Abstract

Objective: In the transition to college, students with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) often face difficulties. Parental support may aid in the successful adjustment to college, and a strong parent-child relationship (PCR) may optimize the balance between autonomy and support necessary during this transition. Method: Few studies have examined this; therefore, a qualitative study using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was conducted. First- and second-year college students with ADHD participated in open-ended, one-on-one interviews (N = 11; 64% women, 91% White). Results: The two broad categories of findings included Parental Support and the Renegotiation of the Parent-Child Relationship. Participants described feeling supported by their parents in the progress toward their short- and long-term goals. Students described this support as helpful when they managed or initiated the contact, but as unhelpful when the parent was perceived as over involved. They described a strong PCR in this transition as helpful to their adjustment and enjoyed the renegotiation of the PCR in terms of their own increased autonomy and responsibility. Many additional themes and sub-themes are described herein. Conclusion: Optimal levels of involvement and support from parents in the context of a strong PCR is beneficial for adjustment to college for those with ADHD. We discuss the clinical implications of our findings, such as therapists helping families transition to college, and working with college students with ADHD on an adaptive renegotiation of the PCR in their transition to adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that is characterized by symptoms of inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity, as well as impairment across multiple settings (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2022). Most individuals with ADHD experience persistent symptoms and impairment that require intervention across the lifespan, especially as they transition between developmental stages. In recent years, individuals with ADHD have enrolled in college at increasing rates (college student ADHD prevalence rates range from 2 to 8%; DuPaul et al., 2009), and this group makes up approximately 25% of those who receive disability support services (DuPaul et al., 2009). Although they enroll at higher rates than in the past, college students with ADHD arrive less prepared for college life than their non-ADHD peers (e.g., lower college readiness in terms of academics, managing daily tasks, staying organized; Canu et al., 2021). Consequently, fewer students with ADHD graduate with a bachelor’s degree, as compared with their non-diagnosed peers (Advokat et al., 2011; Kuriyan et al., 2013). Although cognitive behavioral interventions, medications, and academic accommodations may improve ADHD symptoms and academic performance in college, an achievement gap remains (DuPaul et al., 2009; Stevens, Hartung et al., 2019).

Support and involvement from parents during the early semesters of college may help students adjust to college, given their key role in helping to manage their child’s ADHD during childhood and adolescence (we will use the term parent herein to refer to a consistent primary adult caregiver to a child). As such, abruptly losing parental assistance and support in the transition to college can be detrimental for those with ADHD (Fleming & McMahon, 2012; Meinzer et al., 2015). On the other hand, college students with ADHD who receive continued support from their parents may be better equipped to face the obstacles salient for this population (i.e., planning to study during large amounts of unstructured time, avoiding procrastination, scheduling appointments, providing daily/weekly reminders) in the more demanding environment of higher education (Fleming & McMahon, 2012).

However, college students with ADHD may vary in whether they accept help and advice from their parents based on their parent-child relationship (PCR) quality. For example, students with ADHD who have a positive relationship with their parents, and whose parents maintain optimal boundaries given their adult child’s developmental level, are likely more accepting of advice, and view parent support as helpful (Nelson & Walker, 2013). Conversely, students with ADHD who have a poor relationship with their parents may view suggestions as “nitpicking” or attempts to micromanage their lives (Nelson et al., 2015). In this case, a negative parent-child interaction may occur in which the student becomes emotionally dysregulated and rejects the parental support, and the parent may be less likely to provide further support or may do so in a way that is less-than-optimal (Markel & Wiener, 2014). This pattern of negative exchanges between parents and their college students with ADHD may hinder college adjustment (Padilla-Walker et al., 2021). All told, how college students with ADHD perceive their parents’ involvement (i.e., genuinely supportive vs. attempts to control) will likely impact their transition to college. Thus, the primary aim of the current study was to examine how college students with ADHD view their parents’ support and involvement and their PCR in the beginning semesters of college.

The parent-child relationship (PCR) and ADHD in adolescence

For adolescents with ADHD, their relationship with parents might be conflictual given that parents of children with ADHD demonstrate negative parenting strategies and higher levels parent-child conflict exist. Although some conflict is developmentally normative during adolescence, adolescents with ADHD argue with their parents about more topics (e.g., curfew and allowance) and report higher levels of conflict (Markel & Wiener, 2014) than those without ADHD. Moreover, adolescents with ADHD may view their parents as “nagging” them and trying to control their lives, while the adolescent attempts to exert their independence. Although separating from parents and completing tasks independently are developmentally appropriate, adolescents with ADHD typically require more involvement from parents, particularly to manage academic responsibilities (e.g., homework completion, study time) and life skills (e.g., cleaning, managing a work schedule) which are impaired due to the ADHD (Sibley et al., 2016). Therefore, adolescents with ADHD may gladly accept parental support, resent the support, or feel ambivalent about the support in an unpredictable pattern. These conflicting feelings about their parents’ involvement sets up an opportunity to renegotiate the PCR as the adolescent becomes an emerging adult (18–25 years; Arnett & Schwab, 2012) and begins college. Indeed, a strong PCR and an authoritative parenting style (e.g., balancing high expectations with high levels of warmth) act as buffers against negative outcomes in the transition from adolescence into emerging adulthood, including academic performance, emotional adjustment, and social functioning (Johnson et al., 2010).

Parental support and the PCR for College students with ADHD

College students may rely more heavily on their parents for support in the beginning months or semesters of college, as they leave their social networks from high school and may not yet have strong social connections. In fact, college students with ADHD reported that parental support was the most salient support they received in the first semesters of college in a qualitative study with 15 participants (Meaux et al., 2009). Similarly, in a small cross-sectional study, students with ADHD (n = 17) reported receiving higher levels of parental support than peer support, while their non-diagnosed counterparts (n = 19) reported receiving greater support from their peers (Wilmshurst et al., 2011). Based on this limited evidence, it appears that for college students with ADHD, parents remain an important scaffold in the transition to college, as students begin to form new peer social networks. However, we do not yet understand how college students view their parents’ involvement (i.e., beneficial vs. detrimental), and how the PCR is renegotiated during this major developmental transition.

For college students with ADHD, positive interactions with parents coupled with low levels of conflict in the PCR have been associated with a better quality of life (e.g., physical well-being, personal growth, social functioning; Greenwald-Mayes, 2002). Further, an authoritative parenting style has been linked with better academic adjustment and fewer ADHD, depression, and anxiety symptoms (Jones et al., 2015; Stevens, Canu et al., 2019. Similarly, college students with many ADHD symptoms reported lower levels of depression in the presence of parental warmth, involvement, and autonomy-granting. In fact, the quality of the parenting style mediated the relation between ADHD symptoms and depression (Meinzer et al., 2015). Taken together, results from the small literature on parenting, the PCR, and ADHD in college students suggests that the quality of the PCR and authoritative parenting lead to better outcomes and reduce the likelihood of comorbid mood and anxiety difficulties.

