Abstract

The Dyadic-Familial Relationship Satisfaction Scale (DFRSS) is a valid and reliable instrument to assess dyadic and familial dimensions of relationship satisfaction in cohabitant couples with children. The main goal of this research was to validate the Spanish version of the DFRSS (Sp-DFRSS) following the guidelines for cross-cultural adaptations. Three studies were conducted. In Study 1 (n = 151), an exploratory factor analysis using principal axis factoring and oblimin rotation was performed to examine the factor structure of the Sp-DFRSS. In Study 2 (n = 500), a confirmatory factor analysis showed that a two factor model (dyadic and familial) provided the best fit to the data. In Study 3 (n = 100), we examined relationship satisfaction using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. The Sp-DFRSS as a whole and its subscales presented adequate reliability in the three studies, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from 0.87 to 0.95. Moreover, convergent and divergent validity of the Sp-DFRSS was analyzed in Studies 1, 2 and 3, and significant correlations between the Sp-DFRSS’ subscales, life satisfaction, negative and positive affect, attachment (anxiety and avoidance), and psychological well-being were found. The Sp-DFRSS has good psychometric properties in terms of validity and reliability, so that it may be used by the Spanish-speaking scientific community to measure relationship satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Marriage and similar intimate adult relationships affect profoundly the lives of individuals across virtually all cultures (Buss, 1995). Relationship satisfaction is a complex construct designed to measure the interpersonal evaluation of the positivity of feelings for one’s partner and attraction to the relationship (Keizer, 2014). Successful satisfying relationship is a core ingredient for psychological and physical well-being: persons with gratifying romantic relationships have happier, healthier, and longer lives (Diamond et al., 2010; Ruffieux et al., 2014) and they tend to report less stress, anxiety, and depression, as well as increased life satisfaction and well-being (Roberson et al., 2018; Saxbe & Repetti, 2010; Schudlich et al., 2011).

Many scales have been developed and adapted in different countries to assess relationship satisfaction (for a meta-analysis, see Graham et al., 2011). The Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976), the Marital Adjustment Test (Locke & Wallace, 1959), the Quality of Marriage Index (Norton, 1983), the Relationship Assessment Scale (Hendrick, 1988), and the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale (Schumm et al., 1983) are among the most used measures of relationship satisfaction. Although they have been proved to be valid and reliable instruments, the items of all these scales do not distinguish between dyadic (the satisfaction with the partner) and familial (the satisfaction with the familial life) aspects of relationship satisfaction.

In order to differentiate dyadic from familial satisfaction, Raffagnino and Matera (2015) developed the Dyadic-Familial Relationship Satisfaction Scale (DFRSS) (see Appendix Table 5) in Italy. According to these authors, when defining relationship satisfaction, it would be useful to distinguish couples who live together and have children from couples who do not share the same house and do not have children. While a dyadic dimension of satisfaction is supposed to be common to both, a familial dimension should only be considered for cohabitant couples with children.

The dyadic dimension involves the relationship with one’s partner, independently of third elements, such as the household or other family members (for a systematic review, see Jiménez-Picón et al., 2021). Level of commitment, time spent together, sharing activities, experiences and network, commonality of objectives, cooperation, making decisions together, support and respect, as well as good interpersonal communication are all elements predicting dyadic relationship satisfaction. For the familial dimension, other factors have to be considered, like family commitment, home management, and partners’ perceived housework equity. The familial dimension might also include the bond with one’s partner’s family of origin, which can be characterized by support, solidarity, or conflict, and for couples with children, child management and education have to be considered as well (Raffagnino & Matera, 2015).

Based on the two dimensions considered (dyadic and familial), Raffagnino and Matera (2015) individuated a total of 19 domains, each covered by specific items. An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) yielded a two-factor solution, as predicted. One item had to be eliminated, as it did not load significantly on any factor. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) performed on another sample led to eliminate further four items which emerged as redundant. The two-factor solution was confirmed, with the final 14-item model showing a very good fit to the data. The two subscales presented high internal consistency. Both were significantly correlated with an overall index of satisfaction, which confirmed the construct validity of the scale. Known groups validity, examined by comparing the scores obtained on the scale by a clinical and a nonclinical sample, was good as well. Gender differences were found, showing that women were more unsatisfied with their relationship than men (Amato et al., 2007). Further studies confirmed the good psychometric properties of the scale in the Italian context (e.g., Agus et al., 2021).

