Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has radically altered everyday interactions, potentially disrupting the process of romantic relationship formation. Prior research suggests that threats to the basic psychological need for relatedness, along with negative mental imagery, can lead to an obsessive preoccupation with a romantic interest. The present research examines how the relatedness-threatening nature of the pandemic may similarly facilitate problematic relationship behaviors. Two studies—a small-scale natural experiment with measurements before and during the pandemic (Study 1) and a daily diary study (Study 2)—investigated how relatedness frustration and negative fantasies predict presumptuous romantic intentions. In Study 1 these threats unexpectedly corresponded to reduced presumptuous romantic intentions, though no such main effect was present in Study 2. Replicating prior experimental work, in both studies, more negative fantasies about a romantic target predicted greater presumptuous romantic intentions. Study 2 also revealed that at the between-person level the combinatory effect of relatedness frustration and negative fantasies led to greater intentions. At the within-person level, this combinatory effect led unexpectedly to reduced intentions. Finally, there was substantial heterogeneity in the within-person effect of COVID-induced relatedness frustration: although frustration stoked intentions for some individuals, for others it reduced intentions. This work suggests that for many, the early social ramifications of COVID-19 reduced motivation to presumptuously pursue romantic relationships. Yet, certain individuals, particularly those with more negative fantasies, are more prone to pursue presumptuously amidst the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The widespread implementation of social distancing measures designed to manage the COVID-19 pandemic has radically changed the nature of everyday interactions. These measures may be especially disruptive when it comes to personal relationships (Pietromonaco & Overall, 2020), including the formation of new romantic bonds. More than ever, it is important for behavioral researchers to understand how challenges to making connections with others—like the current global pandemic—influence romantic relationship pursuit and maintenance. This is especially important given the central role close relationships play in overall well-being and health (Knee et al., 2013).

The ways in which individuals seek out and foster romantic connections can come to bear heavily on a relationship’s success. Indeed, when individuals are overly persistent in their attempts to court a romantic interest (e.g., Cupach et al., 2011), relationship success is unlikely and, when unwanted by the recipient, can even qualify as stalking behavior (Sinclair & Frieze, 2005). Moreover, the social consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic may intersect with and amplify these perennial relationship pursuit challenges, leading individuals—especially those in the earlier phases of a romantic relationship—to engage in problematic relationship behaviors.

Research by Valshtein and colleagues (2020) offers one explanation for how COVID-19 may influence individuals’ propensity to engage in such problematic behaviors. They found that experimentally induced threats to participants’ feelings of connectedness increased their in-the-moment obsessive thinking about a romantic partner (e.g., feeling overcome by thoughts and images about the partner). Greater obsessive thinking, in turn, was associated with greater endorsement of intentions to engage in stalking-like behaviors (e.g., showing up to the partner’s home unannounced, sending them desperate messages). Some participants in these studies were experimentally directed to engage in fantasies of how interacting with their partner could go wrong. These negatively-valenced fantasies led to greater obsessive thinking. In other words, more problematic patterns of thought and behavioral intentions were observed in those made to feel socially disconnected, and in those with negative interpersonal fantasies. With social distancing practices as a widespread, naturally occurring threat to social connection, we are interested in whether the findings of Valshtein et al. (2020) apply in the context of early-stage romantic relationships during COVID-19. That is, whether the combinatory effect of COVID-induced threats to relatedness, and negative fantasies predict greater intentions to presumptuously pursue a romantic interest.

Romantic pursuit during COVID-19

Research on how the COVID-19 pandemic affects romantic relationships—especially those of highly committed, cohabiting couples—is rapidly accumulating (e.g., Balzarini et al., 2020; Williamson, 2020). However, many American adults are either single or in non-cohabiting romantic relationships (Thornton & Young-DeMarco, 2001). COVID-19-related social mitigation practices including partial lockdown, mass gathering restrictions, and social distancing measures present unique challenges for this population that may restrict opportunities for building romantic bonds. Despite these hurdles, many individuals remain actively engaged in romantic pursuit, often aided by technology-facilitated interactions (Lehmiller et al., 2020).

It is especially important to understand how COVID-19 has influenced intentions to engage in presumptuous behaviors among people in the early phases of a romantic relationship. In line with work on goal intentions (Gollwitzer & Moskowitz, 1996), presumptuous romantic intentions can be defined as the strategies an individual plans to enact that are thought (by the pursuer) to effectively maintain and enhance emotional, cognitive, and physical closeness to a romantic interest—irrespective of if the person being pursued is a current, former, or prospective romantic partner, and regardless of if these courtship behaviors are reciprocated. For example, a pursuer may intend to go through a romantic interest’s private things, send them explicit messages, or surprise them with an unannounced visit (Valshtein et al., 2022). Even if use of these tactics does not reach the criteria for criminal stalking or the intent is benign, such behaviors may be undesired by the recipient and, as such, counterproductive to relationship formation.

COVID-19 social mitigation measures as a relatedness need threat

As others have suggested (Matias and Marks, 2020), the COVID-19 pandemic represents a severe challenge to psychological homeostasis and may be especially threatening to individuals’ need for relatedness. The need for relatedness is the universal requirement to experience warm, caring interactions and bonds with others; fulfilling this need is essential to well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2017; Vansteenkiste et al., 2020). By vastly restricting ordinary means of social interaction, COVID-19 poses a direct threat to relatedness (Simard & Volicer, 2020): it may not only deprive people of opportunities to satisfy their need for relatedness, but it may also actively thwart relatedness via isolation and disconnection (see Chen et al., 2015).

Threats to basic psychological needs, as the COVID-19 context may have been, induce need arousal—that is, need threats stoke motivation to seek need satisfaction (Prentice et al., 2014). For example, participants in one study who received false feedback about ending up alone were higher in relationship-oriented motivation than participants given false feedback regarding a different psychological need (Sheldon & Gunz, 2009, Study 2). And, per an internal meta-analysis by Valshtein et al. (2020), the presence of a relatedness threat (e.g., cyberball exclusion) increased participants’ obsessive thinking, which was predictive of greater presumptuous romantic intentions. As such, people should be more motivated to seek out satisfying social interactions to the extent that COVID-19 threatens their need for relatedness.

There are, however, important considerations that cast doubt on this hypothesis. First, during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially the early stages, relatedness threats from social mitigation may have been directly tied to personal health and safety risks. Meaning, the more that COVID-related risks required physical distancing, and thus threatened relatedness needs, the more connecting with others in-person posed the threat of contracting and spreading the illness. The same conditions that promoted presumptuous romantic connection-seeking may also have dampened connection-seeking due to legitimate health concerns. Yet, pursuit behaviors that do not require close physical contact—such as “sexting” (Lehmiller et al., 2020)—would not necessarily be curtailed by worsening COVID-19 transmission.

A second consideration is that a heightened need for relatedness during the COVID-19 pandemic could be met through non-romantic close others, especially because need threat is conceptualized as applying to the general relatedness need, rather than a need to connect with a specific romantic interest. If some individuals who craved connection under pandemic conditions secured it via non-romantic relationships, a positive association between relatedness threat and presumptuous romantic intentions may not emerge, at least not on the average. However, the growing literature on relationships during COVID-19 suggests that for many individuals, romantic and sexual pursuits have persisted despite the constraints of the pandemic (e.g., Lehmiller et al., 2020) and would thus be an outlet for heightened relatedness needs.