It should also be noted that for typically developing college students (i.e., those without ADHD), there are mixed findings regarding college adjustment in the presence of more involved parenting.Footnote 1 Even in the presence of high levels of emotional support from parents, high parental control is associated with lower levels of academic engagement, poor PCR quality, increased psychopathology, lower social self-efficacy, and less effective use of coping strategies (Padilla-Walker & Nelson, 2012). Conversely, more involved parenting is also linked with increased college engagement, a positive PCR, and more help with solving problems (Padilla-Walker & Nelson, 2012). However, the distinction between high parental control and more involved parenting is not well understood; therefore, it is important to further delineate the differences so that effective recommendations can be made. This is especially important for those with ADHD given their parents may be more involved throughout childhood and adolescence because of the impairments related to the disorder.

Current study

The current study was designed to explore how college students with ADHD perceive involvement from their parents in the early semesters of college. The purpose of this study was to describe and explain the nature of parental involvement and support for first- or second-year college students with ADHD using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA; Smith et al., 2009). One-on-one interviews with college freshmen and sophomores with ADHD were conducted to provide detailed accounts of their experiences related to the support they received from their parents during the first semester of college.

Method

Interpretative phenomenological analysis

IPA is an inductive investigative approach with its roots in phenomenological psychology. Participants’ descriptions of their lived experiences are analyzed for a deeper understanding of the phenomenon. IPA allows researchers to answer queries related to describing a phenomenon embedded in these lived experiences accounting for contextual factors (e.g., ADHD symptom severity) in the environment (i.e., phenomenological approach; Smith et al., 2009). Researchers make meaning of participants’ descriptions of their lived experiences, detecting meanings participants may not have uncovered themselves (Smith et al., 2009). This occurs by carefully analyzing the transcriptions of participant interviews on multiple levels. Ideas and themes emerge from reviewing the transcriptions in their entirety, as well as analyzing at the paragraph, sentence, and phrase levels.

Participants

The participants in this study were 11 college students with ADHD (4 men, 7 women; 2 freshmen, 9 sophomores; Table 1). All were first-time, full-time college students who were in contact with both biological parents (all parents were in heterosexual married relationships at the time of data collection). The students completed the online screener and participated in the interview (Appendix A). The mean age of the 11 participants was 19.36 years (SD = 0.67; range = 18–20 years). Participants were mostly White (n = 10; 1 participant reported a biracial background). Most reported they were diagnosed by a physician (n = 9; 2 students reported being diagnosed by a psychologist), and the mean age of diagnosis was 10.50 years (SD = 4.02; range = 6–17 years). Most participants reported currently taking medication to treat ADHD symptoms (n = 9); all reported living away from their parents, either on campus (n = 6) or off-campus (n = 5).

For all participants, ADHD presentation was reported for childhood (inattentive presentation n = 6, combined presentation n = 5) and currently (inattentive presentation n = 5, combined presentation n = 6) based on the clinical interview results. Participants’ self-reported high school GPAs ranged from 2.30 to 4.00 (M = 3.28, SD = 0.53) and self-reported college GPAs ranged from 2.50 to 3.80 (M = 2.99, SD = 0.41).

The role of the researchers and data collection and analysis

The researchers brought inherent biases to the data collection and analyses based on our backgrounds and experiences with college students with ADHD. The first author, AS, was a doctoral candidate in clinical psychology at the time of the data collection and analysis. She has several years of clinical and research experience working with college students with ADHD. AS completed the interviews, analyzed transcripts, and drew out the first versions of themes and thematic maps. JS was also a doctoral student at the time of data collection and analysis. JS was a middle and high school teacher for several years prior to pursuing her doctorate in clinical psychology and has since accrued substantial clinical experience focusing on college students with ADHD. JS helped revise and finalize themes and the thematic map. CH is a professor and clinical psychologist with over 30 years of experience in clinical and research settings related to ADHD. CH advised AS in the development of the project, during data collection and analysis, and helped finalize themes and the thematic map. EL is a clinical psychologist and professor with 20 years of ADHD-related research and clinical experience. EL advised AS on the design and methodology of the study but was not involved in the data collection or analysis. Finally, two of the four authors have immediate family members with a diagnosis of ADHD.

Participants were recruited from a public four-year university in the Mountain West region of the United States during 2018 and 2019. The university enrolls approximately 12,000 attend this university (80% at the undergraduate level), 52% women, 66% in-state residency, 5% international students. The university reports the following rates of student race/ethnicity: 0.6% American Indian/Alaska Native, 1% Asian, 1% Black or African American, 6% Hispanic, 0.1% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 72% White (source blinded). Potential participants from the Psychology Department research pool were those who identified having a previous ADHD diagnosis and were in their second, third, or fourth semesters at college. These select potential participants were contacted by the researcher (n = 26) via email with a flier advertising the study. After expressing initial interest, students (n = 17) completed a brief online screener survey that included the consent form, demographics/background information (e.g., sex, age, race/ethnicity), ADHD diagnosis information, medication status, DSM-5 ADHD childhood and current symptom rating forms, comorbid psychological disorders (APA, 2013), and the Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale (WFIRS; Weiss, 2000). Based on their answers on the screener, eligible participants were invited to the full interview. Students with comorbid mood, learning, substance abuse, or trauma-related disorders were included in the study because of the high prevalence of these comorbidities with ADHD (Anastopoulos et al., 2018). Five eligible participants elected not to complete the interview, and one other completed the interview, but the data were not usable (i.e., diagnosis of ASD, and had low insight, did not verbalize personal experiences with parents in the transition to college). The interviews were conducted by AS and were audio-recorded (see Appendix A for interview protocol). Audio files were de-identified and transcribed using an encrypted transcription service (Rev Transcription, 2018). Participants were administered a semi-structured diagnostic clinical interview to confirm the validity of their reported ADHD diagnosis (ACDS; Adler & Cohen, 2004). In all, the interviews took 45 to 60 min and were all conducted in 2018 and 2019. Participants were compensated with two research participation credits for a class or $20.

Data were organized using NVivo 12 qualitative research software (QSR International, 2018). Transcripts were analyzed by AS throughout the data collection process to determine when saturation of themes occurred (i.e., a point at which no novel themes are identified; Hennink et al., 2017) and to determine whether the interview protocol needed to be modified. Data analysis was based on methods from Smith et al. (2009) and Saldaña (2016), including familiarization with the data, line-by-line notation and analysis, development of themes, reviewing of themes, and creating thematic maps. Analysis moved back and forth across these steps to yield the most valid results and interpretations possible. Final conceptualizations of the relations across themes were discussed with advanced graduate students with knowledge of ADHD in college students in addition to AS, CH, and JS to improve validity of themes and thematic maps.

Results

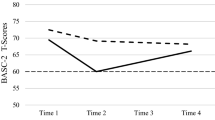

Participant responses were categorized into two broad categories: (1) Parental Support and (2) Renegotiation of the PCR (see Fig. 1 for thematic maps). Within the Parental Support category, emergent themes included (A) Daily/Short-Term Parent Support (sub-themes are presented in order by frequency, beginning with those most frequently discussed: communication frequency, communication content, advice from parents, mom vs. dad, and satisfaction of communication) and (B) Cumulative/Long-Term Parent Support (sub-themes are presented in order by frequency, beginning with the most frequently discussed: emotional support from parents, parent style, and PCR before college).

