Abstract

The current scientific literature lacks studies on the relationship between problematic internet use (PIU) and procrastination, especially regarding the mediating mechanisms underlying this relationship. The present study examined the association between procrastination and PIU, as well as determining the mediating roles of tolerance for ambiguity, reappraisal, and suppression. The conceptual model was tested using data collected from 434 Iranian college students. The participants completed a number of psychometric scales assessing procrastination, PIU, tolerance for ambiguity, reappraisal, and suppression. Structural equation modeling was used to test the hypothesized model. Results showed that PIU, tolerance for ambiguity, and suppression were positively associated with procrastination, and that there was a negative association between reappraisal and procrastination. Moreover, the mediation analysis indicated that tolerance for ambiguity, reappraisal, and suppression fully mediated the association between PIU and procrastination. However, it is also possible to interpret the results as suggesting that PIU is unimportant as a predictor for procrastination once mediators are controlled for.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Background

In recent years, electronic learning has been introduced into schooling and is changing the context of pedagogy with increasing access to devices, the internet, online learning environments and collaboration tools (Selwyn et al., 2017), resulting in varying degrees of integration and infusion of digital technology within schooling systems (Starkey, 2019). Online learning increased significantly in pedagogical environments when the COVID-19 pandemic impacted education globally, resulting in a move from in-person teaching to online teaching when educational institutions were forced to close (Yates et al., 2020). Moreover, increasing online activities among students is related to negative pedagogical impacts (Kandasamy et al., 2019; Geng et al., 2018). Over the past 25 years, concerns regarding PIU among young individuals have been raised (Lam et al., 2009; Simsek et al., 2019). PIU at its most extreme is considered by some to be a behavioral addiction (i.e., an addiction that does not involve the ingestion of a psychoactive substance) (Griffiths, 2005). However, since behavioral addictions may differ from drug addictions (Hellman et al., 2013), the present authors use the term ‘PIU’ rather than ‘internet addiction’ especially as leading scholars in the area have asserted that addictions on the internet (e.g., online gambling addiction) should not be considered as addictions to the internet (Griffiths, 2000) and that individuals are no more addicted to the internet than alcoholics are addicted to bottles (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2015; Griffiths & Pontes, 2014). PIU is defined as the excessive desire for internet use and comprises poor control over behaviors related to internet use, and is associated with distress and clinical impairment in daily activities (Li et al., 2019; Shaw & Black, 2008). Moreover, some argue that if ‘internet addiction’ and/or ‘PIU’ exist, it influences a relatively small percentage of online users and that what individuals on the internet are addicted to remains unclear (Widyanto et al., 2006). Therefore, PIU does not currently have an official diagnosis in diagnostic manuals, but studies have shown that PIU is related to psychological distress, which intensified during the COVID-19 outbreak and can lead to problems in academic, psychological, social, and occupational performance (Chen et al., 2022; Davis, 2001; Geng et al., 2018; Liang et al., 2022; Priego-Parra et al., 2020; Young & Rogers, 1998; Laconi et al., 2014; Young, 2016).

The risk of developing behavioral addictions, especially PIU, appears to be higher during adolescence and emerging adulthood compared with other cohorts (Grant et al., 2010; Przepiorka et al., 2019), and students appear to be one of the most affected demographic groups (Geng et al., 2018; Kandell, 1998) especially during the pandemic (Lin, 2020; Souza, 2021). However, a recent review of the prevalence of PIU during the pandemic reported there was no clear empirical evidence that it had increased during the pandemic (Burkauskas et al., 2022). Some studies have shown that in many countries, students spend more than two hours a day using the internet (Cotten & Jelenewicz, 2006; Crearie, 2014; Jones et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2017; Peng et al., 2019). If the internet is used to excess, it can have detrimental effects among a minority (Geng et al., 2018). Impacted individuals have problems with their academic performance and daily routines in comparison to students who are not impacted by their internet use (Chou & Hsiao, 2000; Kandasamy et al., 2019). Consequently, internet overuse has been associated with procrastination, which itself is associated with pedagogic problems (Geng et al., 2018; Kandemir, 2014a, b; Raiisi et al., 2018; Steel, 2007; Zhang et al., 2015).

Procrastination is defined as the deliberate delay in an action, despite being aware of its negative consequences (Klingsieck, 2013; Müller et al., 2020; Steel, 2007; Mortazavi et al., 2015; O’Brien, 2002; Van Eerde, 2003). Academic procrastination is highly prevalent among students (Schouwenburg et al., 2004; Solomon & Rothblum, 1984; Mohammadi Bytamar et al., 2017; Motie et al., 2012). In academic settings, it is very common for students to procrastinate when faced with assignments (Geng et al., 2018; Klassen et al., 2009; Lay & Silverman, 1996). One study reported that the prevalence of procrastination levels ranged from 29.2% to 47.9% among Iranian students and was similarly high in academic settings of other countries (Hayat et al., 2020a, b; Mahasneh et al., 2016; Özer et al., 2009). Therefore, procrastination should be taken seriously because of its prevalence among students (Onwuegbuzie, 2004).

Numerous studies have shown that procrastination is related to poor academic performance and low grades (Özer et al., 2009), anxiety, low self-esteem, and more generally, poor mental health (Steel, 2007). Several studies have examined the relationship between PIU and procrastination. Some studies have presented an association between PIU (including problematic social media and smartphone use) and procrastination (Hernández et al., 2019; Kandemir, 2014a, b; Lin, 2020; Przepiorka et al., 2016; Rozgonjuk et al., 2018; Şahin, 2014; Souza, 2021; Ozgonjuk et al., 2018). However, other studies have reported no significant relationship between PIU and procrastination (Odaci, 2011; Schraw et al., 2007). Therefore, the relationship between PIU and procrastination remains unclear. Despite extensive research examining PIU in Europe and the United States, little research has been done in Asia (Kljajic & Gaudreau, 2018), especially in Iran. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the structural relationship between PIU and procrastination, while considering mediating variables.

Compensatory internet use theory (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014a, b) is relevant to the present study. Compensatory internet use theory proposes that life stressors motivate some individuals to excessively use the internet as a coping strategy to help deal with their negative emotions. A number of studies have shown empirical support for compensatory internet use theory in explaining problematic smartphone use (Elhai & Contractor, 2018; Elhai et al., 2018a, b; Long et al., 2016). Compensatory internet use theory also suggests individuals with high tolerance for ambiguity (defined below) have less motivation to engage in internet use (Elhai et al., 2018a, b).

When students face a task in academic settings, they often resort to procrastination and delay the task until the last moment (Geng et al., 2018). In contrast to unpleasant academic tasks, quick access to the rewarding content in cyberspace and social networks seems to be a welcome escape for students. Coping with media exposure is one of the most important sources of goal conflict in everyday life (Reinecke & Hofmann, 2016). Moreover, engaging in online media use is actively used to delay homework and other commitments (Hinsch & Sheldon, 2013; Meier et al., 2016).

