Abstract

Early maladaptive schemas (EMS), illness representations, and coping are associated with clinical outcomes of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD). However, the pathways that link these factors are largely unknown. The present prospective study aimed at investigating the possible mediating role of illness representations and coping in the associations among schema domains, symptom severity, and suicide risk in MDD. Participants were 135 patients diagnosed with MDD, aged 48.13 ± 14.12 (84.4% females). The Young Schema Questionnaire-Short Form 3 was used to measure schema domains at baseline. Illness representations and coping were measured at approximately five months later (mean = 5.04 ± 1.16 months) with the Illness Perception Questionnaire-Mental Health and the Brief COPE Inventory, respectively. MDD outcomes were measured about 10 months after the baseline assessment (mean = 9.44 ± 2.36 months) with the Beck Depression Inventory and the Risk Assessment Suicidality Scale. SPSS AMOS 27 was used to conduct path analysis. Serial mediation Structural Equation Modelling, controlling for age, education, marital status, working status, MDD duration, pharmacotherapy, and psychotherapy, revealed that Impaired Autonomy and Performance was positively linked to suicide risk. Negative MDD impact representations and symptom severity serially mediated the aforementioned association. Finally, problem-focused coping was negatively related to symptom severity and suicide risk. This study’s main limitation was modest sample size. Representations regarding the impact and severity of MDD mediate the effects of Impaired Autonomy and Performance on future suicide risk in MDD. Healing Impaired Autonomy and Performance domain of EMS, restructuring patients’ representations of high MDD impact, and enhancing problem-focused coping could significantly reduce symptom severity and suicide risk in Schema Therapy with MDD individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common mental disorder affecting more than 290 million people worldwide (Ferrari et al., 2013). According to cognitive theories of psychopathology, maladaptive cognitions play a key role in the emergence and course of MDD by placing individuals at risk for developing depressive symptoms, particularly when they are under high stress, and by maintaining the depressive symptomatology (Abramson et al., 1989; Beck & Haigh, 2014; Reilly et al., 2012). Moreover, according to Strauman and Eddington (2017), MDD can be conceptualized as a disorder of self-regulation, and maladaptive cognitions play an essential role in patients’ self-regulation processes.

Early maladaptive schema domains

Early Maladaptive Schemas (EMS) are broad pervasive patterns comprising memories, cognitions, emotions, and physical sensations (Young, 1999). EMS emerge during childhood and adolescence in response to the frustration of early core emotional needs and collude with temperamental factors to contribute to psychopathological manifestations. Currently, 18 EMS have been identified and grouped into the following five broad categories called schema domains: Disconnection and Rejection, Impaired Autonomy and Performance, Impaired Limits, Other-Directedness, and Overvigilance and Inhibition (Young et al., 2003). Moreover, in their recent work, Bach et al. (2018) identified four higher-order schema domains instead of the original five: Disconnection & Rejection, Impaired Autonomy & Performance, Excessive Responsibility & Standards, and Impaired Limits.

Lately, there has been an increasing amount of research concerning the role of EMS in MDD. According to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Bishop et al. (2021), all EMS are positively associated with the severity of depressive symptoms in patients with MDD, in patients with other mental disorders such as bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and body dysmorphic disorder, and in the general population. Moreover, patients with MDD report significantly higher maladaptive EMS than the general population (Halvorsen et al., 2009) and, in some cases, higher than patients with other severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia (Jang & Lee, 2020). In addition, EMS in MDD present stability over time (Halvorsen et al., 2010; Renner et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2010), thus making them potentially crucial long-term vulnerability factors.

Illness representations and coping

According to the leading model of illness-related self-regulation, the Common-Sense Model (CSM; Leventhal et al., 1980, 2003), there are two main processes which play a crucial role in how patients adapt to their diagnosis: illness representations and coping. The CSM was originally used to describe patients’ self-regulation processes in physical illnesses, such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and diabetes (see meta-analyses by Dempster et al., 2015; Hagger et al., 2017). The model was later used successfully with patients with mental disorders, such as schizophrenia spectrum disorders and bipolar disorder (for a meta-analysis, see Cannon et al., 2022), and MDD (for a systematic review, see Mavroeides & Koutra, 2021).

Illness representations are a particular type of illness-related cognitions organizing patients’ beliefs about their diagnosis (Leventhal et al., 1980, 2003). The CSM proposes that patients form cognitive and emotional representations of their illness to deal with it. Cognitive illness representations consist of patients’ beliefs about the identity of the disease, namely its label and symptoms, the disease’s causes, time frame (acute, chronic, cyclical), consequences on patients’ lives, and the potential for personal and treatment control. Emotional representations are patients’ emotions in response to the illness. Patients’ illness representations determine their self-management by guiding the strategies they utilize to cope with the illness, thus affecting clinical outcomes (Leventhal et al., 1980, 2003).

In MDD, illness representations are linked to various clinical and treatment-related outcomes. According to a recent systematic review by Mavroeides and Koutra (2021), illness representations are associated with the severity of depressive symptoms, patients’ anxiety and perceived stress levels, psychosocial functioning, comorbidity, medication adherence, and the duration of pharmacotherapy. Moreover, illness representations are linked to prominent MDD phenomena, such as rumination (Lu et al., 2014) and self-blaming (Brown et al., 2007).

The CSM identifies coping as the second critical illness-related self-regulation process that plays a role in adaptation to an illness and determines its course and outcome (Leventhal et al., 1980, 2003). Coping refers to people’s cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage stress, and based on its function, it can be divided into problem-focused and emotion-focused (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Problem-focused coping consists of efforts to resolve the stressful situation or alter the source of stress, while emotion-focused coping aims at managing one’s emotions that are linked to the stressful situation (Carroll, 2013). Carver et al. (1989) specified a third group of coping strategies, the less useful or maladaptive coping, corresponding to less beneficial strategies such as behavioral disengagement and emotion venting. According to the meta-analysis by Hagger et al. (2017), the CSM does not specify particular coping procedures, but previous distinctions, such as those of Lazarus and Folkman (1984) and Carver et al. (1989), are commonly employed.

The role of coping in MDD is well-established. Specifically, individuals with MDD are more often engaged in maladaptive coping (e.g., denial) than adaptive coping (e.g., active coping) (Orzechowska et al., 2013). Moreover, specific coping mechanisms have been linked to MDD outcomes, such as patient quality of life (Holubova et al., 2018), suicidal ideation (De Berardis et al., 2020), efficacy of psychotherapy for MDD (Renaud et al., 2014), and symptom remission (Rodgers et al., 2017).

