Abstract

This study used the instructional humor processing theory to test how different humor subtypes employed by teachers (course-related, course-unrelated, self-disparaging, other-disparaging) relate to students’ well-being, sense of belonging, and engagement. The participants comprised 395 students (boys = 106; girls = 270; other = 8; NA = 11) (secondary school students = 291; primary school students = 97, NA = 7) from five public school boards located in rural areas, and one private secondary school situated in an urban area (Mage = 14.11) with a proportion of 93% speaking French at home. Correlational and structural equation modeling methods were used to analyze these relationships. Results showed that only humor related to course content (positive association) and other-disparaging humor (negative association) were significantly associated with the sense of belonging, which, in turn, was positively associated with a cognitive, affective, and behavioral engagement. Results also showed that only course-related humor (positive association) and unrelated humor (negative association) were significantly associated with students’ emotional well-being, which, in turn, was positively associated with cognitive and affective engagement. As far as this study is concerned, humor in the classroom should be course-related when it comes to supporting students’ emotional well-being, sense of belonging, and engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Classroom management is a challenging task for teachers (Emmer & Sabornie, 2015; St-Amand et al., 2021b), a multifaceted endeavor that is far more complex than just establishing classroom rules. Overall, it is about time, space, material, codes, procedures and routines, curriculum, effective planning and assessment, observation, self-evaluation, and, more importantly, warm, stimulating, and supportive interactions (Emmer & Sabornie, 2015). Practically speaking, classroom management should seek to remove barriers between students and learning (Debbag & Fidan, 2020; Emmer et al., 2003) and favor their motivation, engagement, and learning through effective supervision (Archambault & Chouinard, 2016), while seeking to elicit student cooperation (Evertson et al., 1983). Therefore, it requires effective practices that create a classroom atmosphere that nurtures interest in learning (Rambe & Harahap, 2023; Snyder, 1998). The present study is interested in teachers’ use of humor (e.g., course-related humor, course-unrelated humor, self-disparaging humor, other-disparaging humor) and its association with students’ emotional well-being, sense of school belonging, and school engagement.

Humor in classroom management

As a well-established pedagogical practice that has been recognized for several decades in classroom management (Banas et al., 2011; St-Amand et al., 2021a), teacher humor seems to favor positive social interactions in the classroom, while evolving in terms of understanding as the children mature (Martin, 2010); in fact, students of all ages identify humor as one of the characteristics they value most in a teacher (Archambault & Chouinard, 2016; Cefai & Cooper, 2010). Researchers suggested that humor can harm (if misused) or strengthen social relationships between students and teacher; in addition, humor is thought to help students and teachers feel good and closer together (Friedman & Kuipers, 2013; Ho, 2016). This strategy is extensively used to establish or restore authority, as well as to help students adopt the values of the school code of conduct (Garner, 2006). Research has indicated that teachers’ use of humor is significantly associated with students’ motivation (Conkell et al., 1999; Luo et al., 2023), classroom and school climate (Kosiczky & Mullen, 2013), and the quality of social relations (AbdAli et al., 2016). Teachers’ humor makes it easier for students to learn difficult course content (Abdulmajeed & Hameed, 2017; Özdemir, 2017) and to succeed (Abdulmajeed & Hamed, 2017; Al-Duleimi & Aziz, 2016). Researchers have also noted an increase in students’ school engagement when teachers use humor judiciously (Hoad et al., 2013). On the teacher side, humor is reported to provide increased job satisfaction while also being a strategy that can be used to reduce teacher stress (Booth-Butterfield et al., 2007; Mawhinney, 2008). In their systematic review of the literature, Banas et al. (2011) noted that teacher humor is positively associated with the quality of teacher feedback, positive student emotions, positive perceptions of the school environment, and positive teacher perceptions. In other fields of research, meta-analyses have indicated that humor has a positive influence on workplaces (Mesmer-Magnus et al., 2012), communication (Walter et al., 2018), romantic relationships (Hall, 2017), media (Eisend, 2009), and within the field of psychology in general (Mendiburo-Seguel et al., 2015). Although a considerable amount of literary, linguistic, philosophical, communication, educational, and psychological work has been devoted to it, humor eludes any precise definition (Derouesné, 2016; Tanay et al., 2013) but generally involves a perceptual dimension (Banas et al., 2011; Martin, 2010). For example, Martin (2010) argued that humor constitutes a generic term with a generally positive, socially desirable connotation that refers to the perception of what people say or do as funny, and in a context where humor elicits joy and laughter. Although humor is a fundamental element of human communication, the concept of humor is often used inappropriately. As Tanay et al. (2013) pointed out, humor is often confused with concepts such as “joke,“ “laughter,“ or even “wit.“ As for the way it is defined: “Humor is not a unidimensional concept; instead, there are a variety of types that instructors may employ in their classrooms including: nonverbal humor, jokes, unplanned humor, self-disparaging humor, and aggressive humor (Goodboy & Bolkan, 2015)” (p. 46). To the best of our knowledge, the only conceptual study on the concept of humor in classroom management was conducted by St-Amand et al. (2021a), who highlighted the complex nature of this practice by proposing a general definition of teacher humor in classroom management contexts:

Whether planned or spontaneous, humor in the classroom is a skill displayed by the teacher and a form of communication containing very specific objectives, such as wanting to improve the classroom climate, to reduce students’ anxiety, to resolve conflicts, to improve and maintain social ties, to encourage school engagement, and, ultimately, to support students’ academic achievement. Much more than a unique pedagogical approach that can be modeled from one individual to another, teachers’ humor is characterized by a subjective and personal character that is specific to each teacher. When effectively conducted, teachers’ humor elicits positive emotional and behavioral responses from students. (St-Amand et al., 2021a, p. 120)

Theoretical framework and literature review

Drawing on several theoretical perspectives from the field of psychology (Fave et al., 1996; Zillmann & Cantor, 1996), Wanzer et al. (2010) developed a theory adapted to the educational context (instructional humor processing theory) that attempts to explain the complex processes occurring in the relationship between teacher humor and student learning. This theory allows us to examine and better interpret how teacher humor is processed and perceived by students. According to this theory, students must first recognize an incongruity in the teacher’s message and then interpret and resolve it. If the incongruity is not resolved, the student will not perceive the humorous message and as a result may be distracted or confused. However, if the student resolves the incongruity, he or she may perceive a humorous message and laughter may result; in this context, the nature of the humorous message and how it is interpreted emotionally determines whether or not humor facilitates motivation and learning.

Teachers’ humor and students’ emotional well-being

Several studies have used the instructional humor processing theory in recent years. The majority of these have been conducted at the university level (Bolkan et al., 2018; Bolkan & Goodboy, 2015; Goodboy et al., 2015; Imlawi et al., 2015; Tsukawaki & Imura, 2020; Wanzer et al., 2010) while fewer have been conducted in high school or elementary settings (Bieg et al., 2017, 2019; Ziyaeemehr, 2011). These studies have attempted to better understand the relationship between teacher humor and student emotions (Bieg et al., 2017, 2019; Wanzer et al., 2010), teacher humor and student learning (Bolkan et al., 2018; Tsukawaki & Imura, 2020), and teacher humor and school engagement (Bolkan & Goodboy, 2015; Goodboy et al., 2015; Imlawi et al., 2015), and the reasons why teachers refrain from using humor in the classroom (Ziyaeemehr, 2011). From these studies, humor related to course content was found to have a significant and positive association with enjoyment of being in class, while being negatively associated with boredom and anger (Bieg et al., 2019). Among high school students, Bieg et al. (2017) also reported a significant and positive association between humor related to course content and enjoyment of being in class, as well as a negative association with boredom. Furthermore, these results suggested that the more course content-related humor the teacher uses, the less anxiety students experience. According to Bieg et al. (2017), humor unrelated to course content and self-disparaging humor are not predictors of these positive emotions. Among college students, Wanzer et al. (2010) also determined that humor related to course content displays a positive relationship with learning-related emotions. In light of these studies conducted specifically with high school, elementary school, and college students, it can be concluded that humor related to course content appears to be closely linked to students’ overall emotional well-being.

