Abstract

Status stability, which refers to the stability of team members’ relative status levels, has a profound effect on team effectiveness, but this effect may be either constructive or destructive; the literature has failed to reach consensus on this topic. To reconcile two contradictory views based on differentiating between different types of conflict, we constructed a comprehensive theoretical model of the mechanism underlying the effect of status stability; this model features relationship conflict and task conflict as mediators, status legitimacy as a moderator, and team creativity as an outcome variable. We also proposed four hypotheses on the basis of theoretical analysis. In this study, we used SPSS 23.0, AMOS 24.0 and R software to conduct empirical analysis and testing of 369 valid questionnaires collected from 83 teams using a two-stage measurement method. The results revealed that status stability negatively affects team creativity via task conflict and positively affects team creativity via relationship conflict. However, under the influence of status legitimacy, the negative effect is restrained, while the positive effect is enhanced. This study thus expands the research on the process mechanism and boundary conditions associated with status stability, and can serve as a useful reference for the design of the status structure of modern enterprises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Creativity guarantees the team competitiveness in a dynamic environment (Pillay et al., 2020), and the task of stimulating team creativity has always been an important issue for scholars and organizational managers. Studies have shown that team creativity requires not only the input of individual resources by team members but also the interaction and collaboration among them to promote the full flow and effective integration of these individual resources within the team (Aggarwal & Woolley, 2019). However, status resources differ from ordinary resources since they are highly incentivized and competitive (Pearce, 2011; Kemper, 2016), and are related to the interests of team members. Therefore, status stability inevitably affects the resource input and interaction behavior of team members. If the setting of status stability in the team is unreasonable, this situation affects the incentivizing effect of status on team members, which may cause team members to lose their enthusiasm for work and may also cause them to engage in conflicts due to their competition for status, thus leading to the destruction of team members’ resource input and cooperative interaction behavior and hindering the improvement of team creativity.

Status stability refers to the degree of stability of the relative status of group members (Aime et al., 2014), as well as the timeliness and difficulty of status transformation among team members (van Dijk & van Engen, 2013). With regard to the source of such status, status stability includes formal status stability and informal status stability. The acquisition of informal status is based on reputation, influence, and respect. Informal status is not formally provided by the organization and may not change over a certain period of time in cases of strong stability. Formal status is based on rank, grade and job title, which can be adjusted over a certain period of time. Therefore, the status stability studied in this paper refers specifically to formal status stability. Previous studies on team creativity have adopted the notion of a stable status hierarchy as a default hypothesis (Bunderson & Boumgarden, 2010; Lee et al., 2018). Obviously, this default hypothesis lacks ecological validity and cannot truly describe the social structures underlying the relationship among team members. Simultaneously, in studies of organizational hierarchy, such as those pertaining to power disparity, status stability has also received extensive attention; however, most such studies focus have focused only on its moderating effect, such as the relationship between group status and intergroup attributes (Bettencourt, Dorr, Charlton, & Hume, 2001), status configuration and group performance (van Dijk & van Engen, 2013), group-based shame and ingroup favoritism (Shepherd et al., 2013), status differences and intergroup relationship (Saguy & Dovidio, 2013), group status and knowledge sharing behavior (Hu & Xie, 2015), self-performance expectations and promotion focus motivation (Hossain et al., 2020) and have neglected its main effect. As one of the important team characteristics, status stability will inevitably have a direct effect on team results, and is called for more attention (Chang et al., 2019).

According to the limited information found in studies on related topics, status stability has a “double-edged sword” effect on team effectiveness. One such effect is based on the constructive view of status functionalism, which posits that status stability can benefit teams by establishing a clear role and a stable collaborative order for teams, thus reducing the power struggle and conflicts that occur among members and improving the internal cooperation of the team (Halevy et al., 2011; Anderson & Brown, 2010; Van Bunderen et al., 2018). Another effect is focused on the destructive view of status conflict theory, which claims that status stability can hurt teams by limiting information sharing, weakening the incentive function of hierarchy, and reducing the enthusiasm of team members to participate in discussions (Gray & Ariss, 1985; Bidwell, 2013; Halevy et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2019). Therefore, with regard to team creativity, is status stability constructive or destructive? Obviously, these inconsistent views emphasize the need to construct a more systematic theoretical model of the effect of status stability on team creativity that can integrate these two different mechanisms to comprehensively explore the mechanism underlying the effect of status stability on team creativity and to promote the effective allocation of status in the process of team innovation.

Status characteristics generally do not affect team results directly, but interact with team processes to affect team results (Anderson & Brown, 2010). Process mechanism research is thus important for understanding the mechanism underlying the effects of status stability. A review of previous literature reveals that team conflict is an important process variable in this context, that hierarchy (including power and status) affects team results, and that the reduction of team conflict is a prerequisite for achieving team collaboration and ultimately improving team results (Tarakci et al., 2016; Van Bunderen et al., 2018; Greer et al., 2018). Chang et al. (2019) also noted in their research that team conflict is key to explaining differences in the utility of status stability. However, most of these studies have regarded team conflict exclusively as a single-dimensional variable, ignoring the facts that team conflict includes different types of conflict and that these different types of conflict have different effects on team performance (Simons & Peterson, 2000; Zhu et al., 2019). Obviously, this approach may only verify the single effect of team conflict and may confuse the different effects of different types of conflict. Therefore, when team conflict is divided into different types of conflict, is the effect of status stability on team results consistent across different types of conflict paths? This question has not been answered by previous research. For this reason, some scholars have suggested that different types of conflict should be distinguished from one another and that the mediating role of different types of conflict between status stability and team performance should be discussed (Chang et al., 2019). Therefore, based on the extant literature, this study divides conflict into relationship conflict and task conflict (Jehn, 1995) and uses empirical research methods to explore the ways in which status stability affects team performance with regard to different paths of relationship conflict and task conflict to fully reveal the process mechanism by which status stability affects team performance.