Negative emotions have been suggested as one of the antecedents of procrastination (Steel, 2007; Tice et al., 2001; Wohl et al., 2010). Evidence has shown that individuals engage in more procrastination when they are upset or sad, and that distraction reduces the negative feelings of procrastination (Tice et al., 2001). Moreover, depressed mood, neuroticism, and distressing situations have been associated with procrastination (Kınık et al., 2020; Moslemi et al., 2020). Therefore, emotion regulation plays an important role in procrastination (Sirois et al., 2019; Tice & Bratslavsky, 2000).

According to Gross et al. (2006), emotion regulation is a subset of affect regulation. Emotion regulation refers to how individuals intensify or prevent their emotions from occurring according to their goals (John & Gross, 2007; Balzarotti et al., 2010; Gross, 1998; Melka et al., 2011). The dimensions of the concept of emotion regulation comprise: (i) awareness and understanding of emotions; (ii) accepting emotions; (iii) the ability to control impulsive behaviors when experiencing negative emotions; and (iv) the ability to flexibly use emotional adjustment strategies tailored to the situation to regulate emotional responses, achieve individual goals, and meet situational demands (Amendola et al., 2019).

At the broadest level, according to Gross and John's theory of emotion regulation (2003), the present study distinguishes between antecedent-focused and response-focused emotion regulation strategies. An antecedent-focused strategy is something an individual does before their emotion response tendencies fully activate and change their behavior and peripheral physiological responses. In response-focused strategies, individuals take actions after an emotion has already begun and response tendencies have already developed. A smaller number of well-defined strategies have been studied rather than all of the many emotion regulation strategies at once. In selecting strategies for study, a number of factors were considered. The first requirement is that the methods should be ones that individuals use on a regular basis and the second requirement was that one example of each antecedent-focused and response-focused strategies should be included. A cognitive reappraisal and an expressive suppression strategy met these criteria (Gross et al., 2003). Emotion regulation strategies are categorized into two broad classes: cognitive reappraisal (an antecedent-focused strategy) and expressive suppression (a response-focused strategy) (Gross & John, 1998; John & Gross, 2007). Reappraisal is defined as changing a potentially emotional eliciting situation to reduce the emotional impact of the situation (Gross & John, 2003).

Evidence suggests that individuals who typically regulate their emotional experiences through the reappraisal strategy report more positive and fewer negative emotions. Also, they experience higher levels of psychological well-being (John & Gross, 2007). However, individuals who manage their emotions using the suppression strategy report more negative emotions, fewer positive emotions, less social support, and more depression (John & Gross, 2007; Gross & Jazaieri, 2014; Heatherton & Tice, 1994). A study in China reported that there is a relationship between individual affect, relationship satisfaction, and PIU (Zeng et al., 2021). During the pandemic, another Chinese study by Liang et al. (2021) reported that cognitive reappraisal and expression suppression were related to problematic internet use among adolescents (Liang et al., 2021). Notably, problematic users of social networking sites experience more problems with emotion regulation than non-problematic users (Hormes et al., 2014; Spada & Marino, 2017). Procrastination can be viewed as a failure of emotion regulation, which results in an individual’s desire to temporarily feel good (Sirois & Pychyl, 2013; Wypych et al., 2018). Procrastination may result from negative emotions, such as fear of failure (Haghbin et al., 2012; Schouwenburg, 1992; Schraw et al., 2007) or discomfort intolerance (Harrington, 2005). According to Blunt and Pychyl (2000), negative emotions caused by tasks are related to the avoidance of such tasks. Overall, poor emotion regulation strategies are related to procrastination via two mechanisms. First, as noted by Tice and Bratslavsky (2000), low emotion regulation skills reduce self-control, and poor self-control is associated with procrastination (Kim et al., 2017). Second, delaying assignments or tasks can be a strategy for short-term mood enhancement.

As aforementioned, the use of media and the internet can serve as a means for procrastination behaviors to temporarily reduce negative emotions and change mood in the face of difficult tasks (Reinecke & Hofmann, 2016; Zillmann, 1988). Research has shown a significant relationship between internet use and emotion regulation (Caplan, 2002, 2010; Faghani et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2021), and suggests that mood regulation can motivate many online activities (Bessière et al., 2004; LaRose et al., 2003). Based on the theory of compensatory internet use (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014a, b), internet use can be considered as a coping strategy to deal with negative emotions (Evren et al., 2019; Young, 1998).

Tolerance for ambiguity has drawn attention in recent years because of its transdiagnostic role in many disorders and mental health problems, such as anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and mood disorders. It is defined as a behavioral, cognitive, and negative emotional response to uncertainty in vague situations (Carleton, 2016; Budner, 1962; MacDonald, 1970). Tolerance for ambiguity is closely related to the intolerance of emotional distress and negative emotions (Leyro et al., 2010), and is based on the theory of compensatory internet use. Internet use can be considered a coping strategy to deal with such emotions (Faghani et al., 2020). Uncertainty intolerance is associated with internet use (Elhai et al., 2018a, b). Several studies have suggested that tolerance for ambiguity is related to problematic smartphone use (Carleton et al., 2019; He et al., 2021; Rozgonjuk, et al., 2019). A recent study among Chinese college students indicated that tolerance for ambiguity is directly and indirectly (via mediators) associated with academic procrastination (Xu & Hu, 2018). Moreover, uncertainty paralysis (i.e., a tendency to freeze during uncertainty), as one of the facets of tolerance for ambiguity, can be considered a reflection of a procrastination response to vague tasks (Haycock et al., 1998). Also, Doğanülkü et al. (2021) reported that fear of COVID-19 and intolerance of uncertainty were related to procrastination among Turkish students.

Present study hypotheses

In the review of the literature, two types of relationships have been observed regarding PIU and procrastination. Some studies have suggested procrastination as a mediator of PIU (Cui et al., 2021; Geng et al., 2018; Gong et al., 2021; Hayat et al., 2020a, b; Kandemir, 2014a, b; Thatcher et al., 2008), while others have indicated the reverse (Hernández et al., 2019; Hong et al., 2021; Reinecke et al., 2018), suggesting the direction of the relationship between PIU and procrastination is still unclear. Therefore, the first hypothesis of the present study was that there would be a direct relationship between PIU and procrastination (H1). Instead of focusing on academic goals, students may seek a source of immediate reward in internet use, and may eventually become distracted from their academic activities (Kandemir, 2014a, b). To carefully examine the relationship between PIU and procrastination, three variables (tolerance for ambiguity, suppression, and reappraisal) were examined as mediators. Therefore, the second hypothesis was that tolerance for ambiguity would mediate the relationship between PIU and procrastination (H2).

The problematic use of the internet, as a coping strategy to deal with anxiety, is related with uncertainty (Spada et al., 2008). Therefore, the third hypothesis was that reappraisal would mediate the relationship between PIU and procrastination (H3). Individuals with higher reappraisal as a desirable emotion regulation strategy experience less procrastination (Sirois et al., 2019). Moreover, the fourth hypothesis was that suppression would mediate the relationship between PIU and procrastination (H4). It is suggested that individuals turn to procrastination strategies to avoid negative emotions and experience better feelings (Baumeister et al., 1994).

