Abstract

The objectives of the present study were, first, to analyze the impact of direct and relational bullying on emotional well-being, and second to study if self-compassion could foster emotional well-being among those who suffer bullying. A sample composed of 433 adolescents (Mage = 13.28; SD = .72) answered two measures of direct and relational bullying based on the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire, the Self-Compassion Scale, and the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). The results showed that being a victim of either relational or direct bullying was associated with lower scores in positive affect and negative affect, while direct bullying was only associated with negative affect. Self-compassion was a strong predictor of emotional well-being, and self-compassion was a partial mediator between being a victim of bullying (either relational or direct) and negative affect. This research adds evidence that self-compassion may be an important component in prevention and intervention programs with victims of bullying.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescence is a phase of deep hormonal, cognitive and moral changes, as well as of identity development. It is a stage characterized by great neural plasticity, in which desirable or harmful experiences have a determining impact on brain circuitry, affecting well-being and psychopathology both during adolescence and adulthood (Susman & Dorn, 2009). During this stage, relationships with others gain great importance as they become references and influence self-view. Positive relationships foster personal well-being, while harmful relationships can impair healthy development and have serious consequences on present and future mental health (Hayden & Mash, 2014; Patton et al., 2018). An extreme yet common case of a harmful relationship is bullying.

Bullying has been defined as a type of violent behavior in which a peer or a group of peers intentionally harasses, humiliates and/or intentionally excludes another peer who is in a situation of power imbalance (Olweus, 1993). In order for this type of peer violence to be considered bullying, it must occur frequently and over a period of time (Salmivalli, 2010). The negative actions exercised over victims can be categorized into two groups: direct or indirect. Direct bullying refers to violence targeted against the victim and tends to include physical (e.g., hitting, pushing, tripping) and verbal aggressions (e.g., name calling, insulting) (Björkqvist, 1994). Relational bullying (e.g., gossiping, rumor spreading, social exclusion) intends to damage the victim’s social status and eventually isolate them from their peers (Archer & Coyne, 2005).

Bullying is global health issue due to its prevalence and to the negative consequences for the victims. A study with a sample of 317,869 adolescents from more 80 countries established a prevalence rate for victims from 8% in European zone and to 45.1% in Eastern Mediterranean countries, which means that millions of adolescents worldwide are suffering from this form of violence (Biswas et al., 2020). Bullying appears to be particularly problematic in early adolescence as it generally decreases with age (Moon et al., 2015).

Suffering from bullying has been systematically associated with several psychopathological symptoms and indicators of distress. Victims are likely to report higher levels of depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms in comparison to non-victimized students (Idsoe et al., 2021; Moore et al., 2017). Meanwhile, longitudinal studies have proved that these problems might extend into adulthood (Lereya et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2017). Additionally, suffering from bullying is not only associated with psychopathological symptoms but also hinders the capacity of victims to experience well-being. A study with more than 47,029 children and adolescents from 15 countries found a moderate negative association between victimization and subjective well-being (Savahl et al., 2019).

Emotional well-being together with life satisfaction are the two components of subjective well-being, the latter being a cognitive overall evaluation of one’s own life, and the former the affective component of well-being, which has to do with having a high frequency of positive affect and a low frequency of negative affect (Diener et al., 2009). The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule has been frequently used in the literature to assess Emotional well-being (i.e. Bluth & Blanton, 2015; Lennarz et al., 2018). Positive affect refers to the extent to which a person experiences pleasant feelings such as vitality, energy, curiosity or enthusiasm. Negative affect reflects a general dimension of subjective distress that includes unpleasant feelings such as guilt, anger, fear or nervousness (Watson et al., 1988).

