Abstract

Pregnancy and/or the puerperium involve social, physiological and psychological changes that make women more vulnerable to mental disorders such as anxiety and depression, even more so if these develop in stressful contexts such as the pandemic. The aim of this study is to identify factors associated with the risk of postpartum anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. A cross-sectional study was conducted among postpartum women (n = 69) who gave birth between March 2020 and March 2021 in Melilla, a Spanish cross-border city with Morocco whose borders were closed, making it a confined city. The scales used were the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Results reported an elevated risk of depression (85.5%) and anxiety (63.8%), with severe anxiety reaching 40.6% of cases. Predictors of postpartum depression comprised a personal history of mood disorders (β = 8.421; CI95% = 4.863/11.978) and having been diagnosed with COVID-19 during pregnancy or postpartum (β = 4.488; CI95% = 1.331/7.646). As regards anxiety, it is predicted on the basis of mood antecedents (β = 14.175; CI95% = 7.870/20.479), the fact of having been diagnosed with COVID-19 during pregnancy or postpartum (β = 8.781; CI95% = 2.970/14.592) and the fact of being a multipara (β = 5.513; CI95% = 0.706/10.321). In conclusion, special attention should be paid to women with a history of mood disorders and a positive diagnosis of COVID-19 during pregnancy or postpartum, even more so in the case of multiparous women, because of its impact on mental health during the postpartum period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pregnancy and postpartum periods are characterised for being periods in which women experience many changes at social, physiological, and psychological levels (Lutkiewicz et al., 2020), which may lead to the appearance or relapse of mental disorders such as depression and anxiety (Biaggi et al., 2016). These two disorders affect both the mother’s and the new-born’s health and even the relationship between them (Mohammad-Redzuan et al., 2020; Biaggi et al., 2016; Branquinho et al., 2020).

Pursuant to the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2014) postpartum depression (PPD) is the most frequent mental disorder during the puerperium. It is defined as a major depressive episode which may start during pregnancy or during the first four weeks following the postpartum period and which may persist until a year after delivery. It is characterised by sadness, anhedonia, fatigue, low self-esteem, sense of guilt, sleep disorders, decreased appetite, worries about the baby’s health, and suicidal ideation (Missler et al., 2020). On the other hand, postpartum anxiety is characterised by excessive and persistent distress related to disquiet, irritability, nervousness, fear, and sleep disorders. It is connected to PPD, and may lead to a lower possibility of breastfeeding, an increase in the risk of child abuse, new-born’s cognitive and social impairment, and a higher probability of anxiety in the baby (Mohammad-Redzuan et al., 2020).

PPD is present in 10-15% of women, particularly in less developed countries. On the other hand, postpartum anxiety affects between 8% and 13% (Molgora & Accordini, 2020) and the comorbidity of both is approximately 75% (Mohammad-Redzuan et al., 2020).

Although the exact causes remain unknown, multiple factors could influence the onset of PPD and anxiety. On the one hand, biological factors such as hormonal changes after childbirth (Molgora & Accordini, 2020). On the other hand, social and cultural factors, such as a history of child abuse (Biaggi et al., 2016), lack of social/family support during pregnancy and/or postpartum (Yan et al., 2020), poor relationship (Biaggi et al., 2016), not being married (Stepowicz et al., 2020), belonging to a low socioeconomic level (Missler et al., 2020), or being a smoker and using drugs (Spinola et al., 2020). There is also evidence of the influence of obstetric factors, for example, being multiparous (Stojanov et al., 2020), having a negative behaviour towards the pregnancy, or the type of delivery, so that there is a relationship between caesarean delivery and higher levels of PPD and anxiety (Mohammad-Redzuan et al. al., 2020). Finally, psychological factors have also been highlighted, for example, having low self-esteem and being emotionally unstable (Biaggi et al., 2016), a family or personal history of bipolar disorder, anxiety, or depression (Missler et al., 2020; Spinola et al., 2020), and serious illness, bereavement, miscarriage, and previous high-risk pregnancies (Yan et al., 2020). Having these disorders during pregnancy carries obstetric and perinatal health risks for the mother and foetus, such as an increased likelihood of pre-eclampsia, hypertension, and gestational diabetes (Stojanov et al., 2020). It is affirmed that such disorders are related to low scores on the Apgar test, prematurity, congenital disorders, low birthweight, reduction of head circumference, higher probability of suffering from depression, anxiety, attention deficit disorder, and hyperactivity in the future. PPD is also linked to disorders in the cognitive, physical, and linguistic development of children during the first year of life (Do et al., 2018; Lebel et al., 2020).