Research overview

Considering the utility of a scale that permits to capture not only the dyadic, but also the familial dimension of relationship satisfaction, the aim of this research was to adapt the DFRSS to Spanish-speaking populations. Previous research has found systematic differences between cultures in response style when participants answer scale items (Harzing, 2006), and, for this reason, we think that cross-cultural studies, such as ours, are important in demonstrating the generalizability of questionnaires to measure relationship satisfaction (Gere & MacDonald, 2012). Furthermore, we believe that studying relationship satisfaction within the Spanish sociocultural context is especially important given that the divorce rate in Spain is the highest in Europe, with two out of every four (58%) marriages ending in divorce (Eurostat, 2017). In addition, we believe that measures developed for Spanish-speaking cohabitant couples with children are particularly useful, given that Spanish ranks second among languages in worldwide prevalence with more than 480 million speakers (Eberhard et al., 2019).

We carried out three studies to achieve the goal of adapting the DFRSS in Spain. In Study 1 we developed the Spanish version of the scale (Sp-DFRSS) with a sample of members of cohabitant couples with children. In this first study, we examined its psychometric properties through an EFA, and we analyzed its convergent validity by examining associations between the dyadic and familial dimensions of relationship satisfaction and life satisfaction.

In Study 2 we examined further the dimensionality of the Sp-DFRSS through a CFA with a different sample of members of cohabitant couples with children. In this second study, we analyzed its convergent and divergent validity examining if dyadic and familial dimensions of relationship satisfaction were associated with attachment and affect.

Finally, in Study 3, relationship satisfaction measured through the Sp-DFRSS was examined with a sample of cohabitant couples with children using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM). In this third study, we analyzed the associations between the dyadic and familial dimensions of relationship satisfaction and psychological well-being.

Study 1

Objectives

Through this Study 1 we developed the Sp-DFRSS. The adaptation of the DFRSS was a complex task that required careful planning to ensure its content maintenance for the Spanish population. For this reason, the DFRSS was adapted to Spanish using the translation/back-translation methodology and following the guidelines for cross-cultural adaptations (Hernández et al., 2020).

With respect to the Sp-DFRSS’ convergent validity, we examined the scale’s association with a measure of life satisfaction. Previous research has shown that intimate relationships are closely linked to life satisfaction, and that individuals with satisfying and gratifying romantic relationships have happier lives (Diamond et al., 2010) and are likely to experience increased life satisfaction (Saxbe & Repetti, 2010; Schudlich et al., 2011). Moreover, recent longitudinal research has shown that relationship satisfaction and life satisfaction are mutually influential over time (Roberson et al., 2018). For these reasons, we expected to find a positive association between the two dimensions of relationship satisfaction of the Sp-DFRSS and life satisfaction.

Method

Participants

The participants were 151 heterosexual individuals (74.8% women) in couple, aged between 18 and 65 years (M = 42.64, SD = 8.33). All participants lived with their partner, with a mean duration of their relationship of 16.69 years (SD = 9.72) and a range of 2 to 40 years. All participants also had children from this relationship: 35.1% had one child, 50.3% had two children, 11.3% had three children, and 3.3% had four children.

Data collection and ethical concerns

Information about the research was posted on the Social Psychology’s virtual course taught by one of the authors of this study in order to request assistance by students from the Spanish Open University (UNED). Voluntary Psychology students were asked to send information of the research to members of cohabitant couples with children of their acquaintance in exchange for course credit. The participants in the final sample had to complete the questionnaires trough Qualtrics, an online survey environment. All of them voluntarily agreed to participate in the study.

Approval was granted by the UNED's Ethical Committee. Participants in the final sample consented to participate in the study, and they were allowed to withdraw from the study whenever they wanted. The data were collected anonymously, and results were reported in aggregate form only, so that participants could not be identified individually. Upon completion of the survey, participants were debriefed online about the purposes of the study.

Adaptation procedure

The first Spanish translation of the original questionnaire in Italian was performed by one of the authors of the current study. This Spanish translation was independently reviewed by another author of this research, who worked with the first translator to reach an agreed-upon translation of the items, especially those which posed the most difficulty from the semantic and/or grammatical standpoint. Afterwards, a bilingual Italian translator back-translated the agreed Spanish translation to Italian, with no knowledge of the original scale in Italian, in order to preserve the reliability of the back-translation. This translation was discussed with experts in the field of relationship satisfaction. Finally, the Sp-DFRSS was tested with a small sample of students before launching the study to ensure that the questionnaire was perfectly clear and understandable, and participants were requested to report if any item was ambiguous or unintelligible. Items of the Sp-DFRSS can be seen in the Appendix Table 5.

Measures

To measure relationship satisfaction, the Sp-DFRSS was used (Raffagnino & Matera, 2015). This questionnaire is composed of two subscales assessing respectively the dyadic (9 items. e.g., “How satisfied I am with the way in which my desires and needs are satisfied within my current relationship”) and the familial (5 items. e.g., “How satisfied I am with responsibility and family commitment”) dimension of satisfaction. A 5-point Likert scale that ranged from not satisfied at all to completely satisfied was used. Subscale scores were calculated by averaging the scores given to each of the items of the factors. The highest score on the subscale indicates greater experience of dyadic or familial satisfaction. In the original study, the internal consistency of the two subscales was very high (α = 0.97 for the dyadic subscale and 0.91 for the familial subscale).

