Abstract

According to social learning theory, we examine the effect of ethical leadership by investigating how moral identity resulting from ethical leadership influences employees’ workplace cheating behaviors. Adopting a moderated mediation framework, this study suggests that leader-follower value congruence moderates the positive relationship between ethical leadership and employees’ moral identity and mitigates the indirect effect of ethical leadership on employees’ workplace cheating behaviors. The results of this study, drawn from a sample of 243 full-time employees and their direct supervisors, support these hypotheses. As such, this study provides novel theoretical and empirical insights into ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Workplace cheating behavior, defined as “acts that are intended to create an unfair advantage or help attain benefits that an employee would not otherwise be entitled to receive” (Mitchell et al., 2018: 54), is common and can create substantial costs to organizations. Estimates suggested that more than 33.3% organizations existed cheating incidents (Pricewaterhouse Coopers, 2014). Moreover, according to Goman (2013), workplace cheating behavior may cost organizations billions of dollars every year, which accounts for about 7% of annual revenue. How to inhibit cheating behavior in the workplace is therefore a critical issue. Yet exploring the antecedents of workplace cheating behavior becomes an important agenda for researchers (Ballantine et al., 2018; Men et al., 2021; Mitchell et al., 2018). Considerable empirical evidence attests to the antecedents of cheating behavior. For example, studies have indicated a positive relation between temptation (Pate, 2018), COVID-19 (Hillebrandt & Annika, 2022), underdog expectation (Loi et al., 2021), customer mistreatment (Men et al., 2021), peer influence (Malesky et al., 2022), performance pressure (Mitchell et al., 2018) and cheating behavior. Concomitantly, prior work has suggested a negative relation between corporate social responsibility and cheating behavior (Luan et al., 2021).

Due to the prevalence and far-reaching role of leadership in the workplace (Shin & Zhou, 2003), one critical situational factor that may have potential influence on workplace cheating behavior is leadership (Greenbaum et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2018). Ethical leadership, in particular, has been studied by leadership scholars in recent years (Avey et al., 2012; Byun et al., 2018; Men et al., 2020; Ogunfowora, 2014; Qin et al., 2018; Walumbwa et al., 2017). Ethical leadership refers to “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (Brown et al., 2005: 120). Indeed, previous research has examined the relationship between ethical leadership and unethical behavior (Lam et al., 2016; Paterson & Huang, 2019; Wang et al., 2019). For example, Paterson and Huang (2019) suggested that ethical leadership can inhibit followers’ unethical behavior through role ethicality. However, cheating behavior is distinct from unethical behavior (Mitchell et al., 2018). This is because cheating behavior focuses on the misrepresentation of employees’ own behavior, while unethical behavior is seen as violating societal norms for moral behavior (Appelbaum et al., 2007). Despite this kind of leadership’s potential influence on cheating behavior, to our knowledge, little research has focused on whether and how ethical leadership associates with employees’ workplace cheating behavior. An exception is the research by Mitchell et al. (2018), which conceptualized that ethical role models such as ethical leadership may exert a needed influence in reducing cheating. However, this pioneering study did not empirically test the relation between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior. Examining such effects is crucial because knowledge of the potential benefits of ethical leadership for an organization can be leveraged to aid leadership development and reduce workplace cheating behavior, which is attracting increased attention from management scholars and practitioners (Mitchell et al., 2018). Accordingly, a careful test of the relation between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior is warranted. Furthermore, the mechanism underlying the association between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior has yet to be learned. Uncovering the underlying process is crucial to fully understand how ethical leaders influence cheating behavior to prompt practitioners to effectively decrease cheating behaviors in the workplace. Thus, in this study, answering Mitchell et al.’ (2018) call for the examination of the effect of ethical leadership on cheating behavior, we aimed to examine whether and how ethical leadership affects cheating behavior.

In this study, we employed social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) to examine the relation between ethical leadership and cheating behavior. Social learning theory suggests that employees may learn appropriate behaviors from attractive role models (Bandura, 1977). Thus, by observing and emulating the normative behavior of ethical leaders (e.g., actively managing morality and treating people fairly), employees will not engage in workplace cheating behavior. Specifically, according to social learning theory (Bandura, 1977; Liden et al., 2014), ethical leadership can prompt employees’ moral identity, which refers to “the extent to which being a moral person is central to one’s self-definition” (Rupp et al., 2013: 904). This is because employees’ moral identity can be shaped through the learning process of observing, emulating, and learning ethical leaders’ moral values (Bavik et al., 2018). In addition, the cheating behavior literature suggests that moral identity can affect employees’ workplace cheating behavior (Mitchell et al., 2018). Thus, by integration the social learning theory and the cheating behavior literature, our study examines whether moral identity may play a mediating role in the relation between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior.

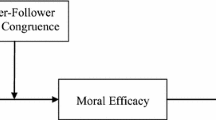

Additionally, we test the model of ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior through identifying a crucial boundary condition. Social learning theorists develop their perspectives in line with high leader-follower value congruence. Leader-follower value congruence refers to the perceived similarity between interests, values, and guiding principles concerning actions and decisions held by a leader and his or her follower (Jung & Avolio, 2000; Groves, 2014). Drawing on the similarity attraction argument (Pfeffer, 1983), similarity may induce an individual to appreciate one another’s positive attributes, and dissimilarity may provoke unfavorable treatment and less acceptance of another’s strengths due to social categorization processes. That is, if an employee has high value congruence with the leader, he or she will be more likely to attach importance to and emulate his or her leader’s behaviors with a positive point-of-view (Lee et al., 2017). Thus, according to social learning theory, if a leader demonstrates his or her possession of moral traits and acts in ethical ways such as treating people fairly, being an ethical example, and actively managing morality, the team members with high value congruence with the leader will be effectively mobilized to prompt moral identity, thereby inhibiting workplace cheating behavior. In addition, leader-follower value congruence has been viewed as a crucial contextual moderator in the literature of ethical leadership (Lee et al., 2017). Consequently, we attempt to investigate the boundary condition of the relation between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior by testing the moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Specifically, we theorize that leader-follower value congruence will moderate the indirect effect of ethical leadership on workplace cheating behavior via moral identity. That is, when value congruence is high, ethical leadership will be more likely to influence employees’ moral identity, which in turn will be negatively related to workplace cheating behavior (Fig. 1). Furthermore, we extend these results by examining the full theoretical framework with a moderated mediation model.

In proposing our social learning model of employee reactions to ethical leadership, we provide several contributions to the literatures of leadership and workplace cheating behaviors. First, our study offers the first empirical examination of whether ethical leadership negatively relates to workplace cheating behavior. Our study may advance current understanding of the consequences of the positive side of leadership in organizations. Second, our study crafted a theoretical framework uncover the mechanism via which ethical leadership affects workplace cheating behavior. Specifically, we build on social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) and moral identity perspective (Aquino & Reed, 2002) to propose a mediation model that connects ethical leadership to workplace cheating behavior. Third, we examined the moderating role of leader-follower value congruence in the indirect effect of ethical leadership on workplace cheating behavior via moral identity. Although ethical leadership may positively affect followers’ moral identity and thus inhibiting workplace cheating behavior, the degree to which ethical leadership affects (un-)ethical behavior may depend on leader-follower value congruence. In this study, we argue that leader-follower value congruence may play an important boundary condition in the relation between ethical leadership and moral identify, thereby affecting workplace cheating behavior. In addition, our findings offered practitioners a guide to leverage the positive effects of ethical leadership, thereby minimizing negative outcomes.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Ethical Leadership and Workplace Cheating Behavior

In our study, it proposes that the social learning principles (Bandura, 1977) will be helpful to explain the influence of ethical leadership on workplace cheating behavior. According to social learning theory, an individual can learn appropriate behaviors by observing the behaviors of others or a role-modeling process (Liden et al., 2014). That is, the behaviors showed by ethical leadership are likely to “trickle down” to subordinates to behave in a similar manner toward their colleagues (Mayer et al., 2012; Quade et al., 2017). In an organizational context, followers may assess the favorableness of the context by observing and interacting with their leaders (Huang & Paterson, 2017). Consequently, ethical leadership is considered to be a crucial factor influencing employees’ evaluations of the need to enhance and protect self-interests, and their decisions to engage in cheating behavior. Workplace cheating behavior requires employees to make judgments about the nature of the events and determines the need to enhance and protect their self-interests by cheating. While ethical leadership can offer clear clues to shape employees’ appropriate behaviors via personal ethical conduct (Bavik et al., 2018). Consequently, ethical leadership can affect workplace cheating behavior. Furthermore, ethical leadership encourages their followers to participate in desired and ethical behaviors through promotion of ethical conduct. That is, ethical leaders can reward ethical behaviors and discipline harmful behaviors, due to their power to deliver punishments and rewards. In general, ethical leadership is likely to inhibit employees’ workplace cheating behavior, because through personal and promotion of ethical conduct, ethical leaders can clarify to their followers that what the appropriate behaviors should conduct at work. We thus hypothesize the following:

-

Hypothesis 1. Ethical leadership is negatively associated with workplace cheating behavior.

The Mediating Effect of Moral Identity

The relation between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior should be completely understood by testing the mediating role of moral identity. Prior work has suggested that moral identity plays an important mediating role in the relation between inputs and outcomes in a variety of settings (Bavik et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2016). Moral identity is on the base of social learning perspective, which believes that moral behavior could be learned and be the portion of an employee’s internalized social self-concept (Skubinn & Herzog, 2016). Employees with strong moral identity may believe that their colleagues deserve ethical treatment (Greenbaum et al., 2013; Liao et al., 2016). That is, employees who strongly embrace a moral identity may activate the more related identity-based knowledge to guide, inform, and regulate their behaviors (He et al., 2014). Also, prior work has suggested that employees with high moral identity may use self-regulatory mechanisms in conducting ethical behavior (Aquino et al., 2009). In contrast, employees with weak moral identity may not self-regulate their behavior, thereby displaying self-serving and harmful behavior to other colleagues. Indeed, previous research has conceptualized that moral identity is negatively related to workplace cheating behavior (Mitchell et al., 2018).

We argue that ethical leadership positively influences moral identity. Further, moral identity influences workplace cheating behavior. Consequently, we suggest that moral identity may mediate the relation between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior. Specifically, we examine the mediating role of moral identity in the relation between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior. Moral identity includes both internalization moral identity and symbolization moral identity (Aquino & Reed, 2002). Prior work has suggested that employees with high moral identity might report higher perceived obligations toward coworkers. That is, they are more likely to forgive transgressors and less likely to endorse inflicting harm on harmdoers (Reed & Aquino, 2003). Moral identity involves identifying a series of moral traits associated with individuals’ self-concept. However, it could be malleable to a specific mental image of what kind of ethical behavior should be conducted (Bavik et al., 2018; Cheryan & Bodenhausen, 2000). For instance, an individual is likely to construct his or her moral self-concept by learning from desirable moral models such as God, presidents, and religious leaders (Aquino & Reed, 2002; Bavik et al., 2018; Colby & Damon, 1992). Also, prior work has suggested that different identity aspects can be more or less activated by situational factors (e.g., Monin & Jordan, 2009). Thus, in this study, we expect that employees’ moral identity may be activated by ethical leadership, which is a crucial situational factor in the workplace. Ethical leadership consists of two components: moral person component and moral manager component (Brown et al., 2005). Moral person component suggested that ethical leaders should possess desirable characteristics and personal traits such as trustworthiness, honesty, and integrity. As a moral person, ethical leadership can affect a focal employee’s behavior via transformational means. Moral manager component suggested that ethical leaders can proactively affect focal employees’ ethical conduct through punishing harmful behavior and encouraging normative behavior (Brown & Treviño, 2006). In this study, we argue that ethical leadership affects focal employees’ moral identity in two ways. First, prior research has suggested that the motivation of moral identity derives from employees’ desire for self-consistency (Aquino & Reed, 2002). That is, an employee whose moral identity is self-important may behave relying on his or her understanding of what it means to be moral. Ethical leaders, who are prudent, trustworthy, and self-disciplined, emphasize the importance of being moral persons (Riggio et al., 2010). Accordingly, ethical leadership may affect employees’ moral identity. Based on social learning theory, ethical leadership may affect an employee’s moral identity in the workplace. This is because ethical leaders are credible and attractive moral persons who may hold and attract employees’ attention. Specifically, when ethical leaders manifest moral values (i.e., trustworthiness, caring, fairness, honesty, openness, and social responsiveness) (Brown et al., 2005), employees’ crucial moral traits, which are validated and conceptualized to activate network mapping onto their moral identity, will be echoed (Rupp et al., 2013). Also, by observing the moral values and beliefs demonstrated by ethical leaders, employees may identify their leaders’ moral values and participate in socially desirable behavior (Schaubroeck et al., 2012). Further, ethical leaders’ moral values can make great effect on employees’ self-concept, leading to assimilation of their leaders’ moral values, thereby improving employees’ moral identity (Sosik et al., 2014). Second, ethical leadership entails a moral manager dimension. Previous studies have suggested that ethical leadership may affect employees’ values by using rewards and punishments to prompt higher ethical standards (Treviño et al., 2003). Employees may pay close attention to ethical expectations and standards that are punished and rewarded by ethical leaders (Treviño, 1992). According to social learning theory, consequences such as punishments and rewards can prompt learning in an anticipatory way (Brown et al., 2005). This can help employees to understand the benefits of the moral conduct and the costs of immoral conduct. Consequently, ethical leaders can be viewed as social learning models, because they can discipline inappropriate conduct and reward moral conduct (Treviño et al., 2003). Previous research has suggested that moral identity, which makes up an individual’s social self-schema, may be suppressed or activated by contextual variables (Greenbaum et al., 2013). Accordingly, ethical leadership may play a crucial role in developing employees’ moral identity. Also, previous studies have provided evidence for the argument that ethical leadership is an important antecedent of moral identity (Bavik et al., 2018; Gerpott et al., 2019). This suggests that there may be a positive relationship between ethical leadership and moral identity.

To summarize, we suggest ethical leadership prompts moral identity, which in turn will influence workplace cheating behavior. Moral identity may mediate the relation between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior. Therefore, we argue that:

-

Hypothesis 2. Moral identity mediates the relation between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior.

The Moderating Effect of Leader-Follower Value Congruence

Prior work has suggested that leader-follower value congruence can be viewed as an important contextual moderator in leadership and ethical behavior literatures (Lee et al., 2017). Social learning theory also explicitly assumes high value congruence, because an individual may internalize the leader’s values and emulate the leader’s ethical behavior when the follower and leader have similar interests, goals, and guiding principles concerning actions and decisions. By extension, the relationship between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior via moral identity, should be strengthened when value congruence is relatively high. We expect that ethical leadership may be effectively mobilized to prompt moral identity and inhibit workplace cheating behavior under high value congruence than under low value congruence for two reasons.

Drawing on the social learning framework, we argue that leader-follower value congruence is likely to prompt followers’ social learning processes, because they perceive ethical leadership as a favorable role model, which can prompt the development of their moral identity and subsequent ethical behavior. Followers with high value congruence with the leader may promptly adapt to the leader’s beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors (Ostroff et al., 2005), thereby helping the follower develop his or her moral identity. Specifically, when the leader and the follower have similar interests, goals, and principles, the follower is more likely to see ethical leadership as a credible and attractive role model, so he or she will positively evaluate, identify, and internalize the leader’s role model such as integrity, honesty, and trustworthiness. Aquino and Reed (2002) argued that employees may view moral traits as being necessary to their self-concept, and certain moral traits can activate an employee’s moral identity.

The above analysis suggests that the relation between leadership and followers’ moral identity varies as a function of value congruence: Those with higher levels of leader-follower value congruence generally respond more favorably to leaders’ influence, because they are more likely to appreciate their leaders’ positive attitudes, identify their leaders’ moral values, and act according to their subordinate role. Indeed, prior wok has examined the degree to which the leader–follower value congruence moderates the influence of leadership. For example, according to Lee et al. (2017), different followers may respond to the same leadership style differently, depending on the perceived values similarity between the leader and the follower. Also, research along this line of inquiry has suggested that a supervisor may not become a leader for the followers without providing support for the followers’ feelings of self-worth and self-concept (Babalola et al., 2018). This means that followers may be distinct in their interpretations of and reactions to identical leadership behaviors. Thus, followers who hold high value congruence with the leader may respond more strongly and positively to the influence of ethical leadership by shaping higher levels of moral identity and engaging in socially desirable behavior. Specially, when their leader manifests moral values, encourage normative behavior, and punish harmful behavior, employees with high value congruence with the leader may be more sensitive to the stimulation, to be willing to emulate the leader’s moral values and shape their moral identity, and may be less likely to engage in workplace cheating behavior.

In contrast, when the leader-follower value congruence is low, the motivational tendency to leverage moral identity associated with the ethical leadership is constrained, because the follower considers ethical leadership as simply dogmatic or impractical (Lee et al., 2017). Also, according to Brown and Treviño (2009), discrepancy in the interests, goals, characteristics, and principles will inhibit the development of the followers’ moral identity.

The above reasoning suggests that leader-follower value congruence plays a moderating role in the relation between ethical leadership and moral identity. To summarize, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 3. The relation between ethical leadership and moral identity may be moderated by leader-follower value congruence. The higher the leader-follower value congruence, the more positive the relation.

So far, we have argued that moral identity mediated the relation between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior, and leader-follower value congruence moderated the relation between ethical leadership and moral identity. Based on the notion that leader-follower value congruence plays a moderating role in the relation between ethical leadership and moral identity, and considering that moral identity related positively to workplace cheating behavior, it is logical to argue that leader-follower value congruence is likely to moderate the strength of the mediating role of moral identity in the relationship between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior—thereby demonstrating a pattern of moderated mediation model (Edwards & Lambert, 2007). That is, a weaker relation between ethical leadership and moral identity may emerge among employees who has low value congruence with the leader, and the indirect influence of ethical leadership on workplace cheating behavior through moral identity may be weaker. Specifically, when employees, who have high value congruence with the leader, react to ethical leadership more sensitively by shaping their moral identity, the indirect influence of ethical leadership on workplace cheating behavior should be stronger. Hence, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 4. The strength of the mediated relationship between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior via moral identity will depend on the leader–follower value congruence; the indirect and total effects of ethical leadership on workplace cheating behavior will be weaker when the leader-follower value congruence is low.

Method

Sample and Procedure

Data were collected from employees and their direct supervisors in different Chinese companies involved in manufacturing, technology, and telecommunication. One of the authors contacted the HR managers and introduced our study. The questionnaires were distributed to the subordinates. Participation was voluntary, and the subordinates were assured that their individual responses would only be used for academic research. In order to preserve their anonymity, all identifying information would be removed.

We collected data from the employees and their direct supervisors. At time 1, 427 employees were required to report their demographic characteristics, ethical leadership, and leader-follower value congruence. A total of 332 employees completed the survey, resulting in response rates of 77.75%. At time 2, after approximately one month, we asked employees who had finished first-wave questionnaires to assess moral identity. Two hundred and ninety employees completed their surveys, resulting in response rates of 87.34%. Finally, one month later (T3), we distributed the questionnaires to the 73 supervisors of the 290 subordinates who had finished the T1 and T2 surveys to assess employees’ workplace cheating behavior. A total of 251 pairs of questionnaires were returned. After dropping questionnaires with incomplete data, our final sample contained 243 supervisor–subordinate dyads, giving us a response rate of 83.79%. Of these employees, 9.72% had a master degree or above, and 45.00% of the employees were female. In addition, the mean age was 33.17 years (s. d. = 6.42).

Measures

We used back-translation procedure (Brislin, 1980) to translate the survey items from English to Chinese. That is, two scholars translated the survey items from English to Chinese. Then another scholar translated the survey items back to English and made some modifications. Response to all the measures were made on a five Likert-type response options (“1” = strongly disagree; “2” = disagree; “3” = not sure; “4” = agree; “5” = strongly agree). All the items of the four variables are reported in “Appendix 1”.

Ethical Leadership

The ten-item scale instrument developed by Brown et al. (2005) were employed to assess ethical leadership. A sample items is “My leader sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics”. The Cronbach’s alpha for ethical leadership is .87.

Workplace Cheating Behavior

Workplace cheating behavior was measured employing a seven-item scale developed by Mitchell et al. (2018). A sample item is “Exaggerated work hours to look more productive”. The Cronbach’s alpha for ethical leadership is .75.

Moral Identity

We measured moral identity employing five-item internalization subscale of Aquino and Reed’s (2002) moral identity, which is also applied by Skarlicki et al. (2016). Employees were asked to imagine an individual who has nine moral traits such as “caring”, “fair”, “compassionate”, “honest”, and to indicate the degree of which possessing these traits is crucial to the sense of themselves. The Cronbach’s alpha for ethical leadership is .74.

Leader-Follower Value Congruence

Leader-follower value congruence was measured using Cable and Derue’s (2002) three-item scale and applied by Lee et al. (2017). A sample is “My immediate manager’s work values provide a good fit with the things that I value in a job”. The Cronbach’s alpha for ethical leadership is .70.

Control Variables

In testing the hypotheses, we controlled several variables. Age, gender, and educational level were controlled, because they can affect employees’ workplace cheating behaviors (Mitchell et al., 2018). Specifically, according to Jackson et al. (2002), the female employees may experience more guilt than the male employees if they cheat. Thus, the female employees may be less likely to cheat than the male employees. Furthermore, according to Whitley (1998), the younger and lower educational level employees may be less mature than the older and higher educational level employees, and thus, they will be more likely to participate in workplace cheating behavior. Age was self-reported in years; gender was dummy coded (male = 1, female = 0). Additionally, we controlled individual employees’ educational level with four options (4 = master or above; 3 = bachelor; 2 = junior college; 1 = high school or below).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

As shown in Table 1, ethical leadership was positively related to employees’ moral identity (r = .17, p < .01), negatively associated with workplace cheating behavior (r = −.18, p < .01), and not related to leader-follower value congruence (r = .02, n. s.). Employees’ moral identity was negatively associated with workplace cheating behavior (r = −.38, p < .01), and not related to leader-follower value congruence (r = −.12, n. s.). In addition, leader-follower value congruence is not positively related to workplace cheating behavior (r = .04, n. s.). Thus, our hypotheses were preliminarily supported.

Construct Validity

Before testing the hypotheses, the construct validity of these variables was examined (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). We employed the AMOS software to conduct a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to ensure the construct distinctiveness of the four variables. According to Little et al. (2002), we randomly created three parcels for ethical leadership, moral identity, leader-follower value congruence, and workplace cheating behavior. This procedure is used because it can produce more stable parameter estimates and minimize sharing variance of the indicators of each construct (Aryee et al., 2014; Robert et al., 2000). The results demonstrated that the four-factor model provided a good fit (χ2 = 93.07, df = 48, CFI = .94, TLI = .92, RMSEA = .062). In addition, the four-factor model is compared to a model that contained one single factor (χ2 = 526.86, df = 54, CFI = .40, TLI = .26, RMSEA = .190). The results demonstrated that the four-factor model showed a better fit than the one-factor model (χ2difference = 433.79, df = 10).

Hypothesis Testing

A bootstrapping-based test using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013) was conducted to test Hypothesis 1, 2 and 3. As shown in Model 3, ethical leadership was negatively related to workplace cheating(b = −.17, P = .01, 95% CIs [−.286, −.051]), which supported Hypothesis 1. The results supported H2 (The mediating role of moral identity in the relationship between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior). Hypothesis 2 proposes that moral identity plays a mediating role in the relation between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior. As shown in Model 1, ethical leadership was negatively related to moral identity (b = −.23, P = .00, 95% CIs [−.092, −.373]). Additionally, Model 4 demonstrates that moral identity was negatively related to workplace cheating behavior (b = −.30, P = .00, 95% CIs [−.397, −.198]), and the relations between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior was non-significant (b = −.10, P = .08, 95% CIs [−.211, .013]) when moral identity was included in the model. Results further showed that ethical leadership was associated with decreased workplace cheating behavior, mediated by moral identity (indirect effect = −.069, SE = .03, 95% CI = −.129 to −.029; direct effect = −.099, SE = .06, 95% CI = −.211 to .013; total effect = −.169, SE = .06, 95% CI = −.286 to −.051), and thus supporting Hypotheses 2.

Furthermore, Hypothesis 3 proposes that leader-follower value congruence plays a moderating role in the relationship between ethical leadership and moral identity. As shown in Table 2, in order to examine Hypothesis 3, we examined the interactive effect of ethical leadership and leader-follower value congruence on moral identity. The results showed that the interaction between ethical leadership and leader-follower value congruence was positively related to moral identity (Model 2: b = .38, p = .00, 95% CIs [.168, .582]). The interactive effect of ethical leadership and leader-follower value congruence on moral identity were plotted using Stone and Hollenbeck’s (1989) procedure. That is, the slopes were computed using one standard deviation below and above the mean of leader-follower value congruence. Figure 2 shows that ethical leadership is more significantly and positively associated with moral identity when leader-follower value congruence is high rather than low. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

In addition, the methods of Hayes (2013) were utilized to test Hypothesis 4 in an integrative fashion at one standard deviation above and below the mean of leader-follower value congruence. As shown in Table 3, when leader-follower value congruence was high, the mediating role of moral identity was not significant (conditional indirect effect = −.01, SE = .02, 95% CI = −.06 to .03). However, when leader-follower value congruence was low, the mediating role of moral identity was significant (conditional indirect effect = .14, SE = .03, 95% CI = −.21 to −.08). In addition, the index of moderated mediation was significant (Index = −.13, SE = .03, 95% CI = −.21 to −.07), providing further support for Hypothesis 4. That is, ethical leadership is generally related to workplace cheating behavior, the influence is stronger when leader-follower congruence is high but dissipates when leader-follower congruence is low.

Discussion

Based on social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), an integrated theoretical framework was presented to delineate how ethical leadership impacts workplace cheating behavior. As previously discussed, ethical leadership is negatively associated with workplace cheating behavior. Results demonstrated that moral identity played a mediating role in the relationship between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior, that leader-follower value congruence moderated the association between ethical leadership and moral identity, and that the indirect influence of ethical leadership on workplace cheating behavior (via moral identity) was weaker when leader-follower value congruence was high rather than low.

Theoretical Implications

In this study, we make several theoretical contributions. First, this study enhances understanding of the role of leadership in the influence of workplace cheating behavior. Past research concerning the antecedents of workplace cheating behavior has mainly focused on COVID-19, temptation, underdog expectation, customer mistreatment, peer influence and performance pressure (Hillebrandt & Annika, 2022; Pate, 2018; Loi et al., 2021; Men et al., 2021; Mitchell et al., 2018; Malesky et al., 2022). Consequently, the influence of leadership on workplace cheating behavior has generally been left unexplored. Our study addressed this research gap by employing a temporally lagged field research design to offer empirical evidence about the inhibiting effect of ethical leadership on workplace cheating behavior. Our research also responds to Mitchell et al.’ (2018) call for the examination of the effect of ethical leadership on cheating behavior, we aim to examine whether and how ethical leadership affects cheating behavior. Specifically, drawing on social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), we examine the relation between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior.

Second, we examine the mediating mechanism through which ethical leadership affects workplace cheating behavior. Indeed, prior work has conceptualized that ethical leadership has critical implications for workplace cheating behavior (Mitchell et al., 2018), however, little attention has been paid to systematically testing how ethical leadership affects workplace cheating behavior. Our study addressed this research gap and demonstrated that the moral identity played a crucial mediating role in explaining the influence of ethical leadership on workplace cheating behavior. The relationship between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior may be mediated by moral identity. Specifically, we argue ethical leadership may influence workplace cheating behavior via moral identity because moral values such as fairness, trustworthiness, honesty, openness, caring, and social responsiveness are valued (Blader & Tyler, 2009), and because it signals that moral conduct is rewarded and inappropriate conduct is punished. Consequently, ethical leadership can shape employees’ moral identity, thereby negatively influencing workplace cheating behavior.

Third, this study demonstrated that the association between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior via moral identity was conditional on leader-follower value congruence. Specially, in a high leader-follower value congruence, ethical leadership has greater effect on moral identity. Consequently, another important contribution is to identify a crucial important boundary condition for the impact of ethical leadership on workplace cheating behavior relation. As a result, we not only theoretically identified the interactive effect of ethical leadership and leader-follower value congruence on moral identity, but also empirically examined the boundary condition—leader-follower value congruence in the relation between ethical leadership and moral identity. This finding aligns well with previous research showing that leader-follower value congruence played an important moderating role in the literature on leadership (Cheng et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2017).

In addition, using a moderated mediation framework, we suggest that the mediation-chain relation is likely to be more complex than previously understood, in which the relation may vary with leader-follower value congruence. Specifically, by adopting Hayes’s (2013) moderated-mediation approach, our study indicated that the mediating role of moral identity in the association between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior may be significantly weaker or stronger, relying on leader-follower value congruence. Specifically, the mediating role of moral identity in the relationship between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior were stronger for followers with higher value congruence with the leader.

Practical Implications

Our study has several clear managerial implications. First, leaders should be encouraged to practice ethical role modeling, demonstrate high ethical standards, and participate in concurrent punishment and reward programs (Lee et al., 2017), because these efforts may be beneficial to shape employees’ moral identity. An employee with high moral identity may be less likely to participate in workplace cheating behavior. Therefore, an organization should improve the level of ethical leadership among managers. For example, an organization should employ selection tools to evaluate the ethicality of leaders and select leaders with ethical potential. Also, an organization should offer training programs to nurture leaders’ ethical sensitivity, foster an ethical culture, and establish informal and formal mentoring programs (Bavik et al., 2018).

Second, our results show that moral identity mediates the association between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior. Therefore, managers can take steps to improve employees’ moral identity. For example, managers should reward and publish behaviors that are related to moral identity, which in turn will foster the development of moral identity of employees (Reynolds & Ceranic, 2007). Additionally, managers can employ employees with high moral identity, because they may be less likely to engage in workplace cheating behavior (Reynolds & Ceranic, 2007).

Third, our study suggests that when the values of employees are in line with their leaders, ethical leadership will be more effective and salient (Lee et al., 2017). Thus, organizations should emphasize value congruence between leaders and followers to prompt followers’ moral decisions and behaviors. For example, organizations should encourage leaders to share their personal ethical values with the follower (Lee et al., 2017), because this can help the follower to internalize the leader’s values and emulate the leader’s ethical behavior. Also, employees should proactively interact and communicate with their ethical leaders to understand their leaders’ moral values and ideals.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

There are several potential limitations. First, the influence of ethical leadership on workplace cheating behavior was mediated by moral identity. However, other mediators are likely to exist and can help to explain this process. For example, anger is also one of the important ingredients for workplace cheating behavior (Mitchell et al., 2018). Prior work has suggested that supervisory behaviors can affect followers’ emotions (e.g., anger and anxiety), which in turn is negatively related to follower workplace cheating (Mawritz et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2018). Future research should examine the mediating role of anger in the relation between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior.

Second, the design of the study may limit our ability to confer cause-effect relation. This study could not necessarily indicate that ethical leadership is the cause of reduced cheating behavior in the workplace, as one may argue that employees with high cheating behavior would discourage the leader to engage in more ethical behaviors. Indeed, there is increasing support for the idea that followers’ behaviors also can influence how leaders act toward their employees (e.g., Keem et al., 2018). Future research should employ longitudinal or field-experimental research designs to examine the causality of the relation examined in this study.

Third, according to Schwartz and Sagie (2000), personal values may be quite different in nature. For example, self-transcendence and self-enhancement are two opposite dimensions of values, and values of self-transcendence are more closely related to morality than values of self-enhancement (Schwartz & Sagie, 2000). Hence, future research should discuss the possibility that different value dimensions may have differential effects for enhancing or reducing the impact of ethical leadership on followers’ moral identity.

Fourth, leader-follower value congruence was measured using Cable and Derue’s (2002) three-item scale. However, this approach has captured only followers’ general perceptions of values congruence with the leader (Brown & Treviño, 2009). Future research can use polynomial regression to examine leader-follower value congruence (Kang et al., 2014).

Fifth, cheating behavior was assessed by supervisors. Other-reports of cheating behavior may mitigate some of the key concerns over self-report cheating behavior such as underreporting due to fear of being caught common method bias. However, there are also disadvantages to other-reports of cheating behavior (Zaal et al., 2019). For example, supervisors may not have adequate opportunity to observe employees engaging in cheating behavior. Future research can use both self-reported and other-reports of cheating behavior.

Sixth, in our study, we just control demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, and educational level). However, we did not control other variables. Future research can control other variables such as interests and the change of the moral identity, because these variables may affect employees’ workplace cheating behaviors.

In addition, other plausible moderators were not examined in the relationship between ethical leadership and workplace cheating behavior. As Mitchell et al. (2018) argued, performance pressure may be one of the most critical factors for workplace cheating behavior. If individuals experience high levels of performance pressure, they are more likely to improve states relevant to a requirement for self-protection, which in turn will result in workplace cheating behavior. Future research should examine this moderating relation to fully understand why and how ethical leadership affects workplace cheating behavior.

Conclusion

Given the potentially devastating consequences of cheating behavior and increasing demands for ethical standards in the workplace, the importance of business ethics among leaders is obvious. Our study demonstrated that ethical leadership may influence employees’ moral identity, thereby inhibiting their workplace cheating behavior. Consequently, our study advances our understanding of the importance of ethical leadership by demonstrating its positive effects. In addition, our study considered the boundary conditions surrounding the effects of ethical leadership. Specifically, leader-follower value congruence can play a moderating role, whereby it can strengthen the association between ethical leadership and moral identity.

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Appelbaum, S. H., Iaconi, G. D., & Matousek, A. (2007). Positive and negative deviant workplace behaviors: Causes, impacts, and solutions. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 7(5), 586–598. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720700710827176

Aquino, K., & Reed, A. I. I. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423–1440. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.83.6.1423

Aquino, K., Freeman, D., Reed, A., Lim, V. K. G., & Felps, W. (2009). Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: The interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015406

Aryee, S., Walumbwa, F. O., Mondejar, R., & Chu, C. W. L. (2014). Core self-evaluations and employee voice behavior. Journal of Management, 43(3), 946–966. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314546192

Avey, J. B., Wernsing, T. S., & Palanski, M. E. (2012). Exploring the process of ethical leadership: The mediating role of employee voice and psychological ownership. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1298-2

Babalola, M. T., Stouten, J., Euwema, M. C., & Ovadje, F. (2018). The relation between ethical leadership and workplace conflicts: The mediating role of employee resolution efficacy. Journal of Management, 44(5), 2037–2063. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316638163

Ballantine, J. A., Guo, X., & Larres, P. (2018). Can future managers and business executives be influenced to behave more ethically in the workplace? The impact of approaches to learning on business students’ cheating behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 149(1), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3039-4

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall.

