Abstract

Psychological empowerment (PE) is a subjective, cognitive and attitudinal process that helps individuals feel effective, competent and authorized to carry out tasks. Over the last twenty years, research into PE has reported strong evidence reaffirming its role as a motivational factor in organizational psychology. In this study, the aim is to systematically review, analyze and quantify correlational empirical research focusing on empowerment, as understood by the theory developed by Spreitzer et al. (1995a, b), using meta-analytical techniques. The study also analyses the antecedents and consequences of PE and explores potential moderators of the relationship between this variable and its correlates. The electronic search encompassed studies dating from the publication of Spreitzer's empowerment scale (Academy of Management Journal, 38, 1442–1465, 1995b) up to January 2019. It was conducted in database aggregators, as well as in Metabus, occupational psychology journals and doctoral thesis repositories. Of the 1110 records identified, 94 were included in the meta-analysis. Most of the studies included used purposive or convenience sampling and had a cross-sectional study design. We focused on searching for studies that use a survey analysis approach. We extracted information about effect size (ES) in the associations between PE and its antecedents and consequences, and used the Comprehensive Meta-analysis 2.0 program to carry out the analyses (Borenstein et al., 2005). Effect size was calculated as the Pearson correlation (r), processed using Fisher's Z transformation. A random effects model was used and heterogeneity was analyzed to detect moderator variables. In relation to antecedents, in all meta-analyses, non-significant results were found only for education (r = -.001, CI [-.06, .06]) and organizational rank (r = .10, CI [-.16, .36]). All meta-analyses focusing on the association between psychological empowerment and its consequences returned significant results. Job satisfaction (r = .50) and organizational commitment (r = .51) had the largest effect sizes. Our results suggest which factors may be more important for generating empowerment among employees in accordance with the profession in which they work and their culture of origin. The main novelty offered by our results is that they indicate that age moderates the relationship between empowerment and the majority of the antecedents studied, a finding not reported in other meta-analyses. The present meta-analysis may help encourage organizations to pay more attention to PE, focusing their efforts on improving or strengthening certain structures or factors. Empowerment initiatives or programs focused on employee well-being lead to a workplace in which people are motivated and have a sense of purpose. Our results allow us to recommend interventions that enhance and improve the antecedents of EP. Finally, the present meta-analysis may help encourage organizations to pay more attention to the antecedents and consequences of PE, focusing their efforts on improving or strengthening certain structures or factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Empowerment theories

Over the last twenty years, research into psychological empowerment has reported strong evidence reaffirming its role as a motivational factor in organizational psychology. The term "empowerment" was coined in 1977 by Kanter, who identified it as the cornerstone for improving quality and service in organizations. Kanter believed that by empowering workers, organizations could ensure that they responded more flexibly to the different situations which may arise, instead of merely obeying rules in an automatic fashion. The aim was to give workers greater control over their resources and more access to information, in order to enable them to deal more effectively with customer requirements and even elevate their status within the organization. Kanter's social-structural perspective was therefore focused on empowering structures, policies and practices, which she viewed as indicators of empowerment. Subsequently, other authors have also identified these same elements as contextual antecedents of empowerment (Seibert et al., 2004).

The first empowerment theories did not focus only on organizations. Indeed, authors such as Rappaport (1984) and Zimmerman (2000) considered the concept to be a key mechanism of community psychology, perceiving it as a process in which people, organizations and communities gain greater control over their lives (Rappaport, 1984). Zimmerman (2000) argued that empowerment is a multilevel construct that can be analyzed at different levels: individual, organizational and community. Moreover, within each level of analysis, empowerment can be understood as both a process (a mechanism through which people gain control and influence over their lives) and an outcome (the consequence of different processes). For example, activities, actions and structures may be empowering, and the outcome of these processes is a feeling of empowerment (Zimmerman, 2000). According to this author, psychological empowerment refers to the individual level of analysis (Zimmerman, 1995), although he also argued that it may take different forms, depending on the people and contexts that surround it, and is not, therefore, a static concept. Consequently, he broke psychological empowerment down into three components: intrapersonal, interactional and behavioral. The intrapersonal component refers to people's self-perceptions and includes motivation to control, perceived competence and self-efficacy, and perceived control in specific domains.

Conger and Kanungo (1988) are generally considered to be the first authors to talk about the concept of psychological empowerment (PE). They distinguished between empowerment based on management and social influence literature, and that based on psychology literature. They defined empowerment as a relational construct in the practice of management, since it describes the process by which a leader shares their power with their subordinates in a dynamic relationship. However, they also recommended that empowerment be understood as a motivational construct, as (they argued) it is indeed viewed in psychology literature. They defined empowerment as "a process of enhancing feelings of self-efficacy among organizational members through the identification of conditions that foster powerlessness and through their removal both by formal organizational practices and informal techniques of providing self-efficacy information" (p.474). They therefore distinguished between different meanings of empowerment: empowerment in management terms, as an attempt to delegate or share power; and empowerment in psychological terms, as a means of motivating by enhancing personal efficacy.

Thomas and Velthouse (1990) further developed the motivation-centered theory of PE defined by Conger and Kanungo (1988). They refined the model, viewing empowerment as a motivational factor linked to intrinsic task motivation and specifying the set of cognitive components aimed at generating this intrinsic motivation: impact, competence, meaning and choice or self-determination. Impact refers to the degree to which one behavior stands out from the rest when attempting to achieve one's goals, and can be understood as the act of obtaining the desired effect through excellent conduct in a specific activity. Competence refers to the degree of skill demonstrated by the individual in the required task. This component coincides with the construct proposed by Bandura (1977) in the field of clinical psychology, known as self-efficacy (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990). Meaning is the "value of the goal in relation to a person's ideals or standards". It represents the psychological energy invested in a task. Finally, self-determination is the perception of having a choice about what one does, and "involves causal responsibility for a person's actions" (p.673).

Spreitzer (1995a) continued conceptualizing empowerment by focusing on the workplace, building on previous studies published by Thomas and Velthouse (1990). She developed a questionnaire to measure PE at work, including the four dimensions proposed by Thomas and Velthouse (1990), which she herself had subsequently identified independently (Spreitzer, 1992). These four dimensions (impact, competence, meaning and self-determination) correspond to the intrapersonal component of empowerment defined by Zimmerman (1995). Spreitzer (1995b) defined PE as a motivational construct that reflects an active orientation and self-perception of one's capacity to shape one's own work role and is manifested in four cognitions. She also argued that each of the four dimensions proposed for evaluating PE contributes to a global construct of empowerment. However, although the lack of any one dimension may diminish empowerment, it will not eliminate it altogether.

According to the theories outlined above, psychological empowerment may be defined as a cognitive, subjective and motivational process by which individuals perceive themselves as effective and competent for carrying out tasks, with sufficient capacity to ensure their completion. Moreover, the tasks themselves are deemed relevant and meaningful, and individuals feel they have freedom of choice in relation to them. The most comprehensive theory of PE is that developed by Spreitzer (1995a, b). Her model includes both the social-structural antecedents of PE and its behavioral consequences. Seibert et al. (2011) carried out the first meta-analytical review of the concept of PE, integrating other theoretical approaches also, such as the social-structural one and that based on teams. Some years later, Maynard et al. (2013) conducted another meta-analysis, analyzing PE in teams and coding the studies aggregated to team level. Neither of these meta-analyses focused specifically on Spreitzer's measure of psychological empowerment, and both included other measures in their systematic reviews (Menon's empowerment scale (1995) in the first and Kirkman and Rosen's (1999) measure of team empowerment in the second).