Finally, the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) (Pavot & Diener, 1993; Spanish version: Vazquez et al., 2013) was used to assess life satisfaction. The SWLS is a 5-item measure with a good reliability in our sample (α = 0.89). A 5-point Likert scale that ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree was used. An example of the scale would be “The conditions of my life are excellent”. Higher scores on SWLS reflect greater satisfaction with one’s life as a whole.

Data analysis

Firstly, to evaluate the structure of the Sp-DFRSS, as in the original validation study, an EFA using principal axis factoring and oblimin rotation was performed (Raffagnino & Matera, 2015). Sample size exceeded the minimum 5:1 participants-to-item ratio necessary for EFA. Furthermore, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO = 0.909) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity [χ2(91) = 1976, p < .001] indicated that data were adequate for conducting an EFA. The number of factors was determined by both parallel analysis and the Minimum Average Partial (MAP) using the FACTOR software (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2006). Secondly, the reliability of the Sp-DFRSS and its subscales was analyzed in terms of internal consistency. Cronbach’s alphas ≥ 0.70, 0.80, or 0.90 can be interpreted as acceptable, good, or excellent, respectively. Finally, to analyze the convergent validity of the Sp-DFRSS, the correlations between the dyadic and familial dimensions and life satisfaction were examined. The SPSS 25.0 software package was used to perform the analyses.

Results

Parallel analysis suggested extraction of one factor, which explained 62.5% of variance. However, the MAP test advised the extraction of two factors (averaged squared partial correlation: component 1 = 0.052, component 2 = 0.044). In addition, in the EFA a two-factor solution, accounted for 71.37% of the total variance, was obtained. All of the items reported robust factor loadings (> 0.50) on the expected factor (see Table 1): the first factor (items 1–9) referred to the dyadic dimension, while the second one related to the familial dimension of relationship satisfaction (items 10–14).

The internal consistency of the scale as a whole (α = 0.95) and the two factors was excellent (α = 0.94 and α = 0.89, for the dyadic and the familial components respectively). With respect to the Sp-DFRSS’ convergent validity, both the dyadic and the familial dimensions were significantly correlated to life satisfaction (r = .47, p < .01 and r = .46, p < .01, respectively). Finally, the correlation between the dyadic and familial components was quite high (r = .71, p < .01).

Study 2

Objectives

Through Study 2 we aimed at investigating further both the dimensionality and reliability of the Sp-DFRSS. To confirm the Sp-DFRSS’ structure found in the EFA of the Study 1, a CFA was performed on a separate sample of members of cohabitant couples with children. We decided to test a one and a two-factor model. Both structures were plausible, as the parallel analysis in Study 1 suggested the extraction of one factor, whereas the MAP test suggested the extraction of two subscales. However, we expected to find a two-factor model replicating the original Italian version (Raffagnino & Matera, 2015). To analyze the Sp-DFRSS’ convergent and divergent validity, we assessed its association with both attachment and affect.

The construct of attachment was originally used to characterize the close emotional bond between a child and his or her caregiver. Bowlby (1977) defined attachment as “the propensity of human beings to make strong affectional bonds to particular others” (p. 201). This attachment system was later extended to adult relationships (Fraley et al., 2005). Following this perspective, several studies were carried out in the past two decades (for a review, see Mikulincer & Shaver, 2013). It has been suggested that this attachment system is crucial for maintaining satisfactory relationships (Fraley et al., 2005).

Adult attachment style has been conceptualized in terms of two dimensions, avoidance and anxiety (Fraley & Shaver, 2000). Avoidance refers to discomfort with closeness and interdependence, and attachment anxiety refers to fear of rejection or abandonment (Molero et al., 2016). Secure adults are those who score low on both anxiety and avoidance (Fraley & Shaver, 2000). It has been found that people with either avoidant or anxious styles of attachment are characterized by lower relationship satisfaction (for a meta-analysis, see Li & Chan, 2012). For all these reasons, we expected to find a negative association between the Sp-DFRSS and avoidant an anxiety attachment.

In Study 1 we examined the association between relationship satisfaction and life satisfaction, conceived as the cognitive aspect of subjective well-being. However, researchers claim that subjective well-being also contains an affective component (Diener, 2000). This affective component entails predominance of positive over negative affect. That’s why we thought it useful to examine further the convergent and divergent validity of the Sp-DFRSS by analyzing the association between its dimensions and well-being, conceived not only in terms of high life satisfaction, but also in terms of an appropriate affect balance (Molero et al., 2017). According to the reviewed literature, we expected to find a positive correlation between the dimensions of relationship satisfaction and positive affect, and a negative association between the Sp-DFRSS and negative affect.