One promising factor that may help victims to cope with bullying and its negative consequences and foster emotional well-being is self-compassion, understood as the ability to hold one’s feelings of suffering with a sense of warmth, connection and concern (Neff, 2003). Self-compassion entails six components, three of them understood as compassionate attitude towards oneself (self-kindness, common humanity and mindfulness) and three that represent an uncompassionate attitude towards oneself (self-judgement, isolation and overidentification). Self-kindness refers to having a kind and healthy attitude instead of being harsh towards oneself (self-judgement). Common humanity refers to accept imperfection and failures as part of human experience rather than experiencing feelings of isolation when failure and letdowns occur. Mindfulness is defined in this context as holding a balanced perspective of one’s experience instead of being carried away by one’s owns emotions. Simply put, self-compassion is treating yourself as you would treat a good friend in a moment of suffering, with sympathy, concern and a profound desire for that person to improve their situation. Although these six components are separable in different scales and can be studied independently, self-compassion is understood as a system, due to the fact that changes tend to occur simultaneously within a person; they tend to foment one another, and they are balanced within individuals (Dreisoerner, et al., 2020; Ferrari et al., 2019; Phillips, 2019). The validity of using the score of one global factor has been previously proved (García-Campayo et al., 2014; Játiva & Cerezo, 2014; Neff et al., 2019).

Previous research has found a positive association between self-compassion and a number of positive outcomes and a negative association with several psychopathological symptoms. Self-compassion has been associated positively with variables such as life satisfaction, happiness, optimism, emotional well-being and emotional intelligence in adults (Baer et al., 2012; Y. Chen et al., 2016; Neff et al., 2007). Similar results have been found with samples of adolescents, although literature in this field is scarce and further research with more diverse samples is needed (Bluth et al., 2017). On the other hand, several studies stated a large effect size showing a negative association between self-compassion and anxiety, stress and depression symptomatology in adults (Denckla et al., 2017; MacBeth & Gumley, 2012) and in adolescents (Bluth & Blanton, 2015; Edwards et al., 2014; Marsh et al., 2018).

Furthermore, self-compassion can be a protective factor against the development of pathologies in particularly stressful or taxing situations. For example, self-compassion appears to protect against the development of panic, depressive and suicidal ideation symptomatology following traumatic events in adolescents (Zeller et al., 2015), and can be used to predict mental health in low self-esteem adolescents (Marshall et al., 2015). Evidence also shows that adolescents with higher levels of self-compassion show fewer depressive symptoms when facing academic difficulties (Lahtinem et al., 2020) or potentially traumatic events (Zeller et al., 2015).

Based on the literature mentioned above, it is reasonable to believe that direct and relational bullying may affect emotional well-being, and that self-compassion could be a powerful psychological tool to buffer the negative consequences of bullying among victims. However, the link between bullying and self-compassion has only recently begun to be researched, mostly in two lines. On one hand, researchers have tried to determine whether self-compassion can predict the different roles taken on in harassment dynamics. They have unanimously found that there is a negative association between self-compassion and the probability of being involved in the role of victim or aggressor (Fasihi & Abolghasemi, 2017; Geng & Lei, 2021; Múzquiz et al., 2021; Zăbavă, 2020). On the other hand, researchers have tried to determine whether self-compassion can buffer the harmful effects of bullying. Two studies carried out with samples of Chinese adolescents found that self-compassion played a key role in preventing depressive symptomatology after suffering bullying and when coping with cyberbullying (Q. Chen & Zhu, 2021; Zhang et al., 2019). According to a retrospective study by Beduna et al. (2019), participants showing low levels of self-compassion who had been harassed were more likely to develop shame in adulthood.

A series of studies that looked at bullying as one of the ways used to discriminate against students of racial and sexual minorities in the US (Vigna et al., 2018, 2020) found that self-compassion had a positive effect on resilience against discrimination. However, some nuances were identified, that is once the levels of victimization were controlled in the analysis, situations of high structural discrimination required high levels of self-compassion in order to boost resilience. It is important to note that although some studies point to higher victimization of cultural and sexual minorities, their predictive value is low (Llorent et al., 2016). That is, many non-minority students are also frequently harassed and bullying can be harmful on its own regardless of any specific discrimination. That is why it is relevant to research the direct effect that the different types of bullying can have on the well-being of adolescents, as well as the role that self-compassion can play as a protective variable. No prior research has studied if self-compassion may buffer the negative effects that relational and direct bullying can have on emotional well-being.

Given that self-compassion appears to be associated with resilience and emotional well-being, we hypothesize, first, that there will be a negative association between both types of bullying (direct and relational) and emotional well-being, and second, that self-compassion will have a positive association with well-being and will foster emotional well-being among those who suffer either type of bullying (direct or relational).