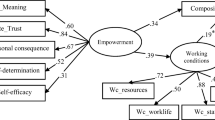

The aim of the present study is to perform a systematic review of the concept of psychological empowerment, using meta-analytical techniques. To this end, it analyzes and quantifies correlational empirical research focusing on PE, as understood by the theory developed by Spreitzer (1995a, b). The ultimate aim is to gain greater insight into the antecedents and consequences of the concept of PE. The study also explores potential moderators of the relationship between empowerment and its correlates and compares the results obtained with those reported by previous meta-analytical studies, in order to highlight the principal differences and suggest possible avenues of future research. Moreover, previous meta-analyses have highlighted a lack of research into certain organizational variables that have become highly relevant to the field of work psychology over the past decade, identifying, for example, a need for studies that explore the relationship between psychological empowerment and variables such as job crafting, engagement and organizational identification. For this reason, in the present study, we analyze whether this gap in the literature is still evident. Figure 1 shows the model proposed for the meta-analysis.

Antecedents of psychological empowerment

Spreitzer (1995b) included the contextual antecedents of PE in her model, positing that role ambiguity, sociopolitical support, access to information, access to resources and a work unit culture would be seen as empowering by workers. Other individual or characteristic personality factors, such as locus of control and self-esteem, have also been viewed as influencing cognitions of empowerment and may generate greater intrinsic motivation (Spreitzer, 1995a). Based on these previous studies, we distinguish between two types of factor in relation to the antecedents of PE: 1) psychosocial and organizational factors, and 2) individual worker characteristics.

Psychosocial and Organizational Factors

Structural and high-performance managerial empowerment practices

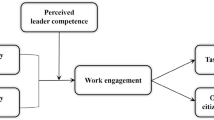

This group includes both structural empowerment and high-performance managerial practices. Access to organizational empowerment structures influences perceptions of power in the work environment (Kanter, 1977). The elements that make up structural empowerment are learning opportunities, access to information, access to resources and access to support in the workplace (Kanter, 1977). As Seibert et al. (2011) proposed in their meta-analysis, we also include high-performance practices in this group, since they are believed to improve performance by increasing the amount of information and skills workers have in relation to their job. The factors included in this group refer to managerial practices oriented towards offering workers greater access to support, resources, information, learning, innovation and growth, which in turn act as motivational and empowering elements. This category reflects the extent to which jobs or managers provide workers with opportunities in relation to the different variables mentioned. In terms of structural empowerment, Monje Amor et al. (2021) observed that psychological empowerment partially mediated the positive link between this variable and work engagement, which in turn was related to better task performance and lower intention to quit. The categories and primary variables included in the present meta-analysis are outlined in detail in the Appendix (Tables 6 and 7).

-

Hypothesis 1a: Structural and high-performance managerial empowerment practices in the organization will, in general, be positively associated with PE.

Leadership

The leadership factor encompasses all those practices or forms of leadership that are geared towards motivating workers and therefore seek to enhance their perception of empowerment. Leadership initiates a motivational process leading to empowerment and employees also tend to feel increasingly empowered when their leaders behave in a way that is viewed as positive (Laschinger et al., 2014). Indeed, some questionnaires on leadership styles suggest that empowerment may form part of the transformational leadership process. Specifically, the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ)—Short Form 5X (Avolio & Bass, 2004) includes a dimension called extra effort. This factor reflects the degree to which a leader is able to motivate an employee to do more than they expected to do, and to what extent that same leader manages to increase their desire to work hard and to succeed. Transformational leadership posits that transformational leaders are those who are able to involve and therefore empower their followers by fostering identification with goals, values and other members of the organization (Kark et al., 2003).

Rodríguez et al. (2017) also take into account the conceptual overlap between transformational leadership and authentic leadership. Authentic leadership has been considered a latent construct that serves as the foundation for transformational leadership (Avolio & Gardner, 2005) and contributes to the formation and development of members’ psychological capital (Jang, 2022). The ability of an authentic leader to develop their followers’ psychological capital helps empower them. Empowerment has been proposed as the mechanism through which authentic leadership influences performance (Walumbwa et al., 2007).

For its part, Leader-member exchange theory holds that the quality of the relationship between a leader and their followers plays a key role in determining how workers respond to their work environment (Davies et al., 2011). Arnold et al. (2000) describe empowering leaders as those who facilitate employee performance by enabling and encouraging workers in their work roles. Other authors have also argued that charismatic leadership is associated with a wide range of positive organizational outcomes and charismatic leaders are able to empower their followers to act beyond their expectations (Hepworth & Towler, 2004). Sylvia Nabila et al. (2021) found an indirect positive relationship between leadership styles (transformational leadership and transactional leadership) and task performance, with this relationship being mediated by psychological empowerment. In light of the above, we hypothesized that certain leadership styles would lead to major changes in followers' attitudes and behaviors, prompting them to accomplish more than expected.

-

Hypothesis 1b: Empowering, transformational and charismatic leadership styles and behaviors will be positively and significantly associated with workers' PE.

Social support and trust in the organization

This category includes sociopolitical support, support from the organization, rewards or income and trust in the organization. Spreitzer (1996) argued that certain managerial practices that are likely to improve sociopolitical support encourage people to trust each other, which in turn reduces the forces of domination at work and enhances empowerment. This category is closely linked to the "structural and high-performance managerial empowerment practices" one, the main difference being that, in this group, the emphasis is not on opportunities for or access to managerial elements, but rather on workers' perceptions of the support provided by the organization. The category "social support and trust in the organization" refers to the individual's perception of real rewards, trust and support, beyond the opportunity to access certain elements.

Interpersonal, mutual or dyadic trust between workers and supervisors has been found to facilitate activities in terms of organizational behavior and enables workers to feel empowered (Ergeneli et al., 2007). Seibert et al. (2011) refer to sociopolitical support as the degree to which work-related elements provide workers with material, social and psychological resources. According to Maynard et al. (2013), organizational support "can include actual resources that the team is able to obtain from other entities within an organization, [as well as] communication and coordination with other teams". As such, interpersonal trust and sociopolitical or organizational support through either resources or rewards can be considered facilitating factors that help enhance workers' motivation, thereby empowering them. In this sense, a study carried out by Gill et al. (2019) supports the idea that trust predicts feelings of empowerment among subordinates, as well as reciprocal feelings of trust towards supervisors. Moreover, the results of this study also support the idea that empowerment may play a unique mediating role in the relationship between subordinates’ feelings of being trusted and their well-being and work attitudes.

-

Hypothesis 1c: Greater social support and trust in the organization will be positively and significantly associated with PE.

Work role and work content

This category includes variables that explain the characteristics of the work content and the clarity of work roles. The concept work role comprises the set of tasks/activities that an individual is expected to perform in their job. When their roles are ambiguous and there is no clear definition of the tasks they are expected to perform, workers cannot be psychologically empowered. Furthermore, opportunities for empowerment are limited when employees perform routine and repetitive tasks. According to Yukl and Becker (2006), “there is more potential for meaningful work and self-determination in jobs that have complex tasks and enriching job characteristics”.