Method

Participants

The participants who took part in the study were 500 heterosexual individuals in couple (77.8% women), aged between 18 and 65 years (M = 42.63, SD = 6.63), who lived with their partner (M = 17.94, SD = 6.63) and had children (M = 1.90, SD = 0.73).

Data collection and ethical concerns

The same procedure of Study 1 was used.

Measures

To measure relationship satisfaction, the Sp-DFRSS was used (Raffagnino & Matera, 2015). In addition, participants completed the Spanish version (Alonso-Arbiol et al., 2007) of the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) questionnaire (Brennan et al., 1998). The ECR contains two 18-item scales that measure attachment related respectively to anxiety (e.g., “I worry about being abandoned”) and avoidance (e.g., “I try to avoid getting too close to my partner”). In this study, the Cronbach’s αs were 0.86 and 0.67 for anxiety and avoidance, respectively. A 5-point Likert scale that ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree was used, with higher scores indicating greater attachment anxiety or avoidance.

Finally, the Spanish version (Sandín et al., 1999) of the Positive And Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (Watson et al., 1988) was administered. The PANAS is a 20-item instrument that evaluates positive (10 items) and negative affect (10 items). Respondents answered the items on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in our sample was 0.90 for the positive affect subscale and 0.87 for the negative affect subscale. Higher scores on positive affect reflect greater positive feelings. Higher scores on negative affect reflect greater negative feelings. “Enthusiastic” or “Nervous” would be examples of positive and negative adjectives respectively.

Data analysis

Firstly, a CFA with maximum likelihood parameter estimates was conducted. To assess the fit of a model a combination of indexes was considered. Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was used as an absolute fit index. Values below 0.05 indicate a close fit, from 0.05 to 0.08 a fair fit, from 0.08 to 0.10 a mediocre fit, and above 0.10 an unacceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). As incremental fit indexes, Normed Fit Index (NFI) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) were used. Both CFI and NFI are bound between 0 and 1 and values between 0.90 and 0.95 indicate an acceptable model fit, with values greater than 0.95 indicating a good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Secondly, the Cronbach’s alpha of the scale and its dimensions were calculated. Thirdly, to analyze the convergent and divergent validity of the Sp-DFRSS, the Pearson’s correlation coefficients between dyadic and familial dimensions of relationship satisfaction and both attachment (anxiety and avoidance) and affect (positive and negative) were calculated. The SPSS 25.0 and Amos 25.0 software packages were used to perform the analyses.

Results

The one-factor model was far from a good fit (CFI = 0.820, NFI = 0.810, RMSEA = 0.167). Thus, we tested the fit of a two-factor model. This initial model showed a poor fit as well (CFI = 0.90, NFI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.12), despite each item showed a high and significant correlation with the expected factor (between 0.60 and 0.87). An examination of the modification indices indicated two additions to the resulting model that were theoretically meaningful: the correlation between error terms for items 10 (“how satisfied I am with the management of the children”) and 11 (“how satisfied I am with the education of the children”), and for items 12 (“how satisfied I am with house management”) and 13 (“how satisfied I am with roles and familial tasks division”). The content of items 10 and 11 was very similar (as the management of children involves their education) and the same thing happened with items 12 and 13 (as household management involves the division of roles and tasks).

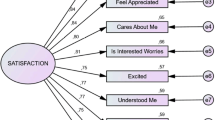

As reported in Fig. 1, this solution, which reflected the two-factor structure that appeared adequate in Study 1, showed a good fit to the data (CFI = 0.96, NFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.08). All of the parameters of the model were statistically significant (p < .001), and the standardized coefficients presented adequate values, between 0.60 and 0.91.

The Sp-DFRSS as a whole had a good reliability in our sample (α = 0.95). The dyadic dimension (α = 0.94) and the familial dimension of relationship satisfaction (α = 0.90) presented high internal consistency as well. Concerning convergent and divergent validity, as reported in Table 2, the dyadic and familial dimensions of relationship satisfaction were significantly associated with both attachment and affect. Specifically, they were both positively related to positive affect (convergent validity) and negatively related to negative affect, anxiety, and avoidance (divergent validity).

Study 3

Objectives

Through this Study 3 we studied relationship satisfaction in a sample of cohabitant couples with children. Specifically, we examined, using the APIM, to what extent the dyadic and familial dimensions of relationship satisfaction could predict both members’ psychological well-being.

Two different views have been described regarding the study of well-being. The subjective well-being perspective, as it has been previously stated in Study 1 and 2, focuses on the hedonic aspect of well-being, and it involves global evaluations of affect and life satisfaction (Diener, 2000). On the other hand, the psychological well-being perspective focuses on eudaimonic well-being, which is the fulfillment of human potential and a meaningful life (Ryff, 1989).