Aims

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the present study is the first to study the relationship between PIU and procrastination via mediating roles of tolerance for ambiguity, reappraisal, and suppression among Iranian students. The present study analyzes two different directions of relationship between PIU and procrastination to assess which model best fits the data: (i) PIU as input and procrastination as output, and (ii) procrastination as input and PIU as output. Moreover, the study investigated whether age and gender influenced the relationship between PIU and procrastination.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kharazmi University. Participants were recruited from four universities in the cities of Tehran and Karaj (Kharazmi University, Tehran University, Shahid Beheshti University, and Sharif University of Technology). The final sample comprised 434 students with 206 males (mean age = 24.43 years, SD = 2.88 years; age range: 18–30 years) and 228 female students (mean age = 23.15 years, SD = 2.85 years; age range: 18–28 years). Overall, 30%, 28%, 27%, and 15% of the participants were studying in the faculties of Engineering, Humanities, Natural Sciences, and Mathematics, respectively. A survey including questions concerning basic demographics, procrastination, PIU, tolerance for ambiguity, reappraisal, and suppression was completed by each participant. The survey was completed offline and took approximately 30 min to complete. Before starting the survey, participants were informed about the study’s aims, and provided written informed consent. The survey’s questions were rotated in order to control order effects. Participants were assured that their information would be kept confidential and notified that they could withdraw their data before data analysis. A total of 500 surveys were distributed and 480 were returned.

Measures

Internet Addiction Test (IAT)

The 20-item IAT (Young, 1998; Young et al., 1998; Persian version: (Alavi et al., 2011) was used to assess problematic internet use. The items (e.g., “I tried to hide the time I spent on the internet from others”) are rated on a five-point scale, from 1 (not applicable) to 5 (always). Higher scores indicate a greater risk of PIU. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) showed that the Persian IAT fitted the data well (χ2/df = 1.58, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.04, and SRMR = 0.03) (Appendix Figs. 2 and 3). The internal consistency in the present study was excellent (alpha = 0.90).

Academic Procrastination Scale (APS)

The 27-item APS (Solomon & Rothblum, 1984; Persian version: Jokar & Delavarpour, 2007) was used to assess academic procrastination. The items (e.g., “To what degree do you procrastinate on this task?”) are rated on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Higher scores indicate greater procrastination. The CFA showed that the Persian APS fitted the data well (χ2/df = 2.04, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.05, and SRMR = 0.04) (Appendix Figs. 4 and 5). The internal consistency in the present study was very good (alpha = 0.82).

Multiple Stimulus Types Ambiguity Tolerance Test (MSTAT)

The 22-item MSTAT (McLain, 1993; Persian version: Abolqasemi & Narimani, 2005) was used to assess tolerance for ambiguity (TFA). The items (e.g., “I don’t tolerate ambiguous situations well”) are rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Lower scores indicate greater tolerance for ambiguity. The CFA showed that the Persian MSTAT fitted the data well (χ2/df = 1.28, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.04, and SRMR = 0.04) (Appendix Figs. 6 and 7). The internal consistency in the present study was very good (alpha = 0.88).

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ)

The 10-item ERQ (Gross & John, 2003; Persian version: Hasani, 2016) was used to assess emotion regulation. The scale comprises two dimensions: habitual expressive suppression (with four items; e.g., “I keep my emotions to myself”) and cognitive reappraisal (with six items; e.g., “When I’m faced with a stressful situation, I make myself think about it in a way that helps me stay calm”). Items are rated on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The CFA showed that the Persian ERQ fitted the data well (χ2/df = 1.49, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.04, and SRMR = 0.03) (Appendix Figs. 8 and 9). The internal consistencies for the subscales of the ERQ were very good in the present study (reappraisal α = 0.88 and suppression α = 0.84).

Design and data analysis

In the present study, structural equation modeling (Martinussen, 2010) was used to explore the structural relationships between PIU, TFA, reappraisal, suppression, and procrastination within a conceptual model. In order to identify the best model of reciprocal relationship between PIU and procrastination, the study investigated the conceptual model in two formats, considering the moderator variables. In the first model, PIU was considered as endogenous and procrastination as exogenous variable, while in the second model procrastination was taken as the endogenous variable and PIU as the exogenous variable. It should be noted that the best fit model was considered the fundamental model. In addition, the study examined whether the best-fitting model exhibited measurement invariance based on sex and age groups (18 to 24 years old and 25 to 30 years old). Commonly, measurement invariance is considered as acceptable when the changes in CFI (ΔCFI) are less than 0.01 (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002).

To do this, the data were analyzed with SPSS-24 and AMOS-24 software. Before the analyses, the assumptions of structural equation modeling were checked and obtained. Since the pattern of the missing values of the obtained data was random, cases with missing values of more than 5% were removed (Tabachnick et al., 2007; Davey & Salve, 2010). Out of 480 participants, the data of 35 individuals were detected with missing values of more than 5% of the total endorsement. Therefore, data from 445 participants were used in the analyses. Next, independent samples t-tests were used to test the extent to which there was a relationship between the missing values and the investigated variables (Davey & Savla, 2010; Ho, 2014). The results showed no systematic relationship between the missing values and other variables. Therefore, using regression-based imputation, the missing observations were replaced with a predicted score generated by multiple regression on the non-missing scores of other variables (Davey & Savla, 2010; Ho, 2014). Moreover, box plots were developed to ensure that all data remained within the first and fourth quartile boundaries. In addition, the outliers were removed using Mahalanobis distance (Meyers, et al., 2006). Because of the outlier analysis, 11 cases were treated as outliers and excluded from the final analyses. Finally, data from 434 participants were used in the final analysis.

Initially, the correlations between the research variables were calculated. To examine the theoretical model, the recommended two-step process of Anderson and Gerbing (1988) was applied. Accordingly, the reliability and validity of the present study measures were first verified using the CFA, and then, the theoretical model using structural equation modeling in AMOS software was established. A maximum likelihood estimator was used in the assumed model, and estimated the fit of the model at two levels.

In the first level, to assess model fit, more popular fitness indices, including chi-square with its degrees of freedom, comparative fit index (CFI), goodness of fit index (GFI), non-normed fit index (NNFI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used. Usually, the fit is considered good when χ2/df < 3, CFI > 0.90, GFI > 0.90, NNFI > 0.90, SRMR < 0.08, and RMSEA < 0.06 (see Hu & Bentler, 1999; Meyers et al., 2006).

In the second level, the coefficients of the model’s paths and the coefficients of determination of endogenous variables were investigated. Bootstrap analysis (iteration number = 500) was used to test the mediation model’s indirect effects’ significance level. Furthermore, exploratory factor analyses for PIU, TFA, procrastination, suppression, and reappraisal variables (based on Matsunaga's (2008) solution for item parceling one-dimensional scales) were performed. The analysis was conducted with three fixed factors and varimax rotation to select the marker variables. PIU, TFA, procrastination, suppression, and reappraisal were considered as marker variables, and the CFA assessed their unidimensionality. All the parcels were chosen as observable variables because the factor loadings were above 0.30 (see Kline, 2015). Finally, the three parcels of each variable were considered as markers (Table 1).

Results

Descriptive analyses

Table 2 presents demographic information of the study sample.