Students’ emotional well-being and engagement

Although there is no consensus regarding the definition of emotional well-being, it does include psychological dimensions such as the presence of positive emotions (Liddle & Carter, 2015). Lately, many studies have, therefore, increased the importance of the mediating role of emotional well-being (including emotions such as enjoyment, happiness, or a general measure of positive emotions) as well as its direct influence on school engagement. At the elementary level, students’ feelings such as happiness (Kwon et al., 2017) and enjoyment (Reschly et al., 2008) have been significantly and positively associated with school engagement. Enjoyment has also mediated the relationship between teacher support and school engagement (Liu et al., 2018). Chen et al. (2020) found that student enjoyment in the classroom mediated the relationship between the teachers’ communication skills and students’ engagement. At the high school level, McKeering et al. (2021) highlighted a significant and positive association between emotional well-being and engagement. Gong and Bergey (2020) found that positive emotions completely mediate the relationship between student efficacy and engagement, while Liu et al. (2021), for their part, indicated that teacher support can be positively and significantly associated with behavioral engagement via enjoyment. As for age groups, older students (12 to 14 years old) showed lower emotional well-being than younger groups (10 years old) (McKeering et al., 2021). Among college students, positive emotions (time 1) were shown to influence engagement (time 2) significantly and positively. The association between teacher enthusiasm and student engagement was found to be mediated by emotional well-being (boredom and enjoyment) (Dewaele & Li, 2021). With regard to the relationship between student self-control and behavioral and emotional engagement, positive emotion was identified as a mediator (King & Gaerlan, 2014).

Teachers’ humor and students’ sense of school belonging

The sense of school belonging is a fundamental component of student engagement and is generally stronger for females than for males, while varying from one grade to another (Faircloth & Hamm, 2005; Finn, 1989; Goodenow & Grady, 1993; Korpershoek et al., 2020; Sari, 2013; Smith et al., 2020; St-Amand et al., 2020a). It is also a multidimensional and complex concept comprising several definitional attributes. Students must: (1) feel a positive emotion toward school; (2) maintain positive social relationships with their peers and teachers; (3) perceive a synergy (harmonization) and a certain similarity with the members of the group; and (4) become actively involved in the school environment (St-Amand et al., 2017b). Several factors contribute to creating and structuring students’ sense of school belonging (Ahmadi et al., 2020; Allen et al., 2018; Janosz et al., 1998). Allen et al. (2018) categorized the determinants of the sense of school belonging into factors at the individual level (e.g., personality, self-esteem, social skills, motivation, optimism), the micro level (e.g., social relationships, parents, peers, teacher support, presence of friends), and the meso level (e.g., extracurricular activities, discipline in the classroom, the climate of justice, the climate of security). Teacher humor was identified as a very important pedagogical strategy that builds students’ sense of school belonging (Certo et al., 2003; Cothran & Ennis, 2000; FitzSimmons, 2006; Glaser & Bingham, 2009; Hillman, 2011; LoVerde, 2007; Ozer et al., 2008) and makes students want to attend class (Seaman, 2017). Teacher humor is a pedagogical strategy that positively changes the classroom atmosphere (Cooper et al., 2018) and helps in developing a good social network (Kibler et al., 2019); Cooper et al. (2018) showed that, on average, teacher humor slightly increases classroom belonging for 37.8% of respondents, and a great deal in 42.2% of respondents (sample = 1637 college students). Other researchers reported that teacher humor at T1 is a significant predictor of students’ sense of belonging at T2 and T3 (sample = 335 college students) (Sidelinger et al., 2012). On the flip side, a teacher who never uses humor could also contribute to students’ sense of belonging. As Stuart and Rosenfeld (1994, p. 93) explained:

The one benefit of teachers being perceived as humorless or as using hostile humor exclusively relates to affiliation in the classroom. Students with these two types of teachers are more likely to increase interaction among themselves, perhaps either to relieve boredom or to unite and share perceptions of a common “enemy.“

Students’ sense of school belonging and engagement

Developing student engagement in school and preventing disengagement is a major concern for teachers (Archambault et al., 2019; Mbikayi & St-Amand, 2017; St-Amand, 2016, 2018; St-Amand et al., 2017a, b, c). One of the overriding elements that increases school disengagement is a low sense of school belonging (Allen et al., 2023; Archambault et al., 2022; Christenson & Thurlow, 2004). Conversely, scientists have suggested that a high sense of school belonging facilitates school engagement (Fong Lam et al., 2015; Hughes et al., 2015; Janosz et al., 1998). Seminal work by Wehlage et al. (1989) and Goodenow (1993a, 1993b) showed that when students feel supported by peers and adults in their learning environment (school) and identify with (or feel included in) that environment, they tend to place more value on learning and achieving. For Goodenow (1993b), these elements form the basis of what is known as “school climate” or a “sense of school belonging.” Previous studies clearly indicated a positive association between the sense of school belonging/climate and the quality of school engagement (Janosz et al., 1998; St-Amand et al., 2020b). Indeed, researchers have demonstrated the association between the sense of school belonging and several motivational variables (Korpershoek et al., 2020). Some studies found a positive and significant association between the sense of school belonging and the three forms of school engagement (cognitive, affective, and behavioral) (Korpershoek et al., 2020; St-Amand et al., 2020b, 2021a). Other theoretical studies highlighted the positive association between students’ sense of school belonging and school engagement (Connell et al., 1994; Newmann et al., 1992). Pioneers in the study of the sense of school belonging highlighted that such an association started in the late 1980s. Connell et al. (1994) suggested a direct relationship between a sense of school belonging and school engagement, which, in turn, positively influences academic achievement. In developing their theoretical model, Newmann et al. (1992) also pointed out the significant and positive relationship between the sense of belonging and school engagement, specifying that belonging directly influences school engagement. Finn (1989) developed a dynamic model explaining the links between the sense of school belonging and school engagement. This model states that participation in activities is a critical component of school success, which, in turn, contributes to the development and structuring of the sense of school belonging. Also, in the late 1980s, Wehlage et al. (1989) focused on pedagogical practices and the effectiveness of the school in promoting education. From this theoretical perspective, the relationship between the sense of school belonging and school engagement is bidirectional in nature, which is theoretically different from the theoretical evidence presented thus far.

