Abstract

The Hate Crime Beliefs Scale (HCBS) is an assessment of attitudes about hate crime laws, offenders, and victims. The original HCBS includes four subscales (negative beliefs, offender punishment, deterrence, and victim harm), while a shortened and modified version from the United Kingdom (UK; HCBS-UK) consists of three subscales (denial, sentencing, and compassion). We conducted a psychometric test of the HCBS in order to identify a best fitting structure with possible item reduction. A total of 463 participants completed the original HCBS, measures of social dominance orientation (SDO) and right-wing authoritarianism (RWA), and demographic questions. Factor analyses revealed good fit of the data for a Hate Crime Beliefs Scale-Short Form (HCBS-SF), largely modeled after the HCBS-UK. The three subscales were: denial (i.e., downplaying hate crime severity and low support for hate crime laws), sentencing (i.e., support for more punitive offender punishment), and compassion (i.e., understanding and concern for victims). All subscales possessed acceptable internal consistency. The denial subscale was positively associated with RWA subscale and SDO scores. The sentencing and compassion subscales were significantly negatively correlated with SDO and RWA subscale scores. Republicans held the least supportive views of hate crime laws, concern for victims, and punishment of offenders. Data underscore the importance of evaluating hate crime beliefs in public opinion and other contexts. The HCBS-SF better captures hate crime related attitudes than the previously developed longer version of the HCBS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In 2020, a total of 11,129 hate crimes were reported in the United States (U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, n.d.); however, hate crimes are frequently not reported or are categorized differently by law enforcement and as such, the actual number of hate crimes is estimated to be approximately thirty times greater (Pezzella et al., 2019). Hate or bias crimes stem from prejudice against social groups or members of social groups and result in victimization of persons or groups and/or their property (Federal Bureau of Investigation, n.d.). In addition to physical harm, hate crimes can involve intimidation and harassment (Lockwood & Cuevas, 2020). The social groups most often targeted are distinguished by race and ethnicity, gender, country of origin, religion, sexual orientation, and disability (Lockwood & Cuevas, 2020; U.S. Department of Justice, 2017). In terms of race/ethnicity, Black individuals accounted for 48.5% of total hate crime victims in 2019 (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2020). Further, nearly 17% of hate crimes were motivated by bias regarding sexual orientation in 2019 (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2020). Hate crimes related to religion, such as anti-Jewish hate crimes, increased by 54% between 2014 and 2018 and have the third highest frequency, following race and ethnicity and sexual orientation (Hodge & Boddie, 2021; U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.). Finally, transgender persons are over four times more likely to be personally victimized and over twice as likely to have their property victimized than cisgender persons (Flores et al., 2021).

Hate crime legislation was first passed by the U.S. government in 1990 (101st Congress, 1990). In subsequent years, governing bodies strengthened this legislation by increasing penalties for hate crimes (Hate Crimes Sentencing Enhancement Act, 1994) and adding protections for disability, race and ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation, which climaxed in 2009 with the landmark Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act. Some states have passed hate crimes laws to increase punishment and fill gaps in federal legislation including increased penalties for non-violent crimes that are motivated by hate (Cabeldue et al., 2018) and elevating degrees of offense when crimes are motivated by hate (e.g., misdemeanor elevated to felony, second degree murder elevated to first degree murder) (Tex. Crim. Pro. Art. § 42.014, 2005; Tex. Penal Code Ann. §12.47, 2017). Of concern, despite enhanced hate crime legislation, reported hate crimes increased in the U.S. by 13.36% between 2019 and 2020 (U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.). Further, during the COVID-19 pandemic, hate crimes against Asian Americans in the US increased by 150% (Edmondson & Tankersley, 2021). In the face of data showing increasing rates of hate crimes, debate has continued regarding the effectiveness and constitutionality of hate crime laws (Cabeldue et al., 2018).

Not only have hate crime rates risen, but US residents’ fears of experiencing hate crimes have grown by 6% in recent years (Brenan, 2021). Beyond fears about hate crimes, beliefs about hate crime laws, offenders, and victims have political bearing. For example, protection of sexual minorities as part of hate crime laws detracts from public support for their implementation (Johnson & Byers, 2003). Moreover, a series of studies (e.g., Cramer et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2013c, 2017) show the importance of attitudes about hate crimes for legal perceptions and decision making. Overall, support for hate crime legislation is associated with more punitive decisions toward offenders (Cramer et al., 2013b). For example, perceived blame toward a hate crime perpetrator (Cramer et al., 2013a) and perceived malice of a victim in a hate crime event (Cramer et al., 2013c) impact punishment decisions. Elaborating on these patterns, Cramer and colleagues (Cramer et al. 2017) assessed narrative explanations of support for hate crime penalty enhancement laws, finding negative views toward offenders yielded favorable views about the laws, whereas persons articulating basic legal explanations (e.g., “all crimes should be treated equally”) were less likely to support these laws.

