Abstract

Previous research indicates narcissism can aid stress management. Nonetheless, its common perception and dissemination as socially aversive may hamper its acknowledgment and use as an asset in the context of stress. This experimental study investigated the effects of receiving positive or negative information (i.e., prompts) about narcissism in the context of stress on attitudes towards this trait’s association with stress. It also assessed individuals’ experiences of narcissism’s stress-coping properties when one believes themselves to be a high narcissism scorer, via an online survey. Hundred and five adults (\({M}_{age}\) = 32.0; 22–64 years) completed measures of state-stress, music preferences, and narcissism. They were then randomly assigned to either the positive or negative prompt groups, being shown information highlighting the positive or negative impact of narcissism on stress management, respectively. Participants were then informed they scored above average on narcissism, despite their actual questionnaire scores, and undertook a stress-inducing procedure. Self-reported stress, implicit and explicit attitudes were measured pre- and post-prompt presentation. Results showed that, while prompts did not influence attitudes nor stress outcomes, individuals displayed neutral implicit attitudes towards narcissism’s association with stress across measurement timepoints. These findings suggest that people’s attitudes towards narcissism in the context of stress have not been deteriorated by this trait’s predominant negative depiction outside this context. Therefore, the dissemination and establishment of narcissism as an asset for stress-coping may be received by the general population with less resistance than anticipated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Stress is a state of imbalance in which external or internal demands are perceived to exceed one’s available coping resources (Colman, 2015; Fink, 2010). It is inherent to the human experience and, depending on how one responds to it, it can be substantially detrimental to well-being and everyday functioning (Fink, 2010). Several personality traits have been found to foster adaptive stress responses and/or diminish the manifestation of maladaptive ones (Darshani, 2014; Kaur, 2015; Kilby et al., 2018; Soliemanifar et al., 2018). Though many of these traits are predominantly desirable across contexts (e.g., mental toughness), other less unequivocally advantageous traits may also protect against the negative effects of everyday stress (Gomes Arrulo-Clarke et al., n.d.)). This is the case with subclinical narcissism which, despite evidence highlighting its association with stress-coping (Gomes Arrulo et al., 2021, 2022; Papageorgiou et al., 2019c), remains predominantly regarded as aversive (e.g., Hartung et al., 2021; Ścigała et al., 2021). Thus, compared to desirable traits, the acknowledgement of narcissism as beneficial for stress-coping may be harder to foster.

Subclinical narcissism is a personality trait that is part of the Dark Triad (DT), a personality cluster with a widespread malevolent connotation (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Narcissism is characterized by a sense of superiority, entitlement, and inflated self-image, and is often associated with socially undesirable behaviors (e.g., aggression, use of antisocial tactics) (Muris et al., 2017). Though widely perceived as aversive, research has reported links between narcissism and successful mental health outcomes (e.g., improved psychological health, adaptive tendencies against psychopathology) (Papageorgiou et al., 2019b; Sedikides et al., 2004). As previously mentioned, the associations between narcissism and stress have been particularly noteworthy, as evidence suggests narcissism offers a unique contribution to stress-coping, compared to other “dark” traits (e.g., Machiavellianism) (Gomes Arrulo et al., 2021; Papageorgiou et al., 2019a). In fact, growing evidence highlighting the benefits of narcissism in this context has challenged its inclusion in the DT cluster (Papageorgiou et al., 2019c), setting it apart from other negatively perceived traits.

Narcissism has been linked to favorable physiological (e.g., lower skin conductance response and cardiac deceleration in anticipation of an aversive stimulus) (Kelsey et al., 2001) and psychological (e.g., perceived stress) stress responses (Papageorgiou et al., 2019c; Richardson & Boag, 2016). More recently, narcissism’s stress-coping properties have been found to manifest themselves across different environments (i.e., within and beyond laboratory settings) and in the presence of different types of stressors (e.g., face-to-face and remote stress induction) (Gomes Arrulo et al., 2021, 2022). The recurrence of these advantageous effects reinforces the uniqueness of narcissism as a “dark” trait with valuable adaptive features in this context. Yet, the term “narcissism” remains widely stigmatized in the media, being broadly, and sometimes misguidedly, used to portray those who display self-promoting and individualistic behaviors in a negative light (Freestone et al., 2020).