Initial analysis

Table 3 reports the kurtosis, skewness, means, standard divisions, and zero-order correlations of the present study’s variables. As shown in Table 3, lack of multicollinearity (r < 0.85) was confirmed between the variables (Kline, 2011). The prerequisite for normal distribution of kurtosis was confirmed (range − 0.34 to 1.03) as well as the variables’ skewness values (range − 0.97 to 0.55) (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2011). Results showed that PIU and TFA were positively correlated with procrastination, and the other mediating variables were significantly associated with PIU, other than for suppression and reappraisal. The three mediators were significantly associated with the exogenous variables. Moreover, an adequate fit of the measurement model (χ2 = 183.63, p < 0.001, df = 80; χ2/df = 2.29, CFI = 0.96, NFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.05, GFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.047, IFI = 0.96) was confirmed by the fit indices of a CFA. Table 4 shows the selected markers of the variables.

Testing the mediated associations

As forementioned, the study investigated whether Model 1 (PIU as endogenous and procrastination as endogenous variable) or Model 2 (procrastination as the endogenous variable and the PIU as the exogenous variable) provided the best fit for the data. The fit statistics showed that the Model 1 (χ2 = 207.27, p < 0.001, df = 80; χ2/df = 2.50, CFI = 0.95, NFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.05, GFI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.04, IFI = 0.97) indicated a good fit of the research model, whereas fit indices were weak for Model 2 (χ2 = 191.49, p < 0.001, df = 83; χ2/df = 2.31, CFI = 0.85, NFI = 0.81, RMSEA = 0.12, GFI = 0.67, SRMR = 0.34, IFI = 0.68). Therefore, the fit indices of the data in the two models indicated that the PIU as the endogenous variable fitted better than as exogenous variable. Therefore, mediated associations were carried out with respect to the PIU as endogenous.

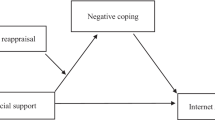

As expected, a significant χ2 value was obtained because it is easily affected by sample size, and often appears significant in large samples (Meyers et al., 2006).The current model explained 48% of the variance in procrastination scores. As shown in Table 5 and Fig. 1, the direct relationship between PIU and procrastination (β = 0.06, t = 0.84) was not significant, while tolerance for ambiguity (β = 0.40, t = 4.43), reappraisal (β = -0.34, t = -4.83), and suppression (β = 0.38, t = 4.66) predicted procrastination. Also, PIU significantly predicted tolerance for ambiguity (β = 0.31, t = 4.58), reappraisal (β = -0.36, t = -5.33), and suppression (β = 0.33, t = 4.64).

Bootstrapping

Bootstrap analysis (iteration number = 500) was performed to evaluate the mediation model. As shown in Table 6, there was a notable pathway from PIU to procrastination via TFA (β = 0.093; SE = 0.012; 95% CI ranges from 0.037 to 0.135; p < 0.05), reappraisal (β = -0.122; SE = 0.025; 95% CI ranges from -0.185 to -0.085, p < 0.05), and suppression (β = 0.125; SE = 0.018; 95% CI ranges from 0.110 to 0.129, p < 0.05). In total, the results indicated a full mediation model.

Measurement invariance of final model in sex and age groups

In order to examine the role of sex and age groups, the final model was used to assess measurement invariance (i.e., to examine the equivalence of this model across gender and age groups). The results are shown in Table 6. The change in CFI (ΔCFI) was selected as the comparative index. As shown in Table 6, the measurement invariance analyses demonstrated that invariance of final model across gender and across age group was tenable, with all ΔCFI < 0.01. In addition, all the other model fit indices (IFI, TLI, CFI, SRMR, RMSEA) met the criterion. In sum, the final model showed desirable measurement invariance based on gender and age groups (Table 7).

Discussion

The present study investigated the relationship between PIU and procrastination, which was examined with two specific objectives. First, the direct relationship between PIU and procrastination was examined, and then, their indirect relationship with the mediation of three variables (tolerance for ambiguity, reappraisal, and suppression) was examined. Four hypotheses were tested and the results indicated there was: (i) a direct relationship between PIU and procrastination; (ii) an indirect relationship between PIU and procrastination, mediated by IU; and (iii) an indirect relationship between PIU and procrastination mediated by reappraisal and suppression.

Two different directions of relationship between PIU and procrastination were analyzed to assess which model best fitted the data: (i) PIU as input and procrastination as output, and (ii) procrastination as input and PIU as output. The analysis showed that the first model was a better fit for the data. Research has shown that PIU is related to procrastination (Kandemir, 2014a, b; Thatcher et al., 2008). The results of the present study showed no direct relationship between PIU and procrastination (H1) because of the predictive power of the mediators. According to Baron and Kenny (1986) and Sobel (1982), the mediators can explain a part of or the entire relationship between two variables. Accordingly, the findings confirmed H2, H3 and H4 as well as the mediation model. However, considering the fact that because the whole relationship between PIU and procrastination was mediated by other variables, another interpretation is that if the mediators were controlled for, the relationship disappeared and it is possible that the role of PIU as a predictor of procrastination was non-significant. Notably, the majority of previous studies have considered procrastination as a predictor of PIU (e.g., Hernández et al., 2019; Şahin, 2014). However, the present results indicated the possibility of predominance of PIU over procrastination via an indirect relationship.

According to H2, the relationship between PIU and procrastination would be mediated by tolerance for ambiguity. High levels of social anxiety are associated with high levels of tolerance for ambiguity (Boelen & Reijntjes, 2009; Carleton, 2012; Carleton et al., 2010) and social avoidance (Miers et al., 2014). Therefore, tolerance for ambiguity is associated with an individual’s preference for online social interaction. Also, social anxiety has been associated with problematic smartphone use (Wolniewicz et al., 2018) and non-social smartphone use (Elhai et al., 2017).

The findings of the present study also support the relationship between tolerance for ambiguity and procrastination. Faced with difficult and ambiguous assignments, students may experience uncertainty paralysis, a subset of tolerance for ambiguity, procrastinating instead of completing homework (Haycock et al., 1998). The findings also supported that suppression and reappraisal mediated the relationship between PIU and procrastination. Accordingly, self-regulatory executive function theory (Wells & Matthews, 1996) states that acute addictive behaviors are related to negative metacognitive beliefs concerning non-controllability, self-doubt, maladaptive coping strategies, and further poor metacognitive strategies (Spada, 2015), which eventually cause psychological and behavioral disorders. PIU is associated with negative emotions (Cheng & Li, 2014) among individuals who use procrastination to regulate their negative emotions to temporarily avoid negative emotions and experience better feelings (Baumeister et al., 1994) by increasing short-term pleasure and reducing short-term pain (Gross & Jazaieri, 2014; Tamir, 2009). Experiencing short-term pleasure is the motivation that relates to procrastination as a way to regulate dysfunctional emotions. The results of the present study also showed that reappraisal was inversely related to procrastination. Individuals who re-evaluate their stressors and problems reduce their negative emotions (Finlay-Jones, 2017), and reduce the likelihood of engaging in procrastination (Sirois et al., 2019).

