Abstract

Most studies that have compared sexual attitudes between men and women have focused on heterosexual individuals or have not controlled for sexual orientation. In addition, many have used measures of general sexual attitudes, which have more difficulty in predicting sexual behaviors and sexual health than measures of attitudes toward specific sexual behaviors. Therefore, the present study aimed to analyze whether gender and sexual orientation are related to attitudes toward specific sexual behaviors in Spain. The study sample consisted of 1725 participants (55.8% women) aged between 18 and 35 years and of different sexual orientations. All participants completed an instrument to measure attitudes toward specific contextualized sexual behaviors. After controlling for age and current relationship status, the results reveal that while women have more positive attitudes toward solitary sexual behaviors and erotic material than men, men have more positive attitudes toward unconventional and online sexual behaviors than women. Bisexual people have more positive attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with casual partners than homosexual people. Finally, bisexual and homosexual people have more positive attitudes towards solitary sexual behaviors and erotic material, unconventional sexual behaviors, and online sexual behaviors than heterosexuals. It is concluded that gender and sexual orientation are related to attitudes toward different types of sexual behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Attitude can be defined as a psychological tendency expressed by evaluating an entity or attitudinal object as being favorable or unfavorable to a certain degree (Eagly & Chaiken, 2007). Numerous studies have evaluated sexual attitudes, using different concepts such as sexual permissiveness, sexual conservatism-liberalism, and erotophobia-erotophilia (Blanc & Rojas, 2017). The main reason sexual attitudes have received so much attention is their relationship with sexual health (e.g., Carvalho et al., 2013; Sanders et al., 2006; Sierra et al., 2021) and sexual activity (e.g., Blanc et al., 2018b; Lemer et al., 2013). On the one hand, people with positive attitudes toward sexuality tend to report better sexual functioning (e.g., Carvalho et al., 2013; Sierra et al., 2021) and are more likely to use condom (Sanders et al., 2006) than people with negative attitudes toward sexuality. On the other hand, people with positive attitudes toward sexuality engage in a greater variety of sexual behaviors (Blanc, 2021; Blanc et al., 2018b) and more frequently (Lemer et al., 2013) than people with negative attitudes toward sexuality. These studies have included people from the general population (Sierra et al., 2021), young adults (Blanc, 2021; Lemer et al., 2013), and people with sexual dysfunction (Carvalho et al., 2013). The study of sexual attitudes in young adults is of special relevance because they are the most sexually active (Liu et al., 2015).

Because of the role of the social and cultural context in sexuality—specifically in sexual attitudes—numerous studies have compared sexual attitudes between men and women (Oliver & Hyde, 1993; Petersen & Hyde, 2011). While some studies have found no differences in sexual attitudes (e.g., Dosch et al., 2016; García-Vega et al., 2017; Lawal, 2010; Wolf, 2012), others have found that men have more permissive/liberal/erotophilic sexual attitudes than women (e.g., Ojedokun & Balogun, 2008; Ojo, 2014; Scandurra et al., 2022; Sprecher, 2013; Swami et al., 2017; Zuo et al., 2012).

Theories that have attempted to explain the differences in sexuality between men and women include evolutionary theory (Buss, 1998), social structure theory (Eagly & Wood, 1999), and the cognitive theory of social learning (Bussey & Bandura, 1999). Evolutionary theory suggests that women and men use different strategies to maximize the number of genes they pass on (Buss, 1998). A prominent interpretation of this theory—as applied to sexuality—is the sexual strategy theory (Petersen & Hyde, 2010). This theory holds that because women possess a time limit to bearing and caring for children, they focus on ensuring their children’s survival by selectively choosing mates who will provide resources for their families. However, because men have an unlimited reproductive capacity, they desire a higher number of sexual partners to maximize the likelihood of transmitting their genes (Buss, 1998). Social structure theory (Eagly & Wood, 1999) holds that sexuality differences between men and women are due to power inequalities, expecting that there will be fewer differences in the sexual behaviors of men and women in more egalitarian societies (Petersen & Hyde, 2010). On the other hand, the cognitive theory of social learning (Bussey & Bandura, 1999) suggests that these differences exist because, in certain societies, people observe different behaviors associated with each gender. As a result, they are reinforced or punished when they engage in certain behaviors. Generally, men have been reinforced for seeking and engaging in sexual activity, while for women such activities are restricted to relationships based on love and commitment (Sprecher et al., 1997). These theories could explain the different reasons men and women have sex, as reported in some studies (e.g., Mavrikiou et al., 2017). While women have more emotional reasons for having sex, claiming to be in love on their first sexual encounter, men seek more physical pleasure.