Media sources can influence individuals’ perception of the topics it portrays, with the positive or negative framing of such topics often shaping one’s attitudes towards them (Oredein et al., 2020). This can occur via observational learning (i.e., individuals observing a model and using the information gathered to guide own actions), according to social learning theory (Bandura & McClelland, 1977). Mass media can occupy a central role in everyday learning as a powerful symbolic (i.e., real/fictional characters behaving in films, books, media) or verbal instructional (i.e., descriptions/explanations regarding a behavior) model (Bandura & McClelland, 1977; O’Rorke, 2006). This role becomes exacerbated when considering our current unprecedented accessibility and susceptibility to mass media (Fletcher & Park, 2017). Given this and the pervasive dissemination of the costs related to narcissistic behaviors in the media (Freestone et al., 2020), one may interiorize narcissism as fundamentally unfavorable via exposure to mass media. Moreover, literature suggests the excessive emphasis of narcissism as representing morally perverse everyday behaviors can negate its complexity in the public eye (Freestone et al., 2020). Therefore, people may also become hesitant or unwilling to recognize narcissism’s contextual advantages, and wrongly extend its widespread aversiveness to the context of stress. Additionally, narcissists may often manifest interpersonal difficulties, debilitated well-being, and negative health outcomes, such as suicidal behavior (Freestone et al., 2020). Notably, individuals at risk of suicide have been found to seek information regarding suicidality and self-harm in media sources (Gimbrone et al., 2021). Therefore, although affective temperaments may help determine actual lifetime suicide attempts (Baldessarini et al., 2017), the excessively negative representation of narcissism in the media may also perpetuate the manifestation of suicidal tendencies in narcissists.

By shaping individuals’ attitudes and expectations, observational learning may also modulate how the stress-coping properties of narcissism are manifested and experienced. In fact, observational learning has been found to facilitate the emergence of placebo and nocebo effects (Bajcar & Bąbel, 2018). Thus, the manifestation of narcissism’s stress-coping properties may vary in function of learned attitudes towards and expectations regarding this trait. Though several studies have reported the effects of narcissism on stress (e.g., Coleman et al., 2019; Gomes Arrulo et al., 2021, 2022; Papageorgiou et al., 2019c), no research to date has yet investigated whether learned information about such effects can alter their manifestation.

Considering this, while empirical evidence has provided valuable insight into the role of narcissism for stress-coping, its benefits may be received with resistance from the general population due to its widespread aversiveness. Such resistance may translate into (1) a reluctance to recognize narcissism as contextually beneficial or avail of its stress-coping benefits, and (2) a weakened manifestation of such benefits. Thus, to establish narcissism as an asset to stress management, we must first examine the extent of this resistance and whether it can be overcome by exposure to information regarding its advantageous contribution to stress-coping.

Present study

This study will investigate the effects of receiving positive or negative information (i.e., prompts, as small-scale verbal instructional models resembling mass media) regarding narcissism in the context of stress on (1) attitudes towards this trait’s association with stress and (2) actual experiences of its stress-coping properties if one believes themselves to be a high narcissism scorer, in healthy adults. Referring to these main study aims, it was hypothesized that those presented with a positive prompt (i.e., ‘positive prompt’ group) would display (1) more positive attitudes and (2) lower stress levels post-prompt, compared to those presented with a negative prompt (i.e., ‘negative prompt’ group).

It should be noted that narcissism has been found to predict beneficial stress responses both directly and indirectly (i.e., moderated by classical music preferences and habitual music uses) in experimental studies using stress-inducing paradigms (Gomes Arrulo et al., 2021, 2022). However, these advantageous effects have not been consistently reported in Gomes Arrulo et al. (2021) and in Gomes Arrulo et al. (2022). Therefore, to consolidate the role of narcissism in this context, the effects of narcissism, both direct and as moderated by classical music preferences and habitual music uses, on stress levels reported before and after successful stress induction will also be examined as additional analyses, as per Gomes Arrulo et al. (2021) and Gomes Arrulo et al. (2022). A modified version of the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) (Kirschbaum et al., 1993), a reliable stress induction procedure (Allen et al., 2017), was used to induce stress remotely, as per Gomes Arrulo et al. (2022), as the present study was conducted via an online survey.

Methods

Pilot study

A pilot study (N = 10; M = 27.9 years, SD = 12.2; 70% females) was conducted to assess the feasibility of the procedure (see Pilot Study Analysis in Online Resource 1).

The outcomes from an a priori power analysis using G*Power 3 (Faul et al., 2007) indicated that a sample of 99 participants would be required to achieve a power of 0.80, α = 0.05. The values for the slopes and standard deviations for the predictor and outcome variables were determined using data derived from a previous study concerning the effect of narcissism on stress (Gomes Arrulo et al., 2022).

Participants

Participants self-selected to take part in this study via an advertisement posted on Amazon Mechanical Turk (Mturk). Participants were required to be 18 years old or above. Individuals who were taking medication for and/or had been diagnosed with any psychiatric/psychological disorder(s), had experienced a traumatic event in the month preceding survey completion, and/or were pregnant were excluded from the study.

