Abstract

In this study, we interpret codependency as a dysfunctional pattern of relating to others, and based on this approach, we hypothesized an association with negative forms of dyadic coping, relationship problems and life satisfaction. A total of 246 Hungarian participants (167 females, 79 males), aged 18–72 years (M = 35.3, SD = 11.6) completed our online survey including measures of codependency, dyadic coping, perceptions of relationship, and life satisfaction. In our cross-sectional research, the Spann-Fischer Codependency Scale (SF-CDS), the Dyadic Coping Inventory (DCI), the Shortened Marital Stress Scale (MSS-R), and the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) were used. Correlational and pathway analyzes were applied to confirm our hypotheses. Codependency was associated with negative dyadic coping, while we found no measurable influence on positive dyadic coping. Individuals with higher codependency rated both their own and their partner’s negative dyadic coping more pronounced, while at the same time they characterized their relationships as more problematic. Structural Equation Modelling proved that codependent attitudes, along with the emergence of negative dyadic coping forms and perception of relationship problems, reduce a person’s life satisfaction. Overall, it can be stated that the more codependent the participants were, the more negative their own and partner’s behaviour was perceived in stressful situations and the more problematic their intimate relationship was found to be. Our results support the idea that codependency is a specific, largely stable attitude that determines a person’s perception and behaviour relating to others.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The phenomenon of codependency was at first recognized as a typical enabling attitude of a family member (typically a wife or a mother) of a person suffering from chemical dependence. The term co-dependency comes from co-chemical dependency (Whitfield, 1984). According to the modern approach, codependency is not limited to relationships affected by addictions. Over the past few decades, there have been growing interest in the topic of codependency; however, there is still a lack of consensus on the definition. The divergent approaches include the personality model (Cermak, 1986; Fischer & Spann, 1991), the disease model (Whitfield, 1984), the addictive love hypothesis (Peele & Brodsky, 1975) and the interactionist model (Wright & Wright, 1991). In the present study, we use the personality model, which defines codependency as a dysfunctional pattern of personality organisation and relating to others (Cermak, 1986). Based on the personality model, Spann and Fischer (1990) created the working definition of codependency, which is the most widely used and comprehensive approach to date. According to this working definition, codependency is “a psychosocial condition manifested through a dysfunctional pattern of relating to others. This pattern is characterized by extreme focus outside of self, lack of open expression of feelings, and attempts to derive a sense of purpose through relationships.” (Spann & Fischer, 1990, p. 27). We committed ourselves to this definition since it acknowledges both the intrapsychic and interpersonal aspects of codependency (Cermak, 1986).

Previous studies identified correlations between codependency and several intrapsychic and relational features. Codependency was found to be correlating negatively with self-esteem (Martsolf et al., 2000; Stafford, 2001) and interpersonal control (Springer et al., 1998) and positively with various psychopathological conditions, such as covert narcissism (Wells et al., 2006), borderline and dependent personality disorders (Hoenigmann-Lion & Whitehead, 2007; Knapek et al., 2017) as well as depression (Hughes-Hammer et al., 1998). Furthermore, codependency is associated with a wide variety of relationship problems. For example, in a previous study, individuals with high codependency scores reported greater difficulties in their relationships in the areas of communication, roles, involvement, expression of emotions and issues of control, values, and norms (Cullen & Carr, 1999). Codependent wives were proved to have fewer coping resources and less social support than non-codependent wives (Bhowmick et al., 2001). Another research reported problems of differentiation – according to Bowen’s (1978) concept – among codependent individuals (Lampis et al., 2017). Moreover, results revealed that differentiation of self was in stronger connection with codependency than dyadic adjustment. Amongst the dimensions of dyadic adjustment, satisfaction and dyadic cohesion did not relate to codependency, but positive correlation was found with affective expression (Lampis et al., 2017). Even though, as far as we know, preceding studies did not address the relationship between codependency and dyadic coping, data supporting the correlation between relating concepts are available. As Cowan et al. (1995) found, individuals with higher codependency were more likely to use indirect strategies (Falbo & Peplau, 1980) to enforce their will, in both interactive and non-interactive forms. Furthermore, regarding positive and negative attitudes towards the partner, codependency showed no correlation with caring for or supporting the partner, however showed positive correlation with being competitive with the partner (Springer et al., 1998).