Most studies that have analyzed differences between men and women in sexual attitudes have focused on heterosexual individuals (e.g., Dosch et al., 2016; Sierra et al., 2021) or have not controlled for sexual orientation (e.g., Ojo, 2014; Shah et al., 2020). Recent studies conducted in United States (Lentz & Zaikman, 2021; Leri & DelPriore, 2021) and Portugal (Silva et al., 2021) examining the effect of sexual orientation on sexual attitudes in women from the general population and young adults show that non-heterosexual women have more permissive sexual attitudes than heterosexual women. However, in Italy Scandurra et al. (2022) explored the link between sexual orientation and sexual attitudes in men and women aged over 50 years and found no statistically significant relationship. In contrast, other studies in United States (Grollman, 2017; Nurius, 1983) and England (Swami et al., 2017) with both men and women samples found that non-heterosexuals have more liberal/erotophilic sexual attitudes than heterosexuals.

Various hypotheses have also been proposed to explain differences in sexual attitudes according to sexual orientation, mating costs, mating opportunities, and differential psychosocial stress (Leri & DelPriore, 2021). According to the differential mating costs hypothesis, homosexual women should have more permissive sexual attitudes than heterosexual women because their potential biological costs are lower. The sexual attitudes of bisexual women should be more permissive than those of heterosexual women and less of homosexual women because some of their encounters are with men (high cost) and others with women (low cost). According to the differential mating opportunities hypothesis, homosexual women should have more permissive sexual attitudes because they have fewer mating opportunities. The sexual attitudes of heterosexual women should be more permissive than those of bisexual women and less permissive than homosexual women. Finally, according to the differential psychosocial stress hypothesis, non-heterosexual women should have more permissive sexual attitudes than heterosexual women because they experience more psychosocial stress (because of their sexual orientation) due to problems such as harassment, discrimination, and violence (Hatzenbuehler, 2009).

Much of the research related to the relationship between gender, sexual orientation and sexual attitudes has focused on measures of general sexual attitudes, such as the Sexual Opinion Survey that measures the erotophobia-erotophilia construct (e.g., García-Vega et al., 2017; Swami et al., 2017). However, if we measure attitudes with the goal of predicting behaviors, a measure focused on attitudes toward specific contextualized sexual behaviors is more appropriate than one of sexual attitudes in general (Blanc et al., 2018b). It has been shown that the relationship between attitude and behavior is stronger when the measures are matched in terms of object, context, and time (Glasman & Albarracín, 2006; Kraus, 1995). In addition, in a recent study in Spain, Sierra et al. (2021) found that a measure of attitudes toward a specific behavior has a stronger relationship with sexual health than a measure of general sexual attitudes, such as the Sexual Opinion Survey.

Studies in the literature have reported in young adults that gender and sexual orientation are related to measures of attitudes toward sex in different contexts, such as casual sex. For example, in United States men have been found to have more favorable attitudes toward casual sex than women (England & Bearak, 2014), and women with a non-exclusively heterosexual orientation have more positive attitudes than women with an exclusively heterosexual orientation (Zhana & Ritch, 2010). Along these lines, Currin et al. (2016), in a study of people from the general population who identified with a heterosexual orientation, found that those attracted to people of the same sex were more open to casual sex than those who indicated a lack of attraction to people of the same sex. Consistent with these studies, in Hungary Keresztes et al. (2020) conducted a cluster analysis and found in young adults that the “Conservative” group (with more conservative attitudes toward casual sex) included more women and heterosexual individuals.

On the other hand, some studies conducted in different countries (United States, Canada, China, Spain, and Norway) and age groups (adolescent, young, adult young, and general population) have explored the link between gender and/or sexual orientation and measures of attitudes toward more specific sexual behaviors. For example, while some studies have found no relationship between gender and attitude toward masturbation (e.g., Driemeyer et al., 2017), others have found that men have more positive attitudes than women (e.g., Wang et al., 2007). Homosexual people have also been found to have more positive attitudes toward masturbation than heterosexual people (Cowden & Koch, 1995). Similarly, previous studies have shown that men have more positive attitudes toward sexual fantasies (Sierra et al., 2020, 2021), pornography use (Træen et al., 2004), engaging in threesomes (Thompson & Byers, 2017; Thompson et al., 2021), and online sexual behaviors (Byers & Shaughnessy, 2014; Samimi & Alderson, 2014) than women. Likewise, non-heterosexuals have been found to have more positive attitudes toward threesomes (Thompson et al., 2021) and various types of online sexual activities (Byers & Shaughnessy, 2014) than heterosexuals.

Although some studies relate gender and/or sexual orientation to measures of attitudes toward sex in different contexts (e.g., casual sex) or to measures of attitudes toward more specific sexual behaviors (e.g., masturbation), relatively few have studied the relationship between these variables and measures of attitudes toward specific sexual behaviors in different contexts. One exception is the development of the Attitudes Toward Sexual Behaviors Scale (Blanc et al., 2020). The Attitudes Toward Sexual Behaviors Scale was developed in Spain (Blanc et al., 2018b) but was adapted to English and applied in other countries such as Canada (Blanc et al., 2018a) and the United States (Blanc & Rojas, 2020). This scale measures attitudes toward specific sexual behaviors in different contexts, including frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a steady partner, frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a casual partner, solitary sexual behaviors (when a person has a partner and does not have a partner), use of erotic material, unconventional sexual behaviors, and online sexual behaviors (Blanc et al., 2020). In addition, it has a greater capacity to predict sexual behaviors than the Sexual Opinion Survey (Blanc et al., 2018b). Studies that have investigated the relationship between scores on this scale and gender have found that the overall scale scores are higher in men than women (Blanc, 2021; Blanc & Rojas, 2020; Blanc et al., 2018b). However, most studies have focused on heterosexual individuals and have not differentiated between the various subscales (types of sexual behavior).

