Abstract

This study addresses how goal orientation relates to different job search strategies to increase the chance of finding employment and quality jobs. We integrate the goal orientation theory with self-control to examine how the orientation of goals (i.e., performance-prove goal orientation (PPGO), performance-avoid goal orientation (PAGO) and learning goal orientation (LGO)) are associated with job search strategies (i.e., Focused Job Search Strategy- FJSS, Exploratory Job Search Strategy-EJSS, and Haphazard Job Search Strategy-HJSS) and how self-control moderates the process. In a three-wave study (nT1= 859; nT2 = 720; nT3 = 418), the hypotheses were tested using unemployed job seekers in Ghana. The results from the structural equation model show that learning goal oriented job seekers were inclined to search more focused and exploratory but engaged in less haphazard search. While PPGO facilitated EJSS, job seekers with PAGO searched more haphazardly but their search behaviour was less focused and exploratory. In addition, EJSS contributed to attending more job interviews, but HJSS decreased the chance of obtaining job interviews. Also, the interviews attended were associated with job offered, which in turn led to obtaining employment. Both FJSS and EJSS were related to employment quality but HJSS decreased employment quality. Interestingly, individual differences in self-control were found to moderate the relation between goal orientation and job search strategy. The use of EJSS was found to be more beneficial in difficult labour markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Labour markets across the globe have been changing considerably in recent years and finding suitable employment has become an urgent and challenging task for job seekers in many countries (Wanberg, 2012). The unemployment situation is increasingly dire due to the emergence of the novel coronavirus 2019 (McFarland et al., 2020). As a result, more people are attracted to increase their job search behaviour to end their unemployment situation (van Hooft et al., 2021). A successful job search results from a goal-directed job search activity, which guarantees post-employment quality (Hoye & Saks, 2008). Thus, scholars have recommended job seekers to consider the quality (i.e., Focused Job Search Strategy -FJSS, Exploratory Job search Strategy - EJSS, and Haphazard Job Search Strategy - HJSS: cf.: Crossley & Highhouse, 2005; Stevens & Beach, 1996) at which they search for jobs (van Hooft et al., 2021). Many research outcomes have conceptualised the search for jobs as a self-regulatory behaviour (see Kanfer et al., 2001), hence job seekers need the motivation to sustain high-quality and goal-oriented job search strategies (Okay-Somerville & Scholarios, 2022).

Research shows that goal orientation is a critical motivational force, which is linked to people’s interpretations and understanding regarding how events unfold during goal pursuits (Dineen et al., 2018). Goal orientation has been associated with job search intentions in many developed countries including the United State (e.g., Dineen et al., 2018), Australia (e.g., Creed, King, Hood, & McKenzie, 2009), and Holland (van Hooft & Noordzij, 2009). Nonetheless, there are limitations of previous research, which require further studies in less developed countries to understand the job search process to assist job seekers’ career development. For instance, we know that goal orientation predicts job search intensity (e.g., Wang & Yan, 2018), we do not know how goal orientation explains the three types of job-seeking strategies. Thus, there is still much to explore about how individual differences in goal orientation affect these job search strategies, and subsequent employment outcomes.

Additionally, self-regulation strategies are critical to volitional processes (DeShon & Gillespie, 2005) and it is particularly relevant for researchers to explore the interaction of goal-setting factors in navigating the employment process (Vandewalle et al., 2019). A critical and relevant self-regulatory construct that has been overlooked in this area of research is self-control. One related study, which linked self-control to job-hunting activities focused on the intensity of job search (Baay et al., 2014), but we know of no empirical study, which has explored the moderating role of self-control in the goal orientation—job search strategy link. Self-control provides individuals with capabilities to exert control over the self; in thoughts, feelings, or behaviour, to help them prioritise long-term over short-term goal pursuits (Holding et al., 2019). Thus, we do not believe that the goal orientation—job search strategy link will be unaffected by self-control. Consequently, we incorporate self-control as a moderator to help highlight this process.

Furthermore, majority of researches conducted on the hunt for jobs and reemployment concentrate in developed countries (see Koen et al., 2010, 2016; van Hooft et al., 2021; Van Hoye et al., 2009), bringing to attention regarding the reliability of the measures used in assessing job search strategies in developing countries (Priyadarshini et al., 2021). Due to fewer employment opportunities in most developing countries, finding employment is extremely challenging (e.g., in Ghana: Nyarko et al., 2014). Moreover, given that developing nations have high rates of unemployment and difficult labour markets (Affum-Osei et al., 2019), existing sociocultural and socioeconomic circumstances may affect the strategies employed during the job search process (Belle et al., 2021). Along these lines, exploring job search strategies in low- income countries (LICs) is relevant.

Consequently, our objectives are to (a) test how goal orientation relates to the strategies for searching for jobs, (b) test how the strategies for searching for jobs impact the outcomes of job search, and (c) test how self-control moderates the goal orientation—job search strategy relationship. First, by linking goal orientation and job search strategies, we offer a way of broadening our understanding and clarifying individuals’ perception about goal pursuit in quality job search strategies, a neglected but interesting relationship. Second, there is a suggestion that moderator variables could serve as a relevant boundary condition regarding the role of goal orientation in predicting other variables (Vandewalle et al., 2019). Therefore, we attempt to delineate how self-control may enhance or attenuate the impact of goal orientation on indicators of goal-directed job search behaviour. Third, although some researchers have explored several success criteria (Brasher & Chen, 1999), there is a limitation of convergent validity as most studies were conducted in developed countries (van Hooft et al., 2021). Consequently, we aim to make conclusions on some outcomes on job hunting and employment to expand the job search and employment success criteria beyond the dichotomous measure of employment success (i.e., when job seekers are asked if they are employed or unemployed : Brasher & Chen, 1999) in an understudied job-seeking population. Taken together, by undertaken the current research in African context, we explore the job search strategy as well as the success criteria constructs to facilitate its use in an under-studied population and wider job search contexts.

Theoretical development and hypotheses

Strategies for searching for jobs

Many aspects of behaviours that characterise the search for jobs have been explored in the extant literature (Blau, 1994; Van Hoye, 2018). The literature has identified goal-directed job search behaviour, namely FJSS, EJSS and HJSS, which are relevant in finding quality jobs (Crossley & Highhouse, 2005; Koen et al., 2016). People who employ focused search strategy have clear goals and high employment standards (Koen et al., 2010). Therefore, they screen job vacancies and apply to jobs, which meet their employment goals. People who search in a more exploratory manner have initial general objectives and are open to new and wider employment opportunities and apply to them (Stevens & Beach, 1996). Those who search more haphazardly have unclear goals and set low employment standards (Stevens & Beach, 1996). Such job seekers may use a “try and error” approach and may not have deliberate plans to sort job vacancies. Conceptually, both focused and exploratory search are tedious processes, which require high level of self-regulation (Taggar & Kuron, 2016). While focused and exploratory job search strategies are highly goal-directed, haphazard search strategy is less goal-directed (Okay-Somerville & Scholarios, 2022). Thus, these strategies drive different job search consequences (Van Hoye, 2018). In this study, we put forward that job seekers’ orientation in achievement situations holds important insights in explaining different job search strategies and subsequent employment outcomes.

