Abstract

The current research treated laughter as an indexical with two closely allied properties: to designate talk as non-serious and to serve as a mode of address signalling a preference for solidarity. These properties gave rise to four discrete forms of laughter bout, solitary speaker, solitary listener, speaker-initiated joint, and listener-initiated joint laughter, which were examined using 55 same-gender pairs discussing three choice dilemma items. By exploring the associations between the wider contextual factors of familiarity, gender, disagreement and status, and the frequencies of each form of bout within the dyad, it was hoped to establish whether laughter was related to how participants modulated their social relationships. Neither familiarity nor disagreement had any effect on any of the forms of laughter bout, while females were found to demonstrate higher frequencies of joint speaker laughter than males. In unequal status pairs, high status female staff joined in the laughter of their low status female student interlocutors less often than the reverse, a finding comparable with the exchange of other terms of address, such as second person pronouns in European languages. It was concluded that joint laughter was a signal of solidarity and solitary speaker laughter was a declared preference for solidarity, but the significance of solitary listener laughter, beyond an acknowledgement of the speaker’s non-serious talk, remained less clear. It was also noted that norms associated with the setting and topic of interaction were influential in determining the extent to which laughter would be used to modulate the relationships between interlocutors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Traditionally, laughter has been seen as a simple expression of emotion, typically joy, prompted by a humorous act or event (e.g., Darwin, 1872/1979). Recent research adopting a wider perspective has shown that laughter may both reflect and elicit the positive, prosocial affect associated with effective social relationships. The tendency for women to laugh more than men during speech (e.g., Provine, 1993), the association between friendship and joint laughter (e.g., Owren & Bachorowski, 2003), and even the relationship between laughter and social dominance (e.g., Oveis et al., 2016) have all been explained in terms of laughter connoting a positive social emotion.

A second, distinct research tradition emerged from findings that only a small proportion of talk preceding laughter could be classed as “funny” (Provine, 1993, 2000) and concentrated on the role of laughter during everyday interaction. Partington (2006), for example, found that laughter could follow expressions of gratitude, evaluations, both positive and negative, simple statements of fact, and even derogatory remarks. Critically, however, as Glenn (2003) comprehensively demonstrated, laughter does not occur randomly during talk and may act as a form of oral punctuation (Provine, 2017). At the same time, the spontaneous, emotionally toned laughter that occurs during everyday conversation can be reliably distinguished from ‘spoken’, volitional laughter (Brown et al., 2018; Bryant & Aktipis, 2014). It follows that while laughter might be best understood as constituting an important part of everyday interaction, it cannot be examined as just another word or part of speech. Nonetheless, the position that laughter has been ‘co-opted’ into spoken discourse is now broadly accepted by a range of biologically oriented authorities such as Provine (2017), Bryant et al. (2016), and Gervais and Wilson (2005).

A possible way of accounting for laughter as part of interaction that also offers scope for explaining laughter’s role in modulating interpersonal relationships is to follow Van Hooff (1972). Based on his understanding of the phylogeny of laughter in primates, Van Hooff argued that laughter in humans serves a meta-communicative function that signals the non-seriousness nature of the behavior with which it is associated (p. 235). This implies that during interaction the person laughing signals to the listener that whatever is being said or done should be taken non-seriously, not at “face value” (Schenkein, 1972). However, the extent to which laughter is inextricably bound up with language, as opposed to operating as a discrete, emotionally-laden adjunct to language, remains contentious. The latter, ‘emotional’ position is evident in the work of biologically oriented authorities such as Provine (1993, 2000, 2017), while the former, ‘linguistic’, position is advocated by exponents of Conversational Analysis (CA) (e.g., Glenn, 2003; Jefferson, 1979; Jefferson et al., 1987). Knight (2011) sums up this problematic relationship between laughter and language by agreeing that laughter serves to qualify what is being said and done, while offering two critical caveats: first, laughter does not have ‘meaning’ in the way words do; and, second, laughter typically affects the interpersonal relationship between laugher and listener.

Laughter as an indexical

Taking Knight’s position as a starting point, it is proposed to examine laughter as an indexical: a linguistic sign, such as the personal pronoun, ‘you’ or the demonstrative pronoun, ‘that’, which only make sense in the linguistic and social context in which it occurs (see Widdowson, 2004). This view is closer to the CA tradition but grants laughter its peculiar status as a non-representational feature of talk that has no significance beyond the interaction in which it occurs (Provine, 2017). The notion of laughter as an indexical has been suggested by a number of authorities (e.g., Deacon, 2011; Glenn, 2003) but it was only recently that Ginzburg et al. (2020) seriously developed the perspective. The current study is intended to further develop the idea of laughter as an indexical and assess its utility in accounting for how laughter comes to be used during talk in the variety of ways that it does.

Relying on Silverstein’s (1976) analysis of indexicals, it is suggested that laughter is typically used in two closely related ways: to characterise the utterance to which the laughter is directed as non-serious and, simultaneously, to act as a mode of address that signifies a preference for solidarity with the other interactors. The terms non-serious and solidarity are employed largely for their neutrality. They lack the positive connotations of play and affiliation respectively and reflect the wide range of contexts in which laughter occurs. These two properties, a non-serious designation and a mode of address, correspond to Adelsward’s (1989) conclusion on laughter that it displayed “ ….. an attitude towards your interlocutor as well as what you are talking about” (p. 129).

Treating laughter as an indexical has significant implications for how it is examined systematically. First it requires us to distinguish speaker laughter from listener laughter. Speaker laughter qualifies the person’s own utterance, affirming that whatever has been said is not to be taken seriously, while listener laughter, when it follows talk without laughter, is confirming that the speaker’s utterance was not meant seriously. The degree of uncertainty clearly varies depending on the position of the person laughing within the conversation. As an indexical, laughter also explains why joint laughter, when one person joins in or returns the laughter of another, constitutes a distinct social signal. In joint laughter, the laughter of each person refers primarily to the laughter of the other, in most cases making good on the implied preference for solidarity.

The general aim of the current study was to determine if these different forms of laughter bout, solitary speaker laughter, solitary listener laughter and joint laughter, instigated by both speaker and listener, were associated with different social contexts and relationships. As Provine (1993, 2017) has demonstrated, the frequency of laughter is affected by a variety of contextual factors, so the refined categories of laughter bout should also vary systematically with wider contextual features (see also Wood & Niedenthal, 2018). Drawing on the extensive research into laughter from a psychological perspective, which traditionally views laughter as an expression of positive affect, the current study focussed on those contextual factors of interaction in which the extent of positive affect might be most influential: the degree of familiarity with a discussion partner, the gender of the dyad discussing the experimental issues, agreement and disagreement on the issues, and the relative status of the interlocutors. The degree to which each of these contextual aspects bears on the four forms of laughter bout is explored in more detail below.

Familiarity

Considering familiarity, there is some evidence that, under certain circumstances, the high levels of familiarity found in friendship may be associated with more laughter. Foot et al. (1977) employed pairs of seven and eight year old children who sat side by side while watching a comedy film. They found a strong association between friendship and what might best be described as listener laughter, though it was not the talk of the other which elicited the laughter but the film. Smoski and Bachorowski (2003a) found strong evidence that, compared with strangers, friends offered more frequent joint laughter but not solitary laughter during talk associated with two amusing tasks. Smoski and Bachorowski (2003b), using different game playing tasks, also found that same gender pairs of friends produced more joint laughter than same gender pairs of strangers, though male pairs of friends only did so in the second and third sessions of the task. In contrast, Vettin and Todt (2004) found limited differences in the frequency of laughter between acquaintances, who were engaged in relaxed laboratory-based conversations about “everyday life and gossip”, and strangers, who discussed an experiment in which they had participated (p. 96).