Within Category 2) Renegotiation of the PCR, two themes emerged: (A) Adaptive Renegotiation of the PCR (subthemes: improvements in the PCR after the transition to college, increased independence, setting boundaries, and parents provide autonomy and support) and (B) Conflictual Renegotiation of the PCR (sub-themes: over involved parenting, tension between parents and independence, under-involved parenting, and disagreements and conflict).

Category 1: parental support

All participants described the ways their parents supported them in the transition to college. They spoke about the daily emotional support and problem solving help they received as well as the impact of the cumulative support they received and quality of the PCR before beginning college.

Theme 1 A: daily/short-term parental support

Participants described the day-to-day support they received from their parents (e.g., how often, who initiated contact, and topics they discussed). Not surprisingly, parents scaffolded their daily support, as parents provided more substantive support in the beginning months of college and decreased communication in subsequent semesters. Example quotes are provided below within each 1 A subtheme.

Communication content

Participants described the content of the communication with their parents as centering on how they were adjusting to college. In their first year, many participants reported informing their parents how their courses were going (e.g., preparing for exams, grades on exams). Participants also described venting to their parents about a difficult exam, but generally not asking for direct advice. However, participants reported asking for help on a specific assignment if their parents had expertise in the subject area. For example, one participant explained, “My mom’s actually a college professor [at a different university] …and she helped me with some of my economics and business classes last semester” (Participant 11). A few participants also discussed asking their parents to help them solve specific problems (e.g., how to obtain extra help for coursework, how to set up a meeting with a professor) and how to access support services for persistent difficulties (e.g., academic accommodations, tutoring). For example, one participant indicated that, “If I tell them I don’t have an idea, they’ll be like, ‘why don’t you ask your friends or talk to your teacher?’ or [provide] other suggestions” (Participant 1). Participants also acknowledged that their parents would encourage regular ADHD medication adherence (e.g., “‘Did you take your medicine?’” Participant 7). Other areas of communication content that participants discussed included maintaining a budget, problems with roommates, selecting or changing majors, applying for jobs, and navigating relationships with peers and romantic partners.

Communication frequency

Participants described communicating with their parents frequently using text messaging, phone calls, social media, and emails. Almost all participants reported they were in contact with at least one parent every day or every-other day through text messaging and/or phone calls. Participant 1 described her frequency of contact: “I pretty much talk to my parents every day. It’s not always through the phone but just through texting…when we talked on the phone it’s 2–3 times a week and it’s a 20-minute conversation.” During the first year of college, the frequency of communication was higher in an effort to allay parents’ fears about their student’s adjustment to and functioning in college. Participants described their parents checking in via text message frequently during their first year (e.g., “They would text me all the time… How are your exams going? …Are you eating enough?” Participant 5). This parent-initiated communication was viewed as more than preferred by the student. However, participants initiated contact with their parents more frequently during periods of increased stress. For example, one participant said “When I was a freshman, I texted my mom almost every day. Just about everything that was stressing me out or things I was struggling with.” (Participant 10). When the communication was initiated by the college student, they reported feeling satisfied with the frequency. While discussing changes in the frequency of communication from the first to second year, one participant explained that his parents initiated many of the check-ins about his classes in the first year, but that he would initiate these conversations during his second year:

Last year, it’d be me mostly asking about home, about how things are going…We’d talk about classes and everything at [university name] because I was a freshman. This year, it’s more…I let them know about my class load and tell them what I’ve got to do. I usually keep it short so I can get back to what I’m doing. I think it’s more of just an update now [second year] compared to last year. (Participant 7)

This statement and others suggest that when college students initiate and control the frequency of communication with their parents, they are more satisfied, and view the level of communication as helpful.

Advice from parents

Parents reportedly provided advice related to adjusting to the first semester in college, as they encouraged their students to become involved in social activities to make friends. Participant 4 reported that her mother encouraged her to join a student organization on campus. She recalled that her mother advised, “You can’t come home yet. You have to make sure you’re adjusted. You have to deal with it. You have to grow with it.” Participant 4 went on to say that she struggled to implement her mother’s advice, as she felt anxious meeting new people and starting a new life in college. Similarly, many participants explained they would often initially disagree with their parents’ recommendation and become upset (e.g., immediately rebuke their parents, abruptly ending a conversation; Participant 5). Participants then described how once they were able to regulate their emotions, they were able to take their parents’ perspective and implement their advice. Participant 5 was able to have a calm conversation with his mother about finances after an initial disagreement. He stated,

If I have a problem, like I didn’t work enough one week and I’m really scared about money, then I’ll shoot my mom a text and be like, ‘Money goes so quick, doesn’t it?’ and she’ll be like, ‘I know, right?’ and then we’ll talk for a bit about it.

Participant 4 also came around to her mother’s advice and explained, “I don’t listen very well, so I was really upset for a while. But then, it’s like every time my mom tells me something and I don’t agree with it, I’m like, ‘Oh, that’s why she said it’.” Other participants described using their parents to “vent” and verbalize their problem-solving process, as they would discuss various options with their parents, and then independently decide on a solution. “It’s nice to talk it out. I wouldn’t say she gives me very good advice” (Participant 8). Overall, participants reported being satisfied knowing they had the autonomy to make decisions independent from their parents, but still be able to seek advice from them.

Mother vs. Father

When describing their daily communication with their parents, several differences emerged related to mothers vs. fathers. Participants reported communicating with their mothers via text message and phone calls more frequently than with their fathers (e.g., “If I have a problem, I’ll go to my mom first,” Participant 5). One participant reported that when he calls home, “Dad’s not as talkative and he’s asking me if [my] grades are good…he’s like, ‘let me know if you need anything. Here’s your mom again’” (Participant 7). Participants explained they talk with their mothers more often because they appreciate the validation of their emotional experiences, how they show empathy, and will listen to them without offering advice immediately. Participants described receiving more emotional support from their mothers and having closer emotional relationships with their mothers.

Satisfaction with communication

Most participants explicitly stated they were pleased with the quality and quantity of communication with their parents. Most participants explained their parents were an integral “support system” and voiced being grateful for the emotional support and advice from their parents (Participant 8). One participant shared the following his parents’ level of communication:

I think it’s really good. I wouldn’t ask for anything different. I think even though it can seem like it’s a bit much, I think if they weren’t as supportive and involved, I would probably be like, I wish there was a little bit more of that (Participant 6).

Thus, overall, Theme 1 A showed that college students with ADHD communicated with their parents almost daily in their first semesters of college, communicated most often with their mothers for emotional support, were hesitant to agree with direct advice at times, and were largely satisfied with the frequency and content of the communication.

Theme 1B: cumulative/long-term parental support

Participants who felt supported in the PCR prior to college reported more satisfaction in the daily/short-term. As such, participants described higher quality PCRs while growing up while also describing appreciation of their daily/short-term support in adjusting to college. Below, participants explained how emotional support from parents and positive PCRs buoyed them when trying to meet the increased demands of college.

Emotional support from parents

Participants discussed how their parents provided them with encouragement because their parents understood the increased academic demands of college, and the fact that ADHD symptoms made it more difficult to adjust and succeed. Participants reported their parents were proud of them for gaining entrance to college and that they provided encouragement when faced with a setback. One participant explained:

Recently we were talking about how I was super stressed. I felt like I was falling apart. I couldn’t keep going and do college…I started freaking out, and my parents were like, ‘Sam [pseudonym], just calm down. You’re okay. You don’t need to get down on yourself because you’ve made it this far. You should be proud of yourself for the good things you’ve done.’ I was like, you’re completely right. I don’t know why I’m freaking out about this. I need to just calm down, just put my mind to it, just focus and get my [expletive] in gear (Participant 11).