Following this perspective, psychological well-being is a multidimensional construct composed of six aspects: self-acceptance, positive and satisfactory relations with others, the perception of self-determination and autonomy, the sense of mastering inner or outer environmental requests, the perception that life has meaning, and the sense of personal growth (Ryff, 1989).

It has been found that psychological well-being predicted trajectories of marital happiness (Kamp Dush et al., 2008). In addition, psychological well-being has been found as an outcome of meaningful activities such as healthy relationships (Steger et al., 2008). For these reasons, we expected to find a positive association between the two dimensions of the Sp-DFRSS and the different components of psychological well-being.

Method

Participants

The participants consisted of 50 heterosexual couples who lived together (M = 18.26, SD = 6.57), aged between 18 and 65 years (M = 42.02, SD = 6.34), who had children (M = 1.98, SD = 0.69).

Data collection and ethical concerns

The same procedure of Study 1 and 2 was used. In this case, members of the couple were asked to complete the online questionnaires independently. An anonymous four-digit code was generated for each couple and the two members of the couple were instructed to use it when entering into the Qualtrics platform. With this procedure, we were able to identify both members of the couple to complete our analyses. Finally, results were reported in aggregate form only, so that participants could not be identified individually or as a couple.

Measures

Together with the Sp-DFRSS (whole scale, α = 0.90.; dyadic satisfaction, α = 0.87; familial satisfaction, α = 0.89), the Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWBS) (Ryff, 1989; Spanish version: Díaz et al., 2006) was used. PWBS is a 39-item self-report instrument which is based on six dimensions that point to different aspects of positive psychological functioning: self-acceptance (6 items), positive relations with others (6 items), autonomy (8 items), environmental mastery (6 items), purpose in life (6 items), and personal growth (7 items). A 5-point Likert scale that ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree was used. Alpha coefficients obtained for present study were: 0.85 for self-acceptance (e.g., “When I look at the story of my life, I am pleased with how things have turned out”), 0.78 for positive relations with others (e.g., “People would describe me as a giving person, willing to share my time with others”), 0.74 for autonomy (e.g., “I have confidence in my opinions, even if they are contrary to the general consensus”), 0.73 for environmental mastery (e.g., “In general, I feel I am in charge of the situation in which I live”), 0.70 for purpose in life (e.g., “Some people wander aimlessly through life, but I am not one of them”), and 0.84 for personal growth (e.g., “I think it is important to have new experiences that challenge how you think about yourself and the world”). Subscale scores were calculated by averaging the scores given to each of the items of the factors. The highest score on the subscale indicates greater experience of well-being.

Data analysis

Preliminarily, we examined if the two couple members’ data could be considered independent. The correlations between the two members’ scores on dyadic satisfaction (r = .35, p = .01), familial satisfaction (r = .37, p = .01), and psychological well-being (r = .31, p = .03) were significant, so the dyad needed to be explicitly considered in the analysis. In addition, Cohen’s ds were calculated to test if there were gender differences. A commonly used interpretation is to refer to effect sizes as small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), and large (d = 0.8). In addition, we assessed the associations between dyadic and familial satisfaction and the six dimensions of psychological well-being through bivariate correlations. The SPSS 25.0 software package was used to perform the analyses.

The APIM was used to examine if the dyadic and familial dimensions of relationship satisfaction could predict the six psychological well-being dimensions. The APIM was designed to estimate the impact of a person’s predictor variables on his or her own outcome variables (actor effects) and on the outcome variables of the partner (partner effects). The model was compatible with the expected non-independence of dyad members’ variables.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used (Kenny et al., 2006). According to these authors, SEM is the simplest and most straightforward analytic method for estimating the APIM with distinguishable dyads. As recommended by these researchers, unstandardized coefficients were reported. For each model, actor effects for men and women were presented, as well as partner effects running from men to women, and partner effects running from women to men (see Fig. 2).

The data were analyzed using AMOS 25.0 and separate models were conducted for each dimension of psychological well-being. Several indexes were used to test the goodness of fit of the models. Chi-square is suitable for small samples, as in this case. The model shows a good fit when its probability is not significant (p > .05). We also considered the RMSEA, the CFI, and the NFI (see Study 2).

Results

The means and standard deviations for all variables are shown in Table 3, broken down by gender. There were no significant gender differences except for the positive relations with others subscale, on which women scored higher than men. The effect size for this difference was medium (-0.39) according to Cohen’s d.

Table 4 shows the correlations between dyadic and familial satisfaction and the six dimensions of psychological well-being. Significant positive correlations were observed with the two dimensions of relationship satisfaction in most of the psychological well-being subscales, with two exceptions: the autonomy subscale, which showed no significant correlations neither for men (below the diagonal) nor for women (above the diagonal), and the personal relations with others subscale, which showed no significant correlations in women. Patterns of correlations were quite similar for men and women.