Additionally, there are several related literatures that help inform our understanding of how hate crime beliefs are formed, ranging from models of prejudice, such as the dual-process model of prejudice (Duckitt, 2001), the justification-suppression model (Crandall & Eshleman, 2003, 2005) and political attitudes (Cramer et al., 2017; Malcom et al., 2022). Most recently, Malcom and colleagues (2022) examined the mediating role of prejudice against Hispanic, Asian, and Black individuals on political affiliation and support for hate crime legislation. The authors findings suggest that individuals who hold more negative views of minorities and are affiliated with more conservative political ideologies, are less likely to support hate crime legislation. As such, it appears that the main determinates relevant to hate crime beliefs are negative attitudes toward minorities and political ideologies, which will be discussed in more detail below as correlates of the HCBS.

Given the above-mentioned findings and legal relevance of hate crime-related attitudes, it stands to reason such beliefs may influence perspectives of constitutionality of hate crime laws, and ultimately impact perceptions of local and national elections where issues of hate are part of the debate. Thus, accurate measurement of assessing hate crime beliefs has implications for research, intervention development, fear reduction, and policy-making.

Measurement of hate crime beliefs

Cabeldue et al. (2018) developed the Hate Crimes Beliefs Scale (HCBS), designed to provide a comprehensive, validated measure of hate crime-related social norms. HCBS items were derived from hate crimes literature that addressed supportive and unsupportive legal, philosophical, and social arguments (e.g., Gerstenfeld, 2011; Glaser, 2005); social and criminological theories (e.g., Chockler & Halpern, 2004; Mikula, 2003); and theories involving blame attribution and prejudice (e.g., Nelson, 2006; Shaver & Drown, 1986). Cabeldue and colleagues (2018) gathered a community sample of adults who completed 50 items used to measure beliefs about hate crimes (e.g., “hate crime perpetrators cause psychological trauma to their victims”). Exploratory factor analysis resulted in ten items being dropped due to lack of factor loadings. Four factors were identified from the remaining 40 items: 1) negative beliefs (negative views related to hate-crime legislation and protection of minority groups; 27 items; α = 0.95), 2) offender punishment (belief in strict hate crime penalties; 5 items; α = 0.84), 3) deterrence (belief that hate crime legislation is effective; 3 items; α = 0.79), and 4) victim harm (belief that hate crimes cause harm to the victim; 5 items; α = 0.74). All four factors were significantly correlated. Negative beliefs were significantly negatively correlated with offender punishment, deterrence, and harm. Deterrence was significantly positively associated with offender punishment. Harm was significantly positively associated with offender punishment and deterrence.

Regarding validity, HCBS subscales were examined for associations with political orientation and several types of prejudice (i.e., racism, transphobia, sexual prejudice, and religious intolerance). The HCBS negative beliefs subscale was most robustly and positively associated with a conservative political identity and all measures of prejudice. The other three subscales displayed positive associations with a liberal political identity, and to a lesser extent, modest significant negative associations with several prejudice metrics. In terms of predictive validity, controlling for demographic factors (e.g., participant race and gender), only the negative views subscale predicted legal decision-making in a hate crime jury decision-making scenario.

Arguing that hate crime beliefs vary across nations, Bacon et al. (2021) modified the HCBS by conducting two studies in the United Kingdom (UK). HCBS-UK modifications included additional population-specific questions (e.g., questions about Muslim and Jewish, persons, as well as persons with disabilities) as well as governmental-related modifications (e.g., freedom of speech vs. First Amendment of the US Constitution; police vs. prosecutors). These additions and modifications resulted in a pool of 46 items, which were administered in two separate studies, one study included a sample of community members and college students and the other included only community members. The four-factor model originally proposed by Cabeldue et al. (2018) did not demonstrate adequate fit among the UK sample data. Thus, Bacon et al. (2021) identified a shorter 20-item version of the HCBS-UK with three factors: 1) compassion (i.e., having understanding and concern for victims and groups affected by hate crimes; 5 items; α = 0.76), 2) denial (i.e., refusing to recognize the seriousness and extent of harm resulting from hate crimes and the need for laws to address them; 10 items; α = 0.90), and 3) sentencing (i.e., supporting punishment of those who commit hate crimes: 5 items; α = 0.89).

Sociopolitical attitudinal correlates

Sociopolitical attitudes provide an appropriate starting point for validity assessment for the HCBS. Bacon et al. (2021) examined the convergent validity of the shortened HCBS-UK. Specifically, using a community sample, they assessed the association of hate crime attitudes with measures of individual differences implicated in the formation of prejudice. Social Dominance Orientation (SDO; i.e., positive attitudes towards social inequality; Pratto et al., 1994) and Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA; i.e., authoritarian and obedience beliefs; Altemeyer, 1981) were selected by Bacon and colleagues (2021) given robust evidence of their causal role in prejudice formation and manifestation (Asbrock et al., 2010; Duckitt & Sibley, 2007, 2010; Duckitt et al., 2002; Sibley et al., 2006). The dual-process motivational model of ideology and prejudice (Duckitt, 2001) represents SDO and RWA as ideological attitudes that develop from two separate sets of personality traits, social beliefs, and social environments (Duckitt & Sibley, 2010). SDO is proposed to be formed by competitive worldviews that develop from a tough-minded personality and social contexts characterized by ingroup dominance and superiority (Duckitt & Sibley, 2009, 2010; Sibley & Duckitt, 2013). On the other hand, RWA is proposed to be formed by maladaptive worldviews that develop from high conscientiousness and threatening and unpredictable social contexts (Duckitt & Sibley, 2009, 2010). RWA is characterized by values of social conformity and security (e.g., social conservativism, traditionalism) rather than autonomy (e.g., individualism, openness; Duckitt et al., 2002). Sibley et al. (2006) discuss that levels of RWA are predictive of several types of oppressive attitudes (e.g., homophobia, religious ethnocentrism, benevolent sexism). Thus, Bacon et al. (2021) theorized that the dual-process model of prejudice may translate to hate crime beliefs and found support for this hypothesis. Bacon and colleagues found that RWA and SDO were positively correlated with the denial factor and negatively correlated with the compassion factor. Lastly, SDO was shown to be negatively correlated with the sentencing factor.