The pandemic has generated in the population an increase in the levels of fear, depression, anxiety, and stress (Stojanov et al., 2020). The prevalence of symptoms of depression and anxiety during the pandemic in the Spanish population was 18.7% and 21.6%, respectively (González-Sanguino et al., 2020). Several authors conclude that stressful contexts increase the prevalence of mental disorders in women during pregnancy and the postpartum period. In this sense, the global COVID-19 pandemic also seems to have had an impact on higher levels of anxiety and postpartum depression (Stepowicz et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2020; Lebel et al., 2020; Romero-González et al. 2020). Specifically in Spain, it has been quantified that the symptoms of anxiety and depression among pregnant women increased by 59% and 38%, respectively, during confinement (Brik et al., 2021).

Measures implemented by health services to control infection have directly affected the psychological well-being of pregnant women. These measures include spacing obstetric appointments, introducing online medical consultations or online childbirth preparation classes, and even being unaccompanied during labour. Indeed, lack of support during childbirth is one of the variables most frequently associated with the occurrence of PPD (Stojanov et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2020; Bertholdt et al. 2020; Nguyen et al., 2022).

Romero-González et al. (2020) state that fear of contagion, solitude, and stress experimented by pregnant women during the pandemic are risk factors for the development of PPD and anxiety. Likewise, during pregnancy, women are more prone to infections, which makes them a vulnerable group in the case of COVID-19. Such fact, associated with a potential transmission of the virus to the foetus, has generated a higher level of anxiety, depression, and stress in women (Mariño-Narváez et al., 2021). Additionally, García-León et al. (2022) stated that the youngest pregnant Spanish women in the first quarter of pregnancy were the most vulnerable to the effects of stress and concerns about COVID-19. However, the fear of contagion made pregnant women one of the most aware groups and predisposed to get vaccinated, even willing to pay for the vaccine if necessary (Nguyen et al., 2021).

Based on previous research on risk factors for the development of PPD and anxiety, the following hypotheses were established:

-

1)

The risk of suffering PPD and/or anxiety differs between those who gave birth before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

2)

The risk of suffering PPD and/or anxiety differs according to sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, relationship status, religion, level of education and working status.

-

3)

The risk of PPD and/or anxiety differs between women who have help raising their children and those who do not.

-

4)

The risk of PPD and/or anxiety differs between those who have a history of mood disorders and those who do not.

-

5)

The risk of PPD and/or anxiety differs between new and multiparous mothers.

-

6)

The risk of suffering PPD and/or anxiety differs among those who have maintained close contact with or have been infected by COVID-19 and those who do not.

The objectives of this study were to identify the level of anxiety and the risk of postpartum depression during the pandemic, related factors, and predictive factors.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Procedure

Cross-sectional study through an online, voluntary, anonymous, and self-administered questionnaire on women who gave birth at the Regional Hospital of the Autonomous City of Melilla (Spain) between March 2020 and March 2021, and who understood the Spanish language.

Contact with women was possible through the different health centres and lactation associations of the Autonomous City of Melilla, as well as the social media in the city, whereby means of links and QR codes, they could access the questionnaire. From the beginning, they were informed of the objectives of the study and their participation was required, as well as their informed consent. Sampling was non-probabilistic by convenience.