The interplay between EMS, illness representations, and coping

Illness representations are linked to coping in patients with MDD. Specifically, current research links positive illness representations (e.g., high perceived control over the illness) to more adaptive ways of coping in MDD patients and negative illness representations (e.g., more perceived illness consequences) to more maladaptive coping (Brown et al., 2001; Kelly et al., 2007; Mavroeides & Koutra, 2022). Moreover, according to Brown et al. (2007), various coping strategies mediate or moderate the association between illness representations and psychosocial functioning in MDD patients.

Research on EMS in association with self-regulation processes is scarce. Studies employing non-clinical samples suggest that specific EMS, such as Vulnerability to Harm or Illness, Punitiveness, and Unrelenting Standards (Babajani et al., 2014), and Disconnection and Rejection, and Impaired Autonomy domains (Ke & Barlas, 2020) are associated with coping in the general population. Moreover, according to the findings of a recent study by Mc Donnell et al. (2018), EMS are associated with coping in poly-drug users.

The present study

To our knowledge, no empirical investigation has examined whether EMS domains are associated with MDD patients’ illness representations and coping strategies and whether illness representations and coping mediate the effect of schema domains on MDD outcomes. This topic is critical toward elucidating the degree to which patients’ schemas are linked to MDD outcomes through patients’ self-regulation skills. Identifying modifiable factors contributing to the severity of depression symptoms has become a national emergency given the high frequency of MDD in Greece over a decade-long economic recession (Basta et al., 2021, 2022; Economou et al., 2013, 2016; Madianos et al., 2011). However, currently no data exist about Greek MDD patients’ EMS and the only available data about illness-related self-regulation and its role in MDD outcomes are preliminary and come from validating an illness representations measure (Mavroeides & Koutra, 2022). Given that illness-related self-regulation processes and their associations with mental health are largely culturally-determined (Antoniades et al., 2017; Reichardt et al., 2018; Sinha & Watson, 2007), increasing knowledge about Greek MDD patients’ illness representations, coping, and how they are related to MDD outcomes is critical.

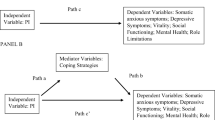

Hence, the current prospective study aimed to investigate the impact of EMS and self-regulation processes, indexed by illness representations and coping, on two major MDD outcomes (symptom severity and suicidality). We hypothesized (a) that schema domains are associated with higher MDD suicide risk and (b) that illness representations, and symptom severity serially mediate the aforementioned association. More specifically, we hypothesized that EMS domains are associated with high MDD impact representations (i.e., identity, consequences, chronicity, cyclicality, and emotional representations) leading to more maladaptive and emotion-focused coping, thus resulting to increased symptom severity and suicide risk. Furthermore, EMS domains are related to low control and coherence representations leading to less problem-focused coping, thus resulting to increased symptom severity and suicide risk. Figure 1 schematically illustrates the hypothesized, conceptual model.

Methods

Participants

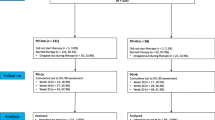

As recommended by MacCallum et al. (1996), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was used to calculate the required sample size and the achieved power for our model. The required sample size was N = 105 for 42 degrees of freedom, a p < 0.05, desired power of 0.80, RMSEA = 0 for the null hypothesis and RMSEA = 0.08 for the alternative hypothesis. Achieved power based on our final sample size was 0.92. A total of 234 patients with a clinical diagnosis of MDD were contacted and informed about the purpose of the present study between May 2019 and November 2020. Participants were recruited from the outpatient department and the mobile mental health unit (MMHU) of the Psychiatric Clinic of the University General Hospital of Heraklion in Crete, Greece, and from an online depression peer support group. Diagnosis of MDD was assessed by experienced attending psychiatrists of the University General Hospital of Heraklion using standard procedures (clinical evaluation including the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview) based on the DSM-5 criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Sheehan et al., 1998). Participants recruited through the online peer support group had received a formal diagnosis of MDD by a psychiatrist. In Heraklion, 129 patients were contacted during their visit to the outpatient department, and 88 were contacted during their visit to the MMHU. Seventeen patients were contacted through the online peer support group. Finally, 216 patients (response rate = 92.3%) agreed to participate in the study and returned usable data during the baseline assessment (T1) (n = 117 from the outpatient department, n = 82 from the MMHU, and n = 17 from online peer support). One hundred fifty patients (attrition rate: 31.6%) returned usable data during the study’s second wave (T2) (n = 80 from the outpatient department, n = 60 from the MMHU, and n = 10 from online peer support). Finally, 135 patients (attrition rate from T1: 37.5% and from T2: 10%) returned usable data during the study’s third wave (T3) (n = 72 from the outpatient department, n = 54 from the MMHU, and n = 9 from online peer support) (Fig. 2).

The criteria for inclusion in the study were: i) being diagnosed by a psychiatrist with MDD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) or the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10), ii) having a good understanding of the Greek language, and iii) aged 18 or older. Participants were excluded if they were diagnosed with severe mental disorders other than MDD, substance use disorder, neurological or severe physical illness, or intellectual disability.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Crete (registration number: 44/18.03.2019). Following the presentation of the study’s aims and methods, all participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study, according to the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013).

Measures

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, educational level, marital status, working status) and clinical characteristics (e.g., illness duration, hospitalizations, pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy) were collected through a structured questionnaire.