The APIM models of relationship satisfaction on each psychological well-being dimension showed a good fit, with CFI and NFI values above 0.98 and RMSEA values very close to 0 in all cases (see Fig. 3).

In the self-acceptance model, we found an actor effect, because women’s familial satisfaction did predict their own scores on self-acceptance (b = 0.32, SE = 0.12, p = .008). There was no significant effect, neither actor nor partner on the positive relations with others subscale.

In the environmental mastery model, we found two actor effects: there was a positive relation between men’s dyadic satisfaction and their own environmental mastery (b = 0.51, SE = 0.19, p = .008), and between women’s dyadic satisfaction and their own environmental mastery score (b = 0.46, SE = 0.16, p = .005). In the personal growth model, we found that dyadic satisfaction was positively associated with personal growth scores for men (b = 0.47, SE = 0.18, p = .012) but not for women.

In the purpose in life model, we found three actor effects: both men’s (b = 0.51, SE = 0.24, p = .038) and women’s (b = 0.40, SE = 0.19, p = .038) dyadic satisfaction predicted their own purpose in life score; moreover, there was a positive association between women’s familial satisfaction and their own purpose in life (b = 0.28, SE = 0.13, p = .027), but this was not the case for men. In addition, there were one significant partner effect: women’s dyadic satisfaction positively predicted men’s purpose in life scores (b = 0.31, SE = 0.18, p = .038).

General discussion

Through Study 1 the Sp-DFRSS was developed. Our two-factor solution cleanly replicated the original Italian version, with all the items reporting robust factor loadings on the expected factor (Raffagnino & Matera, 2015). The reliability of the two components was high, in line with the Italian version of the scale. Evidence of convergent validity was obtained, as the two dimensions of the Sp-DFRSS were significantly associated with participants’ life satisfaction, in line with the literature (Roberson et al., 2018). We can consider this result as expected given the importance of intimate relationships for satisfaction and happiness in Spain (Centro Investigaciones Sociológicas, 2017). We should observe that the DFRSS was translated into Spanish using the translation/back-translation methodology and following the guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation (Hernández et al., 2020).

In Study 2 the CFA confirmed that a two-factor structure of the Sp-DFRSS was the one that best represented the data. Therefore, we can observe that the dimensionality of the Sp-DFRSS was analogous to the one of the original Italian version (Raffagnino & Matera, 2015). We believe that these results support our hypothesis that relationship satisfaction as measured by the Sp-DFRSS may be conceptualized in terms of the two correlated factors, namely dyadic and familial. As in Study 1, the reliability of the two dimensions was appropriate given the high levels of Cronbach’s alphas. Again, the internal consistency obtained in our Spanish sample was very similar to the one found in Italy (Raffagnino & Matera, 2015). Through this Study 2 we further confirmed the good convergent and divergent validity of the Sp-DFRSS. As expected, a significant association between anxiety, avoidance, and relationship satisfaction was found (Li & Chan, 2012). Finally, as hypothesized, relationship satisfaction was linked not only to positive, but also to negative affect, which is congruent with previous research conducted in Spain (Molero et al., 2017). Overall, these findings show that both the dyadic and familial subscales of the Sp-DFRSS can predict different components of subjective well-being.

While in Study 1 and 2 relationship satisfaction was examined using individuals, through the Study 3 we analyzed relationship satisfaction and its link with psychological well-being among both members of cohabitant couples with children. Even when well-being was conceptualized in a more complex way, including different dimensions that are related to growth and human fulfillment, a significant association between relationship satisfaction and psychological well-being emerged, which is congruent with previous research conducted in Spain (Alonso-Ferres et al., 2019). Notably, the familial and dyadic dimensions contributed to psychological well-being in a peculiar and specific way, which confirmed the importance of distinguishing these different dimensions of relationship satisfaction.

Contrary to previous findings, significant gender differences did not emerge for our measure of relationship satisfaction. While in general women report being more dissatisfied with their marriage than men (e.g., Schumm et al., 1998), our couple members in Study 3 appeared to be equally satisfied with both the dyadic and the familial dimensions of relationship satisfaction.

Based on these findings, the Sp-DFRSS appears to be a useful instrument for measuring the extent to which Spanish-speaking couples are satisfied with their romantic relationship. According to the consistent results obtained through three independent studies, the Sp-DFRSS can be considered a valid and reliable instrument that can be successfully used in Spanish-speaking countries.

Limitations

In spite of the solid findings obtained, there are some limitations to the present research that should be considered. Firstly, the ratio of women/men of our samples in Study 1 and 2 was a little bit unbalanced (around 75% of women on both studies). However, Study 3 used a fully balanced sample with respect to gender. Secondly, all the data were collected through online procedures. Some researchers have expressed concern about web-based studies, but following expert recommendations, as we did, these problems may be overcome (for a review, see Reips, 2021).