Orientation towards employment goal

Goal orientation, which has become an essential construct in achievement motivation literature (DeShon & Gillespie, 2005), reflects individual differences in approaching and responding to situations in achievement settings (Dweck & Leggett, 1988). Goal orientation relates to people’s choice of tasks, efforts, persistence, creativity, strategy use, personal goal-setting and learning (Chadwick & Raver, 2015; Payne et al., 2007). Goal orientation was previously categorised into learning goal orientation (LGO) (described as the ability to acquire competence by mastering and understanding something new) and performance goal orientation (PGO) (described as the ability to acquire competence by gaining favourable judgements and blocking unfavourable judgements about one’s competence) (Dweck & Leggett, 1988). In recent years, researchers have categorised goal orientation into learning goal (LGO), performance-prove goal orientation (PPGO) and performance-avoid goal orientation (PAGO) (see Vandewalle et al., 2019). Individuals who adopt PPGO focus on the desire to demonstrate their competencies and gain favourable judgements from others. On the other hand, individuals who adopt PAGO are more likely to avoid demonstrating their abilities and what they are capable of doing to avoid occasions where unfavourable evaluations may emerge. Regarding the above three categories of orientation to goal (Elliot, 1999; Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996; Vandewalle et al., 2019), LGO and PPGO are categorised as approach-goal orientations because they focus on the possibilities of success and positive outcomes (Elliot & Church, 1997; Wang & Yan, 2018). On the contrary, given that performance-avoid individuals are more likely to anticipate unfavourable outcomes and failures, they are categorised under avoidance-goal orientation (Elliot & Thrash, 2002; Elliot, 1999; Vandewalle et al., 2019). To examine alternative and more nuance effects of goal orientation, we explore the interrelations amongst goal orientation and the three types of job search strategies.

Approach-goal orientation and job search strategies

Recent research on goal orientation hypothesises that a high level of LGO leads to more optimal performance outcomes (Miron-Spektor et al., 2021). It follows that people with LGO are malleable, which predisposes them to develop quality skills and ideas (Chadwick & Raver, 2015; Fisher & Ford, 1998). These attributes predispose learning-approach goal oriented people to seek feedback and sustain high productivity (Miron-Spektor et al., 2021). PPGO individuals are also willing to set high goals to gain favourable judgements from others (Wang & Yan, 2018). Thus, both LGO and PPGO individuals seek to perform favourably during goal pursuit (Vandewalle et al., 2019). Given that both focused and exploratory job searches are difficult, challenging, and also relate to positive consequences (Affum-Osei et al., 2021), the probability for LGO and PPGO job-seekers to use FJSS and EJSS is higher than using HJSS. Studies support that job seekers with high LGO persist in the events of failures (Yamkovenko & Hatala, 2014) and engage in cognitive reaapraisal strategies towards finding jobs (Wang & Yan, 2018). Similarly, reseach shows that PPGO relates positively to career exploration (Creed & Hennessy, 2016), and cognitive job search reappraisal strategies (Wang & Yan, 2018). Thus, high approach-goal oriented job seekers may employ goal-directed job search strategies in the employment process.

Hypothesis 1a

Both LGO and PPGO relate positively to FJSS.

Hypothesis 1b

Both LGO and PPGO relate positively to EJSS.

Hypothesis 1c

Both LGO and PPGO relate negatively to HJSS.

Avoidance-goal orientation and job search strategies

Individuals who adopt PAGO have fixed mindset and view skill development as challenging and less feasible (Dineen et al., 2018). PAGO includes temperaments, which may be associated with major affective disorders (Baldessarini et al., 2017). Performance-avoid individuals believe that failures and challenges are characteristics of low abilities and perceive their capabilities as unchangeable (Elliot, 1999). Individuals adopting PAGO perceive setbacks and failures as indicators of low ability (Kozlowski et al., 2001). PAGO job seekers tend to show avoidance-oriented responses such as procrastination and anxiety during the pursuit of employment goals (Kanar, 2017).

We argue that because FJSS and EJSS are challenging tasks which require extensive self-regulation including high levels of decision-making processes of sorting and evaluating alternative job openings (Koen et al., 2016), individuals who adopt PAGO may decrease their interest in performing them. Such job seekers have a high probability to use the try-and-error approach to get employment more quickly to avoid the negative judgements associated with unemployment. In addition, HJSS may serve PAGO job seekers’ job search purpose, because when they are performing poorly, they can reason that they have applied for a large number of job openings (Taggar & Kuron, 2016). Such job seekers avoid to be perceived as incompetent and ineffective (Payne et al., 2007). These findings confirm the assertion that those who adopt PAGO may employ poor job search strategies, which are coupled with mistakes and failures rather than engaging in effective strategies (Noordzij et al., 2013). Consequently, PAGO decreases effective strategies (Creed et al., 2009), relates positively to job search anxiety (Kanar, 2017), and career distress (Creed & Hennessy, 2016). Thus, performance-avoid orientation focuses on poor strategies and negative outcomes (Porath & Bateman, 2006; Vandewalle et al., 2019).

Hypothesis 2a

PAGO relates negatively to FJSS.

Hypothesis 2b

PAGO relates negatively to EJSS.

Hypothesis 2c

PAGO relates positively to HJSS.

The strategies for searching for Jobs and the unfolding process of job search

Several job search success criteria have been operationalised in the job-hunting and employment literature (Saks, 2006). Employment status has become the most reported success criterion (Kanfer et al., 2001). However, there are several factors, which may determine employment status. Research highlights the unfolding process of job search (Turban et al., 2013; Vansteenkiste, Verbruggen, & Sels, 2016), which suggests that for job seekers to obtain employment they must be successful in engaging in job search activity, attending interviews, corporate interactions, and accepting job offers. This paper investigates three strategies that job seekers employ as well as three sequential outcomes namely, how many interviews attended, the number of appointment received, and employment status (i.e., whether or not a job seeker has received employed). Following prior study (Turban et al., 2013), it is posited in this paper that the three job search strategies will relate to the quantity of interviews, which in turn relate to quantity of offers, which in turn leads to employment status.

First, FJSS involves a deliberate effort to screen and search for a smaller number of potential employers, which meet the job seeker’s specific criteria. Job seekers who employ focused search strategy narrow their applications to meet their top employment choices (Stevens & Beach, 1996). Conceptually, those who search in a more focused way are less likely to send many job applications (Taggar & Kuron, 2016), which implies a smaller quantity of job interviews and offers (Stevens & Beach, 1996). As a result, FJSS is likely to elicit more positive outcomes such as obtaining stable employment. Similarly, Taggar and Kuron (2016) reported that the use of FJSS facilitates a fewer number of job applications. Additionally, it has been posited by Crossley and Highhouse (2005) that FJSS led to attending fewer job interviews, and fewer offers.

Second, EJSS involves the extent to which a job seeker considers several alternative employment opportunities and remains keen to applying to them. Individuals who approach the job search process with EJSS are motivated to collect a larger number of information to learn about different job opportunities (Stevens & Beach, 1996). Given that this type of job search strategy considers several possible job alternatives (Stevens & Beach, 1996), it should increase job applications, interviews attended, and offers received (Koen et al., 2010; Taggar & Kuron, 2016). Consequently, EJSS strategy has been found to promote higher quantity of job applications (Taggar & Kuron, 2016) offers (Crossley & Highhouse, 2005), and employment status (van Hooft et al., 2021).

Third, HJSS involves the degree to which a job seeker searches for jobs without a deliberate plan for screening employment options or carefully weighing different opportunities (Koen et al., 2016). Haphazard job seekers hunt jobs without rationale and are more likely to gather information passively because they have low standards and fussy search plans (Crossley & Highhouse, 2005). HJSS drives debilitating job search and employment outcomes (Konstam et al., 2015). Empirical research indicates that HJSS decreases the quantity of job applications (Taggar & Kuron, 2016), offers received (Crossley & Highhouse, 2005), and employment success (Koen et al., 2016). Based on the above discussions, the following are proposed:

Hypothesis 3a

FJSS relates negatively to the number of job interviews.

Hypothesis 3b

EJSS relates positively to the number of job interviews.

Hypothesis 3c

HJSS relates negatively to the number of job interviews.

Hypothesis 4

The total number of job interviews attended correlates positively with the number of job offers, which in turn relates positively to employment status.

The strategies for searching for jobs and quality employment

There has been less attention to post-employment job outcomes, in particular, on the quality of employment amongst previously unemployed workers (Virick & McKee-Ryan, 2018). Importantly, scholars have advocated for moving beyond quantity search outcomes (e.g., quantity of applications) to more quality outcomes (e.g., employment fit) (e.g., van Hooft et al., 2013). This is because underemployment and turnover are more likely when job seekers accept less optimal jobs (Virick & McKee-Ryan, 2018). Job search intensity increases employment status, but research on its relationship with quality employment has been sparse and inconclusive (van Hooft et al., 2021; Wanberg et al., 1999). We capture quality employment in terms of fit perceptions of job seekers in their organisations, their satisfaction and the intentions to quit or remain in their organisations (Brasher & Chen, 1999; Cable & DeRue, 2002; Crossley & Highhouse, 2005; Saks & Ashforth, 2002). Thus, we include fit perceptions, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions (i.e., employment quality) to assess quality jobs after employment (Koen et al., 2010).

