-being among Chinese college students. Curr Psychol 43, 6253–6260 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04818-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04818-4