Morgeson and Humphrey (2006) developed a measure to assess job characteristics and argued that many terms have been used to describe similar job characteristics (defined as the attributes of the task, the job itself, and the social and organizational environment). According to these authors, the association between work characteristics and outcomes is moderated by several factors, one important one being psychological empowerment. Moreover, it has also been argued that although some employees may respond more positively than others to motivational characteristics, very few respond negatively (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006).

Towsen et al. (2020) found that authentic leadership exerts its influence on work engagement through psychological empowerment, regardless of the level of employees' role clarity. However, these authors also suggested that, contrary to expectations, the nomological proximity of authentic leadership and role clarity may be linked to this result. Spreitzer (1996) found a strong negative association between role ambiguity and PE and Karasek (1979) developed the demand-control at work model to explain job strain in terms of the balance between the demands of the job and the level of control (opportunities to develop personal skills and decision latitude) enjoyed by workers over them. High-stress jobs, characterized by high demands and low control, have been associated with lower psychological empowerment levels among workers (Laschinger et al., 2001a, b). A negative work environment may lead to demotivation and the inability to carry out the tasks required by the job. According to conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, 2001), a negative work environment is one with too few resources. This lack of resources results in workers’ inability to perform their assigned tasks or to obtain new resources to minimize the problem. According to Zhou and Chen (2021), the loss of resources leads to stress, which in turn generates an iterative spiral. Psychological empowerment can prevent these resource loss spirals.

-

Hypothesis 1d: An adequate work environment, with well-defined roles, an absence of excessive demands and perceived control over one’s job, will be positively and significantly associated with PE.

Individual worker characteristics

This category includes worker characteristics such as organizational rank, organizational tenure and education level. These variables feature as control or demographic variables in many studies (Llorente-Alonso & Topa, 2018; Wang & Howell, 2012), although they are only considered key variables in a few (Malik & Courtney, 2010). In the present study, we view individual characteristics (tenure, rank in the organization, education, etc.) as proxy variables indicating the worker’s level of knowledge, skill or experience, as well as their contribution to the organization. These proxy variables make it possible to obtain others of greater interest, through a correlation with the inferred value.Seibert et al. (2011) argued that individual characteristics are linked to empowerment.Variables related to human capital and employees' demographics are closely linked to career success (Wayne et al., 1999), and may have a positive impact on worker empowerment.

Significant results have been reported which suggest that these variables are associated with greater worker empowerment, although a meta-analysis encompassing all research to date is required since, in some cases, the results are contradictory. Spreitzer (1996) found significant associations between education level and PE, and in a sample of healthcare workers, Koberg et al. (1999) observed greater empowerment among those who had been with their organization for longer and had a higher rank. However, these authors found no significant association between education and empowerment. Prabha et al. (2021) found that faculty members with above-average age exhibited greater psychological empowerment, motivation and satisfaction. Furthermore, faculty members with above-average experience possessed a higher level of PE and satisfaction. These results prompt us to hypothesize that experience and organizational tenure may lead to greater empowerment.

Moreover, this category also includes personality factors such as locus of control, attributional style and self-control, etc. The extant research suggests that workers with an internal locus of control have higher expectations of their impact on certain tasks than those with an external locus of control (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990). According to the cyclical and dynamic model established by Thomas and Velthouse (1990), interpretive styles influence the way in which individuals can empower or disempower themselves.

-

Hypothesis 2a: Greater organizational tenure will be associated with greater PE.

-

Hypothesis 2b: Higher organizational rank will be positively and significantly associated with PE.

-

Hypothesis 2c: Higher education levels will be associated with greater PE.

-

Hypothesis 2d: Positive personality characteristics will positively influence PE.

-

Hypothesis 2e: Negative personality characteristics will be negatively and significantly associated with PE.

Consequences of psychological empowerment

Many studies have sought to analyze the consequences of PE. Spreitzer (2008) highlighted the importance of feeling empowered at work for obtaining positive individual outcomes. Other meta-analyses have divided the consequences of PE into two groups. For example, Seibert et al. (2011) distinguished between attitudinal and behavioral consequences, whereas Maynard et al. (2013) made a distinction between performance variables and affective reactions. In this study, we establish three categories: workers' affective reactions, workers' attitudinal reactions and the actions or behaviors generated by empowerment. We therefore distinguish between the emotional reactions generated by the feeling of empowerment, the tendency or willingness to act in a certain way and the behaviors generated by PE.

Workers' attitudinal reactions

Attitude can be defined as a state of mental readiness, organized through experience, which has a direct influence on a person's behavior (Allport, 1935). This tendency to act in a certain way is considered to be directly influenced by motivational variables. Some studies have associated greater PE with a weaker turnover intention (Islam et al., 2016), and Avolio et al. (2004) argued that empowered employees see themselves as more capable and more able to significantly influence the work they perform. They are also more likely to make an additional effort, act independently and be more committed to their organization. Higher levels of PE have been associated with greater organizational commitment, although some studies have found differences in the degree of this commitment in accordance with the country in which the data were collected (Ahmad & Orange, 2010).

Aljarameez (2019) conducted a study in which psychological empowerment was found to have a small moderating effect on the relationship between structural empowerment and continuance commitment. In most of the studies included in the meta-analysis presented here, organizational commitment refers to the Three-Dimensional Model of Organizational Commitment, which encompasses affective, continuance, and normative commitment; and studies include a general measure of commitment made up of these three components (Allen & Meyer, 1990).

However, in the studies by Chen et al. (2011), Kabat-Farr et al. (2018), Redman et al. (2009) and Hill et al. (2014), only the affective commitment subscale was used. For their part, Janssen (2004) and Raub and Robert (2012) used the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire developed by Mowday et al. (1979).

-

Hypothesis 3a: Greater PE will be associated with stronger organizational commitment.

-

Hypothesis 3b: PE will be negatively and significantly associated with turnover intention. The more empowered the worker, the weaker their intention to leave the organization.

Workers' affective reactions

Laschinger et al. (2001a, b) argue that the strategies proposed in Kanter's empowerment theory have the potential to reduce job strain and improve employee job satisfaction. They theorize that greater psychological empowerment provides an understanding of the mechanisms that intervene between structural work conditions and key organizational outcomes. Therefore, according to Affective Event Theory, when employees are excited about and immersed in their work, they are more likely to want to make a greater contribution to their organization (Park et al., 2021). According to this theory, dispositions and work events can lead to affective reactions, which in turn generate affect driven behavior (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996).

Job strain occurs when workers are subject to many psychological demands yet have little control over them (Karasek, 1979). Prolonged strain results in an occupational syndrome known as burnout, which is characterized by emotional and physical exhaustion, depersonalization and low levels of perceived personal accomplishment (Maslach & Jackson, 1982). Burnout occurs in the presence of chronic stressors. The original model encompassed only human service providers and education workers, although it has subsequently been found to be applicable to any occupation (Leiter & Schaufeli, 1996). Calvo and García (2018) argue that PE is the result of structural empowerment, and may therefore act as a protective factor against chronic stressors in the workplace. Laschinger et al. (2001a, b) found that greater PE strongly influenced both the degree of occupational strain felt by workers and their job satisfaction. According to Heron and Bruk-Lee (2019), the experience of high stress at work interferes with the process whereby empowerment may impact desirable work attitudes and safety-related behaviors. The findings of their study highlight the importance of understanding the effects of workplace stress for predicting critical outcomes.