Method

Participants

Participants included 433 adolescents (49% male and 51% female, Mage = 13.28; SD = 0.72, range 12–14). The sample consisted of Spaniards (76.9%), South Americans (11%), non-Spanish Europeans (6%), Africans (2.5%), and Asians (1.6%). Just 1% of the participants did not report their place of birth (see Table 1). The sample was a non-randomized intentional sample. Members of different schools attended a three-day course about bullying in Madrid, after which they were invited to participate in the study. Of those contacted, two public and two charter schools of this city accepted to take part in it.

Adolescents and parents’ approvals were obtained by sending out a school-wide letter. Confidentiality and anonymity were assured. Data were only collected from students whose parents had read the letter. This procedure has been followed in similar studies with adolescents. The school boards of the four participating schools and the ethic committee of the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED) approved the study.

Students answered the questionnaires in their own class. A psychologist and a research assistant oversaw data collection. Before starting the tests, the psychologist read standard instructions aloud.

Participants were also informed that all the answers were anonymous and confidential. Likewise, they were assured that the results would only be used for research purposes. The students gave informed consent for participating by filling in the questionnaire. No time limit was prescribed. However, the majority answered in an average time of 25–30 min.

Enrolled schools received a workshop on bullying for teachers and/or students. The pupils also participated in a lottery for cinema or theater tickets.

Measures

Sociodemographic variable

Students were requested to provide some sociodemographic information, which included their gender, age, grade, place of birth, with whom they usually live, their parents or guardians’ place of birth, education level, and occupation.

Self-Compassion Scale (SCS, Neff, 2003 Spanish version of García-Campayo et al., 2014)

Participants were given the 26-item scale. The SCS includes six subscales: Self-kindness (e.g., “I try to be loving towards myself when I’m feeling emotional pain”), Self-judgement (e.g., “I’m disapproving and judgmental about my own flaws and inadequacies”), Common humanity (e.g., “I try to see my failings as part of the human condition”), Isolation (e.g., ‘‘When I think about my inadequacies it tends to make me feel more separate and cut off from the rest of the world’’), Mindfulness (“When something painful happens I try to take a balanced view of the situation”), and Over-identification (e.g., “When I’m feeling down I tend to obsess and fixate on everything that’s wrong’’). Responses were given on a five-point Likert-scale that ranged from one (“Almost Never”) to five (“Almost Always”). Mean scores on the six subscales were summed (once the negative items – self-judgement, isolation and over-identification – had been inverted) to obtain the total score on the scale that was used in the present study.

Internal consistency for the scale has been found to be good on the original scale (Neff, 2003), in a sample with American adolescents (Neff & McGehee, 2010), and with Spanish samples (García-Campayo et al., 2014; Játiva & Cerezo, 2014). Internal consistency for the scale in the present study (measured by Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.84.

Relational and direct bullying victimization

The items were based on the revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Participants were asked how frequently they were involved as victims in different forms of bullying. Direct bullying was measured by four items, two of them referring to physical bullying (“I have been kicked, hit or pushed”, “I had things taken away from me or damaged”); and two referring to verbal bullying (“I have been intimidated or threatened” and “I have been called mean and hurtful names”). Four items measured Relational bullying victimization (“Other students ignored me on purpose,” “I was rejected by other students,” “Other students did not let me participate in groups and activities,” and “Other students told lies or spread false rumors about me and tried to make others dislike me”). Internal consistency for the scale in the present study (measured by Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.79.

Positive Affect and Negative Affect

Were assessed with the Spanish Version for Children and Adolescents (PANASN; Sandín, 2003) of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, et al., 1988). Participants answered the full, 20-item version. On a five-point scale, they were asked to rate the frequency with which they had experienced… Positive Affect (PA) and Negative Affect (NA) within the last two months. The Spanish version showed good levels of reliability for Positive (α = 0.72) and Negative (α = 0.75) Affect (Sandín, 2003). Reliability of the scale in the present study (measured by Cronbach’s alpha) was PA = 0.75 and NA = 0.84.

Data analysis

All analyses were performed with SPSS v22 (IBM Corporation, New York, NY, USA). To examine the relationship between different types of bullying, NA, and PA, different bivariate correlational analyses were conducted.