Research distinguishes three indicators of fit perceptions: person-organisation fit (P-O fit: describes whether job seekers’ values are similar to the characteristics of the organisation such as the organisation’s culture), demand-ability (DA) fit (describes the congruence between a worker’s ability and what is expected from his/her job), and need-supply (NS) fit (describes workers’ fit between their rewards and their outputs to the organisations they work for (Cable & DeRue, 2002). This study proposes that the three types of strategies for searching for employment will positively associate with the job search quality dimensions. Given that focused search strategy involves careful screening and narrow applications to employment options, we expect it to lead to quality jobs (Affum-Osei et al., 2021). Studies show that those who use focused search are more satisfied, have good fit with their jobs and have less turnover intentions (Affum-Osei et al., 2021; De Battisti et al., 2016).

As discussed earlier, those who employ more EJSS are motivated and dedicated to fully explore their employment options and aim at securing quality jobs (Crossley & Highhouse, 2005; Koen et al., 2010). For example, while Crossley and Highhouse (2005) reported that EJSS relates positively to job satisfaction, Koen et al. (2010) reported negative relationship with intentions to quit. Finally, individuals who search haphazardly are more likely to accept first jobs offered because such job seekers have low job standards and unclear employment goals. Thus, HJSS is likely to lead to poor job satisfaction, poor fit perceptions, and high turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 5

FJSS relates positively to (a) P-O fit (b) D-A fit, (c) N-S fit (d) job satisfaction, and is negatively associated with (e) turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 6

EJSS relates positively to (a) P-O fit (b) D-A fit, (c) N-S fit (d) job satisfaction, and is negatively associated with (e) turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 7

HJSS relates negatively to (a) P-O fit (b) D-A fit, (c) N-S fit (d) job satisfaction and is positively associated with (e) turnover intentions.

The moderating role of self-control

Self-control is an important trait, which enables individuals to override and regulate dominant response tendencies such as desires, impulses, thoughts, attention, emotions, and behaviour (Tangney et al., 2004). It prompts the capacity to pursue long-term goals (Van Hooft & Kreemers, 2021) and has been found to be associated with subjective well-being (Massar et al., 2020). According to De-Ridder et al. (2012), self-control may generally be stronger in some individuals than others. Thus, we conceptualise self-control as a trait. Research shows that there are trait deviations in self-control in respect to individuals’ behaviour (De-Ridder et al., 2012).

We contend that self-control may interact with goal orientation to predict job search strategies because of two crucial cognitions: first, the ability of job seekers to initiate and amplify goal-directed behaviours and second, the urge of job seekers to inhibit and restrain undesirable responses, which may alter goal pursuit (Baumeister et al., 1994). Research shows that people are motivated to perform behaviours, which are attractive and have valued outcomes (Van Hooft & Kreemers, 2021). On the other hand, people are less motivated and may refrain from unattractive behaviours with unvalued outcomes (Van Hooft & Kreemers, 2021). Consequently, people with high self-control engage in difficult and complex tasks and are more likely to focus on long-term goals (De-Ridder et al., 2012). Thus, self-control is relevant and urgent in the job search process (Van Hooft et al., 2013). People who show high levels of self-control regulate their emotions and concentration relative to individuals who exhibit low levels of self-control (Baumeister et al., 2018). Highly self-controlled people have the capacity to override attractive and unbeneficial behaviours (Baay et al., 2014).

Taken together, because high levels of self-regulation tactics help to promote desirable outcomes (De-Ridder et al., 2012), it appears that job seekers with approach orientation may undertake favourable job-seeking behaviours (i.e., FJSS and EJSS) because they can initiate goal-directed strategies. In a similar manner, they can control their impulses to inhibit poor job search strategies such as HJSS, which may lead to unfavourable outcomes. More specifically, we contend that the link between approach goal orientations (LGO and PPGO) and strategies for searching for jobs will be stronger for job seekers with higher self-control. On the other hand, high levels of self-control could compensate for anxiety, threat construal, and procrastination characterised by PAGO. We contend that the negative association between PAGO and FJSS as well as EJSS could be dampened by high levels of self-control. It is not surprising that self-control has been found to relate positively to work-related behaviour (Van Hooft & Kreemers, 2021), and job search behaviour (Baay et al., 2014).

Hypothesis 8a

Self-control moderates the positive impacts of LGO and PPGO on FJSS such that the impacts are stronger for job searchers who have higher levels of self-control.

Hypothesis 8b

Self-control moderates the positive impacts of LGO and PPGO on EJSS such that the impacts are stronger for job searchers who have higher levels of self-control.

Hypothesis 8c

Self-control moderates the negative impacts of LGO and PPGO on HJSS such that the impacts are stronger for job searchers who have higher levels of self-control.

Hypothesis 9a

Self-control moderates the negative impact of PAGO on FJSS such that the impact is weaker for job searchers who have higher levels of self-control.

Hypothesis 9b

Self-control moderates the negative impact of PAGO on EJSS such that the impact is weaker for job searchers who have higher levels of self-control.

Hypothesis 9c

Self-control moderates the positive impact of PAGO on HJSS such that the impact is weaker for job searchers with high levels of self-control.

Methods

Participants and procedures

We collected data at three-time points from unemployed young adults who were actively seeking employment in Ghana. The focus on job seekers for the study’s sample stems from recent public discourse on youth unemployment in Ghana. Data show a strong economic performance of Ghana’s economy with an estimated 9.3% growth in gross domestic product in 2017 (Word Bank, 2018). Ghana was named as one of the largest destinations for foreign direct investment in sub-Sarah Africa between 2017 and 2019 (World Bank, 2018). However, growth has not translated into employment and job creation amongst young adults, raising concerns about the quality of the country’s economic growth (World Bank, 2016). The unemployment situation worsened by the coronavirus 2019 (McFarland et al., 2020) has also created a difficult labour market in terms of securing employment in the country (Nyarko et al., 2014). In such labour markets, self-regulation, career adaptability, and ambidextrous behaviour are critical for a smooth school-to-work transition (Affum-Osei, Antwi, et al., 2019). Hence, research, exploring goal orientation and job search strategies to equip them for successful employment is relevant and timely.

The research was conducted in collaboration with employment agencies, which provide employment guidance and routine recruitment services to job searchers. The aims of the research were explained to the job seekers and we also obtained informed consent from each of the participants before the survey questionnaires were administered to them. Participation in the surveys was voluntary and no incentives were provided.

The research team distributed 984 surveys (Time 1) to the job seekers. Consequently, 878 (a response rate of 89.2% at Time 1) was received. Among them, 19 participants were deleted because of missing data (i.e., 5% and above missing at random cases of survey questions were excluded: see Allison, 2003). The same criterion was used for the other two waves. To decrease common methodology bias (CMB: Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003), participants were invited to complete a follow-up survey (Time 2) six weeks later, after they were done with Time 1 survey. A total of 724 respondents returned their surveys. Respondents with many incomplete data of the survey items were deleted (n = 4), giving rise to 720 participants (Time 2: 84% response rate). The survey at Time 3 was then conducted six months after Time 2 to allow for enough time for participants’ to search for jobs. The Time 3 survey administration led to 440 completed surveys. After we deleted missing and incomplete records (n = 22), resulted in 418 participants in the final sample (i.e., 58% response rate at Time 3), for examining the study’s hypotheses. Out of these usable questionnaires, 267 (63.9%) were males, 151 (36.1%) were females and 208 (49.8%) had completed bachelor’s degrees. The participants have average unemployment length of 7 months, with a mean age of 27 years.

