Abstract

Judging truthfulness and detecting deception are critical in the criminal justice system as well as in many other applied contexts (e.g., clinical and business organizations). The ability to discriminate a truth-teller from a liar might be associated with the content of deception (e.g., emotional or high-stakes lies) or with the deceiver's characteristics, such as his/her level of confidence shown in lying. The two present studies aimed to manipulate the level of the sender’s confidence and to investigate its effect in deception vs. truthfulness judgments of written narratives varying in emotional content. A pilot sample (N = 124) assessed the stimuli validity of sixteen written narratives (Study 1): 8 deceptive vs. truthful narratives x four types of content (i.e., emotional/bereavement vs. emotional/car accident vs. emotional/quarrel vs neutral/holiday) with low confidence in the recall and 8 deceptive vs. truthful narratives x four types of content (i.e., emotional/bereavement vs. emotional/car accident vs. emotional/quarrel vs neutral/holiday) high in the confidence recall. An experimental sample (N = 428) was administered the two sequences of eight written narratives and for each narrative, veracity judgment, detection accuracy, and judgment confidence were assessed (Study 2). We found that the sender’s confidence, the veracity, and the content of the narratives affected receivers’ veracity judgments and detection accuracy. High confidence made receivers prone to judge bereavements and holiday narratives as truthful and quarrels narratives as deceptive. In addition, high confidence made judgments more accurate for truthful narratives on holidays compared with others, and for deceptive narratives on car accidents and quarrels than for other narratives. The present results are discussed in light of their practical implications for the legal field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Detecting if someone is deceiving and judging their credibility represent a relevant human faculty of great interest in countless fields, such as personnel selection (Donovan et al., 2003; Melchers et al., 2020), police interviewing (Caso et al., 2019), eye-witness memories (Vernham et al., 2020), daily social interactions (Gingo et al., 2020; Trifiletti et al., 2020; Verigin et al., 2019), information behavior and fake news (Luo et al., 2022; Zimmerman et al., 2020). Deception scholars agree that people’s capacity to discriminate a lie from truth is quite modest and ‘only slightly better than flipping a coin’ (Hauch et al., 2016, p. 284). Through a meta-analysis of 206 studies, Bond and DePaulo (2006) estimate an average accuracy rate of 54% across judgments. Some researchers have traced the mediocre lie detection ability to the lack of objective and unequivocal cues of lying (i.e., the lack of a ‘Pinocchio’s nose’), and to the biased and stereotyped judgments revolving around deceptive cues (Hartwig & Bond, 2011; Luke, 2019; Vrij, 2008). Although deception detection accuracy is reliably mediocre, there is considerable variation in response bias (i.e., the tendency to judge messages as truthful or deceptive; Bond & DePaulo, 2008). Here, we are interested in examining potential situational influences on response bias, namely the confidence with which a liar or truth-teller conveys their message and the message’s content.

Truthfulness judgements

Among the biases related to deception, the truth-bias is widely acknowledged as a robust phenomenon (Bond & DePaulo, 2006; Levine et al., 1999; McCornack & Parks, 1986; Park & Levine, 2017; Zuckerman et al., 1981): When interacting with others, people are inclined to believe others are basically honest. The Truth-Default Theory (TDT; Levine, 2014) posits that people are biased to passively presuppose or to actively trust that sender’s message is truthful, regardless of real truthfulness (Levine, 2014). The term truth-default refers to a passive assumption of honesty due to 1) an inability to account for the possibility of being deceived or 2) a fallback condition after failing to catch sufficient deception cues (Levine, 2014). In other words, the truth-default corresponds to an automatic and not conscious attitude of individuals to perceive others’ messages as honest regardless of the actual veracity of the message. By contrast, the term truth-bias specifically refers to the proportion of the sender’s messages judged as honest in some defined settings and occurs because of an active process of making inferences of honesty or deception about the message. The truth-bias assessed in an experimental setting generally corresponds to a prompted and active judgment on truthfulness (and not a cognitive default), and, in this vein, it is mostly influenced by the research setting and methodologies. In most lie detection experiments, the number of truthful and deceptive messages to be detected is equal (truth-lie base-rate), and this unavoidably influences the detection accuracy (the Park–Levine Probability Model; Park & Levine, 2001). For this reason, truth-default and truth-bias are similar and related constructs but not reciprocal. TDT argues that out of the laboratory, without an explicit request for the sample to detect both truth and deception, the truth-bias occurrences would be much higher. Strictly related to truth-default and truth-bias is the veracity effect (Levine et al., 1999): Individuals’ tendency to be significantly more accurate at judging truths than lie. Noteworthy, as pointed out in several articles, this tendency could be an artifact due to methodological and experimental issues (e.g., truth-lie base-rate), therefore it is more appropriate to state that studies have shown that when truth-lie base rate equates individuals' response bias, judgments’ accuracy increases.

Several explanations for the truth bias have been provided, such as heuristic processes (e.g., availability, anchoring, or falsifiability), social interaction rules, or self-presentational worry from deception detectors (Street & Masip, 2015; Vrij, 2008). Recently, Brashier and Marsh (2020) argued that data across different truth theories revealed the constructive nature of truth judgments. The authors schematized that truthfulness judgments are the product of three types of inference: 1) base rate, 2) feelings, and 3) consistency with knowledge stored in memory. First, following the Bayesian models of cognition, when people are asked to judge incoming information, they do not stay in an initial state of complete ignorance, but instead they move from a condition of a priori probability (Tenenbaum et al., 2006). Second, following the feeling-as-information theory (Schwarz et al., 2011), people use their affective state (feelings, emotions, mood) as a source of information to map the intervening situation and to interpret it. Feelings would act as a ‘tunnel’, leading individuals to focus on salient and useful information and to adapt strategies to contextual demands: Decision making, choices, problem-solving, and judgments. In this vein, people interpret their own subjective experiences as evidence of truth: Incoming messages experienced as simple and easy are more likely to be judged as true, than those felt as unfamiliar or difficult to perceive (Brashier & Marsh, 2020). Third, following the referential theory of the repetition-induced truth effect (Unkelbach & Rom, 2017), people make inferences from the pre-existing information stored in their memory. Starting from the robust evidence (but see also a study failing to replicate the repetition-induced truth effect: Henderson et al., 2021) that people are more likely to judge repeated statements as true compared to new statements (the so-called illusory truth effect, for a review see Dechêne et al., 2010), Unkelbach and Rom (2017) concluded that truth judgments are based on the amount and consistency of the match between the new incoming statement and the corresponding reference stored in memory. If this match takes place, prior presentation anchors these corresponding references into a coherent network.

Truth judgment, emotional content, and sender confidence

A substantial body of empirical evidence demonstrates that the ability to successfully catch lies depends more on the features and behaviors of the deceiver than on those of the detector (Bond & De Paulo, 2008; Lanciano et al., under review; Verigin et al., 2019). The liar's credibility better explains the variability in lie detection accuracy and judgment than any individual differences associated with the lie-catcher (George et al., 2014; Levine et al., 2011). Deception detection and credibility judgment feed on great empirical contribution from forensic witness literature and, although evaluation of witness credibility and witness accuracy are two questions that must be kept separated in the legal context (e.g., memories of trustworthy people are not necessarily accurate memories), they are often—and misleadingly—related in real life (Curci et al., 2020; Kaufmann et al., 2003; Porter et al., 2007).

What factors make senders being judged as most honest and their messages as truthful? In other words, moving from the well-established truth-bias, which variables do increase this biased judgment? The present study seeks to answer these questions, focusing 1) on the emotional content of the sender’s message and 2) on the level of confidence exhibited in the message. Across two studies, both factors have been experimentally manipulated.

