Abstract

This cross-sectional study investigated the relationships between the sense of coherence (SOC) and resilience and between distress and infection prevention behaviors during the early phase of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. The study recruited 1,484 participants (male: 686, female: 798; mean age = 45.1 years, SD = 8.3 years) to complete the SOC-L9 scale, the Adolescent Resilience Scale, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, and the measurement scale of practices of infection prevention behaviors against COVID-19, originally developed by the study in addition to other control variables. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis demonstrated that greater SOC was associated with less distress during the COVID-19 pandemic, even after resilience was controlled for. Additionally, logistic regression analysis revealed that greater resilience was associated with the majority of greater COVID-19 related infection prevention behaviors (IPBs). These results suggest that SOC and resilience were related to degree of distress during the COVID-19 pandemic, such that those with higher resilience tended to engage in IPB. Furthermore, differences in the association of both factors with distress and IPB may indicate a few points of discrimination between SOC and resilience, which include similar concepts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In response to the spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19), measures to prevent infection, such as avoidance of the three Cs (3Cs, that is, areas with poor ventilation, crowded areas, and settings where close-range conversations may occur) have been promoted in Japan and have become widely known (Hayasaki, 2020). After lifting the state of emergency at the end of May 2020, the country entered a transitional period in which restrictions on traveling and the use of facilities were gradually alleviated. The continued implementation of the aforementioned measures to prevent infectious diseases has become important in preventing the re-occurrence of infection. In other words, the degree to which each citizen thoroughly implements preventive behaviors against infectious diseases will greatly influence the future progression of the COVID-19 pandemic (Amsalem et al., 2021; Yonemitsu et al., 2020). In Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (2020a, b) has proposed “The New Lifestyle,” which includes the following prevention behaviors against COVID-19 that individuals can practice in daily life, such as mask-wearing, handwashing, and social distancing. The habitual practice of these infection-preventive behaviors is one of the most important measures for preventing the spread of infection and is being used as reminders and recommendations.

Such infection-prevention behaviors (IPBs) against COVID-19 are considered one of the main topics of studies on COVID-19 in the field of psychology. Brouard et al. (2020) suggested that psychological factors, such as anxiety about COVID-19 and perceived political ideology, promote IPBs, such as mask-wearing. In Japan, Yamagata et al. (2021) found that during the COVID-19 pandemic, there are more opportunities to routinely take IPBs different from normal conditions, and that such an increase in IPBs was associated not only with anxiety and risk perception toward COVID-19 but also with the fear of and aversion to physical or spiritual impurity with a gender difference. Furthermore, a review and meta-analysis of studies on the current state of COVID-19 related IPBs in various countries indicated that knowledge about COVID-19 promotes COVID-19 related IPBs, while fatigue and illness, anxiety, and stress, might inhibit COVID-19 related IPBs (Saadatjoo et al., 2021). Thus, identifying the psychosocial variables associated with IPBs, similar to the abovementioned studies, is a notable attempt at providing important insights when considering measures for promoting COVID-19 related IPBs. One of the important factors in determining an individual’s health-related behavior, including infection-prevention behavior, is psychological characteristics or personality traits. For example, previous scholars found a relationship between the “Big Five” personality traits and COVID-19 related IPBs among the general population; conscientiousness positively related to individual and social behaviors related to health and infection prevention, whereas extraversion negatively related to IPBs (e.g., Brouard et al., 2020; Carvalho et al., 2020). Other scholars report that conscientiousness is positively related to compliance with COVID-19 protection protocols, whereas extraversion is negatively related among the general population (Brouard et al., 2020). Thus, predicting COVID-19 related IPBs from the perspective of personality traits would render the identification of individuals and groups at high or low risk of COVID-19 possible. Therefore, examining the relationship between psychological characteristics and IPBs, specifically in Japan, is important.