Rationale of the study and hypotheses

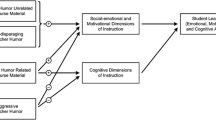

As discussed in the previous sections, researchers have attempted to investigate the relationship between teacher humor and school engagement through the lens of the instructional humor processing theory (Bolkan & Goodboy, 2015; Goodboy et al., 2015; Imlawi et al., 2015). These studies were conducted among adults and college students, not with elementary and high school students, and, to the best of our knowledge, only Bolkan and Goodboy’s (2015) study considers the affects as a mediating variable in the relationship between teacher humor and school engagement. Using structural equation modeling, their work indicates that the relationship between teacher humor and school engagement is mediated by students’ affects related to the course and the teacher, as well as the recommended course behaviors. In addition to not taking into consideration other types of school engagement (cognitive, affective, behavioral) (Fredericks et al., 2004), these researchers do not account for emotions that underlie school engagement: students’ sense of school belonging and emotional well-being. The present study is intended to contribute to the work of Bolkan and Goodboy (2015) in that teacher humor – that is, the ability to make the learning environment more effective – may influence students’ emotional well-being and a basic need such as the sense of school belonging, which, in its definition, carries a great deal of emotional significance: “Belonging also refers to positive emotions, which could be described as emotional attachments, more precisely to a feeling of intimacy, feeling part of a supportive environment, and a sense of pride in the school” (St-Amand et al., 2017a, p. 14). The present study, therefore, seeks to determine how teachers’ use of humor (e.g., course-related humor, course-unrelated humor, self-disparaging humor, other-disparaging humor) relates to students’ sense of school belonging, emotional well-being, and engagement, and to test for invariance across elementary and high school students and across males and females. Derived from the instructional humor processing theory, Fig. 1 illustrates the determinants of school engagement from the different groups of predictor variables; one of these groups (sense of school belonging) is directly linked with the different forms of school engagement, while other variables (adequate and inadequate humor) indicate indirect links with school engagement.

The organization of these associations within the model leads us to formulate six research hypotheses:

H1

The different types of teacher humor (course-related humor, course-unrelated humor, self-disparaging humor, other-disparaging humor) have a positive influence on the sense of school belonging.

H2

The sense of school belonging has a positive influence on the three types of school engagement (cognitive, affective, and behavioral).

H3

The different types of teacher humor (course-related humor, course-unrelated humor, self-disparaging humor, other-disparaging humor) have a positive influence on students’ emotional well-being.

H4

Students’ emotional well-being has a positive influence on the three types of school engagement (cognitive, affective, and behavioral).

H5

The association between the different types of teacher humor and the sense of school belonging is stronger for high school students than for elementary school students.

H6

The association between the different types of teacher humor and the sense of school belonging is stronger for females than for males.

Methodology

Sample

The participants comprised 395 students (boys = 106; girls = 270; other = 8; NA = 11) (secondary school students = 291; primary school students = 97, NA = 7) from five public school boards located in rural areas, and one private secondary school situated in an urban area (Mage = 14.11) with a proportion of 93% speaking French at home. The data collection took place during the months of April and May, 2021. Students were instructed to respond to all questions online and to keep their answers confidential. It took less than 15 minutes to complete the questionnaire. The questionnaire was comprised of 40 items, allowing for the measure of nine different latent constructs. Participants had to indicate their level of agreement regarding each item on a Likert scale. To measure the variables in this study and the quality of certain characteristics of the school environment, the authors used only part of the Questionnaire sur l’environnement socioéducatif (QES-secondaire) [Questionnaire on the socio-educational environment (QES-high school)], namely the sense of school belonging, and the cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions of school engagement (Janosz & Bouthillier, 2007). To measure teachers’ adequate and inadequate humor, we used the Teacher Humor Scale based on the work of Wanzer et al. (2006) and validated by Frymier et al. (2008). It allowed us to measure variables such as course-related humor, course-unrelated humor, self-disparaging humor, and other-disparaging humor. Finally, emotional well-being was measured using the General Well-Being Scale (Perreault, 1989).

Measures

To measure the emotional dimension of the sense of school belonging, we used a five-item subscale that assessed students’ sense of school belonging (items: “I feel proud to be a student at my school,” “I feel like I’m really part of my school,” “I like my school,” “I am happy to be back to school after a long school break,” and “I wish I were in a different school”) (Janosz & Bouthillier, 2007). The last item was reverse coded, and item scores were averaged to generate a score reflecting school belonging (M = 4.54, SD = 1.77, α = 0.86) (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree).

Self-reported items were used to measure school engagement. These items represent three dimensions converging toward a more global concept measuring school engagement. In this study, the authors consider each of these three dimensions in a unique way, as suggested by most scholars in the field of school motivation (Fredricks et al., 2004). First, behavioral engagement measures positive behaviors such as the following of classroom rules and adherence to classroom norms, as well as the absence of disturbing behaviors (Fredricks et al., 2004; Martins et al., 2022). To measure behavioral engagement, participants responded to the four-item subscale that assessed this dimension (Janosz & Bouthillier, 2007) (items: “In the past 12 months, have you missed school without a valid excuse?”, “In the past 12 months, have you missed a class while you were in school?”, “In the past 12 months, have you disturbed your class on purpose?”, and “In the past 12 months, have you responded to a teacher by being impolite?”) (M = 5.25, SD = 0.96, α = 0.60) (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). Second, affective engagement in school tasks refers to feelings, interest, perceptions, and attitudes toward school (Fredricks et al., 2004). To measure affective engagement, participants responded to the five-item subscale that assessed this dimension (Janosz & Bouthillier, 2007) (items: “I like school,” “I have fun at school,” “What we learn in class is interesting,” “I am very enthusiastic when the job to be done is quite difficult,” and “Often I don’t feel like stopping work at the end of a course”) (M = 3.95, SD = 1.13, α = 0.88) (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). Third, the cognitive dimension of school engagement relates to the psychological investment in learning school subjects (Fredricks et al., 2004). To measure cognitive engagement, participants responded to the three-item subscale that assessed this dimension (Janosz & Bouthillier, 2007) (items: “I am willing to make efforts in mathematics,” “I am willing to devote time to mathematics,” and “I want to learn more about what we do in mathematics”) (M = 4.30, SD = 1.4, α = 0.92) (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree).

To measure teacher humor, we used the Frymier et al. (2008) scale originally developed to measure teacher humor in college classes. We translated the instrument into French and adapted it for an elementary and secondary school context by removing a subscale (offensive humor) that was not appropriate for elementary and high school students (e.g., makes references to drinking or getting drunk in a humorous way, talks about drugs or other illegal activities in a humorous way). We preserved 21 items to measure four humor subscales: course-related humor (e.g., uses humor related to the course material) (M = 3.73, SD = 1.13, α = 0.86), course-unrelated humor (e.g., tells jokes unrelated to the course content) (M = 3.63, SD = 1.38, α = 0.84), self-disparaging humor (e.g., makes fun of him/herself in class) (M = 3.43, SD = 1.32, α = 0.78), and other-disparaging humor (e.g., picks on students in class for their intelligence) (M = 1.52, SD = 0.77, α = 0.86). We asked students to rate the degree of agreement regarding each item based on a six-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree).

To measure emotional well-being, psychological well-being scales are used, sometimes called “happiness scales.“ The Santé Québec survey used an abbreviated and considerably modified version of the General Well-Being Scale (Perreault, 1989), which has been referred to as the “Bien-Être Santé Québec” (BESQ) [Québec’s Health and Well-Being]. Seven dimensions of emotional well-being are explored: energy (e.g., I felt full of spirit and energy), control of emotions (e.g., it was easy for me to control my emotions), general mood (e.g., I felt in a good mood and light-hearted), interest in life (e.g., a lot of interesting things happened), stress (e.g., I felt sufficiently relaxed), health perception (e.g., I have not had any problems with my health), and emotional isolation (e.g., I felt loved and appreciated). For each of the dimensions, one item explores the positive affect in question; the instrument therefore has seven items (M = 3.88, SD = 1.10, α = 0.83). We asked students to rate the degree of agreement regarding each item based on a six-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree).

Preliminary analyses

First, we conducted preliminary analyses, which indicated an acceptable distribution of the data, homogeneity of variance, and the absence of multicollinearity. Following initial data processing, we removed a few outliers. We dealt with the missing data by proceeding with a technique called “maximum likelihood” (EM or expectation maximization). Since our data showed a very low percentage of missing data (5%), this technique correctly reflected the uncertainty of missing values and preserved important aspects of distributions (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013).