In a more direct examination of the relationship of friendship and joint laughter, Kurtz and Algoe (2017) examined the laughter of participants watching amusing animations with a confederate with whom they were not supposed to communicate. The amount of shared laughter that occurred despite the instructions correlated more strongly with self-ratings of similarity with the confederate than with self-rated emotion, though the capacity of participants to judge how often they shared laughter was limited. Kurtz and Algoe concluded that joint laughter could act as sign of emerging solidarity as well as being a product of that relationship. Adelsward (1989) also identified a relationship between emerging solidarity and laughter when she found that successful applicants following a job interview demonstrated noticeably more joint laughter than unsuccessful applicants.

It is notable that only one of the studies reviewed above employed everyday conversation (Vettin & Todt, 2004) and it found no clear link between familiarity and laughter. When friendship was associated with laughter, it occurred watching a comedy (Foot et al., 1977), or engaging in amusing tasks, such as drawing each other’s faces, making up names for a curious doll (Smoski & Bachorowski, 2003a), playing with Play-doh and reading out spam haiku (Smoski & Bachorowski., 2003b). Kurtz and Algoe (2017) showed that when strangers engage in joint laughter they see themselves as more similar but it is as yet unclear if friendship per se is consistently linked to more laughter, joint or otherwise, during mundane interaction.

Gender

The relationship between gender and laughter has also received attention. As with familiarity, there is evidence that any differences between men and women wax and wane depending on the occasion of talk and the conversational partner. Women have long been recognized to favor a more solidary, cooperative form of interaction than men (e.g., Reis et al., 1985; Strodtbeck & Mann, 1956) and would be expected to show more laughter generally, irrespective of their conversational partner. Grammer (1990) demonstrated that women typically offer more speaker laughter than men. Provine (1993, 2000) observed that women offered consistently high amounts of laughter when speaking to both women and men, lower amounts of laughter when listening to men, and much less laughter when listening to women. Men, on the other hand, demonstrated less laughter when speaking to women than when speaking to men, marginally less laughter when listening to men, and least laughter when listening to women. Clearly both the conversational position of speaking and listening and the gender of the interlocutor have marked effects on the amount of laughter offered by men and women.

In marked contrast to the Provine study, Martin and Gray (1996) found that men and women laughed at equal rates to a comic audio tape, both when taped audience laughter was present, creating a form of joint listener laughter, and when it was absent, effectively solitary listener laughter. Smoski and Bachoroski (2003a) found no gender differences in joint laughter in same gender pairs performing their highly ‘amusing’ tasks nor did Smoski and Bachorowski (2003b), apart from the first session of their longitudinal study when pairs of female friends engaged in more joint laughter than pairs of male friends. Finally, Vettin and Todt (2004) found no difference between the genders when all types of laughter were combined during their casual conversations and experimental debriefings. Adelsward (1989) identified a greater tendency for female applicants to join in the laughter of an interviewer when compared with men but no evidence has been found with respect to joint laughter in same gender interaction.

In summary, there is some support for the general finding that women tend to offer consistently more laughter when speaking when compared to men, but rates of listener laughter depend heavily on the interlocutor and type of interaction. There is a suggestion that women may be more inclined than men to join in the laughter of the other but it seems likely that this also depends heavily on who that other is.

Status

There have been a number of studies suggesting a relationship between status and differences between interlocutors as to who joins in with whom during joint laughter. Employing mainly qualitative methodologies, Coser (1959), West (1984) and Haakana (2002) all found that during interactions between doctors and patients, patients laughed more often, largely because patients nearly always reciprocated the laughter of doctors but the reverse was infrequent. The same pattern of asymmetrical reciprocation was revealed in a study by Sekhon (1993), who only examined female dyads, with female university students joining the laughter of female university staff much more frequently than they did when talking to other female students. Finally, Adelsward’s (1989) comprehensive analysis of laughter during interviews with fraudsters showed that the defendant initiated five times as many of the reciprocated exchanges of laughter than did the interviewer. Glenn (2010), investigating laughter during employment interviews, established that the interviewees joined in the laughter of the interviewers more often than interviewers joined in the laughter of the interviewees.

Haakana (2002) and Glenn (2010) stress the roles of the doctors and interviewers in accounting for these asymmetries but a more parsimonious explanation can be taken from Brown and Gilman’s analysis of another pair of indexicals in European languages, the socially close or ‘intimate’ T version of the second person pronoun and the more distant, V version. The TV pair was also found in English as Thou and You but dropped out of common usage around the 17th C. Brown and Gilman’s (1960) seminal paper argued that high status persons were more likely to address each other using the socially distant V variant signifying equality and social distance, while lower status persons used the close T version signifying equality and solidarity. More relevant to the current discussion is that a higher status person could address a social inferior using T, but would expect V in turn. Similar asymmetric forms of address have been observed in the use of nick names and actual names (Brown & Ford, 1961), in the use of first and family names or titles in West’s (1984) study of doctors and patients, and in the use of both names and the TV forms of “you” in Adelsward et al. (1988) study of Swedish courtroom interactions. Importantly, in extending the notion of asymmetric TV forms of address to modern usage it must be recognised that in the 17th C social status was largely fixed, while, today, the status associated with roles is both achieved and largely situated. Thus, the extent to which a doctor or judge is accorded superior status outside the surgery or courtroom, or even within these situations during talk unrelated to work, is likely to vary.

Notwithstanding this variability, it appears that during role related interaction, the system of asymmetric exchange may hold with laughter. The data suggest that the instigator of a solidary sign of joint laughter typically occupies the higher status role, such as doctor, academic staff member, or interviewer. This suggests that the occupant of the lower status role in the interaction, patient, student, or interviewee, regularly joins in the laughter of the higher status interlocutor producing frequent signs of solidarity initiated by the higher status person. On the other hand, the higher status interlocutor, the doctor for example, generally fails to join in the laughter of the lower status patient, thus, the latter instigates fewer signs of solidarity. Both parties are working together to ensure that during interaction, it is the higher status role occupant who provides more of the solidary signs than the lower status occupant, in an analogous manner to the exchange of pronouns and names.

Agreement and disagreement

In the only study found that investigated laughter and disagreement, White and Reavis (1981) identified significantly higher levels of general laughter during principal-teacher interactions when there was more marked disagreement over the subordinate’s role. White and Reavis attributed this to higher levels of anxiety with laughter serving to reduce tension (e.g., Chapman, 1975a, b). Importantly, these discussions did not occur during work but were used as part of a problem-solving task, a situation which allowed for some ‘play’. An alternative account based on laugher as an indexical would suggest that laughter served to downplay the seriousness of the disagreement in order to sustain an appropriate degree of social solidarity. Serious disagreement would presumably be linked to little or no laughter. In the course of the current study it proved possible to explore the effects of agreement and disagreement on the differing forms of laughter.

Aims and hypotheses

The foregoing review has explored the associations between the wider contextual factors of familiarity, gender, status, and disagreement and three principal forms of laughter bouts, solitary speaker, solitary listener and joint laughter. It was hampered by the very few studies that have actually distinguished solitary speaker and solitary listener laughter but has revealed a range of varied findings. Consequently, there was some advantage to be gained by further investigation of the more refined classification of laughter bout prompted by treating laughter as an indexical. Only by establishing that the different forms of laughter bout are associated with more obvious and defensible contextual factors such as familiarity, gender, and status can the significance of the different bouts be established. The current study employed an experimental interaction which was intended to be more similar to everyday talk than the fun and games tasks usually employed in studies of laughter. Participants were asked to engage in a series of dyadic discussions concerning life dilemmas, many of them life changing, about which participants either agreed or disagreed. Though the topics were important and value laden, they took place as part of research in a university setting, not unlike the work-related discussions of White and Reavis mentioned above. Goffman (1974), in his analysis of interaction key, notes that experiments are not ‘real life’ and an element of play will inevitably be involved. Apart from the obvious problem of gathering the sort of detailed information required outside the laboratory, the aspect of play inherent in the experiment was considered advantageous in so far as serious talk about serious issues would probably lead to no laughter at all.