Study’s measures

A 5-point Likert scale was employed (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) for all responses of the measures unless otherwise stated. We measured demographic characteristics, and goal orientation at Time 1 and self-control, and strategies for searching for jobs at Time 2. Time 3 variables include quantity of interviews attended, job offered, and chance of being employed, fit perceptions, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. The English language was used to administer all the items.

Goal Orientation (Time 1). Vandewalle’s (1997) 13-item goal orientation scale adopted from Creed et al. (2009) was employed to assess goal orientation. Five items were used to capture LGO, four items captured PPGO and four items assessed PAGO. An example of the itmes is “I enjoy it when others know how well I am doing in my job search”. The reliability coefficients for this study were 0.81, 0.71, and 0.86 respectively.

Job Search Strategy (Time 2). We used the 16-item job search strategy scale (Crossley & Highhouse, 2005), which has been validated in other studies (Affum-Osei et al., 2021; Priyadarshini et al., 2021) to measure job search strategies. Focused and exploratory strategy consisted of 6 items each and haphazard strategy consisted of 4 items. An example is “I gather as much information about all the companies that I could.” The internal consistency of the itmes (i.e., Cronbach’s alphas) were 0.81, 0.84, and 0.85 respectively.

Self-control (Time 2). We assessed self-control using the 13-item scale from Tangney et al. (2004), which has been found to be reliable and valid (Hagger et al., 2018). An example of the items is “I am able to work effectively toward long-term goals” (1 = Not at all to 5 = Very Much). We obtained Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.84.

Number of Job Interviews attended and Job Offers (Time 3). Participants of the survey recorded the quantity of job interviews attended and job offers obtained within the six-month period of job-hunting. These assessment procedures were consisted with prior research (Stevenor & Zickar, 2022).

Employment Status (Time 3). Participants indicated their employment status by reporting whether or not they have obtained employment (0 = unemployed, 1 = employed) (e.g., Amato et al., 2016; Guan et al., 2013; Saks, 2006).

Fit Perceptions (Time 3). We measured fit perceptions with a 9-item scale (Cable & DeRue, 2002). P-O, D-A and N-S fit were assessed with 3-items each. An example is “The job that I currently hold gives me just about everything that I want from a job”). The alpha coefficients for this study were 0.88, 0.88, and 0.89 respectively.

Job Satisfaction (Time 3). Participants’ satisfaction for jobs was assessed using a 3-item scale (Cammann et al., 1983: The Michigan Organisational Assessment Questionnaire). A sample item is “All in all; I am satisfied with my job”. We obtained alpha coefficient of 0.81 for this study.

Turnover Intentions (Time 3). We used the 3-item scale by Colarelli (1984) to assess turnover intentions. The measure has also been used by Koen et al. (2010) and Saks and Ashforth (2002). An example is “If I have my own way, I will be working for another organisation one year from now.” The alpha coefficient for this study was 0.87.

Control Variables (Time 1). The control variables include gender, age, education, job search context, and unemployment length because they are related to strategies for searching for jobs and behaviour (Kanfer et al., 2001). This procedure corroborates previous job search research (e.g., Wanberg et al., 1999). For example, job search context (e.g., new entrants, and job losers) has been related to the intensity of job seeking and employment outcomes (Boswell et al., 2012).

Analytical Approach

The data were analysed using Mplus 7.4 software (Muthén & Muthén, 2015) with Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE). We used the two-step structural equation modelling (SEM) procedure (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted at the fist stage to obtain the conceptual distinctness of the measures. For uniformity, easy presentation and interpretation, we parcelled the items of each latent factor to form three indicators following the item-to-construct balance procedure, which has been put forward by Little, Cunningham, Shahar, and Widaman (2002). In this process, items were assigned based on loadings to form composite indicators on three anchors (Lim et al., 2016). Parcelling minimises measurement error and improves model fit (Little et al., 2002). Parcelling also aids stable parameters, simplification of model interpretations, provides definite rational results and decreases violation of normality (Hau & Marsh, 2004).

In testing the research hypotheses, we estimated the logistic SEM by employing Monte Carlo integration procedure (Muthén & Muthén, 2015), which allows models with dichotomous variables (i.e., the employment status measure) (Muthén & Muthén, 2015). First, the analysis between the major variables for the research focused on all the Time 3 participants (N = 418). Second, due to small sample size, we performed path analysis for the association between strategies of searching for jobs and quality employment measures (i.e., fit perceptions, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions) using the job seekers who had obtained employment at Time 3 (n = 137). The goodness-of-fit of the models was assessed with multiple fit indices (e.g., Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Chi-square (χ2) statistics) (for details see Hu & Bentler, 1999). Additional indices (i.e., log-likelihood ratios : Δ-2LL), suggested by Satorra and Bentler (2010) were utilised for model comparisons.

To test the proposed moderation effects (see Table 1 for the moderation results), we estimated the moderation model, which specified the latent interactions between goal orientation and self-control and their effects on job search strategies (Mathieu et al., 1992). We fixed the paths of the product terms of alternative model to zero and compared it with the proposed moderation model. The research results revealed that the moderation model showed better fits compared to the main-effect model, which did not include the interaction effects (Δ-2LL [27] = 106.23, p < .001). We then plotted the simple slopes.

Results

Descriptive statistics

As shown in Table 2, we provide mean values, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, and correlations for the study’s variables.

Measurement model testing

We conducted measurement models on the overall sample [χ2 (168), N = 418) = 475.80, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05] and the job seekers who had obtained employment [χ2 (80), N = 137) = 127.50, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.07]. The proposed measurement models were then compared to the alternative models, which were better than all the alternative models suggesting that the focal constructs are distinct within them and across the different time points. Table 3 shows the results of the measurement models.

Structural model testing

First, we performed SEM on the hypothesised model and alternative model without fitting the logistic integration to ascertain the traditional model fit indices. Both the hypothesised and alternative models showed acceptable fit: hypothesised model [χ2 (250, N = 418) = 657.91, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.88, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.06]; alternative model ([χ2 (235, N = 418) = 614.14, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.88, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.04]). The fit of the alternative model was not better than that of the hypothesised model: Δχ2 (15) = 43.77, p = .54. We then based our analyses on the original hypothesised model to follow the principle of parsimony. Second, the logistic hypothesised model with the robust integration was fitted to the data and compared with the alternative model. The likelihood ratio test (-2LL), which works by comparing the fit between two statistical logistic models was used (Pituch & Stevens, 2016). The results revealed that the alternative logistic model was not better than the hypothesised model (Δ-2LL [9] = 8.21, p = .53). Therefore, hypothesised model is more likely to fit the data than the alternative model.

Due to small sample size (i.e., n = 137), path model was adopted to test the set of hypotheses on those who secured employment. The hypothesised model based on those who had obtained employment derived satisfactory fit indices [χ2 (18), N = 137) = 26.95, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.03].

Hypotheses testing

Direct relationships

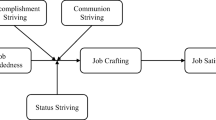

Based on our results (see Fig. 1), LGO relates positively to FJSS (β = 0.40, p < .01), EJSS (β = 0.29, p < .01), and negatively to HJSS (β = − 0.37, p < .01). PPGO relates positively to EJSS (β = 0.19, p < .05), but the relations between PPGO and both FJSS (β = − 0.04, p = .40) and HJSS (β = 0.02, p = .79) were not significant. Therefore, H1a and H1c were partly supported and H1b was fully supported. PAGO relates negatively to FJSS (β = − 0.38, p < .01), EJSS (β = − 0.18, p < .05), and positively to HJSS (β = 0.23, p < .01). Thus, H2a-c were fully supported. Overall, the model explained 43% variance in FJSS, 21% in EJSS, and 26% in HJSS.

Results further show that EJSS positively correlates with the number of job interviews (β = 0.12, p < .05), HJSS relates negatively to the number of job interviews (β = − 0.13, p < .05), but FJSS was unrelated to job interviews (β = 0.03, p = .55). The number of job interviews was positively associated with the number of job offers (β = 0.42, p < .01), which in turn was positively related to employment status (β = 0.88, p < .01). The odds ratio was significant for the number of job offers (Exp (B) = 66.58, p < .05), indicating that for a one-unit increase in job seekers’ number of job offers, they were 66.58 times more likely to be employed.