Main analyses

Structural equation modeling analyses (SEM) were performed to test the hypothesized associations presented in Fig. 1. A first hypothetical model is usually tested. To examine whether this model adequately fits the data, different fit indices are needed: chi-square (χ2), CFI, TLI, and RMSEA. As Hu and Bentler (1999) suggested, a good model should provide acceptable results on various fit tests. The global adjustment index used is χ2 (also called the chi-square likelihood ratio or generalized likelihood ratio). A nonsignificant value at the χ2 index generally reflects a good fit (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Other indices have been used such as the CFI (comparative fit index) and the TLI (Tucker–Lewis index). Values greater than or close to 0.95 for these two indices indicate an appropriate fit of the data (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2016). The RMSEA (root mean square residual error of approximation) requires a value of 0.06 or less to be considered an adequate data fit (MacCallum et al., 1996).

From the various adjustment indices obtained while testing the hypothetical model, the modification indices (Lagrange multiplier) were used to improve the adjustment of the model; in modifying the hypothetical model, we made sure we respected the logic and consistency of the underlying theory (Perry et al., 2015). The preferred estimation technique in this research is maximum likelihood. Maximum likelihood is a commonly used estimation method for this type of analysis. According to Kline (2016), this method is unbiased in addition to being efficient and consistent.

In order to explore whether the associations under study varied according to the grade level of the students and their gender, we used a multigroup approach, as advocated by Byrne (2016), in a confirmatory approach to comparing models. This invariance procedure confirms the equality (or not) of the estimated parameters. To achieve this, we imposed equality constraints on the parameters of the models to check whether the models are equivalent according to the school grade of the students (primary school/high school) and their gender. These statistical procedures are clearly explained by Byrne (2016). Two indices are used to measure the invariance of the parameters: the chi-square difference and the CFI difference (Byrne, 2016). Since the use of both methods is still the subject of debate in the scientific community, and that “it is hoped that statisticians engaged in Monte Carlo simulation research related to structural equation modeling will develop more efficient and useful alternative approaches to this decision-making process in the near future” (Byrne, 2016, p. 307), we opted to report the X²-difference test knowing that more work needs to be conducted in this area (Byrne, 2016). To perform these statistical analyses, STATA software (version 17) was used.

Results

Descriptive and correlation statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables included in the model under study and the correlations between them. The means vary from 1.52 (other-disparaging humor) to 5.25 (behavioral engagement). All correlations were significant (p < .01), except for the associations between course-unrelated humor and the sense of school belonging (0.08, p = .11); course-unrelated humor and cognitive engagement (-0.06, p = .22); course-unrelated humor and affective engagement (-0.01, p = .89); self-disparaging humor and behavioral engagement (-0.01, p = .91); self-disparaging humor and affective engagement (0.06, p = .25); self-disparaging humor and cognitive engagement (0.03, p = .57); other-disparaging humor and cognitive engagement (-0.01, p = .88); and other-disparaging humor and course-related humor (0.03, p = .56). The significant correlations varied from weak (-0.08, p < .01) to strong (0.69, p < .01). Five variables displayed negative correlations with other-disparaging humor: well-being (-0.08, p < .01), the sense of school belonging (-0.21, p < .01), behavioral engagement (-0.21, p < .01), affective engagement (-0.18, p < .01), and cognitive engagement (-0.01, p < .01). Three variables displayed negative correlations with course-unrelated humor: behavioral engagement (-0.16, p < .01), affective engagement (-0.01, p < .01), and cognitive engagement (-0.06, p < .01). Our results showed that all other correlations were positive.

Structural equation modeling

The results of the hypothetical framework (confirmatory factor analysis) (the latent factors under study) indicated a close acceptable fit with the data (X2[999] = 2361.850, p < .000; RMSEA = 0.059 (95%CI = [0.056, 0.062]); CFI = 0.865; AIC = 47641.951). Specifically, although the CFI value was slightly below the desired threshold of 0.90 (CFI = 0.865), the RMSEA test was below the threshold of 0.08, which is acceptable for some researchers (RMSEA = 0.059) (Hooper et al., 2008). Kenny & McCoach (2003) pointed out that the CFI fit index tends to deteriorate as the number of variables increases. This issue is quite common when validating complex models with many variables. Since the present structural equation model has nine latent variables and 57 observed variables, the model fit was considered adequate in the circumstances.

In Fig. 2, we illustrate the basic hypothetical model for examining the associations between our latent variables. More precisely, the latent variables, the sense of school belonging (Belonging) and well-being (WB), mediate the relationships made up of the different types of teacher humor (Related = humor related to course content, Unrelated = humor unrelated to course content, Selfdisp = self-disparaging humor, Otherdisp = other-disparaging humor) in order to explain the three types of school engagement (CogEng = cognitive engagement, AffEng = affective engagement, BehEng = behavioral engagement). Because our initial hypothetical model (Model 1) did not fit well according to the criteria mentioned above, we carried out a certain number of modifications to improve the model fit.

Subsequent models

With regard to the modification indices, five links were removed (well-being and behavioral engagement; self-disparaging humor and the sense of school belonging; self-disparaging humor and well-being; other-disparaging humor and well-being; unrelated humor and the sense of school belonging) because they were not significant. One association was added between the sense of school belonging and well-being because it was significant. In addition, a few error terms were correlated (57 and 59; 59 and 60; 57 and 65; 65 and 66; 64 and 65; 46 and 47; 43 and 44; 40 and 41; 84 and 85; 85 and 89; 89 and 91). In Model 2, the fit indices were all satisfactory (see Table 2). In the final model (Model 2), five nonsignificant associations were removed; all the other links of Model 1 were preserved, and one was added, because they were significant. Hence, the results suggest that course-related humor has a significant and positive association with the sense of school belonging (SE = 0.05, p < .001, β = 0.47, 95%CI (0.38 – 0.57)) and well-being (SE = 0.09, p < .001, β = 0.41, 95%CI (0.30 – 0.53)), that unrelated humor has a significant and negative association with well-being (SE = 0.05, p < .001, β = - 0.14, 95%CI (-0.24 – - 0.04)), and that other-disparaging humor has a significant and negative association with the sense of school belonging (SE = 0.05, p < .001, β = - 0.24, 95%CI (-0.33 – - 0.14)). For its part, the sense of school belonging has a significant and positive association with well-being (SE = 0.06, p < .001, β = 0.28, 95%CI (0.16 – 0.39)), and the three types of school engagement, namely cognitive engagement (SE = 0.06, p < .001, β = 0.26, 95%CI (0.17 – 0.40)), affective engagement (SE = 0.04, p < .001, β = 0.64, 95%CI (0.56 – 0.72)), and behavioral engagement (SE = 0.06, p < .001, β = 0.48, 95%CI (0.35 – 0.60)). Compared to the sense of school belonging, well-being has a significant and positive association with only two types of school engagement, namely affective engagement (SE = 0.04, p < .001, β = 0.35, 95%CI (0.26 – 0.43)) and cognitive engagement (SE = 0.06, p < .001, β = 0.29, 95%CI (0.17 – 0.40)). Additionally, the indirect association path coefficient between other-disparaging humor and the different types of school engagement and well-being through the sense of school belonging mediation was significant (p < .001), indicating that belonging fully mediates the relationships under study. Second, the indirect association path coefficient between unrelated humor and the different types of school engagement (affective and cognitive engagement) through well-being mediation was significant (p < .001), indicating that well-being fully mediates the relationships under study. Finally, the indirect association path coefficient between course-related humor and the three types of school engagement (behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement) through belonging mediation and well-being mediation was significant (p < .001), indicating that belonging and well-being fully mediate the relationships under study except for the association between related humor, well-being, and behavioral engagement.