Concerning the role of emotional content in detecting truthful or deceptive messages, according to Kaufmann and colleagues (2003), emotions displayed during testimony can be a strong determinant of the credibility judgment of a rape victim as well as of the estimated probability of guilt and beliefs about one’s own verdict in the case. In their study, participants were asked to view and judge video-recorded testimonies of a victim (an actress) of a rape in a congruent or incongruent version: In the congruent condition, she exhibited plausible emotions that one would expect to feel in a rape situation, whereas in the incongruent condition she displayed emotions jarring with the rape context, such as positive and pleasant feelings. They found that emotion—and not the content itself—was the most crucial determinant of credibility judgment. In this vein, Peace and Sinclair (2012) suggested the idea of a sort of emotional truth bias, according to which the participants would be distracted by the emotional content of the stimuli and this would prevent them from paying proper attention to any deception cues. The authors assessed the role of emotional content and psychopathy traits in judging the veracity of 12 written narratives (i.e., truthful/deceptive) across three emotional events (i.e., positive, negative, and neutral). They concluded that participants were more accurate in detecting truthful narratives than deceptive ones, and that detection accuracy was worse for emotional events than for neutral events. The use of detection cues varies as a function of the emotional narrative conditions. Similarly, investigated credibility judgments regarding real-life sexual assault allegations by asking people to discriminate between truthful vs. deceptive allegations. They found that overall accuracy was below chance with an evident truth bias. All the above-cited findings tangentially support the emotional victim effect (EVE): When disclosing their own victimization experience, victims who express highly intense negative emotions are judged as more credible than victims displaying contained emotions or even positive feelings (Ask & Landström, 2010; Landström et al., 2019).

Another variable greatly impacting credibility judgment is the level of confidence shown by the sender during his/her statements. Since the early ‘70 s, the first theories on persuasion argued that the effectiveness of persuaders was directly proportional to the confidence they display in their positions (Scherer et al., 1973). Even though the variable investigated in their study was labeled as sender’s credibility, a first attempt to understand whether sender’s confidence may affect deception of detection and truthfulness was done by George and colleagues (2014). The authors verified whether and how people’s detection changes based on the perceived credibility of the sender and found that people are more prone to make not accurate judgments when the senders are not credible. In addition, although coming from a different research field, empirical evidence about autobiographical memory (e.g., witness memories, emotional/traumatic memories, flashbulb memories) widely investigated confidence in association with memory reports (e.g., Curci et al., 2020). In the forensic field, the persuasive effect of witnesses’ confidence on their credibility has been well-established (Wells et al., 1979). Witnesses exhibiting high confidence are generally judged as more accurate, and the risk of biased and mistaken overconfidence in memory reports may be contained if witnesses’ interviews were based on adequate non-suggestive techniques (Allwood et al., 2005; Granhag et al., 2004).

Alternatively, evidence that credibility judgments depend on verbal cues of the report comes from studies based on dual processes theories (e.g., Reinhard & Sporer, 2010, 2012; for a review see Köhnken & Steller, 1988). Specifically, the main assumption of these theories is that individuals make their judgments based either on the effortful or the effortless information processing modality. The first is used when people have high cognitive abilities and/or motivation and, thus, are able to rely on all relevant information coming from the statement (e.g., content; plausibility), by contrast the second mode is adopted when people have low cognitive abilities and/or motivation and, therefore, rely on heuristics and source cue information (e.g., sender’s attractiveness) or non-verbal cues. In addition, the credibility judgment of verbal reports is assumed to depend on the detector’s involvement, such that when people are in a high task involvement situation, they consider several types of information (e.g., verbal, non-verbal cues) to make their final truthful/deceptive judgment. For instance, Reinhard and collaborators’ (2008, 2010) found that people judged a statement as more credible when the statement was attractive, trustworthy, or plausible.

Overview of the current work

Across two studies, we aimed to investigate the extent to which judging and detecting deception and truthfulness are associated with the emotional content of written narratives and the level of confidence exhibited by the sender.

Therefore, we manipulated the level of the sender’s confidence of written deceptive and truthful narratives varying in emotional content. Specifically, Study 1 aimed to test the stimuli validity of the written narratives. Half of the pilot sample was administered a random sequence of eight deceptive vs. truthful narratives described with low confidence in memory across four emotional content conditions: emotional/bereavement vs. emotional/car accident vs. emotional/quarrel vs. neutral/holiday (low-confidence condition).Footnote 1 The other half was administered the same random sequence of eight narratives but described with high confidence in memory (high-confidence condition) (see the Measures section). Participants in both conditions were asked to evaluate each narrative in terms of emotional intensity, pleasantness, sender’s confidence, story plausibility, and richness of details.

Instead, Study 2, through an experimental design, aimed to investigate the role of sender’s confidence and emotional valence in judging and detecting deceptive vs. truthful written narratives. Half of the experimental sample was shown the above-mentioned low-confidence sequence of eight narratives (deceptive vs. truthful across the four emotional content conditions), and the other half was shown the above-mentioned high-confidence sequence of eight narratives (deceptive vs. truthful across the four emotional content conditions). All participants performed a veracity judgment task, and, for each narrative, they were asked to judge whether the sender was deceiving or telling the truth, and how confident they were of their own detection.

Study 1

Aims and hypotheses

The aim of Study 1 was to build and test the validity of the stimuli that would then be used in Study 2, namely a set of written narratives with varying emotional content. We, thus, asked a first sample of participants to write a series of narratives differing in terms of shown confidence in their recollection, veracity, and emotional content. Therefore, in order to check the validity of such stimuli, we asked a second sample of participants to rate the emotional intensity, pleasantness, sender’s confidence, story plausibility, and richness of details for each narrative. In accordance with the criteria used to build the stimuli, we expected that the emotional narratives (i.e., bereavement, car accident, and quarrel) would be judged as more emotionally intense and with lower pleasantness than the neutral narratives (i.e., holiday) (Hypothesis 1). Moreover, we expected that the low-confidence narratives would be rated lower than the high-confidence narratives in terms of the sender’s confidence score (Hypothesis 2). Finally, we expected no differences between narratives (i.e., low vs. high-confidence) in terms of story plausibility and richness of details (Hypothesis 3).

Method

Sample and design

Study 1 consisted of two phases: One for building the narratives, and the second for testing the validity of such narratives. The two phases were conducted online by using Google Modules platform. Three undergraduate students took care of the recruitment and data collection for the two phases of the study. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Department of XXXX and was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (protocol n° XXXX). Data collection started in May 2020 and ended in August 2020. Participants did not receive any compensation for taking part in the study.

Phase 1 was conducted in order to have a series of written narratives useful to be adopted as the main stimuli of Study 2. We recruited 22 participants (women = 65%, Mage = 30.95, SD = 10.02, range 23–57) who provided written either deceptive or truthful narratives of one of the four events differing in terms of emotional content (i.e., emotional: bereavement, car accident, quarrel, and neutral: holiday).Footnote 2 Moreover, each participant was asked to provide two versions of the same event: One version showing low-confidence and the other one with high-confidence in the recollection. More specifically, each participant was asked to provide two reports (i.e., low-confidence and high-confidence) by recalling (i.e., truthful narrative) or coming up with (i.e., deceptive narrative) one of the four events (i.e., bereavement, car accident, quarrel, and holiday).

Specific instructions were given in order to make the narratives as similar as possible in terms of confidence cues, details, and length (see Appendix). We collected 44 narratives from which we extracted 16 narratives -provided by 8 different senders. The selection was made in order to have one narrative for each event and by checking that the narratives complied with the provided instructions. To assure there was accordance among different raters, the selection was made by four undergraduates (XX, XX, XX, XX, and XX thanked in the acknowledgments). Thus, the final 16 narratives were divided into two different sequences with 8 narratives each. The two sequences differed in terms of the level of confidence in the recollection of the event, i.e., low vs high. In turn, each sequence was composed of half deceptive narratives and the second half truthful narratives.

