Abstract

The relationship between suicidality, depression, anxiety, and well-being was explored in young adults (median age 20.7 years) from the State of Yucatan (Mexico), which has a suicide rate double that of other Mexican states. A cross-sectional study was carried out in 20 universities in Yucatan and 9,366 students were surveyed using validated questionnaires built into a smartphone app, applying partial least squares structural equation models. High suicide risk was assessed in 10.8% of the sample. Clinically relevant depression and anxiety levels were found in 6.6% and 10.5% of the sample, respectively, and 67.8% reported high well-being. Comparably higher levels of suicide risk, depression and anxiety, and lower well-being were found in women, who were also somewhat older than men in our study. Furthermore, path analysis in the structural equation model revealed that depression was the main predictor of suicidal behaviour as well as of higher anxiety levels and lower self-perceived well-being in the total sample and in both genders. Our findings draw attention to the association between suicidality, depression, anxiety, and well-being in Yucatan young adults and gender differences with this regard. Mental health screening via smartphone might be a useful tool to reach large populations and contribute to mental health policies, including regional suicide prevention efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the State of Yucatan, Mexico, the current suicide rate doubles the Mexican national average (Reyes-Foster, 2013), and this figure is rising (Cervantes & Montaño, 2020; Velázquez-Vázquez et al., 2019). Also, the local suicide mortality is quadruple that of homicide (González González Durán, 2021). An epidemiological study of suicides in Yucatan 2013–2016 from Velázquez-Vázquez and colleagues (2019) revealed that 60% of suicides were committed in rural or semi-urban areas, 43% completed secondary education, a third were married, and 71% belonged to the indigenous population. In this context, a comparative study of the living conditions and health in indigenous zones of the State of Yucatan between 1990 and 2005 (González, 2010) revealed a higher degree of marginalization and precarious health (i.e., higher degree of infant mortality) due to socio-economic inequalities. Furthermore, general prevention approach does not appear well-suited to the beliefs of the local indigenous communities (e.g., body-spirit balance vs. a biomedical model) (Reyes-Foster, 2013; González González Durán, 2021). Previous studies of suicidal behaviour in the State of Yucatan focused mostly on various psychosocial factors, and explored individual and contextual etiology of suicidality, indicating the lack of psychoeducation related to sadness, hopelessness (often connected to poverty), addiction, and societal violence (Belfer & Rohde, 2005; Reyes-Foster, 2013; Velázquez-Vázquez et al., 2019; González González Durán, 2021). Therefore, research on the role of the specific psychological/psychiatric risk factors (e.g., depression) in suicidal behaviour is needed.

As for Mexico as whole, Cervantes and Montaño (2020) investigated the burden of suicide mortality at the national and state level between 1990 and 2017 whereas an increase of the suicide rate nationwide, mainly in young males and females, was found. Of note, the Mexican states located in the southeast of the country - Tabasco, Campeche, Quintana Roo, and Yucatan - had the highest mortality rates and years of life lost for both genders, and an association with psychosocial factors has been suggested (Cervantes & Montaño, 2020; Garbus et al., 2022).

In terms of the distress (i.e., depression and anxiety) related to suicidality, whereas the role of depression as a major suicide risk factor is well established (i.e., about 80% of people who die by suicide meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder at the moment of death; Bertolote et al., 2004; Kato, 2014), the role of anxiety remains somewhat controversial. A meta-analysis found that anxiety is related to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, but not deaths by suicide (Bentley et al., 2016); however, there is also substantial evidence of an independent role of anxiety in in suicidal behaviour, both per se and as a comorbid symptom (Bolton et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2011; Sareen et al., 2005). In this context, previous studies highlighted the difficulty in isolating the effect of anxiety on suicide from that of depression (Zhang et al., 2019). Depression and anxiety are major contributors to the burden of years lived with disability, and suicide attempts account for a global annual loss of 20 million disability-adjusted life years (James et al., 2018).

In recent years, well-being has increasingly been used as an important outcome measure in the international context (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2020), and the World Health Organization (WHO) included well-being as a major objective in its health policy (“Health 2020”; WHO, 2013). According to the two-continua model of mental health and illness (Keyes, 2013), well-being is a dynamic construct theorized as two continuums: one indicates the presence or absence of mental health, and the other similarly indicates mental illness; in the latter one, it is understood that promoting and protecting mental health reduces the incidence and prevalence of mental illness. The interactions between well-being, depression, anxiety, and suicidal behaviour are of special interest in youths, as their measurements of well-being have been found to be inversely related with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation (Cederbaum et al., 2014; OECD, 2017; Sigfusdottir et al., 2016). Of interest, in international comparison, Mexican adolescents have highest levels of life satisfaction (OECD, 2020; Martinez-Nicolas et al., 2022). Studing the relationship among well-being, distress (depression and anxiety), and suicidality in community samples, particularly in areas with high sucide rates such as the State of Yucatan, might add to the existing knowledge on this phenomenon.

Finally, the mental health of university students and its promotion is an important topic in Latin America and worldwide (Belfer & Rohde, 2005; Hernández-Torrano et al., 2020). Numerous studies revealed higher prevalence of mental health problems in university students than in general population due to various factors such as full-time status (academic load), financial stress, social isolation, stigma of mental illness, etc. (Stallman, 2010; Storrie et al., 2010). We are not aware of previous studies on suicidal behaviour and associated factors among university students in Yucatan.