Initial survey entries were removed if (1) they consisted of a duplicated (n = 405) and/or incomplete (n = 201) response, (2) they were flagged as ‘spam’ by the survey software (n = 10), (3) participants admitted to not have followed the instructions accurately (n = 93), (4) participants responded “yes” to at least one of the exclusion criteria (n = 77), and/or (5) participants failed two or more attention checks in the survey (n = 1). Six participants were added to the estimated target sample size (N = 99) to account for other potential issues (e.g., missing data). However, as no further removals were necessary, the final sample consisted of 105 adults (\({M}_{age}\) = 32.0; SD = 8.3, range = 22–64 years; 59.0% females, 41.0% males). Regarding ethnic background, 76.2% identified as White, 16.2% as Black, African, Caribbean, or Black British, 5.7% as Asian or Asian British, 1.0% selected ‘Mixed or Multiple Ethnic Groups’, and 1.0% selected ‘Other’; 97.1% were native English speakers. All participants received a £2.25 payment. This study was approved by the Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Ethics Committee (EPS 21_112).

Materials

Stress manipulation

A modified TSST (Kirschbaum et al., 1993) developed for a previous study was used to induce mild to moderate acute stress remotely (see Stress Manipulation in Online Resource 1 for details on the original procedure). Participants were initially asked to imagine they had applied for their ideal job and given three minutes to prepare a convincing speech explaining why they were the most suitable candidate for the position. They were told they would need to record this speech later on via webcam for their suitability for the role to be subsequently assessed. Participants were then instructed to count backward from 2023 in decrements of 17 and to input the results of each mental calculation in writing. They were asked to restart from 2023 after every wrong answer. The mental arithmetic task lasted five minutes. In reality, participants did not have to record nor deliver their speech, though they were not made aware of this until the end of the experiment.

Measures

The Short Dark Triad questionnaire (SD3) – ‘Narcissism’ subscale (Jones & Paulhus, 2014), the Short Test of Music Preferences Revised (STOMP-R) (Rentfrow & Gosling, 2003), and the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS21) – ‘Stress’ subscale (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) were used to measure narcissism, classical music preferences, and state-stress, respectively (see Measures in Online Resource 1). A single question asking participants to indicate the purposes for which they usually listened to music (i.e., emotion regulation, entertainment, relaxation, stimulation, or ‘other’) was used to measure habitual music uses. Only ‘emotion regulation’ and ‘relaxation’ were of interest, as per Gomes Arrulo et al. (2021)’s findings. Explicit attitudes towards narcissism in the context of stress were measured using a 3-item questionnaire asking participants to indicate to what extent they associated narcissism with stress management, stress-coping ability, and stress regulation, separately, via a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much). The higher the sum of scores on each item, the more positive one’s explicit attitudes towards narcissism in the context of stress. Aggregated explicit attitudes scores ranged from 3 to 15. Stress levels were measured using a 10-point Likert scale (1 = not stressed at all, 10 = extremely stressed).

The Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald et al., 1998) was used to measure implicit attitudes towards narcissism in the context of stress via iatgen, a tool that builds and analyses IATs within Qualtrics surveys (Carpenter et al., 2019). IATs assess implicit links between target concepts and evaluative categories through a set of seven stimuli blocks, in which participants are asked to sort words or images representing a target or category by pressing the “e” or “i” keys on their keyboard, according to whether the stimulus displayed belongs to the concept/category presented on the left or the right of the screen, respectively (Carpenter et al., 2019).

In this study, ‘narcissistic personality’/ ‘non-narcissistic personality’ were used as target concepts and ‘beneficial to stress-coping’/ ‘not beneficial to stress-coping’ as evaluative categories (see Words Presented in IAT in Online Resource 1). Following the traditional IAT procedure, the blocks used were as follows: blocks 1 and 2 (20 trials each), which were practice blocks presenting target concepts only and evaluative categories only, respectively; a combined block made up of blocks 3 (20 practice trials) and 4 (40 critical trials), presenting paired target concepts and evaluative categories; block 5 (40 trials), a practice block presenting evaluative categories displayed on the opposite side of the screen in which they were displayed in block 2; and a second combined block consisting of blocks 6 (20 practice trials) and 7 (40 critical trials), presenting paired concepts and categories in their reversed position compared to the first combined block (see Fig. 1) (Carpenter et al., 2019; Greenwald et al., 1998). Following Greenwald et al.’s (1998) methodology, a D-score (i.e., overall standardized difference score) was computed for each participant using the data recorded in the combined blocks (Carpenter et al., 2019; Greenwald et al., 1998). Positive D-scores were interpreted as positive implicit attitudes, as these indicated participants responded faster when ‘narcissistic personality’ was paired with ‘beneficial to stress-coping’. Negative D-scores were interpreted as negative implicit attitudes, as these indicated participants responded faster when ‘narcissistic personality’ was paired with ‘not beneficial to stress-coping’. D-scores of 0 were interpreted as neutral attitudes, as this indicated there were no differences in response speeds between the two combined blocks.