These findings support H3b, H3c and H4 but H3a was not supported. Overall, the model explained 6% variance in the number of interviews, 20% in number of job offers, and 79% in employment status.

Relationship between job search strategies and employment quality

Regarding the relationship between the strategies for searching for jobs and employment quality (see Fig. 2), the results revealed that FJSS positively relates to P-O fit (β = 0.22, p < .01), D-A fit (β = 0.26, p < .01), N-S fit (β = 0.40, p < .01), job satisfactions (β = 0.29, p < .01), and negatively to intentions to quit (β = − 0.50, 2p < 0.01). Therefore, H5a-H5e were fully supported. Moreover, the use of EJSS positively relates to person-organisation fit (β = 0.34, p < .01) and job satisfaction (β = 0.29, p < .01) but unrelated to the D-A fit (β = 0.12, p = .13), N-S fit (β = 0.09, p = .29), and turnover intentions (β = − 0.03, p = .66). Hence, H6a and H6d were supported but H6b, H6c and H6e were not supported. Finally, HJSS relates negatively to person-organisation fit (β = − 0.19, p < .05), D-A fit (β = − 0.45, p < .01), job satisfaction (β = − 0.15, p < .10), and positively to intentions to quit (β = − 0.27, p < .01), and not related to N-S fit (β = − 0.11, p = .231). Therefore, H7a, H7b, H7d and H7e were supported but H7c was unsupported. The hypothesised model contributed more than 22% of the variance in P-O fit (R2 = 0.22), N-S fit (R2 = 0.22), and job satisfaction (R2 = 0.25), and more than 30% of the variance in D-A fit (R2 = 0.32), and intentions to quit (R2 = 0.38%).

Results of the path analyses of job search quality. Standardised coefficients are reported, solids lines represent significant paths. Dash lines indicate non-sufficient paths. LGO = Learning goal orientation, PPGO = Performance-prove goal orientation, PAGO = Performance-avoid goal orientation, P-O fit = Person-Organisation, D-A fit = Demand-Ability fit, N-S fit = Need-Supply fit. n = 137, †p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01

The moderation hypotheses

According to the results, self-control and LGO interact significantly with FJSS (β = 0.13, p < .05), and HJSS (β = − 0.24, p < .05) but is unrelated to EJSS (β = − 0.04, p = .50). Thus, H8a and H8c were partially supported but H8b, and H9a-H9c were not supported.

Based on the simple slopes, LGO negatively correlates with FJSS (B = 0.47, p < .01), when self-control is high (+ 1 SD) and when self-control is low (− 1 SD), LGO was weakly related to FJSS (B = 0.23, p < .05: see Fig. 3). With stronger LGO, individuals used focused strategies more often because of their better self-control levels. Thus, those with high self-control and adopt LGO stand the chance to employ high-quality job search strategies.

Additionally, when there was high self-control (+ 1 SD), LGO was significantly and negatively related to HJSS (B = − 0.44, p < .01), but when there was low self-control (− 1 SD), LGO was unrelated to HJSS (B = − 0.04, p = .53: see Fig. 4). A decrease in HJSS was observed among those with LGO and better self-control.

Discussion

This current study, we focused on goal orientation and self-control to explain the three types of job-seeking strategies and subsequent employment outcomes. Our results suggested that people who adopt approach-goal orientations consider FJSS and EJSS but not HJSS as effective job search paths to secure employment and quality jobs. On the other hand, HJSS was found to be more attractive to performance-avoid oriented job seekers.

In addition, we expected that self-control could enhance beneficial job-hunting strategies and buffer detrimental job search strategies to underscore the relevance of self-regulation in the employment pursuit (van Hooft et al., 2021; Vansteenkiste et al., 2016). In particular, self-control moderated the links between LGO and FJSS and also HJSS. Specifically, a positive relation between LGO and high quality job search strategies was found for job seekers with higher self-control, while a negative relationship was found for those with lower self-control. The results reinforce the idea that self-control could provide a substantial benefit to job-hunters to search more effectively toward employment (Baay et al., 2014). Moreover, indicators of job-hunting strategies were expected to drive the outcomes of job search and employment. In particular, the use of FJSS and EJSS contributed substantially to finding employment and post-employment quality. On the contrary, HJSS was negatively associated with the chance of securing employment and post-employment quality. Overall, our findings strengthen research on the unfolding model of job searching strategies and contributes to calls to examine quality job search (Kreemers et al., 2021; Van Hooft et al., 2013).

Theoretical implications: goal orientation

According to our findings, LGO facilitated quality strategies for searching for jobs and PAGO was found to utilise poor ways for searching for jobs. Furthermore, while the results of PPGO were inconsistent with what was expected, they showed some positive effects in predicting job search strategies. These findings corroborate the general assumption and findings in goal orientation research (Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996; van Hooft, 2014) and highlight the importance of mastery goal in job search (Ali et al., 2016). On the other hand, PAGO drives people to search more haphazardly but less focused and exploratory. Perhaps, the tendency for performance-avoid oriented individuals’ desire to avoid situations, which could lead to incompetency (VandeWalle & Cummings, 1997) prompts them to use try-and-error approach during job search. This is because FJSS and EJSS demand arduous task with self-regulation of sorting and fully exploring job alternatives (Crossley & Highhouse, 2005). Consequently, FJSS and EJSS may be fundamentally aversive and challenging for job seekers who adopt PAGO (Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996). The results confirm further that while PAGO individuals are more inclined to the possibility of failure, both LGO and PPGO individuals are inclined to achieving success (Payne et al., 2007). It highlights that people who work toward specific difficult tasks (e.g., focused search) perform better than those who just do their best (e.g., haphazard search) (van Hooft, 2014). Therefore, job seekers may stand the chance to optimise their performance by adopting performance-approach goal orientation and disregarding performance-avoid goal orientation (Vandewalle et al., 2019).

Theoretical implications: self-control

The incorporation of self-control stems from the recommendation that moderators can provide a stronger foundation to explain goal orientation and distal outcomes (Vandewalle et al., 2019). Our findings demonstrate that self-control strengthens the positive and weakens the negative effects of LGO on FJSS and HJSS respectively. This result is consistent with the perspective that self-control provides capacity to help individuals to override dominant behavioural tendencies (Baumeister et al., 2018; Van Hooft & Kreemers, 2021) to make decisions that have long-term implications rather than short-term benefits (Baay et al., 2014).

Indeed, the data reveal that learning goal-oriented individuals who showed higher levels of self-control were likely to secure long-term jobs. Such individuals may sacrifice behaviours (e.g., HJSS) that may lead to short-term consequences in favour of those, which will enhance long-term interest (De-Ridder et al., 2012). The implication is that job seekers controlled their impulses for immediate and poor employment by resisting the temptation to search more haphazardly. Thus, our results confirm the stop- and start‐control (Van Hooft & Kreemers, 2021) and support the promotion of action that leads to higher pay-off in the long-run (Carver & Scheier, 2002). For instance, high self-control behaviours facilitate the inhibition of undesirable behaviour when people have higher LGO, enhancing beneficial job search behaviours. In other words, self-control provides contingencies necessary for enhancing or attenuating job search strategies depending on job seekers’ goal orientation (Kanar, 2017). The findings corroborate prior research (Baay et al., 2014), which suggests that those who show higher self-control levels have the capacity to override poor job-seeking bahaviours.

Theoretical implications: strategies for Job Searching and employment outcomes

With respect to the outcomes of strategies for searching for jobs, our findings showed that FJSS was unrelated to interviews attended, and EJSS contributed to interviews attended by job seekers. Our results show that exploratory search behaviour is rewarding when it comes to the quantity of interviews attended. These findings corroborate prior assumption that EJSS may be the best way to deal with difficult labour markets with high unemployment rates (Koen et al., 2016). On the contrary, HJSS decreased interviews attended. This is because HJSS seekers have fuzzy ideas about what they want, they may therefore attend fewer interviews, accept fewer offer, and poor jobs (Konstam et al., 2015). Such individuals are more likely to accept the first available offer (Affum-Osei et al., 2021). The results revealed that job seekers who searched in a more exploratory manner received more invitations to be interviewed, which led to more offers and a higher probability of securing a job. This result confirms the unfolding process of job search in understudied population (Turban et al., 2013). By these findings, this study extends research on job search intensity to include dimensions on how initial job search success may affect later success (e.g., Turban et al., 2013).