The results showed measurement invariance of the current model across gender and age groups, indicating that there were no differences across ages and gender in the current model. Therefore, gender and age do not influence the relationship between PIU and procrastination. More broadly, the results of the present study provide some support for the compensatory internet use theory (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014a, b), which posits that some individuals regulate their negative emotions by using the internet problematically. Individuals who score high on tolerance for ambiguity spend many hours on the internet to reduce the severity of their ambiguity and anxiety (Spada et al., 2008). According to Young (1998), PIU can occur when individuals use the internet to cope with difficult life situations, such as exams and academic tasks. According to Young (1998), internet use has a propensity to be used to cope with or compensate for real life problems. In later works, Caplan and High (2011) also suggested that through the exchange of online messages, individuals compensate for what they may lack in real life. According to compensatory internet use theory, negative life situations can motivate internet users to spend time online to alleviate negative emotions (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014a, b). As a result of social stimulation, the individual feels better. It is an understandable and practical way to acquire social stimulation when there is a lack of it (e.g., Chappell et al., 2006), but this habit may sometimes be associated with negative consequences such as procrastination due to the amount of compensation required to regulate negative feelings.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, the study sample was selected from Iranian universities, and mainly included students living in dormitories. Therefore, the results of this research cannot be generalized to all students or to those from other countries. Second, from the perspective of the social-cognitive models of media use, it is difficult to distinguish between problematic and addictive use of the internet because of the widespread use of the internet and social networks. Therefore, spending many hours on the internet is not necessarily problematic (LaRose & Eastin, 2004; LaRose et al., 2010; Tokunaga, 2017). Third, data were collected using self-report instruments, potentially leading to biased or distorted responses. Fourth, some control variables such as mental health and life stress were not assessed in the present study. Fifth, the IAT was used to determine PIU which might not be an effective tool in comparison with other PIU scales (such as the IDS-15 developed by Pontes et al., 2017). However, the IAT is the psychometric scale most used in Iran. Finally, the cross-sectional design employed does not allow for definitive statements of causality. Furthermore, because of full mediation, if mediators were controlled, the relationship between PIU and procrastination disappeared, therefore, it is not clear if tolerance for ambiguity, reappraisal, and suppression are mediators or control variables. Longitudinal analyses might provide further insight on the issue, but it is impossible to definitively conclude that the results of the present study support the importance of the PIU construct given that it is limited by the cross-sectional nature of the data.

Conclusion

The results of the present study expand on the findings of previous studies in explaining the relationship between PIU and procrastination, and explained the underlying constructs of students’ procrastination. Suppression, reappraisal, and tolerance for ambiguity mediated the relationship between PIU and procrastination, offering a more nuanced explanation of this relationship than previous research.

References

Abolqasemi A, & Narimani M. (2005). Psychological tests [in Persian]. Ardebil:Razvand Bagh Publishing, 13(7), 10–17. [Persian].

Alavi, S. S., Jannatifard, F., Eslami, M., & Rezapour, H. (2011). Survey on validity and reliability of diagnostic questionnaire of internet addiction disorder in students users. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 13(7), 34–37.

Amendola, S., Spensieri, V., Guidetti, V., & Cerutti, R. (2019). The relationship between difficulties in emotion regulation and dysfunctional technology use among adolescents. Journal of Psychopathology, 25(1), 10–17.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411.

Balzarotti, S., John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2010). An Italian adaptation of the emotion regulation questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(1), 61–67.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2), 243.

Bessière, K., Kiesler, S., Kraut, R., & Boneva, B. (2004). Longitudinal effects of internet uses on depressive affect: A social resources approach. Unpublished Manuscript, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA

Blunt, A. K., & Pychyl, T. A. (2000). Task aversiveness and procrastination: A multi-dimensional approach to task aversiveness across stages of personal projects. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(1), 153–167.

Boelen, P. A., & Reijntjes, A. (2009). Intolerance of uncertainty and social anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(1), 130–135.

Budner, S. (1962). Intolerance of ambiguity as a personality variable. Journal of Personality, 30, 29–50.

Burkauskas, J., Gecaite-Stonciene, J., Demetrovics, Z., Griffiths, M. D., & Király, O. (2022). Prevalence of problematic internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 46, 101179.

Caplan, S. E. (2002). Problematic Internet use and psychosocial well-being: Development of a theory-based cognitive–behavioral measurement instrument. Computers in Human Behavior, 18(5), 553–575.

Caplan, S. E. (2010). Theory and measurement of generalized problematic Internet use: A two-step approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 1089–1097.

Caplan, S. E., & High, A. C. (2011). Online social interaction, psychosocial well-being, and problematic Internet use. In K. S. Young & C. N. de Abreu (Eds.), Internet addiction: A handbook and guide to evaluation and treatment (pp. 35–53). Wiley.

Carleton, R. N. (2012). The intolerance of uncertainty construct in the context of anxiety disorders: Theoretical and practical perspectives. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 12(8), 937–947.

Carleton, R. N. (2016). Into the unknown: A review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 39, 30–43.

Carleton, R. N., Collimore, K. C., & Asmundson, G. J. (2010). “It’s not just the judgements—It’s that I don’t know”: Intolerance of uncertainty as a predictor of social anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24(2), 189–195.

Carleton, R. N., Desgagné, G., Krakauer, R., & Hong, R. Y. (2019). Increasing intolerance of uncertainty over time: The potential influence of increasing connectivity. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 48(2), 121–136.

Chappell, D., Eatough, V., Davies, M. N., & Griffiths, M. (2006). EverQuest—It’s just a computer game right? An interpretative phenomenological analysis of online gaming addiction. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 4(3), 205–216.

Chen, C. Y., Chen, I. H., Hou, W. L., Potenza, M. N., O’Brien, K. S., Lin, C. Y., & Latner, J. D. (2022). The relationship between children’s problematic internet-related behaviors and psychological distress during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 16(2), e73.

Cheng, C., & Li, A. Y. L. (2014). Internet addiction prevalence and quality of (real) life: A meta-analysis of 31 nations across seven world regions. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(12), 755–760.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255.

Chou, C., & Hsiao, M. C. (2000). Internet addiction, usage, gratification, and pleasure experience: The Taiwan college students’ case. Computers & Education, 35(1), 65–80.

Cotten, S. R., & Jelenewicz, S. M. (2006). A disappearing digital divide among college students? Peeling away the layers of the digital divide. Social Science Computer Review, 24(4), 497506.

Crearie, L. (2014). 21st century learning spaces and online residency: just how much time do students spend online? In: Morris, L. & Tsolakidis, C. (Eds.), International Conference on Information Communication Technologies in Education 2014 Proceedings (pp. 146–153). Kos, Greece: International Conference on Information Communication Technologies in Education.

Cui, G., Yin, Y., Li, S., Chen, L., Liu, X., Tang, K., & Li, Y. (2021). Longitudinal relationships among problematic mobile phone use, bedtime procrastination, sleep quality and depressive symptoms in Chinese college students: A cross-lagged panel analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 449.

Davey, A., & Savla, J. (2010). Statistical power analysis with missing data: A structural equation modeling approach. Routledge.

Davis, R. A. (2001). A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 17(2), 187195.