During the second part of Study 1, a total of 144 participants (women = 50%, Mage = 37.65, SD = 13.37, range 20–58) took part in the study. A sensitivity power analysis for a dependent samples t-test indicated that N = 144 is sufficient to detect Cohen’s dz = 0.23 with 80% power. A second sensitivity power analysis for an independent samples t-test indicated that groups of n = 70 and n = 74 provide 80% power to detect Cohen’s ds = 0.42. No specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were adopted except for the variability in participants' age and gender. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two experimental conditions (narratives with low-confidence n = 70 vs. narratives with high-confidence n = 74). Participants had to read one of the two sequences of written narratives and judge each narrative in terms of emotional intensity, pleasantness, sender’s confidence, story plausibility, and richness of details. The two sequences were composed of 8 of the written narratives selected at the end of the first phase of this study (4 deceptive: bereavement, car accident, quarrel, and holiday and 4 truthful: bereavement, car accident, quarrel, and holiday). Thus, the study adopted a 2 × 2 × 4 mixed design with the type of the sequence (low-confidence vs high-confidence) as the between-subjects factor and the veracity (truthful vs deceptive) and the content of the narratives (bereavement vs car accident vs quarrel vs holiday) as the within-subjects factors. The dependent variables were: (i) Emotional intensity, (ii) pleasantness, (iii) sender’s confidence, (iv) story plausibility, and (v) richness of details indices.

Measures

Written narratives

Every participant provided two written narratives (i.e., low-confidence and high-confidence) of either one of the emotional (i.e., bereavement, car accident, quarrel) or neutral (i.e., holiday) events by either fabricating it (i.e., deceptive narrative) or genuinely recalling it (i.e., truthful narrative). Each participant reported the same event in two versions: One version showing low-confidence and the other one with high-confidence in the recollection.Footnote 3 Participants had to follow specific criteria to report the narratives allowing us to have narratives as similar as possible between each other in terms of length, expressions of (un)confidence, and richness of details (see also Appendix). In particular, participants had to write the report in first person by providing as many details as possible within maximum of 1500 words. The narratives should have reported the date, where the event took place, whether other people assisted with the event, the feelings and emotions experienced, the participant’s thoughts during the event, and other contextual details, such as the atmospheric conditions, smells, and noise. Moreover, a series of expressions—indicating either a high or low level of confidence—was provided. Specifically, for the high-confidence narrative expressions, such as “I am sure that”, “It surely happened that”, “I am certain that”, and “I precisely remember”, were provided. By contrast for the low-confidence narrative, the following examples were provided: “I am not so sure that”, “Maybe, it happened that”, “I think that”, and “I probably remember”. From a first set of 44 narratives, the authors selected 16 narratives, of which 8 high-confidence narratives (4 deceptive: bereavement, car accident, quarrel, and holiday and 4 truthful: bereavement, car accident, quarrel, and holiday) and 8 low-confidence narratives (4 deceptive: bereavement, car accident, quarrel, and holiday and 4 truthful: bereavement, car accident, quarrel, and holiday). The selection was made by checking whether the narratives were written in accordance with the instructions provided.

Procedure

Study 1 was composed of two phases. The first phase consisted of the creation of the written narratives. Specifically, a first sample of participants after providing their Informed Consent and their personal information (i.e., age, gender, education) were invited to write down two narratives (see Materials). The first phase was conducted online through the platform Google Modules and participants did not have any time limit. The second phase of Study 1 was carried out on a different sample of participants. After signing the Informed Consent and providing their personal information, participants were invited to read one of the two sequences of eight written narratives (i.e., low vs high-confidence narratives). Participants were instructed to rate each of the eight narratives in terms of (i) emotional intensity, (ii) pleasantness, (iii) sender’s confidence, (iv) story plausibility, and (v) richness of details indices on an 11-point scale (0 = ‘not at all’; 10 = ‘very much’) (Fig. 1).

Results

Before conducting the analyses, we calculated our scores of (i) emotional intensity and (ii) pleasantness, (iii) sender’s confidence, (iv) story plausibility, and (v) richness of details as follows and in accordance with the aim of our analyses. Because the aim of the pilot was to verify that participants had followed correctly our instructions while providing their narratives and, more precisely, that the emotional narratives did differ—in terms of emotional content—compared with the neutral narratives, we calculated two indices one for the emotional events (i.e., bereavement, car accident, and quarrel) and one for the neutral one (holiday) for the emotional intensity and pleasantness scores.Footnote 4 Therefore, we collapsed into one measure the scores reported by participants for the emotional events by calculating the average score of the three rates reported to the questions on the three emotional events. By contrast, for the scores of (iii) sender’s confidence, (iv) story plausibility, and (v) richness of details, we computed the total score for all the questions. However, for exploratory aims, we conducted analyses on the emotional intensity and (ii) pleasantness, (iii) sender’s confidence, (iv) story plausibility, and (v) richness of details by taking into account the full model of our study (see https://osf.io/6m5wc/).

Thus, in order to check whether the stimuli were correctly built with regard to their emotional content, we first run two paired samples Student’s t-tests corrected for multiple comparisons with the type of narrative (emotional vs neutral) as the paired variable on the two scores of (i) emotional intensity and (ii) pleasantness. Second, with the aim to verify our manipulation of the stimuli in terms of confidence, an independent samples Student’s t-test corrected for multiple comparisons was carried out with confidence (low vs high) of the written narratives as a between-subjects variable on the (iii) sender’s confidence, (iv) story plausibility, and (v) richness of details scores.

Emotional content

Regarding the emotional intensity score, we found a statistically significant difference between the two types of narratives, t(143) = 7.52, p < 0.001, dz = 0.63, 95% CI [0.45, 0.81]. In particular, the emotional narratives were evaluated as more emotionally intense (M = 6.64, SD = 1.39) than the neutral narrative (M = 5.33, SD = 2.18). In addition, we found a statistically significant difference between the narratives with regards to pleasantness, t(143) = -10.27, p < 0.001, dz = -0.85, 95% CI [-1.05, -0.67]. Specifically, the emotional narratives were assessed as less pleasant (M = 3.89, SD = 2.09) than the neutral narrative (M = 6.51, SD = 2.00). With regards to possible differences between truthful and deceptive narratives, we did not find any statistically significant difference neither on the emotional intensity score nor on the pleasantness, t(143) = 0.22, p = 0.82, d = -0.02, 95% CI [-0.18, 0.14] and t(143) = 1.76, p = 0.08, dz = -0.15, 95% CI [-0.31, 0.02], respectively.

Confidence, plausibility, and richness of details

With regards to the sender’s confidence score, the analysis showed a statistically significant difference between the two types of narratives, t(142) = 4.62, p < 0.001, ds = 0.77, 95% CI [0.43, 1.11]. In particular, participants reported a statistically higher score of sender’s confidence for the high-confidence narratives (M = 7.18, SD = 1.14) than for the low-confidence narratives (M = 6.22, SD = 1.35). Concerning the story plausibility score, we did not find any statistically significant difference between the low (M = 6.51, SD = 1.11) and high confidence narratives, (M = 6.74, SD = 1.07), t(142) = 1.26, p = 0.21, ds = 0.21, 95% CI [-0.12, 0.54]. By contrast, we found a statistically significant difference between narratives in terms of richness of details, t(142) = 2.41, p = 0.02, ds = 0.40, 95% CI [0.07, 0.73]. In particular, participants evaluated as more detailed the high-confidence narratives (M = 7.23, SD = 1.05) than the low-confidence narratives (M = 6.80, SD = 1.08).Footnote 5

Discussion

Study 1 was conducted with the aim to check whether the written narratives were suitable to be adopted as the main stimuli in Study 2. Collectively, the results sustained their use by showing that participants evaluated the written narratives as we expected in terms of emotional content, confidence, and plausibility.