The study highlights that quality job search strategies are particularly relevant during the job-hunting process because they help job seekers to secure quality jobs. Our results are consistent with studies (e.g., Hoye & Saks, 2008; Saks, 2005), which suggest that different strategies elicit different outcomes. Firstly, FJSS contributed to the likelihood of obtaining quality jobs in terms of fits, and job satisfaction. This result supports previous findings that job searchers with clear and specific employment goals were more likely to obtain quality employment (Kreemers et al., 2021). In fact, individuals are encouraged to employ FJSS when the goal of job search is to obtain quality jobs (Koen et al., 2010). For example, Saks and Ashforth (2002) reported positive relationship amongst quality job search, job satisfaction and person-job fit.

Secondly, results showed that EJSS is relevant to P-O fit and job satisfaction. While this finding corroborates Crossley and Highhouse (2005) finding, it contradicts that of Koen et al. (2010). These contradictory findings may be due to the sample and the context within which these studies were undertaken. For instance, while we sampled unemployed job seekers in a difficult labour contexts (Affum-Osei et al., 2019) Koen et al.’s, (2010) study was on unemployed adults seeking reemployment and Crossley and Highhouse (2005) focused on individuals who were already working. Additionally, in our employment context with relatively low employment opportunities, job seekers may be content with their current jobs and perceive them to be satisfying, especially when they are aware that majority of the young adults are without jobs. Thus, the type of unemployment context may explain the trend of effects of EJSS on post-employment quality (Koen et al., 2010). Third, HJSS drives detrimental employment outcomes. It reduces the chance of getting interviews, led to poor fit perceptions, and a high probability to quit. These results corroborate the assumption that job-seeking individuals who adopts HJSS have fuzzy ideas, undecided and may apply to job openings which are above their qualifications (Stevens & Turban, 2001). It follows that the lack of employment fit associated with HJSS may expose them and consequently decrease their job satisfaction (Crossley & Highhouse, 2005).

Practical implications

Unemployment continues to be a major social and economic problem especially in developing countries. Consequently, career development and policymakers have shown considerable concerns towards job seekers’ self-regulation, motivation, and their search behaviour (Kreemers et al., 2021; van Hooft et al., 2021). Our findings contribute to policy and practice in myriad ways. First, given that LGO positively impacts the activities of job seekers, it is worthwhile for career counsellors to equip job seekers to be confident and adopt mastery orientation during the employment process. Such intervention could take the form of assisting job seekers to identify their strengths and weaknesses aiming to pinpoint areas which require improvements. For example, career counsellors should explore the search objectives of job seekers and help them choose the behaviours, which could lead to the achievement of the selected goals. On the contrary, PAGO leads to detrimental behaviour. For instance, research shows that personality characteristics including PAGO may lead to risky and unbeneficial behaviours including risk driving (Pompili et al., 2012) and poor job search efforts (Vandewalle et al., 2019). Thus, it is important for career counsellors to assist job seekers to regulate their activities towards LGO. Second, diverse criteria exist for job seekers to achieve specific job search success (Hoye & Saks, 2008; Van Hoye, 2018). Hence, practitioners should help to train job seekers on the quality job search behaviours. It implies that job search and employment goals are not only crucial for self-regulation and motivation reasons but also have implications for the type of job search activities (Okay-Somerville & Scholarios, 2022).

Third, there are a lot of rejections and failures associated with job search, which may drain job seeker’s energy during the job search process (Lim et al., 2016). Thus, another way of assisting them is through interventions to enhance their self-control. Such intervention should include capabilities to monitor progress and performance, learn from failures, adjust job search strategies, control impulses, and increase search intensity (Noordzij et al., 2013). Interventions could also focus on how unemployed people could cope with the unemployment situation by engaging in more focused-coping strategies (Stevens & Beach, 1996). For example, job seekers could be encouraged to join Job Clubs, which are forms of intervention to help them secure jobs through equipping them with interview skills, self-presentation skills, internet search strategies, networking, time and stress management (e.g., Nakai et al., 2018). Additionally, universities should be encouraged to create international mobility programmes for young adults, which could help promote job seeker’s self-efficacy (Emirza et al., 2021). Finally, the results have implications for employers in terms of person-organisational fit (Swider et al., 2015). Specifically, the findings may inform recruiters with regards to the development of proper assessment tools for the purpose of employees recruitment and selection in organisations (da Motta Veiga & Turban, 2014). For example, job interviews could be based on the job search activities, which the applicants used in the search process. This will aid career assessors to havebetter understanding about job searchers’ fit perceptions about the jobs they apply for as well as the organisation they prefer to work with.

Limitations and directions for future research

Although, we collected the data in three-time points and achieved a considerable response rate, the results are not without limitations. First, we used survey questionnaires to measure all the variables. This may suggests a possibility of common method bias (CMB; Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, we used widely reliable and valid self-report measures to minimise the biases (e.g., Crossley & Highhouse, 2005; Vandewalle, 1997) and respondents were also assured of their confidentiality. In addition, our descriptive statistics (e.g., correlations) among the variables, which were collected at the same time varied considerably within the threshold showing that the challenge of CMB is minimised in this study. Furthermore, the three-time data collection design could decrease the risks of CMB (Podsakoff et al., 2003). For example, we assessed our outcome variables more than five months after the prior wave of data collection, which should provide enough time interval to achieve internal reliability and validity of the survey measures. Nonetheless, future research should use multiple methods including interviews and experimental procedures to complement questionnaires to assess the key variables in this study. Furthermore, well-crafted story-telling about people’s work and educational experiences (e.g., Smart & DiMaria, 2018) could also be used to explore the job search strategies.

Second, job search takes different forms and phases which makes it a dynamic process. Thus, it is possible that job searchers may vary their goals and strategies during the employment process. For example, a job seeker may start the process by searching more exploratory, but search less exploratory and more focused after she/he has become familiar of what they actually want. Future studies should examine multiple waves of data to capture these changes overtime during the job search process. Thirdly, the 6-month period allowed to search for jobs was relatively short for the job seekers. The duration of job search is relatively shorter in other employment context (e.g., Australia: cf.: Amato et al., 2016; Creed et al., 2009) compared to the Ghanaian context (Affum-Osei et al., 2019). Thus, the situation might not be the same for difficult labour markets as Ghana, where the average length of unemployment of this study was seven months. Therefore, researchers should consider allowing a relatively longer period of time when exploring predictors of job search outcomes in restricted employment contexts.

Taken together, the current study was based on participants with unique characteristics in terms of social, cultural, and economic, thus care should be taken in the generalisability of the results. Most of the participants have been unemployed for over five months. Thus, one may also speculate that the labour market conditions may have impact on the choice of job seeker’s job search strategies since they were not assigned to specific job search strategies. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted within the context of the current study. Future studies should expand the current findings to other populations to further examine the importance of self-control, orientation of goals, and strategies for searching for jobs during the job hunting process.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Affum-Osei, E., Antwi, C. O., Abdul-Nasiru, I., Asante, E. A., Aboagye, M. O., & Forkouh, S. K. (2019). Career adapt-abilities scale in Ghana: Psychometric properties and associations with individual-level ambidexterity and employees’ service performance. Current Psychology.

Affum-Osei, E., Asante, E. A., Forkouh, S. K., Aboagye, M., & Antwi, C. O. (2019). Unemployment trends and labour market entry in Ghana: job search methods perspective. Labor History, 00(00), 1–18.

Affum-Osei, E., Mensah, H. K., Asante, E. A., & Forkuoh, S. K. (2021). Evaluating a job search strategy model of fit perceptions: a construct validation amongst unemployed job seekers. Career Development International.