Young Schema Questionnaire-Short Form

The Young Schema Questionnaire-Short Form 3 (YSQ-S3; Young, 2005) is a 90-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure the 18 EMS and the five broad schema domains described by Young et al. (2003). The five domains measured by the YSQ-S3 are Disconnection and Rejection, Impaired Autonomy and Performance, Impaired Limits, Other-Directedness, and Overvigilance and Inhibition. The Disconnection and Rejection domain comprises the Abandonment/ Instability, Mistrust/ Abuse, Emotional Deprivation, Defectiveness/ Shame, and Social Isolation/ Alienation EMS. Impaired Autonomy and Performance includes the Dependence/ Incompetence, Vulnerability to Harm or Illness, Enmeshment/ Undeveloped Self, and Failure to Achieve EMS. Impaired Limits comprise the Entitlement/ Grandiosity and Insufficient Self-Control/ Self-Discipline EMS. Other-Directedness domain refers to the Subjugation, Self-Sacrifice, and Approval-Seeking/ Recognition-Seeking EMS. Finally, Overvigilance and Inhibition domain includes the Negativity/ Pessimism, Emotional Inhibition, Unrelenting Standards/ Hypercriticalness, and Punitiveness EMS. Responses to the YSQ-S3 are made on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1=“Completely untrue for me” to 6=“Describes me perfectly.” Since mean scores were used in this study, the possible range for all schema domains subscales was 1-6. The YSQ-S3 has been validated for use in the Greek population (Malogiannis et al., 2018). Cronbach’s alpha values for the five domains in this study were: .94 for Disconnection and Rejection, .90 for Impaired Autonomy and Performance, .75 for Impaired Limits, .84 for Other-Directedness, and .89 for Overvigilance and Inhibition.

Illness Perception Questionnaire- Mental Health

The Illness Perception Questionnaire- Mental Health (IPQ-MH; Witteman et al., 2011) is a 67-item self-report assessing various illness representations dimensions of patients with mental disorders. Responses to the IPQ-MH are made on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1=“Not at all/ Strongly disagree” to 5=“Very much/ Strongly agree.” The IPQ-MH has been validated in the Greek population (Mavroeides & Koutra, 2022) and measures 13 distinct illness representation dimensions. To reduce analyses’ complexity, we combined illness representations’ dimensions into broader illness schemas. This is in line with theory since illness representations are parts of broader health schemas, according to Leventhal et al. (1980). Moreover, Skinner et al. (2011) argue that combining illness representations can be more helpful in understanding patterns of responding to an illness than investigating illness representations dimensions separately. Hence, in this study, we combined identity (felt symptoms), consequences, chronic timeline, cyclical, and emotional representations into representations about the impact of MDD (possible range 28-140), and coherence, personal control, and treatment control into representations of control over MDD (possible range 13-65). Cronbach’s alpha values in this study for impact and control representations were .95 and .86, respectively.

Brief Cope Orientation to Problems Experienced

The Brief Cope Orientation to Problems Experienced (Brief COPE; Carver, 1997) is a 28-item self-report questionnaire assessing 14 strategies for coping with stress. Respondents answer each item on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1=“I haven’t been doing this at all” to 4=“I’ve been doing this a lot.” The Brief COPE has been validated for use in the Greek population (Kapsou et al., 2010). In line with various previous studies (Cooper et al., 2008; Kalaitzaki, 2021), in this study, we combined active coping, use of informational support, and planning into problem-focused coping (possible range 3-12), acceptance, use of emotional support, humor, positive reframing, and religious coping into emotion-focused coping (possible range 5-20), and behavioral disengagement, denial, self-distraction, self-blame, substance use, and venting into dysfunctional/ maladaptive coping (possible range 6-24). Cronbach’s alpha values in the present study were: .77 for problem-focused, .63 for emotion-focused coping, and .67 for maladaptive coping.

Beck Depression Inventory

Severity of MDD symptoms, indexed by the total score on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) served as one of the two major study outcomes. The BDI is a 21-item multiple-choice self-report questionnaire assessing symptoms such as low mood, suicidal ideas, and fatigability experienced during the past week (Beck et al., 1961). Responses to the BDI are made on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3 (possible range 0-63). The BDI has been validated for use in the Greek population (Jemos, 1984). Cronbach’s alpha value was .92 in the current study.

Risk Assessment Suicidality Scale

Suicidality risk assessed using the total score on the Risk Assessment Suicidality Scale (RASS; Fountoulakis et al., 2012) served as the second study outcome. The RASS is a 12-item self-report questionnaire originally developed for the Greek population to measure suicide-related behavior and inner experience. Responses to the RASS items are made on a 4-point Likert–type scale ranging from 0=“Not at all” to 3 = “Very much”, with total scores ranging between 0 and 1190, and Cronbach’s a = .85.

Procedure

In the current study, we utilized T1 data regarding patients’ sociodemographic characteristics and schema domains, T2 data regarding patients’ representations of MDD and coping styles, and T3 data regarding MDD symptom severity and suicide risk. The initial assessment took place in person during a scheduled appointment with the patients, with a mean duration of 90 minutes. During the initial assessment, patients were informed about T2 and T3, and those who agreed to participate in them provided a phone number or an email address to the researchers to contact them. The average time interval between T1 and T2 was 5.04 months (SD = 1.16; range 3-7 months), and the average time interval between T2 and T3 was 4.43 months (SD = 1.44; range 3-7 months).

The package of questionnaires for T1 assessment was administered to patients by the first author in individual sessions at the Psychiatric Clinic or the MMHU of the University Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, Greece. The questionnaires were also administered online to patients with MDD recruited from an online peer support group who completed them individually. In this case, after receiving approval from the website’s administrator, we made an announcement about the study on the group’s website and posted a link to a Google Form containing the questionnaires. Patients interested in the study could follow the link and participate in the survey online. Participants were given an information sheet describing the aims of the study. After answering T1 questionnaires, patients who consented to participate in T2 and T3 assessments provided an email address to the researchers to contact them. T2 and T3 data were also collected using Google Forms. If needed, participants could ask a specially trained graduate-level psychologist (the first author) for help.

Data analysis

Homoscedasticity was checked by plotting the predicted values against residuals. Linearity was tested using P-P plots. Normality was assessed using skewness and kurtosis values, and multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance with a cutoff value of 5 and .20, respectively (James et al., 2013; Menard, 1995). Mahalonobis distance was used to test for outliers at p < .001 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). To test for differences between patients who participated in T2 and T3 and those who did not participate in them, as well as between patients from peer support and hospital-based patients, we used the t-test for independent samples for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables. To test for possible control variables, a series of MANOVAs were performed. In each MANOVA, schema domains, illness representations, coping, and MDD outcomes were used as the dependent variables. Gender (male, female), marital status (married, non-married, widowed/divorced), educational level (elementary school, junior high school, high school, vocational training, university degree), working status (working, not working), duration of MDD (<6 months, 6-12 months, 1-2 years, 3-4 years, >5 years), pharmacotherapy (no, yes), psychotherapy (no, yes), and hospitalization (no, yes) were used separately as independent variables. The correlations of schema domains, illness representations, coping, MDD outcomes, and age were also examined using Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient. The aforementioned analyses were conducted assuming a 0.05 significance level.