Measurement Tool

To collect the data, a three-block questionnaire was developed: socio-demographic, clinical and pandemic-related characteristics, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), and the Spielberger State-Trait Axiety Inventory. First, socio-demographic, clinical and pandemic-related characteristics were included. Second, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS); and third, the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory were employed.

Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Pandemic-Related Characteristics

Sociodemographic variables have been collected (age, marital status, religion, education level, working status) as well as clinical variables (parity, maternal education course attendance, number of maternal education classes attended, positive COVID-19 diagnosis during pregnancy and the postpartum period, close contact with someone with COVID-19 during pregnancy and the postpartum period, personal mood antecedents). Difficulties found in the follow-up of pregnancy and the postpartum period during the pandemic (not being accompanied to medical consultations; delay in testing; delay in attention; online consultation), and the help received for the care of the new-born, have also been taken into account.

Postnatal Depression

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale was created by Cox, Holden, and Sagovsky in 1987, with the aim of helping primary care health professionals to detect PPD. The split-half reliability of the scale was found to be 0.88, and the standardised a-coefficient 0.87 (Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987). This questionnaire validated in Spanish consists of 10 short questions to know mothers’ mood during the last 7 days. Each question has a score between 0 and 3 using a 4-point Likert scale. Items assessed as reversed are 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10. Total score varies between 0 and 30, 10 being the cut-off value, which indicates risk of suffering from said disorder, 0 to 10 being deemed with no risk, and 10 to 30 being deemed risk of PPD (Krauskopf & Valenzuela, 2020).

Postnatal Anxiety

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory was created by Spielberger, et al. in 1983. It is the self-administered questionnaire mostly employed by Spanish psychologists to assess anxiety. It consists of 40 items, divided into two subscales with 20 items to assess trait anxiety (STAI-R) and 20 items to assess state anxiety (STAI-E) using a 4-point Likert scale running from 4 (rarely or nothing) to 3 (almost always or often) in trait and state anxiety, respectively. Updated by Guillén-Riquelme & Buela-Casal (2011), Cronbach’s alpha reliability was 0.90 for Trait and 0.94 for State Anxiety. Reversed items are considered for STAI-R (21,26,27,30,33,36, and 39) and for STAI-E (1,2,5,8,10,11,15,16,19, and 20). For this study, a simplified version of this questionnaire was utilised, the STAI-E, which assesses the level of anxiety generated by a stressful episode, such as the postpartum period, as used by other authors (Gancedo-García et al., 2017; Navas-Arrebola et al., 2022). Total score fluctuates from 0 to 60, including no anxiety (<20 points), mild anxiety (20-25 points), moderate anxiety (26-32 points) and serious anxiety (33-60 points) (Gancedo-García et al., 2017).

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program, version 22, (IBM, New York, NY, USA, for Windows). After data cleaning and coding, the specific analytical procedures were as follows:

-

(1)

The demographic characteristics of the participants were identified using descriptive statistics for the whole sample, calculating frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables and measures of central tendency (mean and standard deviation) for quantitative variables. To check the normality of the sample, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were used.

-

(2)

Bivariate analyses were conducted for depression and anxiety, the sociodemographic variables (age, level of education, marital status, and working status), other variables (number of children, maternal education, mood antecedents, and having had help during the postpartum period to take care of the new-born) and variables related to the COVID-19 pandemic (COVID-19 diagnosis and close contact with the virus) being deemed the independent variables. The Pearson Correlation Coefficient was applied to calculate the relationships of the total of depression and anxiety risk scales with the age and number of children, and the Student’s T Test was applied for the relationship of the total of scales with the remaining dichotomous variables utilised in the study. Furthermore, the chi-squared test was conducted to associate the classified scores of the depression and anxiety risk scales with the other variables. The statistically significant level was set at p < 0.05.

-

(3)

Two models of multiple linear and forward stepwise regression were designed by introducing every independent variable, calculating the beta, standard error, and confidence intervals values at 95%. Linearity and independence of residuals were verified by means of the Durbin-Watson statistic, determining acceptable independence values inferior to 2.5.