The aim of this study is to explore whether suicidality, depression, anxiety, and well-being are interrelated in young adults from the State of Yucatan, and in particular to determine whether depression, anxiety and well-being are associated with suicidality among young people in this area.

Methods

Study design

This population-based cross-sectional survey study follows the STROBE guidelines for reporting (von Elm et al., 2007). It is part of an over-arching research project in which ecological community mental health screening is performed by means of smartphone applications (apps) (Arenas-Castañeda et al., 2020).

Setting

The study sites were 20 higher education institutions (HEIs) in the State of Yucatan (Mexico): two public universities, 16 private universities, and two teacher-training colleges. All participating institutions provide educational opportunities across a wide range of degrees and disciplines for students older than 18 years of age.

The TEDUCA survey protocol is a massive suicide risk and social behaviour assessment in 24 pre-graduate education centres in Mexico City (30,000 users from 15 to 22 years old), considering other outcomes such as distress and addictions. Therefore, MeMind has been validated for use in Mexican population. For this, an app for Smartphone (MeMind system) or a web platform (www.MeMind.net) is used in which the participants take a self-administered questionnaire, composed of several psychometric instruments to identify the suicide risk. Thus, in the present study it had an open-ended recruitment period throughout the 2019–2020 academic year. Official recruitment started in late August 2019; students were invited via an institutional call to complete an online survey through the MeMind smartphone app (Barrigón & Cegla-Schvartzman, 2020). Participation was promoted by local HEIs, which encouraged involvement by holding talks at the beginning of the academic year, and the app was programmed to send anonymous reports to participants who wished it as an interactive app.

Study population and sampling design

The study population comprises 9,366 university students, all of whom agreed to participate in the survey from October to December 2019; 5,135 (54.8%) were women and 4,231 were men. In an effort to recruit as many students as possible, no sampling procedure was established beforehand.

Our inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age 18 years or above with enrolment at a participating institution; (2) ability to use either their own smartphone or an institutionally provided computer; (3) ability to understand the nature, purpose, and methodology of the study; (4) participation in accordance with express informed consent granted in the app. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) individuals deprived of liberty (by judicial or administrative decision); and (2) students protected by law (guardianship or conservatorship).

Variables

Outcomes

Our main outcome variables were the following: (A) suicidal behaviour; (B) depression; (C) anxiety; and (D) subjective well-being. Each of these were latent variables measured with a specific instrument (see Table 1). Individual items on each questionnaire were considered observed variables of the latent construct. Of note, our analyses were stratified by gender, given the role of gender on the clinical presentation of most mental health outcomes, including suicidality (Barrigón & Cegla-Schvartzman, 2020), depression (Ogrodniczuk & Oliffe, 2011; Oliffe & Phillips, 2008), and anxiety (McLean et al., 2011).

Data sources and measurement

Smartphone app

Assessments were conducted using the MeMind app, a smartphone/web-based platform extensively described elsewhere (Arenas-Castañeda et al., 2020; Barrigón, Berrouiguet et al., 2017; Berrouiguet et al., 2015, 2017; Jung et al., 2019; Lopez-Castroman et al., 2015), which features a SMART-SCREEN protocol. This protocol is an innovative tool for mental health screening that has been designed to explore and understand the distribution of suicidal behaviours in the general population (Arenas-Castañeda et al., 2020). It detects and refer people at risk to current mental health facilities in the State of Yucatan, as it provides feedback about the assessment to improve help-seeking behaviour. Of note, as MeMind databases do not contain personal identification data on any individual, all data were collected anonymously using encrypted security protocols. The process of validating the MeMind app with its measures was first doing a short pilot testing in a smaller sample of voluntary Mexican adults in the City of Mexico before collecting data in the HEIs within the State of Yucatan.

Variables

To measure mental health outcomes including suicidal ideation, anxiety, depression, and well-being, we used several self-administered screening questionnaires that have been previously adapted to Spanish and used in Mexico (Arrieta et al., 2017; Barrigón, Rico-Romano et al., 2017). These instruments were included as built-in questionnaires of the MeMind app, listed as follows in the SMART-SCREEN protocol (Berrouiguet et al., 2019): (a) Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) screener version (Posner et al., 2011) to identify suicidal behaviour (Mundt et al., 2013); (b) the abbreviated version of Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al., 2006), which uses only two questions from the latter, i.e. GAD-2 (Hughes et al., 2018; Plummer et al., 2016) as an anxiety-screening instrument; (c) the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) depression screening (Kroenke et al., 2001); and (d) the World Health Organization Well-being Index (WHO-5) as a measure of well-being (Topp et al., 2015) based on an hedonistic theoretical foundation (Kusier & Folker, 2020) and with convergent validation with the flourishing construct (Pacak-Vedel et al., 2021). Thus, it was used in the inverse order (i.e., WHO-5, PHQ-9, and C-SSRS). For details regarding the short scales selected, please, see Table 1 for the items included in the protocol (i.e., SMART-SCREEN), or the previous study in which the MeMind app was used to screen for suicidal behavior and other correlated factors in a Mexican rural community (Arenas-Castañeda et al., 2020).