To study the potential mediating effect that self-compassion could have between relational and direct bullying and positive and negative affect the Baron and Kenny (1986) procedure was followed. The procedure requires four conditions. First, the independent variable (relational and direct bullying) must have a significant correlation with the mediating variable (self-compassion). Second, the mediating variable has a significant relation with the dependent variable (positive affect, negative affect). Third, there exists correlation between the independent variable and the outcome variable. Finally, the association between the latter two variables decreases when the mediating variable is part of the regression model. Therefore, four linear regression analyses were performed depending on the type of bullying (direct and relational) and the measure of affect taken into consideration (PA, NA). The Sobel approach (Sobel, 1982) was performed to test the significance of all the mediation effects.

Results

Preliminary analysis

Firstly, it was tested if there were differences based on gender. Boys scored significantly higher in self-compassion than girls [F(1, 431) = 24.33, p < 0.05; d = 0.30] (M = 3.28; SD = 0.48; M = 3.11; SD = 0.67, respectively). Boys also reported lower levels of negative affect than girls [F(1, 431) = 3.04 p < 0.05; d = 0.25] (M = 0.99; SD = 0.65; M = 1.16; SD = 0.76, respectively). However, the analyses did not show any differences in positive affect, relational or direct bullying.

Correlations among the studied variables

Table 2 shows the correlations among direct bullying, relational bullying, self-compassion, positive affect, and negative affect. Those participants, who reported suffering relational bullying more frequently, tended to express higher negative affect, and were more likely to suffer direct bullying. There was also a significant negative correlation between relational bullying and positive affect, but these two variables shared only 2% of the variance.

Direct bullying had a positive correlation with negative affect. Being a victim of direct bullying had a negative correlation with self-compassion.

Self-compassion had a positive correlation with positive affect and a negative correlation with negative affect. Self-compassion explained a higher percentage of the variance in the case of negative affect (32.5%) than it did with positive affect (11.6%).

Self-compassion as a mediator between being a victim of bullying and emotional well-being

Although there were differences in self-compassion and negative affect depending on gender, analyses showed that gender did not contribute significantly to any of the regression models (in all standardized beta p > 0.25). Therefore, it was used the total sample in the subsequent analyses.

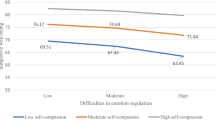

Four regression models were tested to study the role of self-compassion between relational and direct bullying and positive and negative affect. Results of the three significant models are shown in Fig. 1.

Self-compassion partially mediated the relationship between both types of bullying (direct and relational) and negative affect. Likewise, self-compassion totally mediated the association between relational bullying and positive affect. For all cases, Sobel test was significant (p < 0.001) (see Table 3).

Discussion

This study sought to explore the potential mediator effect that self-compassion might have between suffering bullying (relational or direct) and emotional well-being. We expected to find a negative association between suffering either type of bullying (direct and relational) and emotional well-being, as well as a negative association between both forms of victimization and self-compassion. We also sought to confirm a strong correlation between self-compassion and emotional well-being. Consistent with extant literature, findings from this research suggest that self-compassion is a protective factor of the emotional well-being of individuals subject to bullying.

In order to test this main hypothesis firstly it was explored the association between different types of bullying (direct or relational) and emotional well-being. Results showed that being a victim of relational bullying had a stronger negative correlation with emotional well-being (positive and negative affect) than direct bullying. Relational bullying, in comparison to direct bullying, also had a negative correlation with positive affect besides its correlation with negative affect. These results are according to other research that found transnationally that subjective well-being of children over 10 tended to feel more affected by psychological bullying than to physical bullying (Savahl et al., 2019). However, the mentioned studied just compared being hit versus being left out. The present study extends the literature in this field with two more complete measures of relational and direct bullying. These results suggest that being intentionally isolated from peers impairs the capacity of adolescents to feel positive emotions such as enthusiasm or joy, besides the negative emotions that they already might be experiencing (i.e., anger or fear). It is worth noting this result because teachers tend to identify and intervene more easily when bullying is direct or physical than when it is relational (L. Chen et al., 2018). The harmful impact of relational bullying on positive affect should be taken into consideration for further research, prevention and intervention models against bullying.

Secondly, according to extant literature, results supported the prediction of a negative association between different types of bullying and self-compassion (Fasihi & Abolghasemi, 2017; Geng & Lei, 2021; Múzquiz et al., 2021; Zăbavă, 2020). One possible interpretation is that growing up in a hostile peer environment may hinder the development of self-compassion and erode the capacity of treating oneself kindly. This is an inspiring finding because, although there is research on the topic of how attachment and family acceptance may influence self-compassion (Gilbert & Irons, 2005), studies about how the relation with peers affects self-compassion levels during adolescence are scarce. Future longitudinal analyses will help clarify the way relation with peers affect self-compassion and vice versa.