Ali, A. A., Ryan, A. M., Lyons, B. J., Ehrhart, M. G., & Wessel, J. L. (2016). The long road to employment: incivility experienced by Job Seekers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(3), 333–349.

Allison, P. D. (2003). Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 545–557. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545

Amato, C., Baldner, C., & Pierro, A. (2016). “Moving” to a job. The role of locomotion in job search and (re)employment. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 62–69.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Baay, P. E., de Ridder, D. T. D., Eccles, J. S., van der Lippe, T., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2014). Self-control trumps work motivation in predicting job search behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3), 443–451.

Baldessarini, R. J., Innamorati, M., Erbuto, D., Serafini, G., Fiorillo, A., Amore, M., & Pompili, M. (2017). Differential associations of affective temperaments and diagnosis of major affective disorders with suicidal behavior. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210(December 2016), 19–21.

Baumeister, R. F., Heatherton, T. F., & Tice, D. M. (1994). Losing control: how and why people fail at self-regulation. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Baumeister, R. F., Tice, D. M., & Vohs, K. D. (2018). The strength model of self-regulation: Conclusions from the second decade of willpower research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 141–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617716946

Belle, M. A., Antwi, C. O., Ntim, S. Y., Affum-osei, E., & Ren, J. (2021). Am I Gonna Get a Job ? Graduating Students ’ Psychological Capital, Coping Styles, and Employment Anxiety.Journal of Career Development, (688),1–15.

Blau, G. (1994). Testing a Two-Dimensional Measure of Job Search Behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1994.1061

Boswell, W. R., Zimmerman, R. D., & Swider, B. W. (2012). Employee job search: toward an understanding of search context and search objectives. Journal of Management, 38(1), 129–163.

Brasher, E. E., & Chen, P. Y. (1999). Evaluation of success criteria in job search: a process perspective. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72, 57–70.

Cable, D. M., & DeRue, D. S. (2002). The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 875–884.

Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Klesh, J. (1983). Assessing the attitudes and perceptions of organizational members. In S. Seashore, E. Lawler, P. Mirvis, & C. Cammann (Eds.), Assessing organizational change: a guide to methods, measures, and practices (pp. 71–138). New York: John Wiley.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (2002). Control processes and self-organization as complementary principles underlying behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(4), 304–315.

Chadwick, I. C., & Raver, J. L. (2015). Motivating organizations to learn : Goal orientation and its influence on organizational learning. Journal of Management, 41(3), 957–986. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312443558

Colarelli, S. M. (1984). Methods of communication and mediating processes in realistic job previews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(4), 633–642.

Creed, P. A., & Hennessy, D. A. (2016). Evaluation of a goal orientation model of Vocational Identity. Career Development Quarterly, 64(4), 345–359.

Creed, P., King, V., Hood, M., & McKenzie, R. (2009). Goal orientation, self-regulation strategies, and job-seeking intensity in unemployed adults. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(3), 806–813.

Crossley, C. D., & Highhouse, S. (2005). Relation of job search and choice process with subsequent satisfaction. Journal of Economic Psychology, 26(2), 255–268.

da Veiga, M., S. P., & Turban, D. B. (2014). Who is searching for whom? Integrating recruitment and job search research. The Oxford Handbook of Job Loss and Job Search.

De-Ridder, D. T. D., Lensvelt-Mulders, G., Finkenauer, C., Stok, F. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2012). Taking stock of Self-Control: a Meta-analysis of how Trait Self-Control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(1), 76–99.

De Battisti, F., Gilardi, S., Guglielmetti, C., & Siletti, E. (2016). Perceived employability and reemployment: Do job search strategies and psychological distress matter?Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology.

DeShon, R. P., & Gillespie, J. Z. (2005). A motivated action theory account of goal orientation. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1096–1127.

Dineen, B. R., Vandewalle, D., Noe, R. A., Wu, L., & Lockhart, D. (2018). Who cares about demands–abilities fit? Moderating effects of goal orientation on recruitment and organizational entry outcomes. Personnel Psychology, 71(2), 201–224.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273.

Elliot, A. J., & Church, M. (1997). A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(1), 218–232.

Elliot, A. J. (1999). Approach and Avoidance Motivation and Achievement Goals. Educational Psychologist, 34(3), 169–189.

Elliot, A. J., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (1996). Approach and avoidance achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: A mediational analysis.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2002). Approach-avoidance motivation in personality: approach and avoidance temperaments and goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(5), 804–818.

Emirza, S., Öztürk, E. B., & Şengönül, A. S. (2021). The quality of international mobility experiences, general self-efficacy and job search self-efficacy: a time-lagged investigation. Current Psychology, 40(4), 1580–1591.

Fisher, S. L., & Ford, J. K. (1998). Differential Effects of Learner effort and goal orientation on two learning outcomes. Personnel Psychology, 51(2), 397–420.

Guan, Y., Deng, H., Sun, J., Wang, Y., Cai, Z., Ye, L., & Li, Y. (2013). Career adaptability, job search self-efficacy and outcomes: a three-wave investigation among chinese university graduates. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 561–570.

Hagger, M. S., Zhang, C. Q., Kangro, E. M., Ries, F., Wang, J. C. K., Heritage, B., & Chan, D. K. C. (2018). Trait self-control and self-discipline: structure, validity, and invariance across national groups. Current Psychology, 40(3), 1015–1030.

Hau, K. T., & Marsh, H. (2004). The use of item parcels in structural equation modeling: non-normal data and small sample sizes. British Journal of Mathematical Statistical Psychology, 757, 327–351.

Holding, A., Hope, N., Verner-Filion, J., & Koestner, R. (2019). In good time: A longitudinal investigation of trait self-control in determining changes in motivation quality. Personality and Individual Differences, 139(October 2018), 132–137.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Kanar, A. (2017). Employment goal commitment moderates impact of job search goal orientation on the job search process: a resource-allocation perspective. Career Development International, 22(6), 659–682.

Kanfer, R., Frese, M., Johnson, R. E., Kanfer, R., Frese, M., & Johnson, R. E. (2017). Motivation Related to Work: A Century of Progress Motivation Related to Work : A Century of Progress, 102(May), 338–355.

Kanfer, R., Wanberg, C. R., & Kantrowitz, T. M. (2001). Job search and employment: a personality-motivational analysis and Meta-analysis review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 837–855.

Koen, J., Klehe, U. C., Van Vianen, A. E. M., Zikic, J., & Nauta, A. (2010). Job-search strategies and reemployment quality. The impact of career adaptability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(1), 126–139.

Koen, J., van Vianen, A. E. M., van Hooft, E. A. J., & Klehe, U. C. (2016). How experienced autonomy can improve job seekers’ motivation, job search, and chance of finding reemployment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 95–96, 31–44.

Konstam, V., Tomek, S., Celen-Demirtas, S., & Sweeney, K. (2015). Volunteering and reemployment status in Unemployed emerging adults: a time-worthy investment? Journal of Career Assessment, 23(1), 152–165.

Kozlowski, S. W. J., Gully, S. M., Brown, K. G., Salas, E., Smith, E. M., & Nason, E. R. (2001). Effects of training goals and goal orientation traits on multidimensional training outcomes and performance adaptability. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 85(1), 1–31.

Kreemers, L. M., van Hooft, E. A. J., & van Vianen, A. E. M. (2021). If you want a job, don’t just search hard, search systematically: a field study with career starters. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 00(00), 1–14.

Lim, V. K. G., Chen, D., Aw, S. S. Y., & Tan, M. Z. (2016). Unemployed and exhausted? Job-search fatigue and reemployment quality. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 68–78.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: exploring the question, weighting the merits. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 151–173.

Massar, K., Bělostíková, P., & Sui, X. (2020). It’s the thought that counts: Trait self-control is positively associated with well-being and coping via thought control ability.Current Psychology,2372–2381.

Mathieu, J. E., Tannenbaum, S. I., & Salas, E. (1992). Influences of individual and situational characteristics on measures of training effectiveness. The Academy of Management Journal, 35(4), 828–847.