Participants explained that their parents’ unconditional support, which began in childhood, had persisted while in college. “It’s really cool to be able to just turn to them and call them whenever I need them and have their support” (Participant 11). Participant 9 referenced their parents’ emotional support and confidence in their decision-making and stated, “Just go for it. You know what you need to do.” Other example statements included, “It’s good to have my mom as a support system” (Participant 4), “They’re super supportive” (Participant 6), “I was very lucky to have parents who cared and wanted to help,” and “They were always there to support me no matter what” (Participant 7).

In all, 9 out of 11 participants discussed being appreciative of the long-term emotional support their parents provided and that this emotional support continued while they adjusted to college. Participants described their parents as providing an emotional safety net that provided them more confidence in overcoming obstacles.

Parent-child relationship before college

Participants also discussed the nature of the PCR before college. For example, completing schoolwork was often a source of conflict before attending college. One participant explained how he would respond to his parent:

I don’t want to do this. Leave me alone. I would go to my room and slam my door. I would sit there and do nothing for a couple of hours. Then I would calm down, apologize, and then end up doing [the homework] (Participant 11).

A few participants stated their relationship with their parents improved after they were diagnosed with ADHD. Similarly, other participants explained they felt more understood by their parents because a parent and/or another family member had been diagnosed with ADHD or displayed ADHD symptoms as well. Participant 1 reported, “I had a good relationship with them before, but now that we are all diagnosed with [ADHD], it’s made us closer because it’s like, ‘I understand what you’re talking about [because] I do the same thing’.” In contrast, one participant reported that her relationship with her parents suffered while growing up because they did not understand an ADHD diagnosis and other mental health disorders (e.g., parents were quick to anger in response to her impulsivity). This participant (#3) stated, “I love my parents dearly, but growing up they were not exactly supportive of any of that stuff [ADHD and mental health] because they just didn’t get it, and it’s not how they were raised.” Thus, some participants reported a strong PCR before college and parents who understood them vis a vis their ADHD diagnosis, whereas other students felt frustrated with their parents during adolescence and did not feel supported regarding their diagnosis.

Category 2: renegotiation of the parent-child relationship

Participants discussed how their relationships changed with their parents as they ventured from adolescence into emerging adulthood. They explained the aspects that led to more of an adaptive renegotiation of the PCR as well as roadblocks they faced that led to more instances of a conflictual renegotiation of the PCR. Many participants reported on both adaptive and conflictual aspects of their renegotiation, as the process was not straightforward or linear.

Theme 2 A. adaptive renegotiation of the parent-child relationship

All participants described positive aspects of their PCRs after beginning college. Participants felt they had attained the goal of gaining college entry and thus gained independence, while still receiving support when needed.

Improvements in the PCR after the transition to college

Participants attributed this improvement to increased independence, not being monitored as closely by their parents (i.e., more egalitarian relationship), having some academic success in college despite ADHD-related challenges, their own increased maturity, and continued parental support and involvement in their lives. One participant noted how being perceived as an adult by his parents led to increased positive interactions:

As I matured, we’ve started to respect each other a little more. I’ve been able to control myself a lot better, and actually talk about it and be an adult about certain situations. Not just be a kid about it and start yelling and get upset. I can actually talk about things reasonably (Participant 11).

Participants expressed pride in receiving positive feedback from their parents about their increased maturity and independence, which in turn, seemed to increase the mutual respect in the dyad. For instance, Participant 2 stated, “They look at me like I’m older now.” Many participants reported getting in fewer arguments with their parents once they moved to college. While discussing changes in interactions with his father, Participant 6 reported, “I think [moving away to college] made [the relationship] better because…if we’re separated, we’re more concerned with how each other are doing.” Another participant indicated that she experienced an improvement in her relationship with her mother because her mother did not monitor her academic activities as closely: “If I go home from [high] school, and she was immediately asking me things, and I was tired. I would get really angry and annoyed.” She went on to say that she enjoys the freedom not to be as closely monitored by her mother and understands that when her mother asks her similar questions of her now, her mother is showing interest in her day.

Increased independence

One example of increased independence included being able to solve problems without input from parents, which led to decreased “nagging” from parents. Participant 7 reported, “I’ve felt a greater sense of independence in my life…I’m living on my own now, working, and [my parents] are there if I need them, but I don’t need to rely on them.” Participants reflected on increased freedom to structure their daily lives, while also noting the difficulty in managing time to complete academic tasks and maintaining motivation to complete household chores. Participant 7 stated, “I put more responsibility on myself…back in high school I had my parents to keep me on track but now I have myself, so I have to reel myself back in if I feel myself getting too off track…I have to control myself and gauge my behavior.” Participants also noted the importance of building a social network to provide support outside of the PCR, which made them feel less dependent on their parents for emotional support. Participant 10 explained, “I’ve learned I need to branch out more. I’ve definitely come a long way … I think just being social and making friends with all the people on your floor in the dorms.” Participant 5 stated, “I’d also say get plugged into something extra-curricular, because if you’re involving yourself too much into your studies, then it’s going to be unhealthy.” Several participants described being fairly independent during the last years of high school and that increased independence prior to leaving home for college allowed them to be even more self-sufficient during the beginning of college. Participant 6 explained, “…Even before, in high school, our family really raised us to be pretty independent, and we’ve always had to work for anything we want that’s not just basic needs.” In all, this subtheme suggests that participants felt supported by their parents in building more independence, especially for those participants whose parents had encouraged independence during high school.

Setting boundaries with parents

Several participants described having to set boundaries with their parents to decrease their parents’ involvement. One participant noted that she had a brief conversation with her mother before college began about her mom taking cues from her: “She wanted to be as involved as I wanted her to be” (Participant 9). Participant 9 felt that this was a helpful and supportive parental strategy. Others reported unspoken boundaries and expectations about the frequency of contact with their parents (e.g., weekly phone call). For example, Participant 4 said,

So, she doesn’t pester me to talk to her, which is really nice. Because I know a lot of parents, when they first get to college, they’re like, ‘call me.’ ‘How is your day? Are you okay? Are you alive?’ My mom just wants me to be like, ‘hey, I’m okay, not dead.’

Thus, participants seemed to be satisfied when new and appropriate boundaries were put in place at the transition to college.

Parents balance autonomy and support

Participants explained their parents encouraged them to figure out how to complete academic tasks independently and were willing to listen and help them find resources on campus, if needed. One participant stated:

So, I think you need to ask your kid what their schedule is like, if they are involved in clubs… ‘I think you had a sociology test today, right? How’d that go?’ Just to check in and make sure they’re okay. If you’re involved, but in a relaxed way, your kid is going to want to talk to you more… Check in, but realize they are 18 and trying to figure it all out. And the first time they’re like, ‘oh I messed up,’ instead of yelling at them, tell them that it’s part of life, here’s how you can fix it (Participant 3).

As exemplified by this quote, participants appreciated involvement from parents that included asking questions, while allowing them to make decisions on their own.