Accordingly, our first objective (Aim 1) is to understand whether the threat to relatedness posed by COVID-19 mitigation strategies predicts differences in intentions to presumptuously pursue a romantic interest. Importantly, there are numerous ways to conceptualize how COVID-19 affects relatedness. On the one hand, COVID-19 can be construed as an objective, relatedness threat, in the sense that the ability to connect socially for many has been hampered compared to before the pandemic. But it can also be construed psychologically, in terms of the subjective experience of relatedness frustration: individuals’ perceptions of the degree of COVID-19 hampering their social connections can vary from person-to-person and from day-to-day., irrespective of the fact that the COVID-19 pandemic may be a stable relatedness threatening context. In both cases, we predict the COVID-related social restrictions will threaten and for the most part subsequently frustrate relatedness needs, thereby resulting in increased presumptuous romantic intentions.

Negative fantasies about a romantic interest

Beyond the context of COVID-19, the way someone thinks about a romantic interest may influence their relationship pursuit strategies. Doubts, obsessions, and other unpleasant thoughts, for example (Doron & Kyrios, 2005), play a role in romantic relationship dynamics. Building on Valshtein et al. (2020), of particular interest are how negative fantasies about a romantic interest function as a predictor of presumptuous romantic intentions in early-stage romantic relationships.

Negative fantasies are thoughts and mental images about future-oriented scenarios that are experienced as unpleasant—that is, negatively valenced (Oettingen, 2012; Oettingen & Mayer, 2002). For example, one could imagine going for coffee with a potential romantic partner and having an awkward, cold conversation. Such fantasies may intensify relationship pursuit. Consistent with this notion, Oettingen and Mayer (2002) found that participants with more negatively valenced fantasies about potential obstacles to relationship formation were both more actively pursued and more likely to have formed an intimate relationship, adjusting for expectations of success. Similarly, Valshtein et al. (2020) found that having negative (vs. positive) fantasies about things going poorly with a romantic partner increased obsessive thinking about them, which predicted intentions to seek closeness to that partner.

This pattern can be explained by research on the self-regulatory strategy of mental contrasting (Oettingen et al., 2001). During mental contrasting, pleasant fantasies of attaining a desired future are contrasted with negatively valenced fantasies of obstacles that might stand in the way (overview by Oettingen, 2012). Given sufficient expectations for success, mental contrasting strengthens goal commitment and increases energy to tackle challenges (Oettingen et al., 2001). From this perspective, negative fantasies about a romantic interest may make the obstacles inherent in relationship pursuit more salient and therefore strengthen pursuit intentions.

These predictions are in line with other theories of motivation. Per motivational intensity theory, negative fantasies that heighten the perceived degree of difficulty in pursuing the romantic interest should increase effort mobilization—here, stronger intentions to take a presumptuous course of action—so long as the relationship is sufficiently desirable (Sciara & Pantaleo, 2018). Moreover, the same needs-as-motives (e.g., Prentice et al., 2014) logic used in discussing COVID-induced relatedness threat can be applied here. Negative fantasies themselves may be viewed as a threat to relatedness, to the extent that these unpleasant thoughts and images of interacting with the romantic interest stir real feelings of rejection and disconnectedness. So, threatening relatedness via negative fantasies should motivate individuals to seek closeness to them.

Accordingly, we hypothesize that individuals with more negative fantasies about a romantic interest will report stronger presumptuous romantic pursuit intentions (Aim 2). In line with Oettingen and Mayer (2002), we expect this to be the case whether negative fantasies are conceptualized in terms of valence (i.e., how negative) or frequency (i.e., how often).

Interaction between COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies

One unique aspect of conducting this research during the COVID-19 pandemic is this ability to explore the interrelations between a relatedness-threatening social context (COVID-19) and individual vulnerabilities (negative fantasies; see Pietromonaco & Overall, 2020) as determinants of relationship pursuit in everyday life. In the tradition of classic social psychological theorizing of person-environment interactions, we examine whether presumptuous romantic intentions may be better predicted by an interaction between the social consequences of the COVID-19 context and individuals’ negative fantasies about their romantic interest.

An interaction pattern would be consistent with the work by Valshtein et al. (2020), who observed that in the presence of an aroused relatedness need, negative fantasies left individuals preoccupied with their unmet need, and thus more inclined to engage in behaviors to redress that unmet need. In other words, negative fantasies should be particularly motivating towards the pursuit of a romantic interest in the presence of a threat to relatedness. On the other hand, less negatively valenced fantasies could be used effectively to satisfy relatedness (Oettingen & Mayer, 2002) and ameliorate the drive to pursue. So, our third objective (Aim 3) is to test whether negative fantasies more strongly predict presumptuous romantic intentions when under greater relatedness threat posed by COVID-19. Because the threat-by-fantasy interaction pattern observed in Valshtein et al. (2020) was not conclusive, Aim 3 is considered in terms of the complexity it may add to Aims 1 and 2, rather than a primary aim.

The present research

COVID-19 was assessed as a relatedness threat (Aim 1), negative fantasies (Aim 2), and their interaction (in Study 2 only; Aim 3) as predictors of intentions to enact presumptuous behaviors to pursue a romantic interest or early-stage romantic partner, with two online longitudinal studies of U.S. university students. In Study 1, participants reported on their presumptuous romantic intentions prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. A follow-up survey was then conducted during the first wave of COVID-19 transmission in the U.S. (late April, 2020) that included a second measure of presumptuous romantic intentions, as well as measures of other variables of interest. With social mitigation regulations serving as a naturalistic relatedness threat induction across all participants, this objective conceptualization of relatedness threat was used to examine the average change in presumptuous romantic intentions from before to during the pandemic. The subjective experience of COVID-induced relatedness frustration, as well as fantasy negativity during the pandemic were also used to predict the extremity of change in intentions.

Study 2 was conducted over several weeks starting in October 2020, when the second wave of transmission was approaching its peak in the U.S. Daily self-reports of participants’ COVID-induced relatedness frustration, frequency of negative fantasies, and presumptuous romantic intentions were obtained. Although all participants were living in the context of relatedness threatening social mitigation regulations, we quantified differences in the severity of COVID-induced relatedness frustration at both the between- and within-persons levels. For example, individuals who live alone may experience greater relatedness frustration due to COVID than those who live with roommates or family (between-persons). And a given individual may experience greater relatedness frustration on a day when they see an advertisement from their state government imploring them to stay at home due to rising infection rates (within-persons). The predictions should apply on both the between- and within-person levels, but as relevant past research has only examined between-person effects, these within-person analyses are exploratory tests.

Additionally, in Study 2, the degree of heterogeneity in the effects of interest will be estimated (Aim 4) using a novel statistical approach (Bolger et al., 2019). Altogether, we aim to better understand how individuals—whose basic psychological needs may be frustrated by the pandemic and ensuing social mitigation—think about, develop, and maintain romantic connections. Note, although previous research has investigated the effects of positively-valenced mental imagery in the romantic context (Oettingen & Mayer, 2002), to more closely follow Valshtein et al. (2020), the present research will only examine negative fantasies.

Study 1

In a small-scale, natural experiment with undergraduate students we sought to conceptually replicate in-lab research (Valshtein et al., 2020). Our initial, pre-registered research plan (https://bit.ly/covid19pri-prereg) stipulated a final sample size of at least 150 participants. However, as only a much smaller sample was obtained, a simpler, modified version of those analyses was conducted. First, participants’ presumptuous romantic intentions at Time 1 should correlate with presumptuous romantic intentions at Time 2, but intentions should be higher during COVID-19 due to the relatedness threatening nature of the pandemic. We hypothesized that participants subjectively experiencing greater COVID-induced relatedness frustration would also report a greater change in presumptuous romantic intentions from before to during the pandemic (Aim 1; Sheldon & Gunz, 2009; Valshtein et al., 2020). We anticipated that participants who report more negative fantasies about a romantic interest would report greater intentions to enact presumptuous behaviors from before to during the pandemic (Aim 2). Because of the small sample size, the pre-registered interaction between COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies (Aim 3) was not examined.