Invariance analysis

A multigoup analysis was conducted with an X²-difference test to determine whether the associations between course-related humor and the sense of school belonging, and other-disparaging humor and the sense of school belonging, were invariant regarding gender. The X²-difference test was statistically nonsignificant between other-disparaging humor and the sense of school belonging (p = .867, p < .05), meaning that there is no difference between males and females. However, the X²-difference test was significant between course-related humor and the sense of school belonging (p = .04, p < .05), meaning that there is a difference concerning males and females. Further analysis determined that it is significantly stronger for females (β = 0.32) than for males (β = 0.24) (Hypothesis 6). In regard to students attending elementary schools and high schools, the X²-difference test determined that the association between course-related humor and the sense of school belonging was not significant (p = .32, p < .05), meaning that there is no difference between high school students and elementary school students. The X²-difference test also indicated that there is no difference between elementary school students and high school students regarding the association between other-disparaging humor and the sense of school belonging (p = .09, p < .05), making this association invariant regarding grades (Hypothesis 5).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to determine how teachers’ use of humor (e.g., course-related humor, course-unrelated humor, self-disparaging humor, other-disparaging humor) relates to students’ sense of school belonging, engagement, and emotional well-being, and to test for invariance across elementary and high school students as well as across males and females. Our hypotheses were based on the instructional humor processing theory (IHPT) derived from the work of Wanzer et al. (2010), as well as on many studies exploring teacher humor, students’ sense of school belonging, and school engagement (Bolkan & Goodboy, 2015; Goodboy et al., 2015; Imlawi et al., 2015). Although Bolkan and Goodboy (2015) considered students’ affects as a mediator of the relationship between teacher humor and engagement, no study has explored jointly the sense of school belonging and emotional well-being. Our results are a contribution to the IHTP (Wanzer et al., 2010) and indicate, for the first time, how different types of humor can influence the sense of school belonging, engagement, and emotional well-being, and thus answer research questions that have not been empirically studied.

The first hypothesis assumed that the different types of teacher humor (course-related humor, course-unrelated humor, self-disparaging humor, other-disparaging humor) were positively associated with the sense of school belonging. This hypothesis was partially supported as not all types of humor were associated with the sense of belonging. Our results indicated that, among the four types of teacher humor that we measured, only humor related to course content (positive significant) and other-disparaging humor (negative significant) had a significant association with the sense of school belonging, which can be categorized as adequate and inadequate humor, respectively (Frymier et al., 2008). The relation between course-related humor and the sense of school belonging may be due to the emotional component of the latter. Researchers have suggested that belonging may refer to having emotional attachments, feeling intimacy, feeling needed, feeling useful and supported, feeling proud to attend the institution, and, finally, feeling good (St-Amand et al., 2017c). The work of Baumeister and Leary (1995) and the more recent work of St-Amand et al. (2017b) support the idea that the presence of a sense of school belonging involves positive emotions such as happiness, satisfaction, enthusiasm, and a state of calm. While course-related humor can trigger positive emotions, it is possible that other-disparaging humor (e.g., picks on students in class for their intelligence) has the opposite effect. As demonstrated by Bieg et al. (2019), teachers using humor associated with course content contributes to weakening the decrease in enjoyment and the increase in boredom and anger.

Our results also showed that the sense of school belonging was positively associated with the three types of school engagement (cognitive, affective, and behavioral) (H2), as well as with emotional well-being. These relationships can be explained by the fact that the sense of school belonging is a generator of several emotions that underlie students’ motivation to learn (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). St-Amand et al. (2020b) empirically demonstrated that the positive emotions derived from an emotion such as the sense of school belonging can partially explain the relation between belongingness and school engagement. However, it is also possible that achievement emotions may play a central role in this relationship. In recent years, researchers have documented the notion of “achievement emotions,” which are defined as “emotions that are directly linked to achievement activities or achievement outcomes”. Pekrun et al. (2002) suggested that emotions can be generated while attending school, simply by studying or completing exams. Thus, it is possible that the sense of school belonging influences achievement emotions as well as students’ emotional well-being depending on the context in which it all takes place (e.g., class-related, learning-related, and test-related emotions) and that these emotions drive school engagement.

While it is tempting to believe that all types of humor can be effective and supportive in a classroom setting (St-Amand et al., 2021a), our results clearly indicate that only humor associated with course content is effective in developing students’ sense of school belonging and emotional well-being (H3). While it appears detrimental to use other-disparaging humor, we do not consider the other two types of humor to be completely inappropriate (self-disparaging humor and course-unrelated humor). As Bieg et al. (2019) noted, the use of these two types of humor is probably not advantageous to consider in one’s instructional planning, especially for providing emotional experiences that contribute to the development of students’ sense of school belonging and emotional well-being. On the other hand, both types of humor can have other potential roles to play, such as building students’ resilience in their educational journey (Bondy et al., 2007). Clearly, more research is needed to investigate these relationships.

Except for behavioral engagement, our results showed that emotional well-being is positively and significantly associated with affective and cognitive engagement (H5). These results refer to the numerous studies that have shown that positive emotions (e.g., enjoyment) play a key role in students’ school engagement (Kwon et al., 2017; McKeering et al., 2021). The nonsignificant association between emotional well-being and behavioral engagement is likely due to the nature of the variable itself. Indeed, behavioral engagement was essentially measured from a perspective related to the adoption of norms, values, and respect toward the school’s code of life. To get a more complete picture of the phenomenon, it would be desirable to measure behavioral engagement by taking into account behaviors directly related to the learners’ effectiveness (e.g., raising a hand to ask a question, completing homework, etc.) (Nguyen et al., 2018).

Finally, we hypothesized that the association between the different types of teacher humor and the sense of school belonging is stronger for high school students than for elementary school students (H5), and stronger for females than for males (H6). Hypothesis 5 could not be validated by our data, although the understanding of teacher humor evolves as the children get older (Martin, 2010). Indeed, developmental stages do exist in the production and understanding of humor. Beginning at age 7, for instance, children discover that words can have double meanings and their jokes become more complex and varied (Nwokah et al., 2013; Sahayu et al., 2022). Most of our youngest participants were in sixth-grade classrooms, so older than seven, which is not a big difference from much of our older sample, in this case middle and high school students. The invariance of these results can therefore be explained by the nature of our sample. As for Hypothesis 6, our results indicated that the association between course-related humor and the sense of school belonging was stronger for females than for males. Across elementary, middle, and high school levels, girls are generally more engaged than boys in school (Marks, 2000) and likely more responsive to the determinants of school belonging, which may explain these results.

Conclusion

As in all studies, this one has limitations and other research avenues that we would like to highlight. First, our sample is made up of students from public schools situated in rural Canada, and one private secondary school situated in an urban area. This situation prevents us from generalizing our results in major cities across the country and among indigenous communities. Studying these relationships across different cultures would provide a more comprehensive look at the phenomenon under study (Davies, 2003; Jiang et al., 2020). Second, even though the internal consistency of our scales appeared adequate, it would have been useful to use a scale such as the PSSM (Psychological Sense of School Membership scale), which measures other dimensions of the sense of school belonging, such as the quality of social relations (St-Amand et al., 2020a). The fact that the scales were all self-reported and based on self-observations limited our view of the phenomenon. In this sense, it would be beneficial to add analytical perspectives such as observation, classroom recordings, or critical incident methods. On the question of causality, and to validate the results of the present study, it would be appropriate to conduct a study in a controlled environment with an experimental design. Third, we measured this phenomenon at a single measurement time. A longitudinal design would allow us to study the evolution of these relationships, while seeking to identify the most at-risk periods during the school year or the periods when humor has the greatest impact on students’ sense of school belonging, engagement, and emotional well-being. Fourth, as researchers have found that the level of emotional well-being varies as students age, testing for invariance regarding emotional well-being and its determinants such as teacher humor would be appropriate in future studies (McKeering et al., 2021). Finally, researchers have demonstrated that school belonging can be triggered by specific instructor characteristics, such as encouragement of student participation and quality interaction (Freeman et al., 2007). Understanding where these practices fall in relation to teacher humor would be beneficial in maximizing teaching effectiveness.