McFarland, L. A., Reeves, S., Porr, W. B., & Ployhart, R. E. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on job search behavior: an event transition perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(11), 1207–1217.

Miron-Spektor, E., Vashdi, D. R., & Gopher, H. (2021). Bright sparks and enquiring minds: Differential Effects of goal orientation on the Creativity Trajectory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(2), 310–318.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2015). Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Nakai, Y., Hill, S. C., Snell, A. F., & Ferrell, J. Z. (2018). A Job Club for older job seekers: change in attitude and Perceived Utility during Training. Journal of Career Development, 45(6), 551–565.

Noordzij, G., Van Hooft, E. A. J., Van Mierlo, H., Van Dam, A., & Born, M. P. (2013). The Effects of a learning-goal orientation training on Self-Regulation: a Field Experiment among Unemployed Job Seekers. Personnel Psychology, 66(3), 723–755.

Nyarko, C. O., Baah-Boateng, W., & Nketiah-Amponsah, E. (2014). Determinants of job search intensity in Ghana. Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 8(2), 193–211.

Okay-Somerville, B., & Scholarios, D. (2022). Focused for some, exploratory for others: job search strategies and successful University-to-work transitions in the context of Labor Market Ambiguity. Journal of Career Development, 49(1), 126–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/08948453211016058

Payne, S. C., Youngcourt, S. S., & Beaubien, J. M. (2007). A meta-analytic examination of the goal orientation nomological net. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 128–150.

Pituch, K. A., & Stevens, J. P. (2016). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (6th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Pompili, M., Serafini, G., Innamorati, M., Montebovi, F., Palermo, M., Campi, S., & Girardi, P. (2012). Car accidents as a method of suicide: a comprehensive overview. Forensic Science International, 223(1–3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.04.012.

Porath, C. L., & Bateman, T. S. (2006). Self-regulation: from goal orientation to job performance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 185–192.

Priyadarshini, C., Banerjee, P., & Chhetri, P. (2021). Identifying dimensions of job search strategy: a validation of measurement scale. Current Psychology, 40(2), 655–664.

Rawsthorne, L. J., & Elliot, J. (1999). Achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: a meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology Inc, 3(4), 326–344.

Saks, A. M. (2005). Job search success: a review and integration of the Predictors, Behaviors, and outcomes. Career development and counseling: putting theory and research to work (pp. 42–70). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. S. D. Brown.

Saks, A. M. (2006). Multiple predictors and criteria of job search success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(3), 400–415.

Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (2002). Is job search related to employment quality? It all depends on the fit. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 646–654.

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2010). Ensuring positiveness of the Scale Difference Chi-square test statistic. Psychometrika, 75(2), 243–248.

Smart, K. L., & DiMaria, J. (2018). Using storytelling as a job-search strategy. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 81(2), 185–198.

Stevenor, B. A., & Zickar, M. J. (2022). The development and validation of an updated job search behavior scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 135(April), 103722.

Stevens, C. K., & Beach, L. R. (1996). Job search and job selection. In L. R. Beach (Ed.), Decision making in the workplace: a unified perspective (pp. 33–47). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Stevens, C. K., & Turban, D. B. (2001). Impact of job seekers’ search strategies and tactics on search success. In Paper presented at the Annual conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Chicago, IL.

Swider, B. W., Zimmerman, R. D., & Barrick, M. R. (2015). Searching for the right fit: development of applicant person-organization fit perceptions during the recruitment process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 880–893.

Taggar, S., & Kuron, L. K. J. (2016). The toll of perceived injustice on job search self-efficacy and behavior. Career Development International, 21(3), 279–298.

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324.

Turban, D. B., Lee, F. K., Veiga, S. P. M., Haggard, D. L., & Wu, S. Y. (2013). Be happy, don’t wait: the role of Trait Affect in Job Search. Personnel Psychology, 66(2), 483–514.

van Hooft, E. A. J. (2014). Self-regulatory perspectives in the theory of planned job search behavior: Deliberate and automatic self-regulation strategies to facilitate job seeking.The Oxford Handbook of Job Loss and Job Search, (November),205–221.

van Hooft, E. A. J., Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Wanberg, C. R., Kanfer, R., & Basbug, G. (2021). Job search and employment success: A quantitative review and future research agenda. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(5), 674–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000675

Van Hooft, E. A. J., & Kreemers, L. M. (2021). Stop and start control at work : Differential validity of two types of self ‐ control for work behavior and emotion regulation. International Journal of Selection & Assessment, (June), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12359

Van Hooft, E. A. J., Wanberg, C. R., & van Hoye, G. (2013). Moving beyond job search quantity: towards a conceptualization and self-regulatory framework of job search quality. Organizational Psychology Review, 3(1), 3–40.

van Hooft, E. a J., & Noordzij, G. (2009). The effects of goal orientation on job search and reemployment: a field experiment among unemployed job seekers. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1581–1590.

Van Hoye, G. (2018). Job-search behavior as a multidimensional construct: A review of different job-search behaviors and sources. In The Oxford Handbook of Job Loss and Job Search (pp. 259–274).

Van Hoye, G., & Saks, A. M. (2008). Job search as goal-directed behavior: objectives and methods. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(3), 358–367.

Van Hoye, G., van Hooft, E. A. J., & Lievens, F. (2009). Networking as a job search behaviour: a social network perspective. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 82, 661–682. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X36067S

Vandewalle, D. (1997). Development and validation of a work domain goal orientation instrument. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 57(6), 995–1015.

VandeWalle, D., & Cummings, L. L. (1997). A test of the influence of goal orientation on the feedback-seeking process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(3), 390–400.

Vandewalle, D., Nerstad, C. G. L., & Dysvik, A. (2019). Goal orientation: a review of the Miles traveled and the Miles to go. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6, 115–144.

Vansteenkiste, S., Verbruggen, M., & Sels, L. (2016). Flexible job search behaviour among unemployed jobseekers: antecedents and outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 32(0), 1–21.

Virick, M., & McKee-Ryan, F. M. (2018). Reemployment quality, underemployment, and career outcomes. In The Oxford Handbook of Job Loss and Job Search (pp. 359–379).

Wanberg, C. R., Kanfer, R., & Rotundo, M. (1999). Unemployed individuals: motives, job-search competencies, and job-search constraints as predictors of job seeking and reemployment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(6), 897–910.

Wanberg, C. R. (2012). The individual experience of unemployment. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 369–396. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100500

Wang, L., & Yan, F. (2018). Emotion regulation strategy mediates the relationship between goal orientation and job search behavior among university seniors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 108(31100757), 1–12.

World Bank (2016). Expanding Job Opportunities in Ghana. Directions in Development by Honorati, Maddalena Sara Johansson, Silva de for the World Bank. Washington, DC

World Bank (2018). Third Ghana Economic Update: agriculture as an engine of growth and jobs creation. Washington, DC

Yamkovenko, B., & Hatala, J. P. (2014). Feedback-seeking and Social networking Behaviors during Job Search: a conceptual model. Human Resource Development Review, 13(1), 102–124.

Yeo, G. B., & Neal, A. (2004). A Multilevel Analysis of Effort, Practice, and Performance : Effects of Ability, Conscientiousness, and Goal Orientation, 89(2), 231–247.

Zimmerman, R. D., Boswell, W. R., Shipp, J., Dunford, B. B., & Boudreau, J. W. (2012). Explaining the Pathways between Approach-Avoidance personality traits and employees’ job search behavior. Journal of Management, 38(5), 1450–1475.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by a thesis support grant provided to the first author as part of a fully funded Hong Kong Ph.D.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Statement and Informed consent

In line with the declaration of Helsinki, informed consent was included on the first page of the research questionnaire. Participants were assured that the survey is strictly for academic work and that their responses will remain strictly confidential, anonymous and will be used only for the purpose of this research work. Participants provided their signature or initials on these forms to indicate that their participation in our project is voluntary and may withdraw from participating at any time. The study’s protocol was approved by the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee (SBREC) of The Chinese University of Hong Kong. February 17, 2023.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note