Ethical Considerations

This study follows the good clinical practice, as specified by European Directive 2001/20/CE and Law 14/2007, of July 3, on biomedical research. For the treatment of personal data, the provisions of the Spanish Organic Law 3/2018 of December 5 on Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights were followed. All participants were informed of the objectives of the study and provided their consent to participate by checking a specific box. In addition, the study was authorised by the Regional Hospital management.

Results

Characteristics of the Sample

The total number of births during this period was 921. The questionnaire was answered by 83 women. Finally, 14 questionnaires were excluded because they did not comply with the inclusion criteria, so 69 were analysed. The mean age of participants was 30.94 (SD 5). With respect to marital status, 87% were in a relationship, 66.6% were Christians, 76.8% had a higher level of education, and 82.6% were working (Table 1).

The mean of number of children was 1.86 (SD 0.97). Out of the entire sample, 68.1% had attended maternal education classes, with a mean of classes of 4.03 (SD 4.28) and 63.8% had had help to take care of the new-born during the postpartum period. As regards antecedents of mood disorder, 84.1% stated they had had some at some point in their lives (Table 2).

Regarding variables related to the pandemic, 78.3% of women had not been diagnosed with COVID-19 and 52.2% had not had a close contact with a person diagnosed with it. As regards the difficulty for the follow-up of pregnancy by the Health Centre during the pandemic, 92.8% of women represented that they had had some difficulty; the most frequently stated one was the fact of not being accompanied to follow-up consultations during pregnancy (Table 3).

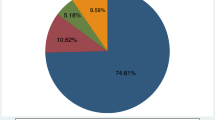

The mean value according to the Edinburgh scale was 16.14 ± 6.54; 85.5% showed risk of depression. While the postpartum anxiety mean was 26.91 ± 12.32, 40.6% of women showed serious anxiety (Table 4).

Bivariate Analysis of Levels of Anxiety and Postpartum Depression

The number of children variable is significantly associated with anxiety, multipara women showing higher levels of anxiety. Having been diagnosed with COVID-19, having had close contact with someone with COVID-19, and having had no help during the postpartum period are closely related to higher levels of anxiety, while having antecedents of mood disorder was related to higher levels of postpartum anxiety and depression (Table 5).

Multiple linear regression model

Table 6 shows the final linear regression model for postpartum depression with the two predictor variables that explained the 36.9% of variability. Women who had had mood antecedents before pregnancy and who were diagnosed with COVID-19 during pregnancy or the postpartum period show a higher score in the postpartum depression risk scale.

Table 7 shows the final linear regression model for postpartum anxiety with the three predictor variables that explained the 46.6% of variability. Women who had had mood antecedents before pregnancy, who were diagnosed with COVID-19 during pregnancy/the postpartum period and who have more than one child show a higher anxiety level during the postpartum period.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify the anxiety level and the postpartum depression risk during the pandemic, related factors, and predictive factors. This study contributes significant data on the influence of COVID-19 on the development of anxiety and postpartum depression risk.

Previous studies conducted before the pandemic reported a mean prevalence of postpartum anxiety of 18.1 ± 7.4, mild anxiety predominating (Gancedo-García et al., 2017). Our results, however, show a higher prevalence of postpartum anxiety during the last year due to the pandemic, with a mean of 26.91 ± 12.32, severe anxiety being the most predominant. The results obtained on the risk of PPD in our sample were an average of 16.14 ± 6.54, while studies carried out before the pandemic (Míguez et al., 2017), informed mean values of 8.16. This data shows that the risk of PPD has increased in the pandemic period. Both results confirm our first hypothesis, which posited that the risk of PPD and/or anxiety differs between those who gave birth before and after the COVID-19 pandemic and confirm that the risk is higher in both cases.

