Abstract

Relationships between parents and their descendants are necessary for healthy socio-emotional development. For a better understanding of these relationships, past studies found that personality traits significantly impact parenting constructs, such as attachment patterns, parental care, and relationship satisfaction, suggesting that the psychological aspects of parents can affect their descendants. In our research (N = 250), we asked participants to rate how they perceive their parents regarding their aversive personality traits (i.e., Dark Triad), parenting style characteristics, relationship satisfaction, and their own well-being and self-esteem. We then developed two mediational models (SEM), one for mothers and one for fathers. In these models, we assessed how the Dark Triad impacted mental health and self-esteem, mediated by authoritarian parenting style and relationship satisfaction. The models presented a good fit (e.g., CFI > 0.90). Psychopathic traits positively influenced an authoritarian parenting style for both parents, leading to worse relationship satisfaction and affecting their descendants’ mental health and self-esteem. Furthermore, we also observed the indirect effects of parental psychopathy on our outcomes, which were higher for mothers than fathers. Overall, our study provides the first assessment of how parents’ higher levels of dark traits can influence their descendants’ mental health and self-esteem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rolf Mengele, the only son of Josef Mengele, also known as the Angel of Death, visited his father in a hideout in the suburbs of Sao Paulo years after the end of the II World War (Ware, 2020). Josef Mengele was one of the main ones responsible for Auschwitz. He conducted a series of deadly experiments, especially with twins, and was seen as a person who completely lacked remorse (Lifton, 1985). In his visit, Rolf intended to dialogue with his long-disappeared father about his behavioral motivations during the war. Rolf could not get the answers he was hoping for, but instead, he became more aware of his father’s dark personality, mood swings, and depression. After their farewell, they never spoke again (Ware, 2020). Rolf is only one of the many children of Nazism, and even though he did not have the presence of his father when growing up, he had to live with his image and all the atrocities he caused to humankind.

Josef’s story is just one of many that can exemplify a relationship between parents who highly present aversive personality traits. Studies assessing the link between these traits and their impact on parenthood have gained attention in the past years, especially with the development of proper measures that allow the understanding of these traits in non-clinical populations (Jonason & Webster, 2010). More specifically, researchers assessed how specific dark traits (e.g., sadism, psychopathy) could be linked to several parenting-related aspects: attachment patterns and parental care (Jonason et al., 2014), preference for partner parenting style (Lyons et al., 2020), quality of the relationship between parent and child (Tajmirriyahi et al., 2021), and even judicial manipulation after parents splitting up (Clemente et al., 2020). In the present research, we focused on whether well-being and self-esteem are impacted by how people perceive their parents regarding these aversive personality traits.

The dark triad and parenthood

The Dark Triad originated from the literature on aversive personality traits and reunites three dimensions with a more considerable empirical background (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Machiavellianism describes individuals that tend to present manipulative and callous behaviors, focusing on benefits for the self (Jones & Paulhus, 2009). Psychopathy characterizes individuals who engage in antisocial behaviors, are impulsive and lack remorse or empathy towards others (Jones & Paulhus, 2011; Patrick et al., 2009). Finally, narcissism defines individuals with an inflated self-concept, thinking about themselves tremendously and superiorly (Miller et al., 2017). Nowithisdanting, despite their unique characteristics, these negative personality traits have many intrinsic and highly related features, with research suggesting an overlap between them (Paulhus & Williams, 2002).

The popularization of the term Dark Triad and measures to assess the construct in non-clinical populations (e.g., Dark Triad Dirty Dozen; Jonason & Webster, 2010) helped boost the development of empirical studies using these constructs within the past decades across different samples. Interpersonal relationships are one of the aspects severely impacted by aversive personality traits. For instance, individuals with higher Machiavellianism and psychopathy tend to engage in psychological abuse in their intimate relationships (Carton & Egan, 2017). Further, company leaders who present high levels of dark traits harm the careers and well-being of their employees (Volmer et al., 2016), even leading to depression (Tokarev et al., 2017).