To begin with, we found support for our expectations for the emotional intensity and pleasantness of the written narratives (Hypothesis 1). Indeed, we found that participants evaluated the narratives related to the three emotional events (i.e., bereavement, car accident, and quarrel) as more emotionally intense and less pleasant than the neutral event (i.e., holiday). In accordance with our expectations, this evidence underlines that indeed our narratives largely differed from each other in terms of emotional valence. In addition, we checked whether our manipulation of the level of confidence (i.e., low vs high) of the written narratives was correctly performed. Our analyses confirmed that the readers found the sender’s confidence lower for the low-confidence narratives than for the high-confidence narratives showing that the confidence expressions were inserted in the correct way (Hypothesis 2). Also, our results on the story plausibility confirmed our expectations (Hypothesis 3). Indeed, participants evaluated the plausibility of the stories with a similar rate both for the low and high-confidence narratives. Finally, we did not find support for our hypothesis on the richness of details score (Hypothesis 3). As a matter of fact, participants found the high-confidence narratives richer of details than the low-confidence ones. This is surprising as we directly selected the narratives (i.e., 16) from a larger sample of narratives (i.e., 44) taking into consideration the length and the number of details as inclusion and exclusion criteria. A possible explanation for these findings can be that participants recognized the high-confidence narratives as more detailed because of this higher confidence showed in these stories. That is, it might be that the expressions of confidence (e.g., “I am sure that”, “It surely happened that”, “I am certain that”, and “I precisely remember”) have increased the sense of richness in the narratives. However, despite this unexpected result, overall the evidence confirmed that our stimuli were constructed in an appropriate way, thus supporting their implementation in Study 2.

Study 2

Aims and hypotheses

The aim of Study 2 was to investigate the role of sender’s confidence and emotional content in judging and detecting deceptive vs. truthful written narratives. We hypothesized that emotional narratives (bereavement, car accident, and quarrel) recalled with high confidence in memory would be more frequently judged as truthful, regardless of the detection accuracy (Hypothesis 4). For exploratory purposes, we also examined the influence of sender confidence on receivers’ accuracy, as well as the extent to which receivers’ confidence predicted their accuracy.

Method

Design

Study 2 adopts a 2 × 2 × 4 mixed design with the sender’s Confidence (Low vs. High) as between-subjects variable, and the sender’s Veracity (Deceptive vs. Truthful) and the Emotional Message Content (Bereavement vs. Car accident vs. Quarrel vs. Holiday) as within-subjects variables. The dependent variables were (i) receiver veracity judgment, and (ii) accuracy and (iii) confidence in detecting truthful vs. deceptive narratives.

Sample

The sample consisted of 428 Italian volunteers (community sample, Caucasians, 50.7% women), aged between 20 and 60 (M = 35.59, SD = 10.86). The sample was randomly distributed across the two between-subjects conditions of the design (low-confidence n = 216 vs. high-confidence n = 212). The participants were recruited by adopting a snowball sampling method: Four undergraduates (XX, XX, XX, XX, and XX thanked in the acknowledgments) were involved in the procedure of sample recruitment. Each of them was asked to invite about 50 other participants and each of these was asked to invite about two more participants. The sample was recruited trying to keep variability in participants' age and gender, and to avoid the selection bias of recruiting only students, in order to prevent the unwanted effects of compliance, social desirability, or 'spurious' motivations underlying participation. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many Department labs were closed and many face-to-face activities were suspended. Therefore, participants were instructed that they would participate in research through individual one-by-one online meetings, using Teams, Zoom, Meet, or Skype. Participants were instructed that they would be asked to read and judge a sequence of written narratives. Participants were preliminarily presented with an informed consent form and a privacy policy statement. The study was given ethical approval by the XXXX and executed according to the Declaration of Helsinki (protocol n° XXXX). Participants gave written consent and at the end were fully debriefed. Data collection started in September 2020 and ended in January 2021.

After data were collected, using the simr package (Green & MacLeod, 2016) for R (R Core Team, 2016), we conducted a simulation-based power analysis to determine the sensitivity of this design, given the sample size and estimated random effect structure (derived from the retained model predicting veracity judgments described in the Results). We assessed how much power the present study had to detect a series of log odds ratios of varying sizes, specifically for a two-way interaction. The simulation suggested that the present study had 19.6% for LOR = 0.20 (d = 0.11), 42.4% for LOR = 0.40 (d = 0.22), 81.6% for LOR = 0.60 (d = 0.33), 98.0% for LOR = 0.80 (d = 0.44), 100.0% for LOR = 1.00 (d = 0.55), and 100.0% for lor = 1.20 (d = 0.66). Each power estimate was based on 250 simulations. Although there is no clear empirical benchmark for effect sizes on this topic, for context, Bond and DePaulo (2006) estimated that overall lie-truth discrimination produces an effect of approximately d = 0.40. These results suggest that the present study had sufficient power to detect plausible effects but inadequate power for the smallest of effects.

Measures and procedure

Each participant was asked to perform the task during a one-by-one online meeting, by using one of the following platforms: Teams, Zoom, Meet, or Skype. Participants were tested individually and were randomly instructed to read one of the two sequences of written narratives adopted in the pilot study. Participants did not have a time limit to read the narrative and were invited to read them silently. Therefore, one group of participants (i.e., low-confidence condition) was instructed to read the sequence of eight narratives (4 deceptive: bereavement, car accident, quarrel, and holiday and 4 truthful: bereavement, car accident, quarrel, and holiday) described with low confidence; instead, the second group of participants (i.e., high-confidence condition) was instructed to read the sequence described with high confidence (4 deceptive: bereavement, car accident, quarrel, and holiday and 4 truthful: bereavement, car accident, quarrel, and holiday) (see pilot Study 1). After reading, all participants performed a lie-detection task and, for each narrative, they were asked to judge whether the sender was lying or telling the truth (deceptive vs. truthful), and how confident they were of their own detection on an 11-point scale (0 = ‘not at all confident’; 10 = ‘very confident’). We were mainly interested in three measured variables: (i) receivers’ veracity judgments (0 = lie, 1 = truth), (ii) receivers’ judgment accuracy (0 = incorrect, 1 = correct), and (iii) receivers’ judgment confidence.

Results

Further detail for reported analyses, as well as for additional robustness checks and for rejected models, is available in Supplemental Material on OSF (https://osf.io/6m5wc/). Code for reproducing the analyses is available on GitHub (https://github.com/RabbitSnore/deception-confidence-and-bias).

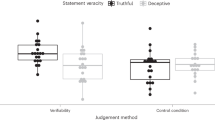

Does sender confidence influence receiver veracity judgments?

Our primary research question concerned the extent to which the confidence with which senders communicate influences receivers’ veracity judgments (i.e., whether receivers judge narratives as truthful or deceptive), for different types of message content. To address this question, we fit a series of mixed effects logistic regression models using the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2014) for R (R Core Team, 2016). These models allow us to examine the extent to which response bias might be influenced by sender confidence and the emotional content of the message. To select a model for interpretation, we fit more complex models and compared them sequentially. Each step in the sequence added predictors and interaction terms, approaching the highest order interactions possible in the design (i.e., three-way interactions). First, we fit a model in which veracity judgments (0 = lie, 1 = truth) were predicted by actual sender veracity (deceptive vs. truthful) and by emotional message content (holiday, bereavement, accident, and quarrel; dummy coded with holiday as the reference group), as well as random intercepts for receivers and for senders, and random slopes for veracity for each receiver. We then fit a model that added sender confidence (low vs. high) and another model that added the interaction between sender confidence and each message content type. Following that, we fit a model that added the remaining two-way interactions between sender veracity, emotional message content, and sender confidence, as well as a model adding the three-way interactions between those variables. These models used data from N = 428 judges providing a total of N = 3,424 judgments.