Method, study 1

Participants and procedure

In Study 1, undergraduate students (n = 52) from a large private university in the U.S. were recruited to complete questionnaires at two separate time points: once in the month preceding COVID-19 related social mitigation measures (Time 1, early Feb. 2020) and another two months into the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. (Time 2, late April 2020). Both surveys were conducted online via Qualtrics, and participants were compensated with course credit.

The Time 1 survey was a multipurpose battery of questionnaires that included our measure of presumptuous romantic intentions, as well as questionnaires for unrelated studies. These unrelated measures were only used for the purpose of comparing our final sample to the pool of eligible Time 1 survey completers (see Results). Because it was not yet a public health concern in the U.S., the Time 1 survey did not contain any measures related to COVID-19. All other relevant study variables were collected during Time 2.

Any undergraduate psychology student in the department participant pool was eligible for the Time 1 survey, yielding a sample of 380 participants. From this initial recruitment, Time 2 survey data was collected amidst the height of the first wave of COVID-19 transmission, with the express purpose of understanding changes in individuals’ presumptuous romantic intentions from before to during the pandemic. Only 52 participants responded to the second survey, likely due to challenges in quickly implementing remote learning and research recruitment procedures.

The final sample comprised 14 men, 35 women, and 3 trans or gender nonbinary participants. This sample contained 7 individuals who reported being in a romantic relationship, 31 who had a romantic interest they wanted to pursue, and 12 who failed to report their relationship status. Finally, this sample was racially and ethnically heterogeneous: 44% identified as Asian, 26% identified as White, 14% identified as Multiracial or some other racial/ethnic group not listed, 10% identified as Latinx, and 6% identified as Black. Participants spent a median 57.84 min (MAD = 22.02 min) on the complete baseline survey and a median 15.73 min (MAD = 6.21 min) for the follow-up survey.

Measures

Information about romantic interest

After consenting to the Time 2 survey, participants were asked if they were currently in a romantic relationship. If they answered no, participants were then asked if they were “currently interested in or pursuing anyone sexually or romantically (e.g., a crush).” If participants again answered no, they were asked to think about someone with whom they would theoretically be interested in having a romantic relationship. Once participants responded “yes” to one of these prompts, they wrote the pertinent person’s name (e.g., if they were in a relationship, they typed in their partner’s name). This name was inserted into all subsequent questions pertaining to participants’ romantic interest (indicated below by < ROMANTIC INTEREST >). Finally, participants were whether they were currently living with the romantic interest, how often they had been in contact with them recently, and where the romantic interest was currently located.

COVID-induced relatedness frustration

Pertinent to our main hypotheses, participants reported on the subjective experience of COVID-induced relatedness frustration in the Time 2 survey. Because at the time of data collection there was no previously validated measure assessing the degree to which participants felt COVID-19 was responsible for stifling their social connections, and because expeditious data collection amidst the first wave of the pandemic was essential, a well-validated scale was adapted for use in the COVID-19 context. Because an important aspect of relatedness is feeling connected to others, participants were responded to the 4-item UCLA loneliness scale (Russell, 1996), which probed individuals’ loneliness over the past two weeks (e.g., “How often did you feel that you lacked companionship”). However, to ensure this measure of relatedness frustration tapped into COVID-19-related concerns specifically, three new items were generated to augment these loneliness items. Participants responded to how much COVID-19 was interfering with participants’ ability to make meaningful social connections (item 1), complete work, schoolwork, or other responsibilities (item 2), and how worried they were about getting or transmitting COVID-19 (item 3). Importantly, because the loneliness items and COVID-19-specific items were measured on different Likert-type scales (1 [not at all] to 6 [all of the time] and 1 [not at all] to 7 [a great deal], respectively), all seven items were centered and standardized prior to to creating a composite score. This prevented unequal weighting of unit changes across items. After dropping one item (completing work or other responsibilities), reliability was sufficient (α = 0.69) and neither removing additional items nor adding other related items such as social distancing adherence improved internal consistency.Footnote 1

To ensure that these items are a valid measure of relatedness frustration, several analyses were conducted to assess whether this measure correlated with a commonly used measure of basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration (Chen et al., 2015), which was included in the Time 2 survey. COVID-induced relatedness frustration measure correlated moderately with relatedness frustration, as expected (for detailed analyses, refer to the supplemental materials). Finally, participants reported on several additional experiences with COVID-19 (e.g., how many people they were living with; see the online supplement for full measures) that are ancillary to our primary aims and will not be discussed further.

Negative fantasies

To measure negative fantasies at Time 2, individuals responded to two items: “typically how negative are your fantasies about < ROMANTIC INTEREST > ” and “typically how unpleasant are your fantasies about < ROMANTIC INTEREST > ?” These two items were averaged together to create an indicator of negative fantasies. In addition to how negative participants’ fantasies were, they were also asked about the intensity, intrusiveness, and frequency of these fantasies. All items were assessed on a 1 to 7 scale where higher scores indicated more extremely valenced, more intense, more intrusive, and more frequent fantasies (anchors varied by item). Additionally, positive fantasies were measured in the same manner, but because our theoretical interest was in negative fantasies, they were not included in any analyses.

Presumptuous romantic intentions

Participants completed a recently validated 13-item measure of intentions to enact presumptuous romantic behaviors (Valshtein et al., 2022) in both the Time 1 and Time 2 surveys. Adapted from a checklist measuring Obsessive Relational Intrusion (Cupach & Spitzberg, 1998), this measure is based on research on victim-report of perpetrator stalking-like behavior (Spitzberg et al., 1998). This measure taps into general presumptuousness (though subscores can be calculated, if relevant) and has been shown to predict actual relationship behaviors and a variety of relationship outcomes (e.g. maintenance behaviors, commitment, narcissism, and entitlement, among others). Participants were told that “sometimes people engage in a variety of behaviors to get the attention of romantic or sexual interest or relationship partner” and then asked on a 1 (not at all likely) to 7 (extremely likely) Likert-type scale how likely they “would be to engage in the following behaviors in order to attract or maintain the interest” of a romantic interest or relationship partner. Sample items include, “surprise them by showing up unannounced” and “send desperate notes/letters/messages to them.” All 13 items were averaged, such that higher scores indicate greater presumptuous romantic intentions. The measure had satisfactory reliability at both time points (αtime1 = 0.81, αtime1 = 0.82). Note, in the Time 2 survey, the following instruction was also included: “please answer these questions with respect to how you would act, not necessarily how you are able to act in light of COVID-19 related regulations.” This additional instruction was important for the measure to capture the same underlying construct of presumptuous romantic intentions in the new context of the pandemic at Time 2.

Demographics and other variables

In addition to the primary variables of interest, the Time 2 survey assessed age, race, gender, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. Participants reported how often they had dreams during sleep and how often those dreams were about the romantic target. Participants also completed a 4-item measure of perceived stress (Cohen et al., 1983), a 4-item measure of general mental health (Kroenke et al., 2009), and a 12-item measure of perceived social support (Kazarian & McCabe, 1991). See the online supplement for more information regarding measures beyond the immediate scope of the current research.

Results, study 1

All analyses were conducted in R Version 4.0.2 (R Core Team, 2020). Because Study 1 comprised a convenience sample during the height of the pandemic’s first wave, comparisons were conducted to ensure that our final sample (n = 52) did not differ from other eligible participants in the baseline introductory psychology sample (n = 342). Those who responded to the Time 2 survey were not meaningfully different from this larger pool of participants (see https://bit.ly/sociallydistantrelationships for details). Table 1 contains descriptive statistics for all primary study variables.