Additionally, the current study adds evidence to the relationship between self-compassion and emotional well-being in a large Spanish adolescent sample. This finding is consistent with extant literature that has found self-compassion to be associated with indicators of well-being and satisfaction (Baer et al., 2012; Bluth et al., 2017; Y. Chen et al., 2016; Neff et al., 2007).

Finally, we examined the mediating role that self-compassion may have between being a victim of bullying (relational and direct) and emotional well-being (positive and negative affect). Our results showed that self-compassion was a partial mediator between being a victim of bullying (either relational or direct) and negative affect. These results are congruent with existing literature that found self-compassion to be a mediator between peer victimization or traumatic stress and depression, self-injury or psychological maladjustment among adolescents (Játiva & Cerezo, 2014; Jiang et al., 2016; Xavier et al., 2016; Zeller et al., 2015). This result is also coherent from a theoretical perspective since psychopathological symptoms as well as psychological distress are derived from self-criticism, and self-compassion may be a powerful antidote against self-criticism (Gilbert & Irons, 2009). This is an encouraging finding given that self-compassion can be trained and changes in self-compassion may be associated with changes in anxious and depressive symptomatology (Edwards et al., 2014; Galla, 2016; Hoffart et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2019).

The present study had two important limitations. First, it was a correlational study. Self-compassion may ameliorate the effects of bullying on well-being, but it could also be that students who have higher levels of emotional well-being tend to report higher self-compassion levels. Second, it was based on self-report measures. Consequently, respondent bias could have influenced the associations found. For example, high self-compassionate individuals may find some aggressions as part of the normal middle school student experience; meanwhile low self-compassionate individuals may consider normal conflicts as bullying. Hence, longitudinal, experimental analysis and studies based on other informants (peer, parents, and teachers) measures would offer a better understanding of the interrelation among these variables.

In summary, the present study increases the knowledge about the relationship among bullying, well-being and self-compassion in adolescents. It also gives support to the idea that relational bullying may have even more harmful effects than direct bullying. Moreover, it extends the knowledge about how relationships with peers may influence self-compassion. Furthermore, the present research extends the scarce literature about how self-compassion may mediate the effects of bullying, especially in the early adolescence and extends the literature that self-compassion may be a useful component in intervention and prevention models.

Data availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Archer, J., & Coyne, S. M. (2005). An integrated review of indirect, relational, and social aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(3), 212–230. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0903_2

Baer, R. A., Lykins, E. L., & Peters, J. R. (2012). Mindfulness and self-compassion as predictors of psychological wellbeing in long-term meditators and matched nonmeditators. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(3), 230–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2012.674548

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Beduna, K. N., & Perrone-McGovern, K. M. (2019). Recalled childhood bullying victimization and shame in adulthood: The influence of attachment security, self-compassion, and emotion regulation. Traumatology, 25(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000162

Biswas, T., Scott, J. G., Munir, K., Thomas, H. J., Huda, M. M., Hasan, M. M., David de Bries, T., Baxter, J., & Mamun, A. A. (2020). Global variation in the prevalence of bullying victimisation amongst adolescents: Role of peer and parental supports. EClinicalMedicine, 20, 100276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100276

Björkqvist, K. (1994). Sex differences in physical, verbal, and indirect aggression: A review of recent research. Sex Roles, 30(3–4), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01420988

Bluth, K., & Blanton, P. W. (2015). The influence of self-compassion on emotional well-being among early and older adolescent males and females. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(3), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.936967

Bluth, K., Campo, R. A., Futch, W. S., & Gaylord, S. A. (2017). Age and gender differences in the associations of self-compassion and emotional well-being in a large adolescent sample. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(4), 840–853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0567-2

Chen, L., Wany, L., & Sung, Y. (2018). Teachers’ recognition of school bullying according to background variables and type of bullying. Educational, Cultural and Psychological Studies Journal, 18(1), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.7358/ecps-2018-018-chen