We compared the five models using likelihood ratio tests to find a model retain for interpretation. Adding confidence condition significantly improved the model, χ2 (1) = 7.98, p = 0.005, AIC 4549.2 vs. 4543.2, and adding the interaction terms between sender confidence and emotional message content further improved the model, χ2 (3) = 16. 80, p = 0.0008, AIC 4543.2 vs. 4532.4. Adding the remaining two-way interactions was a significantly better fit with the data, χ2 (4) = 22.55, p = 0.0002, AIC 4532.4 vs. 4517.9, but the three-way interactions did not, χ2 (3) = 5.23, p = 0.156, AIC 4517.9 vs. 4518.6. Thus, we retained the model with all the two-way interaction terms. A summary of this model is presented in Table 1.

As can be seen in Table 1, the coefficient for sender confidence was significant and positive, indicating that more confident senders were viewed as more likely to be truthful when talking about holidays. Additionally, the interaction terms for sender confidence with accident messages and with quarrel messages were significant and negative. More precisely, the results suggest that sender confidence had little or no effect on receivers’ veracity judgments for messages about accidents. By contrast, higher sender confidence was associated with fewer truth judgments for messages about quarrels. In short, the confidence with which senders presented their stories appeared to influence receivers’ veracity judgments, but this relationship was moderated by the content of the message. That is the effect of senders’ confidence was strictly related to the type of event presented in the narrative. Additionally, sender veracity significantly interacted with emotional message content, such that truthful messages about bereavements and quarrels were more likely to be judged as truths, compared to messages about holidays. Table 2 displays the raw rates of truth judgments as well as mean predicted truth judgment rates derived from the retained model for each condition. These values are also illustrated in Fig. 2.

As an additional robustness check, we calculated signal detection indices for each receiver, and we fit a linear regression model predicting c (a measure of response bias) using sender confidence. Consistent with the analyses above, sender confidence significantly predicted response bias, b = 0.11 [0.03, 0.19], t (426) = 2.75, p = 0.006, such that receivers became more truth biased when senders were more confident.

Exploratory analyses

Does sender confidence influence receiver accuracy?

Overall, receivers’ judgments were accurate at a level close to chance (52.5%). To examine how sender confidence might influence receiver accuracy (i.e., whether the judgment of deception or truthfulness were accurate or not), we followed an approach highly similar to how we addressed the research question about veracity judgments. We fit a series of mixed effects logistic regression models, adding predictors in the same sequence described above, and compared them using likelihood ratio tests to identify a model to retain for interpretation. We found that adding sender confidence as a predictor did not significantly improve the model, χ2 (1) = 0.01, p = 0.940. AIC 4555.8 vs. 4557.8. Adding the interaction between sender confidence and emotional message content also did not significantly improve the model, χ2 (3) = 5.76, p = 0.124, AIC 4557.8 vs. 4558.1. However, adding the two-way interactions between content and veracity offered a significantly better fit, χ2 (4) = 36.76, p < 0.0001, AIC 4558.1 vs. 4529.3, and adding the three-way interactions between content, veracity, and sender confidence provided further improvement, χ2 (3) = 16.67, p = 0.0008, AIC 4529.3 vs. 4518.6. We, therefore, retained the final model containing the three-way interactions. This model is summarized in Table 3.

In the retained model, the coefficient for sender veracity was significant and positive, indicating that for messages about holidays, receivers judged truthful messages more accurately. The coefficient for sender confidence was significant and negative, suggesting a decrease in accuracy for messages about holidays when senders communicated more confidently. The significant interaction between sender confidence and sender veracity indicates that this increase was especially pronounced for truthful holiday messages communicated confidently. We also see significant increases in accuracy for messages about accidents and about quarrels. Accuracy for deceptive messages about quarrels was further, though only moderately, increased when senders conveyed their messages more confidently. Finally, the significant three-way interactions indicate that the improvement in accuracy conferred by sender confidence observed for messages for holidays was mitigated for messages about accidents and quarrels. Raw accuracy rates and mean predicted accuracy rates derived from the retained model for each condition are displayed in Table 4, and they are also illustrated in Fig. 2. Given the pattern of response biases we observed above, all these changes in accuracy are likely largely the result of shifting response bias, rather than improved discrimination.

Additionally, we calculated signal detection indices for each receiver, and we fit a linear regression model predicting d’ using sender confidence. In this model, sender confidence was not a significant predictor of d’, b = 0.011 [-0.130, 0.151], t (426) = 0.150, p = 0.881. Given that d’ measure truth-deception discrimination, disentangled from response bias, these results indicate that sender confidence did not appear to influence receivers’ ability to correctly distinguish between lies and truth, across the four content types. Rather, consistent with the above analyses, changes in receivers’ accuracy as a function of sender confidence appears to be primarily the result of changes in response bias.

Does receiver confidence predict receiver accuracy?

We assessed whether a receiver’s confidence predicted their accuracy with two approaches. First, we fit a mixed effects logistic regression model with accuracy predicted by confidence, with random intercepts for senders and receivers. In this model, receiver confidence was not a significant predictor of receiver accuracy, b = 0.007 [-0.032, 0.046], z = 0.35, p = 0.727. The upper bound of the 95% confidence interval for this estimate excludes effects larger than the equivalent of d = 0.025 – a negligible effect. Additionally, we fit a model in which we added receiver confidence as a predictor to the retained model predicting accuracy (reported above; see Table 3). A likelihood ratio test indicated that this model failed to outperform the retained model, χ2 (1) = 0.35, p = 0.986. Adding an interaction term for receiver confidence and sender confidence similarly failed to outperform the previous model, χ2 (1) = 2.08, p = 0.149. Thus, there was no evidence that confidence meaningfully predicted accuracy.

Discussion

Contrary to our expectations (Hypothesis 4), when senders conveyed their messages more confidently, receivers judged them to be more credible when they were speaking about holidays or bereavements, but this effect was mitigated or inverted for accidents and quarrels. Rather than being a function of the emotionality of the content, one possible interpretation is that sender confidence may interact with the self-presentational incentives implied by the message content (Bond et al., 2013). That is, senders might be particularly motivated to portray themselves in a positive light when discussing accidents and quarrels, and receivers may detect this motivation and thus be less persuaded by displays of confidence since they recognize this confidence as potentially strategic rather than authentic.

Receivers’ deception detection accuracy varied as a function of sender confidence, sender veracity, and message content. These patterns of changes suggested that sender confidence mainly influences accuracy by changing response bias. That is, sender confidence indirectly influences receivers’ accuracy rates, not by making them more discerning, but by making receivers more or less inclined to judge a message as truthful (regardless of its actual veracity).

We also observed that sender veracity interacted with message content to influence receivers’ veracity judgments. Differing from the other types of message content, truthful messages about quarrels were especially likely to be judged as truthful, and deceptive messages about quarrels were more likely to be judged as deceptive. The cause of this pattern is somewhat unclear, given the small sample of available senders, but one possibility is that the veracity of messages about some topics is especially transparent. This interpretation is consistent with past research that indicates that senders (and the situations in which they send their messages) are principally responsible for the observed variation in both accuracy and bias (Bond & DePaulo, 2008).

The ratio of estimated sender variance to receiver variance provides information about the relative contribution of senders and receivers to the accuracy and bias of veracity judgments. We can examine the variance components from models predicting judgments and accuracy only using random intercepts for senders and receivers. For veracity judgments, sender variance is 5.99 times larger than receiver variance (0.205/0.034). That is, sender variance was nearly twice as large as receiver variance. For accuracy, estimated receiver variance was 0, and estimated sender variance was 0.273. Thus, this model estimated that senders were entirely responsible for the variance in accuracy.Footnote 6 Consistent with previous research, in the present study, differences across senders accounted for a substantial amount of that variation in veracity judgments and the vast majority of variance in accuracy. Indeed, for accuracy, receivers were practically fungible.