In addition to impacting intimate and work relationships, researchers are also interested in looking at the effect of these traits on parental relationships. Jonason et al. (2014) found that different aspects of the Triad (e.g., grandiose, exhibitionism, primary psychopathy) are linked to poorer quality of parental care in mothers and fathers. More specifically, the quality of maternal care was negatively correlated to the three dark traits, with a higher association with narcissism (r = − .54, p < .01). On the other hand, paternal care, also linked to all three dark traits, had a higher association with Machiavellianism (r = − .30, p < .01). Such differences suggest that the quality of parental care might be impacted by different traits, depending on the parent. Furthermore, Tajmirriyahi et al. (2021) reported that individuals with a higher Machiavellianism tended to present worse relationship quality with their parents. Despite these insightful and essential findings, it is still unknown to what extent having parents who present dark personality traits can impact the well-being and self-esteem of their descendants.

Parenting styles

According to Bowlby’s attachment theory, exploring such relationships is essential, as early experiences between parents and children are fundamental for the subsequent socioemotional development of their descendants (Delgado et al., 2022). And different parental styles might impact children differently. For instance, descendants with responsive parents receive care, protection, and affection. They tend to have higher levels of well-being, whereas those deprived of such care present insecure attachments and have more anxiety, depression, and lower self-esteem (Clery et al., 2021; Lee & Hankin, 2009). The quality of parental care is also known for being associated with attachment patterns, differing between the parents. While maternal care is linked to secure, avoidant and fearful attachments, paternal care is associated with an avoidant type (Jonason et al., 2014). Finally, in a systematic review (from 1990 to 2020) assessing parental differences regarding their styles, mothers presented significantly higher authoritative styles, whereas fathers mainly were authoritarians (Yaffe, 2020).

Considering that people’s personality traits predict the parenting style they adopt, it is essential to consider such individual differences in the study of parenting and its effects on their descendants (Desjardins et al., 2008). In this direction, Fan et al. (2020) recently assessed how personality traits could impact subjective well-being in a study considering both parents and children. However, their study focused on two core traits (extroversion and neuroticism). Importantly, they found that higher levels of extroversion in parents significantly predicted higher subjective well-being in children. In contrast, higher levels of neuroticism were linked with lower levels of subjective well-being. Therefore, it is essential to understand how people perceive their parents regarding their dark personality traits and assess how these can impact their lives.

The present research

In the present research, we aimed to assess whether mental health and self-esteem are impacted by how individuals perceive the dark traits in their parents. In other words, to assess the Dark Triad, we asked each participant to rate their parents regarding their perceived aversive personality traits. This approach aligns with previous studies, that showed that the use of other-report for the Dark Triad is highly similar to the actual self-reported traits (Kardum et al., 2022). We also considered parental styles (affect and control) and relationship satisfaction, variables that are important to this family relationship. To achieve our goal, we first assessed the correlations between the perceived Dark Triad, parental styles, relationship satisfaction, mental health, and self-esteem. Then, we developed two mediational models, one for each parent, to assess the mechanisms underlying their relations and how the variables impact each other. More specifically, how the perceived personality traits impact parental style, which affects relationship satisfaction, finally directly explains well-being and self-esteem.

Even though it is not the focus of this study, it is relevant to highlight beforehand the impact gender might exert on the variables that we are using. For instance, research has shown that men tend to present higher levels of dark traits (e.g., Jonason et al., 2009) and lower levels of agreeableness and neuroticism (e.g., Chapman et al., 2007). Thus, we could expect men to present a more ‘cold’ or ‘dark’ perception of their parents when answering the other-report questionnaire. Still, as our research focuses on the general perception of dark traits in parents and how this could impact their children’s mental health and self-esteem, we did not control for gender impact.