Design

This study was a double-blind randomized controlled trial using a mixed design. The independent variables were prompt group and time. The prompt group, a between-participants variable, had 2 levels: ‘positive’ and ‘negative’. Time, a within-participants variable, had 2 levels: ‘pre-prompt’ and ‘post-prompt’. The dependent variables were explicit attitudes, implicit attitudes, and self-reported stress levels (ranging from 0 to 10), recorded at pre- and post-prompt. State-stress was included as a covariate, where appropriate, to control for individual differences in the emotional state of stress. ‘Narcissism scores’, a between-participants variable ranging from 1 to 5, was added to assess the relationship between narcissism and stress, as additional analyses. Preference for classical music, ranging from 1 to 7, and music uses, both between-participants variables, were added as potential moderators in the relationship between narcissism and stress.

Apparatus and procedure

Potential participants were initially informed the study investigated the relationship between personality and cognitive performance. Participants were not made aware of the real study aims nor its stress-inducing component. After signing up for the study, participants were directed to an online Qualtrics survey to be completed using a laptop/computer and randomly assigned to the positive or negative prompt group via a Qualtrics’ randomizer tool. Once written informed consent was given, participants’ eligibility was confirmed using a pre-screening questionnaire. Ineligible individuals were directed to the end of the survey and no compensation was awarded. Those deemed eligible completed a demographics form and measures of music preferences, music uses, and state-stress. Pre-prompt stress levels, as well as implicit and explicit attitudes towards narcissism in the context of stress were then measured. Following this, narcissism scores were recorded. The positive prompt group was then shown information linking narcissism to positive stress outcomes, while the negative prompt group was shown information linking narcissism to negative stress outcomes (see Prompts in Online Resource 1). All participants were then told they had scored above average on the narcissism questionnaire, irrespective of their actual scores, and undertook the stress-inducing procedure. Immediately after this, post-prompt stress levels, as well as implicit and explicit attitudes towards narcissism in the context of stress were measured. Participants were then fully debriefed and compensated for their time. The survey included attention and data quality checks throughout to verify participants responded attentively and followed instructions carefully (see Attention and Data Quality Checks in Online Resource 1). The overall duration of the experiment was approximately 40–50 min. The experimental timeline is displayed in Fig. 2.

Statistical analyses

Paired samples t-tests were conducted to examine differences in explicit and implicit attitudes measured pre- and post-prompt. Independent t-tests were used to assess differences in explicit and implicit attitudes between groups. A two-way mixed ANCOVA, with state-stress included as a covariate, was used to examine the effectiveness of the stress manipulation and differences in stress levels between groups. Simple linear regressions were used as additional analysis to examine the direct relationship between narcissism and stress. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses, with state-stress added as a covariate, were used to assess the moderating effect of classical music preferences and habitual music uses on the relationship between narcissism and stress. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac Version 27 and the iatgen R package (Carpenter et al., 2021; R Core Team, 2018).

Results

Descriptive statistics for all variables of interest are displayed in Table 1.

Implicit & explicit attitudes

Two independent t-tests and two paired samples t-tests showed there were no significant differences in explicit and implicit attitudes between prompt groups nor in pre- to post-prompt explicit and implicit attitudes within each prompt group, respectively. Additionally, both the positive and the negative prompt group displayed neutral implicit attitudes (i.e., not significantly different from zero) towards narcissism in the context of stress both pre- and post-prompt (see Table 2; see IAT Density Plots in Online Resource 1).

Stress outcomes

A two-way 2 × 2 mixed ANCOVA was conducted to examine the effects of prompt group (positive, negative) and time (pre-prompt, post-prompt) on stress. State-stress was included as a covariate. The ANCOVA, with a Huynh–Feldt correction, showed that there was a main effect of time, F (1, 102) = 5.80, p = 0.018, \({\upeta }_{p}^{2}\)= 0.05, with participants reporting higher stress levels after stress induction (i.e., post-prompt) than at baseline (i.e., pre-prompt). This indicates that the stress manipulation was successful. There was also a main effect of prompt group, F (1, 102) = 4.03, p = 0.047, \({\upeta }_{p}^{2}\)= 0.04, with the negative prompt group being, overall, more stressed than the positive prompt group (see Table 1). The time by prompt group interaction was not significant. Changes in mean stress levels over time per prompt group are displayed in Fig. 3.

Narcissism & stress

Reliability coefficients for the narcissism trait measure are displayed in Table 3.