Aim 1: change in presumptuous romantic intentions

Though presumptuous romantic intentions before the pandemic significantly predicted presumptuous romantic intentions during the pandemic (b = 0.54, se = 0.14, p < 0.001, 95% CI[0.25, 0.82]), the hypothesized increase in presumptuous romantic intentions was not observed. Instead, individuals’ presumptuous romantic intentions decreased significantly from Time 1 (M = 3.38, SD = 1.02) to Time 2 (M = 2.82, SD = 0.98), t(77.93) = 2.58, p = 0.012, 95% CI[0.13, 1.00], d = 0.56, which corresponds to a medium effect of approximately half a standard deviation in presumptuous romantic intentions.

Aims 1 and 2: predictors of change in presumptuous romantic intentions

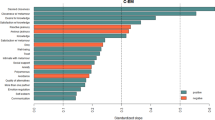

To examine changes in presumptuous romantic intentions from before to during the pandemic, we estimated a linear model in which difference scores (Time 2—Time 1; higher scores indicate greater intentions during COVID-19) were regressed onto COVID-induced relatedness frustration, negative fantasy valence, and negative fantasy intrusiveness (see Fig. 1). The model intercept indicates the average change in presumptuous romantic intentions from Time 1 to Time 2 (b = -0.57, se = 0.14, p < 0.001, 95% CI[-0.86, -0.28]). Contrary to our Aim 1 hypothesis, subjective reports of COVID-induced relatedness frustration predicted a greater decrease in presumptuous romantic intentions during the pandemic (b = -0.53, se = 0.26, p = 0.054, 95% CI[-1.07, 0.01]). In line with our Aim 2 hypothesis, however, fantasy negativity (b = 0.41, se = 0.14, p = 0.004, 95% CI[0.14, 0.68]) and the intrusiveness of these negative fantasies (b = 0.31, se = 0.13, p = 0.026, 95% CI[0.04, 0.57]) both predicted a dampened decline in presumptuous romantic intentions from before to during the pandemic. Together, these three predictors explained 38.6% of the variance in changes in presumptuous romantic intentions. Notably, this pattern of results is analogous whether using difference scores (as above) or a residualized change score (Time 1 intentions predicting Time 2 intentions).

Predicting Differences in Presumptuous Romantic Intentions From COVID-induced Relatedness Frustration and Negative Fantasies in Study 1. Note. Values above the dashed line indicate an increase in presumptuous romantic intentions during the pandemic, whereas values below the line indicate a decrease from before to during the pandemic. Bars above and to the right of each plot represent the distribution of scores for the variable on the corresponding axis

Brief discussion, study 1

In Study 1, we investigated Aims 1 and 2 regarding intentions to pursue a romantic interest via presumptuously as a function of COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies. Study 1 addressed Aim 1 in two ways: first, the “natural experiment” of the onset of social mitigation measures to combat the pandemic allowed us to interpret overall changes in presumptuous romantic intentions from Time 1 to Time 2 through the lens of a pervasive relatedness threat for all participants. We hypothesized that presumptuous romantic intentions would increase from before to during the pandemic. Interestingly, the opposite pattern emerged— presumptuous romantic intentions decreased by more than half of a standard deviation from before to during the pandemic. Second, individual differences in COVID-induced relatedness frustration at Time 2 negatively predicted changes in presumptuous romantic intentions. By both metrics, the Aim 1 hypothesis was contradicted.

Although these findings are not in line with predictions, they are not surprising. Higher scores at Time 1 may reflect an initial elevation bias in reporting (Shrout et al., 2018), instead of veridical reporting on presumptuous romantic intentions. Alternatively, it seems reasonable reductions in presumptuous romantic intentions are a reflection of the average participant’s tendency to follow public health guidelines to stay home and minimize social contact (even though they were instructed to respond at Time 2 as if such restrictions were not in place). Indeed, during the pandemic, relatedness threats are confounded with worries about getting or transmitting COVID-19—both in theory and in our measure of relatedness frustration. Especially early in the pandemic (T2), when the edict was “social distancing,” before the more apt “physical distancing,” individuals may not have developed strategies for safely pursuing romantic connections. It is also possible that stay-at-home orders made critical opportunities for pursuit less salient, thereby reducing intentions. Regardless, the decrease in intentions is reflective of how the COVID-19 context shapes relatedness need fulfillment.

Study 1 also addressed Aim 2, testing whether negative fantasies about a romantic interest correlate with (changes in) presumptuous romantic intentions. Consistent with prior experimental work (Valshtein et al., 2020), the decrease in presumptuous romantic intentions from Time 1 to Time 2 attenuated to zero when individuals reported above-average levels of negative fantasies. This means that individuals in this sample who had highly negative fantasies during COVID-19 retained pre-COVID levels of presumptuous romantic intentions, whereas their counterparts low in negative fantasies reduced their intentions. Although this was not a formal test of our Aim 3 interaction hypothesis, it seems that when the socially restricted COVID context is followed by negative fantasies, individuals “double down” on potentially problematic pursuit of a romantic interest.

The lack of a true experimental design and the small sample size of this natural experiment led us to interpret these findings with caution. However, given the uniqueness of our “natural experiment” amidst a once-in-a-generation pandemic, replication is not an option to bolster these findings. Thus, to better understand the role of subjectively experienced COVID-induced relatedness frustration, negative fantasies, and their interaction in predicting presumptuous romantic intentions, a second study was conducted to investigate how these processes unfold daily under COVD-19 social mitigation guidelines.

Study 2

Study 2 was designed to expand upon Study 1 by capitalizing on a daily diary approach to understanding the effects of COVID-19 social mitigation guidelines on how people pursue new and maintain existing relationships. Collecting daily reports allows us to quantify the degree to which presumptuous romantic intentions, regarding a non-cohabiting romantic partner or romantic interest, fluctuate as a function of individuals’ daily, lived experience of COVID-19. Not only will this design enable us to explore both between- and within-person effects of COVID-induced relatedness frustration, negative fantasies, and their interactions (i.e., Aims 1–3), but this also represents the first attempt to use longitudinal methods to study stalking-like behaviors.

Both COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies are expected to predict presumptuous romantic intentions at both the between-person and within-person level, in line with Valshtein et al. (2020). Specifically, individuals who report subjectively more COVID-induced relatedness frustration (Aim 1) and negative fantasies (Aim 2) on average will report greater presumptuous romantic intentions. However, because the Study 1 findings cast doubt on COVID-induced relatedness frustration as a positive predictor of presumptuous romantic intentions, we could alternatively observe, as in Study 1, relatedness frustration corresponding to reduced presumptuous romantic intentions. With this intensive longitudinal design, within-person predictions regarding Aims 1 and 2 are also possible. Valshtein et al. (2020) experimentally-induce relatedness threats and negative fantasies, and so those findings may represent an acute, situational phenomenon akin to the within-person fluctuations one might experience when reporting daily experiences. Accordingly, we hypothesize that on days when a participant reports more COVID-induced relatedness frustration or negative fantasies as compared to their own average, they will report greater presumptuous romantic intentions.

Finally, we predict there to be both between-person and within-person interactions (Aim 3). More precisely, for individuals who report greater COVID-induced relatedness frustration than the average person, the between-person effect of negative fantasies will be more closely associated with presumptuous romantic intentions. Similarly, on days when individuals report greater than their usual COVID-induced relatedness frustration, the within-person effect of negative fantasies will be more closely associated with presumptuous romantic intentions.