To investigate the indirect effects of schema domains on suicide risk through illness representations, coping, and MDD severity we used Structural Equation Modelling. A complete mediation model (Model 1) was tested by assuming only indirect effects between schema domains and suicide risk. A partial mediation model (Model 2) alternative to Model 1 was also tested by specifying direct effects between schema domains and suicide risk outcomes in addition to the indirect ones. Bootstrapping with 2000 resamples and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was used. Bootstrapping has been shown to control for Type I error by reducing false discovery rates up to 80% in comparison to analyses conducted without bootstrapping (Meuwissen & Goddard, 2004). Moreover, bootstrapping adequately accounts for Type I error even for complex SEM models with multiple mediations (Cheung & Lau, 2007; Williams & MacKinnon, 2008). To assess model fit, we used a series of absolute (Chi-square [χ2], Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual [SRMR]), relative (Normed Fit Index [NFI], Tucker-Lewis Index [TLI], Incremental Fit Index [IFI]), and centrality-based fit indices (Comparative Fit Index [CFI], RMSEA). Cutoff values were: NFI ≥0.90 (Byrne, 2010; Hair et al., 1998), TLI, IFI, and CFI ≥0.90 for acceptable fit and ≥ 0.95 for excellent fit, RMSEA ≤0.06, SRMR ≤0.08, and p for χ2 ≥ 0.05 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 27 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and AMOS 27. Estimated associations are described in terms of β-coefficients (beta) and corresponding 95% CIs.

Results

Sample characteristics

Participants’ socio-demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. The final sample comprised 135 patients, of whom 21 were males (15.6%) and 114 were females (84.4%). Patients’ ages ranged from 18 to 73, with a mean age of 48.13 years (SD = 14.12). Most participants were of Greek origin (97%), residents of urban areas (53.3%), married (60%), and not working (59.3%). Moreover, most patients were chronic since 120 (80%) had MDD onset longer than two years prior to the assessment. Among patients receiving pharmacotherapy (77% of the total sample), most were treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (34.1%), followed by patients treated with combinations of antidepressants (14.8%), while eight patients (5.9%) received no antidepressants and were treated with other medications (e.g., anxiolytics and atypical antipsychotics). In general, half of the patients receiving pharmacotherapy (36.3% of total sample) were treated with more than one medication (e.g., antidepressants and anxiolytics). Futhermore, one-third of the patients (34%) were receiving psychotherapy. Among them, most were receiving supportive therapy (14.1%), followed by Cognitive Analytic (6.7%), and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (5.2%). Patients who participated in T2 and T3 did not differ significantly from those who did not participate in T2 and T3 on gender, age, education, working status, marital status, duration of MDD, pharmacotherapy, and psychotherapy. Patients recruited from online peer support presented some differences from hospital-based patients. Specifically, patients from online peer support were more often better educated (elementary school 0% vs. 30.15%, junior high school 11.11% vs. 9.52%, high school 22.22% vs. 33.33%, vocational training 33.33% vs. 7.93%, university degree 33.33% vs. 19.04%, χ2(4,N = 135) = 9.92, p = .042). Moreover, online peer support patients were more likely to be working (77.77% vs. 38.09% two-tailed p = .031) and receiving psychotherapy (88.88% vs. 30.15% two-tailed p = .001).

Bivariate correlations between the study variables

The five schema domains were significantly correlated with impact and control representations, maladaptive coping, and MDD outcomes. Illness representations were linked to all coping styles and MDD outcomes. All coping styles were correlated with MDD outcomes as well. In general, schema domains were linked to lower control and higher impact representations, and worse MDD outcomes. High control representations were associated with more problem-focused and emotion-focused coping, less maladaptive coping, and better MDD outcomes. High impact representations were linked to less problem-focused and emotion-focused coping, more maladaptive coping and worse MDD outcomes. Finally, problem-focused and emotion-focused coping were linked to better MDD outcomes, and maladaptive coping was linked to worse MDD outcomes. Intercorrelations, means, and standard deviations are presented in Table 2.

Confounding variables

No significant differences in schema domains, illness representations, coping, and MDD outcomes were found with respect to gender Wilks’ λ = .881, F(12, 122) = 1.37, p > .05, partial η2 = .119 and hospitalizations Wilks’ λ = .852, F(12, 122) = 1.76, p > .05, partial η2 = .148. Significant differences in schema domains, illness representations, coping, and MDD outcomes were observed with respect to marital status Wilks’ λ = .575, F(24, 242) = 3.21, p = .000, partial η2 = .242, educational level Wilks’ λ = .572, F(48, 460) = 1.49, p = .021, partial η2 = .130, working status Wilks’ λ = .839, F(12, 122) = 1.95, p = .034, partial η2 = .161, duration of MDD Wilks’ λ = .565, F(48, 460) = 1.53, p = .016, partial η2 = .133, pharmacotherapy Wilks’ λ = .735, F(12, 122) = 3.66, p = .000, partial η2 = .265, and psychotherapy Wilks’ λ = .768, F(12, 122) = 3.07, p = .001, partial η2 = .223. Age was significantly correlated with all schema domains except Other-Directedness, and it was also significantly correlated with problem-focused coping and suicide risk. Hence, age, marital status, educational level, working status, duration of MDD, pharmacotherapy, and psychotherapy were used as control variables in the path analytical models.

Path analytical models

The originally hypothesized complete mediation model (Model 1) provided very good fit to the data (χ2 = 49.811, df = 42, p = .190, χ2/ df = 1.186, CFI = .99, NFI = .96, IFI = .99, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .37, SRMR = .042). The corresponding partial mediation model (Model 2) allowing, in addition, direct paths from schema domains to suicide risk, provided good fit to the data as well (χ2 = 44.378, df = 37, p = .189, χ2/ df = 1.199, CFI = .99, NFI = .96, IFI = .99, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .039, SRMR = .041). A test of the difference between Models 1 and 2 indicated that the two models fit the data equally well (Δχ2 = 5.433, df = 5, p = .36). Since the two models had an equivalently good fit, following established procedures (Keith, 2006), the full mediation model was favored as more parsimonious (df = 42 vs. 37). In addition, examination of the critical ratios of the direct paths from schema domains to suicide risk did not reveal any significant path. In Model 1, the total effects of Impaired Autonomy and Performance on impact representations, control representations, maladaptive coping, and suicide risk were significant. Moreover, the effect of Impaired Autonomy and Performance on suicide risk was significantly mediated by impact representations and MDD severity. Finally, problem-focused coping was linked to suicide risk through MDD symptom severity. Total, direct, and indirect effects are presented in Table 3.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the associations among MDD patients’ schema domains, symptom severity, and suicide risk, as well as the possible mediating role of illness representations and coping in the aforementioned relationships. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining the role of EMS domains, one of the main concepts of Schema Therapy, and illness representations and coping, two key illness-related self-regulation processes in symptom severity and suicide risk in MDD. Results suggest that representations about MDD’s impact and depressive symptom severity serially mediate the association between Impaired Autonomy and Performance and suicide risk in MDD, while problem-focused coping is also linked to suicide risk through MDD severity.