Two simple linear regressions were conducted to test if narcissism scores significantly predicted stress levels over time. The results of the regressions indicated narcissism scores did not explain a significant amount of the variance in pre-prompt stress levels, F (1, 103) = 0.46, p = 0.501, or post-prompt stress levels, F (1, 103) = 0.08, p = 0.782. The regression coefficients (see Table 4) indicated narcissism scores predicted, on average, an increase in pre-prompt stress levels by 0.46 points (out of 10) and a decrease in post-prompt stress levels by 0.18 points (out of 10).

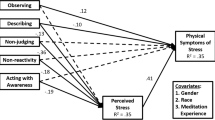

A series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses were also performed to assess the moderating effect of classical music preferences and music uses on the relationship between narcissism and stress, with state-stress added as a covariate. Narcissism scores and both moderator variables were centered to reduce multicollinearity issues (Aiken et al., 1991). Stress levels reported pre- and post-prompt were added as outcome variables, narcissism scores as a predictor, and classical music preferences and music uses as moderators into separate regression models.

Two hierarchical multiple regression analyses assessed the moderating effect of classical music preferences on the relationship between narcissism and both pre-prompt and post-prompt stress levels (see Table 5). Classical music preference did not moderate the relationship between narcissism and stress over time.

Two additional hierarchical multiple regression analyses assessed the moderating effect of music uses on the relationship between narcissism and both pre-prompt and post-prompt stress levels, with state-stress added as a covariate (see Table 6). It should be noted the category ‘emotion regulation’ could not be compared to ‘neither relaxation nor emotion regulation’ due to the extremely low sample size in this category (see Table 1). Music uses did not moderate the relationship between narcissism and stress over time.

Discussion

The main study findings revealed that receiving a positive or negative prompt did not influence participants’ attitudes towards narcissism nor stress outcomes. However, individuals displayed neutral implicit attitudes towards narcissism in association with stress across measurement timepoints. These findings suggest that the predominant negative depiction of narcissism outside the context of stress has not had a negative impact on attitudes within it. Thus, while previous findings have identified advantageous manifestations of narcissism in the stress domain (e.g., Gomes Arrulo et al., 2021, 2022; Papageorgiou et al., 2019a, 2019c), our study shows that the dissemination of such findings and the establishment of narcissism as an asset for stress-coping may be received with less resistance than anticipated.

Contradicting our hypothesis, being presented with positive evidence regarding the association between narcissism and stress did not influence implicit nor explicit attitudes. Participants did, however, display neutral implicit attitudes towards narcissism in the context of stress throughout the experiment. Additionally, the mean aggregated explicit attitudes scores, though not associated with significant effects, indicated that neither group held extremely positive nor extremely negative explicit attitudes across measurement timepoints. This is consistent with previous research reporting that narcissism tends to be perceived more favorably than other “dark” traits (e.g., Machiavellianism, psychopathy), though narcissistic individuals are still not usually perceived positively, overall (Rauthmann & Kolar, 2012, 2013). Literature suggests that, although narcissism is commonly included in “dark” personality clusters and categorized as a socially aversive trait, people may perceive some narcissistic tendencies (e.g., seeking status and prestige) as appealing, rather than repulsive (Rauthmann & Kolar, 2013). This mix of desirable and undesirable connotations might explain the neutral attitudes observed in this study. If these did rely on a balance between positive and negative pre-existing perceptions, then the positive prompt presented may have just not been impactful enough to disrupt such balance, explaining the reported findings.

Receiving a positive prompt about narcissism in the context of stress did not improve stress outcomes either. This is contrary to our predictions and previous findings indicating that verbal instructional modeling (e.g., prompts) can induce placebo effects (e.g., enhanced stress reduction) via observational learning (Bajcar & Bąbel, 2018). Previous research indicates that the observer’s individual characteristics (e.g., empathy, conformity, susceptibility to social influence) can impact the emergence of placebo effects via verbal instructional modeling (Bajcar & Bąbel, 2018). Such individual characteristics, which were not measured in this study, may, therefore, underlie the unanticipated stress outcomes. They may particularly explain the larger, though non-significant, increase in stress levels displayed by the positive prompt group in comparison to the negative prompt group, from pre- to post-prompt. Future research could replicate this study taking into account individual differences in the observers’ proneness to learning from informational cues/prompts and the overall impact of prompts on stress outcomes. Albeit inconsistent with our hypotheses, these results suggest the stress-coping effects of narcissism reported in previous studies rely on the trait’s actual adaptive properties, rather than on one’s beliefs and expectations about them. This further confirms narcissism’s potential to protect against the adverse repercussions of stress.