In sum, Theme 2 A illustrated that many participants and their parents interacted in ways that supported adaptive renegotiation of the PCR. Participants felt more independence and received fewer reminders (e.g., “nagging”) from parents once they moved out of the home and they had fewer in-person interactions. Finally, participants welcomed a balanced approach from their parents, where they received support and were encouraged to gain autonomy.

Theme 2B. conflictual renegotiation of the parent-child relationship

Just over half of participants explained difficulties with their PCRs. Participants’ perceptions of too much involvement and/or not enough involvement from parents led participants to experience a conflictual renegotiation of the PCR. For some, these difficulties were a continuation of a poor PCR while growing up and for others, this seemed related to participants beginning college and wanting more independence from their parents.

Higher levels of parental involvement

While some participants characterized instances of parental over involvement as infrequent and understood their parents would be more involved because of their ADHD-related difficulties, many participants were not satisfied with this over involvement. For example, one participant stated, “I think my mom and dad can be a little helicopter-y, but they usually back off if I’m like: I understand, go away now” (Participant 10). Similarly, participants perceived their parents as intruding when parents selected courses for them and made frequent inquiries about friendships and romantic relationships. For example, Participant 3 stated:

Coddling is the worst thing you can do… ‘Did you do good on this test? Did you get to your classes? Did you eat?’ My mom did that for the first two weeks of my first year, but it never seemed like it was in my best interest… And I feel like that puts even more pressure on you because you’re trying to figure it out (Participant 3).

In addition, another participant said: “My mom kind of gets a little bit repetitive when I don’t listen the first time. Just regarding studying. Like, ‘You need to study more. You need to do this.’ I’m like, I’m trying but I don’t have a whole lot of time” (Participant 10). Another participant discussed the negative consequences associated with higher parental involvement. He stated,

I think that parents with kids who have ADHD or dyslexia or something, need to step off a little bit. They can’t be helicopter parents, otherwise they might become narcissistic kids. They’re not going to know how to do anything for themselves, and if they give them too much of that, we’re going to make all these decisions for you, they’re going to become, ‘the world revolves around me’” (Participant 5)

Overall, participants felt their parents were “nagging” them or were over involved when they inserted their opinions when they had not asked for advice, repeatedly asked about the same topic, and when parents completed tasks for participants.

Tension between help from parents and independence

In some instances, participants made conflicting statements about their parents within the same sentence or paragraph. One participant stated:

I feel like my mom raised us to be super independent, but then she’s still holding onto us so much. Which is confusing because she encourages us to be our own person and then she’s like, I want to be in on all of the details (Participant 6).

Other participants stated that the unsolicited advice they received from their parents was information they already knew. As such, they felt that those behaviors were “nagging” from parents (Participant 1). Participants also explained that they felt that their continued reliance on their parents led to feelings of disappointment; they felt they should be able to complete certain tasks without as much oversight from their parents.

Lower levels of parental involvement

A few participants reported experiencing instances in which they desired more involvement and support from their parents. One participant explained that her parents had displayed a pattern of lower involvement while she was growing up, and this low level of involvement continued when she began college. Another participant reported that his parents’ level of involvement decreased abruptly since moving away to begin college, as he stated, “They used to care, and then I got older, and like, ‘you’re old enough to figure stuff out’” (Participant 2). Thus, under-involvement from parents was viewed as unhelpful and the students felt they would benefit from some additional parental support.

Disagreements and conflict

Most participants described minor conflicts that were resolved amicably, while others discussed more longstanding disagreements or conflicts that had not been resolved. For example, Participant 6 stated, “We definitely don’t see eye to eye on everything and it’s hard because it’s complicated to try to explain my experience in school to them.” Another example of frustration with a participant’s mom included, “You are five hours away and consistently yelling at me over something” (Participant 3). This participant went on to compare the parental support her friends received with the lack of support she receives:

Frustrating, really frustrating. Because all of my friends have moms that will call them like, “I miss you so much” or “Come home” or “I made you cookies” or they’ll send them packages. My roommate last year ... her dad was always sending her books ‘cause she reads like a fiend, and stuffed animals, and blankets, and cookies, and he’d make her favorite foods from home. And then my mom would call to yell at me for two hours because I wasn’t at home to do something, and she doesn’t have enough time to do it (Participant 3).

One participant expressed feeling her academic challenges due to ADHD had caused conflict with her parents. She (Participant 8) explained how she desired more understanding from her mother, which can cause disagreements: “I mean, I wish it was easier for her to sympathize and empathize with my issues, but that’s just because she doesn’t have that same life experience.” Finally, another participant reported that she and her mom have minor arguments and that their “disagreements are pretty controlled…They [my parents] taught me to be really patient. And even though it’s hard and you can feel anger is welling up inside of you, to try not to explode and just talk about [it].” In sum, participants described disappointment in some of their parents’ actions or inactions, which led to arguments and a more conflictual PCR.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to explore the nature of parental support in the transition to college from the perspective of college students with ADHD. Two categories emerged from the student interviews: Parental Support and Renegotiation of the PCR; we will discuss each in turn, and will then explore clinical implications, limitations, and future directions.

Parental support

Participants in the current study described daily or almost daily communication with at least one parent (most often mothers) during the initial transition to college, with a reduction in contact over time. Parent support during this time often included advice on everyday tasks such as planning time to do homework and medication compliance, and transitional tips such as encouragement to get involved in college life (e.g., to join student groups). The college students with ADHD in our study largely viewed this support as helpful. Indeed, research has suggested that college students with ADHD benefit from frequent communication with their parents to help them structure their daily lives due to their disorder-related executive functioning deficits (e.g., being forgetful, regulating emotions, impaired motivation; Barkley, 2015). College students are tasked with completing daily responsibilities independently from their parents after moving away to college. Yet, college students with ADHD have less well-developed time management and organizational skills, which impair their ability to complete these tasks, especially in the less structured college environment (Canu et al., 2021; Fleming & McMahon, 2012). The frequent communication with parents seems to have improved our participants’ daily structure, serving as reminders to “stay on track.” It is interesting that most of the parental support was actually maternal support. That is, mothers were much more frequently named as the go-to parent for college students with ADHD in the transition to college. This aligns with research that women in heterosexual couples often bear the burden of a family’s cognitive and emotional labor (Dean et al., 2022), and take on an outsized role in caring for children with mental, behavioral, or physical needs (Goldscheider et al., 2015). Our findings suggest that mothers continue to provide this emotional labor into their child’s emerging adulthood.

As a contrast to mostly reporting satisfaction with the parental support they received, our participants also reported that at times this support was unwanted. They indicated that when they initiated contact with their parents and asked for advice, the support was appreciated. However, when parents were perceived to worry too much and overstep the student’s newfound independence by frequently initiating contact, our participants became annoyed and frustrated. Our participants also admitted that when they initially experienced annoyance or frustration with parental advice, they often ultimately adopted the advice and found it to be helpful.