In Study 2, we will capture the degree of heterogeneity in our primary within-person associations of interest (Aim 4)—the first such attempt in research on presumptuous romantic intentions. Specifically, we anticipate significant heterogeneity in COVID-induced relatedness frustration as a predictor of presumptuous romantic intentions: that is, for some individuals, daily frustrations will be more predictive, whereas for other people, daily frustration will be less predictive—possibly even negatively predictive—of presumptuous romantic intentions. This hypothesis is based on our unexpected Study 1 findings and on research suggesting that individuals vary in their ability to manage the social ramifications of COVID-19 (Luchetti et al., 2020). Similarly, we anticipate significant heterogeneity in negative fantasies as a predictor of presumptuous romantic intentions. In line with research on responses to rejection (Smart Richman & Leary, 2009), for some people, negative fantasies about a romantic interest may strongly predict compensatory presumptuous romantic intentions, whereas other negatively fantasizing individuals may withdraw and be less likely to act. Using a recently developed approach (Bolger et al., 2019), we investigate heterogeneity by estimating random slopes for each predictor. Studying heterogeneity allows us to precisely quantify the degree to which a fixed effect is generalizable and, in doing so, prompts avenues for future research into what factors explain such heterogeneity.

Method, study 2

Participants

We recruited 282 undergraduate students during the second COVID-19 wave, which occurred in the U.S. in late-October 2020. Due to COVID-19 restrictions and remote learning, participants were located across 18 different states, with an additional 36 students reported residing outside the U.S.Footnote 2 A total of 15 participants failed at least one of two attention checks and were subsequently removed from analysis. Of the participants who completed the baseline survey, 233 participated in the daily diary surveys, and 8 participants had missing or incomplete data preventing us from identifying and matching diary entries. Despite recruiting participants who were specifically not cohabitating with a romantic partner, 14 individuals reported currently residing with their romantic partner and were thus removed. Of the remaining 211 participants, 15 failed to complete at least 4 diary days and were subsequently removed from analyses. Two additional participants were removed because their responses failed to vary across items.

Following this preliminary cleaning, the final sample consisted of 194 participants, 141 of whom completed all 7 diary days, 41 of whom completed 6 days, 13 of whom completed 5 days, and 6 of whom completed 4 diary days. Our sample—77.8% of whom were heterosexual—comprised 49 men, 141 women, and 4 trans or gender nonbinary participants. Of the 194 final participants, 67 were in non-cohabiting romantic relationships, and the other 127 individuals had a romantic interest. Finally, our sample was also racially and ethnically heterogeneous: 40.2% identified as Asian, 19.0% identified as multiracial or some other racial/ethnic group, 17.5% identified as White, 11.9% identified as Black, 11.3% identified as Latinx, and 0.1% identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native.

Procedure

Baseline survey

After consent, participants reported their relationship status as in Study 1. The name of participants’ romantic interest was again inserted into all subsequent questions pertaining to the romantic interest. Participants then completed the measures described below as “Baseline.” Participants spent a median 10.01 min (MAD = 298 s) on the baseline survey.

Daily diary surveys

Every day for seven days, starting the day after completing the baseline survey, participants were sent one brief daily diary survey that took a median 1.47 min (MAD = 47.44 sec) to complete. Because the sample comprised students remote learning from a variety of locations, subsequent daily diary surveys were sent at the time in which the initial baseline survey was completed. To reduce nuisance variability in item responses, participants answered each item with respect to only the past day in which they were responding. On the last day of the survey, participants were shown a debriefing form with the study aims, basic information about the design, related publications, and the option to remove their data from analysis. Because the sample comprised undergraduate students, they were compensated with course credit.

Measures

Baseline COVID-induced relatedness frustration

Participants were asked about COVID-induced relatedness frustration over the past month using the same 6 items about both responses to COVID-19 and loneliness from Study 1. However, in an attempt to better tap into the relatedness frustrating nature of the pandemic, in Study 2 participants also responded to one item regarding the extent to which COVID-19 interfered with their ability to make romantic connections. All 7 items were standardized and centered, then created an average (α = 0.80). Higher scores indicated greater COVID-induced relatedness threat. As in Study 1, participants again reported on their adherence to social distancing practices and their perceived seriousness of COVID-19 pandemic.

Baseline negative fantasies

To measure negative fantasies, individuals responded to the same two items as in Study 1, modifying the time scope of the question to evaluate fantasies in the past two weeks. These items were averaged for a baseline indicator of negative fantasies. Like in Study 1, participants reported on the intrusiveness of these fantasies on a 1 to 7 scale where higher scores indicated more negative and more intrusive fantasies (anchors varied by item). Participants also reported on how frequently they “fantasized about < ROMANTIC INTEREST > ” in the past month, on a scale from 0 (Never) to 6 (All the Time), as a potential covariate. Positive fantasies were assessed in the same manner but were not included in analyses.

Baseline demographics and other covariates

As in Study 1, participants reported on demographic questions including age, race, gender, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status, as well as several exploratory measures, including perceived stress (Cohen et al., 1983), mental health (Kroenke et al., 2009), attraction to the romantic interest, and relationship expectations, efficacy, and relationship commitment. Finally, at two points in the baseline survey, attention checks were embedded (e.g., “If you are reading this statement, please leave this item blank”).

Daily COVID-induced relatedness frustration

The same seven-item measure of COVID-induced relatedness frustration from was included, except participants responded only based on how they felt over the past day. Again, all 7 items were standardized, centered, and averaged to create a scale score for each day. Following recommendations by Cranford and colleagues (2006), the reliability of change was estimated using a variance components analysis and found this measure could reliably detect individual change across the diary period (Rc = 0.76).

Daily negative fantasies

Daily negative fantasies were assessed using one item: “In the past day, how often did you have negative fantasies about < ROMANTIC INTEREST > .” Participants responded on a 1 (Never) to 7 (All the Time) scale. Participants also responded to one item about the intrusiveness of their fantasies that day. As with assessment of baseline fantasies, participants also reported on positive fantasies for exploratory purposes.

Daily presumptuous romantic intentions

The same 13-item measure of presumptuous romantic intentions was used in Study 2. Unlike in Study 1, participants reported on their presumptuous romantic intentions with respect to a specific romantic interest. To ensure that they thought about the same interest while responding to these items, the name and pronouns of the romantic interest they listed at baseline was piped into each item (e.g., “Check up on < ROMANTIC INTEREST > through mutual acquaintances/friends”). Following the same approach (Cranford et al., 2006), the composite score of these 13 items was a reliable measure for detecting change (Rc = 0.78).

Daily diary additional questions

Finally, at the end of the seventh diary day, participants responded to two additional items about their relationship to their romantic interest: first, whether they knew where their romantic interest currently resided (yes/no), and second, how easily they could locate their romantic interest (from 1, not at all easy, to 7, extremely easy).

Results, study 2

Data analytic plan

We estimated a multilevel model to test the influence of between-person differences and within-person changes in COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies on presumptuous romantic intentions. Prior to estimation, “between-person” and “within-person” effects were disaggregated for both COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies. To calculate between-person effects, participants’ average score across all diary days was computed and then subtracted the overall sample average from an individual’s average. A between-person effect can be interpreted as a person’s average level of the predictor, or how much a given person’s average score deviates from the sample average. To calculate within-person effects, a person’s average score was subtracted from their daily score. This can be interpreted as how much a person deviates from their own average on a given day.

Because the interaction between COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies was of interest, interaction terms were computed for both between-person and within-person effects. This allows for the interpretation of both the interaction between people who are above average in their COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies, as well the interaction on days when people are above their own average for relatedness frustration and negative fantasies. We estimated all models using restricted maximum likelihood. In the final model,Footnote 3 fixed effects as seen in the variable column of Table 3 were entered. Importantly, a random intercept for each individual was specified, as well as random slopes for within-person COVID-induced relatedness frustration and within-person negative fantasies. This approach estimates unique effects of COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies for each individual.