Corroborating previous findings, narcissism did not directly predict stress (Gomes Arrulo et al., 2021; Papageorgiou et al., 2019c). Classical music preferences and habitual music uses did not moderate the relationship between narcissism and stress either (Gomes Arrulo et al., 2022). However, these findings are not consistent with empirical evidence highlighting the overall beneficial contribution of narcissism to stress management (Gomes Arrulo et al., 2021, 2022). This indicates that a certain set of conditions may need to be met for an advantageous effect to emerge. For example, it appears that different types of stressors (e.g., face-to-face vs remote) generate different effects (e.g., narcissism predicting lower stress via classical music preferences vs narcissism directly predicting lower stress) (Gomes Arrulo et al., 2021, 2022). As such, it is plausible that differences in mean stress levels between different samples could also influence the emergence of effects. This might explain the lack of significant stress outcomes observed in this study, in comparison to Gomes Arrulo et al. (2021) and Gomes Arrulo et al. (2022). Further research is needed to examine the conditions under which the positive effects of narcissism on stress occur and to identify the intricate mechanisms underlying them.

Limitations

The present study had some limitations. Although the prompts used in this study were intended to parallel information conveyed via mass media, these may have not been accurate representations of real-life media communications. Research suggests the credibility of information communicated in the media can be influenced by the emotional cues it commonly conveys (Beauvais, 2022). In fact, media communications encouraging reliance on emotions have been found to often generate greater credibility (Beauvais, 2022). The lack of emotional cues in the prompts presented in this study may have, therefore, influenced the extent to which participants believed in the information provided. Future studies could assess the impact of more credible stimuli, such as fictional news articles’ excerpts, social media posts, or short documentaries, using the present study’s methodology. Furthermore, when interpreting the IAT outcomes, it is noteworthy that these refer to participants’ relative, rather than absolute, implicit attitudes towards narcissism (Lane et al., 2007), meaning that participants’ personal beliefs may have not been accurately captured (Meissner et al., 2019). This is because the IAT examines associations between evaluative categories and target concepts based only on the comparison between two opposing concepts (in this case, ‘narcissistic personality’ and ‘non-narcissistic personality’) (Lane et al., 2007). Future research may consider incorporating recently proposed recommendations to refine the measurement and analysis of implicit attitudes via IATs, for a more accurate account of participants’ personal beliefs (see Meissner et al., 2019 for review). Additionally, the reliability coefficients for the narcissism measure were fairly low, which might help explain the lack of a significant relationship between narcissism and stress in this study. This may have resulted from the use of a short scale to measure narcissism and an insufficient sample size (Ziegler et al., 2014). The significance of our time by prompt group interaction effects on stress outcomes might have been restricted by insufficient statistical power, also resultant from a small sample size. According to a post hoc power analysis based on the effect size observed in this study for these effects, a sample of approximately 649 participants would be needed to attain statistical power at the recommended 0.80 level (Cohen, 1988). A larger sample size, however, could not be attained due to budgetary constraints which only permitted the recruitment and respective fair, non-exploitative monetary compensation of the sample used (Brown et al., 2019). It should be noted that the present study aims and methodology derived from the effects of narcissism on stress based on Gomes Arrulo et al. (2022). Therefore, the a priori power analysis conducted to compute the sample size required for this study was determined for these effects rather than for the time by prompt group interactions.

Despite these limitations, this is the first study to assess the influence of learned information on attitudes towards narcissism and its effects in the stress domain. The present outcomes demonstrate that the stereotypically negative depiction of narcissism in the media may not be representative of the general public’s perception of this trait in the context of stress. Therefore, as supported by previous research (Gomes Arrulo et al., 2021; Papageorgiou et al., 2017; Truhan et al., 2021), it may be more appropriate for media sources to feature the contextually beneficial, rather than dichotomized, nature of narcissism when disseminating information regarding this trait. Moreover, our findings encourage the further development and dissemination of research-informed recommendations on how narcissism can benefit stress management. As the public may be willing to acknowledge and avail of these recommendations, according to our findings, such further research may hold great practical value for non-clinical populations. Future studies could specifically examine whether the stress-coping potential of narcissism manifests itself when stress is measured physiologically, as opposed to via self-report. It could also assess whether this manifestation is dependent on influential factors identified in previous studies (e.g., classical music preferences, mental toughness) (Gomes Arrulo et al., 2021; Papageorgiou et al., 2019a, 2019c).