The ultimate orientation of status stability, i.e., whether it is constructive or destructive, depends on the specific organizational context in question (Chang et al., 2019; Aime et al., 2014). Hitherto, research on the organizational context of the role of status stability has been less involved, and this topic thus requires further exploration. According to previous studies, there is a complex interaction between status stability and status legitimacy (Saguy & Dovidio, 2013), and this interaction affects the behavior and psychology of group members, group processes and group performance (van Dijk & van Engen, 2013; Halabi et al., 2014). Status stability and status legitimacy are also inseparable; for example, an unstable group social division system is more likely to be regarded as illegitimate, while a system that is regarded as illegitimate tends to contain unstable seeds (Tajfel, 1981). These factors jointly determine how members with different levels of status within a group compare socially (Bettencourt et al., 2001). As an important status-related feature, the degree of status legitimacy affects the interaction behavior and interpersonal relationships of group members (Dijk, 2013). Status legitimacy is defined as “a status hierarchy that is considered appropriate, correct, and just, and that legitimate status is normatively conferred on the basis of characteristics such as competence, leadership, and team orientation” (Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Hays, 2013). When group members are aware of the legitimacy of such status, they believe that the allocation of status resources is reasonable; thus, they accept and identify with the group and the existing status situation, and they are more obedient to authority (Bettencourt & Bartholow, 1998; Li et al., 2020), which is conducive to reducing the competition and conflict caused by unstable status and promoting cooperation within the team. Once they realize that their status is illegitimate, group members, especially low-status members, tend to exhibit increased perceptions of unfairness and thus to raise objections to their own status and attempt to change the existing unreasonable structure (Bitektine, 2011; Brandt et al., 2020), inevitably leading to a further escalation of group conflict. It can thus be seen that the role of status stability may be affected by status legitimacy. Accordingly, this study aims to test in further detail whether the constructive effects of status stability on team creativity can be promoted and the corresponding destructive effects can be mitigated under the influence of status legitimacy from the perspective of empirical research.

Literature review and research hypotheses

Status stability, relationship conflict and team creativity

Relationship conflict refers to the opposition and disharmony of interpersonal relationships among team members, including anxiety, anger, disgust and other emotional components (Jehn, 1995). As an important status-related characteristic, status stability affects team members’ psychological perceptions and behavioral choices, thus affecting their interpersonal relationships within the team (Anderson & Kennedy, 2012; Anicich et al., 2016) as well as, ultimately, team creativity. Specifically, in cases of low status stability, team members tend to make self-interested and competitive choices due to their need to seek or maintain status, thus leading to competitive retaliation and the deterioration of interpersonal relationships (Hays & Bendersky, 2015). Concomitantly, when status stability is low, the psychological insecurity and vigilance of team members tends to be strengthened, and the resulting vigilance reduces mutual trust among members, increases suspicion and misunderstanding, and can easily lead to interpersonal tension (Anderson & Kennedy, 2012; Chang, pei, 2022). In addition, van Dijk and van Engen (2013) noted that when the status stability is low, team members actively pursue status promotion by using strategies such as independent decision-making or refusing to give approval when others are right, and these status promotion strategies cause dissatisfaction on the part of other members and can affect the interpersonal relationships among members. Contradictory interpersonal relationships cause team members to attribute other people’s differing views and solutions to problems to reasons associated with interpersonal conflict and to resist other people’s suggestions, particularly critical suggestions (Jung & Lee, 2015), which is naturally not conducive to the improvement of the team’s creative output. Due to the accompanying reduction in interpersonal conflict, negative emotions such as hostility within the team decrease, interpersonal trust increases (Lau & Cobb, 2010), and personal willingness to share and contribute knowledge increases (Shin et al., 2022), which is naturally helpful with respect to enhancing cooperation among team members and team creativity. Based on this analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1 (H1)

Relationship conflict mediates the relationship between status stability and team creativity.