Objective and hypothesis

Given the above, the present study aimed to analyze whether gender and sexual orientation are related to attitudes towards specific contextualized sexual behaviors in Spain. The behaviors of interest are frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a steady partner, frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a casual partner, solitary sexual behaviors and the use of erotic material, unconventional sexual behaviors, and online sexual behaviors. According to previous studies, it is expected that:

Hypothesis 1

Women have more positive attitudes towards frequent dyadic sexual behavior with a stable partner than men (Mavrikiou et al., 2017).

Hypothesis 2

Men have more positive attitudes toward unconventional sexual behaviors (Thompson & Byers, 2017; Thompson et al., 2021) and online sexual behaviors (Byers & Shaughnessy, 2014; Samimi & Alderson, 2014) than women.

Hypothesis 3

Non-heterosexuals have more positive attitudes towards solitary sexual behaviors and the use of erotic material (Cowden & Koch, 1995), unconventional sexual behaviors (Thompson et al., 2021), and online sexual behaviors (Byers & Shaughnessy, 2014) than heterosexuals.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 1725 participants aged between 18 and 35 years (M = 22.83; SD = 3.65). 44% were men (n = 762), and 55.8% were women (n = 963). A total of 60.9% had completed vocational training or high school (n = 1050), 30.0% had completed university studies (n = 533), 7.2% had completed compulsory secondary education (n = 124), and 1.0% had no studies or had completed primary education (n = 18). At the time of the study, 49.4% had a steady partner (n = 853) and 50.6% did not have a steady partner (n = 872). In addition, 72.3% identified with a heterosexual orientation (n = 1248), 17.5% with a bisexual orientation (n = 302), and 10.1% with a homosexual orientation (n = 175).

Measures

Sociodemographic variables. Gender, age, educational level, current relationship status, and sexual orientation.

The scale of Attitudes toward Sexual Behaviors (Blanc et al., 2020). This instrument measures attitudes towards specific sexual behaviors in different contexts. It consists of 22 items and five subscales for attitudes toward sexual behaviors.

The subscales are attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a steady partner (4 items; e.g., caressing/touching any intimate part of the body of a steady partner), attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a casual partner (4 items; e.g., oral sex with a casual partner), attitudes toward solitary sexual behaviors and use of erotic material (6 items; e.g., watching erotic movies [for example, showing sexual activities]), attitudes toward unconventional sexual behaviors (4 items; e.g., sexual activity with a group of persons at the same time [orgy or group sex]), and attitudes toward online sexual behaviors (4 items; sex over the internet [cybersex] with a casual partner). The subscales have a Likert-type format with five response options from 1 (very negative) to 5 (very positive). The total score on the subscales is obtained by summing all the items and can range from 4 to 20, except for the 6-item subscale, which can range from 6 to 30. The higher the score, the more positive the attitudes towards sexual behaviors. The reliability estimated by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the different gender and sexual orientation groups and the total sample are shown in Table 1.

Procedure

The questionnaire was developed using Google Forms. The link to the questionnaire was disseminated through social networks. Specifically, the information about the study was disseminated to students from different universities in Spain so that they could spread it on their social networks. University students were encouraged to share the information and link to participate in the study through Instagram, Facebook, as well as WhatsApp. University students were given the information both in the classroom and via email. At the outset, we provided a description of the objective of the research, and emphasized that the data would be treated globally, with responses being completely anonymous. In addition, the risks derived from participation in the study were reported and an email address was included for any questions or information about the study. The participants were required to give their informed consent online before taking part in the study. The questionnaire took approximately 10 min to complete and the administration was conducted from November 2021 to March 2022. The study was approved by the bioethics committee of the Junta de Andalucía (registration code: 2391-N-21).

Data analysis

First, correlations between age and the different subscales were examined using Pearson´s Correlation Coefficient (r). In addition, the mean scores of the subscales according to current relationship status (with and without a steady partner) were compared using Student’s t statistic and the effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d. The descriptive statistics (M and SD) of the scores obtained on the different subscales according to gender and sexual orientation were also analyzed. Then, to test for statistically significant differences in attitudes towards sexual behaviors according to gender and sexual orientation, separate two-factor MANOVAs were conducted. For each MANOVA, a subscale was included as a dependent variable and gender and sexual orientation as independent variables. Moreover, age and current relationship status were included as a covariate in the analyses. The effect size was calculated using partial eta squared (η2p). When there was an effect of sexual orientation on the dependent variable, post-hoc analyses (multiple comparisons) were conducted using the Bonferroni statistic to test for differences between groups. When there was an interaction effect, simple effects analyses were carried out. All data analyses were conducted using the SPSS version 25 statistical software.