Given the complexity and incompleteness of the quasi-experimental design, it proved expedient to consider the study as comprising three parts. The first, preliminary part of the study involved the exploration of any relationships between agreement and disagreement and the four forms of laughter bout, solitary speaker, solitary listener, and joint laughter, the latter subdivided into speaker-initiated and listener-initiated joint laughter. The last distinction is novel but the rigorous application of laughter as an indexical entailed the exploration of when the listener joins in the speaker laughter and when the speaker joins in the listener laughter.

In the second part of the study the effects of familiarity and gender were examined in relation to the four forms of bout. It was expected that, following Smoski and Bachorowski (2003a, b), the more familiar dyads, in keeping with their greater solidarity, would show higher rates of both forms of joint laughter but not necessarily solitary laughter. This represented an extension of the effects of familiarity from the laughter-rich exercises of Smoski and Bachorwoski to more serious talk. The second prediction concerned gender, despite its failure to have consistent effects in the various studies. It was expected that when discussing serious issues in the laboratory, female gender pairs would have more opportunity to demonstrate their general preference for more cooperative, less distant form of interaction and show higher rates of joint laughter, than male same gender pairs. The relationship between gender and solitary laughter is less clear. Female pairs could conceivably engage in more solitary speaker laughter given it may signal a preference for solidarity, while there is a suggestion that male pairs might offer more solitary listener laughter as they signal a weaker preference for solidarity elicited by their partner’s talk.

In the third part of the study, the principal focus was on the unequal status conditions, in which a higher status staff member interacted with lower status student, in an effort to establish if any of the four forms of laughter bout were associated with the relative status of the interlocutor. The design of the study also allowed additional comparisons between staff who occupied a higher status role, when talking to a student, and staff in an equal status role when interacting with another member of staff. It was also possible to compare students occupying a lower status role when talking to staff, with students in an equal status role when talking to another student. It was anticipated that the differing levels of status would be associated with asymmetries in the manner in which laughter was exchanged. Specifically, it was predicted that staff in a higher status role would initiate more joint laughter than students in a low status role.

Confirmation of the predictions would constitute support for the importance of distinguishing between bouts of laughter in terms of its indexical properties and show how the second property, laughter as a mode of address, is particularly relevant to solidarity and status. It was also hoped that the data would demonstrate that it is not just laughter per se that modulates these relationships but how laughter is exchanged between interlocutors.

Method

Participants

One hundred and ten students and staff from of a small Australian regional University completed a study of communication patterns. The students were generally aged between and 18 and 21 and were drawn from a variety of disciplines but mainly psychology, the social sciences, and nursing. Staff varied widely in age, from around 30 to 55, and were drawn from a similar mix of disciplines to the students. The spread of age and background of both staff and students was comparable for males and females. All participants spoke English in the home.

Design

The study concerned only same gender pairs so the following procedural steps took place for females and males separately. Initially, all academic staff and students who had volunteered were randomly allocated to the six equal status conditions within which familiarity was to be examined, and to the two unequal status conditions. In the equal status conditions, three differing levels of familiarity were created. To produce high familiarity pairs, a randomly selected group of students were asked if they could bring to the study a same-gendered partner who attended the university whom they knew well or moderately well. Medium familiarity conditions comprised acquaintances; staff paired with another staff member of the same gender from a different school. Given the relatively small size of the institution it was not possible to pair staff with complete strangers. The use of staff as acquaintances ran the risk of confounding age and experience with familiarity but in the absence of research demonstrating any effects of age and experience on laughter, the risk was deemed acceptable. In the low familiarity, stranger, conditions, students were paired with a student of similar age and gender from another program. Assigning participants to these six conditions resulted in 37 equal status dyads, distinguished according to the gender of the dyad and the degree of familiarity between each member of the dyad, low, medium, and high (see Table 1).

In the two unequal status conditions, each pair comprised a randomly selected member of the academic staff paired with a same gender student from a program with which the staff member had no association. This resulted in 18 unequal status dyads, ten female and eight male, each dyad consisting of a high status staff member and a low status student, neither of whom was familiar with the other (see Table 1).

Materials

Apparatus

Each member of a dyad was recorded on a split screen video via cameras mounted on the wall of the laboratory. Cameras recorded a three quarters profile of each participant and video sound was recorded via a flat pressure zone microphone on the table separating the two participants. In addition, each member of the dyad was also recorded via a lapel microphone onto a separate channel of a Sony reel-to-reel tape recorder. Participants were obviously aware of both modes of recording though the actual recording devices were housed and operated from an adjoining laboratory.

Questionnaires

Participants completed a short, preliminary details form on which they recorded their gender, age group (18–21, 22–25, 26–35 or over 35), language spoken at home, and how well they knew their conversational partner on a five-point scale of familiarity from 1 (A—Your partner was completely unknown to you before today) to 5 (E – you are a very good friend of your partner and know him / her very well. You talk to your partner very frequently).

Decision making questionnaire

This comprised a set of 8 life dilemma items, seven drawn from the Kogan and Wallach Choice Dilemma Questionnaire (CDQ) (see Myers & Lamm, 1976), and one additional item concerning a choice of holidays in the same tone and format as the others but devised by the experimenter. Each item consisted of a short paragraph describing a situation in which the central character is faced with a difficult choice between a “cautious” course of action, which has a likely outcome of moderate value to the character, and a “risky” course of action, which could lead to a highly desirable outcome but might well lead to a very undesirable outcome. One example has a very intelligent and musically gifted school student choosing between a career as a concert pianist and a medical career, the former offering high status and rewards if successful, the latter offering less reward and status but with a much higher likelihood of success. The decisions cover a range of situations from choosing a partner in marriage to the selection of a holiday. All items were amended slightly to set them in an Australian context. Participants were required to read each item and then recommend to the central character either the risky or the cautious course of action. They also had to say how confident they were in that recommendation by marking a 100 mm line labeled Extremely Confident and Not confident at all at the extremes.

After the initial decisions and ratings had been completed independently, a sub-set of four of these items was presented to the pair of participants to discuss and reach a joint decision on the course of action that should be recommended to the central character. The first item was used as a warm-up exercise so that participants could get used to the apparatus and task while the subsequent three items were selected such that participants had initially made the same decision on two items but not on a third. The pair had to reach agreement on a seven-point scale from Strongly Recommend P (the cautious course of action) to Strongly Recommend Q (the risky choice). There was a middle Are undecided point for participants who could not agree, though participants rarely took this option. Immediately after the joint recommendation, participants had to provide their current decisions and confidence ratings.

Laughter bouts

Complete transcripts of the discussions on the three critical items held by each pair were made. The sound and visual tracks of the videotape were scrutinized for each instance of laughter. A laugh was defined as an audible gesture produced by a single or multiple rapid exhalations of air with the mouth and lips assuming a smile like posture (van Hooff, 1972, p. 234). This corresponds directly with Darwin’s definition: "…short, interrupted, spasmodic contractions of the chest…" and (of the mouth) "…with the corners drawn much backwards, as well as a little upwards" (Darwin, 1872/1979, p. 202). A laugh could be constituted by a single outburst (e.g., a snort) or an extended series of staccato outbursts. On occasions, the latter would still be counted as a single episode of laughter even if it were interrupted by an extended period of silence when the laugher breathed in. The laugh was deemed to be complete when breathing returned to a normal rate and volume.