For all questionnaires, we used previously described specific cut-off points. Regarding the C-SSRS scale, suicide risk was classified as low, moderate, or high (Posner et al., 2011). For PHQ-9, total scores below 4 were considered as “no need for treatment”, scores between 4 and 14 as “need to screen for depression”, and scores above 14 as “need for treatment for depression” (Arrieta et al., 2017). For GAD-2, a cut-off point of 3 was set to consider the presence of an anxiety disorder (Plummer et al., 2016). For WHO-5, we used a cut-off point of 50, with higher scores associated with a greater sensation of well-being, following previous work (Topp et al., 2015). Further detail of the aforementioned questionnaires is described elsewhere (Arenas-Castañeda et al., 2020).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analysis

Descriptive and exploratory analyses were performed in order to describe participant characteristics, including subgroup analyses by gender, using t-tests or non-parametric alternatives as appropriate.

SEM modelling

Partial least squares structural equation models (PLS-SEM) were used to establish statistical casual relationships between the four latent variables (i.e., suicidality, depression, anxiety and well-being) in the overall study population (herein, Main model), as well as after stratification by gender. Values for observed variables, path coefficients, and their respective non-parametric hypothesis tests were reported. Two indices (and their respective cut-offs) were used to evaluate model fit in both main and subgroup data analyses: the Standardized Root Mean-squared Residual (SRMR; < 0.08), and the Normed Fit Index (NFI; > 0.9) (Bentler, 1990; Mos, 2009). We used a threshold of p < 0.05 for statistical significance.

Ethical issues

Ethical approval (001/2019) was obtained from the Ethics Review Board of the ‘Hospital Psiquiátrico Yucatán’, Merida, State of Yucatan (Mexico).

Results

Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 2. Of a total 9,366 participants with a median age of 20 years and 8 months, 55% were females. When compared to males, females were on average 6 months older and had higher levels of suicide risk, anxiety, and depression as well as lower levels of self-perceived well-being.

SEM models

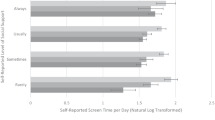

Figure 1 describes the general structure for our SEM model, which was constructed for both the whole study population and by sex. Table 3 represents the goodness of fit of the models in terms of SRMR and NFI. All observed variables (questionnaire items) were statistically significant with the exception of (i) question 1 of PHQ-9 (“little interest or pleasure in doing things”) in gender-specific models (0.45, p = 0.09, in males; and 0.14, p = 0.41, in females); and (ii) question 2 of GAD-2 (“feeling afraid as if something awful might happen”) across all models. Results of individual item coefficients for each model are available in Appendix 1 (Online Resource 1).

Results from SEM models (Table 4) show that depression was associated with anxiety, suicidal behaviour, and well-being in the whole population and after stratifying by gender. Furthermore, anxiety and well-being were associated in men but not women; this indicates that depression was the main predictor with a path to well-being in the whole study population, competing with anxiety only among men.

Final statistically significant paths of SEM models are shown in Fig. 2 for the study population and in Fig. 3 for men and women separately.

Discussion

The findings of our study applying a PLS-SEM analysis show that depression was the main predictor of suicidal behaviour within our network of 4 psychological factors in a large sample of young adults from the State of Yucatan. Furthermore, depression was significantly associated with higher suicidality, higher anxiety, and decreased well-being in young men and women in this population. We recently published a paper on using this new methodology - PLS-SEM analysis - in a work/in/progress clinical trial of the MeMind app in Mexico City (Martinez-Nicolas et al., 2022). Other similar studies usually applied the mediation model using SEM, multiple or logistic regression analyses, and analysis of variance (e.g., Kato 2014, Nadorff et al., 2011).

In our sample, 6.6% of Yucatan young adults had clinically relevant depression level (female > male), 10.5% clinically relevant anxiety levels (women slightly more than men), and 10.8% had high risk of suicide (women slightly more than men). A recent North American study of a student at-risk population has shown higher rates of depression and suicidal tendencies (26.3% and 19.7% respectively; Lustig et al., 2022) than in our study. Young women in our study had higher suicide risk than men, although the completed suicides in the State of Yucatan occur predominantly in men (Cervantes & Montaño, 2020).

However, we did not find significant path between anxiety and suicidal behaviour, whereas the reduced sensitivity of the anxiety measure used our study (GAD-2) might have played a role. Depression was the main predictor of both conditions, anxiety and suicidality, in our study. Previous research pointed out that depression-anxiety comorbidity is a more important risk factor for suicidality than these conditions alone or other diagnoses (Baca García & Aroca, 2014; Chesney et al., 2014). Furthermore, there were gender differences regarding the association between anxiety and well-being in our study. Higher anxiety levels were related to increased well-being in men, but not women. This counterintuitive finding might reflect the heterogeneity of anxiety as a phenomenon and can also result from a lack of goodness-of-fit, a suppressing effect of depression on anxiety, or inconsistent mediation (Rucker et al., 2011); this needs further study. Since previous research does not offer a plausible explanation for our paradoxical findings in men, other factors like academic stress, substance use, high-risk sports/hobbies and certain contextual factors not assessed in this study could also have influenced this finding. On the other hand, our results support the notion that the effect of depression on well-being may be partially mediated by anxiety (Martinez-Nicolas et al., 2022). Other studies have shown the complex relationship between anxiety and depression and its impact on suicidality (Cunningham et al., 2008; Iliceto et al., 2011; Thompson et al., 2005). In this context, current evidence has shown that irritability and temper could be key components of the anxiety-depression complex (Cunningham et al., 2008; Iliceto et al., 2011), e.g. “male depression” as the clinical phenotype characterized by irritability, anger, aggression, substance misuse, low impulse control, risk-taking, or impulsivity (Ogrodniczuk & Oliffe, 2011; Oliffe & Phillips, 2008). However, neither study carried out structural equation modelling to determine directionality or allow confirmation of the gender-based differences detected.