The sense of coherence (SOC) is defined as an individual’s perception and the sense that their experiences in the world are coherent, comprehensible, consistent, and meaningful; those with high levels of SOC can cope effectively and flexibly with stressors in the theory of salutogenesis with SOC as a core concept (Antonovsky, 1987). SOC consists of three components: comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness (Antonovsky, 1987). Comprehensibility means that the stimuli encountered in the future will be predictable (Antonovsky, 1987). Manageability refers to the extent to which a person perceives that their resources are adequate to meet the demands (Antonovsky, 1987). Meaningfulness refers to the extent that stimuli are considered worth investing energy in, worthy of commitment, and challenges rather than burdens (Antonovsky, 1987). Moreover, SOC is a strong predictor of mental health or distress among personality traits (Flensborg-Madsen et al., 2005; Grevenstein & Bluemke, 2015) and is associated with the maintenance of mental health even under difficult circumstances (Hochwälder & Forsell, 2011). Simultaneously, it is one of the psychological characteristics reported to be associated with health-related behaviors. For example, individuals with high levels of SOC were more likely to engage in daily physical activities among students and adults (Kuuppelomäki & Utriainen, 2003; Suominen et al., 2005), brush their teeth frequently to maintain oral care conditions among the adults and older adults (Bernabé et al., 2012; Savolainen et al., 2005), and experience less alcohol-related problems among general population (Midanik et al., 1992; Antonovsky, 1987), who proposed the concept of SOC, explained that individuals with high levels of SOC do not simply prefer health-related behaviors; instead, they opt for health-related behaviors as the most effective coping resource (general resistance resources) because of an accurate understanding of their health problems. Given these findings, the study proposes that SOC would be negatively associated with distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, individuals with high levels of SOC would be more likely to engage in COVID-19 related IPBs, one of the coping resources for health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Furthermore, resilience is a factor with a theoretical similarity to SOC. Resilience is defined as a psychological trait enabling adaptation despite challenging or threatening circumstances that help people recover from distressFootnote 1 (Masten et al., 1990; Oshio et al., 2002). Resilience has been conceptualized and assessed somewhat differently in different studies. According to the definition by Oshio et al. (2002, 2003), those with high resilience are characterized by a high preference for new challenges, emotional control, and a positive outlook on the future. These elements are considered to constitute resilience as factors referred to as “novelty seeking,” “emotional regulation,” and “positive future orientation” (Oshio et al., 2002). The presence of the trait helps relieve the stress associated with negative events and promotes normal adaptive behavior, which, thus, has been associated with the prevention of distress (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005; Kukihara et al., 2014; Oshio et al., 2002). Such an orientation is included as comprehensibility in SOC (Antonovsky, 1987) and novelty seeking in resilience (Oshio et al., 2003) and is considered a characteristic that positively affects stress coping. Quantitative studies with the general population have shown that SOC and resilience have overlapping components, while, simultaneously, the two traits feature relatively different associations with external indicators (e.g., physical and distress, strategies for coping with stress, and well-being), where SOC was reported to exhibit better predictive utility, especially regarding health-related indicators (Grevenstein et al., 2016; Izydorczyk et al., 2019; Yoneda et al., 2018). The reason for these differences is that SOC includes psychological traits that promote perceptions and appraisals such as meaningfulness and manageability, which are motivations to find meaning in dealing with specific issues and actively engage in them, and thus may be more strongly related to health-related behaviors than it is to resilience, which focuses on adaptation to the current situation. Because of their conceptual similarity and because they are both characteristics associated with health-related behaviors, they are expected to be associated with COVID-19 related IPBs; however, due to the aforementioned conceptual differences, their associations with external indicators may be different. Accordingly, both factors should be considered in the context of their relationship with distress and COVID-19 related IPBs, and their similarities and differences should be elucidated.

The extant research highlights the importance of predicting individual prevention behaviors against infectious diseases, where resilience and SOC are candidate predictors. Because SOC and resilience include orientations that can be changed by social and environmental factors, they are both considered acquired and transformable traits, although relatively stable (Delbar & Benour, 2001; Ueno et al., 2019); thus, scholars have investigated interventions to improve resilience and SOC (e.g., Ando et al., 2011; Robertson et al., 2015). Therefore, if associations exist between SOC, resilience, and COVID-19 related IPBs then targeted interventions could be developed to address these psychological factors and thereby promote infection-prevention behavior while maintaining and improving distress. Accordingly, this study investigates the relationship between SOC, resilience, and COVID-19 related IPBs. In addition to these major factors, the study assesses the several control variables potentially related to COVID-19 related IPBs and psychological factors such as social attributes (gender, age, and residential area) and perceived vulnerability to disease (Duncan et al., 2009). Against this background, this study presents the following hypotheses:

-

H1: SOC and resilience can be used to predict lower distress during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

H2: SOC and resilience are positively associated with COVID-19 related IPBs.