Results

The Table 2 shows the correlations between age and the different subscales. Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics (M and SD) of the scores for the five subscales according to current relationship status and comparison of the mean scores. The results show statistically significant differences in attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a steady partner, in attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a casual partner, and in attitudes toward online sexual behaviors. As shown in Table 3, people with steady partner have more positive attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a steady partner than people without steady partner. However, people without steady partner have more positive attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a casual partner and toward unconventional sexual behaviors than people with steady partner. Although the significant relationships found were small, the effect of current relationship status, and age were controlled by including them as covariates in the analyses.

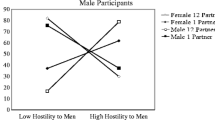

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics (M and SD) of the scores for the five subscales according to gender and sexual orientation. For the attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a steady partner, the results revealed an interaction between gender and sexual orientation (F(2,1717) = 3.855, p = .021, η2p = 0.004). Analyses of the simple effects revealed statistically significant differences only between homosexual women and homosexual men (p = .004). As shown in Table 4, homosexual women have more positive attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a steady partner than homosexual men.

For the attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a casual partner, the results revealed an effect of sexual orientation (F(2,1717) = 3.493, p = .031, η2p = 0.003). However, there was no gender effect (F(1,1717) = 0.528, p = .468) and no interaction between these two variables (F(2,1717) = 2.439, p = .088). Multiple a posteriori comparisons revealed differences between homosexual and bisexual individuals (p = .048). As shown in Table 4, bisexuals have more positive attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a casual partner than homosexuals. However, there are no differences in attitudes toward these behaviors between heterosexuals and homosexuals (p > .999) or between heterosexuals and bisexuals (p = .057).

For the attitudes toward solitary sexual behaviors and use of erotic material, the results show an effect of gender (F(1,1717) = 5.438, p = .030, η2p = 0.003) and sexual orientation (F(2,1717) = 11.723, p < .001, η2p = 0.013), but no significant interaction between these variables (F(2,1717) = 0.656, p = .519). Table 4 shows that women have more positive attitudes toward solitary sexual behaviors and erotic material than men. Multiple a posteriori comparisons also revealed differences between heterosexuals and homosexuals (p < .001) and between heterosexuals and bisexuals (p = .005). Homosexuals and bisexuals have more positive attitudes toward solitary sexual behaviors and use of erotic material than heterosexuals. Finally, no differences in attitudes towards these behaviors were found between homosexuals and bisexuals (p > .999).

For the attitudes toward unconventional sexual behaviors, the results also show an effect of gender (F(1,1717) = 50.234, p < .001, η2p = 0.028) and sexual orientation (F(2,1717) = 24.839, p < .001, η2p = 0.028), with no interaction between these variables (F(2,1717) = 1.767, p = .171). Table 4 shows that men have more positive attitudes toward unconventional sexual behaviors than women. Multiple a posteriori comparisons also showed differences between heterosexuals and homosexuals (p < .001) and between heterosexuals and bisexuals (p < .001). Homosexuals and bisexuals have more positive attitudes toward unconventional sexual behaviors than heterosexuals, while no differences in attitudes were found between homosexuals and bisexuals (p > .999).

For the attitudes toward online sexual behaviors, the results indicate an effect of gender (F(1,1717) = 28.595, p < .001, η2p = 0.016) and sexual orientation (F(2,1717) = 22.582, p < .001, η2p = 0.026), with no interaction between these variables (F(2,1717) = 0.143, p = .867). Table 4 shows that men have more positive attitudes toward online sexual behaviors than women. Multiple a posteriori comparisons also show differences between heterosexuals and homosexuals (p < .001) and between heterosexuals and bisexuals (p < .001). Homosexuals and bisexuals have more positive attitudes toward unconventional sexual behaviors than heterosexuals. Finally, homosexuals and bisexuals did not differ in their attitudes toward these behaviors (p > .999).

Discussion

Most studies concerned with the relationship between gender and sexual attitudes have focused on people with a heterosexual orientation (e.g., Dosch et al., 2016; Sierra et al., 2021) or have not controlled for sexual orientation (e.g., Ojo, 2014; Shah et al., 2020). In addition, many have used measures of general sexual attitudes (e.g., García-Vega et al., 2017; Swami et al., 2017), which have more difficulty in predicting sexual behaviors (Blanc et al., 2018b) and sexual health (Sierra et al., 2021) than measures of attitudes toward specific sexual behaviors. While recent studies (Blanc, 2021; Blanc & Rojas, 2020; Blanc et al., 2018b) have examined the association between gender and scores obtained on a measure of attitudes toward specific contextualized sexual behaviors, these studies have focused on heterosexual individuals and did not distinguish between different types of sexual behaviors. Therefore, the present study aimed to analyze whether gender and sexual orientation are related to attitudes toward specific contextualized sexual behaviors in Spain. These behaviors were frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a steady partner, frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a casual partner, solitary sexual behaviors and use of erotic material, unconventional sexual behaviors, and online sexual behaviors.