There was no significant relationship between suicidality and well-being in our study of Yucatan young adults, however well-being was inversely associated with the main predictor of suicidal behaviour, depression. Previous research reported an inverse association between suicide rates and proxies of well-being, such as happiness and life satisfaction (Bray & Gunnell, 2006) in unselected cohorts of adults and college students (Koivumaa-Honkanen et al., 2004; Ridner et al., 2015; Wood & Joseph, 2010), which is consistent with the two-continua model of Keyes (2013). Our finding is also in contrast with previous reports about an inverse relationship between suicidal behavior and well-being among adolescents (Cederbaum et al., 2014; Sigfusdottir et al., 2016), and this deserves further studies. Of note, two-third of Yucatan young adults in our study reported high well-being (male > female). In this context, a recent review revealed that suicide ideation emerged in individuals who self-reported full mental health, which indicates that mental illness and positive (subjectively perceived) mental health reflect distinct continua rather than the extreme ends of a single spectrum (Iasiello et al., 2020). Previous research also points out that young adults without diagnosed mental illness (i.e., being free from disease and distress) have sometimes impaired functioning (e.g. physical condition, healthcare utilization, work or academic productivity), including psychosocial functioning (Westerhof & Keyes, 2010).

Next, other factors that have not been explored in this study may interact in the connection between depression, anxiety, and well-being influencing their association with suicidal behaviour of young adults. In a study of Asian adolescents in average 19 years old on predictors of lethality of suicide attempts, only resolution of precipitants of suicide attempt yielded a statistically significant contribution (Choo et al., 2017). Furthermore, other risk (e.g., personality, emotional distress, relationship issues, problematic substance use, a history of trauma or abuse, chronic pain) and protective (e.g. strong personal relationships, religious or spiritual beliefs, lifestyle practice of positive coping strategies) factors could also play a role with this regard (Choo et al., 2017; WHO, 2014). Some of these factors, such as traumatic life-events and self-esteem, and their association with suicidality were also reported in recent Mexican studies with adolescents (Borges et al., 2021; Garbus et al., 2022). As our study population were young adults, the effect of existing comorbidities on suicidality may not exert the same influence as in adolescent or older populations, and risk factors such as alcohol and drug consumption, and online addiction (Kuss et al., 2021) could be of utmost importance in this interaction (Lenz et al., 2019; Swendsen, 2000).

Given the status of depression as the main predictor of suicidal behaviour, mental health action in the State of Yucatan aiming early detection and treatment of depression in HEIs could contribute to prevention of suicidal behaviour. In this context, the presence of stigma towards mental health problems among university students in Yucatan was reported, and this needs to be addressed (Storrie et al., 2010). A universal school-based screening successfully increased identification individuals with symptoms of major depressive disorder and treatment initiation among the U.S. adolescents (Sekhar et al., 2021). Notably, the present study through MeMindallows de-anonymization if the user gives authorisation. In this case, evaluations were sent to these students with those at very high risk of suicide being asked to contact mental health services in the State of Yucatan, and 65 previously untreated individuals from our study with a very high risk for started psychological/psychiatric treatment. However, it should always be considered that suicidal behaviour is the result of an interplay of multiple factors (i.e., sociodemographic, biological, psychiatric, psychosocial, in addition to the impact of stressful life events; Fazel & Runeson, 2020). Moreover, regionally and culturally-specific research on possible protective factors against suicidal behaviour should be encouraged.

The use of structural equations enabled us to identify relationships and even formulate hypotheses concerning the directionality of the possible causal relationships between depression, anxiety, well-being, and suicidal behaviour. The PLS-SEM presented here consists of exploratory models aimed at depicting the overarching causal structure underlying these latent variables. These preliminary models will serve to construct and, ultimately, refine a proper prediction model for screening purposes. PLS-SEM holds great potential in this concern over traditional covariance-based SEM (Hair et al., 2016). Moreover, our data were assessed through validated built-in questionnaires on a smartphone app designed to evaluate mental health in both clinical and community settings (Berrouiguet et al., 2015; McLean et al., 2011). In short, the MeMind mobile app was accessible and efficient as a screening system. It is well-accepted by young people and allows rapid screening of depression, anxiety, well-being, and suicide risk. In addition, other relevant risk assessment methods have emerged this last decade to prevent suicide in youth, such as the Suicidal Affect-Behaviour-Cognition Scale (SABCS; Harris et al., 2015), to tackle life/death ambivalence that can let to improve the multidimensionality of the suicidality construct.