Methods

Participants

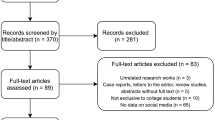

An online survey was conducted in June 2020. A total of 1,900 Japanese men and women (aged in their 30 to 50 s and members of the iBRIDGE Ltd. research registry) participated anonymously in the survey through Freeasy, a web research service provided by iBRIDGE Ltd. Data from 1,484 participants (male: 686; female: 798; mean age: 45.1 years, SD = 8.3 years) who correctly answered the Directed Questions Scale (DQS; Maniaci & Rogge 2014) were analyzed. The DQS was added to these questions to detect and screen out the participants who are not paying sufficient attention to answer the questions. Specifically, the item “Select ‘probably no’ for this item” was added to the questionnaire. Using DQS, participants who exhibit a satisfactory answering style in which a respondent does not intend to allocate attentional resources to the investigation, such as those who answer without carefully reading the question, were excluded (Maniaci & Rogge, 2014). Of the analyzed, 814 were university graduates. Additionally, there were 522 living in the specific alert prefectures.Footnote 2

Ethical considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants through an online survey. Data collection was conducted anonymously. The participants were assured that non-participation would not lead to any disadvantages. These ethical considerations were explained to potential participants via a text explanation at the interface of the survey. This study was conducted with approval from the ethics committee at the previous affiliation of the first author (approval number: 20–29).

Measurements

Measurement of psychological variables

SOC was measured using the Leipzig Short Scale of SOC (SOC-L9; Lin et al., 2019; Japanese version: Kase & Endo, 2020; Togari et al., 2015). SOC-L9 is composed of nine items (e.g., Do you have the feeling that you are in an unfamiliar situation and don’t know what to do?), which are rated using a seven-point Likert-type scale (e.g., 1 = very often; 7 = very seldom or never). High scores of SOC-L9 indicate high SOC levels. The SOC-L9 has been verified to have high validity, as its item fit and association with criterion-related indicators such as distress, anxiety, and depression have been verified (Lin et al., 2019; Kase & Endo, 2020).

Resilience was measured using the Adolescent Resilience Scale (Oshio et al., 2002, 2003). It has been reported that ARS is reliable and valid in quantitative studies on adults (Ueno et al., 2019). ARS is composed of 21 items (e.g., I am sure that good things will happen in the future), which are rated using a five-point Likert-type scale. High ARS scores indicate high levels of resilience. Although the ARS was developed based on data obtained from adolescents, its measurement follows the general definition of resilience (Nancy et al., 2006), and because it is a scale whose reliability and validity have been confirmed in multiple studies with college students (e.g., Nakaya et al., 2006; Oshio et al., 2003), we considered it suitable for use in this study.

As an outcome, distress was measured using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10; Kessler et al., 2002; Japanese version: Furukawa et al., 2008). K10 has ten items (e.g., During the past four weeks, how often did you feel tired out for no good reason?), which are rated using a five-point Likert-type scale. Although K10 has a cutoff value for determining the presence or absence of mental disorders, whether this cutoff value functions relatively well under other conditions is unclear because this study was conducted under the specific stress conditions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic (Okubo, 2021). Therefore, we decided to use the scores for K10 as a continuous variable for analysis. High K10 scores highly indicate distress. The K10 has been associated with measures of mental health and distress, such as the University Personality Inventory and the General Health Questionnaire, and it is validated (Sakai & Noguchi, 2015).

In addition to these measurement scales, the study used the Perceived Vulnerability to Disease Scale (PVD: Duncan et al., 2009; Japanese version: Fukukawa et al., 2014) to measure psychological fear and anxiety about infectious diseases in general (as opposed to COVID-19 specifically) as the control variable. PVD considers two theoretical factors, namely, perceived infectability (Generally, I am very susceptible to colds, flu, and other infectious diseases; seven items) and germ aversion (I prefer to wash my hands soon after shaking someone’s hand; eight items). It is composed of 15 items rated using a seven-point Likert-type scale. High PVD scores indicate high fear and anxiety regarding infectious diseases. PVD has theoretically valid correlates with psychosomatic tendencies and personality traits (Fukukawa et al., 2014).

Measurement of COVID-19 related IPBs

Based mainly on “The New Lifestyle” practices presented by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2020a, b), the study collected data on COVID-19 related IPBs for measurement concerning information made available to the public for June 2020. In May 2020, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (2020a, b) proposed a new, unified preventive action plan for COVID-19 in Japan under the title of The New Lifestyle, and the following June, the expert panel further organized and published the information. Thus, the survey was conducted during this period because it was deemed the time at which a common understanding of preventive behavior was formed in Japan.