Method

Procedure and participants

We collected all data online, with the researchers advertising the link on social networks such as Facebook, Instagram, and Whatsapp. Anyone over 18 years old and from Brazil was welcome to click the link and freely complete the questionnaire, with no further screenings. The research link provided information regarding the purposes of the study, its anonymous character, and the voluntary nature of participants’ participation. In total, 250 individuals (M = 24.6; SD = 9.96; Women = 166; Men = 84) completed the questionnaire. Most of them self-declared to be single (72.8%), of middle social class (45.2%), and with an incomplete higher education (50%). The full description of the sample is available as Online Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table 1).

Material

We used the Brazilian version (Gouveia et al., 2016) of the Dark Triad Dirty Dozen (Jonason & Webster, 2010). Participants had to answer two versions of the scale, one having the mother as a reference and the other as the father. We adapted the 12 items from self-report to other-report for the present study. That is, using a five-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 5 = Strongly Agree), participants should indicate how much each of the items (e.g., “He tends to manipulate others to get his way”, Machiavellianism; “She tends to be unconcerned with the morality of my actions”, psychopathy; “He tends to seek prestige or status.”, narcissism) are characteristic of their parents. We found good levels of reliability for both adaptions of the measure (Kline, 2013): Machiavellianism (Cronbach’s alpha, α = 0.82 for mothers, α = 0.91 for fathers), psychopathy (α = 0.79 for mothers, α = 0.80 for fathers), and narcissism (α = 0.84 for mothers, α = 0.87 for fathers).

Further, we used a shorter 8-item version of the Parental Perception Scale (Pasquali et al., 2012), for both mothers and fathers. For this study, we selected the items with higher factorial loadings for the affect (e.g. “My mother comforts me when I am sad”) and control (e.g., “My father punishes me when I do not obey”) factors, four per factor. Participants should indicate how much each item applies to their parents, using a seven-point scale (1 = Not applicable; 7 = Totally applicable). Both the version for fathers (α = 0.90 for affect, α = 0.80 for control) and for mothers (α = 0.90 for affect, α = 0.91 for control) presented good reliability levels (Kline, 2013).

We also used the Brazilian version (Damásio et al., 2014) of the Five-Item Mental Health Index (McHorney & Ware, 1995). This abbreviated measure assesses symptoms of depression (e.g., “Have you felt downhearted and blue?”) and anxiety (e.g., “Have you been a very nervous pearson?”) in clinical and non-clinical samples. Participants have to indicate the frequency (1 = Never; 5 = All the time) of these symptoms in the last month. The measure presented good internal consistency (α = 0.84).

Participants also answered the Brief Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Monteiro et al., 2021). Participants answer the five items (e.g. “On the hole, I am satisfied with myself”) of this one-factor measure using an agreement seven-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 7 = Strongly Agree). The measure presented good internal consistency (α = 0.89).

Finally, participants answered single items about their relationship satisfaction with their parents, one per parent, using a five-point scale ( 1 = Totally Dissatisfied; 5 = Totally Satisfied).

Data analysis

We analyzed data using SPSS and AMOS. In SPSS, we performed descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and Pearson’s correlation analysis. In AMOS, we performed two Structural Equation Modeling (Maximum Likelihood estimator). For model fit, we used the following indicators (Hair et al., 2022; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019): χ²/df (should be between 2 and 5), Comparative Fit Index and Tucker-Lewis Index (both over 0.90), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (lower than 0.08). In addition, we used bootstrapping with 5,000 resamplings to calculate the indirect effects in the model.

Results

Initially, we assessed the correlations between all studied variables and mental health and self-esteem (Table 1). Specifically, individuals who reported having mothers with higher levels of Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism also reported lower mental health and self-esteem. Also, perceiving the mother as affectionate and maintaining a good relationship with her was positively related to mental health and self-esteem, whereas perceiving her as controlling was negatively linked with self-esteem. We found similar results for fathers, with higher levels of perceived psychopathy and narcissism linked to lower mental health and self-esteem. Affectuous fathers and maintaining a good relationship were positively correlated with mental health and self-esteem.