A potential limitation of this study could be the use of a non-probabilistic sampling. This was intended to obtain responses that resemble those obtained had a community risk assessment been carried out. Attrition is a concern when using non-probabilistic sampling, as information from those who did not complete the questionnaires is a limitation of the study. In addition, those students without a smartphone may have been excluded, although local reports from the study setting indicate that most owned a smartphone. Another limitation is the fact the universities surveyed were private HEIs; however, in Mexico the 72% of HEIs are private, and the State of Yucatan had one of the higher education attainment rate between 2000 and 2015 (OECD, 2019), and this number has dramatically increased.

To offset this potential problem, the MeMind app was also available online (https://frontend.memind.net) and students were instructed on how to use it on a computer. Another limitation is the low goodness-of-fit we observed as measured by model indices. However, a PLS-SEM should not be assessed as a covariance-based model, and the goodness-of-fit indices that apply for PLS-SEM are in their early stages of development. It is known that a cut-off point of 0.08 is generally considered a good fit in CB-SEM, though this is likely too low for PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2016). As PLS-SEM is primarily intended for prediction rather than explanatory models, this lack of fit could be relaxed by prioritizing its predictive power. Another methodological limitation is not being able to identify a path between anxiety and suicidal behaviour, which could be a function of the reduced sensitivity of the anxiety measure used in the present study (it maybe more useful to have used GAD-7) or, alternatively, it may reflect the heterogeneity of anxiety as a phenomenon. Also, we were not able to identify a path between well-being and anxiety. Next, question 1 of PHQ-9 and question 2 of GAD-2 did not correlate with their corresponding constructs. Finally, the results of this study must be interpreted with caution when predicting mental health outcomes.

Conclusion

This study carried out in a large sample of young adults from the State of Yucatan, Mexico, using PLS-SEM analysis, shows that depression was the most important factor influencing their suicidal behaviour, anxiety level, and well-being in both genders. Therefore, early detection and treatment of depression among young people as a major suicide risk factor deserves particular attention; furthermore, the influence of depression on increased anxiety level and lower well-being needs consideration in planning comprehensive interventions. As young women had a higher suicide risk than men in our study, further studies on gender-specific risk and protective factors for suicidal behaviour are needed. The smartphone app used in this study may provide additional accessibility, usability, and efficiency for community screening and inform (regional) public policy decision-making. However, further research is needed in order to assess whether the models presented here can be used for prediction purposes.

Data Availability

Data and additional materials are available upon request.

Code Availability

The smartphone app used in this study is available through the Android app market and online at: https://frontend.memind.net.

References

Arenas-Castañeda, P. E., Bisquert, A., Martinez-Nicolas, F., Castillo Espíndola, I., Barahona, L. A., Maya-Hernández, I., Lavana Hernández, C., Manrique, M. M., Mirón, P. C., Barrera, A., Treviño, D. G., Aguilar, E., Barrios Núñez, A., De Jesus Carlos, G., Vildosola Garcés, A., Flores Mercado, J., Barrigon, M. L., Artes, A., De Leon, S., Molina-Pizarro, C. A., Franco, R., & Baca-Garcia, A., E (2020). Universal mental health screening with a focus on suicidal behaviour using smartphones in a Mexican rural community: Protocol for the SMART-SCREEN population-based survey. British Medical Journal Open, 10(7), e035041. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035041

Arrieta, J., Aguerrebere, M., Raviola, G., Flores, H., Elliott, P., Espinosa, A., Reyes, A., Ortiz-Panozo, E., Rodriguez-Gutierrez, E. G., Mukherjee, J., Palazuelos, D., & Franke, M. F. (2017). Validity and utility of the patient health questionnaire (phq)-2 and PHQ-9 for screening and diagnosis of depression in rural Chiapas, Mexico: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(9), 1076–1090. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22390

Baca García, E., & Aroca, F. (2014). Factores de riesgo de la conducta suicida asociados a trastornos depresivos Y ansiedad. Salud Mental, 37(5), 373. https://doi.org/10.17711/sm.0185-3325.2014.044

Barrigón, M. L., & Cegla-Schvartzman, F. (2020). Sex, Gender, and Suicidal Behavior. In: Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 1–27.

Barrigón, M. L., Berrouiguet, S., Carballo, J. J., Bonal-Giménez, C., Fernández‐Navarro, P.,Pfang, B., Delgado-Gómez, D., Courtet, P., Aroca, F., Lopez-Castroman, J., Artés-Rodríguez, A., Baca-García, E., & MEmind study group. (2017). User profiles of an electronic mental health tool for ecological momentary assessment: MEmind. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 26(1), e1554. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1554.