Given that the transition to college for those with ADHD may exacerbate or contribute to the development of symptoms of depression and anxiety (Anastopoulos et al., 2018), receiving support from parents may buffer against these comorbid problems. Past research has shown that emotional support and validation from parents may be especially relevant for college students with ADHD because they experience academic hardship more frequently than their peers and may be more sensitive to failures (Corbisiero et al., 2013). Likewise, college students with ADHD have a lower self-concept than their peers and feel discouraged and incompetent across life domains (Canu et al., 2021; Greenwald-Mayes, 2002). In all, there are many perceived and actual benefits of parental support in the college transition for students with ADHD.

In contrast to most of the sample, two participants expressed receiving minimal support from their parents in the transition to college. One reported an abrupt loss of support once moving away to college and the other participant reported the minimal support as a pattern that had persisted from adolescence (and reported successfully adjusting to college). Given that college students with ADHD generally have poorer coping skills, lower self-reliance, and have more difficulty establishing new social support networks (Canu et al., 2021; Sacchetti & Lefler, 2017), a lack of parental support may be especially detrimental during the transition to college.

Moreover, our participants indicated that the cumulative effect of parental support from adolescence into the college transition was beneficial. In fact, our participants reported that when the PCR was strong in adolescence, it continued to be strong into college. Additionally, many of our participants reported an improved PCR following their diagnosis of ADHD. Once parents were better able to understand their child’s cluster of symptoms and impairments, they were more compassionate which was welcomed by our participants. These reports are consistent with longitudinal findings with adolescents who were followed into young adulthood. Specifically, parental support and involvement during adolescence (but not necessarily during emerging adulthood) was associated with college enrollment and lower levels of impairment during emerging adulthood (Howard et al., 2016). Thus, it appears that during adolescence, empathy for ADHD-related difficulties and encouraging the completion of college applications was most helpful. In all, an emotional safety net from parents in adolescence may set the stage for emerging adults to feel more confident to take on tasks independently at the beginning of college, with parents–often mothers–providing decreasing levels of support after the initial transition.

Renegotiation of the PCR

The transition into emerging adulthood and college involves a changing dynamic between parents and children in which the relationship begins to shift from being asymmetrical to more symmetrical (e.g., process in which parent and child progress toward seeing each other as equals; Lamb & Lewis, 2011). Our data suggests that this is true for college students with ADHD as well. In fact, our participants reported that they enjoyed their new relationship with their parents when they had independence, when their parents treated them like adults, and when parents voiced pride in their maturity and success. Similarly, Sibley and Yeguez (2018) found that the PCR improved when parents allowed their emerging adults to make decisions independently, while being able to provide advice when necessary. Our participants also reported taking on increasing responsibility (some started this at the end of high school), which amplified their feelings of autonomy, and appreciated that their parents gave them space to make their own choices. Participants also discussed the importance of setting boundaries with their parents in the context of an adaptive renegotiation of the PCR. Participants noted their preference for initiating contact with parents and having the freedom to not respond to their parents immediately.

Beginning college students with ADHD wanted their parents available if needed, but also hoped to engage in more self-reliant behaviors to act as independently as their typical peers. Indeed, setting boundaries with parents allows students with ADHD the autonomy to show their parents they can complete certain tasks without reminders, increasing their self-efficacy. Several participants also reported their parents set boundaries on the amount of assistance they were willing to provide, and other participants reported that their parents encouraged them not to visit home in the first few weeks of college to encourage the formation of new social networks at college. Participants similarly indicated that they shifted their requests for support to their peers more and more. This change to increasingly relying on peer support is in line with typical social development during adolescence and emerging adulthood and is consistent with another qualitative report in which students with ADHD described receiving support from both peers and parents that helped facilitate their adjustment to college (Meaux et al., 2009).

While the college setting is one of the first opportunities for those with ADHD to act as independent adults–which they welcome–it simultaneously is overwhelming for the student. Therefore, it is not surprising that our participants expressed conflicting feelings about their parents’ involvement, as they struggled to determine how much and what kind of parental involvement they preferred. This led to feelings of tension between the college student and parent, as the college student sometimes perceived the parental involvement as intrusive. This suggests that parents of college students with ADHD have a fine line to walk. On one hand the college students appreciated the support and guidance, but on the other hand higher levels of involvement (e.g., providing unsolicited advice) led college students to distance themselves from their parents and experience frustration. This is consistent with past research suggesting that higher levels of parental control and lower autonomy-granting for typically developing college students, even when coupled with emotional support from parents, has been linked with poorer PCR quality (Padilla-Walker & Nelson, 2012). Importantly, the students’ perception of the motivation behind higher parental involvement may impact emerging adult adjustment (Padilla-Walker et al., 2021). College students with ADHD may fare better when more involved parenting is perceived as caring and supportive instead of perceiving the involvement as attempts to maintain control over them. This can be a hard balance for a parent to achieve.

Finally, many of our participants reflected changes in their own behavior significantly contributed to an improved PCR. Students’ more well-developed emotional regulation when receiving feedback from parents appeared to lead to more positive interactions with parents. During adolescence parental “checking in” behavior was viewed as intrusive; however, during the beginning of college, these same parental behaviors were often seen as supportive and helpful. Improved student self-regulation may be due to the maturing brain systems resulting in response inhibition that occurs during emerging adulthood (i.e., prefrontal cortex; default network, mesolimbic system; Nigg, 2005). In all, when independence and autonomy are coupled with support from the parent, and the adult child is better able to regulate their emotions, the quality of the PCR seems to improve for college students with ADHD.

Clinical implications

Parents of young children with ADHD, especially mothers, are often tasked with the management of their child’s disorder (e.g., psychiatric visits, behavioral parent training, managing academic accommodations and school-based interventions, and medication compliance). As children with ADHD become adolescents and emerging adults with ADHD, it is likely difficult for parents to know how to gradually transition this responsibility to their child, and parents might not trust their child to be able to manage these tasks successfully. Thus, it is no wonder that our participants simultaneously reported parental support as helpful and intrusive. Mental health professionals working with these families should be aware of this need for a transition of ADHD-related responsibilities and should work with the families to achieve a gradual transition throughout adolescence and into college. In fact, building a strong PCR prior to transitioning to college may be a protective factor for college students with ADHD, especially because a conflictual PCR may contribute to poor college adjustment (DuPaul et al., 2009). Interventions that include effective parent-adolescent communication skills for those with ADHD can reduce family conflict, which may improve the PCR (Sibley et al., 2013).

When preparing for the transition to college, it is helpful for students with ADHD and their parents to discuss expectations for the nature of communication, as discrepancies in expectations may lead to greater difficulty in renegotiating the PCR (Kenyon & Koerner, 2009). Summer transition or “bridge” programs for incoming freshmen at-risk for poor academic performance typically focus on improving academic skills and do not include parents (Grace-Odeleye & Santiago, 2019). However, it may be helpful for students with ADHD to focus on non-academic aspects of the transition as well (i.e., Maitland & Quinn’s (2011) Ready for Take-Off, a college readiness self-help book for adolescents and their parents), including how they would prefer their parents be involved in the transition and beginning semesters.