Status stability, task conflict and team creativity

Task conflict refers to the differences in the team members’ opinions or viewpoints on the content and solution approach of the team task (Jehn, 1995). It is closely related to the team task. Status stability can affect team creativity not only through the process path of relationship conflict, but also through that of task conflict. Specifically, when status stability is high, in addition to providing clear roles and relationships, a stable cooperative order and other functions to the group, this situation also leads to the establishment of an excessively comfortable group atmosphere, which is not conducive to group members’ ability to propose their own views and hypotheses concerning task completion (Chang et al., 2019). Simultaneously, this situation also reduces the willingness of team members to share information as well as the frequency and quality of normal communication among team members, and it restricts the flow and sharing of resource information within the team (Gray & Ariss, 1985; O’Toole et al., 2002). In addition, high status stability restrains the level of task conflict by weakening the incentive function of hierarchy and reducing the motivation and productive behavior of team members (Halevy et al., 2011). High status stability thus reduces the level of task conflict within the team. This reduction in the level of task conflict inevitably leads to the weakening of internal interactions within the team with regard to tasks as well as of the understanding and insight of team members regarding each other’s views (Farh et al., 2010), which can not only motivate team members to actively give advice to seek to stand out on the team but also encourage team members to participate in task discussion more actively and share information resources in order to avoid elimination by the team. Low status stability also entails that the team status blockade is weakened (Bidwell, 2013), which can not only motivate team members, so that team members can actively give advice in order to seek to stand out in the team; it can also warn the team to participate in task discussion more actively and share information resources in order not to be eliminated by the team. Low status stability also means that the team status blockade is weakened (Bidwell, 2013). Team members in this situation are more flexible, less risk averse, and more daring with regard to taking risks. The information processing process in which they engage is more comprehensive, and the flows of knowledge from top to bottom and from bottom to top are greater (Sligte, De Dreu, & Nijstad, 2011). The improvement of information flow and sharing inevitably lead to an improvement in task conflict (Luo et al., 2020). Due to this improvement in task conflict, team members obtain a deeper understanding of each other’s abilities and personality characteristics, exhibit a higher degree of trust within the team, and have a deeper understanding of the task background and goals. Team members also have a higher frequency of interaction, so information exchange becomes smoother, and team members’ willingness to engage in knowledge-sharing behavior becomes more prominent (Lee et al., 2018). This situation helps the team generate more new ideas and enhances team creativity. Based on this analysis, this paper proposes the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2 (H2)

Task conflict mediates the relationship between status stability and team creativity.

The moderating effect of status legitimacy

Status legitimacy is a concept that effectively combines legitimacy with status hierarchy. Status legitimacy indicates that the status hierarchy structure is considered to be appropriate, correct and just, and legitimate status is granted based on competency, leadership, group orientation and other characteristics; generally, members with the greatest competency, leadership and group orientation have the highest status (Hays, 2013). Status legitimacy reflects the extent to which group members agree with each member’s status and thus accept the existing status configuration. The more group members believe that a certain member is competent with regard to the task at hand, the higher the status of that member becomes (van Dijk & van Engen, 2013; Kilduff et al., 2016) divided status legitimacy into two dimensions: validity and endorsement. Validity refers to the extent to which “the elements of a social order are seen as consistent with norms, values, and beliefs that individuals present are widely shared”. Endorsement refers to the appropriate support of peers, i.e., in the case of status hierarchies, the extent to which they appear to be supported by other members of the group. Obviously, status legitimacy refers to the degree to which the status of team members matches the value embodied in their personal characteristics or abilities as well as the degree to which they are supported by other members.

The level of status legitimacy determines the degree to which the current status level perceived by team members matches the value embodied in their personal characteristics or abilities, the degree to which the status distribution is fair and reasonable, and the degree to which the current status situation is supported by others (Kilduff et al., 2016). In cases of low status legitimacy, it is easy to trigger behaviors pertaining to power struggle (Ji et al., 2019). Power struggle forces team members to employ strategies such as coercion, threat and confrontation, which naturally weaken the internal cooperation of the team, thus shifting the stable team member relationship toward confrontation and conflict (Yu & Greer, 2022). Even if the status is stable, this situation also leads to mutual conflict and suspicion among team members (Greer & van kleef, 2010) and intensifies relationship conflict within the team. Furthermore, when status legitimacy is low, team members believe that their status does not match their ability or value characteristics, which creates a strong sense of unfairness; this sense of unfairness aggravates the opposition of team members who must compete due to their interests in obtaining the same status, and the possibility of mutual infringement and injury increases when members interact, thus leading to relationship conflict (Hays, 2017). In addition, low status legitimacy indicates that status hierarchy is inappropriate, incorrect and unfair and that the leader’s status is not based on his competence; team members thus deny the legitimacy of the allocation of status resources (Hays, 2013), and naturally avoid sharing information and voice for the completion of team tasks. Keeping silent regarding this problem is the most appropriate choice for them. The opposite approach leads to unfavorable situations such as retaliation by the leader. This situation naturally weakens the level of task conflict within the team.

When the level of status legitimacy improves, the situation changes. First, team members recognize the current status distribution and the value characteristics of other members, thereby reducing hostility and misunderstandings in the context of their interactions with others, easing conflicts, and enhancing the harmonious relationships with the team (Halevy et al., 2011). This situation thus reduces the level of relationship conflict within the team. Second, higher status legitimacy can elicit team members’ heartfelt recognition of status hierarchy. The recognition and affirmation of others’ status usually improves their relative value or contribution to the team, such as by causing them to invest more personal resources in work, participate in discussions concerning team tasks, and provide advice and suggestions for problem solving (Onu et al., 2015). This situation can also enhance the psychological safety of team members (Costa-Lopes et al., 2013). When their psychological safety is guaranteed, team members do not have to worry about the contradictions caused by status competition or about the unfairness of their own status. Instead, they can improve the internal interaction frequency and strengthen information exchange to promote team task completion. This situation is conducive to improving the team’s task conflict level. Based on this analysis, the following hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 3 (H3)

Status legitimacy positively moderates the relationship between status stability and relationship conflict.