Political orientation is another factor warranting attention with the HCBS for several reasons. First, SDO and RWA are associated with political orientation (e.g., Pratto et al., 1994; Van Hiel & Mervielde, 2002). Specifically, SDO and RWA are positively correlated with right-wing party affiliation and conservative attitudes (Balliet et al., 2018; Duckitt & Sibley, 2009; Grina et al., 2016; McCann, 2009; Sidanius et al., 1994). Interestingly, data suggests that higher RWA and SDO have been strongly related to preferences for Republicans and far-right, and less favorable views of Democratic, presidential election candidates (Godbole et al., 2022; Jost et al., 2009; Van Assche et al., 2019). Second, a study examining the link between political orientation and support for hate crime law penalty enhancements highlight the importance of beliefs about hate crimes. Cramer and colleagues (2017) found that political conservatism was associated with less support for punishment aspects of hate crime laws. Further, the link between political conservatism and lack of hate crime law support was explained by narrative legal arguments such as hate crimes being treated as all other crimes. On the contrary, the link between liberal political orientation and support for hate crime laws was explained by narrative offender-focused arguments such as dehumanizing offenders. This body of evidence suggests hate crime related attitudes are politically and legally relevant, and that political identity may be linked to HCBS subscales.

The current study

Further assessment and refinement of the HCBS holds potential to impact research through public opinion and social norms/attitudes assessment. Identification of a reliable and valid measure of hate crime beliefs across countries holds potential to impact policy-making and intervention development. As such, the current study sought to examine the multi-factorial structure of the original HCBS (Cabeldue et al., 2018) in comparison to the multi-factorial structure of the shortened HCBS-UK (Bacon et al., 2021) among a community and college sample of US adults. We hypothesized:

-

H1: HCBS subscales would be significantly associated with RWA and SDO in directions consistent with prior literature. That is, RWA and SDO would be positively associated with more pejorative/less supportive subscales, and negatively associated with supportive views of issues like support for hate crime laws or victims.

-

H2: HCBS subscales would be significantly associated with political party affiliation. Republican party affiliation (compared to Democratic or other party affiliation) would be positively associated with more pejorative/less supportive subscales, and negatively associated with supportive views of issues like support for hate crime laws or victims.

We also explored the following research question:

-

RQ: Does the original factor structure of the HCBS remain more psychometrically sound compared to the shortened version of the HCBS?

Materials and method

Participants

Participants (N = 463) were primarily female (n = 340, 73.4%) and non-Hispanic White race/ethnicity (n = 401, 86.6%), with an average age of 25.55 years (SD = 10.99; see Table 1 for summary of sample demographics). Most participants had a high school education or less (n = 294, 63.6%) and were heterosexual (n = 409, 88.5%). Most participants reported a political affiliation of Republican (n = 139, 30.2%) or Democrat (n = 148, 32.1%). Most participants were of Christian faith, either Protestant (n = 222, 48.3%) or Catholic (n = 96, 20.8%). Finally, participants were primarily from the upper Midwest region of the United States (n = 342, 73.86%).

Measures

Demographics

Participants completed a demographic questionnaire assessing gender, race/ethnicity, education, political affiliation, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, and age.

Hate crime beliefs scale

The Hate Crime beliefs Scale (HCBS; Cabeldue et al., 2018) is a forty-item self-report questionnaire used to assess attitudes towards both victims and perpetrators of hate crimes, as well as hate crime legislation. Sample items include “I believe hate crimes receive too much attention” and “Hate-crime perpetrators cause psychological trauma to their victims.” Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Initial scale development yielded a four-factor structure of 1) Negative Beliefs (27 items; α = 0.95), 2) Offender Punishment (5 items; α = 0.84), 3) Deterrence (3 items; α = 0.79), and 4) Victim Harm (5 items; α = 0.74). Importantly, the present study used the original 40-item HCBS (Cabeldue et al., 2018), which does not include UK-specific items added by Bacon et al. (2021) regarding Muslim hate crimes. Further, language in the original HCBS referenced African Americans, whereas Bacon et al. (2021) use the term “Black.”

Social dominance orientation scale

The Social Dominance Orientation Scale (SDO; Pratto et al., 1994) is a 16-item self-report questionnaire used to assess one’s attitudes towards social inequality (e.g., “Some groups of people are simply inferior to other groups”, α = 0.91). Responses are indicated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Mean scores are generated via an average of the summed score, with a total possible score ranging from 1 to 7. Higher mean scores indicate greater positive attitudes towards, or preference for, social inequality and group-based dominance beliefs. Internal consistency in the current study was excellent (α = 0.90).