The first significant finding of this study is that Impaired Autonomy and Performance appeared to contribute to negative representations about MDD’s impact, thus leading to higher symptom severity, and ultimately to higher suicide risk. It seems that MDD patients’ difficulties in differentiating themselves from significant others and functioning independently are associated with perceiving MDD as more impactful (e.g., as having more detrimental consequences). In turn, patients’ representations of MDD’s impact lead to higher symptom severity, and increased suicide risk. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous data concerning the role of schema domains in illness representations and coping in MDD. However, current literature links illness representations to MDD patients’ coping strategies (Brown et al., 2001, 2007; Kelly et al., 2007; Mavroeides & Koutra, 2022), and suggests that coping mediates the association between illness representations and MDD outcomes (Brown et al., 2007). In our study, illness representations were linked to coping in a predictable way. Specifically, control representations were linked to more adaptive problem-focused coping and impact representations were linked to more maladaptive coping in line with current literature and theory (Hagger et al., 2017; Leventhal et al., 1980, 2003). Moreover, results suggest that MDD severity acts as a mediator between schema domains, illness representations, and suicide risk. This finding is not surprising, since depressive symptom severity is consistently considered a risk factor for suicide in MDD (Handley et al., 2018; Moller et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2015).

In our study, Impaired Autonomy and Performance was the only schema domain which was found to contribute to increased suicide risk. Concerning the role of autonomy in MDD, Beeker et al. (2017) argue that MDD patients are characterized by a particular kind of autonomy deficits since they may be capable of thinking rationally, but at the same time, they may be unable to behave the way they want to. Indeed, previous studies investigating the role of schema domains in MDD highlight the associations of Impaired Autonomy and Performance with MDD outcomes (Halvorsen et al., 2010; Renner et al., 2012). However, our findings differ from studies which investigated specific EMS, not schema domains, in association with suicide risk in MDD. Flink et al. (2017) found that MDD patients with suicidal ideation scored higher than MDD patients without suicidal ideation on various EMS. Specifically, patients with suicidal ideation scored higher on four EMS of the Disconnection and Rejection domain (Mistrust/Abuse, Emotional Deprivation, Defectiveness/ Shame, Social Isolation/ Alienation), three EMS of the Impaired Autonomy domain (Dependence/ Incompetence, Vulnerability to Harm or Illness, Failure), two EMS of the Other-Directedness domain (Subjugation, Self-sacrifice), and two EMS of the Overvigilance and Inhibition domain (Negativity/ Pessimism, Punitiveness). However, after controlling for MDD symptom severity and hopelessness, only Vulnerability to Harm or Illness remained a significant predictor of suicidal ideation. Moreover, according to Ahmadpanah et al. (2017), various EMS are linked to history of suicide attempts in MDD. Specifically, suicide attempters diagnosed with MDD had higher scores than non-attempters on all EMS of the Disconnection and Rejection domain, on the Dependence/ Incompetence, Vulnerability to Harm or Illness, and Failure EMS from the Impaired Autonomy and Performance domain, and on Emotional Inhibition and Punitiveness from Overvigilance and Inhibition.

Another significant, rather surprising finding was that problem-focused coping was the only coping style linked to MDD clinical outcomes in this study. Specifically, problem-focused coping was linked to lower suicide risk through lower depressive symptom severity. Although previous studies found a negative association between problem-focused coping and MDD outcomes, there have been several reports on the role of maladaptive and emotion-focused coping as well (Di Marco et al., 2017; McWilliams et al., 2003; Suciu et al., 2021). In our study, coping styles were linked to outcomes in the bivariate analyses, but not in the SEM model. Given the purported role of cognitions in MDD (Abramson et al., 1989; Beck & Haigh, 2014; Reilly et al., 2012), it is likely that illness representations take up most of the explanatory variance in MDD severity and suicide risk, when both representations and coping are included in the same model.

From a cultural perspective, Greek MDD patients’ autonomy deficits could be associated with social attitudes towards relationships and cohesion. According to Young et al. (2003), the origins of the Impaired Autonomy and Performance domain EMS lie in enmeshed and overprotective families. Indeed Greek families are characterized by a high degree of enmeshment (Tsamparli & Kounenou, 2004; Tsibidaki & Tsamparli, 2009) and in some cases consider enmeshment as the ideal way of family functioning in terms of cohesion (Tsamparli et al., 2011; Tsibidaki & Tsamparli, 2009). Social emphasis on tight connections, especially inside the family context, may be responsible for deficient growth of autonomy during early childhood, which in turn appear to play a critical role in impairing self-regulation and leading to higher symptom severity and suicide risk during an MDD episode in adult life.

Strengths and limitations

This study’s major strength was its prospective design that permits conclusions regarding causality between the observed associations. Moreover, the sample was relatively homogeneous and naturalistic since we included individuals clinically diagnosed with MDD who did not just screen positive for depression, and most of whom were treated in the same psychiatric facility, using similar procedures and protocols. Finally, validated instruments were used to measure the main variables. Nevertheless, certain limitations of our study need to be acknowledged, too. First, we used self-report questionnaires, which can be subject to social desirability response bias and may inflate associations due to shared variance. Moreover, although this was a prospective study with a satisfactory time interval between its three phases, studies with more repeated measurements would establish more robust mediating effects. Additionally, diagnostic procedures may have not been identical between hospital-based and online peer support patients, however a clinical diagnosis was available in both cases. Furthermore, the majority of our sample consisted of women and the size of our sample was considered modest. Finally, our sample can be considered selective, since it comprised patients diagnosed with MDD without other psychiatric comorbidities.