First, as expected (Hypothesis 1), and in accord with other studies (Mavrikiou et al., 2017), homosexual women have more positive attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a steady partner than homosexual men. This result is consistent with theories that attempt to explain the differences between men and women sexuality (e.g., cognitive theory) and with the results of studies showing the different reasons why women have sex (e.g., Mavrikiou et al., 2017). Women have been reinforced for limiting sexual activity to relationships based on love and commitment (Sprecher et al., 1997) and, therefore, may value sexual behaviors with stable partners more positively than men. In addition, women have more emotional reasons for having sex than men (Mavrikiou et al., 2017), and emotions such as love are stronger in stable relationships than in casual relationships. This result also supports the notion that women more frequently engage in romantic behaviors than men (García-Vega et al., 2005). However, contrary to our expectations (Hypothesis 1), no differences were found between heterosexual and bisexual women and men in attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a steady partner. Nor were differences found between women and men in attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a casual partner. These results indicate that, in general, there are no differences between men and women in attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a partner (e.g., fondling, vaginal intercourse, or oral sex).

Regarding attitudes toward solitary sexual behaviors (masturbation and sexual fantasies) and use of erotic material, it has been found that women have more positive attitudes than men. These results are inconsistent with those reported in other studies where no differences in attitudes toward masturbation were found between men and women (Abramson et al., 1981; Driemeyer et al., 2017; Kelley et al., 1997; Sümer, 2013) or in those studies where men were found to have more positive attitudes towards masturbation (Sümer, 2015; Wang et al., 2007), sexual fantasies (Santos-Iglesias et al., 2013; Sierra et al., 2021), or pornography use (Træen et al., 2004) than women.

On the other hand, as expected (Hypothesis 2), and in line with other studies (Byers & Shaughnessy, 2014; Samimi & Alderson, 2014; Thompson & Byers, 2017; Thompson et al., 2021), men have more positive attitudes toward unconventional sexual behaviors such as threesomes and group sex and online sexual behaviors such as sexting and cybersex than women. These results are also compatible with theories that attempt to explain the differences between men and women (e.g., evolutionary theory) and the results of studies showing the different reasons men have sex (e.g., Mavrikiou et al., 2017). The reproductive capacity of men is not limited (Buss, 1998), and men have been reinforced for seeking and engaging in sexual activity (Sprecher et al., 1997). Therefore, they may value more positively unconventional sexual behaviors such as threesomes or group sex.

Online sexual behaviors, such as cybersex, are also an easy and quick way to have a lot of sex. For this reason, men may have rated such behaviors more positively than women. Previous studies have also found that men have more positive attitudes toward a partnered-arousal online sexual activity (Byers & Shaughnessy, 2014) or, more specifically, more positive attitudes toward sexting (Samimi & Alderson, 2014) than women. These results could explain why men have more sexual partners and engage in more online sexual behaviors than women (Shaughnessy et al., 2011) and are also consistent with the observation that men engage in more cybersex with strangers compared with women (Shaughnessy & Byers, 2014).

Concerning attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a casual partner, it has been found that bisexual people have more positive attitudes than homosexuals. These results are consistent with those found in other studies where bisexual women have more sexual partners than homosexual (Jankowiak & Escasa-Dorne, 2016). However, unlike other studies (e.g., Leri & DelPriore, 2021), no differences were found between homosexuals and heterosexuals or between bisexuals and heterosexuals. The discrepancies between these findings and those of other studies could be due to the measures employed.

On the other hand, as expected (Hypothesis 3) and in accord with other studies (Byers & Shaughnessy, 2014; Cowden & Koch, 1995; Thompson et al., 2021), non-heterosexuals—both homosexuals and bisexuals—have more positive attitudes toward solitary sexual behaviors, erotic material, and non-conventional and online sexual activities than heterosexuals. These results are consistent with the differential psychosocial stress hypothesis, which proposes that non-heterosexual women should have more permissive sexual attitudes than their heterosexual counterparts because they experience more psychosocial stress (Leri & DelPriore, 2021). The findings are also consistent with homosexuals having more positive attitudes toward masturbation (Cowden & Koch, 1995) and non-heterosexuals having more positive attitudes toward threesomes (Thompson et al., 2021) than heterosexuals. Furthermore, these results are in line with the observations of Byers and Shaughnessy (2014), who reported that non-heterosexual people had more positive attitudes toward various types of online sexual activities than heterosexual people. These results might also explain why non-heterosexual people engage in more threesome (Thompson et al., 2021) and online sexual behaviors such as sexting (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2017) than heterosexual people. In particular, non-heterosexual people may value online sexual behaviors more positively because they have more difficulty expressing their sexuality, and the Internet provides an avenue for interacting with others without fear of negative social consequences, such as rejection (Brown et al., 2005). In addition, the number of potential sexual partners for homosexual people is also more limited and they experience more difficulties finding a partner, and online sexual activity offers the possibility of accessing sex quickly.

The results of the current study cannot be compared with those of previous studies using the scale of attitudes toward sexual behaviors (Blanc, 2021; Blanc & Rojas, 2020; Blanc et al., 2018b). This is because those focused on the total scale score (they have not differentiated between the subscale scores) and all or the most of the participants were heterosexual.