Descriptive statistics

Daily means and standard deviations for study variables are in Table 2, along with the between-person and within-person correlations of presumptuous romantic intentions, COVID-induced relatedness frustration, and negative fantasies. Between-person correlations are associations between individuals’ average score across all diary days. The within-person correlations represent individuals’ change on a given day relative to their own average across all diary days.

Aims 1 and 2: fixed effects of COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies

Looking at the fixed effects of our model (see Table 3), which represent the effects for the average, or typical participant, several notable findings emerge. First, we found a negative effect of day, such that with each passing day people reported lower presumptuous romantic intentions. A weekend effect was also observed, whereby people reported higher presumptuous romantic intentions on the weekend compared to the week. People in relationships reported greater presumptuous romantic intentions than single individuals. Individuals who reported fantasizing about their romantic target more frequently over the past month—whether positively or negatively—also reported greater presumptuous romantic intentions.

Pertinent to the main hypotheses, no significant fixed effect for between-person COVID-induced relatedness frustration was observed (b = 0.10, se = 0.11, p = 0.39). On the other hand, there was a positive between-person effect of negative fantasies, such that people who are higher than average in negative fantasies report more presumptuous romantic intentions (b = 0.19, se = 0.08, p = 0.01). Moreover, there was no significant association between either within-person COVID-induced relatedness frustration (b = 0.01, se = 0.05, p = 0.906) or negative fantasies (b = -0.02, se = 0.02, p = 0.28) and daily presumptuous romantic intentions.

Aim 3: interaction between COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies

Regarding Aim 3, there was a marginally significant interactions between COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies at the between-person and within-person levels (see Table 3 and Fig. 2). In looking more closely at the between-person interaction, simple slope analyses revealed that for individuals who were one standard deviation above the sample average in COVID-induced relatedness frustration, negative fantasies predicted greater presumptuous romantic intentions, which supported our hypothesis, (b = 0.31, se = 0.09, p = 0.001). The effect of negative fantasies for someone one standard deviation below average in relatedness frustration, in contrast, was not significant, (b = 0.07, se = 0.10, p = 0.47).

In looking at the interaction at the within-person level, the pattern of results is in the opposite direction of the between-person interaction. Here, simple slope analyses reveal that on days when an individual was one standard deviation above their typical COVID-induced relatedness threat, negative fantasies predicted significantly less presumptuous romantic intentions (b = -0.05, se = 0.02, p = 0.02). The effect of negative fantasies on a day when someone is one standard deviation below their typical COVID-induced relatedness frustration was not significant (b = 0.01, se = 0.03, p = 0.62).

Aim 4: random effects for COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies

We specified a random intercept for participants, as well as random effects for both COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies to understand heterogeneity of both within-person effects. As recommended by Bolger and colleagues (2019), we evaluated this heterogeneity with three criteria: the uncertainty interval of the random effects, comparative model fit, and relative size of the random effects as compared to the fixed effects. We found substantial variability in individuals’ expected level of presumptuous romantic intentions, as estimated with a random intercept (sd = 0.92, 95% CI[0.82, 1.01]). Specifically, individuals’ intercepts ranged from the lowest possible value on the 1–7 scale (b0 = 1.00) to much higher (b0 = 3.48).

As displayed in Fig. 3, there also appears to be meaningful heterogeneity in the within-person effect of COVID-induced relatedness frustration on presumptuous romantic intentions. This means that although on average the effect of daily COVID-induced relatedness frustration was inconsequential for presumptuous behavior, this was not indicative of all individuals. As is reflected by the panel plot in Fig. 3, for some people COVID-induced relatedness frustration led to more presumptuous romantic intentions (participants #74 and #231), for others frustration had no association with presumptuous romantic intentions (participants #124 and #75), and for others they led to less presumptuous romantic intentions (participants #11 and #101). Individuals’ unique slopes, representing the association between COVID-induced relatedness frustration and intentions, were variable, with 95% ranging from -0.31 to 0.32 (see Fig. 3, vertical dashed lines). The uncertainty interval around the random effect was not close to zero (sd = 0.33, 95% CI[0.23, 0.41]). Importantly, the likelihood ratio test comparing this model including random slopes to the model with only random intercepts suggests a significant model improvement (LRT = 33.75, df = 2, p < 0.001). The size of the random effect (sd = 0.33) was more than 28 times the size of the fixed effect (b = 0.013). Taken together, the presence of this random effect indicates that there is significant heterogeneity in how COVID-induced relatedness frustration influences presumptuous romantic intentions.

Representative Participant Slopes (left) and Distribution of Slopes (right) for COVID-induced Relatedness Frustration Predicting Daily Presumptuous Romantic Intentions in Study 2. Note. In the left-hand plot, numbers above each panel represent that participant’s randomly designated ID. In the right-hand plot, the black line represents the fixed effect, and the dashed red lines indicate a 95% confidence interval computed from the random effect

Evidence for a similar pattern in negative fantasies did not emerge: a likelihood ratio test did not suggest improved model fit from a random slope of negative fantasies (LRT = 4.28, df = 3, p = 0.23), and the uncertainty interval around the random effect (sd = 0.048) was not close to zero (95% CI[0.02, 0.11]), even though the relative size of the heterogeneity was sufficiently large (> 25% of the fixed effect). It was accordingly omitted from the final model. Thus, although there were meaningful differences in individuals’ effect of COVID-induced relatedness frustration on presumptuous romantic intentions, this was not the case for negative fantasies.

General discussion

Across two studies during two different waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, we found some evidence for the notion that relatedness frustration predicts how ardently individuals intend to pursue or develop a romantic relationship. We addressed four primary aims: to examine COVID-induced relatedness frustration (Aim 1), negative fantasies (Aim 2), and their interaction (Aim 3) as predictors of intentions to presumptuously pursue a romantic interest; and, finally, to examine the heterogeneity of the within-person effects of COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies (Aim 4).

With respect to Aim 1, presumptuous romantic intentions unexpectedly decreased during the pandemic (Study 1), despite the onset of the pandemic representing a threat to relatedness. Also contrary to expectations, individuals with greater COVID-induced relatedness frustration during the pandemic showed a stronger decrease in presumptuous romantic intentions in Study 1. Further complicating these results, in Study 2 we failed to observe significant fixed effects of COVID-induced relatedness frustration on presumptuous romantic intentions at either the between-person or within-person level. The original hypothesis—that pandemic-related social mitigation regulations would threaten relatedness and the resulting relatedness need frustration would in turn increase presumptuous romantic intentions—was not supported.

In hindsight, these contradictory, mixed Aim 1 findings may reveal a possible boundary condition on the needs-as-motives notion (Prentice et al., 2014). Just as the pandemic threatened relatedness needs, it also threatened physical health needs, which surely took precedence over relational needs—especially concerning early-stage, tentative romantic connections. When rising case numbers fueled these safety concerns, along with the subjective experience of relatedness-frustrating social mitigation policies, people might reasonably have reduced their presumptuous romantic intentions. This would explain our Study 1 findings, with presumptuous romantic intentions decreasing both during the relatedness threatening COVID-19 context and as a function of greater reported relatedness frustration. Individuals may have also relied more on family and friends for a sense of community through shared adversity (Luchetti et al., 2020), relative to developing new romantic connections. In Study 2, where there were null results on average for relatedness frustration as a predictor, the same social withdrawal for safety was still plausible, but to a lesser degree. More than six months following its U.S. onset, people may have acclimated to changes in social interaction norms and accordingly developed new strategies for connection. Perhaps it was easier for Study 2 participants to imagine themselves making romantic advances that were not tied to risky in-person behaviors, thus enabling the relatedness frustration to spur presumptuous romantic intentions in some individuals—an interpretation supported by our finding meaningful heterogeneity in the within-person effect of relatedness frustration. Future research may examine other circumstances in which relatedness and safety needs are seemingly at odds to gain a better understanding of why our Aim 1 predictions were not upheld.