The increase in anxiety and depression risk levels during the pandemic may be due to the several measures taken by the government to reduce the propagation of the disease, including social isolation, which have had a negative impact on the mental health of the population from multiple countries, in general (Le et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021), and on puerperal women, in particular (Galea, Comerciante & Lurie, 2020; Brisk et al., 2021). Additionally, the study conducted by Wang, et al. (2021) found that the Spanish population reported higher levels of stress and depression, as well as more symptoms and use of medical services than participants from China.

Our study wanted to analyse other factors that may influence anxiety disorders and PPD, as established in the initial hypotheses. In accordance with the second hypothesis, the sociodemographic variables such as age, marital status, level of education, working status, and maternal education were not significantly related to the appearance of postpartum anxiety and depression in our sample, as stated by Pham et al. (2017) before the pandemic. Nevertheless, such result differs from other studies, which consider that being younger than 30 and single are PPD risk factors (Cordova, 2017; Meléndez et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020). While as regards the level of education, several authors disagree with our results by stating that having primary education or being an illiterate person is related to the risk of PPD appearance (Cordova, 2017; Míguez et al., 2017; Pham et al., 2017); in contrast, Yan et al’s study (2020) noted that it was related to the mothers’ high level of education.

Although our results did not show an association between working status and these pathologies, many authors represented that unemployed mothers had higher PPD risk (Míguez et al., 2017; Pham et al., 2017; Romero et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2020). Likewise, having a low socioeconomic level is deemed a risk factor for such disorder (McCartney, 2019). These variables in our study may have been not significant due to the participants’ profile, most of our sample was older than 30, were in a relationship, had a higher level of education, and were employed.

With regard to the third hypothesis (the risk of PPD and/or anxiety differs between women who have help raising their children and those who do not), our study shows an increase in cases of postpartum anxiety and depression risk in women who had no help to take care of the new-born. Therefore, our results confirm this hypothesis and are in accordance with previous research (Brisk et al., 2021; Berthold et al., 2020; Fallon et al., 2021; Pham et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2020). In our results, limitation on health attendance has had no impact on the increase in cases of such pathologies; however, Davenport et al. (2020) discovered a relationship between health restrictions and an increase in psychological issues; this may be due to the fact that the women of our study accepted the health attention restrictions imposed due to the pandemic.

In response to hypothesis four (the risk of PPD and/or anxiety differs between those who have a history of mood disorders and those who do not), when adjusted to the rest of variables, having mood antecedents maintained an association with postpartum anxiety and depression risk. Hence, this result confirms the hypothesis and coincides with other studies performed before the pandemic (Gancedo-García et al., 2017; Míguez et al., 2017; Pham et al., 2017; Spinola et al., 2020; Brisk et al., 2021). It can be stated that this variable could be considered a risk factor present both in non-pandemic and pandemic contexts.

Regarding hypothesis five (the risk of PPD and/or anxiety differs between new and multiparous mothers), our results show that the number of children was also significantly related to both pathologies. Multipara women reported more postpartum anxiety and risk of depression. These results confirm this hypothesis and are in line with other authors (Romero et al., 2017; Bertholdt et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2020). This is justified on the basis that taking care of a new-born is a great psychological burden that alters the mother’s mental health, such disorder being higher during the pandemic as a consequence of the social isolation they had to face and not being able to receive any help with the baby from their relatives and/or acquaintances, in addition to taking care of the other children not attending school or doing so within reduced hours.

When considering COVID-related variables, those who had close contact with the disease and/or a positive diagnosis during pregnancy or the postpartum period showed more anxiety and risk of PPD. This finding coincides with the results of Wu et al.’s (2020) and Missler et al.’s studies (2020). This may be due to the fear pregnant women felt about the lack of knowledge on the vertical transmission to the foetus (Romero-González et al., 2020; Spinola et al.,2020). These results confirm our last hypothesis, the risk of suffering PPD and/or anxiety differs among those who have maintained close contact with or have been infected by COVID-19.