Limitations

The current study has certain limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results. The first limitation to note is that participants needed to have social networks and have email address to access the online questionnaire. This could have led to a sampling bias, since not all people have these resources and access to internet. Another limitation is that the sample was not randomly selected. Both limitations mean that the generalization of some of the results obtained should be made with some caution. The type of research carried out (quantitative), where software is used to analyze the data globally and statistically, has also some limitations. For example, it does not allow for an individual understanding of why people have these attitudes toward sexual behaviors. Therefore, in future studies it would be highly relevant to carry out qualitative studies to understand the attitudes of people toward sexual behaviors. In this type of studies, where the required sample is smaller, people who identify with other genders (e.g., fluid gender) and other sexual orientations (e.g., pansexuality or asexuality) could be included.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations, this study shows that both gender and sexual orientation are related to attitudes toward different types of sexual behaviors. On the one hand, gender is related to attitudes towards frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with a stable partner (in homosexuals), solitary sexual behaviors and erotic material, unconventional sexual behaviors, and online sexual behaviors. While homosexual women value frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with steady partners more positively than homosexual men and women generally value solitary sexual behaviors and erotic material more positively than men, men rate unconventional sexual behaviors and online sexual behaviors more positively than women.

Sexual orientation is also related to attitudes toward frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with casual partners, solitary sexual behaviors and erotic material, unconventional sexual behaviors, and online sexual behaviors. Bisexual people rate frequent dyadic sexual behaviors with casual partners more positively than homosexual persons. Finally, non-heterosexuals (both homosexuals and bisexuals) rate solitary sexual behaviors and erotic material, unconventional sexual behaviors, and online sexual activities more positively than heterosexuals.

These results suggest that while women show favorable attitudes towards certain sexual behaviors, men have more positive attitudes to other behaviors. The results also show that, in general, non-heterosexuals have positive attitudes toward a greater number of sexual behaviors than heterosexuals. The results of the present study could be useful for predicting specific sexual behaviors in people of different genders and sexual orientations, and for the design of sexual prevention and intervention programs. According to the results of this study, it would be expected that women engage in more solitary sexual behaviors than men, while men engage in more unconventional and online sexual behaviors than women. Furthermore, it would be expected that non-heterosexual people engage in more solitary, unconventional, and online sexual behaviors than heterosexual people. Finally, in the same way that has been examined in previous studies with heterosexual people (e.g., Sierra et al., 2021), in future studies it will be important to explore the relationship between attitudes toward sexual behaviors and sexual functioning among sexual minority.

Data Availability

The database is available at https://osf.io/zxb4p.

References

Abramson, P. R., Perry, L. B., Rothblatt, A., Seeley, T. T., & Seeley, D. M. (1981). Negative attitudes toward masturbation and pelvic vasocongestion: a thermographic analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 15, 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(81)90046-5

Blanc, A. (2021). El papel mediador de las actitudes entre los comportamientos sexuales de hombres y mujeres. Revista Internacional de Andrología, 19, 107–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.androl.2019.11.002

Blanc, A., Byers, S. E., & Rojas, A. J. (2018a). Evidence for the validity of the attitudes toward sexual behaviours scale (ASBS) with Canadian young people. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 27, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2017-0024

Blanc, A., Byers, S. E., & Rojas, A. J. (2020). Attitudes toward Sexual Behaviors Scale. In R. R. Milhasuen, J. D. Sakaluk, C. M. Davis & W. L. Yarber (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (4th ed., pp. 423–426). New York: Routledge.

Blanc, A., & Rojas, A. J. (2017). Instrumentos de medida de actitudes hacia la sexualidad: una revisión bibliográfica sistemática. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación – e Avaliação Psicológica, 1, 17–32. https://doi.org/10.21865/RIDEP43_17

Blanc, A., & Rojas, A. J. (2020). Attitudes toward sexual behaviours in different ethnocultural groups and their relationship with the acculturation process. Ceskoslovenska Psychologie, 3, 342–359.

Blanc, A., Sayans-Jiménez, P., Ordóñez-Carrasco, J. L., & Rojas, A. J. (2018b). Comparison of the predictive capacity of the erotophobia-erotophilia and the attitudes toward sexual behaviors in the sexual experience of young adults. Psychological Reports, 121, 815–830. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117741141

Brown, G., Maycock, B., & Burns, S. (2005). Your picture is your bait: use and meaning of cyberspace among gay men. Journal of Sex Research, 42, 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490509552258

Buss, D. M. (1998). Sexual strategies theory: historical origins and current status. Journal of Sex Research, 35, 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499809551914

Bussey, K., & Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review, 106, 676–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.676

Byers, E. S., & Shaughnessy, K. (2014). Attitudes toward online sexual activities. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 8. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2014-1-10

Carvalho, J., Veríssimo, A., & Nobre, P. J. (2013). Cognitive and emotional determinants characterizing women with persistent genital arousal disorder. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10, 1549–1558. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12122