After repeated discussions among the researchers to ensure the absence of bias or overlap in the content, 14 types of behaviors were selected for measurement, and questions were prepared (Table 1). The survey is composed of 14 items rated using an 11-point scale from 0 (not at all applicable) to 10 (very applicable) based on the response method used by Brouard et al. (2020). In this manner, the study aimed to determine the extent to which the participants performed COVID-19 related IPBs in the previous three months. Additionally, concerning Brouard et al. (2020) and Firouzbakht et al. (2021), we used dummy variables that indicate values above or below the median value of each item (0: a lower level of practicing the COVID-19 related IPBs; 1: a higher level of practicing COVID-19 related IPBs) in the data analysis, to compare the degree of association of independent variables to levels of practicing by odds ratios.

Confounding variables

Demographic variables consisted of gender (female = 1; male = 0), age, residential area (specific alert prefectures = 1, others = 0), and level of education (university graduates = 1, undergraduates = 0). For the residential area, we asked the respondents to specify their place of residence among the 47 prefectures in Japan. Thereafter, a dummy variable was used to discriminate whether the respondents lived in the 13 areas referred to as “specific alert prefectures” by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (2020a, b), where the spread of COVID-19 was significant, and special behavioral restrictions were requested in May 2020.

Data analysis

First, basic analysis was performed, such as the calculation of descriptive statistics, the reliability coefficients for each scale, and the correlation coefficients among variables. Next, multiple regression analysis was conducted using the scores for K10 as the dependent variable; scores for SOC and resilience as the independent variables; and sociodemographic variables and scores for PVD as the control variables. Afterward, logistic regression analysis was conducted using the scores for COVID-19 related IPBs, which were made into dummy variables, as the dependent variables, scores for SOC and resilience as the independent variables, and sociodemographic variables and scores for PVD as the control variables. In the series of logistic analyses, each COVID-19 related IPB item was analyzed separately. Significance levels were adjusted for the number of multiple tests per analysis. Adjusted critical p-values were p < .01 for the analysis for K10 scores and p < .004 for IPBs scores.

Statistical analyses were conducted using HAD version 17.204 (Shimizu, 2016) and R version 4.1.0 (R Development Core Team, 2022).

Results

Basic analysis

Table 2 provides the mean value, standard deviation, and reliability coefficients of each scale. For the IPBs scores, the frequency distribution was skewed in the negative direction, and based on the test of normality, it could be determined that the normality did not hold up to the parametric test; hence, it was decided to make it a dummy variable as planned. Reliability coefficients were above.70 for all scales, which indicates the absence of problems with internal consistency per scale. Additionally, a significant positive correlation coefficient was obtained between the scores for SOC-L9 and ARS (r = .75, p = .00). These had significant negative correlation coefficients with K10 or the scores for the two sub-scales of PVD (r = − .07 to − 0.68, ps = 0.00 to 0.04), respectively. Additionally, descriptive statistics of IPBs were calculated, and the distribution of dummy variables was confirmed.

Relationship with distress

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis using the scores for K10 as the dependent variable indicated that R2 and ΔR2 were significant in Step 3 with all control and independent variables included (Table 3; R2 = 0.48, p = .00; ΔR2 = 0.17, p = .00). The standardized partial regression coefficient of scores from ARS to K10, which was significant in Step 2 (β = −0.46, p = 00), was no longer significant in Step 3 (β = 0.00; p = .90). Instead, a significant standardized partial regression coefficient from the score for SOC-L9 was found (β = −0.64, p = .00).

Relationship with IPBs

Logistic regression analysis using the dummy variables of the COVID-19 related IPBs as the dependent variables illustrated that resilience was significantly associated with 12 of the 14 items (OR = 1.41 to 2.21, ps = 0.00 to 0.01. see Table 4). SOC was non-significantly associated. The variance inflation factors are all less than 3.

Contrary to the hypothesis, no significant association was noted between SOC to most of the COVID-19 related IPBs. Thus, we conducted exploratory analyses excluding resilience from the model predicting COVID-19 related IPBs. The result pointed to significant associations of SOC with all items, except for Q2 and Q8 (OR = 1.14 and 1.40, ps = 0.00 to 0.08; McKelvey and Zavoina Pseudo R2 = 0.05 to.17).

Discussion

General discussion

This study examined the association of SOC and resilience with distress and the COVID-19 related IPBs. First, the results of multiple regression analysis indicated that SOC predicted distress during the COVID-19 pandemic even after controlling for resilience. The results supported those of previous studies that reported the greater predictive utility of SOC than that of resilience for health-related indicators such as psychological well-being and depression tendency (e.g., Izydorczyk et al., 2019; Yoneda et al., 2018). The value of the correlation coefficient between SOC and resilience was.75 (p < .01), which indicates a high positive correlation between them. Previous studies on SOC and resilience observed that the values of correlation coefficients ranged from 0.35 (p < .01; Nygren et al., 2005) to 0.69 (p < .01; Keil et al., 2017). Many scales can be used to measure resilience (e.g., Connor & Davidson, 2003; Friborg et al., 2003; Wagnild & Young, 1993), and they can be used differently according to the theoretical definition of resilience. The current study viewed resilience as an intra-individual factor and used the ARS, which is a suitable scale of measurement for this definition. Therefore, a possibility exists that some aspects of the construct of resilience overlap with some aspects of SOC. However, the value of the incremental explained variance in Step 3 of hierarchical multiple regression analysis (ΔR2 = 0.17, p = .00) may indicate discrimination between SOC and resilience in their relationship with distress.

In contrast, resilience was positively associated with many COVID-19 related IPBs. Simply put, the study suggests that individuals with high levels of resilience tend to be more likely to report practicing COVID-19 related IPBs. For SOC, the results indicated no significant association when resilience was considered. Health-related behaviors that were associated with SOC in previous studies were mainly those that maintain and improve health as daily habits, such as physical activity (Kuuppelomäki & Utriainen, 2003; Suominen et al., 2005) and oral care (Bernabé et al., 2012; Savolainen et al., 2005). Compared to such health-related behaviors, COVID-19 related IPBs are construed as their facet as socially required by government agencies and workplaces out of consideration for others and can be regarded to possess characteristics that differ from those of habitual behavior voluntarily performed toward maintaining and improving health (Nakayauchi et al., 2021; Sakakibara & Ozono, 2021). According to the prototypes of personality, which is a classification of personality characteristics based on the Big Five personality traits, individuals classified as Resilients (those with the highest levels of resilience) are characterized by their tendency to engage in prosocial behavior (Asendorpf et al., 2001; Herzberg & Roth, 2006; Elliott et al., 2017). Furthermore, scholars suggested that resilience is positively correlated with social desirability in terms of measurement indices (Wagnild, 2009). Based on these facts, we infer that persons with high levels of resilience are more likely to practice IPBs against the COVID-19 pandemic as desirable actions required of and by society. Against these tendencies, resilience was not significantly associated with the behaviors of going out and avoiding eating out. Resilience features an aspect called novelty seeking, which refers to an interest in new events and willingness to take on new challenges (Oshio et al., 2003), and was reported to be positively correlated with the Big Five personality traits of extraversion and openness (Nakaya et al., 2006). Going out and eating out tend to satisfy novelty seeking; the study inferred that they are not associated with the avoidance of these behaviors. Alternatively, the only behavior found related to SOC was whether health information was collected through social networking services. The result indicates that those with high levels of SOC tended to be less likely to engage in such behavior. A characteristic of people with high levels of SOC is an attitude of systematically selecting and organizing information (Antonovsky, 1987; Kase et al., 2016). Thus, we inferred that they do not use SNS as an information resource on COVID-19 due to this attitude and the large amount of information that exists in an unregulated manner, which renders determining their authenticity difficult.

Limitations and directions for future research

In summary, the results suggest that SOC and resilience have been negatively associated with distress during the early phase of COVID-19 pandemic; those with higher SOC and resilience tended to have lower distress. Moreover, resilience was positively related with COVID-19 related IPBs, and individuals with higher resilience tended to engage in IPBs. In addition, there is no association with SOC and IPBs in relationship with resilience. This study only examined the relationship between psychological variables and behavioral indicators using cross-sectional data based on self-assessment; however, it does not support a causal interpretation regarding the relationships among these variables. This study also focuses on the early pandemic experience and does not provide information on changes in distress or IPBs during the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, the results may indicate different trends from the present situation. Furthermore, in this study, the survey was conducted to coincide with the release of The New Lifestyle, a set of standards for infection-prevention behavior in Japan, and by asking survey participants to recall their behavior during the three months from March to June 2020, we could obtain a self-assessment of their average commitment to preventive behavior immediately after the outbreak. The survey was conducted to collect data regarding these three months. However, the assumption of three months may lead to a recall bias in the self-evaluation of efforts exerted toward preventive behavior, depending on factors, such as whether they had experienced infection and whether they had close relatives who had been infected. In addition, responses for the survey may have been affected by unaware changes in preventive behaviors over the course of the months. In the future, it may be possible to collect less-biased data, by having the participants describe the most recent activities, such as one week or asking them to respond to the frequency of the action using an experience sampling method. Additionally, identifying the temporal relationship between COVID-19 related IPBs and psychological characteristics using a longitudinal study that considers perceived COVID-19 risk, comorbidities, level of disruption caused by the pandemic, and changes in the state of epidemics of infectious diseases is necessary to elucidate the effects of SOC and resilience on COVID-19 related IPBs.

Furthermore, differences in the association of both factors with distress and COVID-19 related IPBs may indicate discrimination between SOC and resilience, which include similar concepts. However, additional research is required to further examine the discriminant validity of SOC and resilience, and their differential associations with other variables such as social desirability and prosocial behaviors. Thus, elaborating on statistical and theoretical similarities and discrimination between SOC and resilience will be necessary by considering prosocial behavior, social desirability, and variables considered overlapping with SOC and resilience (e.g., emotional well-being) in future studies. In this study, we used a scale for adolescents to measure resilience; however, there is also a need to use a validated scale for adults in the future to increase the interpretability of the results.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

Specific alert prefectures: prefectures requested by the government to restrict activities due to the high percentage of positive cases of COVID-19: Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, Chiba, Osaka, Hyogo, Fukuoka, Hokkaido, Ibaraki, Ishikawa, Gifu, Aichi, and Kyoto.

References

Amsalem, D., Dixon, L. B., & Neria, Y. (2021). The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak and mental health: current risks and recommended actions. JAMA Psychiatry, 78, 9–10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1730

Ando, M., Natsume, T., Kukihara, H., Shibata, H., & Ito, S. (2011). Efficacy of mindfulness-based meditation therapy on the sense of coherence and mental health of nurses. Health, 3, 118–122. https://doi.org/10.4236/health.2011.32022

Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unravelling the mystery of health: how people manage stress and stay well. Jossey-Bass.

Asendorpf, J. B., Borkenau, P., Ostendorf, F., & Van Aken, M. A. G. (2001). Carving personality description at its joints: confirmation of three replicable personality prototypes for both children and adults. European Journal of Personality, 15, 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.408

Bernabé, E., Newton, J. T., Uutela, A., Aromaa, A., & Suominen, A. L. (2012). Sense of coherence and four-year caries incidence in finnish adults. Caries Research, 46, 523–529. https://doi.org/10.1159/000341219

Brouard, S., Vasilopoulos, P., & Becher, M. (2020). Sociodemographic and psychological correlates of compliance with the COVID-19 public health measures in France. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne de Science Politique, 53, 253–258. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423920000335

Carvalho, L. D. F., Pianowski, G., & Gonçalves, A. P. (2020). Personality differences and COVID-19: are extroversion and conscientiousness personality traits associated with engagement with containment measures? Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 42, 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2020-0029

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

Delbar, V., & Benor, D. E. (2001). Impact of nursing intervention on cancer patients’ ability to cope. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 19, 57–75. https://doi.org/10.1300/J077v19n02_04

Duncan, L. A., Schaller, M., & Park, J. H. (2009). Perceived vulnerability to disease: development and validation of a 15-item self-report instrument. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 541–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.05.001

Elliott, T. R., Hsiao, Y. Y., Kimbrel, N. A., Meyer, E., DeBeer, B. B., Gulliver, S. B., Kwok, O. M., & Morissette, S. B. (2017). Resilience and traumatic brain injury among Iraq/Afghanistan war veterans: differential patterns of adjustment and quality of life. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73, 1160–1178. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22414

Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399–419. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357

Firouzbakht, M., Omidvar, S., Firouzbakht, S., & Asadi-Amoli, A. (2021). COVID-19 preventive behaviors and influencing factors in the iranian population: a web-based survey. BMC Public Health, 21, 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10201-4

Flensborg-Madsen, T., Ventegodt, S., & Merrick, J. (2005). Sense of coherence and physical health. A review of previous findings. The Scientific World Journal, 5, 665–673. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2005.85

Friborg, O., Hjemdal, O., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Martinussen, M. (2003). A new rating scale for adult resilience: what are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 12, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.143

Fukukawa, Y., Oda, R., Usami, H., & Kawahito, J. (2014). Development of a Japanese version of the perceived vulnerability to disease scale. The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 85, 188–195. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.85.13206

Furukawa, T. A., Kawakami, N., Saitoh, M., Ono, Y., Nakane, Y., Nakamura, Y., Tachimori, H., Iwata, N., Uda, H., Nakane, H., Watanabe, M., Naganuma, Y., Hata, Y., Kobayashi, M., Miyake, Y., Takeshima, T., & Kikkawa, T. (2008). The performance of the japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the world mental health survey Japan. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 17, 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.257

Grevenstein, D., & Bluemke, M. (2015). Can the big five explain the criterion validity of a sense of coherence for mental health, life satisfaction, and personal distress? Personality and Individual Differences, 77, 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.053

Grevenstein, D., Aguilar-Raab, C., Schweitzer, J., & Bluemke, M. (2016). Through the tunnel, to the light: why sense of coherence covers and exceeds resilience, optimism, and self-compassion. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.001

Grotberg, E. H. (1995). A guide to promoting resilience in children: strengthening the human spirit. Early childhood development: practice and reflections, 8. Bernard van Leer Foundation.

Hayasaki, E. (2020). Covid-19: how Japan squandered its early jump on the pandemic. The British Medical Journal, 369, m1625. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1625

Herzberg, P. Y., & Roth, M. (2006). Beyond resilients, undercontrollers, and overcontrollers? An extension of personality prototype research. European Journal of Personality, 20, 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.557

Hochwälder, J., & Forsell, Y. (2011). Is sense of coherence lowered by negative life events? Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 475–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9211-0

Izydorczyk, B., Sitnik-Warchulska, K., Kühn-Dymecka, A., & Lizińczyk, S. (2019). Resilience, sense of coherence, and coping with stress as predictors of psychological well-being in the course of schizophrenia: the study design. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071266

Kase, T., & Endo, S. (2020). Reliability and construct validity of the Leipzig short scale of sense of coherence (SOC-L9) in japanese sample: the Rasch measurement model and confirmatory factor analysis. The Japanese Journal of Personality, 29, 120–122. https://doi.org/10.2132/personality.29.2.11

Kase, T., Ueno, Y., & Oishi, K. (2016). Features and the structure of life skills in persons with high levels of sense of coherence. The Japanese Journal of Personality, 25, 93–96. (In Japanese with English abstract). https://doi.org/10.2132/personality.25.93

Keil, D. C., Vaske, I., Kenn, K., Rief, W., & Stenzel, N. M. (2017). With the strength to carry on. Chronic Respiratory Disease, 14, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1479972316654286

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32, 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291702006074

Kukihara, H., Yamawaki, N., Uchiyama, K., Arai, S., & Horikawa, E. (2014). Trauma, depression, and resilience of earthquake/tsunami/nuclear disaster survivors of Hirono, Fukushima, Japan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 68, 524–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12159

Kuuppelomäki, M., & Utriainen, P. (2003). A 3-year follow-up study of health care students’ sense of coherence and related smoking, drinking and physical exercise factors. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 40, 383–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7489(02)00103-7

Lin, M., Bieda, A., & Margraf, J. (2019). Short form of the sense of coherence scale (SOC-L9) in the US, Germany, and Russia. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 36, 796–804. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000561

Maniaci, M. R., & Rogge, R. D. (2014). Caring about carelessness: participant inattention and its facts on research. Journal of Research in Personality, 48, 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.09.008

Masten, A. S., Best, K. M., & Garmezy, N. (1990). Resilience and development: contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology, 2, 425–444. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400005812

Midanik, L. T., Soghikian, K., Ransom, L. J., & Polen, M. R. (1992). Alcohol problems and sense of coherence among older adults. Social Science and Medicine, 34, 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(92)90065-X

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. (2020a). Information about the new coronavirus infections. (In Japanese) Retrieved from https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000164708_00001.html. Accessed 10 May 2022.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (2020b). New coronavirus infections: report on the implementation of the declaration of a state of emergency. (In Japanese) Retrieved from https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000121431_newlifestyle.html. Accessed 10 May 2022.

Nakaya, M., Oshio, A., & Kaneko, H. (2006). Correlations for adolescent resilience scale with big five personality traits. Psychological Reports, 98, 927–930. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.98.3.927-930

Nakayauchi, K., Ozaki, T., Shibata, Y., & Yokoi, R. (2021). Determinants of hand-washing behavior during the infectious phase of COVID-19. The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 92, 327–331. (In Japanese with English abstract). https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.92.20314

Nancy, R. A., Ermalynn, M. K., Mary, L. S., & Jacqueline, B. (2006). A review of instruments measuring resilience. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 29, 103–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/01460860600677643

Nygren, B., Aléx, L., Jonsén, E., Gustafson, Y., Norberg, A., & Lundman, B. (2005). Resilience, sense of coherence, purpose in life and self-transcendence in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old. Aging and Mental Health, 9, 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360500114415

Okubo, T. (2021). Infectious disease control or economic measures?: what do the public think of the current state of corona control? Nira Opinion Paper, 56, 1–10. (In Japanese). https://doi.org/10.50878/niraopinion.56

Oshio, A., Kaneko, H., Nagamine, S., & Nakaya, M. (2003). Construct validity of the adolescent resilience scale. Psychological Reports, 93, 1217–1222. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2003.93.3f.1217

Oshio, A., Nakaya, M., Kaneko, K., & Nagamine, S. (2002). Psychological characteristics leading to recovery from negative events: development of the resilience scale. Japanese Journal of Counseling Science, 35, 57–65. (In Japanese).