Change history

09 May 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04619-9

References

AbdAli, A., Ashur, N., Ghazi, L., & Muslim, A. (2016). Measuring students’ attitudes towards teachers’ use of humour during lessons: A questionnaire study. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(35), 52–59.

Abdulmajeed, R. K., & Hameed, S. K. (2017). Using a linguistic theory of humour in teaching English grammar. English Language Teaching, 10(2), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n2p40

Ahmadi, S., Hassani, M., & Ahmadi, F. (2020). Student- and school-level factors related to school belongingness among high school students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 741–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2020.1730200

Al-Duleimi, A. D. D., & Aziz, R. N. (2016). Humour as EFL learning-teaching strategy. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(10), 105–115.

Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

Allen, K. A., Boyle, C., Wong, D., Johnson, R. G., & May, F. (2023). School belonging as an essential component of positive psychology in schools. In A. Giraldez-Hayes, & J. Burke (Eds.), Applied positive school psychology (pp. 159–172). Routledge.

Archambault, J., & Chouinard, R. (2016). Vers une gestion éducative de la classe [Towards educational classroom management] (4th ed.). Chenelière.

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Goulet, M., Dupéré, V., & Gilbert-Blanchard, O. (2019). Promoting student engagement from childhood to adolescence as a way to improve positive youth development and school completion. In J. A. Fredricks, A. L. Reschly, & S. L. Christenson (Eds.), Handbook of student engagement interventions: Working with disengaged students (pp. 13–29). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813413-9.00002-4

Archambault, A., Janosz, M., Olivier, E., & Dupéré, V. (2022). Student engagement and school dropout: Theories, evidence, and future directions. In A. L. Reschly, & S. L. Christenson (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (2nd ed.). Springer.

Banas, J. A., Dunbar, N., Rodriguez, D., & Liu, S. J. (2011). A review of humor in educational settings: Four decades of research. Communication Education, 60(1), 115–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2010.496867

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Bieg, S., Grassinger, R., & Dresel, M. (2017). Humor as a magic bullet? Associations of different teacher humor types with student emotions. Learning and Individual Differences, 56, 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.04.008

Bieg, S., Grassinger, R., & Dresel, M. (2019). Teacher humor: Longitudinal effects on students’ emotions. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34(3), 517–534.

Bolkan, S., & Goodboy, A. K. (2015). Exploratory theoretical tests of the instructor humor–student learning link. Communication Education, 64(1), 45–64.

Bolkan, S., Griffin, D. J., & Goodboy, A. K. (2018). Humor in the classroom: The effects of integrated humor on student learning. Communication Education, 67(2), 144–164.

Bondy, E., Ross, D. D., Gallingane, C., & Hambacher, E. (2007). Creating environments of success and resilience: Culturally responsive classroom management and more. Urban Education, 42(4), 326–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085907303406

Booth-Butterfield, M., Booth-Butterfield, S., & Wanzer, M. B. (2007). Funny students cope better: Patterns of humor enactment and coping effectiveness. Communication Quarterly, 55(3), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370701490232

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Cefai, C., & Cooper, P. (2010). Students without voices: The unheard accounts of secondary school students with social, emotional and behaviour difficulties. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 25(2), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856251003658702

Certo, J. L., Cauley, K. M., & Chafin, C. (2003). Students’ perspectives on their high school experience. Adolescence, 38, 705–724.

Chen, G., Zhang, J., Chan, C. K., Michaels, S., Resnick, L. B., & Huang, X. (2020). The link between student-perceived teacher talk and student enjoyment, anxiety and discursive engagement in the classroom. British Educational Research Journal, 46(3), 631–652. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3600

Christenson, S. L., & Thurlow, M. L. (2004). School dropouts: Prevention considerations, interventions, and challenges. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(1), 36–39. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.0963-7214.2004.01301010.x.

Conkell, C. S., Imwold, C., & Ratliffe, T. (1999). The effects of humor on communicating fitness concepts to high school students. Physical Educator, 56(1), 8.

Connell, J. P., Spencer, M. B., & Alber, J. L. (1994). Educational risk and resilience in african-american youth: Context, self, action, and outcomes in school. Child Development, 65(2), 493–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00765.x

Cooper, K. M., Hendrix, T., Stephens, M. D., Cala, J. M., Mahrer, K., Krieg, A., Agloro, A. C. M., Badini, G. V., Barnes, M. E., Eledge, B., Jones, R., Lemon, E. C., Massimo, A. M., Ruberto, T., Simonson, K., Webb, E. A., Weaver, J., Zheng, Y., & Brownell, S. E. (2018). To be funny or not to be funny: Gender differences in student perceptions of instructor humor in college science courses. PLoS ONE, 13(8),e0201258. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201258

Cothran, D. J., & Ennis, C. D. (2000). Building bridges to student engagement: Communicating respect and care for students in urban high schools. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 33(2), 106–117.

Davies, C. E. (2003). How english-learners joke with native speakers: An interactional sociolinguistic perspective on humor as collaborative discourse across cultures. Journal of Pragmatics, 35(9), 1361–1385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00181-9

Debbag, M., & Fidan, M. (2020). Relationships between prospective teachers’ multicultural education attitudes and classroom management styles. International Journal of Progressive Education, 16(2), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.29329/ijpe.2020.241.8

Derouesné, C. (2016). Neuropsychologie de l’humour: une introduction – Partie 1. Données psychologiques. Gériatrie et psychologie neuropsychiatrie du vieillissement, 14(1), 95–103.

Dewaele, J. M., & Li, C. (2021). Teacher enthusiasm and students’ social-behavioral learning engagement: The mediating role of student enjoyment and boredom in chinese EFL classes. Language Teaching Research, 25(6), 922–945. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F13621688211014538.

Eisend, M. (2009). A meta-analysis of humor in advertising. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37(2), 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-008-0096-y

Emmer, E. T., Evertson, C. M., & Worsham, M. E. (2003). Classroom management for secondary teachers (6th ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

Emmer, E. T., & Sabornie, E. J. (2015). Handbook of classroom management (2nd ed.) Routledge.

Evertson, C. M., Emmer, E. T., Sanford, J. P., & Clements, B. S. (1983). Improving classroom management: An experiment in elementary school classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 84(2), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1086/461354

Faircloth, B. S., & Hamm, J. V. (2005). Sense of belonging among high school students representing 4 ethnic groups. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(4), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-5752-7

Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59(2), 117–142. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F00346543059002117.

FitzSimmons, V. C. (2006). Relatedness: The foundation for the engagement of middle school students during the transitional year of sixth grade. [Unpublished Dissertation]. Hofstra University.

Fong Lam, U., Chen, W. W., Zhang, J., & Liang, T. (2015). It feels good to learn where I belong: School belonging, academic emotions, and academic achievement in adolescents. School Psychology International, 36(4), 393–409. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0143034315589649.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F00346543074001059.