Cowden, C. R., & Koch, P. B. (1995). Attitudes related to sexual concerns: gender and orientation comparisons. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 21, 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01614576.1995.11074139

Currin, J. M., Hubach, R., Brown, D., C., & Farley, S. (2016). Impact of non-heterosexual impulses on heterosexuals’ attitudes towards monogamy and casual sex. Psychology & Sexuality, 7, 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2016.1168313

Dosch, A., Belayachi, S., & Van der Linden, M. (2016). Implicit and explicit sexual attitudes: how are they related to sexual desire and sexual satisfaction in men and women? The Journal of Sex Research, 53, 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.1003361

Driemeyer, W., Janssen, E., Wiltfang, J., & Elmerstig, E. (2017). Masturbation experiences of swedish senior high school students: gender differences and similarities. The Journal of Sex Research, 54, 631–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1167814

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (2007). The advantages of an inclusive definition of attitude. Social Cognition, 25, 582–602. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2007.25.5.582

Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (1999). The origins of sex differences in human behavior: Evolved dispositions versus social roles. American Psychologist, 54, 408–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.6.408

England, P., & Bearak, J. (2014). The sexual double standard and gender differences in attitudes toward casual sex among U.S. university students. Demographic Research, 30, 1327–1338. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2014.30.46

Gámez-Guadix, M., Santisteban, P., & Resett, S. (2017). Sexting among Spanish adolescents: prevalence and personality profiles. Psicothema, 29, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.222

García-Vega, E., Fernández, P., & Rico, A. R. (2005). Género y sexo como variables moduladoras del comportamiento sexual en jóvenes universitarios. Psicothema, 17, 49–56.

García-Vega, E., Rico, R., & Fernández, R. (2017). Sex, gender roles and sexual attitudes in university students. Psicothema, 29, 178–183. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2015.338

Glasman, L. R., & Albarracín, D. (2006). Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: a meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 778–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.778

Grollman, E. A. (2017). Sexual orientation differences in attitudes about sexuality, race, and gender. Social Science Research, 61, 126–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.05.002

Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 707–730. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016441

Jankowiak, W., & Escasa-Dorne, M. (2016). Bisexual and straight females’ preferences voiced on an adult sex dating site. Current Anthropology, 57, 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1086/684644

Kelley, K., Byrne, D., Greendlinger, V., & Murnen, S. K. (1997). Content, sex of viewer, and dispositional variables as predictors of affective and evaluative responses to sexually explicit films. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 9, 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1300/j056v09n02_04

Keresztes, N., Pikoa, B. F., Howard-Paynebc, L., & Gupta, H. H. (2020). An exploratory study of Hungarian university students’ sexual attitudes and behaviours. International Journal of Emotional Education, 12, 83–87.

Kraus, S. J. (1995). Attitudes and the prediction of behavior: a meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Society for Personality and Social Psychology, 21, 58–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295211007

Lawal, A. M. (2010). Gender, religiosity and self-esteem as predictors of sexual attitudes of students in a nigerian tertiary institution. Gender and Behaviour, 8, 50–63. https://doi.org/10.4314/gab.v8i1.54680

Lemer, J. L., Blodgett-Salafia, E. H., & Benson, K. E. (2013). The relationship between college women’s sexual attitudes and sexual activity: the mediating role of body image. International Journal of Sexual Health, 25, 204–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2012.722593

Lentz, A. M., & Zaikman, Y. (2021). The big “O”: sociocultural influences on orgasm frequency and sexual satisfaction in women. Sexuality & Culture, 25, 1096–1123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09811-8

Leri, G., & DelPriore, D. L. (2021). Understanding variation in women’s sexual attitudes and behavior across sexual orientations: evaluating three hypotheses. Personality and Individual Differences, 173, 110629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110629

Liu, G., Hariri, S., Bradley, H., Gottlieb, S. L., Leichliter, J. S., & Markowitz, L. E. (2015). Trends and patterns of sexual behaviors among adolescents and adults aged 14 to 59 years, United States. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 42, 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000231

Mavrikiou, P. M., Parlalis, S. K., & Athanasiou, A. (2017). Gender differences in the sexual experiences, attitudes, and beliefs of Cypriot university-educated youth. Journal of Sexuality and Culture, 21, 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-016-9377-7

Nurius, P. S. (1983). Mental health implications of sexual orientation. Journal of Sex Research, 19, 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224498309551174

Ojedokun, A., & Balogun, S. (2008). Gender differences in premarital sexual permissiveness among university undergraduates. Gender and Behaviour, 6, 1651–1672. https://doi.org/10.4314/gab.v6i1.23411

Ojo, A. A. (2014). Age and gender differences in premarital sexual attitudes of young people in South-West Nigeria. Gender and Behaviour, 12, 6301–6311.