Right wing authoritarianism scale

Participants completed the 14-item version of the Right-Wing Authoritarianism Scale (RWA; Manganelli Rattazzi et al., 2007). The RWA assesses two sub-components: 1) submission and authoritarian aggression (e.g., “Obedience and respect for authority are the most important values children should learn”, α = 0.72) and 2) conservatism (e.g., “It is good that nowadays young people have greater freedom ‘to make their own rules’ and to protest against things they don’t like”, α = 0.75). Responses are indicated on a 7-point scale ranging from -3 (totally disagree) to +3 (totally agree). Items on the conservatism subscale are reverse scored before generating mean subscale scores. Internal consistency in the current study was acceptable for both subscales (submission and authoritarian aggression: α = 0.91; conservatism: α = 0.82).

Procedure

Participants were recruited using two sampling strategies: 1) online snowball sampling via social media platforms (i.e., Facebook and Twitter) and 2) from a student participant pool from a mid-sized Midwestern University (Brickman Bhutta, 2012). Most participants were recruited via the student research pool (n = 332, 71.7%). Interested participants were provided a link to complete the online survey battery via Qualtrics. All participants were provided an online consent form and indicated consent by clicking through to the survey. Along with the study materials, participants were presented with four attention check items to ensure mindful participation. The complete survey battery took approximately 40 to 50 min to complete. Non-student participants were not compensated for their participation, while students were incentivized with one research credit towards their course requirements. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at [University of North Dakota].

Data analysis

A total of 637 persons started the survey (i.e., clicked the link to initiate data collection). 174 were dropped due to failed attention check items or not providing any data, resulting in a final sample of 463. Data missingness on survey items for the analyzable sample ranged from 0.0% to 0.1%. Multiple imputation (Enders, 2017) was used to supplant missing values on variables of interest. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using AMOS v. 24 to compare the original four-factor (Cabeldue et al., 2018) and approximated UK three-factor (Bacon et al., 2021) models of the HCBS. Not all item wording is identical in the UK three-factor model, requiring minor adjustments to the model. HCBS subscales were permitted to correlate consistent with previous HCBS studies (Bacon et al., 2021; Cabeldue et al., 2018). Maximum likelihood estimation was used as the data were normally distributed. Our sample size of 463 satisfied statistical power requirements for both models and items per factor (Wolf et al., 2013). Acceptable model fit was determined through inspection of the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Root Mean Square Residual (RMR). The following guidelines for acceptable model fit were used: CFI > 0.90; TLI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.08, and SRMR < 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Schumaker & Lomax, 2010). We followed recommendations in the statistical literature regarding use of modification indices (e.g., Bentler, 2007, 2010). First, we decided to use post-hoc modifications because they can aid in identifying gaps or limitations of models, especially those needing development and validation. Second, we adopted a conservative cut-off (MI ≥ 25) in order to avoid model misspecification. Third, we made modifications only supported by theory or empirical literature suggesting item content was conceptually related for any error terms allowed to correlate. For example, error terms for HCBS items 36 and 37 were allowed to correlate (see details in results section) because they both pertain to the documented harm done based on anti-religious prejudice (e.g., Nadal et al., 2010). Finally, we reported model fit statistics with and without modifications, as well as the specific details regarding modifications made.

To examine hypotheses, bivariate correlations were used to assess HCBS subscales with RWA and SDO. Analysis of Variance with Bonferroni post-hoc tests and partial eta-squared effect size were used to test political affiliation differences in HCBS subscales. Political affiliation was recoded to ensure large enough sample sizes as follows: Democrat (n = 139; 32%), Republican (n = 148; 30%), and another political affiliation (n = 176; 38%).

Results

RQ1: HCBS factor structure

Model 1 was the HCBS with original four-factor structure (Cabeldue et al., 2018), allowing the following latent factors to correlate: 1) Negative Beliefs and Offender Punishment, 2) Offender Punishment & Deterrence, 3) Deterrence & Victim Harm, and 4) Offender Punishment and Victim Harm. Model 1 indicated poor model fit, (see Table 2 for model fit statistics). Model 2 retained the model 1 structure with post-hoc modifications whereby the following error terms for item pairs were allowed to correlate: negative beliefs subscale item pairs 1 & 2, 2 & 3, 1 & 3, 4 & 1, 4 & 2, 4 & 3, 7 & 8, 10 & 12, 4 & 13, 10 & 13, 12 & 13, 1 & 19, 18 & 19, 20 & 21, 20 & 23, 21 & 23, 24 & 25, 24 & 27, 25 & 27, and 26 & 27; victim harm items 36 & 37, and subscale latent variables of negative beliefs and victim harm. Model 2 indicated poor fit (see Table 2).

