Abstract

Purpose: To investigate the structure of spirituality among teenagers, who live in a secular country, employing a QoL assessment, the EORTC QLQ-SWB32. Methods: Japanese high-school students, 15 to 17 years of age, answered EORTC QLQ-SWB32, which had 5 scales: Relationships with Others, Relationship with Self (RS), Existential, Relationship with Someone or Something Greater (RSG), and Change. It had “skip” items 22 and 23 (score range:0–200), which distinguished non-believers (score:0), light believers (score:33–66), and deep believers (score:100–200). Cronbach’s alpha and principal component analysis (PCA) were investigated. Correlations between item-32 (global spiritual well-being (SWB)) scores and 5 scale-scores were estimated. Global SWB scores were compared among groups via one-way ANOVA. Results: Among 283 male students, there were 142 non-believers (50%), 98 light believers (35%), and 43 deep believers (15%). Cronbach’s alpha values of the five scales were above 0.7 for deep believers. However, RSG did not show internal consistency for non-believers and light believers. PCA showed that the RSG items constructed a RSG scale for deep believers but did not make any scale for non-believers and light believers. The correlation coefficients between global SWB and RSG increased in order of non-believers (r = 0.295), light believers (r = 0.399), and deep believers (r = 0.559). RS correlated with global SWB in non-believers and light believers (r<- 0.4). Among groups, light believers had significantly better global SWB than non-believers and deep believers (p = 0.0312). Conclusion: The structure of spirituality among high-school students differs depending on RSG. And RS might be critical for students without sense of RSG. Trial registration number: This observation study was retrospectively registered on 2nd November 2021 (UMIN 000045962).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The recent investigation of spirituality is the result of recognizing spiritual care as an important aspect of health care, particularly supportive and/or palliative care for cancer (Best et al., 2015; Phelps et al., 2012). Studies on spirituality were mainly performed using narrative methods (Yonker et al., 2012). Then spiritual studies that focus on people with advanced cancer and those in end-of-life stages have employed quality of life (QoL) assessments (Ferrell et al., 1995; Kyranou & Nicolaou, 2021; Peterman et al., 2002; Rohde et al., 2019). Spirituality in serious illness and health has been reviewed recently (Balboni et al., 2022). While studies have investigated relationships between spirituality/religiousness and QoL for healthy adults, resulting in positive effects of spirituality/religiousness on some QoL scales, such as mental well-being and social well-being (Borges et al., 2021; Vitorino et al., 2018; WHOQOL SRPB Group, 2006). Various studies have also reported the association between spirituality/religiousness and improved health outcomes for people including young individuals, indicating that religiosity/spirituality positively affect adolescent health (Vitorino et al., 2018; Zidkova et al., 2020). However, there have been only a few reports describing association between spiritual structures of healthy youngsters and religiousness via spiritual modules of QoL assessments (Abdel-Khalek, 2010; Tavel et al., 2022; Vitorino et al., 2018).

The EORTC Study Group on Quality of Life (EORTC QLG) began to investigate SWB in the 1990s (Ahlner-Elmqvist & Kaasa, 1998). Literature reviews regarding the measures identified were systematically conducted twice in two stages (1996–2001 and 2001–2007) in accordance with Phase 1 testing, which was defined in the QLG guidelines for module development comprising four phases (Johnson et al., 2011; Vivat, 2008). Further, 84 relevant issues were identified and grouped into three domains: relationship with self and others (29 issues), existential (24 issues), and religious (31 issues) (Vivat, 2008). Through interviews held in Phase 2 testing of the QLG guidelines, the interviewees suggested the addition of 6 new issues (Vivat, 2008). By the end of Phase 3 A testing, these 90 issues were reduced to 38 items on the basis of missing data, prevalence, correlations, and participants’ comments (Vivat et al., 2013). The 38-item version was developed by employing people from Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Iceland, Italy, Netherlands, and the UK. These regions are considered to have many religious people. Indeed, of the 39 people enrolled in Phase 1–3 A, there were 32 religious people (Vivat et al., 2013).