Clinical implications

This study’s findings have significant implications at a theoretical and practical level. At a theoretical level, this study sheds some light on the relationship between patients’ EMS, self-regulation processes and clinical outcomes in the context of MDD, thus underlining the need to examine further the effect of EMS on the course and outcome of MDD and the intrapersonal mechanisms through which these effects may be exerted. Although various studies identify significant associations between EMS and MDD symptoms and outcomes, the role of patients’ self-regulation processes in this relationship is largely unknown. Future studies should further examine the 18 specific EMS in association with illness representations and coping, as well as in association with other self-regulation skills, such as emotion regulation in MDD.

At a practical level, our study can inform future development of Schema Therapy interventions aimed at enhancing MDD patients’ self-regulation and thus improving MDD clinical outcomes. By modifying EMS, especially within the Impaired Autonomy and Performance domain, restructuring patients’ representations about MDD’s impact, and enhancing problem-focused coping clinicians could more effectively reduce symptom severity and suicide risk in MDD. Moreover, this study’s findings could help improve relapse prevention in MDD since patients’ schemas (Dozois et al., 2014; Farb et al., 2015) and coping (Bockting et al., 2006; Conradi et al., 2008; ten Doesschate et al., 2010) are believed to play a role in MDD recurrence.

Conclusion

Representations about MDD’s impact and MDD severity mediate Impaired Autonomy and Performance’s effects on suicide risk in MDD, while problem-focused coping plays a minor role, too. Targeting EMS within the Impaired Autonomy and Performance domain, restructuring patients’ representations of MDD’ impact, and enhancing patients’ problem-focused coping could be promising for reducing suicide risk in MDD.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96(2), 358–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.2.358

Ahmadpanah, M., Astinsadaf, S., Akhondi, A., Haghighi, M., Sadeghi Bahmani, D., Nazaribadie, M., Jahangard, L., Holsboer-Trachsler, E., & Brand, S. (2017). Early maladaptive schemas of emotional deprivation, social isolation, shame and abandonment are related to a history of suicide attempts among patients with major depressive disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 77, 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.05.008

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Antoniades, J., Mazza, D., & Brijnath, B. (2017). Becoming a patient-illness representations of depression of Anglo-Australian and Sri Lankan patients through the lens of Leventhal’s illness representational model. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 63(7), 569–579. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764017723669

Babajani, S., Akrami, N., & Farahani, A. (2014). Relationship between early maladaptive schemas and coping styles with stress. Journal of Life Science and Biomedicine, 4(6), 570–574.

Bach, B., Lockwood, G., & Young, J. E. (2018). A new look at the schema therapy model: Organization and role of early maladaptive schemas. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(4), 328–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2017.1410566

Basta, M., Micheli, K., Koutra, K., Fountoulaki, M., Dafermos, V., Drakaki, M., Faloutsos, K., Soumaki, E., Anagnostopoulos, D., Papadakis, N., & Vgontzas, A. N. (2022). Depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults in Greece: Prevalence and associated factors. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 8, 100334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2022.100334

Basta, M., Micheli, K., Simos, P., Zaganas, I., Panagiotakis, S., Koutra, K., Krasanaki, C., Lionis, C., & Vgontzas, A. (2021). Frequency and risk factors associated with depression in elderly visiting primary health care (PHC) settings: Findings from the Cretan aging cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 4, 100109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100109

Beck, A. T., & Haigh, E. A. P. (2014). Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: The generic cognitive model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153734

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mpck, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4(6), 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004

Beeker, T., Schlaepfer, T. E., & Coenen, V. A. (2017). Autonomy in depressive patients undergoing DBS-treatment: Informed consent, freedom of will and DBS’ potential to restore it. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 11, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2017.00011

Bishop, A., Younan, R., Low, J., & Pilkington, P. D. (2021). Early maladaptive schemas and depression in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 29(1), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2630

Bockting, C. L. H., Spinhoven, P., Koeter, M. W. J., Wouters, L. F., Visser, I., & Schene, A. H. (2006). Differential predictors of response to preventive cognitive therapy in recurrent depression: A 2-year prospective study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 75(4), 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1159/000092893

Brown, C., Battista, D. R., Sereika, S. M., Bruehlman, R. D., Dunbar-Jacob, J., & Thase, M. E. (2007). Primary care patients’ personal illness models for depression: Relationship to coping behavior and functional disability. General Hospital Psychiatry, 29(6), 492–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GENHOSPPSYCH.2007.07.007

Brown, C., Dunbar-Jacob, J., Palenchar, D. R., Kelleher, K. J., Bruehlman, R. D., Sereika, S., & Thase, M. E. (2001). Primary care patients’ personal illness models for depression: A preliminary investigation. Family Practice, 18(3), 314–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/FAMPRA/18.3.314

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Cannon, M., Credé, M., Kimber, J. M., Brunkow, A., Nelson, R., & McAndrew, L. M. (2022). The common-sense model and mental illness outcomes: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, n/a(n/a). https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2721

Carroll, L. (2013). Problem-focused coping. In M. D. Gellman & J. R. Turner (Eds.), Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine (pp. 1540–1541). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_1171

Carver, C. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’ too long: Consider the brief cope. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267

Cheung, G. W., & Lau, R. S. (2007). Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 296–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428107300343

Conradi, H. J., de Jonge, P., & Ormel, J. (2008). Prediction of the three-year course of recurrent depression in primary care patients: Different risk factors for different outcomes. Journal of Affective Disorders, 105(1), 267–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.04.017

Cooper, C., Katona, C., & Livingston, G. (2008). Validity and reliability of the brief COPE in carers of people with dementia: The LASER-AD study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196(11) https://journals.lww.com/jonmd/Fulltext/2008/11000/Validity_and_Reliability_of_the_Brief_COPE_in.7.aspx

De Berardis, D., Olivieri, L., Rapini, G., Serroni, N., Fornaro, M., Valchera, A., Carano, A., Vellante, F., Bustini, M., Serafini, G., Pompili, M., Ventriglio, A., Perna, G., Fraticelli, S., Martinotti, G., & Di Giannantonio, M. (2020). Religious coping, hopelessness, and suicide ideation in subjects with first-episode major depression: An exploratory study in the real world clinical practice. Brain Sciences, 10(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10120912