Model 3 was the HCBS with the UK three-factor structure, allowing the latent factors of compassion, denial, and sentencing to correlate. Model 3 indicated borderline model fit (see Table 2). Thus, model 4 allowed for implementation of post-hoc modification indices whereby error terms for item pairs were allowed to correlate as follows: items 33 & 35 and items 21 & 23 on the compassion subscale; items 1 & 2, items 1 & 19, items 2 & 19, items 6 & 19 on the denial subscale. Model 4 indicated good fit to the data (see Table 2). Factor loading values ranged from 0.357 to 0.869 in the three-factor HCBS-UK model (all ps < 0.001; see Table 3). Internal consistency values for the subscales were acceptable: denial (α = 0.94), sentencing (α = 0.80), and compassion (α = 0.73). A visual depiction of the HCBS-UK model can be seen in Fig. 1. We used this model for further hypothesis testing.

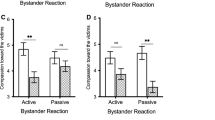

H1 and H2: Correlations with SDO and RWA

Consistent with expectations, the denial subscale score was significantly negatively associated with both the sentencing (r = -0.59, p < 0.001) and compassion (r = -0.68, p < 0.001) subscale scores, while the sentencing subscale score was significantly positively associated with the compassion subscale score (r = 0.65, p < 0.001). In support of hypotheses, the denial subscale was significantly positively associated with SDO (r = 0.65, p < 0.001) and RWA subscales (authoritarian aggression and submission: r = 0.65, p < 0.001; conservatism: r = 0.58, p < 0.001). Further supporting H1, both the sentencing and compassion subscales were significantly negatively correlated with SDO (sentencing: r = -0.40, p < 0.001; compassion: r = -0.54, p < 0.001) and the RWA subscale scores authoritarian aggression and submission (sentencing: r = -0.40, p < 0.001); compassion: r = -0.50, p < 0.001) and conservatism (sentencing: r = -0.43, p < 0.001; compassion: r = -0.51, p < 0.001).

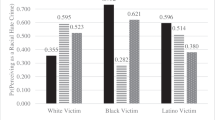

Table 4 contains HCBS subscale scores by political party. Supporting H2, Republicans indicated significantly higher denial and significantly lower sentencing and compassion beliefs compared to both Democrats and individuals of another political affiliation. Democrats indicated significantly lower denial beliefs and significantly higher sentencing and compassion beliefs compared to both Republicans and individuals of another political affiliation.

Discussion

The current study examined the multi-factorial structure of the original HCBS (Cabeldue et al., 2018) in comparison to the multi-factorial structure of the shortened HCBS-UK (Bacon et al., 2021) among a community and college sample of US adults. The original four-factor structure of the HCBS demonstrated poor fit to the data. Lack of confirmatory analytic fit for the EFA-derived Cabeldue et al. HCBS factor structure may have resulted from several reasons. First, the nature of beliefs about hate crimes may have shifted in recent years in light of documented rises in hate crimes (e.g., Hodwitz & Massingale, 2021) and socio-political attention to racial injustice (e.g., Reny & Newman, 2021). Alternatively, the complexity of the original model reported by Cabeldue and colleagues (2018) may not hold; that is, the nature of beliefs about hate crimes may be simpler than originally conceived.

On the other hand, the three-factor model demonstrated good fit to the data. Shortened and refined HCBS among a U.S. sample offers further evidence for the possibility that hate crime-related attitudes cut across country borders. Importantly, our pool of items differed from the pool of items administered via the HCBS-UK (Bacon et al., 2021) which was adapted to include items pertinent to the UK population (e.g., focus on hate crimes towards Muslims). Moving forward, we propose a shortened 17-item version of the original HCBS with three factors consistent with the HCBS-UK: 1) denial, 2) sentencing, and 3) compassion. Appendix contains the Hate Crimes Beliefs Scale-Short Form (HCBS-SF). The first factor, denial, contains eight items reflecting an attitude which downplays the impact and nefariousness of hate crimes; this factor exclusively contains items from the negative beliefs subscale of the original HCBS. The second factor, sentencing, reflects one’s support for enhanced legal punishment of those who commit hate crimes. The third factor, compassion, contains six items which reflect greater caring for victims and desire to prevent hate crime victimization. We recommend adopting Bacon et al. (2021)’s language of Black in place of African American to allow for use beyond the United States and more generally we suggest thoughtful adaptations for stigmatized groups when the measure is adopted in other countries.

The initial adaptation of the HCBS-SF provides a reliable and efficient method to capturing attitudes about hate crimes. Such attitudes are particularly salient in light of documented increases of hateful acts (e.g., Hanes & Machin, 2014), especially toward certain minority groups in the COVID-19 era (e.g., Gray & Hansen, 2021). Possible next uses of the HCBS-SF include the following. Federal and non-profit programs exist that provide hate crime training for collegiate, law enforcement, and other persons interfacing with hate crime offenders and victims (e.g., Matthew Shepard Foundation, n.d.; U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.). To the extent training content is aligned with HCBS-SF subscales, our measure can be employed during pre-training attitude assessment and as a metric of program effectiveness. Also, there is a need to determine the extent to which attitudes about hate crimes may impact relevant behaviors. As such, the HCBS-SF may be implemented in a variety of social-cognitive and behavioral contexts such as voting choices, legal decision-making, and commission of hate-motivated behavior. To the degree hate crime-related attitudes affect these outcomes, hate crime attitudes may become a target of political campaigns, jury consulting, or offender rehabilitation efforts.