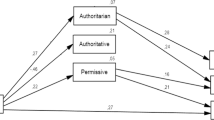

After, we tested two double mediation models, one for each parent, using Structural Equation Modeling. We created the variable authoritarian parenting style (high control and low affect; Pasquali et al., 2012) to include in these models, reflecting parents who score high in control and present little affection (we created a total score with the inverted affection items). In both models, we used the perceived dark personality traits as predictors of this authoritarian parenting style, which would explain relationship satisfaction. This is the proximal variable that would predict mental health and self-esteem. The models can be seen in Fig. 1.

Two pairs of items were correlated (two narcissism items reflecting attention-seeking and two inverted items from the Brief Self-Esteem Scale) in both models. For mothers, the model presented an acceptable fit to the data (χ²/df = 2.18; CFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.069). Among the dark traits, mothers with psychopathic traits presented an authoritarian parenting style (λ = 0.85; p < .01), which predicted relationship satisfaction (λ = − 0.80; p < .01), which, in turn, directly influenced their descendants’ mental health (λ = 0.40; p < .01) and self-esteem (λ = 0.40; p < .01). Furthermore, there were indirect effects of the mother’s psychopathic traits on the relationship satisfaction (λ= − 0.68, p < .01), in addition to these traits indirectly influencing their descendants’ mental health (λ= − 0.27; p <. 01) and self-esteem (λ= − 0.27; p < .01) via parenting style and relationship satisfaction with the mother.

The model tested also presented an acceptable fit for fathers: (χ²/df = 2.35; CFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.074). Among the dark traits, fathers with psychopathic traits (λ = 0.68; p < .01) had more authoritarian parenting practices, and such practices resulted in worse relationship satisfaction (λ=-0.95; p < .01 ), which in turn predicted their descendants’ mental health (λ = 0.28; p < .01) and self-esteem (λ = 0.38; p < .01). Finally, there were indirect effects of fathers’ psychopathic traits on the relationship satisfaction (λ=-0.64; p < .01), in addition to such traits, indirectly influencing their descendants’ mental health (λ=-0.18; p < .01) and self-esteem (λ=-0.25; p < .01) through parenting style and relationship satisfaction with the father.

Discussion

Past studies showed the link between dark personality traits and parenting constructs, such as attachment patterns and parental care (Jonason et al., 2014) and the relationship satisfaction between parent and child (Tajmirriyahi et al., 2021). In the present research, we assessed whether individuals’ mental health and self-esteem are impacted by their perception of their parents as possessing aversive traits. More specifically, we asked individuals to rate how they perceive their parents regarding their dark traits (i.e., Machiavellianism, psychopathy, narcissism). We then analyzed whether these perceived traits impact parental style, relationship satisfaction, and their sons’ and daughters’ mental health and self-esteem.

First, we assessed the correlations between mental health, self-esteem, the perceived Dark Triad, parental styles (affect and control), and relationship satisfaction, separating mothers from fathers. We tested separate models because they involve the perception of different people (father and mother), who have independent characteristics. Furthermore, men and women differ in personality traits (Jonason et al., 2009) and parenting behaviors (Möller et al., 2013). According to these authors, fathers and mothers have a specific role in transmitting intergenerational anxiety. For example, very affectionate fathers (in the article, referred to as paternal warmth) promote greater well-being, while affectionate mothers (i.e., maternal warmth) cause the opposite. Therefore, we decided to test these effects separately.