Oliver, M. B., & Hyde, J. S. (1993). Gender differences in sexuality: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.114.1.29

Petersen, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2010). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality: 1993 to 2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017504

Petersen, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2011). Gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors: a review of meta-analytic results and large datasets. The Journal of Sex Research, 48, 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.551851

Sanders, S. A., Graham, C. A., Yarber, W. L., Crosby, R. A., Dodge, B., & Milhausen, R. R. (2006). Women who put condoms on male partners: correlates of condom application. American Journal of Health Behavior, 30, 460–466. https://doi.org/10.5555/ajhb.2006.30.5.460

Santos-Iglesias, P., Sierra, J. C., & Vallejo-Medina, P. (2013). Predictors of sexual assertiveness: the role of sexual desire, arousal, attitudes, and partner abuse. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 1043–1052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9998-3

Samimi, P., & Alderson, K. G. (2014). Sexting among undergraduate students. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.027

Scandurra, C., Mezza, F., Esposito, C., Vitelli, R., Maldonato, N. M., Bochicchio, V., Chiodi, A., Giami, A., Valerio, P., & Amodeo, A. L. (2022). Online sexual activities Italian older adults: the role of gender, sexual orientation, and permissiveness. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19, 248–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00538-1

Shah, S., Patel, A. V., Patel, K., & Mehta, P. I. (2020). A prospective evaluation of a change in attitude towards sexuality in medical students after their three years in medical college. Archives of Psychiatry & Psychotherapy, 22, 62–71. https://doi.org/10.12740/APP/111728

Shaughnessy, K., & Byers, E. S. (2014). Contextualizing cybersex experience: heterosexually identified men and women’s desire for and experience with cybersex with three types of partners. Computers in Human Behaviour, 32, 178–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.005

Shaughnessy, K., Byers, E. S., & Walsh, L. (2011). Online sexual activity experience of heterosexual students: gender similarities and differences. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9629-9

Sierra, J. C., Arcos-Romero, A. I., & Calvillo, C. (2020). Validity evidence and norms of the Spanish version of the Hurlbert Index of Sexual Fantasy. Psicothema, 32, 429–436. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2020.14

Sierra, J. C., Gómez-Carranza, J., Álvarez-Muelas, A., & Cervilla, O. (2021). Association of sexual attitudes with sexual function: general vs. specific attitudes. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health, 18, 10390. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910390

Silva, J., Ferreira, S., Barros, V., Mourão, A., Corrêa, G., Caridade, S., Sousa, H. F. P. E., Dinis, M. A. P., & Leite, Â. (2021). Associations between cues of sexual desire and sexual attitudes in Portuguese women. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 11, 1292–1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040094

Sprecher, S. (2013). Attachment style and sexual permissiveness: the moderating role of gender. Personality and Individual Differences, 55, 428–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.005

Sprecher, S., Regan, P. C., McKinney, K., Maxwell, K., & Wazienski, R. (1997). Preferred level of sexual experience in a date or mate: the merger of two methodologies. The Journal of Sex Research, 34, 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499709551901

Sümer, Z. H. (2013). Effects of gender and sex-role orientation on sexual attitudes among Turkish university students. Social Behavior and Personality, 41, 995–1008. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2013.41.6.995

Sümer, Z. H. (2015). Gender, religiosity, sexual activity, sexual knowledge, and attitudes toward controversial aspects of sexuality. Journal of Religion and Health, 54, 2033–2044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9831-5

Swami, V., Weis, L., Barron, D., & Furnham, A. (2017). Associations between positive body image, sexual liberalism, and unconventional sexual practices in U.S. adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 2485–2494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0924-y

Thompson, A. E., & Byers, E. S. (2017). Heterosexual young adults’ interest, attitudes, and experiences related to mixed-gender, multi-person sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 813–822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0699-1

Thompson, A. E., Cipriano, A. E., Kirkeby, K. M., Wilder, D., & Lehmiller, J. J. (2021). Exploring variations in North American adults’ attitudes, interest, experience, and outcomes related to mixed-gender threesomes: a replication and extension. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50, 1433–1448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01829-1

Træen, B., Spitznogle, K., & Beverfjord, A. (2004). Attitudes and use of pornography in the Norwegian population 2002. The Journal of Sex Research, 41, 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490409552227

Wang, R. J., Huang, Y., & Lin, Y. C. (2007). A study of masturbatory knowledge and attitudes and related factors among Taiwan adolescents. Journal of Nursing Research, 15, 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jnr.0000387619.10554.f5

Wolf, C. (2012). Exploring the sexual attitudes of physician assistant students: implications for obtaining a sexual history. The Journal of Physician Assistant Education, 23, 30–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/01367895-201223040-00007

Zhana, V., & Ritch, C. S. W. (2010). Correlates of same-sex sexuality in heterosexually identified young adults. The Journal of Sex Research, 47, 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490902954307

Zuo, X., Lou, C., Gao, E., Cheng, Y., Niu, H., & Zabin, L. S. (2012). Gender differences in adolescent premarital sexual permissiveness in three Asian cities: effects of gender-role attitudes. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50, S18–S25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.001

Funding

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad de Huelva/CBUA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

No potential competing interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Blanc, A. Attitudes toward sexual behaviors: relationship with gender and sexual orientation. Curr Psychol 43, 1605–1614 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04398-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04398-3