Our first hypothesis was supported in that the three HCBS factors were significantly related to SDO and RWA in the predicted direction. This replicates the findings of Bacon et al. (2021), except they did not find a significant relationship between RWA and the sentencing factor, while our results revealed a significant negative relationship. The current results also extend the construct validity of the HCBS first demonstrated by Cabeldue et al. (2018) through its relationship with various measures of prejudice. Patterns associated with RWA and SDO have been demonstrated in both student samples (e.g., Duckitt & Sibley, 2007; Duckitt et al., 2002; Thomsen et al., 2008) and community samples (e.g., Sibley & Duckitt, 2013; Sibley et al., 2006). Overall, the HCBS-SF operates as expected in terms of the relationship to measures for authoritarianism and social dominance, pointing to both the political/legal relevance of the dual process model of prejudice and need to continue validity studies of the HCBS regarding factors such as political and prejudiced behavior.

The second hypothesis was supported in that HCBS-SF subscale scores were in line with politically conservative versus liberal party affiliation. Our findings provide a quantitative extension of Cramer and colleagues (2017), who reported qualitative findings about hate crime related attitudes. Political conservatism was particularly linked to legal arguments against hate crime laws, whereas political liberalism was connected to negative views of hate crime perpetrators. We replicated these patterns with regard to the denial and sentencing subscales, respectively. The compassion subscale adds a further domain warranting examination in political and legal decision-making contexts in future research.

Overall, these findings are further support for the data presented by Malcom and colleagues (2022) that highlight the importance of prejudice, political affiliation, and attitudes on hate crime beliefs. The dual process model of prejudice formation (Gerstenfeld 2011) appears to continue informing our understanding of hate crime beliefs. Based on our data, some practical implications would be to consider the attitudes and political beliefs of individuals who draft hate crime related legislation. Inevitably, it will be important to have a diverse group of individuals working together to determine appropriate hate crime laws and legislation.

Our findings should be considered in the context of study limitations. To begin, the convenience sampling strategy limited generalizability. Although both students and community-dwelling adults were sampled to remain consistent with Bacon and colleagues (2021), our sample was quite limited with regard to geographic U.S. region, gender, and race/ethnicity. In light of the diverse array of victimization categories (e.g., by race, sexual orientation, disability status), future research should use the HCBS-SF with demographically diverse groups. Second, while we demonstrated convergent validity with cognitive measures related to socio-political attitudes, we did not examine how hate crime beliefs were related to either enacted hate crime violence or victimization history. Future research should examine how hate crime beliefs may differ among (1) those with and without a history of hate crime victimization and (2) those with and without a history of hate crime perpetration. Statistically, we employed modification indices in order to identify possible points of refinement in identifying the ideal HCBS factor structure. Use of MIs in measure development is debated (Bentler, 2010). In line with recommendations in the literature (e.g., Bentler, 2007) we recommend validation of the final HCBS model in additional samples in order to ensure the generalization of the reduced three-factor structure. Finally, future psychometric work is needed examining the factor structure of the shortened version of the HCBS with more diverse samples, including samples with more men and of older age. The demographics of the current sample differed from the demographics of typical hate crime perpetrators, representing a needed area for future research. Hate crime perpetrators are majority White (55.1%) and primarily male (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism [START], 2020); U.S. Department of Justice, n.d.). Future studies with more diverse, larger samples would also allow for examination of measurement invariance across demographic groups, such as gender, race, religion, and sexual orientation.

References

Altemeyer, B. (1981). Right-wing authoritarianism. University of Manitoba Press.

Asbrock, F., Sibley, C. G., & Duckitt, J. (2010). Right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation and the dimensions of generalized prejudice: A longitudinal test. European Journal of Personality, 24(4), 324–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.746

Bacon, A. M., May, J., & Charlesford, J. J. (2021). Understanding public attitudes to hate: Developing and testing a UK version of the Hate Crime Beliefs Scale. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(23–24), NP13365-NP13390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520906188.

Balliet, D., Tybur, J. M., Wu, J., Antonellis, C., & Van Lange, P. A. (2018). Political ideology, trust, and cooperation: In-group favoritism among Republicans and Democrats during a US national election. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62(4), 797–818. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002716658694

Bentler, P. M. (2007). On tests and indices for evaluating structural models. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 825–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.024

Bentler, P. M. (2010). SEM with simplicity and accuracy. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20, 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2010.03.002

Brenan, M. (2021). Crime fears rebound in U.S. after lull during 2020 lockdowns. Gallup News. https://news.gallup.com/poll/357116/crime-fears-rebound-lull-during-2020-lockdowns.aspx

Brickman Bhutta, C. (2012). Not by the book: Facebook as a sampling frame. Sociological Methods & Research, 41(1), 57–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124112440795

Cabeldue, M. K., Cramer, R. J., Kehn, A., Crosby, J. W., & Anastasi, J. S. (2018). Measuring attitudes about hate: Development of the hate crime beliefs scale. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(23), 3656–3685. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516636391

Chockler, H., & Halpern, J. Y. (2004). Responsibility and blame: A structural model approach. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 22, 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1613/jair.1391