R Development Core Team (2022). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. http://www.R-project.org/ Accessed 10 May 2022.

Robertson, I. T., Cooper, C. L., Sarkar, M., & Curran, T. (2015). Resilience training in the workplace from 2003 to 2014: a systematic review. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88, 533–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12120

Saadatjoo, S., Miri, M., Hassanipour, S., Ameri, H., & Arab-Zozani, M. (2021). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the general population about Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis with policy recommendations. Public Health, 194, 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.03.005

Sakai, W., & Noguchi, H. (2015). Comparison of tests of mental health for student counseling: formation of a common measure. The Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology, 63, 111–120. (In Japanese with English abstract). https://doi.org/10.5926/jjep.63.111

Sakakibara, R., & Ozono, H. (2021). Why do people wear a mask?: a replication of previous studies and examination of two research questions in a Japanese sample. The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 92, 332–338. (In Japanese with English abstract). https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.92.20323

Savolainen, J., Suominen-Taipale, A. L., Hausen, H., Harju, P., Uutela, A., Martelin, T., & Knuuttila, M. (2005). Sense of coherence as a determinant of the oral health-related quality of life: a national study in finnish adults. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 113, 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0722.2005.00201.x

Shimizu, H. (2016). An introduction to the statistical free software HAD: suggestions to improve teaching, learning and practice data analysis. Journal of Media Information and Communication, 1, 59–73. (In Japanese with English abstract).

Suominen, S., Gould, R., Ahvenainen, J., Vahtera, J., Uutela, A., & Koskenvuo, M. (2005). Sense of coherence and disability pensions. A nationwide, register-based prospective population study of 2196 adult Finns. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59, 455–459. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.019414

Togari, T., Yamazaki, Y., Nakayama, K., Yokoyama, Y., Yonekura, Y., & Takeuchi, T. (2015). Nationally representative score of the Japanese language version of the 13-item 7-point sense of coherence scale. Japanese Journal of Public Health, 62, 232–237. (In Japanese with English abstract). https://doi.org/10.11236/jph.62.5_232

Ueno, Y., Hirano, M., & Oshio, A. (2019). A reinvestigation of the age difference in resilience in a large cross-sectional Japanese sample. The Japanese Journal of Personality, 28, 91–94. (In Japanese with English abstract). https://doi.org/10.2132/personality.28.1.10

Wagnild, G. (2009). A review of the resilience scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 17, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.17.2.105

Wagnild, G. M., & Young, H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1, 165–178.

Yamagata, M., Teraguchi, T., & Miura, A. (2021). Japanese society and psychology during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study based on a survey in late March 2020. The Japanese Journal of Psychology, 92, 452–462. (In Japanese with English abstract). https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.92.20222

Yoneda, T., Kodama, S., Ando, Y., Ogawa, K., & Shito, K. (2018). Quantitative research of similarities and differences between sense of coherence and resilience. Journal of the Faculty of Nursing and Welfare Medical University of Hokkaido, 14, 59–64. (In Japanese).

Yonemitsu, F., Ikeda, A., Yoshimura, N., Takashima, K., Mori, Y., Sasaki, K., Qian, K., & Yamada, Y. (2020). Warning “Don’t spread” versus “Don’t be a spreader” to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic. Royal Society Open Science, 7, 200793. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.200793

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (grant numbers: 17K13149 and 19K14393).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study was conducted with approval (approval number: 20–29) from the ethics committee at Rikkyo University (the previous affiliation of the first author).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants through the online survey. Data collection was conducted anonymously. The participants were assured that non-participation will not lead to any disadvantages. These ethical considerations were explained to potential participants via a text explanation on the interface of the survey.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kase, T., Ueno, Y. & Endo, S. Association of sense of coherence and resilience with distress and infection prevention behaviors during the coronavirus disease pandemic. Curr Psychol 43, 707–716 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04359-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04359-w