Doğanülkü, H. A., Korkmaz, O., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2021). Fear of COVID-19 lead to procrastination among Turkish university students: The mediating role of intolerance of uncertainty. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 178.

Elhai, J. D., & Contractor, A. A. (2018). Examining latent classes of smartphone users: Relations with psychopathology and problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 82, 159–166.

Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C., Dvorak, R. D., & Hall, B. J. (2017). Non-social features of smartphone use are most related to depression, anxiety and problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 75–82.

Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C., O’Brien, K. D., & Armour, C. (2018a). Distress tolerance and mindfulness mediate relations between depression and anxiety sensitivity with problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 477–484.

Elhai, J. D., Tiamiyu, M. F., Weeks, J. W., Levine, J. C., Picard, K. J., & Hall, B. J. (2018b). Depression and emotion regulation predict objective smartphone use measured over one week. Personality and Individual Differences, 133, 21–28.

Evren, C., Evren, B., Dalbudak, E., Topcu, M., Kutlu, N., & Elhai, J. D. (2019). Severity of dissociative experiences and emotion dysregulation mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and Internet addiction symptom severity among young adults. Düşünen Adam: The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 32(4), 334–344.

Faghani, N., Akbari, M., Hasani, J., & Marino, C. (2020). An emotional and cognitive model of problematic Internet use among college students: The full mediating role of cognitive factors. Addictive Behaviors, 105, 106252.

Finlay-Jones, A. L. (2017). The relevance of self-compassion as an intervention target in mood and anxiety disorders: A narrative review based on an emotion regulation framework. Clinical Psychologist, 21(2), 90103.

Gámez-Guadix, M., Calvete, E., Orue, I., & Las Hayas, C. (2015). Problematic Internet use and problematic alcohol use from the cognitive–behavioral model: A longitudinal study among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 40, 109–114.

Geng, J., Han, L., Gao, F., Jou, M., & Huang, C. C. (2018). Internet addiction and procrastination among Chinese young adults: A moderated mediation model. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 320–333.

Gong, Z., Wang, L., & Wang, H. (2021). Perceived stress and internet addiction among chinese college students: Mediating effect of procrastination and moderating effect of flow. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2290.

Grant, J. E., Potenza, M. N., Weinstein, A., & Gorelick, D. A. (2010). Introduction to behavioral addictions. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(5), 233–241.

Griffiths, M. D. (2000). Internet addiction - Time to be taken seriously? Addiction Research, 8, 413–418.

Griffiths, M. D. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197.

Griffiths, M. D., & Pontes, H. M. (2014). Internet addiction disorder and internet gaming disorder are not the same. Journal of Addiction Research and Therapy, 5, e124.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (1998). Mapping the domain of expressivity: Multimethod evidence for a hierarchical model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 170–191.

Gross, J. J., & Jazaieri, H. (2014). Emotion, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: An affective science perspective. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(4), 387–401.

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348.

Gross, J. J., Richards, J. M., & John, O. P. (2006). Emotion regulation in everyday life. In D. K. Snyder, J. Simpson, & J. N. Hughes (Eds.), Emotion regulation in couples and families: Pathways to dysfunction and health (pp. 13–35). American Psychological Association.

Haghbin, M., McCaffrey, A., & Pychyl, T. A. (2012). The complexity of the relation between fear of failure and procrastination. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 30(4), 249–326.

Harrington, N. (2005). It’s too difficult! Frustration intolerance beliefs and procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(5), 873–883.

Hasani, J. (2016). Persian version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Factor structure, reliability and validity. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 10(3), 156–161.

Hayat, A. A., Jahanian, M., Bazrafcan, L., & Shokrpour, N. (2020a). Prevalence of academic procrastination among medical students and its relationship with their academic achievement. Shiraz E-Medical Journal, 21(7), e96049.

Hayat, A. A., Kojuri, J., & Mitra Amini, M. D. (2020b). Academic procrastination of medical students: The role of Internet addiction. Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism, 8(2), 83–89.

Haycock, L. A., McCarthy, P., & Skay, C. L. (1998). Procrastination in college students: The role of self-efficacy and anxiety. Journal of Counseling & Development, 76(3), 317–324.

He, X., Zhang, Y., Chen, M., Zhang, J., Zou, W., & Luo, Y. (2021). Media exposure to covid-19 predicted acute stress: A moderated mediation model of intolerance of uncertainty and perceived social support. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 1552.

Heatherton, T., & Tice, D. M. (1994). Losing control: How and why people fail at self-regulation. Academic Press.

Hellman, M., Schoenmakers, T. M., Nordstrom, B. R., & Van Holst, R. J. (2013). Is there such a thing as online video game addiction? A cross-disciplinary review. Addiction Research & Theory, 21(2), 102–112.

Hernández, C., Ottenberger, D. R., Moessner, M., Crosby, R. D., & Ditzen, B. (2019). Depressed and swiping my problems for later: The moderation effect between procrastination and depressive symptomatology on internet addiction. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 1–9.

Hinsch, C., & Sheldon, K. M. (2013). The impact of frequent social internet consumption: Increased procrastination and lower life satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 12(6), 496–505.

Ho, R. (2014). Handbook of univariate and multivariate data analysis and interpretation with SPSS. CRC Press.

Hong, W., Liua, R. D., Ding, Y., Jiang, S., Yang, X., & Sheng, X. (2021). Academic procrastination precedes problematic mobile phone use in Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal mediation model of distraction cognitions. Addictive Behaviors, 121, 106993.

Hormes, J. M., Kearns, B., & Timko, C. A. (2014). Craving Facebook? Behavioral addiction to online social networking and its association with emotion regulation deficits. Addiction, 109(12), 2079–2088.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Individual differences in emotion regulation. Handbook of emotion regulation. Guilford, 351–372.

Jokar, B., & Delavarpour, M. (2007). Relationship between educational procrastination and development objectives [in Persian]. Modern Educational Ideas, 3(3), 8–61.

Jones, S., Johnson-Yale, C., Millermaier, S., & Pérez, F. S. (2009). US college students’ internet use: Race, gender and digital divides. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14(2), 244–264.

Kandasamy, S., Abdulrahuman, M. B., & Shyamala, J. (2019). A study on anxiety disorder among college students with internet addiction. VHL Regional Portal (Preprint). https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/sea-201171

Kandell, J. J. (1998). Internet addiction on campus: The vulnerability of college students. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1(1), 11–17.

Kandemir, M. (2014a). Predictors of academic procrastination: Coping with stress, internet addiction and academic motivation. World Applied Sciences Journal, 32(5), 930–938.

Kandemir, M. (2014b). Reasons of academic procrastination: Self-regulation, academic self-efficacy, life satisfaction and demographics variables. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 152, 188193.

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014a). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351354.

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014b). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354.

Kim, J., Hong, H., Lee, J., & Hyun, M. H. (2017). Effects of time perspective and self-control on procrastination and internet addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(2), 229–236.

Kınık, Ö., & Odacı, H. (2020). Effects of dysfunctional attitudes and depression on academic procrastination: Does self-esteem have a mediating role? British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 48(5), 638–649.