Japanese ancients believed in polytheism, which was the origin of Shintoism. In the 6th century, Buddhism was introduced to Japan and became well established until the 15th century. However, provincial wars between the 15th and 16th centuries led to the downfall of Buddhism. Although Christianity was introduced to Japan in the 16th century, it was prohibited during the Edo period from the 17th century to the 19th century. Furthermore, the Edo shogunate used Buddhist temples as children’s schools and city offices to manage residents, resulting in a weakened religious atmosphere. In the 19th century, the Meiji government promoted the separation of Buddhism and Shintoism, and Shintoism was valued until the end of World War II. Since 1945, religious liberty has been guaranteed by the Constitution. It depends on individuals whether they believe in God or something greater than themselves. Recently, industrial modernization has promoted a reasonable way of thinking even in religious matters. Consequently, not many Japanese people strongly believe in God or something greater than themselves. For example, they visit Shinto shrines for the birth of a child, attend church-style wedding ceremonies, and hold funerals at Buddhist temples. The polytheistic Japanese culture is broadminded and peaceful in contrast to the monotheistic Western culture.

A Japanese institution attended this EORTC SWB project from Phase 3B (Vivat et al., 2013). All 15 Japanese participants responded with either “not at all” (n = 4) or “a little” (n = 11) to items concerning God or a being greater than themselves. Furthermore, some Japanese participants had negative comments about these items, e.g., “I am tired of answering repeated religious questions.” Vivat, who was a principal investigator of the EORTC SWB project, reported that the most marked difference between nationalities was observed in European and Japanese participants’ responses to religious items(Vivat et al., 2013). The European participants’ responses to these items spanned the entire range of categories, with no notable differences between the nationalities (Vivat et al., 2013). Based on Japanese experience, the religious items were adapted accordingly; some were rephrased, and five items were combined to form two items. Furthermore, there were two so-called “skip” items regarding religious matters; in the case of responding with “not at all” to these items, the participant could avoid responding to additional religious items. Thus, the EORTC SWB questionnaire can discriminate between people with and without religious sense. After the end of Phase 3B pilot-testing, the 36-item version was developed and tested in Phase 4. Finally, a 32-item version, EORTC QLQ-SWB32, was obtained, and its reliability and validity were established (Vivat et al., 2017).

The procedures of QoL investigation might reveal critical relationships between the structures of spirituality and religious sense, especially in young people. Therefore, by using EORTC QLQ-SWB32, we performed a retrospective observational study, which investigated the spiritual well-being (SWB) of high-school students in Japan, where people live in a society without strong religious influences.

Methods

In March 2021, students of Saitama Prefectural Kumagaya High School answered the EORTC QLQ-SWB32 questionnaire in a classwork of Super Science High School (SSH) funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. EORTC QLQ-SWB32 first asks for the respondent’s initials and date of birth; however, this personal information was not required in the classwork. Ethical approval (#2021-060) for conducting this retrospective observational study was provided by the Institutional Review Board of Saitama Medical University International Medical Center in July 2021.

Questionnaire used

The participants completed the Japanese version of EORTC QLQ-SWB32, which was broadly followed by the EORTC translation procedure (Dewolf et al., 2009). Thirty-one items of EORTC QLQ-SWB32 employ a 4-point scale (not at all, a little, quite a bit, very much). The 31 items have five scales: Relationship with Others (RO) constructed by items 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13; Relationship with Self (RS) constructed by items 5, 6, 7, 17, 18, and 19; Existential (EX) constructed by items 1, 2, 3, 14, 15, and 16; Relationship with Someone or Something Greater (RSG) constructed by items 20, 21, 22, 23, 26, 27, 30, and 31; and Change (CH) items 24, 25, 28, and 29. Item 32 is a global item, for which the participants score their global SWB on a 7-point response scale of 1 (very poor) to 7 (excellent), the same as the global QOL items of EORTC QLQ-C30 (Aaronson et al., 1993), and an additional option of 0 for “don’t know/can’t answer.” The items of each scale are neutrally questioned except for those of the RS scale, which are negatively asked (Vivat et al., 2017).

EORTC QLQ-SWB32 has two “skip” items; item 22 (“I believe in God or in someone or something greater than myself”) and item 23 (“I have always believed in God or in someone or something greater than myself”) (Vivat et al., 2017). A respondent who responds to both items with “not at all” skips items 24, 25, and 26 and directly goes to items 27–32. Items 24, 25, and 26 are “My beliefs have changed since I have felt less well,” “My beliefs have changed in the last few weeks,” and “I feel connected to God or to someone or something greater.” These skip items were obtained through Japanese experiences in Phase 3B pilot-testing as described in the first section (Introduction) (Vivat et al., 2013).

The 4-point scale and the 7-point response scale were transformed to a 0–100 scale, and missing data were dealt with according to the EORTC QLG scoring manual (http://qol.eortc.org/manual/scoring-manual/). Each scale score of RO, RS, EX, RSG, and CH was calculated as a sum of item scores per item numbers, resulting in 0-100 scale. The response data of item 32 were analyzed separately.

Believers or non-believers

The “skip” screening instructions can distinguish “believers” from “non-believers.” The total score of items 22 and 23 is in the range of 0 to 200. A score of zero indicates non-believers who responded with “not at all” to both the screening items. A score of 33 or more indicates believers. Furthermore, believers are divided into two groups: light believers (a score of less than 100) and deep believers (a score of 100 or more). The distribution of non-believers, light believers, and deep believers among high-school students was estimated.

Spiritual structure

The validation report of EORTC QLQ-SWB32 stated that it had 5 scales as described above (Vivat et al., 2017). We assessed each reliability of RO, RS, EX, RSG, and CH using Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach & Warrington, 1951), with a threshold of 0.7 (Fayers & Machin, 2008).

We investigated the scale structure using principal component analysis (PCA) with Oblimin rotation to explore scale-grouping and identify suitable items to form scales. In the previous report, scree plots and eigenvalues greater than 1 were used to identify the optimum number of factors and 5 factors were extracted (Vivat et al., 2017). Thus, we employed the same 5 factors after these eigenvalues were confirmed to be greater than 1, with a threshold value of 0.4 for the item loading coefficients.

Global SWB

A structure analysis was conducted by calculating the correlation coefficient between the global SWB measured by item 32 and each scale-score of RO, RS, EX, RSG, and CH. The conceptually related scales were expected to correlate substantially with one another (r > 0.40) (Aaronson et al., 1993).

In terms of the global SWB of the high-school students, the difference in the item 32 scores among non-believers, light believers, and deep believers was investigated using one-way ANOVA.

Statistical analyses

Distribution of non-believers, light believers, and deep believers, and Cronbach’s alpha were calculated by using Microsoft® Excel® (version 2204). All other statistical analyses of PCA, correlation coefficients between the global SWB and each scale-score, and difference in global SWB using one-way ANOVA were performed using JMP® Pro 16.1.0.

Results

Participants

A consort diagram (Fig. 1) shows the participants in this study. A total of 285 students of Kumagaya High School returned the EORTC QLQ-SWB32 questionnaire. Except for 2 students who responded to no items at all, the data of the remaining 283 were analyzed in this study. As Kumagaya High School is a boys’ school, the 283 students, who lived in Saitama prefecture locating 70 km from Tokyo in Japan, were all healthy males, and their ages were in the range of 15 to 17 years.

Believers or non-believers

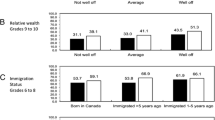

The distribution obtained by adding the scores of items 22 and 23 is shown in Fig. 2A. There were 142 (50%) non-believers who responded with “not at all” to both the screening items (score: 0). Further, it was found that 141 (50%) believers believed lightly or deeply in God or in someone or something greater than themselves. It was reasonable that the believers were divided into two groups, i.e., light believers and deep believers, because of the distribution shown in Fig. 2A, Cronbach’ alpha values listed below, and the item-response patterns themselves. Namely, students who responded with “a little” to items 22 and 23 of “I (have always) believe(d) in God or in someone or something greater than myself,” were light believers (score: 33–66). The rest who responded with “quite a bit” and/or “very much” were deep believers (score: 100–200). The numbers of light and deep believers were 98 (35%) and 43 (15%), respectively.

Non-believers, light believers, and deep believers.

(A) Score distribution of items 22 plus 23.

(B) Frequency of non-believers, light believers, and deep believers among high-school students

Non-believers, light believers, and deep believers are defined by 0, 33.3–66.6, and 100–200, respectively, on items 22 and 23, ranging from 0 to 200 points

Internal reliability

The Cronbach’s alpha values were calculated using 31 items for the believers and 28 items (except for items 24, 25, and 26) for the non-believers. The Cronbach’s alpha values for all 5 scales were above 0.7 for the believers (Table 1), indicating that the internal reliabilities were satisfied. Among the non-believers, although EX, RO, and RS had good reliability, RSG and CH did not. It was indicated that there might be a difference in the scale structure of spirituality between non-believers and believers. Furthermore, among the believers, there were differences in the results of internal reliability between deep believers and light believers (Table 1), suggesting different structures of spirituality between them. RSG did not show internal reliability in the case of light believers.

Spiritual structure

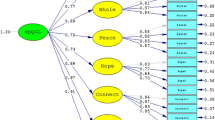

Thus, among deep believers, light believers, and non-believers, each structure of spirituality was investigated using PCA with Oblimin rotation as in the previous Phase 4 report (Vivat et al., 2017). The first factor was a combination of EX and RO among the three groups (Fig. 3; Table 2), indicating that EX and RO were critical to spirituality in all the students. As for the deep believers (Fig. 3 A, Table 2 A), the CH and RSG items made factors of 3 and 4, respectively. For the non-believers, the RSG items except for RSG item 31, “I have spiritual well-being,” did not make any factor (Table 2 C). As a factor of 1 indicates a strong relationship with spirituality because of its high eigenvalue, item 31 might function like item 32 in terms of the global SWB (Fig. 3 C). As for the light believers, the CH items with RSG item 26, “I feel connected to God or to someone or something greater than myself,” made a factor of 2 (Table 2B). However, the RSG items except for item 26 had no factor. These indicated that the spiritual structure of the light believers might be an intermediate one between that of the deep believers and non-believers.

Global SWB

To simplify these various relationships, a model explaining the relationships between the global SWB and RO, RS, EX, RSG, and CH was investigated (Table 3). For all the non-believers, light believers, and deep believers, EX modestly correlated with the global SWB. Further, RS modestly correlated with the global SWB for the non-believers and light believers. Meanwhile, RO modestly correlated with the global SWB for the deep believers. In terms of RSG, the correlation coefficients increased in the order of non-believers (r = 0.295), light believers (r = 0.399), and deep believers (r = 0.559), indicating modest correlations between the global SWB and RSG for the deep believers.

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, and 3, each of the non-believer, the light believer and the deep believer has different weights on EX, RO, RS, RSG, and CH. Therefore, comparison of each scale among 3 types of believers is difficult to understand. Only the global SWB, which is an equivalent value for all students, can be compared. Considering the non-believers, light believers, and deep believers among the high-school students in Japan, there was a significant difference in the score of item 32, “How would you rate your global spiritual well-being?” (ANOVA: p = 0.0312, Fig. 4). The light believers had the best status in terms of the global SWB. Contrary to expectations, the global SWB of the deep believers among high-school students was not very good

Discussion

We investigated the spirituality of high-school students by employing EORTC QLQ-SWB32, and it was found that the RSG affected their spiritual structures. Among high-school students in Japan, there are three types of spiritual structure: non-believers, light believers, and deep believers. The importance of RSG in spirituality increases in this order.

Japan is a unique society that is not strongly affected by religions as described in the introduction. A report employing 4 questions addressing the extent of participants’ religious, spiritual or personal belief besides the World Health Organization’s QOL Instrument (the WHOQOL) indicated that there were non-negligible numbers of non-believers and light believers in several countries; China:77.1%, Japan:74.3%, Israel:60.1%, Lithuania 52.5%, Urguay:49.8%, UK:47.8%, Spain:42.9%, and Italy:31.4% (WHOQOL SRPB Group., 2006). It is recently shown that Europeans generally are less religious than people in other parts of the world (Evans & Baronavski, 2018). A Canadian survey showed a declining share of Canadians identify as Christians (55%), while an increasing share say they have no religion (29%) (Lipka, 2019). With ongoing technological progress, the numbers of non-believers and light believers might increase even in religious countries.

Assessments asking spirituality/religiousness have been born in religious countries (Ferrell et al., 1995; Peterman et al., 2002; WHOQOL SRPB Group, 2006), and have focused on believers (Borges et al., 2021). In recent literatures searched on PubMed by keywords of “factor analysis or principal component analysis, spirituality/religion, and adolescent,” there are a few studies investigating relationship between spiritual structures of healthy people and religiousness (Tavel et al., 2022; Vitorino et al., 2018). Employing the Shortened Version of the Spiritual Well-Being Scale, Tavel P, et al. described religious respondents scored significantly higher on the two subscales of religious well-being and existential well-being (Tavel et al., 2022). Vitorino LM et al., reported that participants with high religiousness had better outcomes as compared to those with low religiousness in the WHOQOL Psychological and Social Relationship, and Optimism (Vitorino et al., 2018). However, there have been few reports focusing on spiritual structures of non-believers and light believers. The EORTC QLQ-SWB32 has both items asking whether having a religious sense or not and an item concerning the global SWB (Vivat et al., 2017), and is able to investigate spiritual structures for non-believers, light believers, and deep believers. Clarifying spiritual structures in people with or without religious sense has been a central topic especially in adolescents. To our knowledge, Table 2B and C employing PCA might be the first reported ones showing spiritual structures not affected by RSG in non-believers and light believers. Furthermore, Table 2 indicated importance of relationship with self and others on the global SWB when lacking for sense of RSG.

Comparing high-school students to lung-cancer patients (n = 59, median age:69 years), who enrolled in Phase 4 in 2012, and lived in the same region of Japan (Vivat et al., 2017), the incidence of non-believers among lung-cancer patients was lower than that among high-school students (Fig. 2, Suppl Fig. 1). Experience from aging itself might be considered as a reason. Furthermore, feeling that death is near might make people recognize RSG. Internal consistencies were proved for EX, RO, RS, and RSG but not for CH in patients with lung cancer (Suppl Table 1). Using lung-cancer patients (n = 59), PCA with Oblimin rotation showed that the RSG items made the second factor (Suppl Fig. 2, Suppl Table 2). Although a limited number (n = 49) tested owing to missing data for item 32, by having an additional option of 0 for “don’t know/can’t answer,” the global SWB correlated with RSG at more than 0.4 for deep believers among lung-cancer patients (Suppl Table 3). In terms of light believers, the correlation coefficients between the global SWB and RSG were 0.399 for high-school students and 0.388 for lung-cancer patients (Table 3, Suppl Table 3). Interestingly, RS corelated with the global SWB for light believers among high-school students (-0.48, Table 3), whereas RO corelated with the global SWB for lung-cancer patients (0.56, Suppl Table 3). Even in the same culture, there was a difference in the relationship with self/others between high-school students and lung-cancer patients. Aging and life experience might be a reason for this change from RS to RO.

The following is a hypothesis; the most important issue to a human being is EX related to death, and to overcome no EX, a human being must have good RO and/or good RS. Believing in RSG becomes important only to believers. In the case of non-believers, relationship with self/others becomes critical instead of RSG. One can be a non-believer, light believer, or deep believer based on one’s own decision in a culture without any religious coercion. A priest sometimes visits a patient who has a religion in a palliative care unit. While there are patients who love friends and families and eager to meet them. Not only in palliative care but also in high school life, practitioners or instructors should pay attention to person’s structure of spirituality. Here, we wish to emphasize that a human being with any deepness of RSG is equally respected.

For non-believers, light believers, and deep believers among patients with lung cancer in Japan, there was a significant difference in the global SWB score (ANOVA: p = 0.0085, Suppl Fig. 2). Deep believers had the best global SWB among the groups with lung cancer. This result is identical with many studies previously reported (Borges et al., 2021; Ferrell et al., 1995; Vitorino et al., 2018). For example, the spiritual module of Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-Sp) was related to the overall global QoL (Ferrell et al., 1995). Contrary to expectations, the deep believers among high-school students did not have the best global SWB (Fig. 4). Similar phenomenon was recognized by Zidkova et al. They investigated relationships among spirituality, religious attendance, and health complaints of adolescents in a secular country, and found that religious well-being was associated with a higher risk of nervousness (Zidkova et al., 2020).

This study has some limitations. As Kumagaya High School is a boys’ high school, the participants of this study were only males. A Canadian national, cross-sectional study using Fisher’s spiritual well-being scale indicated that girls on average reported spiritual health as being more important than did boys (Michaelson et al., 2016). It is necessary to investigate girls’ spiritualities in Japan. Moreover, Japan has unique circumstances with regard to religious matters. A study investigating QoL and religiosity among Muslim college students reported that religiosity was the second factor (Abdel-Khalek, 2010). The spirituality of people who live in other countries with strong religious influences should be investigated via a QoL assessment such as the EORTC QLQ-SWB32.

In conclusion, the deepness of believing in RSG clearly affects spirituality, and the structures of spirituality differ among deep believers, light believers, and non-believers.

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

28 November 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04026-6

References

Aaronson, N. K., Ahmedzai, S., Bergman, B., Bullinger, M., Cull, A., Duez, N. J., Filiberti, A., Flechtner, H., Fleishman, S. B., & Haes, J. C. (1993). The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85(5):365 – 76. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. PMID: 8433390.

Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2010). Quality of life, subjective well-being, and religiosity in Muslim college students. Quality of Life Research, 19(8), 1133–1143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9676-7. Epub 2010 Jun 29. PMID: 20585988.

Ahlner-Elmqvist, M., & Kaasa, S. (1998). The construction of a palliative care module – social support and spirituality – preliminary report on phases IA, IB, IC, II and III, for EORTC Study Group on Quality of Life. Internal EORTC QLG document.

Balboni, T. A., VanderWeele, T. J., Doan-Soares, S. D., Long, K. N. G., Ferrell, B. R., Fitchett, G., Koenig, H. G., Bain, P. A., Puchalski, C., Steinhauser, K. E., Sulmasy, D. P., & Koh, H. K. (2022). Spirituality in Serious Illness and Health. JAMA. 328(2):184–197. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.11086. PMID: 35819420.

Best, M., Butow, P., & Olver, I. (2015). Do patients want doctors to talk about spirituality? A systematic literature review. Patient Education and Counselling, 98, 1320–1328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.04.017. Epub 2015 May 19. PMID: 26032908.

Borges, C. C., Dos Santos, P. R., Alves, P. M., Borges, R. C. M., Lucchetti, G., Barbosa, M. A., Porto, C. C., & Fernandes, M. R. (2021). Association between spirituality/religiousness and quality of life among healthy adults: a systematic review. Health And Quality Of Life Outcomes, 19(1), 246. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01878-7

Cronbach, L. J., & Warrington, W. G. (1951). Time-limit tests: estimating their reliability and degree of speeding. Psychometrika, 16(2):167 – 88. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289113. PMID: 14844557.

Dewolf, L., Koller, M., Velikova, G., Scott, N., & Bottomley, A. (2009). EORTC Quality of Life Group Translation Procedure, 3rd ed. EORTC Quality of Life Group. http://qol.eortc.org/manuals/

Evans, J., & Baronavski, C. (2018). How do European countries differ in religious commitment? Use our interactive map to find out. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/12/05/how-do-european-countries-differ-in-religious-commitment/

Fayers, P. M., & Machin, D. (2008). Quality of Life, the Assessment, Analysis and Interpretation of Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2nd Edition, Wiley, Chichester. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.01082_11.x

Ferrell, B. R., Dow, K. H., & Grant, M. (1995). Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Quality of Life Research. 4(6):523 – 31. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00634747. PMID: 8556012.

Johnson, C., Aaronson, N., Blazeby, J. M., Bottomley, A., Fayers, P., Koller, M., Kuliś, D., Ramage, J., Sprangers, M., Velikova, G., & Young, T. (2011). EORTC Quality of Life Group. Guidelines for developing questionnaire modules (4th ed.). Brussels: EORTC. https://qol.eortc.org/manuals/

Kyranou, M., & Nicolaou, M. (2021). Associations between the spiritual well-being (EORTC QLQ-SWB32) and quality of life (EORTC QLQ-C30) of patients receiving palliative care for cancer in Cyprus. BMC Palliative Care, 20(1), 133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00830-2. PMID: 34461881; PMCID: PMC8404401.

Lipka, M. (2019). 5 facts about religion in Canada. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/07/01/5-facts-about-religion-in-canada/

Michaelson, V., Freeman, J., King, N., Ascough, H., Davison, C., Trothen, T., Phillips, S., & Pickett, W. (2016). Inequalities in the spiritual health of young Canadians: a national, cross-sectional study. Bmc Public Health, 16(1), 1200. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3834-y. PMID: 27894342; PMCID: PMC5126831.

Tavel, P., Jozefiakova, B., Telicak, P., Furstova, J., Puza, M., & Kascakova, N. (2022). Psychometric Analysis of the Shortened Version of the Spiritual Well-Being Scale on the Slovak Population (SWBS-Sk). International Journal of Environmental Research And Public Health, 19(1), 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010511. PMID: 35010770; PMCID: PMC8744853.

Peterman, A. H., Fitchett, G., Brady, M. J., Hernandez, L., & Cella, D. (2002). Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy–Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 24(1):49–58. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. PMID: 12008794.

Phelps, A. C., Lauderdale, K. E., Alcorn, S., Dillinger, J., Balboni, M. T., Van Wert, M., Vanderweele, T. J., & Balboni, T. A. (2012). Addressing spirituality within the care of patients at the end of life: perspectives of patients with advanced cancer, oncologists, and oncology nurses. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30, 2538–2544. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3766. Epub 2012 May 21. PMID: 22614979; PMCID: PMC4827261.

Rohde, G. E., Young, T., Winstanley, J., Arraras, J. I., Black, K., Boyle, F., Bredart, A., Costantini, A., Guo, J., Irarrazaval, M. E., Kobayashi, K., Kruizinga, R., Navarro, M., Omidvari, S., Serpentini, S., Spry, N., van Laarhoven, H., Yang, G., & Vivat, B. (2019). Associations between sex, age and spiritual well-being scores on the EORTC QLQ-SWB32 for patients receiving palliative care for cancer: A further analysis of data from an international validation study. European Journal of Cancer Care, 28(6), e13145. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13145. Epub 2019 Aug 21. PMID: 31433533.

Vitorino, L. M., Lucchetti, G., Leão, F. C., Vallada, H., & Peres, M. F. P. (2018). The association between spirituality and religiousness and mental health. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 17233. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35380-w. PMID: 30467362; PMCID: PMC6250706.

Vivat, B. (2008). Spiritual issues for palliative care patients: a literature review. Palliative Medicine, 22, 859–868. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216308095990. Epub 2008 Aug 28. PMID: 18755826.

Vivat, B., Young, T., Efficace, F., Sigurđadóttir, V., Arraras, J. I., Åsgeirsdóttir, G. H., Brédart, A., Costantini, A., Kobayashi, K., Singer, S., & EORTC Quality of Life Group. (2013). Cross-cultural development of the EORTC QLQ-SWB36: A stand-alone measure of spiritual wellbeing for palliative care patients with cancer. Palliative Medicine, 27, 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216312451950. Epub 2012 Jul 27. PMID: 22843128.

Vivat, B., Young, T. E., Winstanley, J., Arraras, J. I., Black, K., Boyle, F., Bredart, A., Costantini, A., Guo, J., Irarrazaval, M. E., Kobayashi, K., Kruizinga, R., Navarro, M., Omidvari, S., Rohde, G. E., Serpentini, S., Spry, N., Van Laarhoven, H. W. M., Yang, G. M., & EORTC Quality of Life Group. (2017). The international phase 4 validation study of the EORTC QLQ-SWB32: A stand-alone measure of spiritual well-being for people receiving palliative care for cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 26(6), https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12697. Epub 2017 Aug 4. PMID: 28776784.

WHOQOL SRPB Group. (2006). A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life. Social Science & Medicine, 62(6), 1486–1497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.001. Epub 2005 Sep 13. PMID: 16168541.

Yonker, J. E., Schnabelrauch, C. A., & Dehaan, L. G. (2012). The relationship between spirituality and religiosity on psychological outcomes in adolescents and emerging adults: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescence, 35(2), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.08.010. Epub 2011 Sep 14. PMID: 21920596.

Zidkova, R., Glogar, P., Polackova Solcova, I., van Dijk, P., Kalman, J., Tavel, M., & Malinakova, P. K (2020). Spirituality, Religious Attendance and Health Complaints in Czech Adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 30(7), 2339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072339. PMID: 32235661; PMCID: PMC7177996.

Acknowledgements

Students and patients who answered EORTC QLQ-SWB32 are acknowledged. We also thank the head teacher, Mr. Noriyuki Kameyama, and an instructor, Mr. Masahiro Morinaga, of Saitama Prefectural Kumagaya High School for giving us the opportunity to conduct the study.

Funding

This study was supported by a non-profit organization (NPO) the North East Japan Study Group, and Project of Super Science High School (SSH), funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: KO and KK; Methodology: KK; Formal analysis and investigation: KO, TG, Ski, Ska, SM and KK; Writing - original draft preparation: KK; Writing - review and editing: KO, TG, Ski, Ska, SM and KK; Supervision: SM.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Author KO, TG, Ski, SKa and SM declare they have no financial interests. KK has received speaker honorarium from AstraZeneca and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company.

Ethics approval

his retrospective study was in accordance with the institutional research committee, Japanese ethical standards of Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Biological Research Involving Human Subjects, and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Saitama Medical University International Medical Center approved this study (#2021-060).

Informed consent

Written informed consent was not applicable for this retrospective study, which used data from completed questionnaires without personal information. According to IRB’s instruction, a public announcement of this study was done on a website to get participated students’ opinions.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article has been revised. Table 2 footnote has been correctly captured.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohata, K., Gonokami, T., Kinjo, S. et al. Structure of spirituality among high-school students differs depending on relationship with someone or something Greater (RSG). Curr Psychol 42, 26709–26719 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03694-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03694-8