Chen, Q., & Zhu, Y. (2021). Cyberbullying victimisation among adolescents in China: Coping strategies and the role of self-compassion. Health & Social Care in the Community. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13438

Chen, Y., Peng, Y., & Fang, P. (2016). Emotional intelligence mediates the relationship between age and subjective well-being. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 83(2), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415016648705

Denckla, C. A., Consedine, N. S., & Bornstein, R. F. (2017). Self-compassion mediates the link between dependency and depressive symptomatology in college students. Self and Identity, 16(4), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2016.1264464

Diener, E., Scollon, C. N., & Lucas, R. E. (2009). The evolving concept of subjective well-being: The multifaceted nature of happiness In E Diener. Assessing well-being Social Indicators Research Series, 39, 67–100.

Dreisoerner, A., Junker, N. M., & Van Dick, R. (2020). The relationship among the components of self-compassion: A pilot study using a compassionate writing intervention to enhance self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22, 21–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00217-4

Edwards, M., Adams, E. M., Waldo, M., Hadfield, O., & Biegel, G. M. (2014). Effects of a mindfulness group on Latino adolescent students: Examining levels of perceived stress, mindfulness, self-compassion, and psychological symptoms. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 39(2), 145–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2014.891683

Fasihi, A., & Abolghasemi, A. (2017). The comparison of emotional processing and self-compassion in bully and victim students. International Journal of Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Science, 6(2), 86–95.

Ferrari, M., Hunt, C., Harrysunker, A., Abbott, M. J., Beath, A. P., & Einstein, D. A. (2019). Self-compassion interventions and psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis of RCTs. Mindfulness, 10(8), 1455–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01134-6

Galla, B. M. (2016). Within-person changes in mindfulness and self-compassion predict enhanced emotional well-being in healthy, but stressed adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 204–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.016

García-Campayo, J., Navarro-Gil, M., Andrés, E., Montero-Marín, J., López-Artal, L., & Demarzo, M. M. P. (2014). Validation of the Spanish versions of the long (26 items) and short (12 items) forms of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-4

Geng, J., & Lei, L. (2021). Relationship between stressful life events and cyberbullying perpetration: Roles of fatalism and self-compassion. Child Abuse & Neglect, 120, 105176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105176

Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2009). Shame, self-criticism, and self-compassion in adolescence. Adolescent Emotional Development and the Emergence of Depressive Disorders, 1, 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511551963.011

Hayden, E.P., & Mash, E.J. (2014). Child psychopathology: A developmental-systems perspective. In E.J. Mash & R.A. Barkley RA (Eds.), Child psychopathology (pp. 3–72). The Guilford Press.

Hoffart, A., Øktedalen, T., & Langkaas, T. F. (2015). Self-compassion influences PTSD symptoms in the process of change in trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapies: A study of within-person processes. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1273. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01273

Idsoe, T., Vaillancourt, T., Dyregrov, A., Hagen, K. A., Ogden, T., & Nærde, A. (2021). Bullying victimization and trauma. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 1602. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.480353

Játiva, R., & Cerezo, M. (2014). The mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between victimization and psychological maladjustment in a sample of adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(7), 1180–1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.04.005

Jiang, Y., You, J., Hou, Y., Du, C., Lin, M., Zheng, X., & Ma, C. (2016). Buffering the effects of peer victimization on adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: The role of self-compassion and family cohesion. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.09.005

Lahtinen, O., Järvinen, E., Kumlander, S., & Salmivalli, C. (2020). Does self-compassion protect adolescents who are victimized or suffer from academic difficulties from depression? European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 17(3), 432–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2019.1662290

Lennarz, H. K., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., Timmerman, M. E., & Granic, I. (2018). Emotion differentiation and its relation with emotional well-being in adolescents. Cognition and Emotion, 32(3), 651–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2017.1338177

Lereya, S. T., Copeland, W. E., Costello, E. J., & Wolke, D. (2015). Adult mental health consequences of peer bullying and maltreatment in childhood: Two cohorts in two countries. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(6), 524–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00165-0

Llorent, V. J., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Zych, I. (2016). Bullying and cyberbullying in minorities: Are they more vulnerable than the majority group? Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1507. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01507

MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 545–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003

Marsh, I. C., Chan, S. W. Y., & MacBeth, A. (2018). Self-compassion and psychological distress in adolescents - a meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 9(4), 1011–1027. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0850-7