In support of Aim 2, in Study 1 negative fantasies predicted a diminished decrease in presumptuous romantic intentions from before to during the pandemic. We replicated the positive association between negative fantasies and presumptuous romantic intentions in Study 2, at the between-person level. People who negatively fantasized more often than the rest of the sample also reported more daily presumptuous romantic intentions. Our results replicate work (Valshtein et al., 2020) finding that people more prone to negative fantasies are also more prone to preoccupation with a romantic interest. Further, this work extends Valshtein et al. (2020) in three important ways: first, with presumptuous romantic intentions as the focal outcome, rather than obsessive thinking, this research advances understandings of stalking-like behaviors. Second, in finding the same pattern as Valshtein et al. (2020) amidst a global pandemic, which demonstrates the robustness of negative fantasies as a predictor in this domain, holding true even in an unusual context for developing romantic relationships. Third, the effects Valshtein et al. (2020) found with experimentally induced negative fantasies were observed with naturally-occurring differences.

Interestingly, in Study 2, self-reports of daily fluctuations in negative fantasies (i.e., the within-person effect) were not predictive of presumptuous romantic intentions. If a within-person effect of negative fantasies does exist, perhaps it plays out on a larger timescale than We could observe with daily measures over one week. Future work should continue to probe whether within-person changes in negative fantasies also predict presumptuous romantic intentions.

Concerning Aim 3, we observed modest interactions between COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies both between-persons and within-persons (e.g., on the daily level). Conceptually replicating the pattern found by Valshtein and colleagues (2020), For individuals who tended to experience more COVID-induced relatedness frustration on average, between-person differences in negative fantasies more strongly predicted presumptuous romantic intentions. Our findings imply that individual differences in negative fantasizing are especially predictive of romantic pursuit when frustrating basic psychological need for relatedness are also considered.

Unlike previous literature, we also observed an interesting within-person interaction, such that on days when a person experienced more COVID-induced relatedness frustration than was typical for them, daily negative fantasies were associated with lower daily presumptuous romantic intentions. Perhaps the combination of higher-than-usual COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies within an individual reflected a level of difficulty in romantic pursuit that was too high to summon the effort required to pursue presumptuously (Sciara & Pantaleo, 2018). Future work is needed to expand on this novel investigation of within-person predictors of daily presumptuous romantic intentions.

In Study 2, we also hypothesized—and partially observed—that there would be heterogeneity in the extent to which both COVID-induced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies predicted presumptuous romantic intentions. Although the average association between individuals’ COVID-induced relatedness frustration and presumptuous romantic intentions was not significant, the effect was idiosyncratic. For some, COVID-induced relatedness frustration was associated with lower reported presumptuous romantic intentions; yet, for others COVID-induced relatedness frustration predicted more presumptuous romantic intentions. Smart Richman and Leary’s (2009) multimotive model of rejection offers a compelling interpretation: with several motivated responses available to address relatedness threats, individuals who reported lower presumptuous romantic intentions when they had greater COVID-induced relatedness frustration may have engaged in alternative responses like social withdrawal. Future research should explore possible moderators explaining the heterogeneity in this effect–for example, relationship commitment, relationship quality, or feasibility of pursuit. Notably, less clear evidence emerged for heterogeneity in the negative fantasy effect.

Implications

The present research builds upon growing literature on the social ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our research elaborates on the intuitive idea that COVID-19 should interfere with pursuit of romantic connections (e.g., Luetke et al., 2020). Specifically, our work advances current understandings of how contextual factors (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) interact with social-cognitive factors (e.g., negative fantasies) to determine people’s motivation to form and maintain meaningful romantic connections via presumptuous strategies. Accordingly, our work contributes to the body of work demonstrating meaningful heterogeneity in how and when psychological need frustration can increase risk for maladjustment (Valshtein et al., 2020).

Unlike much research on romantic relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic, our sample comprised individuals who are not in serious relationships—or at least not serious enough to be cohabitating. However, the work that most closely informed our hypotheses (Valshtein et al., 2020) examined individuals in relationships ranging from 1.5 to 9 years on average and experimentally induced negative fantasies. In the present research, where the need threat was naturally-occurring, the role of spontaneously-reported negative fantasies, as measured, may have been diminished because people constructively addressed the relatedness threats prior to reporting on their fantasies and intentions. In other words, this naturalistic test produced weaker effects because individuals were able to quickly experience negative fantasies and engage in strategies to attenuate fantasies, all before the daily survey was administered. This caveat is consistent with findings that lab studies in social psychology often yield larger effect sizes than field studies (Mitchell, 2012).

Our results contribute to the growing body of research on problematic interpersonal behaviors (Kaukinen, 2020) and intimate partner violence (Jarnecke & Flanagan, 2020) in light of the limited social landscape caused by COVID-19. Although an average decline in presumptuous romantic intentions compared to before the pandemic was observed, COVID-19 lockdowns have raised concerns regarding an elevated risk of stalking (Bracewell et al., 2020) and intimate partner violence (Jarnecke & Flanagan, 2020). Using a multilevel model specified with random effects, we examined variation in the extent to which psychological mechanisms—relatedness frustration and negative fantasies—may be contributing to the uptick in perpetration. Future research should focus on identifying for whom experienced relatedness frustration and negative fantasies are most likely to facilitate presumptuous romantic intentions, and on what aspects of the social environment amidst a global pandemic might lead individuals to set and follow through on such intentions.

The present research advances our understanding of potentially unwanted romantic behavior beyond the COVID-19 context, as it is the first attempt to investigate within-person variability in stalking-like behavior. Researchers have previously discussed (e.g., Ali & Naylor, 2013) whether such forms of intimate partner violence are facilitated via situationally-elicited cultural messages that promote “stalking culture” (e.g., Becker et al., 2020) or via dispositional, evolutionary tendencies (e.g., Buss & Duntley, 2011). Assessing both dispositional (between-person) and situational (within-person) effects using daily diary methods may afford us new insights into these questions. For example, this approach may be especially useful in studying how gender differences emerge, such as quantifying the degree to which problematic romantic behaviors are predicted by gender role attitudes (between-person effect) or contextual factors like cultural messages or mood (within-person effects).

Beyond moderators and mechanisms at between- and within-person levels, time is also worthy of more scrutiny. There are two ways in which the effects of time should be further explored: interval and dyadic timing. First, selecting an appropriate time interval may lend itself to more effectively capturing variability in presumptuous romantic intentions. For example, relatively low endorsement of daily intentions was observed; however, using a different measurement interval (e.g., weekly) might be more conceptually-aligned with actual variability in intentions. Second, future work should consider the timing of romantic behaviors with respect to the needs of the romantic interest. What differentiates an uncomfortable stalking-like blunder from a suave courtship maneuver may be a matter of synchrony between a behavior and its intended recipient (e.g., McClure, 2011). Conceptualizing relationship formation as a dyadic process that unfolds over time has been a fruitful approach to explaining other relationship processes, but researchers have yet to extrapolate this approach to relationship formation.