Dempster, M., Howell, D., & McCorry, N. K. (2015). Illness perceptions and coping in physical health conditions: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 79(6), 506–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPSYCHORES.2015.10.006

Di Marco, S., Feggi, A., Cammarata, E., Girardi, L., Bert, F., Scaioli, G., Gramaglia, C., & Zeppegno, P. (2017). Schizophrenia and major depression: Resilience, coping styles, personality traits, self-esteem and quality of life. European Psychiatry, 41(S1), S192–S193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.2125

Dozois, D. J. A., Bieling, P. J., Evraire, L. E., Patelis-Siotis, I., Hoar, L., Chudzik, S., McCabe, K., & Westra, H. A. (2014). Changes in core beliefs (early maladaptive schemas) and self-representation in cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 7(3), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2014.7.3.217

Economou, M., Angelopoulos, E., Peppou, L. E., Souliotis, K., Tzavara, C., Kontoangelos, K., Madianos, M., & Stefanis, C. (2016). Enduring financial crisis in Greece: Prevalence and correlates of major depression and suicidality. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(7), 1015–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1238-z

Economou, M., Madianos, M., Peppou, L. E., Patelakis, A., & Stefanis, C. N. (2013). Major depression in the era of economic crisis: A replication of a cross-sectional study across Greece. Journal of Affective Disorders, 145(3), 308–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.008

Farb, N. A. S., Irving, J. A., Anderson, A. K., & Segal, Z. V. (2015). A two-factor model of relapse/recurrence vulnerability in unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000031

Ferrari, A. J., Charlson, F. J., Norman, R. E., Flaxman, A. D., Patten, S. B., Vos, T., & Whiteford, H. A. (2013). The epidemiological modelling of major depressive disorder: Application for the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS One, 8(7), e69637.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069637

Flink, N., Lehto, S. M., Koivumaa-Honkanen, H., Viinamäki, H., Ruusunen, A., Valkonen-Korhonen, M., & Honkalampi, K. (2017). Early maladaptive schemas and suicidal ideation in depressed patients. The European Journal of Psychiatry, 31(3), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpsy.2017.07.001

Fountoulakis, K. N., Pantoula, E., Siamouli, M., Moutou, K., Gonda, X., Rihmer, Z., Iacovides, A., & Akiskal, H. (2012). Development of the Risk Assessment Suicidality Scale (RASS): A population-based study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 138(3), 449–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.045

Hagger, M. S., Koch, S., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., & Orbell, S. (2017). The common sense model of self-regulation: meta-analysis and test of a process model. Psychological Bulletin, 143(11), 1117–1154. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000118

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

Halvorsen, M., Wang, C. E., Eisemann, M., & Waterloo, K. (2010). Dysfunctional attitudes and early maladaptive schemas as predictors of depression: A 9-year follow-up study. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34(4), 368–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-009-9259-5

Halvorsen, M., Wang, C. E., Richter, J., Myrland, I., Pedersen, S. K., Eisemann, M., & Waterloo, K. (2009). Early maladaptive schemas, temperament and character traits in clinically depressed and previously depressed subjects. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 16(5), 394–407. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.618

Handley, T., Rich, J., Davies, K., Lewin, T., & Kelly, B. (2018). The challenges of predicting suicidal thoughts and behaviours in a sample of rural Australians with depression. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050928

Holubova, M., Prasko, J., Ociskova, M., Grambal, A., Slepecky, M., Marackova, M., Kamaradova, D., & Zatkova, M. (2018). Quality of life and coping strategies of outpatients with a depressive disorder in maintenance therapy - a cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14, 73–82. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S153115

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2013). An introduction to statistical learning: With applications in R. Springer.

Jang, T. Y., & Lee, S. J. (2020). Characteristics of early maladaptive schemas in individuals with schizophrenia: A comparative study relative to major depressive disorder. Korean Journal of Schizophrenia Research, 23(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.16946/kjsr.2020.23.1.29

Jemos, J. (1984). The standardization of the Beck depression inventory in a Greek population sample. National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Kalaitzaki, A. (2021). Posttraumatic symptoms, posttraumatic growth, and internal resources among the general population in Greece: A nation-wide survey amid the first COVID-19 lockdown. International Journal of Psychology, 56(5), 766–771. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12750

Kapsou, M., Panayiotou, G., Kokkinos, C. M., & Demetriou, A. G. (2010). Dimensionality of coping: An empirical contribution to the construct validation of the brief-COPE with a Greek-speaking sample. Journal of Health Psychology, 15(2), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105309346516

Ke, T., & Barlas, J. (2020). Thinking about feeling: Using trait emotional intelligence in understanding the associations between early maladaptive schemas and coping styles. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 93(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12202

Keith, T. Z. (2006). Multiple regression and beyond. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.

Kelly, M. A. R., Sereika, S. M., Battista, D. R., & Brown, C. (2007). The relationship between beliefs about depression and coping strategies: Gender differences. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46(Pt 3), 315–332. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466506X173070

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

Leventhal, H., Brissette, I., & Leventhal, E. A. (2003). The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. In L. Cameron & H. Leventhal (Eds.), The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour (pp. 42–65). Routledge.

Leventhal, H., Meyer, D., & Nerenz, D. (1980). The common sense model of illness danger. Rachman, S.(ed.) medical psychology. In S. Rachman (Ed.), Contributions to medical psychology (pp. 7–30). Pergamon.

Lu, Y., Tang, C., Liow, C. S., Ng, W. W. N., Ho, C. S. H., & Ho, R. C. M. (2014). A regressional analysis of maladaptive rumination, illness perception and negative emotional outcomes in Asian patients suffering from depressive disorder. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 12(1), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AJP.2014.06.014

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

Madianos, M., Economou, M., Alexiou, T., & Stefanis, C. (2011). Depression and economic hardship across Greece in 2008 and 2009: Two cross-sectional surveys nationwide. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 46(10), 943–952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0265-4

Malogiannis, I., Aggeli, A., Garoni, D., Tzavara, C., Michopoulos, I., Pehlivanidis, A., Kalantzi-Azizi, A., & Papadimitriou, G. N. (2018). Validation of the Greek version of the Young Schema questionnaire-short form 3: Internal consistency reliability and validity. Psychiatriki, 29, 220–230. https://doi.org/10.22365/jpsych.2018.293.220

Mavroeides, G., & Koutra, K. (2021). Illness representations in depression and their association with clinical and treatment outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 4, 100099. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JADR.2021.100099

Mavroeides, G., & Koutra, K. (2022). Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Greek version of the illness perception questionnaire- mental health in individuals with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Research Communications, 2, 100026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psycom.2022.100026

Mc Donnell, E., Hevey, D., McCauley, M., & Ducray, K. N. (2018). Exploration of associations between early maladaptive schemas, impaired emotional regulation, coping strategies and resilience in opioid dependent poly-drug users. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(14), 2320–2329. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2018.1473438

McWilliams, L. A., Cox, B. J., & Enns, M. W. (2003). Use of the coping inventory for stressful situations in a clinically depressed sample: Factor structure, personality correlates, and prediction of distress1. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59(12), 1371–1385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10228

Menard, S. (1995). Applied logistic regression analysis: Sage university series on quantitative applications in the social sciences. Sage.