Cramer, R. J., Gorter, E. L., Rodriguez, M. D. C., Clark, J. W., Rice, A. K., & Nobles, M. R. (2013a). Blame attribution in court: Conceptualization and measurement of perpetrator blame. Victims & Offenders, 8(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2012.745458

Cramer, R. J., Kehn, A., Pennington, C. R., Wechsler, H. J., Clark, J. W., III., & Nagle, J. (2013b). An examination of sexual orientation-and transgender-based hate crimes in the post-Matthew Shepard era. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 19(3), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031404

Cramer, R. J., Nobles, M. R., Amacker, A. M., & Dovoedo, L. (2013c). Defining and evaluating perceptions of victim blame in antigay hate crimes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28, 2894–2914. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513488687

Cramer, R. J., Laxton, K. L., Chandler, J. F., Kehn, A., Bate, B. P., & Clark, J. W. (2017). Political identity, type of victim, and hate crime-related beliefs as predictors of views concerning hate crime penalty enhancement laws. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 17(1), 262–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12140

Crandall, C. S., & Eshleman, A. (2005). The justification-suppression model of prejudice: An approach to the history of prejudice research. In Social psychology of prejudice: historical and contemporary issues/edited by Christian S. Crandall, Mark Schaller. Lawrence, Kan.: Lewinian Press, 2005. Lawrence, Kan.: Lewinian Press.

Crandall, C. S., & Eshleman, A. (2003). A justification-suppression model of the expression and experience of prejudice. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 414–446. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.414

Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2007). Right wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and the dimensions of generalized prejudice. European Journal of Personality: Published for the European Association of Personality Psychology, 21(2), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.614

Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2009). A dual-process motivational model of ideology, politics, and prejudice. Psychological Inquiry, 20(2–3), 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400903028540

Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2010). Personality, ideology, prejudice, and politics: A dual-process motivational model. Journal of Personality, 78(6), 1861–1894. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00672.x

Duckitt, J., Wagner, C., du Plessis, I., & Birum, I. (2002). The psychological bases of ideology and prejudice: Testing a dual process model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.1.75

Duckitt, J. (2001). A dual process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 33, pp. 41–1 13). Academic Press.

Edmondson, G. & Tankersley, J. (2021). Biden signs bill on hate crimes against Asian-Americans. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/20/us/politics/biden-asian-hate-crimes-bill.html

Enders, C. K. (2017). Multiple imputation as a flexible tool for missing data handling in clinical research. Behavior Research and Therapy, 98, 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.008

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2020). Uniform Crime Report: Hate Crime Statistics, 2019. U.S. Department of Justice. https://ucr.fbi.gov/hate-crime/2019/topic-pages/victims.pdf

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (n.d.). What we investigate: Hate crimes. www.fbi.gov/investigate/civil-rights/hate-crimes

Flores, A. R., Meyer, I. H., Langton, L., & Herman, J. L. (2021). Gender identity disparities in criminal victimization: National crime victimization survey, 2017–2018. American Journal of Public Health, 111(4), 726–729. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.306099

Gerstenfeld, P. B. (2011). Hate crimes: Causes, controls, and controversies. SAGE Publications.

Glaser, J. (2005). Intergroup bias and inequity: Legitimizing beliefs and policy attitudes. Social Justice Research, 18, 257–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-005-6825-1

Godbole, M. A., Flores-Robles, G., Malvar, N. A., & Valian, V. V. (2022). Who do you like? Who will you vote for? Political ideology and person perception in the 2020 US presidential election. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 22(1), 30–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12292

Gray, C., & Hansen, K. (2021). Did COVID-19 lead to an increase in hate crimes toward Chinese people in London? Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 37(4), 569–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/10439862211027994

Grina, J., Bergh, R., Akrami, N., & Sidanius, J. (2016). Political orientation and dominance: Are people on the political right more dominant? Personality and Individual Differences, 94, 113–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.01.015

Hanes, E., & Machin, S. (2014). Hate crime in the wake of terror attacks: Evidence from 7/7 and 9/11. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 30(3), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986214536665

Hate Crimes Prevention Act (2009). Public Law Number 111–84.

Hate Crimes Sentencing Enhancement Act (1994). 28 U.S.C. 994.

Hodge, D. R., & Boddie, S. C. (2021). Anti-Semitism in the United States: An overview and strategies to create a more socially just society. Social Work, 66(2), 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swab011

Hodwitz, O., & Massingale, K. (2021). Rhetoric and hate crimes: Examining public response to the Trump narrative. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2021.1936121

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Johnson, S. D., & Byers, B. D. (2003). Attitudes toward hate crime laws. Journal of Criminal Justice, 31, 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2352(03)00004-7

Jost, J. T., West, T. V., & Gosling, S. D. (2009). Personality and ideology as determinants of candidate preferences and “Obama conversion” in the 2008 US presidential election. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 6(1), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X09090109

Lockwood, S., & Cuevas, C. A. (2020). Hate crimes and race-based trauma on Latinx populations: A critical review of the current research. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 1–27,. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020979688

Malcom, Z. T., Wenger, M. R., & Lantz, B. (2022). Politics or prejudice? Separating the influence of political affiliation and prejudicial attitudes in determining support for hate crime law. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000350

Manganelli Rattazzi, A. M., Bobbio, A., & Canova, L. (2007). A short version of the right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(5), 1223–1234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.03.013