Mental health professionals and other college personnel such as student disability support staff who work with college students with ADHD may enhance success by including parents in therapy or in discussions of academic accommodations, if preferred and given permission by the college student. Depending on the nature of treatment goals, having occasional joint sessions with the parent and college student in the context of individual therapy may aid parents in understanding ADHD, how best to support their college student (e.g., waiting for their child to initiate conversations), and can help the college student communicate their involvement preferences with their parent(s). Given that those with ADHD may be functioning a couple of years behind their same-age peers (e.g., emotional regulation) due to delayed neurological maturation (Nigg, 2005), including parents in treatment may be especially appropriate and beneficial to successful adjustment. Joint sessions may also give parents a chance to explain their motivations which may be helpful and give tips about strategies that have worked in the past (e.g., timing of homework, usefulness of extending test-taking time, reinforcement tools). Several treatments for college students with ADHD have emerged in recent years that include components such as interpersonal effectiveness and mindfulness, which target boundary setting with parents and emotional regulation, respectively (Meinzer et al., 2021; Zylowska & Mitchell, 2021). Building these skills may be especially important for college students with ADHD, as our participants described being able to manage emotional dysregulation during conversations with their parents and adjusting parental boundaries as contributing to a positive PCR.

Limitations and future directions

Limitations of the current study should be noted when interpreting the results. An important note on the timing and impact of the data collection: as mentioned in the Method section, all interviews were conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, many college students returned home to live with their parents and attended classes virtually, which had significant negative impacts on students’ level of engagement with their campuses, social isolation, and overall mental health, especially for students with ADHD (Hall & Zygmunt, 2021; Sibley et al., 2021). Thus, the level and nature of parental support and the PCR may look different (e.g., poorer relationships with parents after moving back home during the pandemic) before, during, and after the pandemic. From this perspective, the current results may not generalize as well to the current population of college students with ADHD following the pandemic. For instance, the impact on the PCR during the pandemic while current college students were in high school may have continuing impacts on the level of support provided in the transition to college. Thus, continuing to examine the nature and level of parental involvement and the parent-child relationship in this post-pandemic “new normal” will add to the current findings.

Next, almost all participants described a positive relationship with their parents, and thus students who have poorer relationships with their parents may not have volunteered to participate (i.e., a self-selection bias). The data collected in the current study may not provide perspective for beginning college students with more strained relationships with their parents. It may also be that adolescents with ADHD who experience less involved or overly punitive caregiving are less likely to enter college, and therefore are not represented herein. Relatedly, college student participants with ADHD who had particularly high levels of impairment were likely not able to take the time to schedule and follow-through with this study. Thus, another self-selection bias might have occurred in that only the highest functioning college students with ADHD were able to schedule and keep an appointment with our research team.

Additionally, the sample lacked racial, ethnic, gender identity, and sexual orientation diversity which may have restricted the scope of the findings. Cultural and ethnic differences have been found in the level of closeness with parents as individuals enter emerging adulthood, which may impact adjustment in college (e.g., higher levels of parental involvement among African American and Latinx populations; Arnett & Schwab, 2012), so our sample of primarily White participants cannot capture this diversity. Similarly, all parents discussed in this study were heterosexual couples who were all still married and were the biological parents of the participants. This certainly fails to capture the diversity of American families. Moreover, only four of our participants were men, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to college men with ADHD.

To address these limitations, additional research is needed. Specifically, studies examining the nature of parental involvement in emerging adults with ADHD who do not attend college, or who drop out of college, would help identify how the PCR may be renegotiated for those with possibly more severe ADHD symptoms and impairment. Longitudinal studies that follow high school students with ADHD are needed to better understand links across parental support, the PCR, how adjustment is impacted for those on various educational trajectories, and to identify potential mediators. Quantitative studies examining latent profiles of parenting domains (e.g., support, psychological control, levels of involvement) and whether these profiles are differentially associated with outcomes (e.g., academic performance, depression, risk behaviors) are needed to inform interventions. Studies should include individuals of varied cultural/ethnic backgrounds and gender/sexual orientations to examine the impact of ADHD on diverse families. Future research also should examine various dyads (e.g., mother-daughter, father-son), and larger quantitative samples may provide an opportunity to study sex/gender differences in the context of ADHD and the transition to emerging adulthood. Finally, while the college student perspective is important, future studies should explore parent perspectives on the transition to college.

Conclusion

This study is among the first to qualitatively examine parental support and the renegotiation of the PCR in the transition to college for those with ADHD. Students described frequent communication with their parents, a decrease in conflict following the transition, an appreciation of support from parents, tension between wanting parents’ help and becoming more independent, and some conflict with parents. Students preferred when parents granted autonomy to develop increased independence and provided encouragement during times of increased stress. Parental involvement that is consistent with student expectations will augment evidence-based supports for college students with ADHD, increasing the likelihood of persistence toward the degree.

Data Availability

Data for this qualitative study include interview transcripts and are not publicly available because of participant identifying information included in the transcripts. Upon request, the corresponding author can provide blinded interview transcript excerpts that are not already included in the manuscript results section.

Notes

The levels of parental involvement have been ill-defined. Terms such as over involvement, overparenting, and helicopter parenting have been used to describe what researchers believe is “too much” involvement by parents. Padilla-Walker and Nelson (2012, p.1178) have described it as demonstrating “excessive control” over the emerging adult and “inappropriate amount of involvement” in the emerging adult’s life (p.1178–1179). The terms “higher” and “lower” levels of parental involvement will be used because there is a lack of agreement and understanding of what level of involvement is optimal for college students and because the terms over involvement, overparenting, and helicopter parenting are pejorative and assume that there is an optimal or correct level of involvement.

References

Adler, L., & Cohen, J. (2004). Diagnosis and evaluation of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 27, 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2003.12.003

Advokat, C., Lane, S. M., & Luo, C. (2011). College students with and without ADHD: Comparison of self-report of medication usage, study habits, and academic achievement. Journal of Attention Disorders, 15, 656–666. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054710371168

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition: DSM-5. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: Fifth edition, text revision: DSM-5-TR. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association.

Anastopoulos, A. D., DuPaul, G. J., Weyandt, L. L., Morrissey-Kane, E., Sommer, J. L., & Gudmundsottir, G. G. (2018). Rates and patterns of comorbidity among first-year college students with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47, 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1105137

Arnett, J. J., & Schwab, J. (2012). The Clark University poll of emerging adults: Thriving, struggling, and hopeful. Worcester, MA: Clark University.

Barkley, R. A. (2015). Educational, occupational, dating and marital, and financial impairments in adults with ADHD. In R. A. Barkley (Ed.), Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (pp. 314–342). The Guilford Press.