The use of an audio recording which could be slowed to a half or a quarter of its normal speed was critical in allowing a detailed transcript of the talk and the subsequent determination of who was holding the floor when the first instance of laughter occurred. Since very few turns are disputed during dyadic conversations of this type, the distinction between speaker and listener laughter hinged on whose substantive talk preceded or occurred with the laughter. When the first instance of laughter occurred within or concluded a speaking turn, it was classed as speaker laughter. When the first laughter occurred when the other was talking or immediately after the other had finished his or her turn, then it was classed as listener laughter.

After the identification of a laugh, two further aspects of a bout of laughter were scrutinized: Whether the second person “joined in” the laugh; and, if this was the case, confirmation of who initiated the bout of joint laughter. Taking the latter aspect first, the person attributed with initiating the laugh was simply the participant who produced the first detectable sound of a bout of laughter as defined above. This may seem an obvious point but on occasions in which both persons laugh, the interval between the first laugh beginning and the second can be less than 500 ms. In determining whether the laugh was joint, the laughter of the second person had to overlap the initial laugh or occur early in the turn immediately following the laugh in close temporal proximity to the first laugh. This might appear a generous definition of joint laughter including both overlap and rapid reciprocation but the existence of no more than a handful of words between the initial speaker laugh at the end of a turn and the second laugh very early in the next turn was not deemed sufficient to designate the second laugh as a separate solitary speaker laugh.

The coding procedure resulted in four forms of laughter bout: solitary speaker laughter, solitary listener laughter, joint speaker (initiated) and joint listener (initiated) laughter. As a check on coding reliability, six pairs of participants were selected at random and a second investigator coded the frequencies of all four forms of laughter bout for each participant in the pair. Comparison of the frequencies in each category produced by the two coders produced a Cohen’s κ = 0.75, which is generally seen as ‘substantial’ agreement (McHugh, 2012).

Measures

Having identified all instances of each of the four forms of bouts of laughter, solitary speaker, solitary listener, joint speaker, and joint listener, the total number of instances of laughter bout for each item of discussion was determined for each participant as well as the time devoted to the discussion of that item. The rate of each of the four forms of laughter bouts was then calculated as the number of instances of each form per minute for each item. In addition, the number of instances for each pair was computed to produce for each of the three items, four equivalent dyadic rate measures, one for each form of laughter bout.

Procedure

On arrival, participants were shown into the laboratory in pairs and seated on either side of small table facing each other. Participants then completed the preliminary details form requesting their age, familiarity with their partner and language spoken at home, and then the general nature of the tasks was explained to them in written and spoken form. During this introduction it was made clear to participants as to whether they were students or staff.

The recording apparatus was displayed and the lapel microphones attached. Participants were then asked to complete the acquaintance measure and the eight choice dilemma items in silence. They were aware that they would be discussing these and that their discussions would be recorded. When both participants had finished the items, the experimenter removed their completed questionnaires to make his selection of the four items they were to discuss: a randomly selected warm up item and three critical items. The first and last of these critical items were always items about which they had agreed, while the second featured an item about which they had disagreed. They were not aware of the basis of the selection, only that they had to discuss a range of the items. They were given their completed questionnaires for reference and the experimenter explained how they had to reach agreement on the new scale that was provided for each item. The experimenter then left the laboratory though participants knew their discussion was being monitored in the next room. If participants had failed to agree on an item after around five minutes, the experimenter tapped on the window of the laboratory to indicate they had to reach a compromise and move to the next item. This occurred in only about 7% of the items discussed, principally during disagreement where the longest discussion took eight minutes.

Results

Four rate measures, laughter bouts per minute, were calculated for each participant and each dyad (see Measures), one for each form of laughter bout for each of the three items. A preliminary analysis examined whether rates of each form of laughter bout varied depending on whether there was agreement or disagreement within the dyad about the initial decision on an item. Two dyads agreed on all three items and were omitted from this analysis. For the remaining 53 dyads, the rate of each type of laughter per dyad for the two items about which they agreed was compared with the rate of each type of laughter about which they disagreed. Given the skewed nature of these two sets of four rates of laughter, the log transformation of the raw rate plus 0.1 was used.

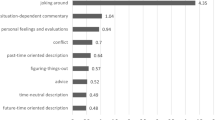

The results of a MANOVA on the four dyadic rate measures of laughter with agreement / disagreement the within dyad factor and gender and conditions as the between dyad factors, revealed a weak and insignificant multivariate effect of disagreement, F(4, 42) = 1.59, p = 0.2, partial η2 = 0.13, and a marginally stronger though still insignificant multivariate effect of gender, F(4, 42) = 1.91, p = 0.13, partial η2 = 0.15. The condition factor was not significant, nor any of the interactions. On the basis of this analysis, a single set of measures was derived by summing the instances of laughter in each form of bout across all three items, including the two pairs of participants who agreed on all three items. These totals were then transformed into rate per minute measures using the total discussion time for all three items. This resulted in each participant and each dyad having a rate of laughter incidence for each of the four forms of laughter bout. Both sets of rates were skewed so log transformations were employed in all analyses of laughter though, for the sake of clearer exposition, tabulated data comprise raw rates of laughter bouts per minute.

Consideration of the effect of familiarity was confined to the equal status conditions: student strangers (low familiarity), staff acquaintances (medium familiarity), and student friends (high familiarity). Initial analyses of the familiarity ratings (Table 1) confirmed that the manipulation of familiarity was successful, F (2, 31) = 122.7, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.89 with unfamiliar students (M = 1.05) differing significantly from partly familiar staff (M = 2.46), t = 6.34, who in turn differed significantly from very familiar students (M = 4.57), t = 9.56, tcrit = 3.15, p < 0.01. There was no effect of gender on familiarity ratings, F (1, 31) = 0.004, nor any interaction between gender and familiarity, F (2, 31) = 0.08.

Before examining the effect of familiarity on rates of laughter and in keeping with the recommendations of Kenny et al. (2006), four intraclass correlations were computed to determine the extent to which participants within a dyad were independent of one another with respect to each of the four forms of laughter bout. Controlling for effects of gender and familiarity, the analyses revealed that solitary speaker laughter showed no evidence of dependence, r ICC = -0.02, F(37,31) = 1.05, p = 0.45. Solitary listener laughter was problematic in demonstrating more variability within the dyad than between the dyads, r ICC = -0.37, F(37,31) = 3.16, p < 0.001. Both joint bouts showed clear signs of dependence following Kenny et al.’s advice of using a liberal alpha of 0.20: joint speaker laughter, r ICC = 0.23, F(37, 31) = 1.61, p = 0.08; joint listener laughter, r ICC = 0.33, F(37, 31) = 2.00, p = 0.02.

On the basis of the ICC results, two separate MANOVAs on the four rates of laughter bout were performed. Individual participant rates were used for the two solitary bouts of laughter and dyadic rates were used for the two joint bouts. Notwithstanding the negative ICC for solitary listener laughter, this was deemed the most powerful acceptable test of familiarity. Gender was included as the second between subject factor. The raw rates per participant for each of the two solitary bouts of laughter and rates per dyad for each of the two joint bouts of laughter are reported in Table 2 for each of the six conditions (Familiarity x Gender); log transformations were used in the actual analyses.