Online psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or mindfulness based cognitive therapy (MBCT) could have been useful in relieving stress and reducing postpartum anxiety (Ho, Chee & Ho, 2020; Soh et al., 2020; Zhang & Ho, 2017). In addition, accurate dissemination of health information and follow-up during pregnancy and postpartum by telephone or online would reduce depression during this period.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the sample size is small, so that the results are not extrapolated. Second, during the pandemic the birth rate in the city decreased due to mobility reasons derived from the geographical characteristics of Melilla, an isolated border city. In addition, access to Health Centres to recruit women was restricted. In order to reduce this limitation, successive calls were made at different times. Finally, this study was not randomised, therefore it is possible that respondents were the most motivated women with more knowledge of such variables; nonetheless, given the pandemic context and the limited access to women, a randomised sample was not a choice.

Conclusion

Almost half of the women of our study who gave birth during the pandemic showed serious anxiety. This was higher in multiparous women, who had had close contact with the disease, who had been diagnosed with COVID-19, with antecedents of mood disorder, and who had no help during the postpartum period to take care of the new-born. Most of the sample showed high levels of PPD risk during such period. Depression risk was higher in puerperal women who had had close contact with COVID-19 patients, who had been diagnosed with it, who had mood antecedents and who had no help to take care of the baby. Mood antecedents and a positive COVID-19 diagnosis during pregnancy or the postpartum period predicted an increase in the risk of postpartum depression; while for postpartum anxiety, the predictive factor of being multipara must be added to mood antecedents and being diagnosed with COVID-19.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2014). Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales (DSM-5), 5ª Ed. Editorial Médica Panamericana.

Biaggi, A., Conroy, S., Pawlby, S., & Pariante, C. (2016). Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 191, 62–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.014

Branquinho, A., Canavarro, M., & Fonseca, A. (2020). A blended cognitive-behavioral intervention for the treatment of postpartum depression: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228631

Brik, M., Sandonis, M. A., Fernández, S., Suy, A., Parramon-Puig, G., Maiz, N., et al. (2021). Impacto psicológico y apoyo social en mujeres embarazadas durante el confinamiento por la pandemia de SARS-CoV2: un estudio de cohortes. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 100(6), 1026–1033. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.14073

Cordova, J. F. (2017). Factores asociados a depresión postparto en puérperas atendidas en Hospital II-2 Santa Rosa Durante Septiembre-Diciembre,2017. Thesis, University of Piura.

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

Fallon, V., Davies, S. M., Silverio, S. A., Jackson, L., De Pascalis, L., & Harrold, J. A. (2021). Psychosocial experiences of postnatal women during the COVID-19 pandemic. A UK-wide study of prevalence rates and risk factors for clinically relevant depression and anxiety. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.048

Galea, S., Merchant, R. M., & Lurie, N. (2020). The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(6), 817–818. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562

Gancedo-García, A., Fuente-Gónzalez, P., Chudacik, M., Fernández-Fernández, A., Suárez-Gil, P., & Suárez Martínez, V. (2017). Factors associated with the anxiety level and knowledge about childcare and lactation in first-time pregnant women. Atencion Primaria, 51(5), 285–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aprim.2017.12.005

González-Sanguino, C., Ausín, B., Castellanos, M. Á., Saiz, J., López-Gómez, A., Ugidos, C., & Muñoz, M. (2020). Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 172–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040

Ho, C. S., Chee, C. Y., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 49(1), 1–3.

Krauskopf, V., & Valenzuela, P. (2020). Perinatal depression: A review on diagnosis and treatment strategies. Revista médica clínica las condes, 31(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmclc.2020.01.004

Le, X. T. T., Dang, A. K., Toweh, J., Nguyen, Q. N., Le, H. T., Do, T. T. T., et al. (2020). Evaluating the psychological impacts related to COVID-19 of Vietnamese people under the first nationwide partial lockdown in Vietnam. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-021-00237-7

Lebel, C., MacKinnon, A., Bagshawe, M., Tomfohr-Madsen, L., & Giesbrecht, G. (2020). Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.126