Hypothesis 4 (H4)

Status legitimacy negatively moderates the relationship between status stability and task conflict;

Based on the preceding discussion, the following research model is proposed (Fig. 1):

Research design

Sample and data collection

In this study, sample data were collected using questionnaires. The samples were mainly drawn from 28 high-tech enterprises in China, which were largely focused on electronics, software development, manufacturing, energy, pharmaceutical and other industries. The questionnaire collection focused on the team level, and the teams included were involved in the development and output of new products or technologies; teams that did not involve creativity, such as the human resource management team, were excluded. The questionnaire distribution was strongly supported by the leaders of the abovementioned enterprises, and the on-site issuance and recovery method was adopted. To reduce the impact of common method bias, this study used a two-stage method to collect data, with an interval of 2 months. During the first stage, a total of 536 questionnaires were sent to 112 teams, which mainly measured status stability, relationship conflict, task conflict, status legitimacy and demographic information. After eliminating invalid questionnaires that featured regular completion or missing data, 446 valid questionnaires were obtained from 96 teams, for an effective recovery rate of 83.21% (the corresponding ratio at team level is 85.71%). During the second stage, 446 questionnaires were returned to the 96 teams that provided valid questionnaires during the first stage to measure team creativity. After eliminating invalid questionnaires based on the same criteria, 369 valid questionnaires were obtained from 83 teams, for an effective recovery rate of 82.74% (the corresponding ratio at team level is 86.46%). Statistical analysis of the valid questionnaires in the second stage revealed that team with more than 10 members accounted for 0.83% of the total, teams with 5–10 members accounted for 29.17%, and teams with 3–5 members accounted for 70.00%; teams with a tenure longer than 3 years accounted for 11.46% of the total, teams with a tenure of 1–3 years 62.50%, and teams with a tenure of less than 1 year accounted for 26.04%; and in terms of enterprise type, state-owned (holding) enterprises accounted for 21.36% of the total, private (holding) enterprises accounted for 61.16%, and foreign (holding) enterprises accounted for 17.48%.

Measures

Status stability

The status stability scale developed by Chang et al. (2019) for the Chinese context was used. The scale includes a total of 6 items, such as “the status level of team members virtually does not change” and “the ranking of status level among team members is stable”. The Cronbach’s alpha is 0.818.

Relationship conflict

The classic scale developed by Jehn (1995) was used to measure relationship conflict. This scale includes 4 items, such as “how much friction is there along members in your team” and “how much are personality conflicts in evidence in your team”. The Cronbach’s alpha is 0.857.

Task conflict

The classic scale developed by Jehn (1995) was used to measure task conflict. This scale includes 4 items, such as “How often do people in your team disagree about opinions regarding the work being done” and “How frequently are there conflicts about ideas in your team” The Cronbach’s alpha is 0.861.

Status legitimacy

This study developed a measurement scale for status legitimacy based on the work of Van Dijk and Van Engen (2013), Bettencourt et al. (2001), Kilduff et al. (2016) and other scholars. The scale includes four items: “the status arrangement on the team is reasonable”, “the status of team members matches their competency”, “the team members approve of the colleagues with higher positions than their own”, and “the allocation of members’ status in the team is appropriate”. The Cronbach’s alpha is 0.763.

Team creativity

The team creativity scale developed by Hanke (2006) was used. This scale consists of two subscales: novelty and usefulness. Usefulness consists of “the team’s design is worth doing”, “the team’s design is capable of being put into effect”, and “the team’s design is likely to produce the desired result”. Novelty consists of “the team’s design is excitingly different from what has been done previously”, “the team’s design represents a radical departure from traditional or previous practice”, and “the team’s design is one of a kind”. The Cronbach’s alpha is 0.802.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis

To ensure the discriminant validity of the main variables, AMOS 24.0 software was used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis on status stability, relationship conflict, task conflict, status legitimacy and team creativity. The confirmatory factor analysis results are shown in Table 1. The five-factor model has a good fit (χ2/df = 1.13, RMSEA = 0.04, NNFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.91, IFI = 0.92). The degree of fit exhibited by the four alternative models was poor and significantly different from that of the five-factor model. These results indicated that there was good discriminant validity among the variables. In addition, Harman’s single factor method was used to determine whether the sample faced a serious problem due to common method bias. The results indicated that the amount of variance explained by the first principal component explained variance was 19.14%, thus indicating that the common method bias problem was not prominent in this study.

Data aggregation

For a team-level study, it is necessary to aggregate the data for the relevant variables from the individual level to the team level. However, individual-level data aggregation must meet certain conditions. The conditions that must be satisfied are typically expressed in terms of Rwg, ICC (1) and ICC (2). Rwg refers to the consistency requirement within group, and the critical value commonly used in academia is 0.70. ICC (1) represents intragroup consistency, and ICC (2) represents intergroup consistency. The critical values of ICC (1) < 0.50 and ICC (2) > 0.50 were obtained. As shown in Table 2, the values of Rwg, ICC (1) and ICC (2), which were calculated by the statistical software R in this study, as well as all the results meet the critical conditions of Rwg > 0.70, ICC (1) < 0.50, and ICC (2) > 0.50 and satisfy the aggregation conditions. This outcome indicates that the data pertaining to the related variables differed sufficiently among teams and that the consistency was high at the team level, thus meeting the conditions for data aggregation.

Descriptive statistics

SPSS23.0 software was used to conduct descriptive statistical analysis on 8 variables including control variables, and their mean values, standard deviations and correlation coefficients are obtained (see Table 3). As shown in the Table 3, status stability is significantly correlated with team creativity (r = 0.253, P < 0.01), and status stability is significantly negatively correlated with relationship conflict (r=-0.413, P < 0.01). Similarly, status stability is significantly negatively correlated with task conflict (r=-0.332, P < 0.01). There is a significant positive correlation between task conflict and team creativity (r = 0.345, P < 0.01). There is a significant negative correlation between relationship conflict and team creativity (r= -0.427, P < 0.01). However, task conflict was not related to relationship conflict (r= -0.024, P < 0.05).

Hypothesis testing

The following tests are mainly based on the statistical software SPSS23.0 for linear regression analysis.

The mediating effect of relationship conflict

The method proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986) was used to test the mediating effect of knowledge sharing. First, the dependent variable team creativity was used to perform a linear regression on the independent variable status stability to obtain M1 (Table 4). According to M1, the total effect of status stability on team creativity in this study is significantly positive (β = 0.244, P < 0.01). Second, M4 was obtained by linear regression of the mediating variable relationship conflict on the independent variable status stability. According to M4, status stability has a significant negative effect on relationship conflict (β=-0.307, P < 0.01). Furthermore, team creativity was used to perform a simultaneous linear regression on status stability and relationship conflict to obtain M2. According to M2, relationship conflict has a significant effect on team creativity (β=-0.342, P < 0.01), and the effect of status stability on team creativity remains significant (β = 0.228, P < 0.01). Therefore, it can be concluded that relationship conflict has a partially mediating effect on the relationship between status stability and team creativity; thus, H1 is verified.

The mediating effect of task conflict

The method proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986) was also used to test the mediating effect of relationship conflict. First, M7 was obtained by linear regression of relationship conflict on status stability. According to M7, status stability has a significant negative effect on task conflict (β=-0.273, P < 0.01). Second, M3 was obtained by linear regression of team creativity on status stability and task conflict. According to M3, task conflict has a significant effect on team creativity (β=-0.264, P < 0.01), and status stability continues to have a significant effect on team creativity (β = 0.302, P < 0.01). Therefore, it can be concluded that task conflict partially mediates the relationship between status stability and team creativity, and H2 is thus verified.

The moderating effect of status legitimacy

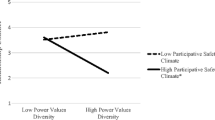

The moderating effect of status legitimacy in the relationship between status stability and relationship conflict was assessed as follows. First, M5 was obtained by adding status legitimacy to M4, following which M6 was obtained by adding an interaction item (status stability x status legitimacy) to M5. According to M6, the interaction item has a significant effect on team creativity (β = 0.184, P < 0.01), indicating that status legitimacy has a positive effect on the relationship between status stability and team creativity. That is, the higher the level of status legitimacy is, the stronger the negative effect of status stability on relationship conflict. In contrast, the lower the level of status legitimacy is, the weaker the negative effect of status stability on relationship conflict. Accordingly, H3 is verified (Fig. 2).

The moderating effect of status legitimacy on the relationship between status stability and relationship conflict was assessed as follows. First, M8 was obtained by adding status legitimacy to M7. Subsequently, the interaction item (status stability x status legitimacy) was added to M8 to obtain M9. According to M9, the interaction item has a significant effect on team creativity (β=-0.215, P < 0.01), indicating that status legitimacy has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between status stability and task conflict. That is, the higher the level of status legitimacy is, the weaker the negative effect of status stability on task conflict. In contrast, the lower that the level of status legitimacy is, the stronger the negative effect of status stability on task conflict. Accordingly, H4 is verified (Fig. 3).

Conclusions and implications

Discussion and conclusions

Based on empirical research, this study identifies team conflict (including relationship conflict and task conflict) as a mediator and status legitimacy as a moderator to explore the mechanism underlying the effect of status stability on team creativity. The findings are discussed as follows.

First, status stability has an impact on team creativity. As revealed by a review of the literature on team creativity, team composition (Somech & Drach-Zahavy, 2013), team cognition (Schippers et al., 2015), team process (Barczak et al., 2010), team leadership style (Hughes et al., 2018; He et al., 2020) and other influencing factors have been discussed. As a basic feature of team structure, the relationship between status stability and team creativity has not been fully studied, especially the process mechanism operative between these factors. On the one hand, on the basis of empirical research, this study confirmed that status stability has an impact on team creativity; that is, changes in status stability lead to changes in team creativity. On the other hand, it was found that team conflict has a mediating effect on the relationship between status stability and team creativity. Simultaneously, based on a process path analysis of different types of conflicts (task conflict and relationship conflict), it was found that status stability has a double-edged sword effect on team creativity. In this context, based on the relationship conflict path, status stability has a positive effect on team creativity, and based on the task conflict path, status stability has a negative effect on team creativity.

Second, status legitimacy effectively moderates the relationship between status stability and team creativity. Previous studies have shown that status legitimacy, as an important status characteristic, has mostly been included as a moderator in studies on the relationship between team characteristics and team performance (van Dijk & van Engen, 2013), team creativity (Aime et al., 2014), and intergroup relationships (Onu et al., 2015). However, most of these studies have focused on intergroup relationship and team outcome variables, and no research has focused on the combination of team conflict and status legitimacy. In fact, team process should be viewed as the result of interaction between team characteristics and organizational situational factors (Marks et al., 2001). On the basis of previous relevant research, this study used empirical research methods to verify the claim that under the moderating effect of status legitimacy, the negative effect of status stability on relationship conflict is enhanced, and the negative effect on task conflict is suppressed, thus ultimately ensuring a positive effect on team creativity.

Theoretical contributions

First, this study expands relevant studies in the field of status research. At present, the research on status stability remains in the exploratory stage, and the relevant research has mainly focused on its moderating effect (Bettencourt et al., 2001; Saguy & Dovidio, 2013; Hossain et al., 2020); few studies have discussed its main effect. Accordingly, this research attempts to inaugurate a special study on the impact of status stability on team creativity. Using different types of conflict (task conflict and relationship conflict) as mediators and status legitimacy as the moderator, this study systematically constructs a theoretical model of the effect of status stability on team creativity, which is helpful for exploring the mechanism underlying the effect of status stability on team creativity. By analyzing differences in the effectiveness of status stability, this study further enriches and deepens our understanding of status stability. Simultaneously, this study also expands the research horizon in the field of team creativity beyond previous research horizons, which have focused on factors affecting team creativity; in addition, it tries to study team creativity from the perspective of status stability (one of the characteristics of team structure).

Second, this study transcends the previous perspective of status stability research. On the one hand, this study discusses status stability from a holistic perspective. In relevant studies of status stability, most scholars have divided team members into two categories: high-status members and low-status members. Such researchers have claimed that status stability gas a differentiated effect on the behavior of members at different levels (Ellemers et al., 2010; Halabi et al., 2014; Park et al., 2017). These studies have treated team members differently and ignored any overall discussion of the team. On the one hand, this study also discusses the effectiveness of status stability from different perspectives and reconciles previous differences regarding the effect of status stability on team effectiveness. Previous studies have proposed two contradictory views of status stability: functionalism (Anderson & Willer, 2014) and conflict theory (Anderson & Brown, 2010). However, such contradictory views have often been studied separately. Few studies have discussed these two views of status stability simultaneously under the same theoretical framework, which is obviously one-sided.

Practical contributions

First, a moderate level of status stability can stimulate team creativity. In the practice of organizational management, managers should realize that status stability has a “double-edged sword” effect; that is, different levels of status stability allocation may have different effects on team creativity. Unreasonable status stability allocation may not only aggravate the relationship conflict caused by status competition within the team but also cause the team to become a stagnant pool due to the unchanged status quo, thus limiting task conflict and decreasing innovation vitality. Accordingly, managers can improve team status stability by formulating appropriate management systems to establish a moderate and stable working environment for team members to stimulate team creativity. Specifically, managers can implement appropriate promotion and elimination systems and identify appropriate time nodes to organize regular evaluation, thereby sending a signal to members regarding the possibility of changing the current status and the potential threats contained in this possibility, promoting the work vitality of team members, reasonably matching the existing resources of the team, and thus creating the conditions necessary for the improvement of team creativity.

Second, attention should be given to the characteristics of status legitimacy. This study confirmed that status legitimacy can effectively moderate the final effect of status stability on team creativity. When status legitimacy is high, it can strengthen the constructive effect of status stability on relationship conflict, and alleviate the destructive effect of status stability on task conflict. Therefore, managers can achieve the goal of managing task conflicts and relationship conflicts by adjusting the characteristics of status legitimacy. Specifically, managers can link status with ability and contribution in the process of designing the status hierarchy and can improve the reasonability and legitimacy of members’ perceptions of status allocation by improving the degree of match between the value embodied by members’ personal abilities and their status or by improving the fairness of status allocation to effectively control the relationship conflict within the team. It is also possible to establish a standard for status allocation and to grant low-status members the right to participate in discussions on various major issues and express their opinions fully with the aim of increasing the team’s psychological safety atmosphere and thus stimulating task conflict within the team.

Limitations and directions for future research

Although this study produced several significant results, it also faces a number of shortcomings. First, this study considered only the moderating effect of the system design of status legitimacy. However, the system design of organizations should be diversified. To effectively improve the positive effect of status stability on team creativity, other aspects of system design should be considered, for example, justice of distribution, sense of legal status, team motivation, and status culture. Second, this study failed to distinguish among the levels of status stability of different types of enterprises. In reality, the levels of status stability of different enterprises can vary (e.g., state-owned enterprises are higher than private enterprises), and the effect of status stability on team creativity may also be different across enterprises. In the future research, a comparative analysis based on the sufficient sample size can be conducted to determine how the effects of different enterprises’ status stability on team creativity differ. Third, based on the fact that all variables in this study were measured by employees’ self-assessment, although reverse scoring and other methods were used to control for mechanistic answering on the part of respondents, it may still have been possible for homologous errors to affect the research results. In future research, we can consider collecting data in batches, to expand the diversity of data sources, or measuring some variables in ways other than self-assessment.

Conclusion

Our research confirmed that status stability has a double-edged sword effect; that is, it has both constructive and destructive effects. Its constructive effects are reflected in its positive effect on team creativity by reducing relationship conflict, while its destructive effects pertain to its negative effect on team creativity by limiting task conflict. However, under the moderating effect of status legitimacy, the destructive effect of status stability is mitigated, and the constructive effect is enhanced, thus effectively ensuring the positive effect of status stability on team creativity. By highlighting the mechanism underlying the effect of status stability on team creativity, this research can provide a useful reference for team and even enterprise hierarchy design.

References

Aggarwal, I., & Woolley, A. W. (2019). Team creativity, cognition, and cognitive style diversity. Management Science, 65, 1586–1599.

Aime, F., Humphrey, S., DeRue, D. S., & Paul, J. B. (2014). The riddle of heterarchy: power transitions in cross-functional teams. Academy of Management Journal, 57(2), 327–352.

Anderson, C., & Brown, C. E. (2010). The functions and dysfunctions of hierarchy. Research in organizational behavior, 30, 55–89.

Anderson, C., & Kennedy, J. A. (2012). Micropolitics: A new model of status hierarchies in teams. In Looking back, moving forward: A review of group and team-based research, 15, 49–80.

Anderson, C., & Willer, R. (2014). Do status hierarchies benefit groups? A bounded functionalist account of status. The psychology of social status. New York, NY: Springer.

Anicich, E. M., Fast, N. J., Halevy, N., & Galinsky, A. D. (2016). When the bases of social hierarchy collide: power without status drives interpersonal conflict. Organization Science, 27(1), 123–140.

Barczak, G., Lassk, F., & Mulki, J. (2010). Antecedents of team creativity: an examination of team emotional intelligence, team trust and collaborative culture. Creativity and innovation management, 19(4), 332–345.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of personality and social psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Bettencourt, B., Charlton, K., Dorr, N., & Hume, D. L. (2001). Status differences and in-group bias: a meta-analytic examination of the effects of status stability, status legitimacy, and group permeability. Psychological bulletin, 127(4), 520–542.

Bettencourt, B. A., & Bartholow, B. D. (1998). The importance of status legitimacy for intergroup attitudes among numerical minorities. Journal of Social Issues, 54(4), 759–775.

Bidwell, M. J. (2013). What happened to long-term employment? The role of worker power and environmental turbulence in explaining declines in worker tenure. Organization Science, 24(4), 1061–1082.

Bitektine, A. (2011). Toward a theory of social judgments of organizations: the case of legitimacy, reputation, and status. Academy of management review, 36(1), 151–179.

Brandt, M. J., Kuppens, T., Spears, R., Andrighetto, L., Autin, F., Babincak, P., & Zimmerman, J. L. (2020). Subjective status and perceived legitimacy across countries. European Journal of Social Psychology, 50(5), 921–942.

Bunderson, J. S., & Boumgarden, P. (2010). Structure and learning in self-managed teams: why “bureaucratic” teams can be better learners. Organization Science, 21(3), 609–624.

Chang, T., & Pei, F. X. (2022). The inverted U-shaped relationship between team status disparity and team creatity: Moderating effect task characteristics. Science & Technology Progress and Policy, 39, 133–141.

Chang, T., Wu, J. M., & Liu, Z. Q. (2019). Status stability and team creativity:The effect of related task Characteristics,Science of Science and Management of S.& T, 40, 119–134.

Costa-Lopes, R., Dovidio, J. F., Pereira, C. R., & Jost, J. T. (2013). Social psychological perspectives on the legitimation of social inequality: past, present and future. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(4), 229–237.

Ellemers, N., Knippenberg, A. V., Vries, N. D., & Wilke, H. (2010). Social identification and permeability of group boundaries. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18(6), 497–513.

Farh, J. L., Lee, C., & Farh, C. I. (2010). Task conflict and team creativity: a question of how much and when. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(6), 1173–1180.

Gray, B., & Ariss, S. S. (1985). Politics and strategic change across organizational life cycles. Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 707–723.

Greer, L. L., de Jong, B. A., Schouten, M. E., & Dannals, J. E. (2018). Why and when hierarchy impacts team effectiveness: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Applied Psychology, 2018, 103(6), 591–613.

Greer, L. L., & van Kleef, G. A. (2010). Equality versus differentiation: the effects of power dispersion on group interaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(6), 1032–1044.

Halabi, S., Dovidio, J. F., & Nadler, A. (2014). Seeking help from the low status group: Effects of status stability, type of help and social categorization. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 53, 139–144.

Halevy, N., Chou, E. Y., & Galinsky, A. D. (2011). A functional model of hierarchy: why, how, and when vertical differentiation enhances group performance. Organizational Psychology Review, 1(1), 32–52.

Hanke, R. C. (2006). Team creativity: a process model. The Pennsylvania State University, Pennsylvania.

Hays, N. A. (2013). Fear and loving in social hierarchy: sex differences in preferences for power versus status. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(6), 1130–1136.

Hays, N. A., & Bendersky, C. (2015). Not all inequality is created equal: Effects of status versus power hierarchies on competition for upward mobility. Journal of personality and social psychology, 108(6), 867–882.

Hays, N. A., & Blader, S. L. (2017). To give or not to give? Interactive effects of status and legitimacy on generosity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(1), 17–38.

He, W., Hao, P., Huang, X., Long, L. R., Hiller, N. J., & Li, S. L. (2020). Different roles of shared and vertical leadership in promoting team creativity: cultivating and synthesizing team members’ individual creativity. Personnel Psychology, 73(1), 199–225.

Hossain, M. Y., Liu, Z., & Kumar, N. (2020). How does self-performance expectation foster breakthrough creativity in the employee’s cognitive level? An application of self-fulfilling prophecy. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 9(5), 116–128.

Hu, Q., & Xie, X. (2015). Group Members’ Status and Knowledge sharing behavior: a motivational perspective. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 47(4), 545–554.

Hughes, D. J., Lee, A., Tian, A. W., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2018). Leadership, creativity, and innovation: a critical review and practical recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(5), 549–569.

Jehn, K. A. (1995). A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Administrative science quarterly, 40, 256–282.

Ji, H., Xie, X. Y., Xiao, Y. P., Gan, X. L., & Feng, W. (2019). Does power hierarchy benefit or hurt team performance? The roles of hierarchical consistency and power struggle. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 51(3), 366–382.

Jung, E. J., & Lee, S. (2015). The combined effects of relationship conflict and the relational self on creativity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 130, 44–57.

Kemper, T. D. (2016). Status, power and ritual interaction: A relational reading of Durkheim, Goffman and Collins. Routledge.

Kilduff, G. J., Willer, R., & Anderson, C. (2016). Hierarchy and its discontents: Status disagreement leads to withdrawal of contribution and lower group performance. Organization Science, 27(2), 373–390.

Lau, R. S., & Cobb, A. T. (2010). Understanding the connections between relationship conflict and performance: the intervening roles of trust and exchange. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(6), 898–917.

Lee, E. K., Avgar, A. C., Park, W. W., & Choi, D. (2018). The dual effects of task conflict on team creativity: focusing on the role of team-focused transformational leadership. International Journal of Conflict Management, 30, 132–154.

Lee, H. W., Choi, J. N., & Kim, S. (2018). Does gender diversity help teams constructively manage status conflict? An evolutionary perspective of status conflict, team psychological safety, and team creativity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 144, 187–199.

Li, W., Yang, Y., Wu, J., & Kou, Y. (2020). Testing the status-legitimacy hypothesis in China: objective and subjective socioeconomic status divergently predict system justification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46, 1044–1058.

Liu, Z., Wei, L., Zhou, K., & Liao, S. (2019). Double sides of status conflict and team innovation. Nankai Business Review, 4, 176–186.

Luo, S., Wang, J., Xiao, Y., & Tong, D. Y. K. (2020). Two-path model of information sharing in new product development activities. Information Development, 36, 312–326.

Marks, M. A., Mathieu, J. E., & Zaccaro, S. J. (2001). A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes. Academy of management review, 26(3), 356–376.

Onu, D., Smith, J. R., & Kessler, T. (2015). Intergroup emulation: an improvement strategy for lower status groups. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 18(2), 210–224.

O’Toole, J., Galbraith, J., & Lawler, I. I. I. (2002). When two (or more) heads are better than one: the promise and pitfalls of shared leadership. California management review, 44(4), 65–83.

Park, S. H., Kim, H. J., & Park, Y. O. (2017). Cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to ingroup’s devalued social status: a field study at a public university. Current Psychology, 36, 22–38.

Pearce, J. L. (2011). Status in management and organizations. Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal, 25, 08125.

Pillay, N., Park, G., Kim, Y. K., & Lee, S. (2020). Thanks for your ideas: Gratitude and team creativity. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 156, 69–81.

Saguy, T., & Dovidio, J. F. (2013). Insecure status relations shape preferences for the content of intergroup contact. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(8), 1030–1042.

Schippers, M. C., West, M. A., & Dawson, J. F. (2015). Team reflexivity and innovation: the moderating role of team context. Journal of Management, 41(3), 769–788.

Shepherd, L., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. (2013). When does anticipating group-based shame lead to lower ingroup favoritism? The role of status and status stability. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(3), 334–343.

Simons, T. L., & Peterson, R. S. (2000). Task conflict and relationship conflict in top management teams: the pivotal role of intragroup trust. Journal of applied psychology, 85(1), 102–111.

Shin, N. J., Ziegert, J. C., & Muethel, M. (2022). The detrimental effects of ethical incongruence in teams: an interactionist perspective of ethical fit on relationship conflict and information sharing. Journal of Business Ethics, 179(1), 259–272.

Sligte, D. J., Dreu, C., & Nijstad, B. A. (2011). Power, stability of power, and creativity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(5), 891–897.

Somech, A., & Drach-Zahavy, A. (2013). Translating team creativity to innovation implementation: the role of team composition and climate for innovation. Journal of management, 39(3), 684–708.

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Chicago, IL: Nelson Hall.

Tarakci, M., Greer, L. L., & Groenen, P. J. (2016). When does power disparity help or hurt group performance? Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(3), 415–429.

van Dijk, H., & van Engen, M. L. (2013). A status perspective on the consequences of work group diversity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(2), 223–241.

Van Bunderen, L., Greer, L. L., & Van Knippenberg, D. (2018). When interteam conflict spirals into intrateam power struggles: the pivotal role of team power structures. Academy of Management Journal, 61(3), 1100–1130.

Yu, S., & Greer, L. L. (2022). The role of Resources in the success or failure of Diverse Teams: Resource Scarcity activates negative performance-detracting Resource Dynamics in Social Category Diverse Teams. Organization Science, 1, 1560.

Zhu, Y., Xie, J., Jin, Y., & Shi, J. (2019). Power disparity and team conflict: the roles of procedural justice and legitimacy. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 51, 829–840.

Funding

Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (Project No. LQ22G020007); Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project of the Ministry of Education (22YJC630168).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, S., Wang, J., Xie, Z. et al. Does status stability benefit or hurt team creativity? the roles of status legitimacy and team conflict. Curr Psychol 43, 942–953 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04332-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04332-7