Job satisfaction is one of the most widely studied affective reactions among workers, and is considered an indicator of psychological health and well-being. According to Spector (1997), job satisfaction is the way people feel about their job and its different aspects, and is linked to the degree to which they like or dislike it. This author also argues that workers' level of satisfaction may affect behaviors linked to good organizational functioning. For example, workers with greater PE, and therefore a stronger perception of their own competence and impact, tend to feel more satisfied with their jobs. A recent meta-analysis has shown that the direct association between psychological empowerment and job satisfaction is strong, positive and significant (Mathew & Nair, 2021).

Finally, Thomas and Velthouse (1990) identified the four dimensions of PE as the cognitive components of intrinsic task motivation. However, as Gagné et al. (1997) pointed out, although these authors equate feelings of empowerment with intrinsic motivation, they also argue that the four components of empowerment are a proximal cause of intrinsic task motivation and satisfaction (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990). Gagné et al. (1997) believed that motivation is not conceptually the same as its antecedents, but is rather the energy that prompts behavior. For its part, competence is a previous cognitive evaluation of both one's context and oneself. The more positive the result of the evaluation, the more energy is generated. Consequently, in the present study, although PE is considered a motivational factor, we do not assimilate it into the concept of intrinsic motivation, but view it rather as an antecedent.

-

Hypothesis 3c: PE will be negatively and significantly associated with job stress/strain and indicators of burnout. The greater the PE, the lower the level of job strain.

-

Hypothesis 3d: PE will be positively associated with job satisfaction.

-

Hypothesis 3e: PE will positively influence workers' intrinsic motivation.

Worker actions/behaviors

Finally, the aim is also to determine how PE affects worker behaviors, specifically performance, creativity, innovation and organizational citizenship. A key assumption of Thomas and Velthouse's cognitive empowerment model (1990) is the existence of a continuous cycle encompassing environmental events, task evaluations and behaviors. Environmental events provide information about the consequences of behaviors. Tasks can therefore be evaluated in accordance with PE, providing feedback regarding the individual's behavior (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990).

According to Spreitzer (1995a), intrapersonal empowerment mediates the relationship between social-structural antecedents and innovative behavior. Innovation is the successful implementation of creative ideas within an organization (Amabile, 1988). Empowered individuals who perceive themselves as competent are more likely to be innovative and creative due to their expectations of success, and because they feel less constrained by the rule-based aspects of their job (Amabile, 1988). Moreover, empowerment encourages members of the team to contribute in different ways to common activities (Spreitzer, 1999). It is therefore to be expected that more empowered individuals will perform better, engage in more organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) and adopt a more active attitude to their job (Spreitzer, 2008). Sylvia Nabila et al. (2021) suggested that empowered employees are very responsible, make an extra work effort and are more creative in their jobs, which together tends to enhance their performance at work. Khan and Ghufran (2018) argue that the relationship between empowerment and OCB stems from the fact that whenever an employee feels that their job has meaning and that they themselves enjoy independence and freedom, are competent and have an impact, the more their behavior is oriented towards a direction that serves the organization—helping colleagues and customers and being courteous, conscientiousness and civic-minded.

-

Hypothesis 4a: PE will be positively associated with creativity and innovative behavior among workers.

-

Hypothesis 4b: PE will positively influence job performance.

-

Hypothesis 4c: PE will be positively associated with organizational citizenship behaviors.

The specific categories and primary variables of the antecedents and consequences of PE are outlined in detail in the Appendix (Tables 6 and 7).

Variables that moderate the relationship between PE and its antecedents and consequences

Age range

Participants were grouped into four age ranges: 19–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years and over 50 s. Recent research has highlighted age discrimination as a common problem in organizations (Furunes & Mykletun, 2010). Age discrimination is the process by which workers are discriminated against solely on account of their age. Schermuly et al. (2014) have suggested that age discrimination may diminish PE and its components in a number of different ways, with stereotypes decreasing both performance and workers' perceptions of their own competence, and the selection of younger workers to the detriment of older ones reducing meaning. They also argue that the exclusion of older workers from decision-making and engagement processes may diminish both self-determination and impact.

In contrast, Dimitriades and Kufiduse (2004) found that empowerment was significantly associated with workers' age, and Spreitzer (1996) identified a positive relationship between age and the competence dimension of empowerment. Furthermore, after categorizing her sample into age ranges, Ozaralli (2003) found significant differences between those aged between 20 and 30 years and those aged over 40, concluding that older workers feel more empowered.

In light of the above, the aim here is to analyze whether workers' age influences the relationship between PE and either it antecedents (Hypothesis 5a) or its consequences (Hypothesis 5b). For example, a larger effect size (ES) in the relationship between individual worker characteristics and PE would indicate that the older the worker, the more their personal characteristics influence their PE.

Cultural differences

Recent research has compared the moderator effects of the collectivist and individualist outlooks on PE and its consequences, including job satisfaction and extra-role performance. Fock et al. (2011) found that the collectivist outlook heightened the effect of self-determination on job satisfaction. Cho and Faerman (2010) suggested that higher levels of organizational collectivism had a stronger effect on the relationship between PE and extra-role performance than lower levels of this outlook, and Kirkman and Shapiro (2001) found that teams with a higher level of collectivism reported more empowerment. It is therefore likely that people working in collectivist cultures define themselves as part of a group and prioritize group goals to a greater extent than those working in individualistic environments (Triandis, 2001). PE may be more effective in collectivist cultures because members of these cultures may react more strongly to signals that foster identification and inclusion, such as psychological empowerment (Seibert et al., 2011).

In contrast, other studies have reported opposite results. For example, Thomas and Rahschulte (2018) studied the moderating effects of power distance and individualism/collectivism on the relationship between empowering leadership and PE, finding that, in a sample from Rwanda, high levels of collectivism weakened the relationship between empowering leadership and PE among employees, whereas in the USA, the moderating effect of individualism enhanced this relationship.

In relation to power distance, Seibert et al. (2004) suggested that among people from cultures with a high power distance, a stimulating climate may generate feelings of stress rather than feelings of PE. According to Spreitzer (2008, p.27), in a high power-distance culture, workers may react less positively to PA, since "it may be culturally inappropriate for employees at low levels of an organizational hierarchy to have a significant say in their work". In these high power-distance cultures, it may be that bosses perceive employees with high levels of self-determination and impact as a threat.

Bearing in mind the contradictory findings reported by the literature, in this study, our aim is to explore whether the cultural characteristics of the sample (categorized in accordance with continental origin) influence the relationship between PE and its antecedents and consequences.

-

Hypothesis 6: We expect to find significant cultural differences in the associations between PE and its antecedents and consequences.

Profession

In their meta-analysis on the antecedents and consequences of PE, Seibert et al. (2011) suggested that the effectiveness of PE may differ in accordance with the type of occupation being studied. Specifically, employees from the services sector reacted to PE with greater job satisfaction than those working in the manufacturing industry. These authors also highlighted opposing predictions in the literature: if contact with customers provides greater job motivation, the need for PE may decrease; yet at the same time, said contact may increase PE, since workers have more opportunities for discretionary behavior (Seibert et al., 2011). In the present study, the aim is to determine whether type of occupation affects the relationship between PE and its antecedents and consequences.