Barrigón, M. L., Rico-Romano, A. M., Ruiz-Gomez, M., Delgado-Gomez, D., Barahona, I., Aroca, F., & MEmind Study Group. (2017). Comparative study of pencil-and-paper and electronic formats of GHQ-12, WHO-5 and PHQ-9 questionnaires. Revista de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental (English Edition), 10(3), 160–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2016.12.002

Belfer, M. L., & Rohde, L. A. (2005). Child and adolescent mental health in Latin America and the Caribbean: Problems, progress, and policy research. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 18(4–5), 359–365. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1020-49892005000900016

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Bentley, K. H., Franklin, J. C., Ribeiro, J. D., Kleiman, E. M., Fox, K. R., & Nock, M. K. (2016). Anxiety and its disorders as risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 43, 30–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.008

Berrouiguet, S., Courtet, P., Perez-Rodriguez, M., Oquendo, M., & Baca-Garcia, E. (2015). The Memind project: A new web-based mental health tracker designed for clinical management and research. European Psychiatry, 30, 974. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(15)31968-4

ygv, S., Barrigón, M. L., Brandt, S. A., Nitzburg, G. C., Ovejero, S., Alvarez-Garcia, R., Carballo, J., Walter, M., Billot, R., Lenca, P., Delgado-Gomez, D., Ropars, J., De la Calle Gonzalez, I., Courtet, P., & Baca-García, E. (2017). Ecological assessment of clinicians’ antipsychotic prescription habits in psychiatric inpatients: A novel web- and mobile phone–based prototype for a dynamic clinical decision support system. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(1), e25. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5954

Berrouiguet, S., Barrigón, M. L., Castroman, J. L., Courtet, P., Artés-Rodríguez, A., & Baca-García, E. (2019). Combining mobile-health (mHealth) and artificial intelligence (AI) methods to avoid suicide attempts: The Smartcrises study protocol. Bmc Psychiatry, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2260-y

Bertolote, J. M., Fleischmann, A., De Leo, D., & Wasserman, D. (2004). Psychiatric diagnoses and suicide: Revisiting the evidence. Crisis, 25(4), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.25.4.147

Bolton, J. M., Cox, B. J., Afifi, T. O., Enns, M. W., Bienvenu, O. J., & Sareen, J. (2008). Anxiety disorders and risk for suicide attempts: Findings from the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area follow-up study. Depression and Anxiety, 25(6), 477–481. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20314

Borges, G., Benjet, C., Orozco, R., Medina-Mora, M. E., Mendez, E., & Molnar, B. E. (2021). Traumatic life-events and suicidality among Mexican adolescents as they grow up: A longitudinal community survey. Journal of psychiatric research, 142, 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.08.001

Bray, I., & Gunnell, D. (2006). Suicide rates, life satisfaction and happiness as markers for population mental health. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(5), 333–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0049-z

Cederbaum, J. A., Gilreath, T. D., Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., Pineda, D., DePedro, K. T., Esqueda, M. C., & Atuel, H. (2014). Well-being and suicidal ideation of secondary school students from military families. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(6), 672–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.09.006

Cervantes, C., & Montaño, A. (2020). Study of suicide burden of mortality in México 1990–2017. Estudio de la carga de la mortalidad por suicidio en México 1990–2017. Revista brasileira de epidemiologia. Brazilian journal of epidemiology, 23, e200069. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-549720200069

Chesney, E., Goodwin, G. M., & Fazel, S. (2014). Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: A meta-review. World Psychiatry, 13(2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20128

Choi, H., Kim, S., Yun, K. W., Kim, Y. C., Lim, W., Kim, E., & Ryoo, J. (2011). A study on correlation between anxiety symptoms and suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Investigation, 8(4), 320. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2011.8.4.320

Choo, C. C., Harris, K. M., Chew, P., & Ho, R. C. (2017). What predicts medical lethality of suicide attempts in Asian youths? Asian journal of psychiatry, 29, 136–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2017.05.008

Cunningham, S., Gunn, T., Alladin, A., & Cawthorpe, D. (2008). Anxiety, depression and hopelessness in adolescents: a structural equation model. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry = Journal de l’Academie canadienne de psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent, 17(3), 137–144. Retrived on 27/02/22, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2527766/pdf/0170137.pdf

Fazel, S., & Runeson, B. (2020). Suicide. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382, 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1902944

González González Durán, J. (2021). Autopsia del suicidio en Yucatán. BSc Dissertation, Centro de Investigacion y Docencia Economicas (Mexico). Retrived on 27/02/22, https://www.proquest.com/openview/5fddaa063efe8a0b8c3863d9c66690e0/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Garbus, P., González-Forteza, C., Cano, M., Jiménez, A., Juárez-Loya, A., & Wagner, F. A. (2022). Suicidal behavior in Mexican adolescents: A test of a latent class model using two independent probability samples. Preventive medicine, 157, 106984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.106984

González, R. M. M. (2010). Condiciones de vida y salud en zonas indígenas de Yucatán, México: 1990 y 2005. Población y Salud en Mesoamérica, 8(1), 3. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3259472

Hair, F. J., Hult, G. T., Ringle, C., Sarstedt, M., Hair, F. Jr., Tomas, G., & Hult, M. (2016). Christian Ringle, Marko Sarstedt.SAGE Publications.