Marshall, S. L., Parker, P. D., Ciarrochi, J., Sahdra, B., Jackson, C. J., & Heaven, P. C. (2015). Reprint of “Self-compassion protects against the negative effects of low self-esteem: A longitudinal study in a large adolescent sample.” Personality and Individual Differences, 81, 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.049

Moon, S. S., Kim, H., Seay, K., Small, E., & Kim, Y. K. (2016). Ecological factors of being bullied among adolescents: A classification and regression tree approach. Child Indicators Research, 9(3), 743–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-015-9343-1

Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., & Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(1), 60–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60

Múzquiz, J., Pérez-García, A. M., & Bermúdez, J. (2021). Self-esteem, self-compassion and positive and negative affect in victims and bullies: A comparative study with self-report and peer-report measures. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Psychology / Revista De Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 26(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.28156

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L., & Rude, S. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/e527772014-669

Neff, K. D., & McGehee, P. (2010). Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self and Identity, 9(3), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860902979307

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Blackwell Publishers.

Patton, G. C., Olsson, C. A., Skirbekk, V., Saffery, R., Wlodek, M. E., Azzopardi, P. S., Stonawski, M., Rasmusen, B., Spry, E., Francis, K., Bhutta, Z. A., Kassebaum, N. J., Mokdad, A. H., Murray, C. J. L., Prentice, A. M., Reavley, N., Sheehan, P., Sweeny, K., Viner, R. M., & Sawyer, S. M. (2018). Adolescence and the next generation. Nature, 554(7693), 458–466. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25759

Phillips, W. J. (2019). Self-compassion mindsets: The components of the self-compassion scale operate as a balanced system within individuals. Current Psychology, 40, 5040–5053. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00452-1

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007

Sandín, B. (2003). The PANAS Scales of Positive and Negative Affect for children and adolescents (PANASN). Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Psychology/ Revista De Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 8(2), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.vol.8.num.2.2003.3953

Savahl, S., Montserrat, C., Casas, F., Adams, S., Tiliouine, H., Benninger, E., & Jackson, K. (2019). Children’s experiences of bullying victimization and the influence on their subjective well-being: A multinational comparison. Child Development, 90(2), 414–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13135

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312. https://doi.org/10.2307/270723

Susman, E. J., & Dorn, L. D. (2013). Puberty: Its role in development. In R. M. Lerner, M. A. Easterbrooks, J. Mistry, & I. B. Weiner (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Developmental psychology (pp. 289–320). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Vigna, A. J., Poehlmann-Tynan, J., & Koenig, B. W. (2018). Does self-compassion facilitate resilience to stigma? A school-based study of sexual and gender minority youth. Mindfulness, 9, 914–924. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0831-x

Vigna, A. J., Poehlmann-Tynan, J., & Koenig, B. W. (2020). Is self-compassion protective among sexual- and gender-minority adolescents across racial groups? Mindfulness, 11, 800–815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01294-5

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Wilson, A. C., Mackintosh, K., Power, K., & Chan, S. W. Y. (2019). Effectiveness of self-compassion related therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 10(6), 979–995. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1037-6

Xavier, A., Gouveia, J. P., & Cunha, M. (2016). Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence: The role of shame, self-criticism and fear of self-compassion. Child & Youth Care Forum, 45(4), 571–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-016-9346-1

Zăbavă, T. (2020). The compassion dimension in bullying in high school students. Journal of Experiential Psychotherapy, 23(3), 25–37.

Zeller, M., Yuval, K., Nitzan-Assayag, Y., & Bernstein, A. (2015). Self-compassion in recovery following potentially traumatic stress: Longitudinal study of at-risk youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(4), 645–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9937-y

Zhang, H., Chi, P., Long, H., & Ren, X. (2019). Bullying victimization and depression among left-behind children in rural China: Roles of self-compassion and hope. Child Abuse & Neglect, 96, 104072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104072

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. JM: designed and executed the study, assisted with the data analyses, and wrote the paper. APG: collaborated in the design of the study and writing of the paper. JB critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all individual participants.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Múzquiz, J., Pérez-García, A.M. & Bermúdez, J. Relationship between Direct and Relational Bullying and Emotional Well-being among Adolescents: The role of Self-compassion. Curr Psychol 42, 15874–15882 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02924-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02924-3