Lutkiewicz, K., Bieleninik, L., Ciéslak, M., & Bidzan, M. (2020). Maternal-infant bonding and its relationships with maternal depressive symptoms, stress and anxiety in the early postpartum period in a polish sample. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155427

Mariño-Narvaez, C., Puertas-Gonzalez, J. A., Romero-Gonzalez, B., & Peralta-Ramirez, M. I. (2021). Giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic: The impact on birth satisfaction and postpartum depression. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 153(1), 83–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13565

Meléndez, M., Díaz, M., Bohorjas, L., Cabaña, A., Casas, J., Castrillo, M., & Corbino, J. (2017). Depresión postparto y los factores de riesgo. Salus, 21(3), 7–12 http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=375955679003

Míguez, M. C., Fernández, V., & Pereira, B. (2017). Depresión postparto y factores asociados en mujeres con embarazos de riesgo. Psicología Conductual, 25(1), 47–64.

Nguyen, L. H., Hoang, M. T., Nguyen, L. D., Ninh, L. T., Nguyen, H. T. T., Nguyen, A. D., et al. (2021). Acceptance and willingness to pay for COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant women in Vietnam. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 26(10), 1303–1313. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13666

Nguyen, L. H., Nguyen, L. D., Ninh, L. T., Nguyen, H. T. T., Nguyen, A. D., Dam, V. A. T., et al. (2022). COVID-19 and delayed antenatal care impaired pregnant women's quality of life and psychological well-being: What supports should be provided? Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Affective Disorders, 298, 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.102

Pham, D., Cormick, G., Amyx, M. M., Gibbons, L., Doty, M., Brown, A., Norwood, A., Daray, F., Althabe, F., & Belizán, J. M. (2017). Factors associated with postpartum depression in women from low socioeconomic level in Argentina: A hierarchical model approach. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.091

Romero, D., Orozco, L. A., Ybarra, J. L., & y Gracia, B.I. (2017). Sintomatología depresiva en el postparto y factores psicosociales asociados. Revista Chilena de Obstetricia y Ginecología, 82(2), 152–162. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-75262017000200009

Soh, H. L., Ho, R. C., Ho, C. S., & Tam, W. W. (2020). Efficacy of digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Medicine, 75, 315–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.08.020

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, T. E., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press.

Stepowicz, A., Wencka, B., Bienkiewicz, J., Horzelski, W., & Grzesiak, M. (2020). Stress and anxiety levels in pregnant and post-partum women during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249450

Wang, C., Chudzicka-Czupała, A., Grabowski, D., Pan, R., Adamus, K., Wan, X., et al. (2020). The association between physical and mental health and face mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparison of two countries with different views and practices. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 569981. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569981

Wang, C., López-Núñez, M. I., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., et al. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health in China and Spain: Cross-sectional study. JMIR formative research, 5(5), e27818. https://doi.org/10.2196/27818

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729

Wang, C., Tripp, C., Sears, S. F., Xu, L., Tan, Y., Zhou, D., et al. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health in the two largest economies in the world: A comparison between the United States and China. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 44(6), 741–759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-021-00237-7

Zhang, M. W., & Ho, R. (2017). Moodle: The cost effective solution for internet cognitive behavioral therapy (I-CBT) interventions. Technology and Health Care, 25(1), 163–165. https://doi.org/10.3233/THC-161261

Bertholdt, C., Epstein, J., Banasiak, C., Ligier, F., Dahlhoff, S., Olieric, M., Mottet, N., Beaumont, M., & Morel, O. (2020). Birth experience during COVID-19 confinement (CONFINE): Protocol for a multicentre prospective study. BMJ Open, 10(12). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043057

Davenport, M. H., Meyer, S., Meah, V. L., Strynadka, M. C., & Khurana, R. (2020). Moms are not OK: COVID-19 and maternal mental health. Frontiers in global Women’s Health, 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2020.00001

Do, T., Nguyen, T., & Pham, T. (2018). Postpartum depression and risk factors among Vietnamese women. BioMed Research International. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4028913

Garcia-Leon, M. A., Martin-Tortosa, P. L., Cambio-Ledesma, A., & Caparros-Gonzalez, R. A. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic and psychopathological symptoms in pregnant women in Spain. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2022.2047623

Guillén-Riquelmeé, A., & Buela-Casal, G. (2011). Actualizacion psicometrica y funcionamiento diferencial de los items en el State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Psicothema.