Harris, K. M., Syu, J. J., Lello, O. D., Chew, Y. E., Willcox, C. H., & Ho, R. H. (2015). The ABC’s of suicide risk assessment: Applying a tripartite approach to individual evaluations. PLoS One, 10(6), e0127442. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127442

Hernández-Torrano, D., Ibrayeva, L., Sparks, J., Lim, N., Clementi, A., Almukhambetova, A., Nurtayev, Y., & Muratkyzy, A. (2020). Mental health and well-being of University students: A bibliometric mapping of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01226

Hughes, A. J., Dunn, K. M., Chaffee, T., Bhattarai, J., & Beier, M. (2018). Diagnostic and clinical utility of the GAD-2 for screening anxiety symptoms in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 99(10), 2045–2049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2018.05.029

Iasiello, M., Van Agteren, J., & Cochrane, E. M. (2020). Mental health and/or mental illness: A scoping review of the evidence and implications of the dual-continua model of mental health. Evidence Base, 2020(1), 1–45. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.261420605378998

Iliceto, P., Pompili, M., Lester, D., Gonda, X., Niolu, C., Girardi, N., Rihmer, Z., Candilera, G., & Girardi, P. (2011). Relationship between temperament, depression, anxiety, and hopelessness in adolescents: A structural equation model. Depression Research and Treatment, 2011, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/160175

James, S. L., Abate, D., Abate, K. H., Abay, S. M., Abbafati, C., Abbasi, N., & Briggs, A. M. (2018). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet, 392(10159), 1789–1858. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

Jung, J. S., Park, S. J., Kim, E. Y., Na, K. S., Kim, Y. J., & Kim, K. G. (2019). Prediction models for high risk of suicide in Korean adolescents using machine learning techniques. PLoS one, 14(6), e0217639. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217639

Kato, T. (2014). Insomnia symptoms, depressive symptoms, and suicide ideation in Japanese white-collar employees. International journal of behavioral medicine, 21(3), 506–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-013-9364-4

Keyes, C. L. (2013). Promoting and protecting positive mental health: Early and often throughout the lifespan. Mental well-being (pp. 3–28). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5195-8_1., Dordrecht.

Koivumaa-Honkanen, H., Kaprio, J., Honkanen, R., Viinamki, H., & Koskenvuo, M. (2004). Life satisfaction and depression in a 15-year follow-up of healthy adults. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(12), 994–999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-004-0833-6

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Kusier, A. O., & Folker, A. P. (2020). The Well-Being Index WHO-5: hedonistic foundation and practical limitations. Medical humanities, 46(3), 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2018-011636

Kuss, D. J., Kristensen, A. M., & Lopez-Fernandez, O. (2021). Internet addictions outside of Europe: A systematic literature review. Computers in Human Behavior, 115, 106621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106621

Lenz, B., Röther, M., Bouna-Pyrrou, P., Mühle, C., Tektas, O. Y., & Kornhuber, J. (2019). The androgen model of suicide completion. Progress in Neurobiology, 172, 84–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2018.06.003

Lopez-Castroman, J., Baca-Garcia, E., authors, W. O. R. E. C. A., Courtet, P., & Oquendo, M. A. (2015). A cross-national tool for assessing and studying suicidal behaviors. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(3), 335–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2014.981624

Lustig, S., Kaess, M., Schnyder, N., Michel, C., Brunner, R., Tubiana, A., & Wasserman, D. (2022). The impact of school-based screening on service use in adolescents at risk for mental health problems and risk-behaviour. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-01990-z

Martinez-Nicolas, I., Castañeda, P. E. A., Molina-Pizarro, C. A., Franco, A. R., Maya-Hernández, C., Barahona, I., & Barrigón, M. L. (2022). Impact of depression on anxiety, well-being, and suicidality in Mexican adolescent and young adult students from Mexico City: a mental health screening using smartphones. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 83(3), 40447.

McLean, C. P., Asnaani, A., Litz, B. T., & Hofmann, S. G. (2011). Gender differences in anxiety disorders: Prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(8), 1027–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006

Moss, S. (2009). Fit indices for structural equation modeling. Retrived on 27/02/22, https://www.sicotests.com/psyarticle.asp?id=277

Mundt, J. C., Greist, J. H., Jefferson, J. W., Federico, M., Mann, J. J., & Posner, K. (2013). Prediction of suicidal behavior in clinical research by lifetime suicidal ideation and behavior ascertained by the electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 74(9), 887–893. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08398

Nadorff, M. R., Nazem, S., & Fiske, A. (2011). Insomnia symptoms, nightmares, and suicidal ideation in a college student sample. Sleep, 34(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/34.1.93

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2017). PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students’ Well-Being. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), & Education, H. (2019). Higher Education in Mexico: Labour Market Relevance and Outcomes. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264309432-en. Retrived on 06/05/22, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/higher-education-in-mexico_9789264309432-en

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2020). Better Life Initiative: Measuring Well-Being and Progress. In Statistics (Ber). Retrived on 27/02/22, https://www.oecd.org/statistics/better-life-initiative.htm

Ogrodniczuk, J. S., & Oliffe, J. L. (2011). Men and depression. Canadian Family Physician, 57(2), 153–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/0198-8859(87)90097-8

Oliffe, J. L., & Phillips, M. J. (2008). Men, depression and masculinities: A review and recommendations. Journal of Men’s Health, 5(3), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jomh.2008.03.016

Pacak-Vedel, A., Christoffersen, M., & Larsen, L. (2021). The Danish Purpose in Life test‐Short Form (PIL‐SF): Validation and age effects. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62(6), 833–838. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12776

Plummer, F., Manea, L., Trepel, D., & McMillan, D. (2016). Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: A systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 39, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005