Bavik, Y. L., Tang, P. M., Shao, R., & Lam, L. W. (2018). Ethical leadership and employee knowledge sharing: Exploring dual-mediation paths. Leadership Quarterly, 29(2), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.05.006

Blader, S. L., & Tyler, T. R. (2009). Testing and extending the group engagement model: Linkages between social identity, procedural justice, economic outcomes, and extrarole behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013935

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (pp. 389–444). Allyn & Bacon.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2009). Leader-follower values congruence: Are socialized charismatic leaders better able to achieve it? Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 478–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014069

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002

Byun, G., Karau, S. J., Dai, Y., & Lee, S. (2018). A three-level examination of the cascading effects of ethical leadership on employee outcomes: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Business Research, 88, 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.004

Cable, D. M., & DeRue, D. S. (2002). The construct, convergent, and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.87.5.875

Cheng, K., Wei, F., & Lin, Y. H. (2019). The trickle-down effect of responsible leadership on unethical pro-organizational behavior: The moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Journal of Business Research, 102, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.04.044

Cheryan, S., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2000). When positive stereotypes threaten intellectual performance: The psychological hazards of model minority status. Psychological Science, 11(5), 399–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00277

Colby, A., & Damon, W. (1992). Some do care: Contemporary lives of moral commitment. Free Press.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1

Gerpott, F. H., Van Quaquebeke, N., Schlamp, S., & Voelpel, S. C. (2019). An identity perspective on ethical leadership to explain organizational citizenship behavior: The interplay of follower moral identity and leader group prototypicality. Journal of Business Ethics, 156(4), 1063–1078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3625-0

Goman, C. K. (2013). The high cost of workplace deception. Troy Media. Retrieved from http://www.troymedia.com/2013/06/05/the-high-cost-of-workplace-deception.

Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., Mayer, D. M., & Priesemuth, M. (2013). To act out, to withdraw, or to constructively resist? Employees reactions to supervisor abuse of customers and the moderating role of employee moral identity. Human Relations, 66(7), 925–950. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713482992

Greenbaum, R. L., Quade, M. J., & Bonner, J. (2015). Why do leaders practice amoral management? A conceptual investigation of the impediments to ethical leadership. Organizational Psychology Review, 5(1), 26–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386614533587

Groves, K. S. (2014). Examining leader-follower congruence of social responsibility values in transformational leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21(3), 227–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051813498420

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

He, H., Zhu, W., & Zheng, X. (2014). Procedural justice and employee engagement: Roles of organizational identification and moral identity centrality. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(4), 681–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1774-3

Hillebrandt, A., & Annika, L. J. (2022). How COVID-19 can promote workplace cheating behavior via employee anxiety and self-interest: And how prosocial messages may overcome this effect. Journal of Organizational Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2612

Huang, L., & Paterson, T. A. (2017). Group ethical voice: Influence of ethical leadership and impact on ethical performance. Journal of Management, 43(4), 1157–1184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314546195

Jackson, C. J., Levine, S. Z., Furnham, A., & Burr, N. (2002). Predictors of cheating behavior at a university: A lesson from the psychology of work. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(5), 1031–1046. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00254.x

Jung, D. I., & Avolio, B. J. (2000). Opening the black box: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of trust and value congruence on transformational and transactional leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(8), 949–964. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1379(200012)21:83.0.CO;2-F

Kang, S.-W., Byun, G., & Park, H.-J. (2014). Leader-follower value congruence in social responsibility and ethical satisfaction: A polynomial regression analysis. Psychological Reports: Employment Psychology and Marketing, 115(3), 725–740. https://doi.org/10.2466/01.14.PR0.115c33z9

Keem, S., Shalley, C. E., Kim, E., & Jeong, I. (2018). Are creative individuals’ bad apples? A dual pathway model of unethical behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(4), 416–431. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000290

Lam, L. W., Loi, R., Chan, K. W., & Liu, Y. (2016). Voice more and stay longer: How ethical leaders influence employee voice and exit intentions. Business Ethics Quarterly, 26(3), 277–300. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2016.30

Lee, D., Choi, Y., Youn, S., & Chun, J. U. (2017). Ethical leadership and employee moral voice: The mediating role of moral efficacy and the moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2689-y

Liao, Y., Liu, X. Y., Kwan, H. K., & Tian, Q. T. (2016). Effects of sexual harassment on employees’ family undermining: Social cognitive and behavioral plasticity perspectives. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33(4), 959–979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-016-9467-y

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Liao, C., & Meuser, J. D. (2014). Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1434–1452. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0034

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

Loi, T. I., Feng, Z. Y., Kuhn, K. M., & Tripp, T. M. (2021). When and how underdog expectations promote cheating behavior: The roles of need fulfillment and general self-efficacy. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04976-0

Luan, K., Lv, M., & Zheng, H. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and cheating behavior: The mediating effects of organizational identification and perceived supervisor moral decoupling. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 768293–768293. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.768293

Malesky, A., Grist, C., Poovey, K., & Dennis, N. (2022). The effects of peer influence, honor codes, and personality traits on cheating behavior in a university setting. Ethics & Behavior, 32(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2020.1869006

Mawritz, M. B., Folger, R., & Latham, G. P. (2014). Supervisors' exceedingly difficult goals and abusive supervision: The mediating effects of hindrance stress, anger, and anxiety. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(3), 358–372. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1879

Mayer, D. M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R. L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 151–171. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.0276

Men, C. H., Fong, P. S. W., Huo, W. W., Zhong, J., Jia, R. Q., & Luo, J. L. (2020). Ethical leadership and knowledge hiding: A moderated mediation model of psychological safety and mastery climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 166(3), 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4027-7

Men, C. H., Huo, W. W., & Wang, J. (2021). Who will pay for customers' fault? Workplace cheating behavior, interpersonal conflict and traditionality. Personnel Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-05-2020-0309

Mitchell, M. S., Baer, M. D., Ambrose, M. L., Folger, R., & Palmer, N. F. (2018). Cheating under pressure: A self-protection model of workplace cheating behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000254

Monin, B., & Jordan, A. H. (2009). The dynamic moral self: A social psychological perspective. In D. Narvaez & D. K. Lapsley (Eds.), Personality, identity, and character: Explorations in moral psychology (pp. 341–354). Cambridge University Press.

Ogunfowora, B. (2014). It's all a matter of consensus: Leader role modeling strength as a moderator of the links between ethical leadership and employee outcomes. Human Relations, 67(12), 1467–1490. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726714521646

Ostroff, C., Shin, Y., & Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Multiple perspectives of congruence: Relationships between value congruence and employee attitudes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(6), 591–623. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.333

Pate, J. (2018). Temptation and cheating behavior: Experimental evidence. Journal of Economic Psychology, 67, 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2018.05.006

Paterson, T. A., & Huang, L. (2019). Am I expected to be ethical? A role-definition perspective of ethical leadership and unethical behavior. Journal of Management, 45(7), 2837–2860. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318771166

Pfeffer, J. (1983). Organizational demography. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 5, pp. 299–357). JAI.

PricewaterhouseCoopers, L. L. P. (2014). February 25 global economic crime survey. Retrieved from http://www.pwc.com/us/crimsurvey.

Qin, X., Huang, M., Hu, Q., Schminke, M., & Ju, D. (2018). Ethical leadership, but toward whom? How moral identity congruence shapes the ethical treatment of employees. Human Relations, 71(8), 1120–1149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717734905

Quade, M. J., Perry, S. J., & Hunter, E. M. (2017). Boundary conditions of ethical leadership: Exploring supervisor-induced and job hindrance stress as potential inhibitors. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(6), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3771-4

Reed, A. I. I., & Aquino, K. F. (2003). Moral identity and the expanding circle of moral regard towards out-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1270–1286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1270

Reynolds, S. J., & Ceranic, T. L. (2007). The effects of moral judgment and moral identity on moral behavior: An empirical examination of the moral individual. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1610–1624. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1610

Riggio, R. E., Zhu, W., Regina, C., & Maroosis, J. A. (2010). Virtue-based measurement of ethical leadership: The leadership virtues questionnaire. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 62(4), 235–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022286

Robert, C., Probst, T. M., Martocchio, J. J., Drasgow, F., & Lawler, J. J. (2000). Empowerment and continuous improvement in the United States, Mexico, Poland, and India: Predicting fit on the basis of dimensions of power distance and individualism. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 643–658. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.85.5.643

Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Thornton, M. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Personnel Psychology, 66(4), 895–933. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12030

Schaubroeck, J. M., Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., Kozlowski, S. W. J., Lord, R. G., Treviño, L. K., & Peng, A. C. (2012). Embedding ethical leadership within and across organizational levels. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1053–1078. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0064

Schwartz, S. H., & Sagie, G. (2000). Value consensus and importance: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(4), 465–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022100031004003

Shin, S. J., & Zhou, J. (2003). Transformational leadership, conservation, and creativity: Evidence from Korea. Academy of Management Journal, 46(6), 703–714. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040662

Skarlicki, D. P., van Jaarsveld, D. D., Shao, R., Song, Y. H., & Wang, M. (2016). Extending the multifoci perspective: The role of supervisor justice and moral identity in the relationship between customer justice and customer-directed sabotage. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(1), 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000034

Skubinn, R., & Herzog, L. (2016). Internalized moral identity in ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(2), 249–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2369-3

Sosik, J. J., Chun, J. U., & Zhu, W. (2014). Hang on to your ego: The moderating role of leader narcissism on relationships between leader charisma and follower psychological empowerment and moral identity. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1651-0

Stone, E. F., & Hollenbeck, J. R. (1989). Clarifying some controversial issues surrounding statistical procedures of detecting moderator variables: Empirical evidence and related matters. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.74.1.3

Treviño, L. K. (1992). The social effects of punishment in organizations: A justice perspective. Academy of Management Review, 17(4), 647–676. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1992.4279054

Treviño, L. K., Brown, M., & Hartman, L. P. (2003). A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Human Relations, 56(1), 5–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726703056001448

Walumbwa, F. O., Hartnell, C. A., & Misati, E. (2017). Does ethical leadership enhance group learning behavior? Examining the mediating influence of group ethical conduct, justice climate, and peer justice. Journal of Business Research, 72, 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.11.013

Wang, Z., Xing, L., Xu, H., & Hannah, S. T. (2019). Not all followers socially learn from ethical leaders: The roles of followers’ moral identity and leader identification in the ethical leadership process. Journal of Business Ethics, 170(3), 449–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04353-y

Whitley, B. E. (1998). Factors associated with cheating among college students: A review. Research in Higher Education, 39(3), 235–274. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018724900565

Zaal, R. O. S., Jeurissen, R. J. M., & Groenland, E. A. G. (2019). Organizational architecture, ethical culture, and perceived unethical behavior towards customers: Evidence from wholesale banking. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(3), 825–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3752-7

Acknowledgements

China Postdoctoral Science Foundation 2019 M662391.

Humanity and Social Science Youth foundation of Ministry of Education of China 20YJC630103.

Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province ZR201911090224.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest in our manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Ethical Leadership

-

1.

My leader listens to what employees have to say.

-

2.

My leader disciplines employees who violate ethical standards.

-

3.

My leader conducts his/her personal life in an ethical manner.

-

4.

My leader has the best interests of employees in mind.

-

5.

My leader makes fair and balanced decisions.

-

6.

My leader can be trusted.

-

7.

My leader discusses business ethics or values with employees.

-

8.

My leader sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics.

-

9.

My leader defines success not just by results but also the way that they are obtained.

-

10.

When making decisions, my leader asks “what is the right thing to do?”.

Moral identity

Listed below are some characteristics that may describe a person [caring, compassionate, fair, friendly, generous, helpful, hardworking, honest, and kind]. The person with these characteristics could be you or it could be someone else.

-

1.

It would make me feel good to be a person who has these characteristics.

-

2.

Being someone who has these characteristics is an important part of who I am.

-

3.

I would be happy to be a person who has these characteristics.

-

4.

Having these characteristics is not really important to me.

-

5.

I strongly desire to have these characteristics.

Leader-follower value congruence

-

1.

The things that I value in a job are very similar to the things that my immediate manager values.

-

2.

My work values match my immediate manager’s work values.

-

3.

My immediate manager’s work values provide a good fit with the things that I value in a job.

Cheating behavior

-

1.

This employee misrepresented work activity to make it look as though he/she has been productive.

-

2.

This employee made it look like he/she was working when you were not.

-

3.

This employee made up work activity to look better.

-

4.

This employee exaggerated work hours to look more productive.

-

5.

This employee came in late and didn’t report it.

-

6.

This employee made up an excuse to avoid being in trouble for not completing work.

-

7.

This employee lied about the reason he/she was absent.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yue, L., Men, C. & Ci, X. Linking perceived ethical leadership to workplace cheating behavior: A moderated mediation model of moral identity and leader-follower value congruence. Curr Psychol 42, 22265–22277 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03279-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03279-5