The MANOVA on the two solitary bouts of laughter, revealed there was no multivariate effect of either familiarity, Λ = 0.99, F(4,134) = 0.25, p = 0.91, or gender, Λ = 0.960, F(2,134) = 1.39, p = 0.26, nor any interaction, Λ = 0.92, F(2,134) = 1.49, p = 0.21. Univariate analyses of solitary speaker and solitary listener laughter confirmed the general absence of any significant effects of familiarity or gender, nor were there any interactions. The only result which approached significance was for females to show a higher rate of solitary speaker laughter than males, F(1, 68) = 2.72, p = 0.10, partial η2 = 0.04.

The second MANOVA, performed on the rates of the two joint bouts per pair, again found no evidence of a multivariate effect of familiarity Λ = 0.92, F(4, 60) = 0.63, p = 0.64, but the effect of gender approached significance, Λ = 0.84, F(2, 30) = 2.89, p = 0.07. There was no interaction, Λ = 0.88, F(4, 60) = 0.95, p = 0.44. Univariate analyses of rates of joint speaker and joint listener laughter demonstrated a small effect of gender on joint speaker laughter, F(1, 31) = 3.81, p = 0.06, partial η2 = 0.11, and a weak but insignificant trend in relation to joint listener laughter, F(1, 31) = 2.49, p = 0.13, partial η2 = 0.07, with females offering higher rates of both forms of joint laughter (see Table 2).

Kenny et al. (2006) are clear that when members of a dyad are distinguishable, as they are in this part of the study in terms of status, it is not necessary to investigate dependence. Nonetheless, for the sake of comparison with the equal status conditions, four intraclass correlations were computed for each of the four forms of laughter bout. Controlling for the effect of gender, the analyses revealed the following: solitary speaker laughter, r ICC = 0.13, F(18, 16) = 1.29, p = 0.30; solitary listener laughter, r ICC = -0.39, F(18, 16) = 2.25, p = 0.05; joint speaker laughter, r ICC = -0.05, F(18, 16) = 1.11, p = 0.42; joint listener laughter, r ICC = -0.18, F(18, 16) = 1.42, p = 0.24. Though the sample size is smaller than in the equal status condition, there was no evidence of dependence in any of the rates of laughter bout.

In the main analysis of status, the rates per participant of the four forms of laughter bout were examined using a MANOVA of the 18 pairs of unequal status pairs. Following Kenny et al. (2006), participant rates were entered with dyad as the unit of analysis; participant status, high (staff) vs. low (student) as the within dyad factor, and gender as the between dyad factor. The raw mean rates per participant for the four laughter bouts are found in Table 3, while the log transformation was used in the analysis.

A multivariate effect of status was found, Λ = 0.50, F(4, 13) = 3.31, p = 0.05, partial η2 = 0.50, though there was a faint suggestion of a multivariate status x gender interaction, Λ = 0.59, F(4, 13) = 2.27, p = 0.12, partial η2 = 0.04. There was no effect of gender, Λ = 0.71, F(4, 13) = 1.31, p = 0.32. Univariate analyses demonstrated a significant effect of gender on joint speaker laughter, F(1, 16) = 9.46, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.37, qualified by an interaction between status and gender, F(1, 16) = 4.44, p = 0.05, partial η2 = 0.22 (See Table 3). Tests of main effects revealed that high status female staff had a significantly higher rate of joint speaker laughter than did low status female students, F(1, 16) = 15.07, p = 0.001, but this was not the case for male staff and students, F(1, 16) = 0.41, p = 0.53. It was also noted that the interaction between status and gender approached significance for solitary listener laughter, F(1, 16) = 3.91, p = 0.07,. partial η2 = 0.20. Within female pairs, low status students offered marginally higher rates of solitary listener laughter than high status staff, F(1, 16) = 4.40, p = 0.08, but in male pairs, low status students offered less frequent solitary listener laughter than staff, though the difference was small, F(1, 16) = 0.98, p = 0.34.

It was possible to pursue the effect of status a little further using data from the equal status conditions. This allowed a simple comparison to be made between the low status students from the unequal status conditions and the students in the equal status conditions. The same could be done for staff. Given the dependence of the two measures of joint laughter in the equal status condition, the most expedient approach was to create two samples by randomly selecting one student from each pair of students in the two equal status, student conditions (friends and strangers) and one staff member from each pair in the one equal status staff (acquaintances) condition. These two samples comprising one participant from each pair in the equal status conditions could then be compared with the samples of students and staff drawn from the unequal status conditions. Two MANOVA analyses were then performed on the four rates of laughter bout, one for students and one for staff. In both analyses, status was the single between subject variable. There were no reliable differences related to status between laughter rates of staff in the unequal and equal status conditions. Among students, there was an effect of status on joint speaker laughter which was more frequent among equal status students (Mraw = 0.16), than among low status students (Mraw = 0.04), irrespective of gender, F(1, 39) = 4.34, p = 0.04, partial η2 = 0.10.

Discussion

The overall aim was to provide support for the premise that taking laughter as an indexical that has meta-communicative significance allows a more coherent account of laughter than one that relies on it being a simple expression of positive emotion. The current study examined the effect of level of agreement, familiarity, gender, and status, all of which reflect the emotional tone and relationship between participants to a degree, on the incidence of four forms of laughter bout.

The study found disagreement and familiarity had no effect on laughter but gender and status had selective effects, principally on rates of joint speaker laughter. In the equal status conditions, female pairs showed some evidence of offering more solitary speaker laughter than males and a marked tendency to engage in more joint speaker laughter. Males and females offered largely similar rates of laughter as listeners. In relation to status, male staff and students laughed in much the same way, but in female pairs, status had a significant effect on joint speaker laughter with high status staff joining in student speaker laughter less often than low status students joined in staff speaker laughter. There was also an indication that female students offered more solitary listener laughter than their staff partners. These findings together with the failure to find any effects of familiarity and disagreement require further consideration.

The failure to find any link between laughter and familiarity with the experimental partner, conflicts with a number of findings (e.g., Smoski & Bachorowski, 2003a, b) but is not unique (e.g., Vettin & Todt, 2004). Studies which identified associations of familiarity with particularly joint laughter relied heavily on experimental tasks that provided the opportunity for participants to establish a ‘play frame’ (Coates, 2007; Glenn & Knapp, 1987) during which bouts of laughter signalling non-seriousness are likely to be common. Naming plastic dolls based on Edvard Munch’s The Scream, drawing one another (Smoski & Bachorowski, 2003a), or reading each other spam haiku (Smoski & Bachorowski, 2003b) are typical of the tasks used that would lend themselves to setting up a play frame. It is suggested that in studies involving novel and unpredictable tasks, the pervasive possibility of a play frame exists, into which friends are more likely to enter than strangers. In this frame, participants familiar with each other as speakers or listeners will be more likely to return the other’s non-serious laughter marking out their solidarity with joint laughter. Phrased in the terminology of Goldsmith and Baxter (1996), participants familiar with one another are more likely to enact solidarity during experimental tasks which foster a play frame, or, at its simplest, friends are more likely to play with each other than strangers, when the situation allows.

In contrast, the current study involved a different key, a technical redoing of a discussion, rather than a playful game. Such a key might allow for occasional instances of non-serious talk but the main concern of participants, in keeping with the demand characteristics of the study, was to engage in a discussion of some ‘serious’ issues such careers or going into politics. Compared with the games of Smoski and Bachorowski (2003a & b), the task was more predictable and manageable and moves into a play frame were unlikely. In the absence of a ‘play frame’, laughter bore no relationship with familiarity. Goffman (1981) might describe this type of interaction as a ‘conversation’ rather than the debate that was intended. It seems reasonable that as far as laughter is concerned familiarity may be largely irrelevant to the way people converse.