Posner, K., Brown, G. K., Stanley, B., Brent, D. A., Yershova, K. V., Oquendo, M. A., Currier, G. W., Melvin, G. A., Greenhill, L., Shen, S., & Mann, J. J. (2011). The Columbia–suicide severity rating scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(12), 1266–1277. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704

Reyes-Foster, B. (2013). The devil made her do it: Understanding suicide, demonic discourse, and the social construction of ‘Health’ in Yucatan, Mexico. Journal of Religion and Violence, 1(3), 363–381. https://doi.org/10.5840/jrv2013137

Ridner, S. L., Newton, K. S., Staten, R. R., Crawford, T. N., & Hall, L. A. (2015). Predictors of well-being among college students. Journal of American College Health, 64(2), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2015.1085057

Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x

Sareen, J., Cox, B. J., Afifi, T. O., De Graaf, R., Asmundson, G. J., Have, T., M., & Stein, M. B. (2005). Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(11), 1249. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249

Sekhar, D. L., Schaefer, E. W., Waxmonsky, J. G., Walker-Harding, L. R., Pattison, K. L., Molinari, A., Rosen, P., & Kraschnewski, J. L. (2021). Screening in high schools to identify, evaluate, and lower depression among adolescents. JAMA Network Open, 4(11), e2131836. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.31836

Sigfusdottir, I. D., Kristjansson, A. L., Thorlindsson, T., & Allegrante, J. P. (2016). Stress and adolescent well-being: The need for an interdisciplinary framework. Health Promotion International, daw038. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daw038

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Stallman, H. M. (2010). Psychological distress in university students: A comparison with general population data. Australian Psychologist, 45(4), 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2010.482109

Storrie, K., Ahern, K., & Tuckett, A. (2010). A systematic review: Students with mental health problems-A growing problem. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2009.01813.x

Swendsen, J. (2000). The comorbidity of depression and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00026-4

Thompson, E. A., Mazza, J. J., Herting, J. R., Randell, B. P., & Eggert, L. L. (2005). The mediating roles of anxiety, depression, and hopelessness on adolescent suicidal behaviors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35(1), 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.35.1.14.59266

Topp, C. W., Østergaard, S. D., Søndergaard, S., & Bech, P. (2015). The WHO-5 well-being index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(3), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1159/000376585

Velázquez-Vázquez, D., Rosado-Franco, A., Herrera-Pacheco, D., & Méndez-Domínguez, N. (2019). Epidemiological description of suicide mortality in the state of Yucatan between 2013 and 2016. Salud Mental, 42(2), 75–82. Retrived on 27/02/22, https://www.medigraphic.com/cgi-bin/new/resumenI.cgi?IDREVISTA=81&IDARTICULO=87019&IDPUBLICACION=8330

von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2007). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. The BMJ, 33, 806–808. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD

Westerhof, G. J., & Keyes, C. L. (2010). Mental illness and mental health: The two continua model across the lifespan. Journal of adult development, 17(2), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9082-y

Wood, A. M., & Joseph, S. (2010). The absence of positive psychological (eudemonic) well-being as a risk factor for depression: A ten year cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 122(3), 213–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.032

World Health Organization (WHO). (2013). Health 2020, A European policy framework and strategy for the 21st century. WHO: Geneva.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. WHO: Geneva.

Zhang, J., Liu, X., & Fang, L. (2019). Combined effects of depression and anxiety on suicide: A case-control psychological autopsy study in rural China. Psychiatry Research, 271, 370–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.010

Acknowledgements

Partially supported by UNAM PAPIIT Project IN108216.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors of this research article have participated in the study and have collaborated in writing and/or revision tasks; all have agreed that the work is ready for submission to this journal and accept responsibility for the manuscript’s contents. The specific contributions of each author are as follows: Ismael Martinez-Nicolas and Cristian Antonio Molina-Pizarro contributed to the design of the study, data analysis supervision, and the drafting and revision of the paper. Arsenio Rosado Franco designed data-collection tools, participated in fieldwork, and drafted the paper. Pavel E. Arenas Castañeda designed data-collection tools, participated in fieldwork, and revised drafts of the paper. Cynthya Maya contributed to the design of the study, the search and review of the literature, and revised the paper. Igor Barahona cleaned and analysed the data and drafted the paper. Gonzalo Martínez-Alés, Fuensanta Aroca Bisquert, Olatz Lopez-Fernandez, David Delgado-Gomez, Kanita Dervic and Enrique Baca-García contributed to the design of the study, interpretation of the data, aided in the literature search and review, and drafted the paper. María Luisa Barrigón revised the study design, interpretation of results, and drafted the manuscript. All authors have discussed the results, commented on the manuscript, and have given their final approval for the text to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

Enrique Baca-Garcia is founder of eB2. Enrique Baca-Garcia has designed MEmind.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval (001/2019) was received by the Ethics Review Board of the ‘Hospital Psiquiátrico Yucatán’, Mérida, State of Yucatán (Mexico).

Consent to participate

Consent was received before inclusion of participants in the study.

Consent for publication

All authors approved the submission of this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martínez-Nicolás, I., Molina-Pizarro, C.A., Franco, A.R. et al. What seems to explain suicidality in Yucatan Mexican young adults? Findings from an app-based mental health screening test using the SMART-SCREEN protocol. Curr Psychol 42, 30767–30779 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03686-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03686-8