Most of these associations were significant. As expected, perceiving parents as less Machiavelli, psychopath, or narcissistic is linked to higher mental health and self-esteem. Curiously, perceived psychopathy is the variable with higher correlations with mental health and self-esteem for both mothers and fathers. The trait is known as the most malevolent of the Dark Triad, describing individuals who are high in dominance and low on nurturance (Rauthmann, 2012), characteristics that, in a parenting environment, would reflect authoritarian parenting styles (Hoeve et al., 2011). Despite not comparing with the other two dimensions of the Dark Triad, previous studies have highlighted this association between psychopathy and well-being. For instance, corporate psychopathy in employers, reported by their own employees, results in higher psychological distress and lower job satisfaction (Mathieu et al., 2014). Furthermore, perceived psychopathic traits significantly explain ill-being and well-being variables, such as depression, negative and positive affects, life satisfaction, and happiness (Love & Holder, 2014). Therefore, being the most malevolent dark trait and its known impact on well-being helps to explain our findings.

Further, we developed two mediational models, one for each parent. Results were quite similar for both mothers and fathers. As for the correlations, perceived psychopathy was the only significant aversive trait in the model. It predicted positively and significantly an authoritarian parental style. In other words, the higher the levels of perceived psychopathy, the higher the adoption of an authoritarian profile while parenting. Embracing this parenting style also led to lower relationship satisfaction between parents and the respondents. Finally, and as expected, a greater relationship satisfaction positively influenced mental health and self-esteem. Also, perceived psychopathic traits in parents indirectly, significantly, and negatively impact relationship satisfaction, mental health, and self-esteem. Such findings again highlight the impact that the perception of this malevolent trait can have on others (e.g., Mathieu et al., 2014). These results align with aspects indicated by Bowlby’s attachment theory, suggesting that relationships between parents and children are fundamental for positive socioemotional development (Delgado et al., 2022). Individuals with higher levels of dark traits are less emphatic, unapologetic, manipulative, and individualistic (Paulhus & Williams, 2002), and their traits negatively impact a range of interpersonal relationships (e.g., Carton & Egan, 2017; Volmer et al., 2016). Therefore, these aversive traits also impact the relationship between parents and their offspring. Parents with psychopathic characteristics tend to adopt a more authoritarian style, influencing their descendents’ mental health, in line with previous studies (Kim et al., 2021).

Curiously, the indirect impacts of perceived psychopathic traits on relationship satisfaction, mental health, and self-esteem were higher for mothers than fathers. One possible explanation for such findings is that mothers tend to have a stronger attachment to their descendants than fathers (Hoeve et al., 2012). Therefore, perceiving the mother as non-caring and possessing aversive personality traits could help break the social role that mothers are caring and present. In contrast, fathers are less involved in parenting (Ahnert & Schoppe-Sullivan, 2020). Therefore, it is crucial to consider personality traits in the study of parent-child relationships (Desjardins et al., 2008), including dark traits, as they play a key role in explaining problems in interpersonal relationships and adverse outcomes.

Limitations, future studies and conclusion

Despite our study’s relevant findings, it is important to highlight potential limitations. First, the use of self and other-report questionnaires to assess the constructs. Despite the reliability levels of these questionnaires, these types of questionnaires are known for being susceptible to social desirability, i.e., participants providing biased answers and hiding their true beliefs. Thus, we recommend future studies to control for this effect. Second, we relied on participants’ perceptions and memory to assess their parents’ Dark Triad. The mean age in our study is of a young adult (M = 24.6; SD = 9.96), but still, this time difference between their formative years and young adulthood could have led them to produce distorted perceptions of their parents. Future studies could include children and longitudinally assess the impact of their parents’ dark traits and the development of their well-being through the years. Third, we did not control whether the participants grew up with their parents living together or whether they were separated. It is known that children are largely exposed to parental alienation behaviors after a separation (Baker & Chambers, 2011), which might influence how they perceive their parents. Future studies could control for such a potential cofounder. Finally, our study presented 166 women (66.4%) and 84 men (33.6%), an uneven distribution of gender. Future studies could benefit from a more gender-equitable sample, allowing us to test the moderating role of this variable. Such a sample could also benefit the study of gender differences, helping to assess whether higher levels of specific personality traits (e.g., agreeableness) could lead to a more positive perception of the parents.