Meuwissen, T. H. E., & Goddard, M. E. (2004). Bootstrapping of gene-expression data improves and controls the false discovery rate of differentially expressed genes. Genetics Selection Evolution, 36(2), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1051/gse:2003058

Moller, C. I., Cotton, S. M., Badcock, P. B., Hetrick, S. E., Berk, M., Dean, O. M., Chanen, A. M., & Davey, C. G. (2021). Relationships between different dimensions of social support and suicidal ideation in young people with major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 714–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.085

Orzechowska, A., Zajączkowska, M., Talarowska, M., & Gałecki, P. (2013). Depression and ways of coping with stress: A preliminary study. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, 19, 1050–1056. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.889778

Reichardt, J., Ebrahimi, A., Nasiri Dehsorkhi, H., Mewes, R., Weise, C., Afshar, H., Adibi, P., Moshref Dehkordy, S., Yeganeh, G., Reich, H., & Rief, W. (2018). Why is this happening to me? A comparison of illness representations between Iranian and German people with mental illness. BMC Psychology, 6(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0250-3

Reilly, L. C., Ciesla, J. A., Felton, J. W., Weitlauf, A. S., & Anderson, N. L. (2012). Cognitive vulnerability to depression: A comparison of the weakest link, keystone and additive models. Cognition & Emotion, 26(3), 521–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.595776

Renaud, J., Dobson, K. S., & Drapeau, M. (2014). Cognitive therapy for depression: Coping style matters. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 14(1), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2012.758754

Renner, F., Lobbestael, J., Peeters, F., Arntz, A., & Huibers, M. (2012). Early maladaptive schemas in depressed patients: Stability and relation with depressive symptoms over the course of treatment. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136(3), 581–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.027

Rodgers, S., Vandeleur, C. L., Strippoli, M.-P. F., Castelao, E., Tesic, A., Glaus, J., Lasserre, A. M., Müller, M., Rössler, W., Ajdacic-Gross, V., & Preisig, M. (2017). Low emotion-oriented coping and informal help-seeking behaviour as major predictive factors for improvement in major depression at 5-year follow-up in the adult community. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(9), 1169–1182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1421-x

Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Hergueta, T., Baker, R., & Dunbar, G. C. (1998). The Mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59, 22–33.

Sinha, B. K., & Watson, D. C. (2007). Stress, coping and psychological illness: A cross-cultural study. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(4), 386–397. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.14.4.386

Skinner, T. C., Carey, M. E., Cradock, S., Dallosso, H. M., Daly, H., Davies, M. J., Doherty, Y., Heller, S., Khunti, K., Oliver, L., & Collaborative, on behalf of T. D. (2011). Comparison of illness representations dimensions and illness representation clusters in predicting outcomes in the first year following diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: Results from the DESMOND trial. Psychology & Health, 26(3), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903411039

Strauman, T. J., & Eddington, K. M. (2017). Treatment of depression from a self-regulation perspective: Basic concepts and applied strategies in self-system therapy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-016-9801-1

Suciu, B. D., Păunescu, R. L., & Micluţia, I. V. (2021). Coping strategies in an euthymic phase for major depressed patients. The European Journal of Psychiatry, 35(3), 140–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpsy.2021.03.003

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Pearson.

ten Doesschate, M. C., Bockting, C. L. H., Koeter, M. W. J., & Schene, A. H. (2010). Prediction of recurrence in recurrent depression: A 5.5-year prospective study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(8), 984–991. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.08m04858blu

Tsamparli, A., & Kounenou, K. (2004). The Greek family system when a child has diabetes mellitus type 1. Acta Paediatrica, 93(12), 1646–1653. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb00857.x

Tsamparli, A., Tsibidaki, A., & Roussos, P. (2011). Siblings in Greek families: Raising a child with disabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 13(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2010.540910

Tsibidaki, A., & Tsamparli, A. (2009). Adaptability and cohesion of Greek families: Raising a child with a severe disability on the island of Rhodes. Journal of Family Studies, 15(3), 245–259. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.15.3.245

Wang, C. E. A., Halvorsen, M., & Eisemann, M. (2010). Stability of dysfunctional attitudes and early maladaptive schemas: A 9-year follow-up study of clinically depressed subjects. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 41(4), 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.04.002

Wang, Y., Jiang, N., Cheung, E. F. C., Sun, H., & Chan, R. C. K. (2015). Role of depression severity and impulsivity in the relationship between hopelessness and suicidal ideation in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 183, 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.001

Williams, J., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Resampling and distribution of the product methods for testing indirect effects in complex models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 15(1), 23–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701758166

Witteman, C., Bolks, L., & Hutschemaekers, G. (2011). Development of the illness perception questionnaire mental health. Journal of Mental Health, 20(2), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2010.507685

World Medical Association. (2013). World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053

Young, J. (2005). Young Schema questionnaire- short form 3. New York, NY: Cognitive Therapy Center.

Young, J. E. (1999). Cognitive therapy for personality disorders: A schema-focused approach, 3rd ed. In In cognitive therapy for personality disorders: A schema-focused approach, 3rd ed. Professional Resource Press/Professional Resource Exchange.

Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishaar, M. E. (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. Guilford Press.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all patients who participated in this study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece. This work was supported by the University of Crete’s Special Account for Research Grants [grant number 4203].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mavroeides, G., Basta, M., Vgontzas, A. et al. Early maladaptive schema domains and suicide risk in major depressive disorder: the mediating role of patients’ illness-related self-regulation processes and symptom severity. Curr Psychol 43, 4751–4765 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04682-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04682-2