Canu, W.H., Stevens, A.E., Ranson, L., Hartung, C.M., LaCount, P.A., Lefler, E.K. & Willcutt, E. G. (2021). College readiness: Differences in first-year undergraduates with and without ADHD. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 54(6), 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219420972693

Corbisiero, S., Stieglitz, R. D., Retz, W., & Rösler, M. (2013). Is emotional dysregulation part of the psychopathology of ADHD in adults? ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 5(2), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-012-0097-z

Dean, L., Churchill, B., & Ruppanner, L. (2022). The mental load: Building a deeper theoretical understanding of how cognitive and emotional labor overload women and mothers. Community Work & Family, 25(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2021.2002813

DuPaul, G. J., Weyandt, L. L., O’Dell, S. M., & Varejao, M. (2009). College students with ADHD: Current status and future directions. Journal of Attention Disorders, 13, 234–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054709340650

Fleming, A. P., & McMahon, R. J. (2012). Developmental context and treatment principles for ADHD among college students. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15, 303–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-012-0121-z

Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., & Lappegård, T. (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behavior. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 207–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00045.x

Grace-Odeleye, B., & Santiago, J. (2019). A review of some diverse models of summer bridge programs for first-generation and at-risk college students. Administrative Issues Journal: Education Practice and Research, 9, 35–47. https://doi.org/10.5929/9.1.2

Greenwald-Mayes, G. (2002). Relationship between current quality of life and family of origin dynamics for college students with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Attention Disorders,5, 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/108705470100500403

Hall, S. S., & Zygmunt, E. (2021). I hate it here”: Mental health changes of college students living with parents during the COVID-19 quarantine. Emerging Adulthood, 9, 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968211000494

Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., & Marconi, V. C. (2017). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qualitative Health Research, 27, 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316665344

Howard, A. L., Strickland, N. J., Murray, D. W., Tamm, L., Swanson, J. M., Hinshaw, S. P., & Molina, B. S. G. (2016). Progression of impairment in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder through the transition out of high school: Contributions of parent involvement and college attendance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125, 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000100

Johnson, V. K., Gans, S. E., Kerr, S., & LaValle, W. (2010). Managing the transition to college: Family functioning, emotion coping, and adjustment in emerging adulthood. Journal of College Student Development, 51, 607–621. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2010.0022

Jones, H. A., Rabinovitch, A. E., & Hubbard, R. R. (2015). ADHD symptoms and academic adjustment to college: The role of parenting style. Journal of Attention Disorders, 19, 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054712473181

Kenyon, D. B., & Koerner, S. S. (2009). Examining emerging adults’ and parents’ expectations about autonomy during the transition to college. Journal of Adolescent Research, 24, 293, 320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558409333021

Kuriyan, A. B., Pelham, W. E., Molina, B. S. G., Waschbusch, D. A., Gnagy, E. M., Sibley, M. H., & Kent, K. M. (2013). Young adult educational and vocational outcomes of children diagnosed with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9658-z

Lamb, M. E., & Lewis, C. (2011). The role of parent-child relationships in child development. In M. H. Bornstein, & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental Science: An Advanced Textbook (6th ed.).). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Maitland, T. L., & Quinn, P. O. (2011). Ready for take-off: Preparing your teen with ADHD or LD for college. Magination Press.

Markel, C., & Wiener, J. (2014). Attribution processes in parent-adolescent conflict in families of adolescents with and without ADHD. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 46, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029854

Meaux, J. B., Green, A., & Broussard, L. (2009). ADHD in the college student: A block in the road. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(3), 248–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01349.x

Meinzer, M. C., Hill, R. M., Petit, J. W., & Nichols-Lopez, K. A. (2015). Parental support partially accounts for the covariation between ADHD and depressive symptoms in college students. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 37, 247–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-014-9449-7

Meinzer, M. C., Oddo, L. E., Garner, A. M., & Chronis-Tuscano, A. (2021). Helping college students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder SUCCEED: A comprehensive care model. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 6(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2020.1796548

Nelson, L. J., Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Nielsen, M. G. (2015). Is hovering smothering or loving? An examination of parental warmth as a moderator of relations between helicopter parenting and emerging adults’ indices of adjustment. Emerging Adulthood, 3(4), 282–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696815576458

Nelson, L. J., & Walker (2013). Flourishing and floundering in emerging adult college students. Emerging Adulthood, 1(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696812470938

Nigg, J. T. (2005). Neuropyschologic theory and findings in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: The state of the field and salient challenges for the coming decade. Biological Psychiatry, 57, 1424–1435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.011

Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Nelson, L. J. (2012). Black hawk down?: Establishing helicopter parenting as a distinct construct from other forms of parental control during emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 1177–1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.03.007

Padilla-Walker, L. M., Son, D., & Nelson, L. J. (2021). Profiles of Helicopter parenting, parental warmth, and Psychological Control during emerging Adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 9(2), 132–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818823626

QSR International (2018). NVivo (Version 12). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

Rev, T. (2018). https://www.rev.com/transcription

Sacchetti, G. M., & Lefler, E. K. (2017). ADHD symptomology and social functioning in college students. Journal of Attention Disorders, 21, 1009–1019. https://doi.org/10.1177/77/1087054714557355

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd edition) SAGE Publications.

Sibley, M. H., Campez, M., Perez, A., Morrow, A. S., Merrill, B. M., Altszuler, A. R., Coxe, S., & Yeguez, C. E. (2016). Parent management of organization, time management, and planning deficits among adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38, 216–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-015-9515-9

Sibley, M. H., Ortiz, M., Gaias, L. M., Reyes, R., Joshi, M., Alexander, D., & Graziano, P. (2021). Top problems of adolescents and young adults with ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.02.009

Sibley, M. H., Ross, J. M., Gnagy, E. M., Dixon, L. J., Conn, B., & Pelham, W. E. (2013). An intensive summer treatment program for ADHD reduces parent-adolescent conflict. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment, 35, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-012-9314-5

Sibley, M. H., & Yeguez, C. E. (2018). Managing ADHD at the post-secondary transition: A qualitative study of parent and young adult perspectives. School Mental Health, 10, 352–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9273-4

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretive phenomenological analysis: Theory, method, and analysis. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Stevens, A. E., Canu, W. H., Lefler, E. K., & Hartung, C. M. (2019). Maternal parenting style and internalizing and ADHD symptoms in college students. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 260–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1264-4

Stevens, A.E., Hartung, C.M., Shelton, C.R., LaCount, P.A., & Heaney, A. (2019). The effects of a brief organization, time management, and planning intervention for at-risk college freshmen. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 4(2), 202–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2018.1551093

Weiss, M. D. (2000). Weiss Functional Impairment Rating Scale (WFIRS) Self-Report. Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia. Retrieved from naceonline.com/AdultADHDtoolkit/assessmenttools/wfirs.pdf

Wilmshurst, L., Peele, M., & Wilmshurst, L. (2011). Resilience and well-being in college students with and without a diagnosis of ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 15, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054709347261

Zylowska, L., & Mitchell, J. T. (2021). Mindfulness for adult ADHD: A clinician’s guide. The Guilford Press.

Funding

This study was funded by the Dept of Psychology at the University of Wyoming and the Routh Dissertation Grant from Division 53 of the American Psychological Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Research involving human participants

All study procedures are in accordance with the ethical standards in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments and were approved by the university Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent

Participants completed written informed consent forms explaining the nature of the study, the potential risks and benefits of their participation, and that they would withdraw their participation at any time without penalty.

Conflicts of Interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A

Appendix A

Open-Ended Interview Question Protocol

-

1.

When were you diagnosed with ADHD? What was that like for you? What does having ADHD mean to you?

-

2.

How has having ADHD impacted your transition from high school to college?

[If participants do not discuss a wide range of areas of impairment, prompt about the domains from the Weiss Impairment Rating Scale: family, work, school, self-concept, social, life skills and risky behaviors.]

-

3.

Tell me about your relationship with your parents

[If participant needs a prompt: Tell me about the last few text exchanges or phone calls you have had with your parents.]

-

4.

How has attending college impacted your relationship with your parents?

-

5.