The importance of a play within an experimental game is also relevant to those studies that found increasing amounts of joint activity led to higher ratings of interpersonal similarity. Kurtz and Algoe (2017) identified a close association between joint laughter and incipient friendship in studies that deployed light-hearted material. They were inclined to downplay the importance of emotions in this association (p. 61). Using a very different behavior, Tschacher et al. (2014) found the highest degree of bodily movement synchrony between pairs of strangers occurred in a ‘fun’ task, less with competitive debating tasks, and even less with cooperative debating tasks. In contexts in which sustained play is possible, some strangers will find they share a stance on the non-seriousness of an interaction and enter into a play frame. As Kurtz and Algoe found, the more joint laughter that emerges during the play, the more a participant indicates that they are similar to the other. In summary, when engaged in talk in which there are opportunities to engage in play, friends are more likely to do so, as will strangers who find they share a common stance to the talk.

The failure of the agreement and disagreement manipulation is also explicable in terms of the way in which participants approached the task. Though the Choice Dilemma items focus on some important decisions, participants are constantly aware that the interaction is a technical redoing: the characters are fictional, the situations contrived and the decisions of the participants, singly or jointly have no serious implications for the relationship between participants. Goffman (1981) expands on his notion of a conversation by noting that “…. differences in opinion (are) to be treated as unprejudicial to the continuing relationship of the participants” (footnote, p. 14). Thus, any disagreement between participants in the current study occurs in an interaction keyed as ‘unreal’ with no need for even friends to modulate their relationship using laughter.

A similar account can be offered in relation to the White and Reavis (1981) study in which principals and teachers were asked to discuss work related issues about which they disagreed, yet rates of laughter were high. It seems implausible that colleagues in serious dispute over a work matter discussed in situ would have engaged in much laughter but in the White and Reavis research the issues were embedded in a communication exercise as part of research. The key of the work related discussion was, as in the current study, a technical redoing and not ‘real’. It is conceivable that the participants, well known to one another as colleagues, could afford to treat it non-seriously, even entering into a play frame over their differing views in which laughter was a useful means of sustaining a relationship despite any participants concern regarding the actual issue. This would be analogous to occasions of humor in the work place, when colleagues temporarily enter into a play frame during the transaction of otherwise serious business (Holmes, 2006; Holmes & Marra, 2002). The laughter shared under these circumstances was held to be a means of sustaining and occasionally challenging the relationships between colleagues.

Turning to gender, it was found that females tended to offer slightly more solitary speaker and reliably offered more speaker-initiated joint laughter than did males. This is in keeping with Provine’s (1993) original findings that suggested that in same gender interaction women offer relatively more laughter when speaking compared to men, who tend to offer relatively more laughter when listening. Unfortunately, Provine’s methodology did not allow the derivation of rate variables nor for amounts of joint laughter, so direct comparisons beyond the general prevalence of speaker and listener laughter are not possible. It is also clear from other work that gender differences are heavily dependent on broader contextual factors, such as the gender of the conversational partner (Provine, 1993), which was not examined in this study, and discussion topic (Smoski & Bachorowski, 2003a, b), which was. The Smoski and Bachorowski studies were notable in finding no consistent differences in laughter rates between male and female pairs, neither solitary nor joint. The current findings may be the corollary of Smoski and Bachorowski’s success in identifying effects of familiarity. In laughter-rich, playful discussions, men appear as likely to laugh as women. In more mundane interactions, however, when the overall key allows for some non-seriousness but does not foster sustained periods of play, gender differences emerge. Women’s preference for solidarity leads them to offer more solitary speaker laughter than men as they affirm the possibility of non-seriousness. Adelsward (1989) makes the same point effectively when she suggests that solitary speaker laughter is typical of Goffman’s (1974) “keying, framing” laughter (p. 122). More frequent bouts of solitary speaker laughter also provide more frequent opportunities for listeners to join in, if they also subscribe to the moments of non-seriousness and, in so doing, close the distance between themselves and the speakers. When the listener is a woman this tendency to join in is comparatively frequent. Men tend to offer fewer laughs when speaking, reflecting their preference for more serious talk and social distance and thereby providing less opportunity for joint laughter. It is also possible that men are more reluctant to join in speaker laughter, in keeping with their aim of maintaining some distance between themselves and their interlocutors, but the evidence from this study is not conclusive. Finally, with respect to both forms of listener bouts, females and males behaved in a similar fashion. Provine’s (1993) suggestion that men are better at evoking laughter may be correct relative to their rates of laughter when speaking but there is no suggestion that women may evoke less laughter in general.

The relationship of status to rates of laughter bout was confined to female pairs and only notable in joint laughter. Nevertheless, there was a clear indication that low status students joined in the laughter of high status staff more often than high status staff joined in the laughter of low status students. Joint laughter is generally accepted as a signal of solidarity and if it is assumed that the first person to laugh instigates that signal then the asymmetrical pattern of exchange of joint laughter matches that proposed by Brown and Gilman (1960) in relation to the TV forms of second person pronouns and that proposed by Brown and Ford (1961) with respect to forms of address. The asymmetry emerges from the higher status addressing the lower status in an informal or close manner and the low status addressing the higher in a more formal or distant manner. The distinctive feature of joint laughter is that both parties work to achieve this pattern and, though it is tempting to assume that the asymmetrical pattern of exchange results from student behaviour, for example, they might simply be spending more time in the listener role, this is not borne out by the data. The comparison of high status female staff and equal status female staff reveals that overall rates of staff speaker laughter, both solitary speaker and joint speaker laughter, are similar for high status and equal status staff. This implies that the ratio of time speaking to time listening is not likely to be a major factor. The observed pattern of exchange emerges from the reduced likelihood of staff joining in the student speaker laughter rather than the increased likelihood of students joining in staff laughter as can be gleaned from the comparison of equal and low status students.

The implications of the findings in relation to bouts of solitary speaker, solitary listener, and both speaker and listener initiated joint laughter might be summarised as follows. The most common bout in this study, as it is in many other studies (e.g., Adelsward, 1989), was solitary speaker laughter, which, considering laughter as indexical, is suggested to serve as a simple positive affirmation that what the speaker has just said is not to be taken seriously. Nwokah et al. (1994) characterized the infant’s solitary speaker laughter during mother child interaction as “This is fun” (p. 33). The speaker’s affirmation of the non-seriousness of the immediate interaction content reflects the speaker’s recognition that the occasion allows for at least occasional moments of non-seriousness as well as signalling to fellow interlocutors that there is some potential for closing the social distance between them; however, to actually enhance solidarity the listener must join in.

The finding from the intraclass correlation that the rate of solitary speaker laughter of one interlocutor was independent of the other and the observation that there were about twice as a many solitary speaker laughs as there were speaker initiated joint laughs would suggest that solitary speaker laughter, in and of itself, has limited implications for the relationship between interlocutors. The idea that speaker laughter is an invitation to join in (e.g., Jefferson et al., 1987; West, 1984) and that declining an invitation would represent a distancing or disaffiliation (Davidson, 1984) does not seem tenable in everyday talk. Work on politeness (e.g., Brown & Levinson, 1987) would suggest that consistently declining invitations should reduce the number of invitations yet this does not seem to occur. Solitary speaker laughter would seem to be more declarative than invitational, and the declaration is that the speaker holds that the occasion allows for periodic moments of non-seriousness and prefers solidarity.

The significance of solitary listener laughter is less clear. The only finding peculiar to this bout was that low status females engaged in more solitary listener laughter than their high status partners. There were no gender differences in the equal status conditions where it might have been expected that males would display higher rates, though it must be recalled that Provine’s (1993, 2000) data stressed the relative proportions of speaker and listener laughter. Males in this study also showed a relatively greater preference for solitary listener laughter but they laughed less overall and so rates of listener laughter generally were similar for males and females.