Freeman, T. M., Anderman, L. H., & Jensen, J. M. (2007). Sense of belonging in college freshmen at the classroom and campus levels. The Journal of Experimental Education, 75(3), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.75.3.203-220

Friedman, S., & Kuipers, G. (2013). The divisive power of humor: Comedy, taste and symbolic boundaries. Cultural Sociology, 7(2), 179e195. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1749975513477405.

Frymier, B. A., Wanzer, B. M., & Wojtaszczyk, M. A. (2008). Assessing students’ perceptions of inappropriate and appropriate teacher humor. Communication Education, 57(2), 266–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520701687183

Garner, R. L. (2006). Humor in pedagogy: How ha-ha can lead to aha! College Teaching, 54, 177e180. https://doi.org/10.3200/CTCH.54.1.177-180

Glaser, H. F., & Bingham, S. (2009). Students’ perceptions of their connectedness in the community college basic public speaking course. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 9(2), 57–69. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/josotl/article/view/1726

Gong, X., & Bergey, B. W. (2020). The dimensions and functions of students’ achievement emotions in chinese chemistry classrooms. International Journal of Science Education, 42(5), 835–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2020.1734684

Goodboy, A. K., Booth-Butterfield, M., Bolkan, S., & Griffin, D. J. (2015). The role of instructor humor and students’ educational orientations in Student learning, extra effort, participation, and out-of-class communication. Communication Quarterly, 63(1), 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2014.965840

Goodenow, C. (1993a). Classroom belonging among early adolescent students: Relationships to motivation and achievement. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 13(1), 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0272431693013001002.

Goodenow, C. (1993b). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807

Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831

Hall, J. A. (2017). Humor in romantic relationships: A meta-analysis. Personal Relationships, 24(2), 306–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12183

Hillman, S. K. (2011). " Ma Sha Allah!“: Creating community through humor practices in a diverse Arabic language flagship classroom [Unpublished dissertation]. Michigan State University.

Ho, S. K. (2016). Relationships among humour, self-esteem, and social support to burnout in schoolteachers. Social Psychology of Education, 19(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-015-9309-7

Hoad, C., Deed, C., & Lugg, A. (2013). The potential of humor as a trigger for emotional engagement in outdoor education. Journal of Experiential Education, 36(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825913481583

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7CF7R

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hughes, J. N., Im, M. H., & Allee, P. J. (2015). Effect of school belonging trajectories in grades 6–8 on achievement: Gender and ethnic differences. Journal of School Psychology, 53(6), 493–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2015.08.001

Imlawi, J., Gregg, D., & Karimi, J. (2015). Student engagement in course-based social networks: The impact of instructor credibility and use of communication. Computers & Education, 88, 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.04.015

Janosz, M., & Bouthillier, C. (2007). Rapport de validation du Questionnaire sur l’environnement socioéducatif des écoles secondaires (QES-secondaire). https://www.gres.umontreal.ca/download/Rapport_validation_QESsecondaire.pdf

Janosz, M., Georges, P., & Parent, S. (1998). L’environnement socioéducatif à l’école secondaire: un modèle théorique pour guider l’évaluation du milieu. Revue canadienne de psycho-éducation, 27(2), 285–306.

Jiang, F., Lu, S., Jiang, T., & Jia, H. (2020). Does the relation between humor styles and subjective well-being vary across culture and age? A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2213. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02213

Kenny, D. A., & McCoach, D. B. (2003). Effect of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modelling. Structural Equation Modelling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 10(3), 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1003_1

Kibler, A. K., Elreda, M., Hemmler, L., Arbeit, V. L., Beeson, M. R., R., & Johnson, H. E. (2019). Building linguistically integrated classroom communities: The role of teacher practices. American Educational Research Journal, 56(3), 676–715. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0002831218803872.

King, R. B., & Gaerlan, M. J. M. (2014). High self-control predicts more positive emotions, better engagement, and higher achievement in school. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 29(1), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-013-0188-z

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principals and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

Korpershoek, H., Canrinus, E. T., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., & de Boer, H. (2020). The relationships between school belonging and students’ motivational, social emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: A meta-analytic review. Research Papers in Education, 35(6), 641–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1615116

Kosiczky, B., & Mullen, C. A. (2013). Humor in high school and the role of teacher leaders in school public relations. Journal of School Public Relations, 34(1), 6–39. https://doi.org/10.3138/jspr.34.1.6

Kwon, K., Hanrahan, A. R., & Kupzyk, K. A. (2017). Emotional expressivity and emotion regulation: Relation to academic functioning among elementary school children. School Psychology Quarterly, 32(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000166

La Fave, L., Haddad, J., & Maesen, W. A. (1996). Superiority, enhanced self-esteem, and perceived incongruity humour theory. In A. J. Chapman, & H. C. Foot (Eds.), Humor and laughter: Theory, research and applications (pp. 63–91). Transaction Publishers.

Liddle, I., & Carter, G. F. (2015). Emotional and psychological well-being in children: The development and validation of the Stirling Children’s Well-being Scale. Educational Psychology in Practice, 31(2), 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2015.1008409

Liu, H., Yao, M., Li, J., & Li, R. (2021). Multiple mediators in the relationship between perceived teacher autonomy support and student engagement in math and literacy learning. Educational Psychology, 41(2), 116–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1837346

Liu, R. D., Zhen, R., Ding, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, J., Jiang, R., & Xu, L. (2018). Teacher support and math engagement: Roles of academic self-efficacy and positive emotions. Educational Psychology, 38(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2017.1359238

LoVerde, D. (2007). Rules of engagement: Teacher practices that meet psychological needs of students with disabilities in an inclusion science classroom. [Unpublished dissertation]. Hofstra University, Hempstead.

Luo, R., Zhan, Q., & Lyu, C. (2023). Influence of instructor humor on learning engagement in the online learning environment. Social Behavior and Personality, 51(2), e12145. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.12145

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.1.2.130

Marks, H. M. (2000). Student engagement in instructional activity: Patterns in the elementary. middle.

and high school years.American Educational Research Journal, 37,153–184. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312037001153

Martin, R. A. (2010). The psychology of humor: An integrative approach. Elsevier.

Martins, J., Cunha, J., Lopes, S., Moreira, T., & Rosário, P. (2022). School engagement in elementary school: A systematic review of 35 years of research. Educational Psychology Review, 34(2), 793–849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09642-6

Mawhinney, L. (2008). Laugh so you don’t cry: Teachers combating isolation in schools through humour and social support. Ethnography and Education, 3(2), 195–209.

Mbikayi, P., & St-Amand, J. (2017). Gestion de classe, TIC et sentiment d’appartenance à l’école. McGill Journal of Education/Revue des sciences de l’éducation de McGill, 52(3), 783–790. https://doi.org/10.7202/1050914ar

McKeering, P., Hwang, Y. S., & Ng, C. (2021). A study into wellbeing, student engagement and resilience in early-adolescent international school students. Journal of Research in International Education, 20(1), 69–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/14752409211006650

Mendiburo-Seguel, A., Páez, D., & Martínez‐Sánchez, F. (2015). Humor styles and personality: A meta‐analysis of the relation between humor styles and the big five personality traits. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56(3), 335–340.

Mesmer-Magnus, J., Glew, D. J., & Viswesvaran, C. (2012). A meta-analysis of positive humor in the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(2), 155–190.

Newmann, F. M., Wehlage, G. G., & Lamborn, S. D. (1992). The significance and sources of student engagement. In F. M. Newmann (Ed.), Student engagement and achievement in american secondary schools (pp. 11–39). Teachers College Press.