Our study provides the first assessment of how parents’ higher levels of dark traits can influence their descendants’ mental health and self-esteem. Due to the stable character of the personality, we are confident that parents with dark personality traits will negatively affect their children from an early age, with the effects accumulating over time. More specifically, we identified that psychopathy has a higher impact on these relationships and that this impact is higher when psychopathic traits are present in mothers. We are confident that our findings could benefit researchers and family clinicians, providing a different overview of how aversive characteristics can influence well-being.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ahnert, L., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2020). Fathers from an attachment perspective. Attachment & Human Development, 22(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2019.1589054

Baker, A. J. L., & Chambers, J. (2011). Adult Recall of Childhood exposure to parental conflict: unpacking the Black Box of parental alienation. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 52(1), 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2011.534396

Carton, H., & Egan, V. (2017). The dark triad and intimate partner violence. Personality and Individual Differences, 105, 84–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.09.040

Chapman, B. P., Duberstein, P. R., Sörensen, S., & Lyness, J. M. (2007). Gender differences in five factor model personality traits in an Elderly Cohort: extension of robust and surprising findings to an older generation. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(06), 1594–1603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.028

Clemente, M., Padilla-Racero, D., & Espinosa, P. (2020). The Dark Triad and the detection of parental judicial manipulators. Development of a judicial manipulation scale. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082843. Article 8.

Clery, P., Rowe, A., Munafò, M., & Mahedy, L. (2021). Is attachment style in early childhood associated with mental health difficulties in late adolescence? BJPsych Open, 7(S1), S15–S15. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.98

Damásio, B. F., Borsa, J. C., & Koller, S. H. (2014). Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the brazilian version of the five-item Mental Health Index (MHI-5). Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 27, 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-7153.201427213

Delgado, E., Serna, C., Martínez, I., & Cruise, E. (2022). Parental attachment and peer Relationships in Adolescence: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031064

Desjardins, J., Zelenski, J. M., & Coplan, R. J. (2008). An investigation of maternal personality, parenting styles, and subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(3), 587–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.020

Fan, H., Li, D., Zhou, W., Jiao, L., Liu, S., & Zhang, L. (2020). Parents’ personality traits and children’s subjective well-being: a chain mediating model. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01078-4

Gouveia, V. V., Monteiro, R. P., Gouveia, R. S. V., Athayde, R. A. A., & Cavalcanti, T. M. (2016). Avaliando O Lado Sombrio Da Personalidade: Evidências Psicométricas do Dark Triad dirty dozen. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 50(3), 420–432.

Hair, J. F. Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2022). Multivariate Data Analysis (8th edition). Cengage Learning.

Hoeve, M., Dubas, J. S., Gerris, J. R. M., van der Laan, P. H., & Smeenk, W. (2011). Maternal and paternal parenting styles: unique and combined links to adolescent and early adult delinquency. Journal of Adolescence, 34(5), 813–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.02.004

Hoeve, M., Stams, G. J. J. M., van der Put, C. E., Dubas, J. S., van der Laan, P. H., & Gerris, J. R. M. (2012). A Meta-analysis of attachment to parents and delinquency. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(5), 771–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9608-1

Jonason, P. K., Li, N. P., Webster, G. D., & Schmitt, D. P. (2009). The dark triad: facilitating a short-term mating strategy in men. European Journal of Personality, 23, 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.698

Jonason, P. K., Lyons, M., & Bethell, E. (2014). The making of Darth Vader: parent–child care and the Dark Triad. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 30–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.10.006

Jonason, P. K., & Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen: a concise measure of the dark triad. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 420–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019265

Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2009). Machiavellianism. In M. R. Leary, & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 102–120). Guilford.

Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2011). The role of impulsivity in the Dark Triad of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(5), 679–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.04.011

Kardum, I., Hudek-Knezevic, J., & Mehic, N. (2022). Similarity indices of the Dark Triad traits based on self and partner-reports: evidence from variable-centered and couple-centered approaches. Personality and Individual Differences, 193, 111626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111626

Kim, S. H., Baek, M., & Park, S. (2021). Association of parent–child experiences with Insecure attachment in Adulthood: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 13(1), 58–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12402

Kline, P. (2013). Handbook of psychological testing. Routledge.

Lee, A., & Hankin, B. L. (2009). Insecure attachment, dysfunctional attitudes, and low self-esteem Predicting prospective symptoms of depression and anxiety during adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38(2), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802698396

Lifton, R. J. (1985, July 21). What made this man? Mengele. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/07/21/magazine/what-made-this-man-mengele.html

Love, A. B., & Holder, M. D. (2014). Psychopathy and subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 66, 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.033

Lyons, M., Brewer, G., & Carter, G. L. (2020). Dark Triad traits and preference for partner parenting styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 152, 109578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109578

Mathieu, C., Neumann, C. S., Hare, R. D., & Babiak, P. (2014). A dark side of leadership: corporate psychopathy and its influence on employee well-being and job satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 59, 83–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.11.010

McHorney, C. A., & Ware, J. E. (1995). Construction and validation of an alternate form general mental health scale for the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey. Medical Care, 33(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199501000-00002

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Hyatt, C. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2017). Controversies in Narcissism. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13(1), 291–315. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045244

Möller, E. L., Majdandžić, M., de Vente, W., & Bögels, S. M. (2013). The evolutionary basis of sex differences in parenting and its relationship with child anxiety in Western Societies. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 4(2), 88–117. https://doi.org/10.5127/jep.026912

Monteiro, R. P., Coelho, G. L., de Hanel, H., de Medeiros, P. H. P., E. D., & da Silva, P. D. G. (2021). The efficient Assessment of Self-Esteem: proposing the brief Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Applied Research in Quality of Life. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-09936-4

Pasquali, L., Gouveia, V. V., Santos, W. S., dos, Fonsêca, P. N., de da, Andrade, J. M., & de Lima, T. J. S. (2012). Questionário de percepção dos pais: Evidências de uma medida de estilos parentais. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 22, 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-863X2012000200002

Patrick, C. J., Fowles, D. C., & Krueger, R. F. (2009). Triarchic conceptualization of psychopathy: Developmental origins of disinhibition, boldness, and meanness. Development and Psychopathology, 21(3), 913–938. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409000492

Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

Rauthmann, J. F. (2012). The Dark Triad and interpersonal perception: similarities and differences in the social consequences of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(4), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611427608

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using Multivariate Statistics (7th edition). Pearson.

Tajmirriyahi, M., Doerfler, S. M., Najafi, M., Hamidizadeh, K., & Ickes, W. (2021). Dark Triad traits, recalled and current quality of the parent-child relationship: a non-western replication and extension. Personality and Individual Differences, 180, 110949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110949

Tokarev, A., Phillips, A. R., Hughes, D. J., & Irwing, P. (2017). Leader dark traits, workplace bullying, and employee depression: exploring mediation and the role of the dark core. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(7), 911–920. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000299

Volmer, J., Koch, I. K., & Göritz, A. S. (2016). The bright and dark sides of leaders’ dark triad traits: Effects on subordinates’ career success and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 413–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.046

Ware, J. (2020). When Rolf questioned his father, the ‘doctor’ of Auschwitz. https://www.thejc.com/news/features/when-rolf-mengele-questioned-his-father-the-doctor-of-auschwitz-1.497344

Yaffe, Y. (2020). Systematic review of the differences between mothers and fathers in parenting styles and practices. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01014-6

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Coelho, G., Monteiro, R.P., Lannes, A. et al. Are my parents psychopaths? How Mental health and self-esteem is impacted by perceived dark traits in parents. Curr Psychol 43, 2307–2314 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04457-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04457-9