General discussion

In the present manuscript, we presented two studies aiming to verify whether sender’s confidence shown while narrating either a deceptive or truthful event could influence receiver’s ability in deception and truthfulness judgements. We further aimed to investigate this issue by taking into account the emotional valence of the narratives. Therefore, we first ran Study 1 to create a series of deceptive and truthful narratives differing for sender’s confidence (low vs high) and emotional content (emotional: Bereavement vs. car accident vs. quarrel and neutral: Holiday). Then, to test the validity of such narratives in terms of emotional intensity and pleasantness and sender’s confidence. In Study 2, we explored our main question on the influence of senders’ confidence on receiver’s veracity judgements by asking participants to provide their judgements on the pool of narratives of Study 1 with regards to the veracity of the narratives and the confidence of their own judgement. The main findings of both studies can be summarized as follows.

In line with our predictions (Hypothesis 1), our findings on the assessment of the emotional deceptive and truthful narratives demonstrated that the narratives did differ in terms of emotional content. Participants reported higher emotional intensity scores for the narratives describing bereavement, car accident, and quarrel than the ones on holidays. Similarly, and again in accordance with our expectation (Hypothesis 2), participants evaluated sender’s confidence consistently with our manipulation. In other words, participants recognized a low level of sender’s confidence for the narratives characterized by expressions of low confidence (e.g., “I am not sure that”, “It probably happened that”, etc.) and vice versa. Both these findings assured that the narratives were constructed accordingly to our purpose and supported their implementation in Study 2.

Our results on the core research question on the influence of sender’s confidence in receiver’s veracity judgements revealed an interesting pattern of results. In line with prior evidence showing that emotional features and language manifestations are two criteria adopted by receivers to judge the veracity of statements (e.g., Curci et al., 2019), we expected that receivers would judge as truthful the emotional and highly confident narratives, even when they were neutral and deceptive. However, our data partially confirmed our prediction (Hypothesis 4) as the high confidence made people more prone to judge the narratives as truthful for neutral events (i.e., holidays) and only one emotional event (i.e., bereavements), thereby suggesting that sender’s confidence does not directly influence receiver’s veracity judgements. This was also found for the emotional content of the narratives. Participants were more likely to recognize as truth the truthful narratives on bereavements and quarrels than the ones on holidays. These results resemble Kaufmann and colleagues (Kaufmann et al., 2003) findings on the influence of emotions on people’s credibility judgements. However, we did not detect an effect of the emotional content with regard to the narratives describing car accidents. This suggests that when people have to make veracity judgments on emotional events do not only consider the emotions associated with the event but also the kind of event. Noteworthy, both sender’s confidence and the narrative emotional content do not have a main effect on receiver’s veracity judgments rather it is their interaction that impacts judgments. Indeed, a high sender’s confidence made receivers judge: (i) bereavements and holidays narratives as truthful and (ii) quarrels narratives as deceptive. These findings are opposite to a previous study investigating whether witnesses’ confidence affected individuals’ ability to detect deception (Tetterton & Warren, 2005). As a matter of fact, the authors detected a direct effect of witnesses’ confidence on deception: High-confidence testimonies were rated as more truthful than low-confidence testimonies and this effect was even stronger for false testimonies than true ones. However, we can speculate the following. Receivers interpret sender’s confidence differently based not only on the emotional valence of the event but also on other characteristics related to the sender’s personal investment in the described event. That is, when the sender described events that involved possible interactions between people (e.g., holidays and quarrels) and, thus, the sender played a “responsible/active” role, receivers perceived—and judged—the high confidence as an indicator of truthfulness for the neutral event (i.e., holiday), and of deception for the negative one (i.e., quarrel). Contrarily, when the sender reported an event in which he/she potentially played a “victim/passive” role (i.e., bereavement) because of no interaction between people, receivers recognized the high confidence as an indicator of truthfulness. Future studies need to investigate whether indeed sender’s involvement in the event impacts receiver’s veracity judgments.

Furthermore, we looked at receiver’s accuracy to further understand (Exploratory Analyses) whether sender’s confidence and the narrative’s emotional content could play a role in the classical truth bias (e.g., Levine & Bond, 2014; Levine et al., 1999). We found that the overall receiver’s accuracy was 52.5%, a percentage close to the one underlined by Bond and DePaulo (2006). Moreover, receiver’s accuracy depended on sender’s veracity and confidence. Specifically, the accuracy for truthful narratives with high sender’s confidence on holidays was higher than for the other narratives as well as the accuracy for deceptive narratives with high sender’s confidence on car accidents and quarrels was moderately higher than for the rest of the narratives. First, these results appear to be not completely supportive of an emotional truth bias (Peace & Sinclair, 2012). Indeed, even if we did find a higher accuracy for the neutral events than for the emotional ones, this was true only for truthful narratives. Second,—based on the results on response biases—the increase in receiver’s accuracy due to sender’s confidence does not reflect a concrete better ability to differentiate between truthful and deceptive narratives, but rather a change in receivers’ proneness to judge as truthful the pool of narratives. Also, this result contrasts what was previously found by Tetterton and Warren (2005). In two studies, the authors found a significant effect of confidence on deception detection accuracy, such that people were more prone to wrongly believe that deceptive stories were truthful when actually they were not.

This pattern of results can be informative about the use of verbal cues in discriminating truthful statements from deceptive statements. As a matter of fact, especially in recent years, researchers support the use of verbal cues (e.g., richness of details, types of details reported, plausibility of the story) -instead of nonverbal cues (e.g., emotions, behaviors displayed by the sender)- in spotting truth and lies because to report their experiences truth-tellers would adopt different verbal strategies than deceptive people (e.g., Vrij, 2019; Vrij & Granhag, 2012). For instance, in the Verifiability Approach (VA; Nahari et al., 2014), it is assumed that the amount of details and type of details provided by liars and truth-tellers differs such that (i) liars overall report more details than truth-tellers but (ii) truth-tellers provide more checkable details (i.e., details that can be supported by external evidence) than liars. Similarly, the Strategic Use of Evidence approach (SUE; Granhag & Hartwig, 2015) presupposes that consistency in answering questions during an interview can be an indicator of truthfulness or deception: Liars provide less consistent information when confronted with incriminating evidence compared to truth-tellers. Still, another recent verbal cues model is the Model Statement (Vrij, 2008) which suggests considering the plausibility of information rather than the quantity of provided information with the assumption that truth-tellers would report more plausible details than liars. Finally, one well-known and widely used method is the Criteria Based Content Analysis (CBCA; Köhnken & Steller, 1988). This method is based on the detection of nineteen criteria (i.e., verbal cues such as the structure of the report, quantity of details, contextual information, spontaneous corrections, admission lack of memory, or doubts about one’s own report) supposed to be indicative -when absent- of deception. Collectively, all these approaches have been supporting the implementation of verbal cues in detecting lies and, in turn, making accurate veracity judgments. Our findings do provide further information on the possible use of sender’s confidence as an effective verbal cue showing that the implementation of this criterion can be problematic as it does not facilitate the correct detection of truthful and deceptive messages, even if it can indirectly affect individuals’ veracity judgements.