Nguyen, T. D., Cannata, M., & Miller, J. (2018). Understanding student behavioral engagement: Importance of student interaction with peers and teachers. The Journal of Educational Research, 111(2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2016.1220359

Nwokah, E. E., Burnette, S. E., & Graves, K. N. (2013). Joke telling, humor creation, and humor recall in children with and without hearing loss. Humor, 26(1), 69–96. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2013-0005

Özdemir, E. (2017). Humor in elementary science: Development and evaluation of comic strips about sound. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 9(4), 837–850.

Ozer, E. J., Wolf, J. P., & Kong, C. (2008). Sources of perceived school connection among ethnically-diverse urban adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23(4), 438–470. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0743558408316725.

Pekrun, R. (2000). A social cognitive, control-value theory of achievement emotions. In J. Heckhausen (Ed.), Advances in psychology. Motivational psychology of human development: Developing motivation and motivating development (pp. 143–163). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4115(00)80010-2

Pekrun, R., Elliot, A. J., & Maier, M. A. (2006). Achievement goals and discrete achievement emotions: A theoretical model and prospective test. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(3), 583–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.3.583

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of quantitative and qualitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4

Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2012). Academic emotions and student engagement. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 259–282). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_12

Perry, J. L., Nicholls, A. R., Clough, P. J., & Crust, L. (2015). Assessing model fit: Caveats and recommendations for confirmatory factor analysis and exploratory structural equation modeling. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 19(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1091367x.2014.952370

Perreault, C. (1989). The Santé-Québec survey and mental health of Québecers: Conceptual framework and methodology. Revue Santé mentale au Québec, 14(1), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.7202/031494ar

Rambe, A. S., & Harahap, K. S. (2023). Superior classroom management strategies to improve learning quality. Jurnal Pendidikan dan Konseling (JPDK), 5(1), 629–635. https://doi.org/10.31004/jpdk.v5i1.10999

Reschly, A. L., Huebner, E. S., Appleton, J. J., & Antaramian, S. (2008). Engagement as flourishing: The contribution of positive emotions and coping to adolescents’ engagement at school and with learning. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 419–431. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20306

Sahayu, W., Triyono, S., Kurniawan, E., Baginda, P., & Tema, N. H. G. (2022). Children’s humor development: A case of indonesian children. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 11(3), 729–736. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v11i3.43707

Sari, M. (2013). Sense of school belonging among high school students. Anadolu University Journal of Social Sciences, 13(1), 147–160.

Seaman, L. G. (2017). Exploring student engagement and middle-school students’ perceptions of humor used as a teaching tool [Unpublished Dissertation]. Northcentral University.

Sidelinger, R. J., Frisby, B. N., McMullen, A. L., & Heisler, J. (2012). Developing student-to-student connectedness: An examination of instructors’ humor, nonverbal immediacy, and self-disclosure in public speaking courses. Basic Communication Course Annual, 24(1), 8. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/bcca/vol24/iss1/8

Smith, J., Moreau, D., Paquin, St-Amand, J., & Chouinard, R. (2020). The evolution of motivation to learn in the context of the transition to secondary school: Developmental trajectories and relational determinants. The International Journal of Pedagogy and Curriculum, 27(2), 17–37.

Snyder, D. W. (1998). Classroom management for student teachers. Music Educators Journal, 84(4), 37–40.

St-Amand, J. (2016). Le sentiment d’appartenance à l’école: un regard conceptuel, psychométrique et théorique [School belonging: A conceptual, psychometric and theoretical perspective] [Unpublished dissertation]. Université de Montréal.

St-Amand, J. (2018). An examination of teachers’ classroom management: Do gender stereotypes matter in student–teacher relations? The Online Journal of New Horizons in Education, 8(3), 1–9.

St-Amand, J., Boily, R., Bowen, F., Smith, J., Janosz, M., & Verner-Filion, J. (2020a). The development of the french version of the psychological sense of School Membership (PSSM) questionnaire: An analysis of its structure, properties and potential for research with at-risk students. Interdisciplinary Education and Psychology, 2(3), 3. https://doi.org/10.31532/InterdiscipEducPsychol.2.3.003

St-Amand, J., Bowen, F., Bulut, O., Cormier, D., Janosz, M., & Girard, S. (2020b). Le sentiment d’appartenance à l’école: Validation d’un modèle théorique prédisant l’engagement et le rendement scolaire en mathématiques d’élèves du secondaire [School belonging: Validation of a theoretical model that predicts school engagement and academic achievement in mathematics]. Formation et Profession, 28(2), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.18162/fp.2020.530

St-Amand, J., Bowen, F., & Lin, T. (2017c). Le sentiment d’appartenance à l’école: Une analyse conceptuelle [School belonging: A conceptual analysis]. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue Canadienne de l’éducation, 40(1), 1–32.

St-Amand, J., Girard, S., Hiroux, M. H., & Smith, J. (2017a). Participation in sports-related extracurricular activities: A strategy that enhances school engagement. McGill Journal of Education / Revue des sciences de l’éducation de McGill, 52(1), 197–206. https://doi.org/10.7202/1040811ar

St-Amand, J., Girard, S., & Smith, J. (2017b). Sense of belonging at school: Defining attributes, determinants, and sustaining strategies. IAFOR Journal of Education, 5(2), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.22492/ije.5.2.05

St-Amand, J., Smith, J., Béland, S., & Moreau, D. (2021a). Understanding teacher’s humor and its attributes in Classroom management: A conceptual study. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 21(2), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.12738/jestp.2021.2.008

St-Amand, J., Smith, J., & Rasmy, A. (2021b). Development and validation of a model predicting students’ sense of school belonging and engagement as a function of school climate. International Journal of Learning Teaching and Educational Research, 20(12), 64–84. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.20.12.5

Stuart, W. D., & Rosenfeld, L. B. (1994). Student perceptions of teacher humor and classroom climate. Communication Research Reports, 11(1), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824099409359944

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson.

Tanay, M. A. L., Roberts, J., & Ream, E. (2013). Humor in adult cancer care: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(9), 2131–2140. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12059

Tsukawaki, R., & Imura, T. (2020). Preliminary verification of instructional humor processing theory: Mediators between instructor humor and student learning. Psychological Reports, 123(6), 2538–2550. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0033294119868799

Walter, N., Cody, M. J., Xu, L. Z., & Murphy, S. T. (2018). A priest, a rabbi, and a minister walk into a bar: A meta-analysis of humor effects on persuasion. Human Communication Research, 44(4), 343–373. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqy005

Wanzer, M. B., Frymier, A. B., & Irwin, J. (2010). An explanation of the relationship between instructor humor and student learning: Instructional humor processing theory. Communication Education, 59(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520903367238

Wanzer, M. B., Frymier, A. B., Wojtaszczyk, A. M., & Smith, T. (2006). Appropriate and inappropriate uses of humor by teachers. Communication Education, 55(2), 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520600566132

Wehlage, G. G., Rutter, R. A., Smith, A. G., Lesko, N., & Fernandez, R. R. (1989). Reducing the risk: Schools as communities of support. Falmer Press.

Zillmann, D., & Cantor, J. R. (1996). A disposition theory of humour and mirth. In A. J. Chapman, & H. C. Foot (Eds.), Humor and laughter: Theory, research and applications (pp. 93–115). Transaction Publishers. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203789469

Ziyaeemehr, Z. (2011). Use and non-use of humor in academic ESL classrooms. English Language Teaching, 4(3), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n3p111

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. This work was supported by The Fonds de Recherche du Québec Société et Culture. The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

St-Amand, J., Smith, J. & Goulet, M. Is teacher humor an asset in classroom management? Examining its association with students’ well-being, sense of school belonging, and engagement. Curr Psychol 43, 2499–2514 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04481-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04481-9