Klassen, R. M., Ang, R. P., Chong, W. H., Krawchuk, L. L., Huan, V. S., Wong, I. Y., & Yeo, L. S. (2009). A cross-cultural study of adolescent procrastination. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19(4), 799–811.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3th ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Klingsieck, K. B. (2013). Procrastination in different life-domains: Is procrastination domain specific? Current Psychology, 32(2), 175–185.

Kljajic, K., & Gaudreau, P. (2018). Does it matter if students procrastinate more in some courses than in others? A multilevel perspective on procrastination and academic achievement. Learning and Instruction, 58, 193–200.

Laconi, S., Rodgers, R. F., & Chabrol, H. (2014). The measurement of internet addiction: A critical review of existing scales and their psychometric properties. Computers in Human Behavior, 41, 190202.

Lam, L. T., Peng, Z. W., Mai, J. C., & Jing, J. (2009). Factors associated with internet addiction among adolescents. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 12(5), 551–555.

LaRose, R., Kim, J., & Peng, W. (2010). Social networking: Addictive, compulsive, problematic, or just another media habit? In A networked self (pp. 67–89). Routledge.

LaRose, R., & Eastin, M. S. (2004). A social cognitive theory of internet uses and gratifications: Toward a new model of media attendance. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 48(3), 358–377.

LaRose, R., Lin, C. A., & Eastin, M. S. (2003). Unregulated internet usage: Addiction, habit, or deficient self-regulation? Media Psychology, 5(3), 225253.

Lay, C., & Silverman, S. (1996). Trait procrastination, anxiety, and dilatory behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 21(1), 61–67.

Lee, C., & Kim, O. (2017). Predictors of online game addiction among Korean adolescents. Addiction Research & Theory, 25(1), 58–66.

Leyro, T. M., Zvolensky, M. J., & Bernstein, A. (2010). Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: A review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychological Bulletin, 136(4), 576.

Li, Q., Dai, W., Zhong, Y., Wang, L., Dai, B., & Liu, X. (2019). The mediating role of coping styles on impulsivity, behavioral inhibition/approach system, and internet addiction in adolescents from a gender perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2402.

Liang, L., Li, C., Meng, C., Guo, X., Lv, J., Fei, J., & Mei, S. (2022). Psychological distress and internet addiction following the COVID-19 outbreak: Fear of missing out and boredom proneness as mediators. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 40, 8–14.

Liang, L., Zhu, M., Dai, J., Li, M., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The mediating roles of emotional regulation on negative emotion and internet addiction among Chinese adolescents from a development perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 608317.

Lin, M. P. (2020). Prevalence of internet addiction during the COVID-19 outbreak and its risk factors among junior high school students in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8547.

Long, J., Liu, T. Q., Liao, Y. H., Qi, C., He, H. Y., Chen, S. B., & Billieux, J. (2016). Prevalence and correlates of problematic smartphone use in a large random sample of Chinese undergraduates. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 408.

MacDonald, A. P. (1970). Revised scale for ambiguity tolerance: Reliability and validity. Psychological Reports, 26(3), 791798.

Mahasneh, A. M., Bataineh, O. T., & Al-Zoubi, Z. H. (2016). The relationship between academic procrastination and parenting styles among Jordanian undergraduate university students. The Open Psychology Journal, 9(1), 25–34.

Martinussen, T. (2010). Dynamic path analysis for event time data: Large sample properties and inference. Lifetime Data Analysis, 16(1), 85–101.

Matsunaga, M. (2008). Item parceling in structural equation modeling: A primer. Communication Methods and Measures, 2(4), 260–293.

McLain, D. L. (1993). The MSTA-1: A new measure of an individual’s tolerance for ambiguity. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53, 183189.

Meier, A., Reinecke, L., & Meltzer, C. E. (2016). “Facebocrastination”? Predictors of using Facebook for procrastination and its effects on students’ well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 6576.

Melka, S. E., Lancaster, S. L., Bryant, A. R., & Rodriguez, B. F. (2011). Confirmatory factor and measurement invariance analyses of the emotion regulation questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(12), 12831293.

Meyers, L. S., Gamst, G., & Guarino, A. J. (2006). Applied multivariate research: Design and interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Miers, A. C., Blöte, A. W., Heyne, D. A., & Westenberg, P. M. (2014). Developmental pathways of social avoidance across adolescence: The role of social anxiety and negative cognition. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(8), 787794.

Mohammadi Bytamar, J., Zenoozian, S., Dadashi, M., Saed, O., Hemmat, A., & Mohammadi, G. (2017). Prevalence of academic procrastination and its association with metacognitive beliefs in Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Journal of Medical Education Development, 10(27), 84–97.

Mortazavi, F., Mortazavi, S. S., & Khosrorad, R. (2015). Psychometric properties of the Procrastination Assessment Scale-Student (PASS) in a student sample of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 17(9), e28328.

Moslemi, Z., Ghomi, M., & Mohammadi, D. (2020). The relationship between personality dimensions (neuroticism, conscientiousness) and Self-esteem with Academic procrastination among students at Qom University of Medical Sciences. Development Strategies in Medical Education, 7(1), 5–16.

Motie, H., Heidari, M., & Sadeghi, M. A. (2012). Predicting academic procrastination during self-regulated learning in Iranian first grade high school students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69(24), 22992308.

Müller, S. M., Wegmann, E., Stolze, D., & Brand, M. (2020). Maximizing social outcomes? Social zapping and fear of missing out mediate the effects of maximization and procrastination on problematic social networks use. Computers in Human Behavior, 107, 106296.

O’Brien, W. K. (2002). Applying the transtheoretical model to academic procrastination. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 62(11-B), 5359.

Odaci, H. (2011). Academic self-efficacy and academic procrastination as predictors of problematic internet use in university students. Computers & Education, 57(1), 11091113.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Academic procrastination and statistics anxiety. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 29(1), 3–19.

Özer, B. U., Demir, A., & Ferrari, J. R. (2009). Exploring academic procrastination among Turkish students: Possible gender differences in prevalence and reasons. Journal of Social Psychology, 149(2), 241–257.

Ozgonjuk, D., Kattago, M., & Täht, K. (2018). Social media use in lectures mediates the relationship between procrastination and problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 191198.

Peng, W., Zhang, X., & Li, X. (2019). Using behavior data to predict the internet addiction of college students. In: International Conference on Web Information Systems and Applications (pp. 151–162). Springer, Cham.

Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). The development and psychometric evaluation of the Internet Disorder Scale (IDS-15). Addictive Behaviors, 64, 261–268.

Priego-Parra, B. A., Triana-Romero, A., Pinto-Gálvez, S. M., Ramos, C. D., Salas-Nolasco, O., Reyes, M. M., ..., & Remes-Troche, J. M. (2020). Anxiety, depression, attitudes, and internet addiction during the initial phase of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic: A cross-sectional study in México. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.10.20095844

Przepiorka, A., Blachnio, A., & Cudo, A. (2019). The role of depression, personality, and future time perspective in internet addiction in adolescents and emerging adults. Psychiatry Research, 272, 340348.

Przepiorka, A., Błachnio, A., & Díaz-Morales, J. F. (2016). Problematic Facebook use and procrastination. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 5964.

Raiisi, F., & Riyassi, M. (2018). Predicting the rate of procrastination of university students based on internet addiction and metaphorical perception of time during the Corona virus outbreak. Shenakht Journal of Psychology and Psychiatry, 9, 73–83.

Reinecke, L., & Hofmann, W. (2016). Slacking off or winding down? An experience sampling study on the drivers and consequences of media use for recovery versus procrastination. Human Communication Research, 42(3), 441–461.

Reinecke, L., Meier, A., Beutel, M. E., Schemer, C., Stark, B., Wölfling, K., & Müller, K. W. (2018). The relationship between trait procrastination, internet use, and psychological functioning: Results from a community sample of German adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 913.

Rozgonjuk, D., Elhai, J. D., Täht, K., Vassil, K., Levine, J. C., & Asmundson, G. J. (2019). Non-social smartphone use mediates the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and problematic smartphone use: Evidence from a repeated-measures study. Computers in Human Behavior, 96, 5662.

Rozgonjuk, D., Kattago, M., & Täht, K. (2018). Social media use in lectures mediates the relationship between procrastination and problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 191198.

Şahin, Y. L. (2014). Comparison of users’ adoption and use cases of Facebook and their academic procrastination. Digital Education Review, 25, 127–138.

Schouwenburg, H. C. (1992). Procrastinators and fear of failure: An exploration of reasons for procrastination. European Journal of Personality, 6(3), 225236.

Schouwenburg, H. C. (2004). Procrastination in academic settings: General introduction. In H. C. Schouwenburg, C. H. Lay, T. A. Pychyl, & J. R. Ferrari (Eds.), Counseling the procrastinator in academic settings. American Psychological Association (pp. 3–17). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Schraw, G., Wadkins, T., & Olafson, L. (2007). Doing the things we do: A grounded theory of academic procrastination. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 12–25.

Selwyn, N., Nemorin, S., Bulfin, S., & Johnson, N. (2017). Left to their own devices: The everyday realities of one-to-one classrooms. Oxford Review of Education, 43(3), 289–310.

Shaw, M., & Black, D. W. (2008). Internet addiction. CNS Drugs, 22(5), 353–365.

Simsek, N., Sahin, D., & Evli, M. (2019). Internet addiction, cyberbullying, and victimization relationship in adolescents: a sample from Turkey. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 30(3), 201–210.

Sirois, F. M., Nauts, S., & Molnar, D. S. (2019). Self-compassion and bedtime procrastination: An emotin regulation perspective. Mindfulness, 10(3), 434445.

Sirois, F., & Pychyl, T. (2013). Procrastination and the priority of short-term mood regulation: Consequences for future self. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(2), 115–127.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312.

Solomon, L. J., & Rothblum, E. D. (1984). Academic procrastination: Frequency and cognitive-behavioral correlates. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31(4), 503.

Souza, M. C. R. (2021). Online self-regulated learning, academic stress, academic procrastination and the moderating role of social support in predicting internet addiction among university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 602904.

Spada, M. M. (2015). Commentary on: Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 124–125.

Spada, M. M., Langston, B., Nikčević, A. V., & Moneta, G. B. (2008). The role of metacognitions in problematic internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(5), 23252335.

Spada, M. M., & Marino, C. (2017). Metacognitions and emotion regulation as predictors or problematic internet use in adolscents. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 14(1), 59–63.

Starkey, L. (2019). Three dimensions of student-centred education: A framework for policy and practice. Critical Studies in Education, 60(3), 375–390.

Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65–94.

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., & Ullman, J. B. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (vol. 5, pp. 481–498). Pearson.

Tamir, M. (2009). What do people want to feel and why? Pleasure and utility in emotion regulation. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(2), 101105.

Thatcher, A., Wretschko, G., & Fridjhon, P. (2008). Online flow experiences, problematic internet use and internet procrastination. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(5), 22362254.

Tice, D. M., & Bratslavsky, E. (2000). Giving in to feel good: The place of emotion regulation in the context of general self-control. Psychological Inquiry, 11(3), 149159.

Tice, D. M., Bratslavsky, E., & Baumeister, R. F. (2001). Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: If you feel bad, do it! Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(1), 53–67.

Tokunaga, R. S. (2017). A meta-analysis of the relationships between psychosocial problems and internet habits: Synthesizing internet addiction, problematic internet use, and deficient self-regulation research. Communication Monographs, 84(4), 423446.

Van Eerde, W. (2003). A meta-analytically derived nomological network of procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(6), 14011418.

Wells, A., & Matthews, G. (1996). Modelling cognition in emotional disorder: The S-REF model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(11–12), 881–888.

Widyanto, L., & Griffiths, M. (2006). ‘Internet addiction’: A critical review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 4(1), 31–51.

Wohl, M. J., Pychyl, T. A., & Bennett, S. H. (2010). I forgive myself, now I can study: How self-forgiveness for procrastinating can reduce future procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(7), 803808.

Wolniewicz, C. A., Tiamiyu, M. F., Weeks, J. W., & Elhai, J. D. (2018). Problematic smartphone use and relations with negative affect, fear of missing out, and fear of negative and positive evaluation. Psychiatry Research, 262, 618–623.

Wypych, M., Matuszewski, J., & Dragan, W. Ł. (2018). Roles of impulsivity, motivation, and emotion regulation in procrastination–Path analysis and comparison between students and non-students. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 891.

Xu, T., & Hu, P. (2018). A Serial Mediation Model between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Academic Procrastination. Renmin University of China Education Journal, 58(6), 103450.

Yates, A., Starkey, L., Egerton, B., & Flueggen, F. (2020). High school students’ experience of online learning during Covid-19: The influence of technology and pedagogy. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 30(1), 59–73.

Young, K. S. (1998). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 1(3), 237244.

Young, K. (2016). Internet Addiction Test (IAT). Wood Dale, IL: Stoelting.

Young, K. S., & Rogers, R. C. (1998). The relationship between depression and internet addiction. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1(1), 25–28.

Zeng, G., Zhang, L., Fung, S. F., Li, J., Liu, Y. M., Xiong, Z. K., ..., & Huang, Q. (2021). Problematic internet usage and self-esteem in chinese undergraduate students: the mediation effects of individual affect and relationship satisfaction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6949.

Zhang, Y., Mei, S., Li, L., Chai, J., Li, J., & Du, H. (2015). The relationship between impulsivity and internet addiction in Chinese college students: A moderated mediation analysis of meaning in life and self-esteem. PloS One, 10(7), e0131597.

Zillmann, D. (1988). Mood management through communication choices. American Behavioral Scientist, 31(3), 327340.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The data supporting this study's findings are available on request from the first author [Email address: javad73.june@gmail.com]. The data are not publicly available due to containing information that could compromise research participant privacy/consent.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Appendix 5

Appendix 6

Appendix 7

Appendix 8

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Emadi Chashmi, S.J., Hasani, J., Kuss, D.J. et al. Tolerance for ambiguity, reappraisal, and suppression mediate the relationship between problematic internet use and procrastination. Curr Psychol 42, 27088–27109 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03745-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03745-0