Limitations

Some caveats need to be pointed out. First, for both our samples the age range was restricted, thus undermining the possibility to generalize our findings to older people. In addition, the limited number of senders we used imposes limitations on the strength of our conclusions about the relative contribution of senders versus receivers to accuracy and bias, and the limited sample size raises some concerns about the extent to which the present results would be robust and replicable in other samples. Indeed, recently, Levine et al. (2022) underlined the importance of having an adequate number of judgments to have good data stability recommending at least 500 judgments. Our study largely followed this recommendation. However, despite this, it is also important to acknowledge that Levine and colleagues stressed the idea that the high number of judgments should not be due only to an elevate number of judges but should be the result of the multiplication of a high number of both senders and judges. In our study, the number of senders was relatively small (i.e., 8), hence future investigations of the present research questions should employ larger samples of senders. Moreover, we built a between-subjects design because the 8 senders provided two versions of the same event (i.e., low and high confidence). However, some scholars have argued that for studies investigating judgments it is better to employ within-subjects design (e.g., Birnbaum, 1999). Future studies should consider this issue. Noteworthy, while testing our narratives, participants reported to perceive high confidence narratives as more detailed than the low confidence narratives, even if the narratives did not differ in terms of richness of details. Participants also evaluated the emotional and neutral narratives divergently in terms of richness of details, plausibility, and confidence scores, such that neutral events reported higher scores than emotional ones. Therefore, our results need to be read considering the possibility that senders’ confidence made participants perceiving the narratives differently in terms of richness of details. Future studies could also consider including in their design an additional narrative with a positive valence. Including this additional level of the variable could help in elucidating the role of emotional content on people’s veracity judgments. Similarly, the inclusion of a continuous scale -instead of a dichotomous option- to measure veracity judgments could be beneficial for future studies in order to better clarify the degree of certainty of individuals’ judgments. Finally, considering the practical implications of this work for the legal field, our samples of senders and receivers might be not representative of legal actors, such as, for instance, judges and jurors as well as suspects and witnesses. Relatedly, in order to isolate the influence of senders’ confidence on receivers’ veracity judgements, we employed written narratives. However, in real situations (e.g., interviewing and interrogation), veracity judgments mainly occur in vis-a-vis interactions during which other variables can be considered by the receivers to make their judgments. Next experiments may consider using more natural stimuli in different mediums (e.g., video recordings), to assess whether other variables can affect the relationship between sender’s confidence and receiver’s veracity judgment.

Implications

The practical implications of the current findings clearly lie in the legal realm. Oftentimes, during legal proceedings, practitioners have the challenging task to understand whether suspects, witnesses, and victims are providing truthful or deceptive statements. This task becomes particularly difficult when the legal practitioners do not have any additional sources but rather can only rely on the people’s statements during interviews and/or interrogations. It is well-known that, in these situations, the human ability to detect lies and truth is just above chance levels, and people generally base their judgments by taking into consideration the interviewee’s characteristics and the statement’s verbal cues. The present work tried to answer the need to extend previous research on lie detection and verbal cues by investigating whether sender’s confidence can influence the detection accuracy for emotional narratives. Our evidence underlines that also the confidence shown by the sender does not help in accurate detection, further suggesting the need for legal practitioners to have scientific-based criteria for making accurate veracity judgments.

Data Availability

The authors are willing to provide the data under request.

Notes

The valence of our narratives is in line with prior research (e.g., Peace & Porter, 2011).

Despite the young average age of our participants, all of them were able to recall events as requested. Therefore, we did not need to exclude any participants from our Study.

The choice to ask each participant to provide two versions of the same event was made in order to control sender’s narrative style.

Cronbach’s alpha for the emotional intensity and pleasantness scores of emotional events were .67 and .86, respectively.

Although not related to the primary aim of our pilot study, we run additional analyses to further check our stimuli. Specifically, we computed a pool of paired sample Student’s t-test on confidence, plausibility, and richness of details with the type of narrative as paired variable. We found the following effect: t(143) = 6.27, p < .001, d = -0.52, 95% CI [-.70, -.35], t(143) = 7.71, p < .001, d = -0.64, 95% CI [-.46, -.82], and t(143) = 1.41, p = .16, d = -0.12, 95% CI [-.18, .46], respectively.

The reader may notice that these variance estimates differ substantially from those in the retained models. The retained models estimate sender variance to be much smaller because there are so few senders in the sample (i.e., 8), so any variance attributable to them is suppressed by the fixed effects and their interactions.

References

Allwood, C. M., Ask, K., & Granhag, P. A. (2005). The cognitive interview: Effects on the realism in witnesses’ confidence in their free recall. Psychology, Crime & Law, 11(2), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160512331329943

Ask, K., & Landström, S. (2010). Why emotions matter: Expectancy violation and affective response mediate the emotional victim effect. Law and Human Behavior, 34(5), 392–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-009-9208-6

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2014). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. arXiv preprint arXiv:1406.5823.

Birnbaum, M. H. (1999). How to show that 9> 221: Collect judgments in a between-subjects design. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 243. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.3.243

Bond, C. F., Jr., & DePaulo, B. M. (2006). Accuracy of deception judgments. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 214–234. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_2

Bond, C. F., Jr., & DePaulo, B. M. (2008). Individual differences in judging deception: accuracy and bias. Psychological Bulletin, 134(4), 477.

Bond, C. F., Jr., Howard, A. R., Hutchison, J. L., & Masip, J. (2013). Overlooking the obvious: Incentives to lie. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(2), 212–221.

Brashier, N. M., & Marsh, E. J. (2020). Judging truth. Annual review of psychology, 71(1).

Caso, L., Palena, N., Carlessi, E., & Vrij, A. (2019). Police accuracy in truth/lie detection when judging baseline interviews. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 26(6), 841–850. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2019.1642258

Curci, A., Lanciano, T., Battista, F., Guaragno, S., & Ribatti, R. M. (2019). Accuracy, confidence, and experiential criteria for lie detection through a videotaped interview. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 748. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00748

Curci, A., Lanciano, T., Curtotti, D., & Sartori, G. (2020). Lessons for the courtroom from the study of Flashbulb memory: An integrative review. Memory, 28(3), 441–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2020.1727522

Dechêne, A., Stahl, C., Hansen, J., & Wänke, M. (2010). The truth about the truth: A meta-analytic review of the truth effect. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(2), 238–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309352251

Donovan, J. J., Dwight, S. A., & Hurtz, G. M. (2003). An assessment of the prevalence, severity, and verifiability of entry-level applicant faking using the randomized response technique. Human Performance, 16(1), 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327043HUP1601_4

Gingo, M., Roded, A. D., & Turiel, E. (2020). What they don’t know won’t hurt them: Parents’ judgments about lying to their adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12503

George, J. F., Tilley, P., & Giordano, G. (2014). Sender credibility and deception detection. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 1–11.

Granhag, P. A., & Hartwig, M. (2015). The strategic use of evidence (SUE) technique: A conceptual overview. In P. A. Granhag, A. Vrij, & B. Verschuere (Eds.), Deception detection: Current challenges and new approaches (pp. 231–251). Wiley.

Granhag, P. A., Jonsson, A. C., & Allwood, C. M. (2004). The cognitive interview and its effect on witnesses’ confidence. Psychology, Crime and Law, 10(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1071

Green, P., & MacLeod, C. J. (2016). SIMR: An R package for power analysis of generalized linear mixed models by simulation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 7(4), 493–498.

Hartwig, M., & Bond, C. F., Jr. (2011). Why do lie-catchers fail? A lens model meta-analysis of human lie judgments. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 643. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023589

Hauch, V., Sporer, S. L., Michael, S. W., & Meissner, C. A. (2016). Does training improve the detection of deception? A meta-analysis. Communication Research, 43(3), 283–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650214534974

Henderson, E. L., Simons, D. J., & Barr, D. J. (2021). The trajectory of truth: A longitudinal study of the illusory truth effect. Journal of Cognition, 4(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.5334/joc.161

Kaufmann, G., Drevland, G. C., Wessel, E., Overskeid, G., & Magnussen, S. (2003). The importance of being earnest: Displayed emotions and witness credibility. Applied Cognitive Psychology: The Official Journal of the Society for Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 17(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.842

Köhnken, G., & Steller, M. (1988). The evaluation of the credibility of child witness statements in the German procedural system. Issues in Criminological & Legal Psychology, 13, 37–45.