Future research

We believe that cross-cultural studies are needed to demonstrate the applicability of measures aimed at assessing relationship satisfaction. For this reason, it is suggested that future studies might adapt the Sp-DFRSS to further sociocultural contexts (e.g., South America).

Current research has begun to expand beyond its historical focus on heterosexual relationships to include more diverse types of couples. In Spain, same-sex marriage has been legal since 2005, including the right of adoption by same-sex couples (Platero, 2007). For this reason, we believe it would be especially interesting to measure dyadic and familial dimensions of relationship satisfaction in same-sex couples.

Practical implications

Since its inception, relationship research has been motivated by the desire to resolve family issues because of the relevant effects of divorce for both parents and children. For example, high rates of divorce have been consistently associated with negative well-being consequences for adults following separation (for a review, see Bottom, 2013) and children of divorced parents scored significantly lower on measures of academic achievement, psychological adjustment, and social development (for a meta-analysis, see Amato, 2001). Although the DFRSS was primarily developed for research purposes, we believe this scale might be a useful tool also in clinical settings. We suggest that in couples therapy the level of agreement between spouses, regarding their relationship satisfaction, may be an important element to address.

Conclusion

This research provides evidence that the Sp-DFRSS is an appropriate tool for measuring the dyadic and familial dimensions of relationship satisfaction with Spanish speakers. The present study highlights only marginal differences between the Italian and the Spanish versions of the DFRSS, suggesting that this scale can capture relationship satisfaction in different European countries. As hypothesized, in Spain, like in Italy, dyadic and familial aspects of relationship satisfaction appeared to be clearly distinct.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Agus, M., Puddu, L., & Raffagnino, R. (2021). Exploring the similarity of partners’ love styles and their relationships with marital satisfaction: A dyadic approach. SAGE Open, 11(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211040785

Alonso-Arbiol, I., Balluerka, N., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). A spanish version of the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) adult attachment questionnaire. Personal Relationships, 14(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2006.00141.x

Alonso-Ferres, M., Valor-Segura, I., & Expósito, F. (2019). Couple conflict-facing responses from a gender perspective: Emotional intelligence as a differential pattern. Psychosocial Intervention, 28(3), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a9

Amato, P. R. (2001). Children of divorce in the 1990s: An update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(3), 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.15.3.355

Amato, P. R., Booth, A., Johnson, D. R., & Rogers, S. J. (2007). Alone together: How marriage in America is changing. Harvard University Press.

Bottom, T. E. (2013). The well-being of divorced fathers: A review and suggestions for future research. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 54(3), 214–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2013.773802

Bowlby, J. (1977). The making and breaking of affectional bonds: 1. Aetiology and psychopathology in the light of attachment theory. British Journal of Psychiatry, 130(3), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.130.3.201

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson, & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). Guilford.

Buss, D. H. (1995). Psychological sex differences: Origins through sexual selection. American Psychologist, 50(3), 164–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.50.3.164

Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. (2017). Barómetro 2017 [2017 Barometer]. Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Diamond, L. M., Fagundes, C. P., & Butterworth, M. R. (2010). Intimate relationships across the life span. In M. E. Lamb, A. M. Freund, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of life-span development (2 vol., pp. 379–433). Wiley.

Díaz, D., Rodríguez-Carvajal, R., Blanco, A., Moreno-Jiménez, B., Gallardo, I., Valle, C., & van Dierendonck, D. (2006). Spanish adaptation of the Psychological Well-Being Scales. Psicothema, 18(3), 572–577.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34

Eberhard, D. M., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (2019). Summary by language size. Ethnologue. SIL International.

Eurostat (2017). Marriage and divorce statistics. Eurostat.

Fraley, R. C., Brumbaugh, C. C., & Marks, M. J. (2005). The evolution and function of adult attachment: A comparative and phylogenetic analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(5), 731–746. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.5.751

Fraley, R. C., & Shaver, P. R. (2000). Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Review of General Psychology, 4(2), 132–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.4.2.132

Gere, J., & MacDonald, G. (2012). Assessing relationship quality across cultures: An examination of measurement equivalence. Personal Relationships, 20(3), 422–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12001

Graham, J. M., Diebels, K. J., & Barnow, Z. B. (2011). The reliability of relationship satisfaction: A reliability generalization meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022441

Harzing, A. W. (2006). Response styles in cross-national survey research: A 26-country study. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 6(2), 243–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595806066332

Hendrick, S. S. (1988). A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.2307/352430

Hernández, A., Hidalgo, M. D., Hambleton, R. K., & Gómez-Benito, J. (2020). International Test Commission guidelines for test adaptation: A criterion checklist. Psicothema, 32(3), 390–398. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2019.306

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jiménez-Picón, N., Romero-Martín, M., Ramirez-Baena, L., Palomo-Lara, J. C., & Gómez-Salgado, J. (2021). Systematic review of the relationship between couple dyadic adjustment and family health. Children (Basel Switzerland), 8(6), 491. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060491

Kamp Dush, C. M., Taylor, M. G., & Kroeger, R. A. (2008). Marital happiness and psychological well-being across the life course. Family Relations, 57(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00495.x

Keizer, R. (2014). Relationship satisfaction. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research (pp. 5437–5443). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2455

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Press.

Li, T., & Chan, D. (2012). How anxious and avoidant attachment affect romantic relationship quality differently: A meta-analytic review. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(4), 406–419. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1842

Locke, H. J., & Wallace, K. M. (1959). Short marital adjustment prediction tests: Their reliability and validity. Marriage and Family Living, 21, 251–255. https://doi.org/10.2307/348022

Lorenzo-Seva, U., & Ferrando, P. J. (2006). FACTOR: A computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model. Behavioral Research Methods, 38(1), 88–91. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192753

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2013). Adult attachment and happiness: Individual differences in the experience and consequences of positive emotions. In S. A. David, I. Boniwell, & A. Conley Ayers (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 834–846). Oxford University Press.

Molero, F., Shaver, P., Fernández, I., Alonso-Arbiol, I., & Recio, P. (2016). Long-term partners’ relationship satisfaction and their perceptions of each other’s attachment insecurities. Personal Relationships, 23(1), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12117

Molero, F., Shaver, P., Fernández, I., & Recio, P. (2017). Attachment insecurities, life satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction from a dyadic perspective: The role of positive and negative affect. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47(3), 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2276

Norton, R. (1983). Measuring marital quality: A critical look at the dependent variable. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45(1), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.2307/351302

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with Life Scale. Psychological Assessment, 5(2), 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164

Platero, R. (2007). Love and the state: Gay marriage in Spain. Feminist Legal Studies, 15(3), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10691-007-9064-z

Raffagnino, R., & Matera, C. (2015). Assessing relationship satisfaction: Development and validation of the dyadic-familial relationship satisfaction scale. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 14(4), 322–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332691.2014.975305

Reips, U. D. (2021). Web-based research in psychology: A review. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 229(4), 198–213. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000475

Roberson, P. N. E., Lenger, K. A., Norona, J. C., & Spencer, B. O. (2018). A longitudinal examination of the directional effects between relationship quality and well-being for a national sample of U.S. men and women. Sex Roles, 78(2), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0777-4

Ruffieux, M., Nussbeck, F. W., & Bodenmann, G. (2014). Long-term prediction of relationship satisfaction and stability by stress, coping, communication, and well-being. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 55(6), 485–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2014.931767

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Sandín, B., Chorot, P., Lostao, L., Joiner, T. E., Santed, M. A., & Valiente, R. (1999). The PANAS scales of positive and negative affect: Factor analytic validation and cross-cultural convergence. Psicothema, 11(1), 37–51.

Saxbe, D., & Repetti, R. L. (2010). For better or worse? Coregulation of couples’ cortisol levels and mood states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(1), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016959

Schudlich, T. D., Papp, L. M., & Cummings, E. M. (2011). Relations between spouses’ depressive symptoms and marital conflict: A longitudinal investigation of the role of conflict resolution styles. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(4), 531–540. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024216

Schumm, W. A., Nichols, C. W., Schectman, K. L., & Grigsby, C. C. (1983). Characteristics of responses to the Kansas Marital satisfaction scale by a sample of 84 married mothers. Psychological Reports, 53(2), 567–572. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1983.53.2.567

Schumm, W. R., Webb, F. J., & Bollman, S. R. (1998). Gender and marital satisfaction: Data from the National Survey of families and households. Psychological Report, 83(1), 319–327. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.83.1.319

Spanier, G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/350547

Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B., & Oishi, S. (2008). Being good by doing good: Daily eudaimonic activity and well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(1), 22–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.03.004

Vazquez, C., Duque, A., & Hervas, G. (2013). Satisfaction with Life Scale in a representative sample of spanish adults: Validation and normative data. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 16, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2013.82

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank to all the students that collaborated in our project.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. AM received a travel grant of the European Association of Social Psychology (EASP) Association to visit CM at Florence University. The funding organization had no further role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by AM. Analyses were performed by PR. The first draft of the manuscript was written by AM and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Approval was granted by the UNED's Ethical Committee.

Consent to participate

Online informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Magallares, A., Matera, C., Recio, P. et al. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Dyadic-Familial Relationship Satisfaction Scale. Curr Psychol 43, 3368–3380 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04603-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04603-3