From both intraclass correlations it seemed that the rate of solitary listener laughter in one interlocutor was inversely related to solitary listener laughter in the other. The most obvious explanation is that rates are related to length of time listening. Analytically, solitary listener laughter remains an acknowledgement of the speaker’s non-serious utterances. Unlike speaker laughter, which is probably more closely tied to the end of turns (see Holt, 2010), listener laughter can occur at any point during the speaker’s turn. It may therefore be more susceptible to variation in the time the other interlocutor talks. This would also explain the tendency for low status female students to offer slightly more solitary listener laughter than high status female staff, assuming the latter tended to talk for longer. Given that the listener laughter is elicited by the speaker’s utterance, it may constitute a weaker preference for solidarity relative to speaker laughter but, as with the latter, unless the speaker joins in, it would appear to have limited implications for the relationship between interlocutors.

The interpretation of joint laughter is clearer. In joint laughter, when either party follows or takes up the laughter of the other, the other party is confirming the non-seriousness of the immediate interaction which has been qualified by the first laugh. As a term of address, the laughter of the second person is directed towards the person offering the first laughter ‘realising’ the expressed preference for solidarity. This is suggested to transform the first laugh to create a distinctive bout of joint laughter. Nwokah et al. (1994) encapsulate this position when they gloss reciprocal mother–child laughter in the following terms, “If you think this is funny, so do I” (italics added; p. 33). As a social signal this bout of joint laughter marks a transient closing of the distance between the interlocutors (e.g., Coser, 1959, p. 172).

Pursuing this notion of joint laughter as a signal of solidarity, and assuming the first laugher is assumed to be the dominant party in the joint laughter (see Linnell et al., 1988), then we can account for the asymmetry between interlocutors in the frequency with which each instigates joint laughter. The asymmetry corresponds to the asymmetry found in TV pronoun use in European languages, terms of address, and, according to Brown and Levinson (1987, p. 46), a considerable range of goods and service. The basic asymmetry occurs when the high status person offers the intimate or solidary sign and receives the polite, distant sign in return. Of note, too, is that symmetrical exchange of solidary signs results in more stable close relationships and is suggested by the higher rates of joint laughter. The male preference for a more distant, formal interaction is shown by their exchange of fewer bouts of joint laughter.

Conclusions and future research

There remain considerable theoretical and methodological issues to be resolved. Methodologically, confounding staff status with intermediate level of familiarity was far from ideal but did not, in the end, prove to be a serious difficulty given the lack of effect of familiarity. The matter of general discussion context would appear to be a more problematic issue. It would appear that discussion context is critical in influencing the overall likelihood of laughter. Goffman’s (1974) notion of key was useful but more work is needed to confirm the general expectations of participants for any particular experimental task or discussion topic. Work is also needed to confirm the view that, for any particular key, some participants may opt to adopt a play frame and others not.

With respect to the four forms of laughter bouts clearly more research is required to establish the circumstances under which solitary speaker laughter might be invitational as suggested by Conversational Analysis. These circumstances encompass both the form and content of the speaker’s contribution as well as the existing relationship between speaker and listener. For instance, the content of talk designated as non-serious by speaker laughter and the existing relationship between speaker and listener may be relevant in distinguishing between different forms of laughing interaction, such as teasing (e.g., Lampert & Ervin-Tripp, 2006), mockery (Haugh, 2010), and irony (Ginzburg et al., 2020).

A different set of problems exist with respect to solitary listener laughter as a response to the speaker. It would be interesting to determine the conditions in which the male preference for more distant interaction leads to clear gender differences in solitary listener laughter. Finally, the status of listener initiated joint laughter remains obscure. It appears to operate in a similar fashion to speaker initiated joint laughter but its relatively low frequency precluded finding any connection between joint listener laughter and social status or gender.

There is also considerable research on the acoustic qualities of laughter that might well be pursued with a view to confirming the value of treating laughter as an indexical. Tanaka and Campbell (2014) were able to distinguish instances of polite and mirthful laughter taken from everyday conversation. It would be interesting to see if mirthful laughter followed particular types of utterance and to see if polite laughter was more common when speaking or when listening. Bryant et al. (2016) noted that the joint laughter of friends could be distinguished from that of strangers. Given the failure of the familiarity manipulation in this study, it is important to see if their finding can be extended to laughter in all forms of interaction beyond those used in the Bryant et al. study—a lab based discussion of a topic of the participants’ choosing such as ‘bad room-mate experiences’. Finally, and of most relevance to the current study, Oveis et al. (2016) established that dominant high status laughter was distinct from submissive low status laughter. Of particular interest was that this laughter was related to the role not the person. When low status men were assigned a high status role, their laughter became more dominant.

The Oveis et al. (2016) study prompts consideration of one of the most intractable problems in laughter research: the extent to which people ‘mean’ to laugh. Provine (2017) suggests that laughter is ‘ under weaker voluntary control than speaking’ (p. 239), though this begs the question of how much ‘voluntary control’ we might possess over each and every word we utter. It is clear that if instructed to laugh we make a poor job of it; neither, as Provine readily acknowledges, does laughter simply flood out at random. An argument could be made that what we do with laughter as speakers and listeners is attempt to modulate the overall relationship we have with others in terms of the two basic dimensions of solidarity and status. The intricacies of the relationship emerge from what we say and how we say it. Bryant et al. (2018) concluded their paper on spontaneous and volitional laughter with a view that future work should focus on how laughter and language interacts. It is hoped that the current study has provided some evidence that treating laughter as an indexical allows us to achieve this by linking laughter to both its linguistic and social context.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. A copy of the original data has been submitted as Supplementary Material.

References

Adelsward, V. (1989). Laughter and dialogue: The social significance of laughter in institutional discourse. Nordic Journal of Linguistics, 12, 107–136.

Adelsward, V., Aronsson, K., & Linell, P. (1988). Discourse of blame: Courtroom construction of social identity from the perspective of the defendant. Semiotica, 71, 261–284.

Brown, R., & Ford, M. (1961). Address in American English. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 62(2), 375–385.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language use. Cambridge University Press.

Brown, M., Sacco, D. F., & Young, S. G. (2018). Spontaneous laughter as an auditory analog to affiliative intent. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 4, 285–291.

Brown, R., & Gilman, A. (1960). The pronouns of power and solidarity. In T. A. Sebeok, (Ed.), Style in Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bryant, G. A., & Aktipis, C. A. (2014). The animal nature of spontaneous laughter. Evolution and Human Behavior, 35, 327–335.

Bryant, G. A., Fessler, D. M. T., Fusaroli, R., Clint, E., Aarøe, L., Apicella, C. L., …., Zhou, Y. (2016). Detecting affiliation in colaughter across 24 societies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 4682–4687.

Bryant, G. A., Fessler, D. M. T., Fusaroli, R., Clint, E., Amir, D., Chávez, C., …., Zhou, Y. (2018). The perception of spontaneous and volitional laughter across 21 societies. Psychological Science, 29(9), 1515–1525.

Chapman, A. J. (1975a). Humorous laughter in children. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 31(1), 42–49.

Chapman, A. J. (1975b). Eye contact, physical proximity and laughter: A re-examination of the equilibrium model of social intimacy. Social Behavior and Personality, 3, 143–155.

Coates, J. (2007). Talk in a play frame: More on laughter and intimacy. Journal of Pragmatics, 39, 29–49.