-

Hypothesis 7a: Associations between PE and its antecedents will have larger ESs in those professions involving close contact with, or the provision of services to, other people.

-

Hypothesis 7b: Associations between PE and its consequences will have larger ESs in those professions involving close contact with, or the provision of services to, other people.

The present study therefore seeks to answer the following research questions:

-

What antecedents and consequences are associated with psychological empowerment?

-

What variables moderate the relationship between PE and its antecedents and consequences?

Following the proposal made by Rassol et al. (2019), below is a summary of the structure followed by the paper. Section 2 is devoted to the Method. This section outlines the research method, population, sample and inclusion criteria, describes the operationalization of the variables and the evidence provided by the extant literature, and specifies the data analysis strategies used. Section 3 includes a description of the studies included in the meta-analysis and the results of the data analysis; and Sect. 4 provides a discussion of the results, outlines limitations, suggests avenues for future research and explores theoretical and practical implications.

Method

Research approach

The present study adopts a quantitative approach with the aim of emphasizing the accuracy of the measurement procedures and providing evidence in support of Spreitzer's psychological empowerment scale and its relationship with other organizational variables. The aim is to analyze existing confirmatory and objective research into empowerment. We focused on searching for studies that use a survey analysis approach, since this approach is common and enables broad level data to be collected from the target population (Wang et al., 2022). Moreover, findings from a large sample can be significantly generalized to the population (Asghar et al., 2022). The research method used in this meta-analysis has the advantage of providing more precise results in relation to the research problem under analysis, since said results are a mathematical aggregate of those reported by several studies examining the variables in question (Ankem, 2005).

To carry out this meta-analytical study, we followed the guidelines provided by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) declaration (Moher et al., 2009). The electronic search encompassed studies dating from after the publication of Spreitzer's paper outlining the construction and validation of the PE scale (1995b) up until January 2019. It was conducted in digital databases and database aggregators (Web of Science, Ebsco Host, Cochrane library, Pubmed, Science Direct). Figure 2 lists all the databases used in the meta-analysis. We also used Metabus (Bosco et al., 2015), a research synthesis platform which offers an advanced search and synthesis engine, thereby representing a fast first step for conducting meta-analyses. A manual search was also performed of journals that habitually publish research in the field of Occupational and Organizational Psychology and which may have attracted studies on psychological empowerment. We included the Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, the Journal of Applied Psychology, and the Academy of Management Journal in our search.

Flow diagram of the different phases of the systematic review (according to PRISMA). Note: In relation to EBSCO HOST, the following databases were selected from the database aggregator (Medline, Academic Search Premier, PsycInfo, PsycArticles, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, ERIC, Open Dissertations, PSICODOC, MLA International Bibliography with Full Text, MLA Directory of Periodicals, EBSCO eClassics Collection (EBSCOhost), International Political Science Abstracts, E-Journals, eBook Education Collection (EBSCOhost), eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), ERIC, Philosophers Index with Full Text, Library & Information Science Source Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts, Teacher Reference Center, and The Serials Directory)

For the majority of the databases searched we used the (TX Empower*) AND (TX Spreitzer) search strategy. In Web of Science, Pubmed and Science Direct, we used the following search chain in order to limit the results and distinguish between different types of empowerment: (Psychological Empowerment) OR (Empower*) NOT (Structural Empowerment) AND (Spreitzer). The search strategy used identified a total of 1110 records. We also identified 13 other studies from other sources, such as doctoral thesis repositories.

After checking the results, 336 duplicate studies were removed. The remaining 787 records were assessed on the basis of their abstracts, with 547 being excluded for not complying (for various reasons) with the inclusion criteria (see Fig. 2). Consequently, 240 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 146 were excluded for being outside the scope of the review (n = 40), being reviews or meta-analyses (n = 2), not featuring the complete PE measure, featuring only certain dimensions (n = 43), being theoretical or qualitative studies (n = 4), not providing Pearson correlation measures (n = 46) or focusing on empowerment measures other than the theory developed by Spreitzer (n = 11).

Population, sample and inclusion criteria

To be included in this meta-analysis, articles had to comply with the following criteria: (a) they had to present a piece of correlational empirical research with a sample of workers from any organization; (b) they had to provide Pearson correlation coefficients (or equivalent) of the associations between PE and its antecedents and consequences; (c) the instrument used to measure PE had to be the 12-item scale developed by Spreitzer (1995b), and articles had to provide a general measure of PE; and (d) they had to be written in English, French, Italian or Spanish.

A total of 94 empirical articles were finally included in the meta-analysis, providing 331 independent effect sizes (ESs) with a total of 42,212 participants. Most of the studies included used purposive or convenience sampling and had a cross-sectional study design. Bhatnagar (2005) used a survey design, but the sampling was randomized, with the organization being chosen first, followed by the sample.

Operationalization of the variables and the evidence provided by the extant literature

First, we compiled a Record Protocol for the moderator variables included in the articles, distinguishing between methodological, substantive and extrinsic characteristics (Sanchez-Meca, 2010). The methodological characteristics were sample size, type of non-experimental design (cross-sectional vs. longitudinal) and the reliability measure pertaining to Spreitzer's scale. Substantive characteristics were those linked to participants and context. In relation to participants, the percentage of women in the sample was coded, along with participants' age range (distributed across four groups: 19–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years and over 50 s) and professional category (healthcare, security, services, industry/computing, education and banking/administration). The contextual variable was the location of the study (continent). Extrinsic characteristics were the year in which the study was carried out and the source of publication (published vs. unpublished). Articles were coded independently by two coders. To ensure consistency and guarantee reliability, the coders met to review the results and reach a consensus independently for each sample (Orwin & Vevea, 2010).

We also coded the antecedents of PE, distinguishing between psychosocial and organizational factors and individual worker characteristics. Variables linked to the consequences of PE were divided into three groups: affective reactions, attitudinal reactions and worker behaviors.

Data analysis strategies

In this meta-analysis, we extracted information about effect size (ES) in the associations between PE and its antecedents and consequences. We used the Comprehensive Meta-analysis 2.0 program to carry out the analyses (Borenstein et al., 2005). Effect size was calculated as the Pearson correlation (r), processed using Fisher's Z transformation. To calculate ES, subgroups were combined using the random effects model. The significance level of Z and the confidence intervals (95%) were analyzed to determine the statistical significance of each association between PE and its correlates. To interpret the magnitude of the ES, we followed the empirical guidelines proposed by Hemphill (2003): r < 0.20 = small ES; r between 0.20 and 0.30 = medium ES; and r > 0.30 = large ES.

To determine heterogeneity, the Q statistic and the I2 index were calculated. If the Q statistic reaches statistical significance, this means that the different ESs are heterogeneous and are not well represented by the mean effect size. The I2 index quantifies the heterogeneity existing between studies in percentage terms (Sanchez-Meca, 2010). If there is heterogeneity between the ESs, then the influence of moderator variables must be examined. I2 indexes of around 50% or 75% may respectively be interpreted as medium and high (Borenstein et al., 2009). In this meta-analysis, since the I2 values were high, analyses of variance were performed using weighted ANOVA techniques. The age range of the sample was analyzed, along with continent of origin and type of profession, with the aim of determining whether or not these variables moderated the associations observed between PE and its correlates.

Results

Description of the studies

Of the 94 articles included in the systematic review, 4 were published between 1995 and 2000, 24 between 2001 and 2009 and 66 between 2010 and 2019. The majority were written in English. Only one was written in Spanish and five were in French. The mean age of participants in all samples was 36.15 (SD = 8.22). The percentage of women in the total sample was 55.90 (SD = 22.22). Samples mostly came from Asia and America (with 39 and 40 samples, respectively); Europe had 13 and Oceania and Africa had one each.

Antecedents of PE

Table 1 presents a meta-analytical summary of the antecedents of PE. We include the effect size for each meta-analysis, along with the Z significance level, the 95% confidence interval, the Q statistic and the I2 index. Of all the results found in the meta-analyses, only those pertaining to education (r = -0.001, CI [-0.06, 0.06]) and organizational rank (r = 0.10, CI [-0.16, 0.36]) were non-significant. The results of the meta-analyses of the associations between psychosocial and organizational variables and PE were significant, with large, positive ES values. The largest ES found (r = 0.40) was for leadership. These results support Hypotheses 1a, 1b, 1c and 1d. As regards individual worker characteristics, organizational tenure had a small ES (r = 0.12), negative personality characteristics a medium ES (r = -0.22) and positive personality characteristics a large ES (r = 0.31). These findings support Hypotheses 2a, 2d and 2e. In terms of heterogeneity, all I2 indexes were over 75%, a value interpreted by Borenstein et al. (2009) as indicative of high heterogeneity. Consequently, we evaluated the influence of the moderator variables as predictors of ES.

Consequences of PE

Table 2 presents a meta-analytical summary of the consequences of PE. All the meta-analyses carried out returned significant results. Job satisfaction (r = 0.50) and organizational commitment (r = 0.51) had the largest ESs. Turnover intention (r = -0.36) and job strain (r = -0.30) had large but negative ESs. Organizational citizenship behaviors were significant, but had a small ES (r = 0.18). These results support Hypothesis groups 3 and 4. The I2 indexes were high, with the exception of creativity (68.48%) and organizational citizenship behaviors (62.9%), for which medium values were obtained. Again, the decision was made to evaluate the variables influencing this heterogeneity between ESs.

Analysis of moderator variables

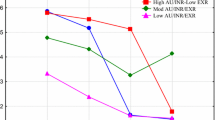

Table 3 presents the results of the weighted analyses of variance by participants’ age range. We calculated the QW statistic, which indicates the existence of homogeneity within each category, and the QB statistic, which indicates the existence of differences between the mean ES in each category. In relation to psychosocial and organizational variables, both types of statistic were significant in every meta-analysis carried out. This indicates that in addition to the workers’ age range, other relevant mediator variables exist that explain the heterogeneity observed among ESs. Work role and content (r = 0.35) and social support (r = 0.08) had smaller ESs among older age ranges.

As for individual characteristics, both positive (r = 0.47) and negative characteristics (r = -0.36) had larger ESs among older age ranges. Significant values were found only for organizational tenure among the middle age ranges: 30–39 (r = 0.17) and 40–49 years (r = 0.13). As regards the consequences of PE, only creativity was found not to be significant (QB = 3.84, p = 0.27). Organizational commitment obtained large ESs in all age ranges, whereas turnover intention (r = -0.61) had larger ESs in the upper age range. All affective reactions had larger ESs in the older age ranges, whereas performance was higher in the medium ranges. These results partially support Hypotheses 5a and 5b, since PE was found to vary in accordance with worker age range.

Table 4 presents the results of the ANOVAs by sample origin. In terms of psychosocial and organizational variables, work role and content (r = -0.05, CI [-0.10, 0.007]) were not significant for America, although they were for the other continents. Social support (r = 0.42), leadership (r = 0.46) and structural empowerment (r = 0.43) obtained larger ESs in collectivist cultures. Regarding individual characteristics, no significant differences were observed between the ESs for organizational tenure. Asian countries had larger ESs than America in terms of the influence of negative personality characteristics.

Significant differences were found for all the consequences of PE in terms of continent of origin. All continents obtained large, similar ESs for organizational commitment. Individualistic cultures had larger ESs in turnover intention (r = -0.63), job satisfaction (r = 0.77) and creativity (r = 0.47). Collectivist cultures only scored higher for job strain (r = -0.46). Large ESs were observed for performance in Europe and Africa, whereas Asia and America had moderate ESs. These results do not enable Hypothesis 6 to be rejected, since differences were observed in ESs in accordance with the continent on which the studies were carried out.

Table 5 presents the results of the ANOVAs by participant profession. Professions linked to health and education obtained larger ESs for social support (r = 0.38, r = 0.55). The ES for leadership was larger among those who worked in banking (r = 0.45) and industry/computing (r = 0.41). Structural empowerment obtained smaller values in the services sector (r = 0.29). The ES of work content was large in health and services, and negative in education (r = -0.51). As regards organizational tenure, the results for banking were not significant, whereas ESs were very small for all other professions. The largest ESs in the positive personality category were found for health (r = 0.28), services (r = 0.41) and education (r = 0.40).

Finally, in professions involving contact with people, the largest ESs were found for organizational commitment (r = 0.66), turnover intention (r = -0.61), job strain (r = -0.43) and job satisfaction (r = 0.73). Intrinsic motivation was higher in industry (r = 0.48) and banking (r = 0.41). No differences were observed between the ESs obtained for any worker behavior. These results partially support Hypotheses 7a and 7b.

Discussion

The present study aimed to carry out a systematic review and meta-analysis of correlational studies focused on the concept of PE developed by Spreitzer et al. (1995a, b). As well as enabling a better understanding of the antecedents and consequences of PE, the study also aimed to explore potential moderators of the relationship between this variable and its correlates. Finally, the aim was also to compare the results obtained with those reported by other meta-analyses of PE.

Antecedents of PE

Firstly, following the meta-analytical model tested by Seibert et al. (2011), the antecedents of PE were divided into two categories, psychosocial and organization factors, and individual worker characteristics. The four psychosocial factors (structural empowerment, leadership, work role and social support and trust in the organization) were found to have a significant, strong, positive effect on workers' PE. This finding is consistent with that reported by Seibert et al. (2011), who also observed strong associations between contextual factors and PE. Indeed, solid evidence exists of the relationship between certain characteristics of leaders and leadership styles and PE (Allameh et al., 2012; Bagget, 2015; Dust et al., 2018; Gumusluoglu & Ilsev, 2009; Yahia et al., 2017). As regards high-performance managerial practices, Maynard et al. (2013) studied them separately from structural empowerment in order to highlight the differences that exist in their relationship with PE. Nevertheless, these authors found correlations between PE and high-performance managerial practices that were similar to those found in relation to structural empowerment. In the present meta-analysis, high-performance managerial practices and structural empowerment were included in a single category, with the results indicating that they act as a strong antecedent of PE. In this sense, Messersmith et al. (2012) observed that building an effective human resources system may have a powerful influence on the attitudes and behaviors of individual employees. As regards social support and trust in the organization, the results indicate that when participants perceive real rewards, trust and support, this leads to greater PE. Both rewards received and income were included in this category, since they are considered tangible assets that can be perceived by workers. In the meta-analysis by Seibert et al. (2011), however, they were included in the high-performance managerial practices factor. As with the other psychosocial factors, work role and content were found to be strong correlates of PE.

The results pertaining to individual worker characteristics revealed that education and organizational rank did not influence PE. These results are consistent with those found by Seibert et al. (2011). However, they contradict those reported by Spreitzer (1995b), who found that, in demographic terms, more empowered employees tended to have higher education levels, greater tenure and a higher rank (Spreitzer, 2008). Our data suggest that although tenure in the organization does have an influence on PE, it is a weak one. In their meta-analysis, Maynard et al. (2013) found non-significant correlations between tenure and experience at the organization and PE. Further research and longitudinal studies are required to determine whether individual factors such as gender, age, education and organizational rank may offer a causal explanation for the differences observed in empowerment levels. Nevertheless, the fact that different meta-analyses have reported non-significant or low values in relation to these individual variables leads us to suspect that they are not relevant to empowerment.

In contrast, personality factors were found to be strong antecedents of PE, as indeed posited by the theory of PE (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990). Workers who often attribute negative organizational experiences or failures to uncontrollable sources tend to believe they cannot be changed. Moreover, they view effort and outcomes as independent factors. These perceptions may diminish empowerment and inhibit the development of positive expectations (Huang, 2012).

Consequences of PE

The consequences of PE were divided into three categories: affective reactions, attitudinal reactions and worker behaviors. All the factors included in the affective and attitudinal reactions categories were found to be strongly associated with PE. PE therefore acts as a motivational factor that may generate emotional reactions and dispose people to act in a positive manner within the organization. More empowered employees are committed to their organization and are less likely to want to leave, prompting them to behave in a way that contributes to the achievement of common goals. They also have strong affective reactions. They feel satisfied with their job, experience less strain or stress at work and have more intrinsic motivation, understood as the energy resulting from their assessment of the context as empowering. In the present meta-analysis, we believed it was important to separate attitudes from emotional reactions. However, other authors have analyzed these factors together, in the same group, obtaining similar results regarding the strength of their association with PE (Seibert et al., 2011; Maynard et al., 2013). Li et al. (2018) also found significant results in their meta-analysis of the relationship between PE and job satisfaction.

As regards worker behaviors, high, significant values were found for creativity. Employees with a greater degree of PE may feel more attracted to their work, propose more creative ideas and resolve more problems (Duan et al., 2018). Our results also indicate a statistically significant (although moderate) positive association between PE and performance and organizational citizenship behaviors. This finding is consistent with that reported by Seibert et al. (2011) and suggests that PE manifests as a motivational factor which impacts attitudes and emotions more than the direct achievement of targets and goals. Nevertheless, more longitudinal research is required in this sense to explore these indirect relationships between PE and worker behaviors, mediated by attitudes and emotions.

Moderators of PE: age, origin and professional area

In relation to the moderators of PE, our results indicate that age moderates the relationship between this variable and the majority of the antecedents studied. In terms of work role and content and social support, our results revealed that older workers were less empowered, and in relation to leadership and structural empowerment, it was the mid-range age groups that scored highest. Younger workers may be more influenced by organizational factors, reacting more strongly to their presence and therefore becoming more empowered than their older counterparts. This is consistent with that reported by Schermuly et al. (2014), who found that age discrimination may decrease perceived PE. Older workers may be discriminated against in the hiring process or not receive the same opportunities for professional development as their younger colleagues, which results in a drop in PE among older age groups. In relation to personality characteristics, higher levels of PE were found among older age groups. McCrae et al., (1999, p. 472) suggest that older adults differ from their younger counterparts by being better able to control their impulses, searching less for emotions and being more morally responsible. This may explain why older workers, who report greater perceived self-control, are more empowered than their younger counterparts.

In terms of the consequences of PE, no differences were observed in creativity in accordance with age. Abra (1989) argues that creativity may simply change rather than decline with age. Higher age ranges scored higher for turnover intention and affective reactions. Our results are consistent with those obtained by Thomas and Feldman (2009), who found that age was related to voluntary turnover and that race, tenure and education level helped explain the differences observed between the different age ranges. Similarly, Clark et al. (1996) proposed a U-shaped explanation for the relationship between job satisfaction and age, suggesting that young workers may feel satisfied because they have little work experience, but as they learn, they are better able to judge their working conditions, meaning that satisfaction may drop as they enter the middle age ranges. This finding is consistent with the association observed in our study between PE and job satisfaction.

Large ESs were found for organizational commitment in all age ranges, with values being slightly higher among the younger age groups. Younger workers may be more empowered and committed to their organizations at the start of their working life, since they do not have the benefit of being able to compare their current job with any previous ones. Finally, performance was higher in the middle age ranges and indeed, participants who had been working for longer at their organizations were only empowered in these ranges. These findings suggest that performance may be strongly influenced by tenure. Indeed, Suhonen (2019) found significant associations between age, tenure, general self-efficacy and performance.

The next moderator studied was the origin of the sample. In collectivist cultures, psychosocial factors and negative personality characteristics (antecedents of PE) had a stronger impact on workers' PE. Consistently with this, Walumbwa and Lawler (2003) also found that collectivist cultural orientations influenced perceptions of transformational leadership and work-related outcomes such as satisfaction and commitment. For their part, in a study focusing on Germany, Romania and China, Felfe et al. (2008) found that the correlation between leadership and employee attitudes was stronger among those from highly collectivist cultures.

Our results also suggest that personality characteristics such as external locus of control may negatively affect PE more strongly in collectivist and high power-distance cultures. This may be due to the fact that people with an external locus of control are often motivated by external rewards and are fearful of taking risks. In this sense, Elliot et al. (2001) found that more collectivist cultures were associated with greater negativism and more attention to negative personal information.

Significant differences were observed in all the consequences of PE in relation to the cultural origin of the samples. Cultures with a greater power distance scored higher for job strain. As suggested previously, an empowering climate may generate feelings of stress in these cultures, since it may be culturally inappropriate for workers at lower levels of the hierarchy to have a significant say in their work (Seibert et al. 2004; Spreitzer, 2008, p.66). Nevertheless, all the continents studied obtained high (and similar) scores for organizational commitment. Some authors have suggested that power distance must be fairly high to result in negative attitudes in response to empowerment practices (Robert et al., 2000), claiming that in some high power-distance cultures, such as India, for example, employees may prefer hierarchical structures, while in others, such as Mexico, they simply tolerate them. This implies that employees may react more negatively in some collectivist cultures than in others.

Our data also revealed that PE had a significant positive influence on turnover intention, job satisfaction, creativity and organizational citizenship behaviors in all cultures, although scores were higher in individualistic ones. The findings reported by previous studies in this sense are contradictory, with some observing higher satisfaction levels in collectivist cultures, and others reporting the same in individualistic ones (Hui et al., 1995; Harrison, 1995; cited by Noordin & Jusoff, 2010). Noordin and Jusoff (2010) therefore recommend that researchers exercise caution when using cultural values to try to understand human behaviors in organizations, arguing that although the attitudes and values of a country are usually rooted in society, they may also change over time as external environmental transformations take place. Higher levels of performance were observed in Africa in the presence of PE. In this sense, Jackson et al. (2006) found that psychological collectivism was positively associated with supervisor ratings of group member job performance and organizational citizenship behaviors.

As regards the influence of profession on the relationship between PE and its correlates, in our study we found that in professions characterized by providing a service to others, such as healthcare and education, workers were more empowered in the presence of social support and trust in the organization. This finding may be explained by the uneven distribution of gender across the labor market, since there is a predominance of women in these professions. For example, Liebler and Sandefur (2002) found that women tended to report giving and receiving more support to/from non-family members, and in a study carried out with healthcare workers, Wallace (2013) found that women received more empathy, attention, advice and work-related information from their colleagues than men. In stereotypically male professions with a stricter structural hierarchy, such as industry for example, leadership style was found to generate larger effect sizes in our study. García-Ael (2015) also found that, in leadership positions in occupations generally considered to be male dominated, characteristics linked to agency are strongly emphasized, thereby resulting in a strengthening of gender roles.

Work roles, perceived control and demands and positive personality characteristics resulted in greater PE in stereotypically female professions, such as healthcare and the services sector. The better defined the individual's role in the organization, the more likely they are to believe they have an impact on it (Boudrias et al., 2010). In a study carried out with hotel employees, Kim et al. (2009) found that the effect of role stress on job satisfaction was greater among female workers and supervisors than among male workers.

Finally, professions such as healthcare, education and services were also found to generate greater organizational commitment, turnover intention, job strain and job satisfaction. In contrast, intrinsic motivation was higher in industry and banking. Davies et al. (2011) found that women attach greater importance to prosocial values and have a stronger role identity as organizational citizens who provide aid to colleagues. Women also engage more often in group or individual-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors. Indeed, Rivera-Torres et al. (2013) have suggested that the generation of job strain follows a different pattern in men and women, and that social support mitigates job strain more among women than among men.

Limitations

The principal bias in the present study is publication bias. Published studies may not accurately represent all the studies carried out on empowerment and its correlates. We also included articles with small samples (Messersmith et al., 2012), which may have skewed the results. Another important bias is location bias, since we only took into account articles written in English, Spanish, Italian and French, which limited our opportunity to locate studies written in other languages on the topic under study.

Another limitation is linked to study design, since many of the correlational studies included our meta-analysis were cross-sectional in nature, thereby implying validity problems since no causal relationships can be established between constructs. Moreover, high correlations between constructs, as in the case, for example, of intrinsic motivation and PE, may suggest empirical redundancy (i.e., a lack of differentiation between the two). In cross-sectional research, it is not possible to empirically distinguish between constructs, due to their reciprocally causal relationship (Le et al., 2010). It is also important to highlight the fact that all the studies included in the present meta-analysis measured correlations between the variables analyzed and PE. However, in some, these variables were not classified as either antecedents or consequences of PE, and only their correlation was studied. In many cases, given the cross-sectional nature of the design, directionality cannot be assessed in any way other than in relation to existing literature on the subject. These theoretical considerations may result in classification bias. Furthermore, the variables analyzed were not always central to the study design, but were rather used as control data. This is the case, for example, with organizational rank and tenure. However, these variables are treated here as predictors of PE. Table 8 in the Appendix provides a list of the studies included in the meta-analysis and the variables they analyze as correlates of PE.

Finally, no distinction is made in the present study between individual and team psychological empowerment. The inclusion criteria were to have used Spreitzer's scale (1995b) as a measure of empowerment, and to have obtained a Pearson correlation measure (or equivalent) in order to calculate effect size. This lack of distinction between the individual and group levels may imply a degree of publication bias. Nevertheless, in the present study, priority was given to the concept of overall empowerment, without determining whether or not sample levels were aggregated.

Future directions and theoretical and practical implications

In our initial approach to the meta-analysis presented here, we included organizational identification as an antecedent of PE. Some authors believe that perceived PE may emerge in accordance with how employees identify with their organization, how they value it and how it contributes to their self-definition (Prati & Zani, 2013). An individual's sense of being part of their organization may result in a greater perception of power in the workplace (Prati & Zani, 2013). However, after reviewing the extant literature, we found a lack of correlation studies in this area. Further research is therefore required into the influence of organizational identification.

Another variable that we could not include due to a lack of existing studies was job crafting, a proactive behavior that enables employees to model their jobs and change certain physical, cognitive and relational aspects of their work activity (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Studies focusing on job crafting as a means of generating greater empowerment in organizations are becoming increasingly important (Hulshof et al., 2020) and future meta-analyses should strive to include these theoretical developments.

Furthermore, although considerable research has explored the antecedents of psychological empowerment, few studies have examined goal orientation. In some studies, psychological empowerment is viewed as the link between goal orientation or task characteristics and employee creativity (Matsuo, 2022), and one concluded that there was a positive interaction effect between developmental job experience and learning goal orientation on psychological empowerment (Matsuo, 2021).

After evaluating cultural differences in relation to PE, we believe it is important to recommend that managers make an effort to determine the prevailing cultural values in their organizations, and take national collectivism and power distance data into account also. However, although it is true that research has found that the origin of the sample affects both PE and its correlates, some authors have reported contradictory data in two collectivist countries, suggesting that caution should be exercised in this regard (Robert et al., 2000). The GLOBE project (Javidan & Dastmalchian, 2009) analyzed different cultural and leadership dimensions (which have important implications for management) in different countries, finding that managers need to know how to adapt their behavior when relating to employees from other cultures and societies.

Our results also suggest which factors may be more important for generating empowerment among employees in accordance with the profession in which they work. Moreover, we have linked the inequality and gender stereotypes that exist in different professions with those variables that influence PE, which may have important practical implications. Providing more organizational support to healthcare and education workers, or focusing attention on leadership style in banking and industry, are two examples of recommended interventions.

According to Jocelyne and Kariuki (2020), empowerment initiatives or programs focused on the physical, mental, financial, and spiritual well-being of employees lead to a workplace in which people are motivated and possess a sense of purpose. Therefore, our results allow us to recommend interventions that enhance and improve the antecedents of EP. Examples include running training programs or courses for supervisors that promote transformational or authentic leadership styles, using high-performance managerial practices, improving support for workers by showing an interest in their well-being, ensuring adequate working conditions and ergonomics, and avoiding excessive demands and repetitive shift changes, among others.

Finally, the present meta-analysis may help encourage organizations to pay more attention to the antecedents and consequences of PE, focusing their efforts on improving or strengthening certain structures or factors. Almost a decade after the publication of Seibert et al.'s meta-analysis (2011), we are able to reaffirm and add new information to the model they proposed. As stated earlier, more longitudinal research is required to clarify whether the correlates of PE analyzed in the literature offer a causal explanation of the differences observed in empowerment levels, and underexplored areas such as organizational identification, job crafting, goal orientation and engagement also require further study.

In view of the above, managers should recognize the importance of adopting appropriate leadership styles, maintaining a suitable work environment, and offering workers greater access to support, resources, information, learning, innovation and growth, among other empowering actions.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Studies marked with an asterisk were included in the meta-analysis

Abra, J. (1989). Changes in creativity with age: Data, explanations, and further predictions. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 28(2), 105–126. https://doi.org/10.2190/E0YT-K1YQ-3T2T-Y3EQ

Ahmad, N., & Oranye, O. (2010). Empowerment, job satisfaction and organizational commitment: A comparative analysis of nurses working in Malaysia and England. Journal of Nursing Management, 18, 582–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01093.x

Aljarameez, F. (2019). The relationships of structural empowerment, psychological empowerment and organizational commitment in Saudi and non-Saudi registered staff nurses in Saudi Arabia [ProQuest Information & Learning]. In Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences (Vol. 81, Issue 5–A).