Lanciano, T., Luke, T.J., Guaragno, S., Ribatti, R., & Curci, A. (under review). Does being emotionally intelligent and empathic predict deception detection accuracy? Applied Cognitive Psychology.

Landström, S., Ask, K., & Sommar, C. (2019). Credibility judgments in context: Effects of emotional expression, presentation mode, and statement consistency. Psychology, Crime & Law, 25(3), 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2018.1519828

Levine, T. R. (2014). Truth-default theory (TDT) a theory of human deception and deception detection. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 33(4), 378–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X14535916

Levine, T. R., & Bond, C. F. (2014). Direct and indirect measures of lie detection tell the same story: A reply to ten Brinke, Stimson, and Carney (2014). Psychological Science, 25(10), 1960–1961. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614536740

Levine, T. R., Park, H. S., & McCornack, S. A. (1999). Accuracy in detecting truths and lies: Documenting the “veracity effect.” Communications Monographs, 66(2), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759909376468

Levine, T. R., Daiku, Y., & Masip, J. (2022). The number of senders and total judgments matter more than sample size in deception-detection experiments. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(1), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691621990369

Levine, T. R., Serota, K. B., Shulman, H., Clare, D. D., Park, H. S., Shaw, A. S., ..., & Lee, J. H. (2011). Sender demeanor: Individual differences in sender believability have a powerful impact on deception detection judgments. Human Communication Research, 37(3), 377–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2011.01407.x

Luke, T. J. (2019). Lessons from Pinocchio: Cues to deception may be highly exaggerated. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(4), 646–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619838258

Luo, M., Hancock, J. T., & Markowitz, D. M. (2022). Credibility perceptions and detection accuracy of fake news headlines on social media: Effects of truth-bias and endorsement cues. Communication Research, 49(2), 171–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220921321

McCornack, S. A., & Parks, M. R. (1986). Deception detection and relationship development: The other side of trust. Annals of the International Communication Association, 9(1), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.1986.11678616

Melchers, K. G., Roulin, N., & Buehl, A. K. (2020). A review of applicant faking in selection interviews. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 28(2), 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12280

Nahari, G., Vrij, A., & Fisher, R. P. (2014). The verifiability approach: Countermeasures facilitate its ability to discriminate between truths and lies, countermeasures facilitate its ability to discriminate between truths and lies. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28, 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2974

Park, H. S., & Levine, T. (2001). A probability model of accuracy in deception detection experiments. Communication Monographs, 68(2), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750128059

Park, H. S., & Levine, T. R. (2017). The effects of truth–lie base-rates on deception detection accuracy in Korea. Asian Journal of Communication, 27(5), 554–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2017.1334074

Peace, K. A., & Porter, S. (2011). Remembrance of lies past: A comparison of the features and consistency of truthful and fabricated trauma narratives. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25(3), 414–423.

Porter, S., Peace, K. A., & Emmett, K. A. (2007). You protest too much, methinks: Investigating the features of truthful and fabricated reports of traumatic experiences. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 39(2), 79. https://doi.org/10.1037/cjbs2007007

Reinhard, M. A., & Sporer, S. L. (2010). Content versus source cue information as a basis for credibility judgments. Social Psychology.

Reinhard, M. A. (2010). Need for cognition and the process of lie detection. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(6), 961‐971.

Reinhard, M. A., & Sporer, S. L. (2008). Verbal and nonverbal behaviour as a basis for credibility attribution: The impact of task involvement and cognitive capacity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(3), 477–488.

Reinhard, M. A., Sporer, S. L., & Scharmach, M. (2012). Perceived familiarity with a judgmental situation improves lie detection ability. Swiss Journal of Psychology.

R Core Team. (2016). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria

Scherer, K. R., London, H., & Wolf, J. J. (1973). The voice of confidence: Paralinguistic cues and audience evaluation. Journal of Research in Personality, 7(1), 31–44.

Schwarz, N., Van Lange, P., Kruglanski, A., & Higgins, E. T. (2011). Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 289–308).

Street, C. N., & Masip, J. (2015). The source of the truth bias: Heuristic processing? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56(3), 254–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12204

Tenenbaum, J. B., Griffiths, T. L., & Kemp, C. (2006). Theory-based Bayesian models of inductive learning and reasoning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(7), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.05.009

Tetterton, V. S., & Warren, A. R. (2005). Using witness confidence can impair the ability to detect deception. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 32(4), 433–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854805276406

Trifiletti, E., D’Ascenzo, S., Lugli, L., Cocco, V. M., Di Bernardo, G. A., Iani, C., ..., & Vezzali, L. (2020). Truth and lies in your eyes: Pupil dilation of White participants in truthful and deceptive responses to White and Black partners. Plos one, 15(10), e0239512. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239512

Unkelbach, C., & Rom, S. C. (2017). A referential theory of the repetition-induced truth effect. Cognition, 160, 110–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2016.12.016

Verigin, B. L., Meijer, E. H., Bogaard, G., & Vrij, A. (2019). Lie prevalence, lie characteristics and strategies of self-reported good liars. PloS One, 14(12), e0225566. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225566

Vrij, A. (2019). Deception and truth detection when analyzing nonverbal and verbal cues. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 33(2), 160–167.

Vernham, Z., Vrij, A., Nahari, G., Leal, S., Mann, S., Satchell, L., & Orthey, R. (2020). Applying the verifiability approach to deception detection in alibi witness situations. Acta Psychologica, 204, 103020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2020.103020

Vrij, A. (2008). Nonverbal dominance versus verbal accuracy in lie detection: A plea to change police practice. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35(10), 1323–1336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854808321530

Vrij, A., & Granhag, P. A. (2012). Eliciting cues to deception and truth: What matters are the questions asked. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 1, 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2012.02.004

Wells, G. L., Lindsay, R. C., & Ferguson, T. J. (1979). Accuracy, confidence, and juror perceptions in eyewitness identification. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64(4), 440. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.64.4.440

Zimmerman, T., Njeri, M., Khader, M., Allen, J., Rosellini, A., & Eaves, T. (2020). A review of truth-default theory: Implications for information behavior research. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 57(1), e312. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.312

Zuckerman, M., DePaulo, B. M., & Rosenthal, R. (1981). Verbal and nonverbal communication of deception. In Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 14, pp. 1–59). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60369-X

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help of Andriani Stefania, Di Roma Ferdinando, Gammino Matteo, La Corte Claudia, Lacaita Daniele, Petrignani Marika, Pignatelli Pietro, and Santopietro Roberta for their collaboration in collecting the data and scoring the protocols.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TL and FB conceived the study. TL and FB collected data. TJL and FB analyzed the data. TL, FB, and TJL wrote the manuscript. AC critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors (TL, TJL, AC, and FB) declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

True and high-confidence event

We now ask you to describe a bereavement/car accident/quarrel/holiday that you actually experienced in the last 18 months in the space below. You should describe the event as much detailed as possible, inserting details such as when it happened, the hour, where you were, who you were with, what you were doing, the emotions you felt, the thoughts that popped in your mind, and others details (e.g., details of the context, smells, sounds, etc.). In addition, we want that you show high confidence while describing such an event. For instance, you could use expressions like “I am sure that”, “It surely happened that”, “I am certain that”, and “I precisely remember”. You have to describe the event by imagining to be telling it to another person.

True and low-confidence event

We now ask you to describe a bereavement/car accident/quarrel/holiday that you actually experienced in the last 18 months in the space below. You should describe the event as much detailed as possible, inserting details such as when it happened, the hour, where you were, who you were with, what you were doing, the emotions you felt, the thoughts that popped in your mind, and others details (e.g., details of the context, smells, sounds, etc.). In addition, we want that you show low confidence while describing such an event. For instance, you could use expressions like “I am not so sure that”, “Maybe, it happened that”, “I think that”, and “I probably remember”. You have to describe the event by imagining to be telling it to another person.

False and high-confidence event