In the present research, we assessed individuals’ presumptuous romantic intentions, not their actual behaviors. Given robust findings detailing the intention-behavior gap (Sheeran, 2002), it is likely that our participants did not always act in accordance with their intentions. However, studying intentions rather than actual behaviors may in fact be a strength. Not only are intentions one of the strongest predictors of actual behavior (for a review, see Sheeran, 2002), but because intentions precede behavior, targeting them as an outcome may be an effective research strategy for preventing problematic relationship behaviors before they occur. In the context of early waves of COVID-19, assessing intentions likely allowed us to tap into meaningful variability that could not have been gleaned from assessing behaviors, which were likely limited by public safety restrictions. Future research should continue to explore early predictors of more extreme stalking behaviors, the intention-behavior gap in romantic pursuit, and potential interventions to promote more effective relationship strategies. Ultimately, more research in this vein will have critical intervention implications, such as whether to target harm reduction messaging to a select few individuals or to everyone, under select circumstances.

In sum

In two studies during the COVID-19 pandemic, a complex picture emerged for how potentially relatedness threatening experiences—whether large scale social mitigation measures or idiosyncratic negative future fantasies—come to bear on navigating the early phases of romantic relationships. Individuals with a greater tendency to negatively fantasize about a romantic interest had greater intentions to pursue them via presumptuous means. And this was especially the case for individuals experiencing the pandemic as frustrating their need for relatedness. As bell hooks (2001, p.147) describes, “love allows us to enter a paradise. Still, many of us wait outside the gates, unable to cross the threshold, unable to leave behind all the stuff we have accumulated that gets in the way of love.” Amidst a global pandemic, the gates of paradise have become more imposing, reflected in the overall decrease in presumptuous romantic intentions from the pandemic’s onset. Yet, however misguided their attempts may be, many continue to seek entrance into the gates of paradise. By investigating predictors of problematic relationship behaviors—the “stuff that gets in the way of love”—we can better protect romantic pursuers from the biting pangs of disconnection and protect the pursued from harmful, unwanted romantic advances.

Data availability

All supplemental analyses, data, materials, and code are available at https://bit.ly/sociallydistantrelationships

Notes

The supplementary materials (https://bit.ly/sociallydistantrelationships) contain a more thorough psychometric evaluation of this measure. A single factor model fit the data reasonably well.

Meaningful as not observed in any of the primary measures based on participants’ reported location (17 + states).

An initial model with theoretically-relevant covariates was fit in order to ensure the model was specified properly. For brevity, only the final model is presented–though the pattern of results is analogous across models. These analyses can be found in the online supplemental materials.

References

Ali, P. A., & Naylor, P. B. (2013). Intimate partner violence: A narrative review of the feminist, social and ecological explanations for its causation. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(6), 611–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2013.07.009

Balzarini, R. N., Muise, A., Zoppolat, G., Di Bartolomeo, A., Rodrigues, D. L., Alonso-Ferres, M., et al. (2020). Love in the time of COVID: Perceived partner responsiveness buffers people from lower relationship quality associated with COVID-related stressors. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 19485506221094437. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506221094437

Becker, A., Ford, J. V., & Valshtein, T. J. (2020). Confusing Stalking for Romance: Examining the Labeling and Acceptability of Men’s (Cyber)Stalking of Women. Sex Roles. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01205-2

Bolger, N., Zee, K. S., Rossignac-Milon, M., & Hassin, R. R. (2019). Causal processes in psychology are heterogeneous. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(4), 601. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000558

Bracewell, K., Hargreaves, P., & Stanley, N. (2020). The Consequences of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Stalking Victimisation. Journal of Family Violence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00201-0

Buss, D. M., & Duntley, J. D. (2011). The evolution of intimate partner violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 16(5), 411–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.04.015

Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Duriez, B., Lens, W., Matos, L., Mouratidis, A., Ryan, R. M., Sheldon, K. M., Soenens, B., Van Petegem, S., & Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

Cranford, J. A., Shrout, P. E., Iida, M., Rafaeli, E., Yip, T., & Bolger, N. (2006). A Procedure for Evaluating Sensitivity to Within-Person Change: Can Mood Measures in Diary Studies Detect Change Reliably? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(7), 917–929. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206287721

Cupach, W. R., & Spitzberg, B. H. (1998). Obsessive relational intrusion and stalking. In B. H. Spitzberg & W. R. Cupach (Eds.), The dark side of close relationships (pp. 233–263). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Cupach, W. R., Spitzberg, B. H., Bolingbroke, C. M., & Tellitocci, B. S. (2011). Persistence of Attempts to Reconcile a Terminated Romantic Relationship: A Partial Test of Relational Goal Pursuit Theory. Communication Reports, 24(2), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2011.613737

Doron, G., & Kyrios, M. (2005). Obsessive compulsive disorder: A review of possible specific internal representations within a broader cognitive theory. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(4), 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.02.002

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Moskowitz, G. B. (1996). Goal effects on action and cognition. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 361–399). The Guilford Press.

Hooks, Bell. (2001). All about love: New visions. Harper Perennial.

Jarnecke, A. M., & Flanagan, J. C. (2020). Staying safe during COVID-19: How a pandemic can escalate risk for intimate partner violence and what can be done to provide individuals with resources and support. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S202–S204. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000688

Kaukinen, C. (2020). When Stay-at-Home Orders Leave Victims Unsafe at Home: Exploring the Risk and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence during the COVID-19 Pandemic. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 1–12,. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09533-5

Kazarian, S. S., & McCabe, S. B. (1991). Dimensions of social support in the MSPSS: Factorial structure, reliability, and theoretical implications. Journal of Community Psychology, 19(2), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(199104)19:2%3c150::AID-JCOP2290190206%3e3.0.CO;2-J

Knee, C. R., Hadden, B. W., Porter, B., & Rodriguez, L. M. (2013). Self-Determination Theory and Romantic Relationship Processes. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868313498000

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2009). An Ultra-Brief Screening Scale for Anxiety and Depression: The PHQ–4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), 613–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(09)70864-3

Lehmiller, J. J., Garcia, J. R., Gesselman, A. N., & Mark, K. P. (2020). Less Sex, but More Sexual Diversity: Changes in Sexual Behavior during the COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Leisure Sciences, 1–10,. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1774016

Luchetti, M., Lee, J. H., Aschwanden, D., Sesker, A., Strickhouser, J. E., Terracciano, A., & Sutin, A. R. (2020). The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. American Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000690

Luetke, M., Hensel, D., Herbenick, D., & Rosenberg, M. (2020). Romantic Relationship Conflict Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic and Changes in Intimate and Sexual Behaviors in a Nationally Representative Sample of American Adults. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 46(8), 747–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2020.1810185

Matias, T., & Marks, D. F. (2020). Human needs in COVID-19 isolation. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(7), 871–882. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105320925149

McClure, M. J. (2011). Hopes of affiliation and fears of rejection: The effects of attachment anxiety on behaviour and outcomes in initial interactions. Library and Archives Canada = Bibliothèque et Archives Canada.

Mitchell, G. (2012). Revisiting Truth or Triviality: The External Validity of Research in the Psychological Laboratory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611432343

Oettingen, G. (2012). Future thought and behaviour change. European Review of Social Psychology, 23(1), 1–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2011.643698

Oettingen, G., & Mayer, D. (2002). The motivating function of thinking about the future: Expectations versus fantasies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(5), 1198–1212. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1198

Oettingen, G., Pak, H., & Schnetter, K. (2001). Self-regulation of Goal Setting: Turning Free Fantasies about the Future into Binding Goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 736–753. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.80.5.736

Pietromonaco, P. R., & Overall, N. C. (2020). Applying relationship science to evaluate how the COVID-19 pandemic may impact couples’ relationships. American Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000714

Prentice, M., Halusic, M., & Sheldon, K. M. (2014). Integrating Theories of Psychological Needs-as-Requirements and Psychological Needs-as-Motives: A Two Process Model. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8(2), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12088