Conclusions

This study presents novel findings on the perceptions of narcissism in the context of stress. Namely, results showed that, while prompts did not influence attitudes nor stress outcomes, individuals were found to hold neutral implicit attitudes towards narcissism’s association with stress. This indicates people’s attitudes towards narcissism in the context of stress have not been deteriorated by this trait’s predominant negative depiction beyond this context. Thus, the dissemination of narcissism as an asset for stress-coping may be received with less resistance than anticipated among healthy adults. These findings inform practice in the media industry by encouraging the portrayal of narcissism in the media as contextually beneficial, rather than integrally aversive. Most importantly, however, these findings may ultimately help lessen the overall marginalization of individuals with narcissistic tendencies and encourage them to avail of this trait’s stress-coping advantages.

Data, materials and/or code availability

The datasets, data analyses files, and supplemental materials relevant to the current study are available in the OSF repository [https://osf.io/f94sm/?view_only=71428ab3c71b453fa55bc2288a69105a].

References

Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

Allen, A. P., Kennedy, P. J., Dockray, S., Cryan, J. F., Dinan, T. G., & Clarke, G. (2017). The trier social stress test: Principles and practice. Neurobiology of Stress, 6, 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2016.11.001

Baldessarini, R. J., Innamorati, M., Erbuto, D., Serafini, G., Fiorillo, A., Amore, M., Girardi, P., & Pompili, M. (2017). Differential associations of affective temperaments and diagnosis of major affective disorders with suicidal behavior. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 19–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.003

Bajcar, E. A., & Bąbel, P. (2018). How does observational learning produce placebo effects? A model integrating research findings. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2041. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02041

Bandura, A., & McClelland, D. C. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Prentice Hall.

Beauvais, C. (2022). Fake news: Why do we believe it? Joint, Bone, Spine, 89(4), 105371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2022.105371

Brown, B., Marg, L., Zhang, Z., Kuzmanović, D., Dubé, K., & Galea, J. (2019). Factors associated with payments to research participants: A review of sociobehavioral studies at a Large Southern California Research University. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 14(4), 408–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264619869538

Carpenter, T. P., Pogacar, R., Pullig, C., Kouril, M., Aguilar, S., LaBouff, J., Isenberg, N., & Chakroff, A. (2019). Survey-software implicit association tests: A methodological and empirical analysis. Behavior Research Methods, 51(5), 2194–2208. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01293-3

Carpenter, T.P., Kouril, M., Pogacar, R., Pullig, C. (2021). iatgen: IATs for Qualtrics. R package version 1.4. Available from: https://github.com/iatgen/iatgen.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences New York (p. 54). Academic.

Coleman, S. R., Pincus, A. L., & Smyth, J. M. (2019). Narcissism and stress-reactivity: A biobehavioural health perspective. Health Psychology Review, 13(1), 35–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2018.1547118

Colman, A. M. (2015). A dictionary of psychology. Oxford University Press.

Darshani, R. K. N. D. (2014). A review of personality types and locus of control as moderators of stress and conflict management. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 4(2), 1–8.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Fink, G. (Ed.). (2010). Integrative aspects of stress response. >Stress science: neuroendocrinology (pp. 323–426). Academic Press.

Fletcher, R., & Park, S. (2017). The impact of trust in the news media on online news consumption and participation. Digital Journalism, 5(10), 1281–1299. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1279979

Freestone, M., Osman, M., & Ibrahim, Y. (2020). On the uses and abuses of narcissism as a public health issue. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.70

Gimbrone, C., Rutherford, C., Kandula, S., Martínez-Alés, G., Shaman, J., Olfson, M., Gould, M. S., Pei, S., Galanti, M., & Keyes, K. M. (2021). Associations between COVID-19 mobility restrictions and economic, mental health, and suicide-related concerns in the US using cellular phone GPS and Google search volume data. PLoS ONE, 16(12), e0260931. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260931

Gomes Arrulo, T., Doumas, M., & Papageorgiou, K. (2021). Beneath the surface: The influence of music and the dark triad traits on stress and performance. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01664-0

Gomes Arrulo, T., Doumas, M., Nic an Fhirleighinn, C. & Papageorgiou, K. (2022). The influence of hip-hop/rap and narcissism on induced stress. [Under Review].

Gomes Arrulo-Clarke, T., Doumas, M., & Papageorgiou, K. (n.d.). The Dark Triad and stress in non-clinical samples: A systematic review. [Manuscript in preparation].

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464.

Hartung, J., Bader, M., Moshagen, M., & Wilhelm, O. (2021). Age and gender differences in socially aversive (“dark”) personality traits. European Journal of Personality, 0890207020988435,. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890207020988435

Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Introducing the short dark triad (SD3) a brief measure of dark personality traits. Assessment, 21(1), 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191113514105

Kaur, J. (2015). A Review of Relationship between Job Stress and Big Five Personality Dimensions among Employees of Hotel Industry. Avahan: A Journal on Hospitalty and Tourism, 3(1), 50–55.