McCartney, K. (2019). Parenting in the age of information overload. Smith Alumnae Quarterly. https://www.smith.edu/president-kathleen-mccartney/speeches/saq-fall-2019

Missler, M., Van Straten, A., Denissen, J., Donker, T., & Beijers, R. (2020). Effectiveness of a psycho-educational intervention for expecting parents to prevent postpartum parenting stress, depression and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03341-9

Mohammad-Redzuan, S., Suntharalingam, P., Palaniyappan, T., Ganasan, V., Megat-Abu-Bakar, P., Kaur, P., Marmuji, L., Ambigapatía, S., Paranthaman, V., & Masticar, B. (2020). Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression, general depressive symptoms, anxiety and stress (PODSAS) among mothers during their 4-week postnatal follow-up in five public health clinics in Perak: A study protocol for a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 10(6). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034458

Molgora, S., & Accordini, M. (2020). Motherhood in the time of coronavirus: The impact of the pandemic emergency on expectant and postpartum Women’s psychological well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567155

Navas-Arrebola, R. N., Peteiro-Mahia, L., Blanco-López, S., López-Castineira, N., Seoane-Pillado, T., & Pertega-Diaz, S. (2022). Women's satisfaction with childbirth and postpartum care and associated variables. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 55. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1980-220X2020006603720

Romero-Gonzalez, B., Puertas-Gonzalez, J., Mariño-Narvaez, C., & Peralta-Ramirez, M. (2020). Confinement variables by COVID-19 predictors of anxious and depressive symptoms in pregnant women. Medicina Clínica. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2020.10.002

Spinola, O., Liotti, M., Speranza, A., & Tambelli, R. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 epidemic lockdown on postpartum depressive symptoms in a sample of Italian Mothers.Frontiers. Psychiatry, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589916

Stojanov, J., Stankovic, M., Zikic, O., Stankovic, M., & Stojanov, A. (2020). The risk for nonpsychotic postpartum mood and anxiety disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Psychiatric in Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217420981533

Wu, Y. P., Zhang, C., Liu, H., Duan, C., Li, C., Fan, J., Li, H., Chen, L., Xu, H., Li, X., Guo, Y., Wang, Y., Li, X., Li, J., Zhang, T., You, Y., Li, H., Yang, S., Tao, X., et al. (2020). Perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms of pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 223(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.009

Yan, H., Ding, Y., & Guo, W. (2020). Mental health of pregnant and postpartum women during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.617001

Funding

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad de Granada/CBUA The study was not funded; no researcher received grants, salary, or reimbursements for the realisation of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval Statement

This study follows the good clinical practice, as specified by European Directive 2001/20/CE and Law 14/2007, of July 3, on biomedical research. For the treatment of personal data, the provisions of the Spanish Organic Law 3/2018 of December 5 on Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights were followed.

Informed Consent

All participants were informed of the objectives of the study and provided their consent to participate by checking a specific box on the questionnaire.

In addition, the study was authorised by the Regional Hospital management.

Conflict of Interest

- All the authors of the article declare that it is an original article, that it has not been previously published or is under review in any journal.

- All authors have reviewed and accepted the manuscript. And they have contributed to its elaboration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

STROBE Statement—checklist of items that should be included in reports of observational studies (DOCX 28 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Remartínez-Hamed, A., Pérez-Morente, M.Á., Álvarez-Serrano, M.A. et al. Levels and predictors of postpartum depression and anxiety during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in a confined cross-border city. Curr Psychol 43, 5291–5300 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04719-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04719-6