Coser, R. (1959). Some social functions of laughter: A study of humor in a hospital setting. Human Relations, 12, 171–182.

Darwin, C. (1979). The expression of emotion in man and animals. London, UK: Julian Friedmann Publishers. (Original work published 1872).

Davidson, J. (1984). Subsequent version of invitations, offers, requests, and proposals dealing with potential or actual rejection. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversational Analysis (pp. 102–128). Cambridge University Press.

Deacon, T. W. (2011). The symbol concept. The Oxford Handbook of Language Evolution. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199541119.013.0043

Foot, H. C., Chapman, A. J., & Smith, J. R. (1977). Friendship and social responsiveness in boys and girls. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 401–411.

Gervais, M., & Wilson, D. S. (2005). The evolution and functions of laughter and humor: A synthetic approach. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 80, 395–430.

Ginzburg, J., Mazzocconi, C. & Tian, Y. (2020). Laughter as language. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics, 5(1), 104, 1–51.

Glenn, P. (2003). Laughter in interaction. Cambridge University Press.

Glenn, P. (2010). Interviewer laughs: Shared laughter and asymmetries in employment interviews. Journal of Pragmatics, 42, 1485–1498.

Glenn, P. J., & Knapp, M. L. (1987). The interactive framing of play in adult conversations. Communication Quarterly, 35, 48–66.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. University Press of New England.

Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Goldsmith, D. J., & Baxter, L. A. (1996). Constituting relationships in talk: A taxonomy of speech events in social and personal relationships. Human Communication Research, 23, 87–114.

Grammer, K. (1990). Strangers meet: Laughter and nonverbal signs of interest in opposite-sex encounters. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 14, 209–236.

Haakana, M. (2002). Laughter in medical interaction: From quantification to analysis, and back. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 6, 207–235.

Haugh, M. (2010). Jocular mockery, (dis)affiliation, and face. Journal of Pragmatics, 42, 2106–2119.

Holmes, J. (2006). Sharing a laugh: Pragmatic aspects of humour and gender in the workplace. Journal of Pragmatics, 38, 26–50.

Holmes, J., & Marra, M. (2002). Having a laugh at work: How humour contributes to workplace culture. Journal of Pragmatics, 34, 1683–1710.

Holt, L. (2010). The last laugh: Shared laughter and topic termination. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(6), 1513–1525.

Jefferson, G. (1979). A technique for inviting laughter and its subsequent acceptance declination. In G. Psathas (Ed.), Everyday language: Studies in ethnomethodology. Irvington Publishers.

Jefferson, G., Sacks, H., & Schegloff, E. A. (1987). Notes on laughter in the pursuit of intimacy. In G. Button & J. R. E. Lee (Eds.), Talk and social organisation. Multilingual Matters.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Knight, N. (2011). The interpersonal semiotics of having a laugh. In S. Dreyfus, S. Hood, & M. Stenglin (Eds.), Semiotic margins: Meaning in multimodalities. Continuum.

Kurtz, L. E., & Algoe, S. B. (2017). When sharing a laugh means sharing more: Testing the role of shared laughter on short-term interpersonal consequences. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 41, 45–65.

Lampert, M. D., & Ervin-Tripp, S. M. (2006). Risky laughter: Teasing and self-directed joking among male and female friends. Journal of Pragmatics, 38, 51–72.

Linnell, P., Gustavsson, L., & Juvonen, P. (1988). Interactional dominance in dyadic communication: A presentation of initiative-response analysis. Linguistics, 26, 415–442.

Martin, G. N., & Gray, C. D. (1996). The effects of audience laughter on men’s and women’s responses to humor. The Journal of Social Psychology, 136, 221–231.

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3900052/

Myers, D. G., & Lamm, H. (1976). The group polarization phenomenon. Psychological Bulletin, 83, 602–627.

Nwokah, E. E., Hsu, H. C., Dobrowolska, O., & Fogel, A. (1994). The development of laughter in mother-infant communication: Timing parameters and temporal sequences. Infant Behavior & Development, 17, 23–35.

Oveis, C., Spectre, A., Smith, P. K., Liu, M. Y., & Keltner, D. (2016). Laughter conveys status. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 65, 109–115.

Owren, M. J., & Bachorowski, J. (2003). Reconsidering the evolution of nonlinguistic communication: The case of laughter. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 27(3), 183–199.

Partington, A. (2006). The Linguistics of Laughter: A Corpus-Assisted Study of Laughter-talk. Routledge.

Provine, R. R. (1993). Laughter punctuates speech: Linguistic, social and gender contexts of laughter. Ethology, 95, 291–298.

Provine, R. R. (2000). Laughter: A scientific investigation. Faber and Faber.

Provine, R. R. (2017). Laughter as an approach to vocal evolution: The bipedal theory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 24, 238–244.

Reis, H. T., Senchak, M., & Solomon, B. (1985). Sex differences in the intimacy of social interaction: Further examination of potential explanations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 1204–1217.

Schenkein, J. (1972). Towards an analysis of natural conversation and the sense of Heheh. Semiotica, 6, 344–377.

Sekhon, A. (1993). Reciprocated and unreciprocated laughter in mixed and equal status dyads. (Unpublished Graduate Diploma Thesis). Ballarat University College, Ballarat, VIC, Australia.

Silverstein, M. (1976). Shifters, linguistic categories and cultural description. In K. H. Basso & H. A. Selby (Eds.), Meaning in Anthropology. University of New Mexico Press.

Smoski, M. J., & Bachorowski, J. (2003a). Antiphonal laughter between friends and strangers. Cognition and Emotion, 17(2), 327–340.

Smoski, M. J., & Bachorowski, J. (2003b). Antiphonal laughter in developing friendships. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1000, 300–303.

Strodtbeck, F. L., & Mann, R. D. (1956). Sex role differentiation in jury deliberations. Sociometry, 19, 3–11.

Tanaka, H., & Campbell, N. (2014). Classification of social laughter in natural conversational speech. Computer Speech & Language, 28, 314–325.

Tschacher, W., Rees, G. M., & Ramseyer, F. (2014). Nonverbal synchrony and affect in dyadic interactions. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1323.

Van Hooff, J. A. R. A. M. (1972). A comparative approach to the phylogeny of laughter and smiling. In R. A. Hinde (Ed.), Non-verbal communication. Cambridge University Press.

Vettin, J., & Todt, D. (2004). Laughter in conversation: Features of occurrence and acoustic structure. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 28, 93–115.

West, C. (1984). Routine complications: Troubles with talk between doctors and patients. Indiana University Press.

White, M. C., & Reavis, C. A. (1981). An analysis of Principal-Teacher communication patterns under conditions of high covert and low covert perceptual disagreement. Journal of Experimental Education, 50, 105–110.

Widdowson, H. G. (2004). Text, Context, Pretext: Critical Issues in Discourse Analysis. Blackwell Publishing.

Wood, A., & Niedenthal, P. (2018). Developing a social functional account of laughter. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 12, e12383. Online Publication: https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12383

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions This study was funded by an Australia Research Council (ARC) Small Grant 1992, Ballarat University College.

Project Title: Laughter during discussions involving two people: gender, contextual and cross-cultural differences.

Amount: A$3990.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The methodology for this study was approved by the Human Experimentation Ethics Committee, Ballarat University College (formerly Ballarat College of Advanced Education; subsequently University of Ballarat and Federation University Australia) in early 1993. No formal record of the approval can be found (see appended copy of email) but a copy of the Application has been included as Supplementary Material.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study by signing a Consent Form (Appended as Word 2 document).

Consent to publish

The author affirms that human research participants provided informed consent for aggregated data to be used within the study.

Conflicts of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions