Abstract

The psychological phenomenon of Parental Burnout (PB) results from an imbalance between continuous exposure to chronic parenting stress and available coping resources. The study’s aim was to examine relationships between mothers’ perceived burden of treatment and PB, and their ability to utilize emotion work (EW) as a psychological coping resource. Ninety-eight Israeli mothers (46 had children with special needs with disabilities—W-SND, and 52 had children without special needs—WO-SN) completed questionnaires assessing their perception of burden of treatment, EW and PB. According to the findings, mothers of children W-SND reported significantly higher PB, a higher perceived burden of treatment and deeper EW than mothers of children WO-SN. Additionally, among all the mothers, a positive significant correlation was found between perceived burden of treatment and PB, while among mothers of children W-SND, positive correlations were found between their perceived burden of treatment and deep EW, and between deep EW and PB. These findings suggest that among mothers of children W-SND, PB is related to their perception of the burden of treatment and to performing deep EW. Additional psychological, cultural and environmental factors should be investigated, in order to gain new perspectives regarding PB as a psychological phenomenon that affects parenting and the ability to utilize coping mechanisms for mothers generally and for mothers of children W-SND especially.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Burnout syndrome is defined as a psychological phenomenon, involving a state of emotional, mental and physical exhaustion caused by continuous exposure to chronic stress. Burnout is inherent in professions and occupations, especially those that involve activities which require intensive communication and close-contact within intense environments, while providing assistance to people (Bezliudnyi et al., 2019). Burned-out individuals manifest psychosomatic problems (i.e., weakness/insomnia), psychological and emotional problems (i.e., anxiety/depression), attitude problems (i.e., hostility/apathy/distrust) and behavioral problems (i.e., aggressiveness/cynicism/ inefficacy/ irritability/isolation), among other problems (Adriaenssens et al., 2015; Lastovkova et al., 2018). Previous studies show that depression and burnout are strongly correlated but it is recommended to consider burnout as a distinctive construct (Bianchi et al., 2015; Schonfeld & Bianchi, 2016). Recently, researchers have recognized that the psychological phenomenon of burnout includes a specific syndrome, Parental Burnout (PB), which stems from the parental role (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018). PB and depressive symptoms have several common consequences, yet the construct of PB is distinguished from depression (Mikolajczak et al., 2020).

Parental Burnout

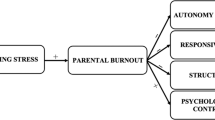

PB is created due to an imbalance between risk factors, such as irregular and unusual pressures following parenting, ongoing demands, difficulties, family stress – and protective factors, such as the availability and quantity of coping resources.

PB consists of four main dimensions: (1) physical and emotional exhaustion in the parental-role (chronic-fatigue); (2) emotional distancing from the child (parents focus on addressing only the basic needs of his child); (3) saturation from the parental-role (an inability to cope with and enjoy the parental role); and (4) a contrast with previous parental-self (present parenthood compared to the past) (Mikolajczak et al., 2018). Accordingly, burnout may result in parents becoming emotionally distant from their children and gradually becoming less involved and limited in practical aspects (Mikolajczak et al., 2018; Van Bakel et al., 2018). According to estimates from recent studies in the US, about three and a half million parents experience PB (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018). However, previous research has focused on PB among parents of healthy children while few studies were conducted among parents of children with special needs with disabilities (W-SND – children with disabilities who require long-term treatment, Carroll, 2013). We hypothesize that mothers of children W-SND will report higher PB than mothers of children WO-SN.

Caregiver Burden of Treatment as a Risk Factor

Parents of children W-SND need to deal with the emotional, mental, economic and social pressures associated with their child’s long-term care requirements which can cause caregiver-burden (Bedard et al., 2001; Gérain & Zech, 2018). This high sense of caregiver-burden for a child W-SND can lead to increased PB which affects family relationships, reduces family activities, and impairs the quality of the parents’ marriage; indeed, parents of children with chronic illnesses have reported neglecting their physical and emotional needs and developing higher burnout (Gérain & Zech, 2018; Lindström et al., 2010; Vinayak & Dhanoa, 2017). These scarce studies which have examined the risk of burnout among parents of children with chronic illness have reported that the parents are at higher risk for PB, as compared to parents of healthy children.

Since the type of disability and how severely it affects the child’s independence dictates the degree of daily support required from the primary caregiver, this affects the burden of parental care (Gardiner, & Iarocci, 2012). It has been found that parents of children with severe disabilities, compared to those with mild disabilities, have perceived their parental role as being responsible for the intensive care of their child including many therapeutic tasks (Gardiner & Iarocci, 2012). Parents have reported difficulties in bearing this therapeutic burden when their child’s disability is associated with impaired functioning, particularly in the areas of communication and behavior. Moreover, it was found that parents of children with mental disabilities reported a higher emotional care burden compared to parents of children with physical or sensory developmental disabilities (Alfasi Henley, 2016). This sense of the burden of care consequently forces parents to deal with a variety of unique difficulties that harm their physical health and mental well-being. Seltzer et al. (2009) found that parents of adolescent children with disabilities had higher levels of stress, negative emotion, physical symptoms, and cortisol levels than parents of children without disabilities. However, assistance in the form of internal and external resources can provide protective support factors against burnout. For example, a recent study found that self-compassion, emotional intelligence, external social support, and parental skills and abilities may significantly reduce parental stress and alleviate burnout (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018). In the current study, we hypothesise that mothers of children W-SND will report higher perceived burden of treatment than mothers of children WO-SN.

Emotion Work as a Protective Factor

The theory of emotion management (Hochschild, 1979, 1983, 2012), suggests that human emotions are part of social construction and that society and culture dictate appropriate human feelings and establish standards of behavior. These "feeling rules" are forced on the individual by society, directly or implicitly. Through emotion work (EW), people manage and adapt their experienced emotions to the emotions that they perceive are expected from them in social circumstances, according to their specific context and situation. While EW refers to the private sphere, the term "emotional labor" relates to the process of managing feelings and expressions to fulfill the emotional requirements of a job (Grandey, 2000; Hochschild, 1983). In this study, we focus on mothers’ EW which has feminist origins and context (Hochschild, 1983, 2012). This is relevant to this study of mothers where more than half belong to a highly patriarchal society, which may impact on their perceived sense of their burden of care and consequently of burnout. Thus, EW involves attempts to suppress unwanted emotions while evoking desirable emotions that are suitable for social situations. This is usually carried out unconsciously but can become a conscious approach when individuals feel an emotional gap between their experienced emotions and those they perceive as expected emotions.

Deep EW and Surface EW

People perform deep EW by attempting to match their experienced emotions to the relevant social rules (as they perceive them), in order to create a real change in their feelings. Deep acting may include cognitive, physical, and expressive work, either separately or in combination. Research findings indicate that deep EW reduces fatigue and may improve work-life balance (Gabriel et al., 2020). It may enhance the sense of self accomplishment, which in turn reduces burnout (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Montgomery & Panagopolou, 2006). Deep EW is beneficial especially when tasks are perceived as challenging (Huang et al., 2015). In contrast, by surface acting or surface EW, people consciously act out the socially expected emotions rather than feel their authentic emotions (Hochschild, 1983). Over time, this suppression of authentic emotions deprives people of the possibility to correctly judge their condition. Consequently, individuals will function automatically and be emotionally detached from themselves and their actions. This can lead to self-frustration, decrease in self-esteem, and burnout (Hochschild, 2012). Therefore, deep EW may be an emotional resource that can potentially serve as a protective factor which may help parents to cope with PB. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that mothers of children W-SND will report higher use of deep EW as a coping resource than mothers of children WO-SN, indicating that deep EW is a protective resource for mothers of children W-SND. To date, most studies examining EW have been conducted among service providers and workers. They have shown a direct relationship between a person’s ability to perform deep EW and the degree of their burnout at work (Jeung et al., 2018). Studies have also found that deep EW helps reduce burnout resulting from the sense of a burden of care among formal caregivers. Conversely, failure of caregivers’ ability to manage their emotions creates a feeling of pressure and increases the burden of care (Kim & Kim, 2015). In the context of the present study, it can therefore be assumed that the sense of burden of care felt by mothers (as informal caregivers) may mediate the relationship between EW and the level of PB. Accordingly, we hypothesize that deep EW will help reduce the sense of the burden of care and reduce PB.

The Present Study

The study was conducted among mothers with and without children with SNs from two main Jewish religious sectors in Israel, the ultra-orthodox and the non-orthodox. The ultra-orthodox society in Israel composes about 12% of the population. It is considered to be a conservative religious Jewish community. The ultra-orthodox family has unique demographic characteristics, such as marriage at a young age, high fertility rates, and a clear hierarchal structure (men typically don’t work and are involved in religious studies, while women assist their husbands and are in charge of childcare, education and financial support for the family; Cahaner & Malach, 2019). Generally, ultra-orthodox parents are less likely to terminate pregnancies due to pre-natal screenings. This study focuses on the possible results of these decisions and how mothers in this community cope with a child with special needs. (To control the caregiving burden, we limited the number of children with special needs in the family to one SN child only). The ultra-orthodox community have an ambivalent approach towards special needs and disability in the family. Namely, they have a moral responsibility and grace towards individuals born with disabilities, but simultaneously have an attitude of rejection towards the "different" due to concern about injuring their social status in the community (Kandel, 2010). The aim of the current study was to examine the relationships between burden of treatment, emotions, EW and PB, among Israeli mothers of children with and without special needs in both ultra-orthodox and non-orthodox families. The following hypotheses were examined:

-

1.

PB will be found higher among mothers of children W-SND as compared to mothers of children WO-SN.

-

2.

Burden of Treatment and child dependence will be found higher among mothers of children W-SND as compared to mothers of children WO-SN.

-

3.

Deep emotion work will be found higher among mothers of children W-SND as compared to mothers of children WO-SN.

-

4.

Among all mothers, a positive correlation will be found between burden of treatment and PB.

-

5.

Among mothers of children W-SND, a positive correlation will be found between Deep Emotion Work and burden of treatment.

-

6.

Among mothers of children W-SND, a positive correlation will be found between Deep Emotion Work and PB.

Methods

Participants

The sample included 98 mothers: 46.94% have children W-SND with disabilities treated in two child development centers and 53.06% have children without special needs (WO-SN) treated in two mother–child health centers in Israel. About 54.00% of the mothers of children WO-SN and about 52.00% of the mothers of children W-SND are ultra-orthodox (the rest are non-orthodox, including religious, traditional or secular). Through a non-probability convenience sampling procedure, mothers who expressed consent to participate in the study were included.

Design

A quantitative descriptive, cross-sectional pilot study utilizing a self-report validated questionnaire.

Instruments

The Parental Burnout Assessment

PB was measured using the PBA (Parental Burnout Assessment; Roskam et al., 2018) which includes 23 items (Cronbach alpha = 0.96, in the current study = 0.95). The questionnaire was translated from English-to-Hebrew using the translation – back-translation procedure), changing "parents" to "mothers". It includes four PB dimensions (“reliabilities” according to Roskam et al., 2018): Physical and emotional exhaustion in the parental role, Cronbach alpha = 0.98, nine items; Emotional distancing from the child, Cronbach alpha = 0.95, three items; Saturation from the parental-role, Cronbach alpha = 0.94, five items; and Contrast with previous parental-self, Cronbach alpha = 0.96, six items. Mothers were asked to indicate how often they felt each emotion on a scale ranging from 1 = “not at all” to 7 = “every day”. The mean PB and mean of each dimension ranged between 1 and 7. Additionally, the risk levels were calculated according to the suggestion of Roskam et al. (2018) regarding the conceptualization and measurement of PB, as follows: the sum of the responses (range 23–161 [23*1 – 23*7]) to all the items was categorized into a five-rank scale of risk of PB:

0 = “no PB” (< 35), 1 = “low risk” (36–53), 2 = “medium risk” (54–70), 3 = “high risk” (71–88), and 4 = “has PB” (89 +).

Caregiver’s Burden of Treatment

The caregiver’s burden of treatment questionnaire (Bedard et al., 2001; Zarit et al., 1980), Cronbach alpha = 0.83 (Bachner & Ayalon, 2010) and found to be reliable (Cronbach alpha = 0.88; Fine, 2018). It includes 12 items ranked from 1 = “never” to 7 = “daily”. The final score is the sum of the responses which ranges between 12 and 84. A high score indicates a high level of burden of treatment. In the current study, the reliability Cronbach alpha was 0.86.

Emotions and Emotion Work Questionnaires

The first two parts of this questionnaire are based on Hochschild’s (1979) theory of emotion management and are designed to examine whether and to what extent mothers perform EW while caring for their child.

In order to establish content validity, a focus group of ten mothers of children W-SNDs was interviewed by the researcher in a 2-h session at a child development center. The participants of the focus group were requested to express their emotions regarding childcare so we could establish that they were emotions most relevant to the topic of the current study, based on Watson et al. (PANAS scale, 1988).

Following the focus group, ten general emotions were expressed by the mothers: six negative emotions (distress, frustration, sadness, anxiety, anger, mercy) and four positive emotions (pride, gratefulness, happiness, hope).

EW was examined by assessing the emotions the mother experiences while taking care of her child, her perceptions of the society’s expectations of her emotions, and the gap between them. Additionally, the mothers’ deep EW was examined. The mothers were requested to rank each emotion on a scale ranging from 1 = “do not feel it at all” to 5 = “feel it very much”. Two scores were calculated (experienced and expected emotions) as the sum of the six positive emotions and of the inversion of the four negative emotions. The range of scores was between 10 and 50.

The third part of the questionnaire examines EW. The questionnaire includes 13 statements based on Furman et al.’s (2021) questionnaire and adapted by the researchers for mothers (the use and necessary changes were approved by the authors of the questionnaire). The mothers were requested to rank their agreement with the statements regarding deep EW on a scale ranging from 1 = “do not agree at all” to 5 = “agree very much”. The mean of the statements ranges between 1 to 5 and a high score indicates deep EW. According to Furman et al. (2021), the reliability of the questionnaire is high (Cronbach alpha = 0.93) and also in the current study (Cronbach alpha = 0.86).

Background Characteristics

The background characteristics data included religious definition (ultra-orthodox, non-orthodox), education, country of birth, marital status, age, number of work hours a week, the number of children, whether they receive child-caring paid help, whether they receive child-caring help from family members and husband, and finally, the child’s schooling framework. The mothers were also asked two additional questions:

Caregiver’s perceived level of child’s disability or difficulty/challenge in raising their child

Mothers of children W-SND were asked to define their perception of the severity of their child’s daily functional disability on a five-rank scale (1 = “very mild”, 5 = “very severe”). At the same time, mothers of children WO-SN were asked whether they found that raising them is challenging or difficult (0 = “no” / 1 = “yes”). In order to compare the perceived severity of the disability of children W-SND to the challenge/difficulty in raising children WO-SN, the values severe / very severe were recoded to 1, and the rest (very mild / mild / moderate) were recoded to 0.

Self-utilization of Health Services by the Caregiving Parent

The mothers were asked if they have a chronic illness, what was their health condition in the last month, and if they needed medical treatment services to cope as mothers. Additionally, they were asked three questions to assess the frequency of their use of health services due to medical problems arising from their need to cope as mothers. The assessment used an index constructed by Reijneveld and Stronks (2001), which estimates the number of times in the last two weeks a mother has visited (physically or online) a family doctor, a specialist, a nurse, a paramedical, or a mental health therapist.

Data Analyses

The data were processed using SPSS for Windows version 27. As part of this pilot study, the reliability of the questionnaires among the study samples was examined. Descriptive statistics included frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations. The inference statistics included a comparison between mothers of children W-SND and WO-SN, using χ2 tests and independent samples t-tests. The significance of the differences in the correlations between the groups was examined using Steiger’s Z (Weiss, 2011).

Procedure

The questionnaires were distributed by nurses and secretaries working in two mother–child health centers and two child development centers to mothers of children WO-SN and W-SND, in anonymous sealed envelopes for three months (May through July, 2020). The nurses received guidance from the researchers regarding the aims of the study and knew how to answer the respondents’ questions. Mothers who agreed to participate in the study received a brief oral and written explanation about the aim of the study and were promised anonymity. One-hundred and ten questionnaires were distributed, and 98 mothers completed the questionnaires (an 89% response-rate).

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Helsinki committee of "Meuhedet Health Services Clinics" (approval number 02290120) and by the ethics committee of Tel-Aviv University (approval number 0001222–2). According to the Helsinki committee approval, informed consent was accepted by the mothers’ agreement to complete the questionnaire.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

The research sample included 98 mothers, 52 (53.06%) to children WO-SN and 46 (46.94%) to children W-SND with one or more disabilities: autistic-spectrum disorders (50.00%), physical disability (30.43%), cognitive developmental disabilities (28.26%), visual impairment (6.52%), hearing impairment (4.35%), mental disabilities (2.17%). As shown in Table 1, all mothers were Jewish of whom 53.06% were ultra-orthodox. Most were born in Israel (86.73%) and all except two were married. Mothers of children W-SND were significantly older than mothers of children WO-SN (40.30 ± 6.48 versus 33.77 ± 5.76 years, respectively; t(96) = 5.29, p ≤ 0.000). The mothers worked 28.06 ± 8.97 h a week.

Most mothers did not have a chronic illness. However, there was a 2.5 times higher proportion of mothers of children WO-SN reporting very good health (53.85%) compared to those of children W-SND (21.74%); χ2 = 12.46, p = 0.002. Thirty-eight percent of mothers of children W-SND reported that they needed medical treatment due to the health consequences of caring for their child. This was 2.5 times higher than for mothers of children WO-SN (15.69%); χ2 = 6.49, p = 0.011. Moreover, mothers of children W-SND reported more harm to their health due to caring for their child than mothers of children WO-SN (2.91 ± 1.94 versus 1.71 ± 1.29; t (76) = 3.56, p ≤ 0.001. Moreover, 36.93% of mothers of children W-SND reported that they had at least once in the last two weeks consulted a healthcare provider as a result of their maternal responsibilities; a significantly higher rate compared to mothers of children WO-SN (17.31%); χ2 = 4.87, p = 0.039. The distribution of additional characteristics of the mothers and their families are provided in Table 1.

Comparisons between Mothers of Children W-SND and Mothers of Children WO-SN

Parental Burnout

Table 2 shows that on average, mothers of children W-SND expressed a moderate PB)2.29 ± 1.02), but this was significantly higher compared to mothers of children WO-SN (1.41 ± 0.50); t = 5.51, p ≤ 0.001. Multiple analysis of variance of the four PB dimensions indicated a significant difference in their distributions between mothers of children W-SND and WO-SN (F(4,93) = 9.25). However, although the differences in PB dimensions are significantly different between groups, the largest difference in PB was found in the dimension of physical and emotional exhaustion in the parental role (F(1,96) = 31.24, contrast estimate = -1.30). Yet, a similar tendency was found in the other three burnout dimensions (emotional distancing from the child, saturation from the parental role, and contrast with previous parental-self). A significant association was found between having children W-SND or WO-SN and the risk of PB (χ2 = 37.60, p ≤ 0.000). These finding confirm hypothesis 1.

Burden of Treatment and the Severity Level of the Child’s Disability / Difficulty in Raising the Child

Table 3 shows that mothers of children W-SND reported a significantly higher burden of treatment than mothers of children WO-SN (35.17 ± 13.02 versus 30.02 ± 10.91; t = 2.13, p = 0.036). Mothers of children W-SND also reported a moderate level (3.72 ± 1.20) of the child’s dependence on them while mothers of children WO-SN reported a significantly higher level of independence (4.20 ± 0.89);

t = 2.24, p = 0.028. About 30% of all mothers reported a high level of difficulty in raising the child, due to the SN child’s severity of disability or the general challenges in raising a child WO-SN. These finding confirm hypothesis 2.

Emotions and Emotion Work

Mothers of children W-SND reported experiencing most often (i.e. with a score of 4 or higher on a 1–5 scale) while caring for their children two emotions: hope (4.39 ± 0.86) and joy (4.04 ± 0.94). While the mothers of children WO-SN most often experienced while caring for their children four emotions: joy (4.87 ± 0.40), hope (4.62 ± 0.66), gratefulness (4.58 ± 0.82) and pride (4.48 ± 0.94). The emotion most often perceived as expected among mothers of children W-SND was hope (4.15 ± 0.97) while among mothers of children WO-SN four emotions were most often perceived as expected: joy (4.77 ± 0.58), gratefulness (4.75 ± 0.44), pride (4.58 ± 0.82) and hope (4.54 ± 0.75). The mean deep EW among mothers of children W-SND was moderate (2.99 ± 0.74) and significantly higher than that of mothers of children WO-SN (2.44 ± 0.81); t = 3.53 p ≤ 0.001. Namely, mothers of children W-SND reported deeper EW than mothers of children WO-SN (Table 3). This finding confirms hypothesis 3.

Correlations

The Correlation between Burden of Treatment and PB

Mothers who perceived a high burden of treatment reported a higher PB. Among all the mothers, a positive, relatively high and significant correlation was found between the burden of treatment and PB (ρ = 0.62, p ≤ 0.001). The highest correlations were found in the sense of contrast with previous parental-self dimension (ρ = 0.64, p ≤ 0.000) and the dimension of physical and emotional exhaustion in the parental-role (ρ = 0.59, p ≤ 0.000). Similarly, positive, moderate, and significant correlations were found between the saturation from the parental-role (ρ = 0.44, p ≤ 0.000) and the emotional distancing from the child dimensions (ρ = 0.39, p ≤ 0.000). Systematically, the correlations were stronger among mothers of children W-SND compared to mothers of children WO-SN in the overall PB and the four dimensions of the PBA.

Among mothers of children W-SND in the dimension of the saturation of the parental-role, the correlation with the burden of treatment was positive, moderate and significant (ρ = 0.56, p ≤ 0.001), while among mothers of children WO-SN, the correlation was relatively low (ρ = 0.29, p = 0.037). In accordance with these findings, in both groups, a positive, high and significant correlation was found between the burden of treatment and the level of PB (ρ = 0.67, p ≤ 0.001). Additionally, a positive, moderate correlation was found between the perceived severity level of the child’s disability and the burden of treatment (ρ = 0.51, p ≤ 0.001, N = 46). According to these findings, hypothesis 4 is confirmed.

The Correlation between Deep Emotion Work and Burden of Treatment

According to hypothesis 5, among mothers of children W-SND, the burden of treatment was positively correlated with deep EW (ρ = 0.46, p ≤ 0.001). In contrast, this correlation was not found among mothers of children WO-SN. Additionally, in both groups, the less the mothers perceive their burden of treatment, the more positive are the emotions they experience while caring for their children; mothers of children W-SND: ρ = -0.61, p ≤ 0.001 and mothers WO-SN: ρ = -0.41, p = 0.002. Non-significant correlations were found between the burden of treatment and the perceived emotions the mothers think are expected of them by society.

The Correlation between EW and PB

According to hypothesis 6, the correlation between deep EW of mothers of children W-SND and their level of PB was positive, moderate and significant (ρ = 0.35, p = 0.018). In contrast, among mothers of children WO-SN this correlation was positive, low and not significant (ρ = 0.18, p = 0.202). It was also found that in both groups, the more positive the emotions experienced by the mothers when caring for their child, the lower their level of PB (ρ = -0.62, p ≤ 0.001).

A significant difference was found between the correlations of mothers with/without SN in the emotional distancing from the child dimension of the PBA (Steiger’s Z = 2.64, p = 0.01). Namely, among mothers of children W-SND the correlation between their experienced emotions and the emotional distancing dimension was negative, high and significant (ρ = -0.60, p ≤ 0.000), whereas among mothers of children WO-SN the correlation was negative, low and insignificant. Accordingly, the more mothers experienced negative emotions while child-caring, the higher their sense of emotional distancing from their child.

The relationship between the perceived expected emotions and the level of PB among all mothers was negative, moderate and significant (ρ = -0.41, p ≤ 0.001) overall and in each of the four PBA dimensions. The correlation between the perceived expected emotions and the feeling of saturation from the parental-role dimension was also found to be negative, moderate and significant among mothers of children WO-SN (ρ = -0.31, p < 0.05). Namely, the more positive they perceived the emotions expected of them by society, the lower they reported saturation from the parental-role. In contrast, among mothers of children W-SND this correlation was negative, very low and not significant.

Discussion

Mothers of children W-SND with disabilities reported a significantly higher PB and burden of treatment. They experienced most often the emotions of hope and joy while caring for their children but perceived as expected only one emotion, hope. In contrast, mothers of children WO-SN reported a significantly lower PB and burden of treatment. They experienced most often the emotions of joy, hope, gratefulness and pride while caring for their children and perceived as expected the same four emotions. Thus, the gap between experienced and expected emotions is larger among mothers of children W-SND, which consequently results in them performing deeper EW.

A possible explanation of the relatively high PB of mothers of children W-SND is the actual difficulty they experience in raising, caring for and providing a therapeutic response to their child’s prolonged health needs. This difficulty causes them a sense of caregiver-burden (Bedard et al., 2001; Gérain & Zech, 2018), and a need to deal with emotional, social, mental and economic stress over-time. These parents often tend to neglect their personal, physical and emotional needs; one of the main reasons for them experiencing more symptoms of physical and emotional exhaustion resulting from their role as parents (Gérain & Zech, 2018; Vinayak & Dhanoa, 2017). Hence, the parental need to consistently provide prolonged care for their child leads to high PB (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018). PB has both physical and emotional symptoms, such as high levels of anxiety, fear, insomnia, anger, guilt, grief and depression which necessitate recourse to health services for appropriate medical care (Adriaenssens et al., 2015; Bedard et al., 2001). This study also found that the reported health status of these mothers is worse than that of mothers of children WO-SN. Similar to the findings of the present study, evidence has been found that mental distress, as a manifestation of ongoing life stress and the constant struggle with problems related to managing child-care, may lead to a depletion of emotional and physical resources and increased maternal use of health services (Benyamini et al., 2008). Additionally, higher levels of stress, negative emotions, and physical symptoms have been observed among parents of adolescent children with disabilities (Seltzer et al., 2009), and their cortisol level (as a measure of stress) was significantly higher than that of parents of children without disabilities (Bedard et al., 2001).

In Israel and worldwide, raising children is a challenge for parents, especially if their child has a disability that requires unique parental care and coping (Khan & Alam, 2016). The comparison between the level of difficulty or challenge of mothers in raising children in the current study, revealed that about one-third of them reported high levels of difficulties/challenges in raising their child. However, surprisingly, mothers of children W-SND reported less dependence of the child on them, compared to mothers of children WO-SN. Possibly, families with a child W-SND are socially recognized as needing help and support and therefore a routine develops in which the child receives external assistance and is not dependent on the mother and their family exclusively. It is important to note that in Israel, the state provides extensive social support and services to families with children with special needs and disabilities. These include a monthly allowance, subsidized medical and therapeutic treatments, a teaching-assistant in kindergartens and schools etc. Additionally, it is common in Israel that close and extended family assists in childcare responsibilities (Feldman, 2009; Rubin et al., 2017). Indeed, children with severe disabilities, compared to milder ones, require parents to be primarily responsible for complex intensive care, but social recognition leads to society providing assistance that facilitates parents and reduces child dependence on them as the exclusive caregiver (Gardiner & Iarocci, 2012). In most cases, families with children WO-SN that have one or more challenging children that are relatively highly dependent on their parents, do not usually receive formal assistance from society.

Raising and caring for children with the many struggles involved, is accompanied by a complex emotional experience. In addition to positive emotions (such as joy and pride), parents sometimes experience negative emotions (such as anger and sadness) (Nelson et al., 2013). In the present study, we found that while caring for their child, mothers of children W-SND reported experiencing most often two emotions: hope and joy, but they estimate that society expects them to feel mostly hope (in comparison to the other emotions). In contrast, mothers of children WO-SN report experiencing most often while caring for their child four emotions: joy, hope, gratefulness and pride, which are all perceived as expected emotions by society. The findings show that mothers of children W-SND do not report experiencing emotions of gratefulness and pride nor perceive them as expected by society; these two emotions were found to be only experienced and perceived as expected by mothers of children WO-SN. It is possible that experiencing gratitude and pride while caring for a child can compensate or even reward mothers of children W-SND for their ongoing efforts, thus alleviating their sense of difficulty in raising their child. We suggest that further investigation is warranted to examine other factors and causes as to why mothers of children W-SND do not experience these positive emotions.

This study found that in general for mothers, the more the emotions they experienced and were expected to experience were positive, the lower their level of PB. A variety of factors may explain this relationship. A previous study found that five parental personality traits are associated with high PB: a high level of neuroticism, a low-level of conscientiousness, a low-level of agreeableness, a low-level of openness, and a high level of extraversion)Le Vigouroux et al., 2017). The researchers explained that parents with these characteristics tend to develop PB syndrome due to their tendency to be emotional distant from their children and their inability to experience positive emotions while caring for them. These factors might create difficulties in identifying and meeting their children’s needs and in providing them with a structured and coherent environment.

The relationship between the experienced emotions was found mainly with the emotional distancing index of the PBA and only among mothers of children W-SND. This finding is consistent with the theoretical framework proposed by Mikolajczak and Roskam (2018), according to which parents with high PB feel emotionally drained as they think about their parental role, even describing it as reaching the limits of their capability. Thus, they become emotionally distant from their children and gradually become less and less emotionally involved in the relationship with their child. Moreover, their functioning skills become mechanical, and they tend to limit their interaction with their child to only practical aspects. However, this explanation is true for all parents and not necessarily for only parents of children W-SND. Therefore, we propose to further examine this relationship among parents of children with developmental health characteristics and different needs. Furthermore, parents’ continuous adherence to the rules of emotions that society dictates may over time lead to the suppression of their authentic emotions and the inability to properly judge their condition. This, in turn, can lead to automatic functioning which is characterized by an emotional detachment from the actions they perform. This emotional detachment comes at a personal cost that includes a sense of frustration, self-hatred and decreased self-esteem, and can lead to PB (Hochschild, 1979, 2012).

This study’s findings provide another perspective on the relationship between the mothers’ emotions and PB. Namely, the more positive the mothers of children WO-SN perceive the emotions expected of them by society, the lower their level of burnout and saturation from their parental-role (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018). Mothers of children WO-SN may be more emotionally available to absorb and relate to society’s expectations of their parental-role so that they are able to perceive their emotions as positive and desirable when caring for their child. As a result, their level of burnout may be lower and their sense of enjoyment of parenthood higher. The absence of a similar correlation among mothers of children W-SND can be explained by the possibility that a variety of other factors influence their PB, and society’s expectations of their emotions have a relatively low impact on this relationship. Another finding was that the lower their sense of burden of caring for the child, the more positive the emotions the mothers in both groups experience when caring for their child and vice versa. According to the literature, the ability of primary caregivers to experience and manage emotions is related to the sense of stress they experience and their perception of the burden of care (Kim & Kim, 2015). Thus, we suggest examining the possible mitigating contribution of positive emotions in general, and deep EW in particular, to feeling the burden of child-caring and parental burnout.

Mothers of children W-SND reported significantly deeper EW (albeit at a moderate level) than mothers of children WO-SN (low-medium level). It was also found that among mothers of children W-SND, deep EW was associated with a high level of burnout, while among mothers of children WO-SN, no similar association was found. It is possible that deep EW is carried out mainly by mothers (especially children W-SND) whose level of burnout is relatively high. It is also possible that for mothers of children W-SND, this effort, which involves managing their emotions in addition to the other stresses in their lives, leads to a higher sense of the burden of caring for their child and high PB.

Study Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, it is a pilot study consisting of a relatively small sample that was recruited by convenience sampling, which might not represent the population well enough. Thus, further research should be conducted among larger samples and additional cultural societies. Furthermore, mothers were chosen to be the subject of this research because they are still considered to be the primary caregiver (especially in the ultra-orthodox society, Kandel, 2010). However, due to the growing involvement of fathers in childcare (in certain classes and sectors in the Israeli society; Cahaner & Malach, 2019), further research should also include fathers. Second, the sample of this pilot study is too small to run a SEM analysis (there are less than the required sample 10–20 participants per variable, see Wolf et al., 2013) – that provides a more integrative perspective on the multiple relationships between the independent variables related to PB and control variables.

Future research therefore should, as mentioned above, include a larger sample; this will allow hypotheses to be tested using SEM path analyses (direct and indirect effects, mediation and moderation). Third, the context of healthcare interactions might introduce bias to the composition of the sample. We did ensure that the staff received explanations and directions in order to ensure minimal bias. Nevertheless, there were possible confounders found that may introduce bias. For example, it was found that mothers to children W-SND were significantly older than mothers to children WO-SN. Therefore, mothers’ ages and the length of time parenting should be considered in future research as an additional predictor, mediator or moderator of PB. Finally, this pilot study focused on comparing mothers with and without children with special needs. The sample consisted of two main religious sectors in Israel, the ultra-orthodox and the non-orthodox (mostly secular or traditional). Future research with a larger sample can make comparisons within each sample (W-SND / WO-SN) of these two religious sectors (ultra-orthodox / non-orthodox), including the possible differences in social perceptions and behaviors among these societies. Furthermore, Direct information regarding severity levels and types of disorders was not collected (it was not approved by the child development centers and the mother–child health centers). Therefore, it is recommended collecting this information in future studies.

Implications for Practice

The findings of the study give an understanding of some of the factors related to PB with suggestions on ways to reduce PB. For instance, effective coping resources, such as deep EW, may contribute to creating empirically based professional guidance recommendations for policy makers and treatment teams. In addition, the study’s findings about mothers W-SND’s use of health services due to the impact that their burden of child-caring has on their health may help health services plan and develop ways to deal with these pressures and difficulties. In this way, there is opportunity to reduce the potential health consequences for mothers and in turn, their dependence on health services.

Conclusions

Mothers of children W-SND experience PB and have a higher burden of child-caring than mothers of children WO-SN. However, mothers of children WO-SN report more child dependence on them than mothers of children W-SND. There is a similar rate of mothers of children with and without SN who have a high level of difficulties and challenges in raising their children. Mothers of children W-SND perform deeper EW and experience most frequently the emotions of joy and hope when caring for their child. Whereas mothers of children WO-SN feel gratefulness and pride in addition to joy and hope when child-caring. So far, most studies have examined the negative implications of EW while the current research studies possible positive aspects of adapting emotions to social expectations, which may lead to a lower perceived burden of treatment and thus, lower PB. However, further research should examine which additional factors may be related to PB and to the development of coping mechanisms for mothers of children W-SND.

References

Adriaenssens, J., De Gucht, V., & Maes, S. (2015). Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: A systematic review of 25 years of research. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(2), 649–661.

Alfasi Henley, M. (2016). Difficulties in everyday life among the parents of children with disability. http://www.economy.gov.il/Research/Documents/X13231.pdf. Accessed 29 March 2022

Bachner, Y. G., & Ayalon, L. (2010). Initial examination of the psychometric properties of the short Hebrew version of the Zarit Burden Interview. Aging & Mental Health, 14(6), 725–730.

Bedard, M., Molloy, W., Squire, L., Dubois, S., Lever, J., & O’Donnell, M. (2001). The Zarit Burden Interview: A new short version and screening version. The Gerontological Society of America, 41, 652–657.

Benyamini, Y., Blumstein, T., Boyko, V., & Lerner-Geva, L. (2008). Cultural and educational disparities in the use of primary and preventive health care services among midlife women in Israel. Women Health Issues, 18, 257–266.

Bezliudnyi, O., Kravchenko, O., Maksymchuk, B., Mishchenko, M., & Maksymchuk, I. (2019). Psycho-correction of burnout syndrome in sports educators. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 19(3), 1585–1590.

Bianchi, R., Schonfeld, I. S., & Laurent, E. (2015). Burnout-depression overlap: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 36, 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.004

Brotheridge, C., & Grandey, A. (2002). Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of “People Work.” Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60, 17–39.

Cahaner, L., & Malach, G. (2019). Shnaton hahevra haharedit be’Israel 2019 [The statistical report on ultra-orthodox (Haredi) society in Israel]. The Israeli institute of Democracy.

Carroll, D. W. (2013). Families of children with developmental disabilities: Understanding stress and opportunities for growth. American Psychology Association.

Feldman, D. (2009). Human rights of children with disabilities in Israel: The vision and the reality. Disability Studies Quarterly, 29(1), 44–68.

Fine, M., (2018). The Relationship between stress, burden and ambivalence. Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev.

Furman, G., Bluvstein, I., & Itzhaki, M. (2021). Emotion work and resilience of nurses and physicians towards Palestinian Authority patients. International Nursing Review, 68(4), 493–503.

Gabriel, A. S., Koopman, J., Rosen, C. C., Arnold, J. D., & Hochwarter, W. A. (2020). Are coworkers getting into the act? An examination of emotion regulation in coworker exchanges. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(8), 907–929. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2019-71495-001. Accessed 29 March 2022

Gardiner, E., & Iarocci, G. (2012). Unhappy (and happy) in their own way: A developmental psychopathology perspective on quality of life for families living with developmental disability with or without autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33, 2177–2192.

Gérain, P., & Zech, E. (2018). Does informal caregiving lead to PB? Comparing parents having (or not) children with mental and physical issues. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 884.

Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotion regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 59–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95.PMID10658889.S2CID18404826

Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion Work feeling rules and social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85, 551–575.

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. University of California.

Hochschild, A. R. (2012). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. In (author, Ed.), The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. University of California.

Huang, J. L., Chiaburu, D. S., Zhang, X. A., Li, N., & Grandey, A. A. (2015). Rising to the challenge: Deep acting is more beneficial when tasks are appraised as challenging. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(5), 1398. https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2015-09762-001. Accessed 29 March 2022

Jeung, D. Y., Kim, C., & Chang, S. J. (2018). Emotional labor and burnout. Yonsei Med Journal, 59, 187–193. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2018.59.2.187

Kandel, I. (2010). Yachasa ve’emdote’ha shel ha'hevra ha'haredit bemedinat Israel klapey ha'yeled ha'harig [The attitudes of the ultra-orthodox society towards different children]. Orot Israel College.

Khan, M. F., & Alam, M. A. (2016). Coping trends of parents having children with developmental disabilities: A literature review. European Journal of Special Education Research, 1(3), 39–49.

Kim, C. S., & Kim, J. (2015). The Impact of emotional labor on burnout for caregivers of stroke patients Korean. Journal of Occupational Health Nursing, 24(1), 31–38.

Lastovkova, A., Carder, M., Rasmussen, H. M., Sjobergg, L., de Groene, G. J., Sauni, R…., et al. (2018). Burnout Syndrome as an occupational disease in the European Union: An Exploratory Study. Industrial Health, 56, 160–165.

Le Vigouroux, S., Scola, C., Raes, M. E., Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2017). The big five personality traits and parental burnout: Protective and risk factors. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 216–219.

Lindström, C., Åman, J., & Lindahl Norberg, A. (2010). Increased prevalence of burnout symptoms in parents of chronically ill children. Acta Paediatrica, 99, 427–432.

Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2018). A theoretical and clinical framework for parental burnout: The balance between risks and resources. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 886.

Mikolajczak, M., Brianda, M. E., Avalosse, H., & Roskam, I. (2018). Consequences of parental burnout: Its specific effect on child neglect and violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 134–145.

Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., Stinglhamber, F., Lindahl Norberg, A., & Roskam, I. (2020). Is parental burnout distinct from job burnout and depressive symptoms? Clinical Psychological Science, 8(4), 673–689.

Montgomery, A. J., & Panagopolou, E. (2006). Work-family interference, emotional labor and burnout. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(1), 36–51.

Nelson, S. K., Kushlev, K., English, T., Dunn, E. W., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2013). In defense of parenthood: Children are associated with more joy than misery. Psychological Science, 24, 3–10.

Reijneveld, S. A., & Stronks, K. (2001). The validity of self-reported use of health care across socioeconomic strata: A comparison of survey and registration data. International Journal of Epidemiology, 30, 1407–1414.

Roskam, I., Brianda, M. E., & Mikolajczak, M. (2018). A step forward in the conceptualization and measurement of Parental Burnout: The Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 758. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00758

Rubin, L., Belmaker, I., Somekh, E., Urkin, J., Rudolf, M., Honovich, M., ..., & Grossman, Z. (2017). Maternal and child health in Israel: building lives. The Lancet, 389(10088), 2514-2530.

Schonfeld, I. S., & Bianchi, R. (2016). Burnout and depression: Two entities or one? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(1), 22–37.

Seltzer, M. M., Almeida, D. M., Greenberg, J. S., Savla, J., Stawski, R. S., Hong, J., & Taylor, J. L. (2009). Psychosocial and biological markers of daily lives of midlife parents of children with disabilities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(1), 1–15.

Van Bakel, H. J., Van Engen, M. L., & Peters, P. (2018). Validity of the PB Inventory among Dutch employees. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 697.

Vinayak, S., & Dhanoa, S. (2017). Relationship of PB with parental stress and personality among parents of neonates with hyperbilirubinemia. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 4, 102–111.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070.

Weiss, B. A. (2011). Hotelling's t Test and Steiger's Z test calculator [Computer software]. Available from https://blogs.gwu.edu/weissba/teaching/calculators/hotellings-t-and-steigers-z-tests/. Accessed 29 March 2022

Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., & Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample Size Requirements for Structural Equation Models: An Evaluation of Power, Bias, and Solution Propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(6), 913–934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164413495237

Zarit, S. H., Reever, K. E., & Bach-Peterson, J. (1980). Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist, 20, 649–655.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Declarations of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Findling, Y., Barnoy, S. & Itzhaki, M. Burden of treatment, emotion work and parental burnout of mothers to children with or without special needs: A pilot study. Curr Psychol 42, 19273–19285 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03074-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03074-2