Matthew Shepard Foundation. (n.d.). Creating safer communities: hate crime prevention training. https://www.matthewshepard.org/creating-safer-communities-hate-crimes-prevention-training/

McCann, S. J. (2009). Authoritarianism, conservatism, racial diversity threat, and the state distribution of hate groups. The Journal of Psychology, 144(1), 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980903356065

Mikula, G. (2003). Testing an attribution-of-blame model of judgments of injustice. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 798–811. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.184

Nadal, K. L., Issa, M.-A., Griffin, K. E., Hamit, S., & Lyons, O. B. (2010). Religious microaggressions in the United States: Mental health implications for religious minority groups. In D. W. Sue (Ed.), Microaggressions and marginality: Manifestation, dynamics, and impact (pp. 287–310). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. (2020). National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism research brief: Motivations and characteristics of hate crime offenders. https://start.umd.edu/pubs/START_BIAS_MotivationsCharacteristicsOfHateCrimeOffenders_Oct2020.pdf

Nelson, T. D. (2006). The psychology of prejudice (2nd ed.). Pearson Education.

Pezzella, F. S., Fetzer, M. D., & Keller, T. (2019). The dark figure of hate crime underreporting. American Behavioral Scientist. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218823844

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741–763. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741

Reny, T. T., & Newman, B. J. (2021). The opinion-mobilizing effect of social protest against police violence: Evidence from the 2020 George Floyd protests. American Political Science Review, 115(4), 1499–1507. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000460

Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2010). A beginner's guide to structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Shaver, K. G., & Drown, D. (1986). On causality, responsibility, and self-blame: A theoretical note. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 697–702. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.4.697

Sibley, C. G., & Duckitt, J. (2013). The dual process model of ideology and prejudice: A longitudinal test during a global recession. The Journal of Social Psychology, 153(4), 448–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2012.757544

Sibley, C. G., Robertson, A., & Wilson, M. S. (2006). Social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism: Additive and interactive effects. Political Psychology, 27(5), 755–768. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00531.x

Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., & Bobo, L. (1994). Social dominance orientation and the political psychology of gender: A case of invariance? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 998–1011. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.998

101st Congress (1990). H.R. 1048 – hate crime statistics act [Statute]. https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/house-bill/1048/text

Texas Criminal Procured Article. § 42.014. (2005). https://law.justia.com/codes/texas/2005/cr/001.00.000042.00.html

Texas Penal Code Ann. § 12.47. (2017). https://law.justia.com/codes/texas/2017/penal-code/title-3/chapter-12/

Thomsen, L., Green, E. G., & Sidanius, J. (2008). We will hunt them down: How social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism fuel ethnic persecution of immigrants in fundamentally different ways. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(6), 1455–1464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.06.011

U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2017). Crime in the United States, 2017. https://ucr.fbi.gov/hate-crime

U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation. (n.d.). 2020 Hate Crime Statistics. https://www.justice.gov/hatecrimes/hate-crime-statistics

U.S. Department of Justice. (no date). National hate crimes training curriculum. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/186784.pdf

Van Hiel, A., & Mervielde, I. (2002). Explaining conservative beliefs and political preferences: A comparison of social dominance orientation and authoritarianism. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(5), 965–976. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00250.x

Van Assche, J., Dhont, K., & Pettigrew, T. F. (2019). The social-psychological bases of far-right support in Europe and the United States. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 29(5), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2407

Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., & Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 76(6), 913–934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164413495237

Funding

This work was supported by the Joyce and Aqueil Ahmad Endowment at the University of North Dakota awarded to the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Authors declare no conflicts.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Hate crime beliefs scale (HCBS) – short form

Instructions: Please rate the statements below using the following 5-point scale.

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree |

____1. I believe hate crimes receive too much attention.

____2. Hate crime victims receive too much attention.

____3. Prosecutors spend too much time pursuing hate crimes.

____4. The media makes hate crimes into a bigger deal than they actually are.

____5. Hate crime law protection of Black people is unnecessary.

____6. Crimes against transgender people receive too much attention in the news.

____7. Charging someone with a separate hate crime charge is excessive prosecution.

____8. Having to report crimes against transgender people is unnecessary.

____9. Evidence of bias motivation in a crime should be an aggravating factor in sentencing.

____10. A hate crime offender should receive a lengthier prison sentence.

____11. Offenders who target Black people based on their race deserve a longer prison sentence.

____12. Hate crime perpetrators cause psychological trauma to their victims.

____13. Sexual orientation bias-motivated crimes are threatening to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender community at large.

____14. Crimes against people that are physically impaired are threatening to the entire community of people with disabilities.

____15. Harsh punishments of hate crime offenders will decrease the likelihood of future hate crimes.

____16. Legislation including people with disabilities will discourage crimes against this group of people.

____17. Crimes against Black people are threatening to racial minorities at large.

Scoring:

Denial: Sum 1–8

Sentencing: Sum 9–11

Compassion: Sum 12–17

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kehn, A., Kaniuka, A.R., Benson, K. et al. Assessing attitudes about hate: Further validation of the hate crime beliefs scale. Curr Psychol 42, 25017–25027 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03626-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03626-6