Abstract

This research aimed to explore the direct and indirect effects of students’ school engagement, school climate and parenting practices on youth’s externalizing behaviors. A quantitative methodology with a sample of 183 Portuguese students, aged between 11 and 16 years old, was used. The main results suggested negative associations between externalizing behaviors and higher levels of school engagement and positive school climate. Poor parental supervision, inconsistent discipline and corporal punishment were positively related with externalizing behaviors, contrary to parental involvement and positive parenting that were associated with lower levels of externalizing behaviors. However, negative parenting practices were associated with lower levels of school engagement. Additionally, the results indicated that parenting practices might influence youth’s externalizing behaviors through school engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent decades, children and youth externalizing behaviors have been considered a priority issue and perceived as a major public health concern (Hann, 2002). Thus, the need for detailed and rigorous studies of the risk factors underlying the onset of these behaviors and the protective factors that might help preventing them have become mandatory (Liu, 2004). Usually, externalizing behaviors are understood as behaviors that are overt, that cause disruption, and that frequently involve the breaking of social norms, property destruction or harm towards others. Children who exhibit persistently higher levels of externalizing behaviors early in their lives are at greater risk of developing behaviors such as lying, bullying, and fighting in middle childhood, and more serious behaviors such as cruelty to animals, vandalism, and aggressive criminal behaviors, in adolescence (Keil & Price, 2006; Picoito et al., 2021). Additionally, it is also known that externalizing behaviors may escalate during adolescence, when peer influences might enhance antisocial behaviors, such as vandalism, theft, assault, substance use, and, in some cases, gang involvement and drug dealing (Hann, 2002; Loeber et al., 1993). Several studies (e.g., Farrington, 2007; Farrington & Welsh, 2007; Moffit, 1993) and criminological theories (e.g., Hirschi, 1969; Sampson & Laub, 1995; Thornberry, 1987), have sought to identify the main risk factors for antisocial and delinquent behaviors. School attachment or engagement and parenting practices are among the most frequently mentioned risk factors in the etiology of youth problems. Problem behaviors have been linked to a rupture in the individual’s social bonds to normative and institutional contexts, such as family and school. It is also important to recognize the indirect links between these bonds, in other words, how school and family bonds are related.

Thus, considering the above-mentioned rationale, this study aimed to explore the influence that school factors such as school engagement and school climate, and family factors such as parental supervision, affection, and punishment have on youth externalizing behaviors. Furthermore, considering the empirical evidence regarding the direct and indirect associations between school, family and children and youth behavioral problems, this study also sought to analyze how school engagement and parenting practices are interrelated in the explanation of children and youth’s externalizing behaviors.

Theoretical background

School factors

As children grow older and enter adolescence, they tend to spend less and less time with their parents and more time in school and with their peers, which makes school variables central features for understanding and, subsequently, preventing the development of maladaptive behaviors (Kasen et al., 1998). Attending school can be perceived as a conventional activity, where normative models are promoted and where tools for a successful future are provided, which means it can act as a protective factor regarding the development of children and youth problem behaviors (Christle et al., 2005; Farrington, 2007; Hirschfield & Gasper, 2011). Students’ engagement in school and a positive school climate are two potential protective factors for youth externalizing behaviors. In contrast, according to Hirschi (1969), individuals with lower school engagement may have more difficulties to internalize conventional norms, which can lead to problematic behaviors in school settings that are particularly dangerous for academic development, as they result in disciplinary actions that ultimately drive children and youth away from the classroom (Mihalec-Adkins & Cooley, 2020).

School engagement is a multifaceted construct that includes behavioral, affective, and cognitive dimensions (Jimerson et al., 2003; Wang & Fredricks, 2014) and refers to the thoughts, attitudes, and emotions that children and youth have towards school and learning (Cole et al., 2013). Behavioral engagement includes the participation in school-related activities, both academic and extracurricular (Wang & Fredricks, 2014). This type of engagement is related to the interactions that occur both inside the classroom and in the rest of the school context, as well as in out-of-school settings (Furlong et al., 2003). Affective engagement relates to the fondness felt by students for their teachers, colleagues and school staff and the concern about their desires and expectations towards them (Jimerson et al., 2003). That is, this type of engagement is based on positive emotional dispositions and affective responses concerning educational practices and processes, as well as teachers and school staff (Skinner & Belmont, 1993). Finally, cognitive engagement is related to the mental effort that individuals invest - or the motivation they feel to do so - in academic activities, their self-regulation and their willingness to improve (Reschly & Christenson, 2012). Such engagement can be expressed through flexibility in problem solving, a preference for hard work and coping mechanisms to handle possible failure (Hirschfield & Gasper, 2011). Furthermore, cognitive engagement is also reflected in the importance placed on learning and on school as a way of achieving one’s aspirations for the future (Reschly & Christenson, 2012).

Considering this, several studies have explored the influence of school engagement on youth misconduct. For example, Hirschfield and Gasper (2011) found that affective engagement reduces disruptive behaviors at school by strengthening the relationships between students and school staff, and by driving the youth to seek out similar peers. Furthermore, higher levels of affective engagement may lead individuals to weight their actions according to the level of approval they feel that they will receive (Hirschi, 1969). That is, when youth are concerned about the expectations towards them (e.g., from their teachers), they are less likely to act in a way that might disappoint them. Also, it was found that behavioral engagement may prevent antisocial and delinquent behaviors because time spent on school activities, such as doing homework, studying, or participating in extracurricular activities, reduces the time available for deviant activities (Li & Lerner, 2011). Furthermore, Gardner et al. (2008) showed that higher levels of cognitive engagement is related to self-regulation, specifically to the individual’s ability to systematize and create strategies that facilitate learning. This self-regulation might help youth to avoid engaging in deviant activities by making them evade risky situations and by shaping their reactions to adverse environments. Thus, higher levels in all three dimensions of school engagement can create a motivational context that shapes youths’ ability to cope with difficulties and obstacles in school, overcome potential failures and constructively re-enter challenging school tasks, preventing the emergence and maintenance of externalizing behaviors (Wang & Fredricks, 2014).

School climate can also play an important role in influencing youth’s behaviors. School climate is related to the quality and atmosphere of the school. In other words, it concerns the school community experiences and it is translated into the norms, goals, values, interpersonal relationships, teaching and learning practices, and organizational structures that define a specific school setting (Cohen et al., 2009). Analyzing school climate means analyzing the quality of teaching and learning, personal interactions, school organization and the institutional and structural features of the school environment (Wang & Degol, 2016). A positive school climate is found when students, teachers, and school staff feel socially, emotionally, and physically safe (Cohen et al., 2009).

Like school engagement, school climate is also a multidimensional construct, usually understood as the result of four dimensions, namely: academic climate, community, safety, and institutional environment (Wang & Degol, 2016). Academic climate refers to the ways teaching, learning, leadership, and professional development are promoted (Stefanou et al., 2004). Community is related to the quality of the interactions among members of the academic community (Gottfredson, 2000). The safety dimension concerns to the physical and emotional safety provided by the school and its members, as well as the level of order and discipline present in the school setting (Morrison et al., 1994). At last, the institutional environment encompasses the level of environment adequacy (e.g., good lighting, good acoustics, adequate temperature, open spaces without hiding spots), the building infrastructures and its maintenance, as well as the accessibility and allocation of educational resources (Wang & Degol, 2016).

Regarding the relationship between school climate on externalizing behaviors, a positive academic climate has been found to be an excellent way of directing focus and energy of students with antisocial problems towards developing social skills and keeping them away from deviant peers (McEvoy & Welker, 2000). Positive school climate has been linked to less drug use, fewer self-reports of psychiatric problems, and better psychological wellbeing among students (Thapa et al., 2013). A positive school climate also predicts better social skills and school adjustment (Esposito, 1999). When teaching practices are perceived as prioritizing students’ understanding and not just the grades they earn, the levels of aggression and disruptive behavior also tend to decrease (Kaplan et al., 2002). When students perceive school as a place with high cohesion and connectedness, the risk of serious bullying situations decreases, as do violent behaviors (Brookmeyer et al., 2006). Furthermore, students feel more willing to intervene or report on others deviant behaviors when they perceive the school environment to have a strong sense of cohesion and belonging (Syvertsen et al., 2009). Moreover, positive relationships between teachers, principals, and students have been associated with a decrease in behavioral problems (Wang et al., 2010), just as positive peer relationships are associated with a decrease in levels of aggression, victimization, and other behavioral problems (Elsaesser et al., 2013).

Similarly, the safety dimension is an important determinant of students’ experiences of violence and bullying. In schools without supportive and safe norms, structures, and relationships, students are more likely to experience violence, peer victimization, and punitive disciplinary actions, often accompanied by high levels of truancy and lower academic achievement (Astor et al., 2010; Elsaesser et al., 2013) showed that students who perceive problems in school safety are more likely to engage in relational aggression, as well as becoming victims of it. In contrast, students attending schools with higher levels of consistency in discipline reported less bullying and victimization behaviors (Gottfredson et al., 2005). Additionally, the schools whose rules are perceived as fair and clear have lower rates of juvenile delinquency and victimization. Studies have also shown that school connectedness is associated with violence prevention (Karcher, 2002a, b; Skiba et al., 2004), student satisfaction, and conduct problems (Loukas et al., 2006). Moreover, school climate research has indicated that school connectedness is a protective factor against risky sexual violence and drug use behaviors (Catalano et al., 2004; Kirby, 2001). Finally, youth who perceive that peer conflicts at their school are resolved more peacefully and less aggressively tend to engage in less risky behaviors (LaRusso & Selman, 2011). In short, empirical evidence highlights the importance of promoting a positive school climate to prevent and mitigate the occurrence of aggressive and delinquent behaviors.

Therefore, based on previous literature on this subject, comprising both conceptual discussions and empirical studies, it is relatively easy to understand that specific school variables, such as school climate and involvement, play an important role in shaping the conducts of children and youth. Even though school is first and foremost designed to enhance children and youth educational and social skills, recent research shows that a significant amount of behavioral problems often arise in this context (Gottfredson, 2012). This reinforces the need for research studies, such as this one, in order to establish a scientific basis that allow the development of strategies focusing on the promotion of education quality, school organization, caring and supporting environments, clarity and fairness of rules, positive relations between peers and school staff, and youth commitment and involvement towards school and its activities, as a way of preventing and reducing maladaptive behaviors (Aldridge et al., 2018; Prior & Paris, 2005; Benard, 1991; Weerman et al., 2007).

Parenting practices

Family factors, including parenting practices (e.g., low levels of warmth and attachment, poor supervision, harsh punishment and inconsistent discipline), have also been identified as important risk factors for externalizing behaviors in children and youth (e.g., Farrington, 2007; McCord, 1997; Thornberry, 2005).

According to Grusec and Davidov (2015), parental warmth, comprising parental behaviors of affection, emotional support and parental sensitivity, is crucial to promote children’s self-regulation, empathy and parental attachment. Furthermore, higher levels of parental attachment might encourage a greater acceptance of parental expectations and social norms, also contributing to children and youth’s involvement in conventional activities (Gault-Sherman, 2012; Hirschi, 1969). In contrast, parental rejection and lower levels of affection are associated with more hostile and coercive interactions between parents and children, which, in turn, can enhance association with deviant peers and antisocial behaviors (Farrington, 2007; McKee et al., 2008). For example, McCord’s (1997) study revealed that parental warmth can have a protective effect on the negative consequences of physical punishment. More specifically, this study showed that 51% of boys with more punitive and cold mothers during childhood were convicted later in the life course, compared with 21% of boys convicted with mothers who, despite using physical punishment, also showed a relationship of affection and closeness with the child. The meta-analysis conducted by Hoeve et al. (2009) also revealed that parental rejection and hostility were important predictors of future delinquent behavior. Finally, results from the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study suggested that low parental involvement (the absence of a father figure in performing leisure activities with the child) doubled the risk of future conviction, as well as, predicted delinquent behavior after 21 years of age (Farrington & Welsh, 2007).

Poor parental control, including poor supervision, has also been systematically linked with a greater likelihood of externalizing behaviors during childhood and adolescence (e.g., Dishion et al., 2004; Farrington & Welsh, 2007; Loeber and Stouthamer-Loeber, 1986). Parental supervision refers to the degree of monitoring by parents of the children’s daily life, such as asking for information about their routine activities and peers (Merrin et al., 2019). In this context, the literature suggests that parents who supervise their children have a greater ability to identify and minimize negative peer influences and encourage prosocial behaviors (Farrington, 2007; Fischer, 1983; Grusec & Davidov, 2015; Smith & Stern, 1997). For example, in the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study poor parental supervision during childhood emerged as the most robust predictor of violent crime and property crime at age 45 (McCord, 1997). The meta-analysis conducted by Loeber and Stouthamer-Loeber (1986) also confirmed the importance of this parenting practice, suggesting that the relationship between poor supervision and delinquency is more significant in relation to official delinquency when compared to self-reported delinquency. In a more recent meta-analysis, Hoeve et al. (2009) found a robust negative relationship between active supervisory behaviors and antisocial behavior.

Finally, punitive and inconsistent discipline has also been associated to externalizing behaviors in children and youth (e.g., Farrington & Welsh, 2007; McCord, 1997; Moffitt, 1993; Santos et al., 2023). According to Thornberry (2005), coercive and severe disciplinary practices can contribute to a more hostile family environment in which the child might learn aggressive and antisocial behavioral patterns. In turn, inconsistent discipline can promote an unpredictable environment for the child, in which it is more difficult to predict the negative consequences of inappropriate behaviors (Van Gelder et al., 2018). Regarding the empirical evidence in this domain, longitudinal research like The Pittsburgh Youth Study suggested that physical punishment predicts future delinquency and that these effects can vary according to ethnicity or race: 21% of Caucasian individuals who were physically punished during childhood by their mothers became more violent adults, compared with 32% of African-American subjects who had similar results (Farrington et al., 2003). Similarly, Loeber et al. (1995) found that the use of inconsistent discipline during childhood (7–12 years old) predicted antisocial behaviors 6 years later. Lastly, Gershoff (2002) meta-analysis also showed that, in 88 studies, corporal punishment was significantly associated with multiple negative behaviors and experiences in childhood, including physical abuse, externalizing and delinquent behaviors.

Thus, even though school plays an important role in the positive or negative development and later social adjustment of children and youth, previous studies have also highlighted the important part that the family, as a primary socialization context, play in molding their behaviors. In fact, there is a robust body of evidence demonstrating that factors such as parent-child interactions, parenting strategies (e.g., discipline, monitoring, involvement, attachment) or the family environment might exert a significant influence over the behaviors and attitudes displayed by children and youth in multiple settings (Wong et al., 2010; Hoeve et al., 2012; Apel & Kaukinen, 2008; Price & Kunz, 2003; Leiber, Mack, & Featherstone, 2009; Petts, 2009; Santos et al., 2023). Therefore, the relevance that the knowledge on these factors represents for the improvement of preventive and interventive efforts justifies the need for continuous research on this subject, assessing different populations and exploring the complex relations that family related variables, such as parenting practices, exert in the development of behavioral problems.

Indirect and interactive effects between school and family factors

In the past, there was a tendency to focus on either school or family factors to explain youth problem behaviors, which tends to overshadow important interactions between those factors and their influence on development of children and youth externalizing behaviors. In fact, even though parent and school bonds have been largely studied, independently of each other, much less is known about how these elements interact to influence the children or youth’s behaviors, which is the main gap that the current study seeks to address. This is the major contribution it aims to give: contribute to a deeper analysis of school and family factors and provide more understanding about the joint contribution of this factors on youth externalizing behaviors. We draw from relevant theories (Hirschi, 1969; Sampson & Laub, 1995; Thornberry, 1987) to consider that positive parenting practices may reduce externalizing behaviors by increasing school bonds, specifically school engagement.

Although there is not yet an extensive body of research on this topic, several classic theories are very useful and informative. For example, Sampson and Laub’s (1995) age-graded social control theory highlights that desistance from antisocial pathways happens when ties to conventional institutions, such as schools, are strong and cumulative. In addition, positive parenting practices may reduce misbehaviors among aggressive children by promoting school bonds. Sampson and Laub (1995, p. 246) overtly note the connection between family and school dynamics proposing that “family and school processes of social control provide the key causal explanation of delinquency”. Thornberry’s (1987) interactional theory also presents a similar argument. This theory is most widely known for its focus on the reciprocity that lies between crime and its causes. As part of its rationale, it emphasizes that family characteristics early in the life course have indirect effects on adolescent delinquency and are mediated by other factors, such as school ties. Considered as a whole, Thornberry’s theory seizes an integrated approach that perceives parent-child relationships as a continuum due to how they may impact adolescent engagement with groups and institutions beyond family context, including what occurs at school and with peers. Thornberry and his counterparts (1991) reached important conclusions on this topic when they tested the interactional theory in the Rochester Youth Development Study. Among other results, they found that while attachment to parents had an immediate effect on commitment to school, commitment to school did not exert a significant lagged or direct effect on attachment to parents. Additionally, commitment to school and delinquent behavior were engaged in a reciprocally reinforcing causal relationship across time: low commitment increased delinquency and, in turn, delinquency reduced commitment to school. They also found that the influence of parenting practices on delinquency diminished significantly over time, as the children grew older.

These theories provided an important foundation to a more recent trend in which mediation and moderation effects between school and family factors are studied. Using a sample of 6,397 teenagers, Brookmeyer and colleagues (2006), sought to understand how family and school environments interact and how they are related to youth aggressive behaviors. Specifically, they assessed attachment to school and parents, school climate, and parental involvement, trying to understand whether these variables acted independently or together in reducing the risk of aggressive behavior. The results indicated a positive influence between school and parental attachment in mitigating the effects of violence exposure. Particularly, higher levels of school and parental attachment have been shown to reduce the effects of exposure to violence by reducing the likelihood of future aggressive behaviors. A possible explanation for this result is that when individuals feel attached to school, they are more likely to talk with their teachers about experiences of violence, which may lead to better coping skills and decreased violent behavior (Resnick et al., 1997). This study also suggested that school-level indexes of school climate acted as a protective factor for student violent behavior, which means, adolescents who attended schools with higher levels of positive school climate engaged in fewer types of violent behaviors across time. Attachment to parents and parental involvement have also been associated with reduced violent behaviors, just as highly supportive parenting styles have been shown to attenuate the link between exposure to violence and those behaviors. Thus, when attachment levels are high at both school and family settings, an individual is less likely to engage in delinquent acts, even in the presence of risk factors such as exposure to violence (Brookmeyer et al., 2006).

Rovis et al. (2016) studied the influences of school engagement on risk behaviors and how the differences found were related to family environment, specifically the quality of relationships between parents and children. To do so, they used a sample of 1,519 youth attending 9th, 10th and 11th grades, in different schools. The researchers tested a particularly interesting hypothesis: students from adverse family environments, but with higher levels of school bonding manifest significantly less risky behaviors than students from similar family environments who attend schools with lower levels of school bonding. The findings demonstrated that children coming from more favorable family environments were usually less prone to risky behaviors and would do even better if they attended schools with better levels of school bonding. This finding was also true for students coming from an adverse family environment, who exhibit less risky behaviors if they were from schools with higher levels of school engagement. Therefore, school bonding or engagement might act as a protective factor for those exposed to risks from other domains, such as family adversity.

In another research, Sabatine and colleagues (2017) examined the interactive associations between parental involvement, school engagement and juvenile delinquency using a sample of 945 adolescents, following them between the 6th and 9th grades. The researchers concluded that school engagement and parental involvement played an important role in the prevention of juvenile delinquency. Although the overall sample saw their rate of deviant behavior increasing over time, the results indicated that youth with higher levels of both parental involvement and school engagement reported the smallest increasing in delinquent behaviors. Thus, it was possible to conclude that school engagement had a complementary effect on the relationship between parental involvement and delinquency reduction. In other words, higher levels of parental involvement were shown to be more strongly associated with reducing delinquency when levels of school engagement were also high: students with the lowest levels of delinquency were those with the highest levels of both parental involvement and school engagement. Thus, school engagement was shown to have an additional effect on the relationship between parental involvement and delinquency. According to the authors, positive attachments with normative adults, both at school and at home, matter for the internalization of pro-social norms that prevent the occurrence of future deviant behaviors. Thus, the jointly considered, higher levels of school engagement and parental involvement are a key protective mechanism against juvenile delinquency (Sabatine et al., 2017). Hence, considering the clues provided by these and other studies, the importance of studying school and family factors as essential elements in the explanation of disruptive behaviors becomes clear, especially when considering how they operate together.

In summary, the reviewed literature suggests the existence of an indirect relationship between family and the development of externalizing behaviors in childhood and adolescence, with the school context emerging as a crucial mechanism in explaining the apparent complex interplay between those variables (e.g. Brookmeyer et al., 2006; Sabatine et al., 2017). More specifically, previous studies have demonstrated the relevant role that positive parenting, as well as several aspects related to the school environment, play as protective factors for the development of children and youth’s behavioral problems. Based on this framework, and considering the clues provided by these and other studies reviewed throughout this paper, this study aims to explore the mechanisms by which parental strategies influence children and youth’s externalizing behaviors, thus contributing to the literature focused on understanding the interrelation between potential risk and protective factors for conduct problems.

Current study

In light with this rationale, this pilot exploratory cross-sectional research seeks to explore the direct and indirect influence of school engagement, school climate and parenting practices on youth externalizing behaviors. Specifically, it intended to investigate multiple dimensions of school and family variables related to the development of externalizing behaviors and analyze direct and indirect effects between parenting practices, school engagement and externalizing behaviors. By The choice of analyzing several dimensions of each one of these constructs was decided based on the need to conduct an extensive and profound analysis of the issue in study. Family and school are complex networks that can be unraveled in different domains, all of which deserve to be studied. The literature indicates that school engagement promotes a motivational context that outlines youths’ ability to cope with adversities and prevents the emergence of externalizing behaviors (Wang & Fredricks, 2014). So, we hypothesized that higher levels of affective, behavioral, and cognitive school engagement will be negatively related to externalizing behaviors. The school setting is an important microsystem in adolescents’ life, which can thereby act as a learning context for socioemotional and relational skills, in addition to its academic and cognitive educational aims (Franco et al., 2022). Therefore, based on documented links between school climate and youth problematic behaviors, we hypothesized that students’ positive perceptions of school climate will be negatively associated with externalizing behaviors. Also, considering at parenting factors, a proper balance between responsiveness – meaning emotional warmth, support and fostering of individuality – and demandingness – referring to the ability to draw boundaries and monitor the child’s behavior – is linked to lower levels of antisocial behavior and conduct disorders (Marcone et al., 2020). Thus, we hypothesized that positive parenting and parental involvement will be negatively related to externalizing behaviors, while poor parental supervision, inconsistent discipline and corporal punishment will be positively related to higher levels of externalizing behaviors. The literature reviewed has indicated that there is a minor probability of deviant behaviors when ties to conventional institutions, such as family and schools are cumulative. Besides that, positive parenting practices may reduce misbehaviors among aggressive children by promoting school bonds (Sampson & Laub, 1995; Thornberry, 1987). Thus, two hypotheses were drawn. First, positive parenting and parental involvement will be positively related to higher levels of school engagement, while poor parental supervision, inconsistent discipline and corporal punishment will be negatively related to higher levels of school engagement. Second, we hypothesized that school engagement will mediate the relationship between parenting practices and externalizing behaviors. We believe that positive parenting practices play an important role promoting school engagement, which should lead to lower externalizing behaviors, in contrast with negative parenting practices.

Method

Participants

The study was undertaken with a non-clinical, convenience sample of 183 participants, attending 7th (n = 54) 8th (n = 59) and 9th (n = 70) grades of middle school. All participants were non-referred children and youth, attending school in the North of Portugal. The sample was composed of 54% male participants (n = 98) and the vast majority was Caucasian (93%). The participating children and youth aged between 11 and 16 years, with an average age of 13.6 years (SD = 1.10).

Procedures

The data were collected during 2021. The participating school was selected based on the school years administrated as well as the availability to participate in the study. In order to ensure school’s participation, the researchers contacted the principal so that the consent for the development of the research was achieved. Furthermore, this contact allowed the joint selection of the specific classes that would be sampled, considering the eligibility criteria defined for the current study, namely the participant’s age and grade. Students presenting special education needs were not considered eligible for participation in the current study.

This procedure also sought to outline the steps necessary to obtain the participants’ legal guardians’ consent and authorization for participation in the research, considering that all the participating children and youth were under-aged. Only after gathering all the consents, the data gathering begun. Moreover, it should also be mentioned that the University of Porto - Faculty of Law’s Ethical Committee approved the development of the current study.

All the participants completed paper and pencil self-report measures, after the researchers provide them with details of the study and instructions on how to complete the forms. The questionnaires were completed in the classroom where one researcher was present to clarify any semantic doubts that could appear while completing the forms. It should be noted, however, that no questions were raised while the participants were completing the questionnaires.

Measures

Externalizing behavior

- Considering the age group defined for this study, the externalizing behaviors were assessed using an Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment tool – the Youth Self-Report (YSR) broadband externalizing scale, which assesses behavioral problems and integrates both rule breaking and aggressive behavior syndrome scales. YSR, is a self-report questionnaire, which was developed to be completed by children and youth, aged between 11 and 18 years old, and it constitutes a standardized screening measure that is extensively used to identify emotional, social and behavioral problems and social competencies in children and adolescents (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; Achenbach et al., 2008; Ivanova et al., 2007). All rated items refer to symptoms or problems experienced during the previous 6 months. For each syndrome scale, respondents are requested to report on the degree or frequency of each behavior described in the item on a scale of 0 = “not true”, 1 = “somewhat or sometimes true”, or 2 = “very true or often true”. The AEBA technical manual reports psychometric properties ranging from good to excellent (see Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001; Achenbach et al., 2008;). The instrument was translated into Portuguese and their reliability analysis revealed satisfactory results with α = 0.80.

Parenting practices

- Parenting practices were assessed using the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire – Child Version (APQ-C; Thulin et al., 2019). Adopting a self-report format, this questionnaire measures parenting practices perceived by children within the family (Frick et al., 1999; Thulin et al., 2019). This 51-item instrument is designed to assess five dimensions of parenting, considered relevant for the emergence and the intervention in children’s behavioral problems, namely: positive parenting, parental involvement, inconsistent discipline, poor supervision, and corporal punishment. It should be noted that, for most items in this questionnaire the children are asked to report on their parent’s practices without distinguishing between mother and father, the only exception being parental involvement, regarding which the respondent is requested to answer separately for each parent. Specifically, using a 5-point Likert scale, varying between 1 = “never” and 5 = “always”, the respondents are required to report to what extent do they consider the sentences describe their parents’ typical behaviors (Frick et al., 1999; Thulin et al., 2019). Higher scores in the positive parenting and parental involvement subscales indicate more suitable parenting practices, whereas higher scores in the remaining subscales suggest less adequate parental strategies (Thulin et al., 2019). This measure was translated and adapted for several languages and countries (e.g., Escribano et al., 2013; Graham & Weems, 2015; Nogueira et al., 2020; Shelton et al., 1996; Thulin et al., 2019), generally presenting good to excellent psychometric properties (Thulin et al., 2019), that were also observed in the current study: parental involvement (α = 0.89); positive parenting (α = 0.85); corporal punishment (α = 0.75); poor supervision (α = 0.67) and inconsistent discipline (α = 0.60).

School Climate

- the Portuguese version of the Delaware School Climate Survey – Student was used to assess school climate (Bear et al., 2011; Melo & Guerra, 2020). This 31-item self-reported questionnaire is composed of 6 subscales, including: teacher-student relations, student-student relations, student engagement school-wide, school safety, fairness of rules and bullying school-wide. All items are evaluated on a 4-point scale varying from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 4 = “strongly agree”. Item scores are then averaged to create a school climate total score, with higher scores indicating more positive school climates. This measure has been revealing good psychometric properties presenting α values ranging from α = 0.78 e α = 0.82 (Melo & Guerra, 2020). Considering the purposes of the current study, only four subscales were used, namely: teacher-student relations, student-student relations, school safety and fairness of rules. The reliability analysis revealed satisfactory results with α = 0.90 for the school climate total score, and values varying from α = 0.72 and α = 0.84 for the remaining subscales considered in this research.

School Engagement

- school engagement was measured using Students’ Engagement in School Four-dimensional Scale (SES-4DS; Veiga, 2008; Veiga et al., 2012; Veiga, 2013). This 20-item self-report measure was designed to assess student’s engagement in school, considering four dimensions of engagement: cognitive (information processing and management; planning and task execution), affective (school attachment; inclusion; feeling of belonging), behavioral (student’s behavior; participation in curricular and extracurricular activities) and personal agency (students as agent for positive actions and interventions in the classroom; Veiga, 2013). The respondents are asked to report on how they agree with the statements in each one of the above-mentioned subscales using a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = “totally disagrees” and 6 = “totally agrees”. Overall, higher scores indicate a higher engagement, the only exception being the items in the behavioral dimension, in which lower scores indicate higher engagement. The psychometric properties of this measure are considered good, with α values ranging from α = 0.87 e α = 0.70 (Silva et al., 2016; Veiga, 2013). Similar results were found in the current study, with the total engagement scale revealing a α value of 0.86 and the scores for each subscale ranging from α = 0.76 and α = 0.90.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and reliability analyses of the scales were used to assess the psychometric features of the sample. Pearson’s r correlations coefficients were used to explore the relationships between the variables under study. Subsequent data analysis was conducted to examine the direct and indirect effects of school climate, school engagement and parenting practices in externalizing behaviors. For that purpose, multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to identify significant predictors of externalizing behaviors. Furthermore, indirect pathways were tested using SPSS PROCESS 3.2 Macro (Hayes, 2018). The SPSS PROCESS Macro enables the estimation of the total effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, the direct effect of the independent variable on dependent variable controlling for the mediator, and the indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable through the mediator. In addition, the statistical tests provided by PROCESS are based on bootstrapping methods, an advantage when it comes to examine variables with non-normal distributions. Finally, PROCESS allows the estimation of the parameters of each equation independently, in contrast to the structural equation models that analyze all the equations introduced simultaneously, using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) (Hayes et al., 2017).

Results

Correlations between School and Family factors and externalizing behaviors

The correlations between the variables under study are presented on Table 1. As it was hypothesized, behavioral (r = − .374), affective (r = − .402), and cognitive (r = − .178) engagement and all dimensions of school climate (r-values ranging from − 0.361 to − 0.251) were negatively related to externalizing behaviors. Positive parenting (r = − .210) and parental involvement (r = − .327) were also negatively related to externalizing behaviors, while poor parental supervision (r = .288), inconsistent discipline (r = .359) and corporal punishment (r = .293) were positively related to externalizing behaviors.

Taking a more in-depth analysis on school and family factors relations, school engagement and all dimensions of school climate were positively related, presenting R-values that ranged from 0.335 (school engagement x peer relationships) to 0.497 (school engagement x teacher-student relationships). School engagement was also related with parenting practices, except for corporal punishment. The dimension of parenting with the strongest correlation with school engagement was parental involvement (r = .446), suggesting that the more involved parents are with their children, the greater school engagement will be, especially when it comes to cognitive dimension (r = .470). Positive parenting was also positively related with school engagement (r = .374). On the other hand, inconsistent discipline (r = − .337) and poor supervision (r = − .392) were negatively related with school engagement, particularly regarding poor supervision and behavioral school engagement (r = − .505). This means that the fourth hypothesis of the current study was only partially confirmed, since not all parenting practices were correlated with school engagement.

Direct and indirect effects between variables

The first column of Table 2 indicates the set of models regressed for the externalizing behaviors variable. The first partial model (model 1), that included parenting practices, explained about 33% (p < .001) of the variance of the dependent variable. Parental involvement (b = -2.05, p = .01), inconsistent discipline (b = 1.70, p = .01), poor supervision (b = 1.28, p = .08) and corporal punishment (b = 2.69, p < .01) significantly predicted externalizing behaviors. When school climate dimensions were added to the partial model (model 2), about 38% (p = .038) of the variance on externalizing behaviors was explained. Although parental involvement (b = -1.69, p = .02), inconsistent discipline (b = 1.58, p = .01) and corporal punishment (b = 2.36, p < .01) retained an influence on externalizing behaviors, poor supervision lost its influence on it. In turn, externalizing behaviors were explained by student-student relations (b = -1.95, p = .02). Also, when school engagement variables are added (model 3), the explained variance increases to about 44% (p = .013). In this final model, externalizing behaviors were explained by parental involvement (b = -1.71, p = .03), inconsistent discipline (b = 1.36, p = .03), corporal punishment (b = 2.03, p < .01), student-student relations (b = -2.03, p = .02) and behavioral school engagement (b = -1.73, p = .01). Corporal punishment and students’ relationships with their peers were the best predictors of the dependent variable, showing that individuals with parents who use corporal punishment and with weak relationships with other youth present higher levels of externalizing behaviors.

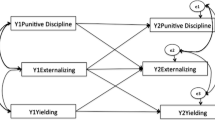

Mediation models were also tested to explore the last hypothesis posed and to understand the indirect effects of parenting practices on externalizing behaviors, specifically through their impact on school engagement (see Table 3). Specifically, we aimed to analyze whether school engagement mediates the relationship between parenting practices and externalizing behaviors. According to our results, parenting practices have an indirect effect on externalizing behaviors by reducing or increasing school engagement. Specifically, parental involvement (B = 42, p < .001) and positive parenting (B = 33, p < .001) may increase school engagement, leading to a decrease in externalizing behaviors. On the other hand, poor supervision (B = -40, p < .001), inconsistent discipline (B = -30, p < .001) and corporal punishment (B = -17, p = .028) may reduce school engagement, which might lead to higher levels of externalizing behaviors.

Discussion

The need for detailed and rigorous research on the risk and protective factors for externalizing behaviors, that might help preventing such behaviors, have become mandatory (Hann, 2002). Therefore, this study sought to contribute with interesting and solid findings on this topic. Specially, it aimed at exploring the direct and indirect associations between school and family factors and the developmental of children and youth’s externalizing behaviors. Specifically, it sought to analyze how school engagement and parenting practices are related in explaining those behaviors. Thus, the following hypotheses were tested: (1) higher levels of affective, behavioral, and cognitive school engagement will be negatively related to externalizing behaviors; (2) students’ positive perceptions of school climate will be negatively associated with externalizing behaviors; (3) positive parenting and parental involvement will be negatively related to externalizing behaviors, while poor parental supervision, inconsistent discipline and corporal punishment will be positively related to higher levels of externalizing behaviors; (4) positive parenting and parental involvement will be positively related to higher levels of school engagement, while poor parental supervision, inconsistent discipline and corporal punishment will be negatively related to higher levels of school engagement; and (5) school engagement will mediate the relationship between parenting practices and externalizing behaviors. The results driven from the analysis conducted lead to three main conclusions, namely: (i) school factors play an important role in reducing externalizing behaviors; (ii) parenting practices have a direct effect on school engagement and on externalizing behaviors; and (iii) parenting practices have an indirect effect on externalizing behaviors by promoting or reducing school engagement.

Regarding the first conclusion, the results suggested that there is a negative association between externalizing behaviors and positive perceptions about school climate and higher levels of school engagement, which is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Bender, 2012; Li & Lerner, 2011; Sandahl, 2016; Wang et al., 2010; Wang & Fredricks, 2014). Affective school engagement was the dimension that proved to be more strongly related to externalizing behaviors, which means that, in the current sample, the feelings of affection, joy, sympathy, belonging and attachment towards the school and school members are the crucial in preventing the development of such behaviors. When these feelings are present, the youth expect to achieve the expectations placed on them (Hirschi, 1969). Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that externalizing behaviors could be reduced when youth have an adequate school network in which they are emotionally involved (Gottfredson, 2000; Olivier et al., 2020), which might constitute a possible explanation for the results observed in the current research. In this study, the perception that individuals have on the relationship between teachers and students is the dimension of school climate more significantly associated with the decrease in externalizing behaviors. This result was also consistent with previous studies. For example, Wang and colleagues (2010) concluded that positive relationships between teachers and students are one of the most important school factors in reducing disruptive problems. This might indicate that the emotional support promoted by teachers is more effective than classroom discipline in preventing behavioral problems (Sandahl, 2016). Moreover, it also suggests that the emotional dimensions of school factors are the ones with the major impact in externalizing behaviors, which leads us to the crucial role that social bonds and the affective connection with normative individuals play in preventing externalizing behaviors (Hirschi, 1969; Liu, 2004).

The second major finding of the current study was that parenting practices have a direct effect on school engagement and on externalizing behaviors, corroborating the results from previous studies (e.g., Gault-Sherman, 2012; Liu, 2018; Stattin & Kerr, 2000). Parental involvement was the strongest correlate of school engagement. That is, for this sample, the existence of parents or caregivers who seek to engage positively with children and maintain an affective bond with them, may enhance their probability of positively engaging with school as well. This is in line with previous studies, such as the one from Hill and Wang (2015), who, through a longitudinal study concluded that parental involvement is an important predictor of school engagement, since it would provide children and youth with a foundation for promoting their sense of self-efficacy and self-confidence on their skills (Juang & Silbereisen, 2002). Furthermore, these results suggested that when parents are more involved with their children it might promote the development of a sense of competence that could result in a much healthier attachment to school (Hill & Wang, 2015).

In addition to parental involvement, inconsistent discipline and corporal punishment also emerged as significant predictors of youth’s externalizing behaviors. Consistent discipline can promote children and youth’s accountability for their actions and makes the consequences of their maladaptive behaviors more predictable (Halgunseth et al., 2013). In turn, inconsistent discipline creates an unpredictable environment, in which children’s behavior is neither modeled nor appropriately responded to. Moreover, this type of discipline is associated with the development of impulsive reactions and a preference for immediate rewards, which may culminate in the occurrence of externalizing behaviors (Van Gelder et al., 2018). Corporal punishment, a kind of severe discipline, is associated with the development of coercive family relationships and with the learning of antisocial behavioral patterns by children and youth (Thornberry, 2005). Additionally, this type of discipline fosters in children/youth the belief that their desires can be achieved through power and violence (McCord, 1997). Consequently, as our data also suggested, externalizing behaviors are also more likely to occur. Several criminological studies have reached similar conclusions. For example, in the Cambridge-Somerville Youth Study was found that when adopted by the mother, corporal punishment increased the likelihood of violent behavior and when enforced by the father it increased the likelihood of future serious criminality (Farrington et al., 2003). Additionally, in their study “Unraveling Juvenile Delinquency”, Laub and Sampson (1988) found that both maternal and paternal inconsistent discipline had similar effects on delinquent behaviors.

Finally, the current study revealed that parenting practices have an indirect effect on externalizing behaviors by promoting or reducing school engagement. The mediational analyses indicated that parental involvement and positive parenting might increase the levels of school engagement, which, in turn, appear to contribute for a reduction in externalizing behaviors. In contrast, poor supervision, inconsistent discipline, and corporal punishment might weaken school engagement, which seems to lead to an increase in externalizing behaviors. These data reinforce the notion that school and family factors should not be dissociated from each other when aiming to study their influence on disruptive behaviors. In turn, they should be studied together, thus allowing the understanding of their real impact on an individual’s developmental path (Janssen et al., 2016; Mann et al., 2016). Furthermore, these results emphasize the major aim of this study, which was to verify if the different contexts surrounding the youth and the different relationships they establish with others would have a joint impact in the occurrence of externalizing behaviors. With the achieved results one can conclude that there is a fundamental influence of social bonds in the promotion or demotion of externalizing behaviors and that these bonds are strongly interrelated with each other.

Despite the contributions made by this research, there are a few limitations that should be noted. First of all, this study used a convenience sample, which means it is not possible to generalize the results since the sample is not representative. Future research may overcome this limitation by using a randomly selected sample, using different schools. Furthermore, the possible existence of some biases that might have undermined our data should be acknowledged. Specifically, self-report data, like the one adopted in the current study, holds a risk for social desirability bias. Future research should control for this variable. Employing, for example, an additional method of data collection (e.g., teacher and parents’ reports) could also help overcome this limitation. Also, when the data were collected, the students had just returned to face-to-face teaching after months of confinement, due to Covid-19. The impact the pandemic period had on children and youth and how it affected their perceptions of school it is not known, but one might consider that this might have had an influence on the data obtained. This might be verified by replicating this study in other schools and at different times less influenced by the pandemic. Finally, given the cross-sectional nature of the current research, the results obtained are correlational, and it is not possible to establish casual relations. This is particularly important in the relationship between school engagement and externalizing behaviors, since it is theoretically possible to argue that both the lack of school engagement leads to these behaviors and vice versa (Wang & Fredricks, 2014). On this matter, previous studies suggested that both externalizing behaviors and lack of school engagement would both be consequences of a wider syndrome of behavioral problems, as part of an underlying tendency toward deviance or youthful rebellion (Donovan & Jessor, 1985; Hirschfield & Gasper, 2011). Furthermore, although it is expected that youth who are not engaged at school have a higher propensity to present delinquent behaviros, this does not mean that the lack of engagement is the cause of it (Steinberg & Avenevoli, 1998). In fact, what originated the lack of engagement could be the same thing that contributed to behavioral problems - not only are there risk-prone adolescents, but there are also risk-prone contexts. The results of this study hint in precisely that direction: parenting practices have been shown to influence both school engagement and levels of externalizing behaviors. Longitudinal research is needed to help determine the causal directions of these findings.

Theoretical and practical implications

Regardless of its limitations, the current study has important theoretical and practical implications and represents an added value to the field of research on the phenomenon of youth externalizing behaviors and its correlates.

In fact, the results support ecological (e.g. Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) and developmental perspectives (e.g. Sampson & Laub, 1995; Thornberry, 2005) in explaining the link between family, school and externalizing behaviors, by suggesting that both parenting and schools can act as risk or protective contexts in youth development. As we have tried to highlight throughout this article, the relationships that pre-adolescents and adolescents establish with their parents and with their school can provide them with the necessary support to balance the typical cognitive, social, and emotional changes of this developmental stage. Parents can support their children and encourage them to get involved in academic learning and school activities, while teachers and other school staff can promote a greater attachment to school by creating positive and trusting relationships with students. However, as our results suggest, these relationships are not as clear and linear as they appear to be, but rather a complex network of interactions worthy of research (Thornberry et al., 1991). Therefore, this study sought to bring clues in that direction and to emphasize the need to look at behavioral problems as multidimensional constructs differently influenced by several risk and protective factors, which, in turn, also interact with each other. Future research should explore how other individual and social factors, such as self-control, deviant peers or neighborhood features can affect externalizing behaviors, taking also in account cultural, demographic and gender differences. Regarding this, it should be noted that, to the best of our knowledge, this study constitutes a pioneering research in Portugal, which has corroborated findings from other studies conducted on countries with different cultures and backgrounds, thus highlighting the importance and strength of our findings. Finally, the mechanisms by which school climate and school engagement can affect youth externalizing behaviors should also be explored in future studies. This knowledge is crucial to develop more complex criminological theories, but also to inform professionals and school public policy reforms.

Finally, our outcomes are suggestive of promising areas of action and have important practical implications. They suggest that parents and school agents should work together to promote youth connectedness to school, preventing, even if indirectly, the development of externalizing behaviors. Whether at the universal, indicated or selective level, our findings call for efforts to implementing parenting skills training programs designed to improve positive parenting practices (e.g. consistent and inductive discipline strategies, parental warmth and involvement), and efforts to support schools with interventions aimed at promoting school engagement, safety and discipline. Those are cost-effective multidimensional interventions that may have a far-reaching impact on children and youth development. For example, the Triple P - Positive Parenting Program, a parent-training program, has shown to be effective in improving positive and healthy parent-children relationships, reducing child abuse and children’s emotional and behavioral problems (Nowak & Heinrichs, 2008; Prinz et al., 2009). Regarding school interventions, social and emotional learning programs, designed to improve not only cognitive skills, but also emotion regulation seem to be particularly relevant to increase student’s motivation, participation and bonding to school. For example, the STEP - School Transitional Environment Program, a school-based intervention designed to reduce student anonymity, increase responsibility and respect to school norms, proved to be effective in decreasing school transition stress and conduct problems, promoting academic performance, academic expectations, and positive classroom behaviors (Feiner et al., 1994). Another example is the Child–Parent Center, a school- and family-based early intervention program that aimed to foster school success and social competence, by providing a stable learning environment and parent involvement in children’s education (Reynolds & Suh–Ruu Ou, 2011). The positive impact of these interventions in multiple contexts of youth’s lives emphasizes the need to create public policies specifically focused on creating a protective family and school environment. This is particularly important for countries such as Portugal which, like others, present a school curriculum that is especially focused on academic success, and provides less attention to the development of social and emotional skills that are fundamental to create a safer and more trusting school environment, but also to prevent the development of youth behavior problems.

Conclusion

In summary, this study contributes to a broader insight on the literature concerning risk and protective factors for externalizing behaviors, by addressing the role that the complex interaction between two of the most important socialization contexts for children and youth, namely school and family, play in explaining this phenomenon. Findings suggested that positive parenting strategies, as well, as a positive school climate are crucial factors for enhancing children and youth’s normative development. Moreover, and confirming previous studies, results showed that negative parenting is able to either, directly or indirectly, influence, in a negative fashion, both school engagement and externalizing conducts. Taking together, these results provide important clues for supporting theoretical breakthrough and comprehensive evidence-based prevention strategies, focusing on the promotion of parental involvement and on the creation of a safe, trusting and pro-social school environment for children and youth.

Availability of data and materials

This manuscript’s data will not be deposited.

References

Achenbach, T., & Rescorla, L. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles: Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 6–18, teacher’s Report Form, Youth Self Report: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington: ASEBA.

Achenbach, T., Becker, A., Döpfner, M., Heiervang, E., Roessner, V., Steinhausen, H., & Rothenberger, A. (2008). Multicultural assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology with ASEBA and SDQ instruments: Research findings, applications, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(3), 251–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01867.x

Aldridge, J., McChesney, K., & Afari, E. (2018). Relationships between school climate, bullying and delinquent behaviours. Learning Environments Research, 21, 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-017-9249-6

Apel, R., & Kaukinen, C. (2008). On the relationship between famlily structure and antissocial behavior: parental cohabitation and blended households. Criminology, 46(1), 35–70. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2008.00107.x

Astor, R. A., Guerra, N., & Van Acker, R. (2010). How can we improve school safety research? Educational researcher, 39(1), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.3102/2F0013189X09357619

Bear, G., Gaskin, C., Blank, J., & Chen, F. (2011). Delaware School Climate Survey Student: Its factor structure, concurrent validity, and reliability. Journal of School Psychology, 49, 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2011.01.001

Benard, B. (1991). Fostering resiliency in kids: Protective factors in the family, school and community. National Resilience Resource Center.

Bender, K. (2012). The mediating effect of school engagement in the relationship between youth maltreatment and juvenile delinquency. Children & Schools, 34(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdr001

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. (1998). The ecology of develop-mental processes. In W. Damon, & R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (5,5th Ed.,., pp. 993–1027). New York: Wiley.

Brookmeyer, K., Fanti, K., & Henrich, C. (2006). Schools, parents, and youth violence: A multilevel, ecological analysis. Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology, 35(4), 504–514. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_2

Catalano, R. F., Haggerty, K. P., Oesterie, S., Fleming, C. B., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). The importance of bonding to schools for healthy development: Findings from the social development research group. The Journal of School Health, 74, 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08281.x

Cohen, J., McCabe, E., Michelli, N., & Pickeral, T. (2009). School climate: Research, policy, practice, and teacher education. Teachers College Record, 111, 180–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810911100108

Cole, M., Cole, S., & Lightfoot, C. (2013). The development of children, 7th Edition. New York: Worth Publishers.

Christle, C., Jolivette, K., & Nelson, C. (2005). Breaking the school to prison pipeline: Identifying school risk and protective factors for youth delinquency. Exceptionality, 13(2), 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327035ex1302_2

Dishion, T., Nelson, S., & Bullock, B. (2004). Premature adolescent autonomy: Parent disengagement and deviant peer process in the amplification of problem behaviour. Journal of adolescence, 27(5), 515–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.005

Donovan, J. E., & Jessor, R. (1985). Structure of problem behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 890–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.53.6.890

Elsaesser, C., Gorman-Smith, D., & Henry, D. (2013). The role of the school environment in relational aggression and victimization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(2), 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9839-7

Escribano, S., Aniorte, J., & Orgilés, M. (2013). Factor structure and psychometric properties of the spanish version of the Alabama parenting questionnaire (APQ) for children. Psicothema, 25(3), 324–329. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2012.315

Esposito, C. (1999). Learning in urban blight: School climate and its effect on the school performance of urban, minority low-income children. School Psychology Review, 28, 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.1999.12085971

Farrington, D. (2007). Childhood risk factors and risk-focused prevention. In M. Maguire, R. Morgan & R. Reiner (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of criminology, 4th Edition (pp. 602–640). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Farrington, D., Loeber, R., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (2003). How can the relationship between race and violence be explained? In D. F. Hawkins (Ed.), Violent crime: Assessing race and ethnic differences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511499456.014

Farrington, D., & Welsh, B. (2007). Saving children from a life of crime: Early risk factors and effective interventions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Feiner, R. D., Brand, S., Adan, A. M., Mulhall, P. F., Flowers, N., Sartain, B., & Dubois, D. L. (1994). Restructuring the ecology of the school as an approach to prevention during school transitions: Longitudinal follow-ups and extensions of the School Transitional Environment Project (STEP). Prevention in Human Services, 10(2), 103–136. https://doi.org/10.1300/J293v10n02_07

Fischer, D. (1983). Parental supervision and delinquency. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 56(2), 635–640. https://doi.org/10.2466%2Fpms.1983.56.2.635.

Franco, K., Baumler, E., Torres, E. D., Lu, Y., Wood, L., & Temple, J. R. (2022). The link between school climate and mental health among an ethnically diverse sample of middle school youth. Current psychology, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03016-y

Frick, P., Christian, R., & Wootton, J. (1999). Age trends in the association between parenting practices and conduct problems. Behavior modification, 23(1), 106–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0145445599231005

Furlong, M., Whipple, A., Jean, G., Simental, J., Soliz, A., & Punthuna, S. (2003). Multiple contexts of school engagement: Moving toward a unifying framework for educational research and practice. The California School Psychologist, 8(1), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03340899

Gardner, T., Dishion, T., & Connell, A. (2008). Adolescent self-regulation as resilience: Resistance to antisocial behavior within the deviant peer context. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9176-6

Gault-Sherman, M. (2012). It’s a Two-Way Street: The bidirectional relationship between parenting and delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(2), 121–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9656-4

Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 539–579. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.128.4.539

Gottfredson, D. (2000). Schools and delinquency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gottfredson, G. (2012). Schools and delinquency. In B. Feld, & D. Bishop (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Juvenile Crime and Juvenile Justice (pp. 203–225). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gottfredson, G., Gottfredson, D., Payne, A., & Gottfredson, N. (2005). School climate predictors of school disorder: Results from a national study of delinquency prevention in schools. Journal of research in crime and delinquency, 42(4), 412–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0022427804271931

Graham, R., & Weems, C. (2015). Identifying moderators of the link between parent and child anxiety sensitivity: The roles of gender, positive parenting, and corporal punishment. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 43(5), 885–893. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9945-y

Grusec, J. E., & Davidov, M. (2015). Analyzing socialization from a domain–specific perspective. In J. E. Grusec, & P. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 158–181). New York: The Guilford Press.

Halgunseth, L., Perkins, D., Lippold, M., & Nix, R. (2013). Delinquent-oriented attitudes mediate the relation between parental inconsistent discipline and early adolescent behavior. Journal of family psychology, 27(2), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031962

Hann, D. (2002). Taking stock of risk factors for child/youth externalizing behavior problems. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Mental Health.

Hayes, A. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd Edition) London: The Guilford Press.

Hayes, A., Montoya, A., & Rockwood, N. (2017). The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modelling. Australasian Marketing Journal, 25(1), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.02.001

Hill, N. E., & Wang, M. T. (2015). From middle school to college: Developing aspirations, promoting engagement, and indirect pathways from parenting to post high school enrollment. Developmental psychology, 51(2), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038367

Hirschfield, P., & Gasper, J. (2011). The relationship between school engagement and delinquency in late childhood and early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9579-5

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of Delinquency. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Hoeve, M., Dubas, J., Eichelsheim, V., van der Laan, P. H., Smeenk, W., & Gerris, J. (2009). The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A Meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(6), 749–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8

Hoeve, M., Stams, G., van der Put, C., Dubas, J., van der Laan, P., & Gerris, J. (2012). A meta-analysis of attachment to parents and delinquency. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 771–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9608-1

Ivanova, M., Achenbach, T., Rescorla, L., Dumenci, L., Almqvist, F., Bilenberg, N., et al. (2007). The generalizability of the Youth Self-Report syndrome structure in 23 societies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 729–738. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.729

Janssen, H., Eichelsheim, V., Deković, M., & Bruinsma, G. (2016). How is parenting related to adolescent delinquency? A between-and within-person analysis of the mediating role of self-control, delinquent attitudes, peer delinquency, and time spent in criminogenic settings. European Journal of Criminology, 13(2), 169–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370815608881

Jimerson, S., Campos, E., & Greif, J. (2003). Towards an understanding of definitions and measures of student engagement in schools and related terms. The California School Psychologist, 8, 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03340893

Juang, L. P., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2002). The relationship between adolescent academic capability beliefs, parenting and school grades. Journal of Adolescence, 25, 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2001.0445

Kaplan, A., Gheen, M., & Midgley, C. (2002). Classroom goal structure and student disruptive behaviour. British journal of educational psychology, 72(2), 191–211. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709902158847

Karcher, M. J. (2002a). Connectedness and school violence: A framework for developmental interventions. In E. Gerler (Ed.), Handbook of school violence (7–40). Binghamton, NY: Haworth.

Karcher, M. J. (2002b). The cycle of violence and disconnection among rural middle school students: Teacher disconnectedness as a consequence of violence. Journal of School Violence, 1(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1300/J202v01n01_03

Kasen, S., Cohen, P., & Brook, J. (1998). Adolescent School Experiences and Dropout, adolescent pregnancy, and Young Adult Deviant Behavior. Journal of adolescent research, 13(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0743554898131004

Keil, V., & Price, J. M. (2006). Externalizing behavior disorders in child welfare settings: Definition, prevalence, and implications for assessment and treatment. Children and youth services review, 28(7), 761–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.08.006

Kirby, D. (2001). Understanding what works and what doesn’t in reducing adolescent risk taking. Family Planning Perspectives, 33, 276–281. https://doi.org/10.2307/3030195

LaRusso, M., & Selman, R. (2011). Early adolescent health risk behaviors, conflict resolution strategies, and school climate. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(6), 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2011.05.003

Laub, J., & Sampson, R. (1988). Unraveling families and delinquency: Reanalysis of the gluecks’ data. Criminology, 26(3), 355–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1988.tb00846.x

Leiber, M., Mack, K., & Featherstone, R. (2009). Family structure, family processes, economic factors, and delinquency similarities and differences by race and ethnicity. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 7(2), 79–99. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204008327144

Liu, J. (2004). Childhood externalizing behavior: Theory and implications. Journal of child and adolescent psychiatric nursing, 17(3), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2004.tb00003.x

Liu, R. (2018). Physical discipline and verbal punishment: An assessment of domain and gender-specific effects on delinquency among chinese adolescents. Youth & Society, 50(7), 871–890. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0044118X15618836

Li, Y., & Lerner, R. (2011). Trajectories of school engagement during adolescence: Implications for grades, depression, delinquency, and substance use. Developmental psychology, 47(1), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021307

Loeber, R., Green, S. M., Keenan, K., & Lahey, B. B. (1995). Which boys will fare worse? Early predictors of the onset of conduct disorder in a six-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Psychiatry, 34, 499–509. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199504000-00017

Loeber, R., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (1986). Family factors as correlates and predictors of juvenile conduct problems and delinquency. In M. H. Tonry, & N. Morris (Eds.), Crime and justice: An annual review of research (Vol. 7). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Loeber, R., Wung, P., Keenan, K., Giroux, B., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., Van Kammen, W. B., & Maugham, B. (1993). Developmental pathways in disruptive child behavior. Development and psychopathology, 5(1–2), 103–133. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400004296

Loukas, A., Suzuki, R., & Horton, K. D. (2006). Examining school connectedness as a mediator of school climate effects. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00504.x

Mann, F., Patterson, M., Grotzinger, A., Kretsch, N., Tackett, J., Tucker-Drob, E., & Harden, K. (2016). Sensation seeking, peer deviance, and genetic influences on adolescent delinquency: Evidence for person-environment correlation and interaction. Journal of abnormal psychology, 125(5), 679–691. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000160

Marcone, R., Affuso, G., & Borrone, A. (2020). Parenting styles and children’s internalizing-externalizing behavior: The mediating role of behavioral regulation. Current Psychology, 39(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9757-7

McCord, J. (1997). On discipline. Psychological Inquiry, 8(3), 215–217. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0803_10

McEvoy, A., & Welker, R. (2000). Antisocial behavior, academic failure, and school climate: A critical review. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral disorders, 8(3), 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F106342660000800301

McKee, L., Colletti, C., Rakow, A., Jones, D., & Forehand, R. (2008). Parenting and child externalizing behaviors: Are the associations specific or diffuse? Aggression and violent behavior, 13(3), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.005

Melo, M., & Guerra, C. (2020). Clima de escola e envolvimento de estudantes do 3º ciclo do ensino básico. Revista Psicologia em Pesquisa, 14(1), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.34019/1982-1247.2020.v14.27611

Merrin, G., Davis, J., Berry, D., & Espelage, D. (2019). Developmental changes in deviant and violent behaviors from early to late adolescence: Associations with parental monitoring and peer deviance. Psychology of violence, 9(2), 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000207