Kelsey, R. M., Ornduff, S. R., McCann, C. M., & Reiff, S. (2001). Psychophysiological characteristics of narcissism during active and passive coping. Psychophysiology, 38(2), 292–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8986.3820292

Kilby, C. J., Sherman, K. A., & Wuthrich, V. (2018). Towards understanding interindividual differences in stressor appraisals: A systematic review. Personality and Individual Differences, 135, 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.07.001

Kirschbaum, C., Pirke, K. M., & Hellhammer, D. H. (1993). The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’–a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology, 28(1–2), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1159/000119004

Lane, K. A., Banaji, M. R., Nosek, B. A., & Greenwald, A. G. (2007). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: IV: What we know (so far) about the method.

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

Meissner, F., Grigutsch, L. A., Koranyi, N., Müller, F., & Rothermund, K. (2019). Predicting behavior with implicit measures: Disillusioning findings, reasonable explanations, and sophisticated solutions. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2483.

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Otgaar, H., & Meijer, E. (2017). The malevolent side of human nature: A meta-analysis and critical review of the literature on the dark triad (narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(2), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616666070

O’Rorke, K. (2006). Social learning theory & mass communication. ABEA Journal, 25(4), 72–74.

Oredein, T., Evans, K., & Lewis, M. J. (2020). Violent trends in hip-hop entertainment journalism. Journal of Black Studies, 51(3), 228–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934719897365

Papageorgiou, K. A., Benini, E., Bilello, D., Gianniou, F. M., Clough, P. J., & Costantini, G. (2019a). Bridging the gap: A network approach to dark triad, mental toughness, the big five, and perceived stress. Journal of Personality, 87(6), 1250–1263. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12472

Papageorgiou, K. A., Denovan, A., & Dagnall, N. (2019b). The positive effect of narcissism on depressive symptoms through mental toughness: Narcissism may be a dark trait but it does help with seeing the world less grey. European Psychiatry, 55, 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.10.002

Papageorgiou, K. A., Gianniou, F. M., Wilson, P., Moneta, G. B., Bilello, D., & Clough, P. J. (2019c). The bright side of dark: Exploring the positive effect of narcissism on perceived stress through mental toughness. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.004

Papageorgiou, K. A., Wong, B., & Clough, P. J. (2017). Beyond good and evil: Exploring the mediating role of mental toughness on the dark triad of personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.031

Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

R Core Team (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available online at https://www.R-project.org/.

Rauthmann, J. F., & Kolar, G. P. (2012). How “dark” are the Dark Triad traits? Examining the perceived darkness of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(7), 884–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.06.020

Rauthmann, J. F., & Kolar, G. P. (2013). The perceived attractiveness and traits of the Dark Triad: Narcissists are perceived as hot, Machiavellians and psychopaths not. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(5), 582–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.005

Rentfrow, P. J., & Gosling, S. D. (2003). The do re mi’s of everyday life: The structure and personality correlates of music preferences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1236. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1236

Richardson, E. N., & Boag, S. (2016). Offensive defenses: The mind beneath the mask of the dark triad traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 92, 148–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.039

Ścigała, K. A., Schild, C., Moshagen, M., Lilleholt, L., Zettler, I., Stückler, A., & Pfattheicher, S. (2021). Aversive personality and COVID-19: A first review and meta-analysis. European Psychologist, 26(4), 348. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000456

Sedikides, C., Rudich, E. A., Gregg, A. P., Kumashiro, M., & Rusbult, C. (2004). Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy?: Self-esteem matters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 400. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.400

Soliemanifar, O., Soleymanifar, A., & Afrisham, R. (2018). Relationship between personality and biological reactivity to stress: a review. Psychiatry investigation, 15(12), 1100. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2018.10.14.2

Truhan, T. E., Wilson, P., Mõttus, R., & Papageorgiou, K. A. (2021). The many faces of dark personalities: An examination of the Dark Triad structure using psychometric network analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110502

Ziegler, M., Kemper, C., & Kruyen, P. (2014). Short Scales – Five Misunderstandings and Ways to Overcome Them. Journal of Individual Differences, 35(4), 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000148

Funding

This work was supported by a Department for the Economy (DfE) PhD Studentship awarded to Teresa Gomes Arrulo-Clarke. The funding source had no direct involvement in the conduct of the research nor preparation of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Teresa Gomes Arrulo-Clarke: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization, Project Administration.

Mihalis Doumas: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration.

Kostas A. Papageorgiou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Ethics Committee at Queen’s University Belfast.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gomes Arrulo-Clarke, T., Doumas, M. & Papageorgiou, K.A. Narcissism in the context of stress: the influence of learned information on attitudes and stress outcomes. Curr Psychol 42, 31128–31140 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03922-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03922-1