Based on Bodenmann’s theory (1995, 1997a, b), dyadic stress is a stressful event that affects both partners in a relationship, whether directly or indirectly, and forces them to start coping efforts. In addition to individual efforts, partners also make dyadic efforts using problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies, motivated by their interdependence, common concerns, and common goals. Dyadic coping does not replace the process of individual coping, but the two coping paths function simultaneously (Bodenmann, 2000). According to the Systemic Transactional Model (STM) (Bodenmann, 1995), which interprets the general processes of couples’ everyday stress situations, individual goals foster individual coping, while common goals promote dyadic coping. Dyadic coping is considered not to be an altruistic behaviour, as the satisfaction and well-being of the partner influences one’s satisfaction and well-being, as well as relationship quality (Bodenmann, 1995). Dyadic coping can take both positive and negative forms. We consider the supportive, delegated and common dyadic coping strategies to be positive. Supportive dyadic coping means that one helps their partner to cope. In the case of common (or joint) dyadic coping, the partners work together to find a solution. Delegated dyadic coping is usually problem-focused, for example, one of the partners performs the task instead of the other. Negative dyadic coping strategies include hostile, ambivalent, and superficial ways of coping. Hostile dyadic coping includes behaviours such as ridiculing the partner, trivializing their problems or acting distant with them. Ambivalent dyadic coping means that although one supports their partner but does so unwillingly and without motivation. Superficial dyadic coping is an illusory cooperation, but not real support (Bodenmann et al., 2016). Negative forms of dyadic coping were more common in a clinical sample (Bodenmann, 2000). Successful dyadic coping affects psychological and physical well-being, relationship satisfaction (Bodenmann, 2000), life satisfaction (Gabriel et al., 2016), and feelings of ‘we-ness’, mutual trust, intimacy, and connectedness (Bodenmann, 2000; Falconier & Kuhn, 2019). Arrindell et al. (1991) found that while gender, age, and education did not affect life satisfaction, relationship status showed a clearly measurable result: those who were married or in a relationship, were more satisfied with their lives than single people. As mentioned earlier, successful dyadic coping also promotes individuals’ relationship satisfaction and life satisfaction (Bodenmann, 2000; Gabriel et al., 2016). Based on these previous results, we can assume that codependency has an effect on relationship functioning, and thus on dyadic coping strategies, but we do not know any previous research explicitly testing and analyzing the relationship between these variables. Furthermore, it is rewarding to use the framework of dyadic coping because it provides the opportunity to examine positive and negative dyadic coping behaviours simultaneously, as well as the individual’s perception of their own and their partner’s coping.

In this study, based on the theories and research results presented above, we hypothesised that individuals’ codependent functioning patterns affect negative dyadic coping as well as their perceptions of their relationships. We hypothesised that higher level of codependency is associated with the negative forms of dyadic coping (H1) and the perception of more relationship problems (H2), furthermore that codependency affects life satisfaction negatively through negative dyadic coping and the perception of the relationship (H3).

Methodology

Participants

The criteria of participation included a minimum age of 18 years and being in an intimate relationship. Participants were collected by convenience sampling, as many people meet the aforementioned criteria and we did not focus on any specific participant groups. The link to the questionnaire package was distributed on social media sites and participants were asked to complete it online (Google Forms). Participants were briefly informed through social media posts and detailed information about the research was given on the beginning page of the survey which they could read before giving their consent. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, by accepting the terms and conditions. Exclusion criteria were being younger than 18 years and not being in an intimate relationship at the time of participating, and there were screening questions to check the eligibility. One participant not giving consent was automatically excluded. The data were collected anonymously, and respondents did not receive any rewards or payment for participation. The research was approved by the Hungarian United Ethical Review Committee for Research in Psychology. Data were collected from October 2019 to June 2020. Participants completed each questionnaire once. They were asked about their age, education, and the type and duration of their existing intimate relationship. 246 Hungarian participants (167 females, 79 males), aged 18–72 years (M = 35.3, SD = 11.6) completed the questionnaires. 123 of them had higher education, 107 of them had secondary level education and 16 of them had only primary level education. At the time of completing the questionnaires, 95 people were married or lived in a registered partnership, 86 people were living with a partner, 50 people were in a committed relationship but living in separate households, and 15 people were in a non-committed relationship. 95 of the participants had lived in a relationship lasting 1–5 years, 67 of them 6–15 years, and 56 more than 15 years, with only 15 reporting a relationship lasting less than a year.

Materials

Spann-Fischer Codependency Scale (SF-CDS)

The SF-CDS (Fischer & Spann, 1991; Hungarian adoption is in progress) is a unidimensional self-report instrument for measuring codependency. The questionnaire contains 16 items and uses a 6-point Likert scale. Items relate to the person’s attitude towards self and others, e.g. “I seem to have relationships where I am always there for them but they are rarely there for me.” The higher the score on the scale, the higher the degree of codependency. In the present sample the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79.

Dyadic Coping Inventory (DCI)

The DCI contains 37 items (Bodenmann, 2008; Hungarian adaptation: Martos et al., 2012), and uses a 5-point Likert scale. Items relate to handling stressful situations in the existing intimate relationship of the person, e.g. “I try to analyze the situation together with my partner in an objective manner and help him/her to understand and change the problem”, “I provide support, but do it so unwillingly and unmotivated because I think that he/she should cope with his/her problems on his/her own”, or “We help one another to put the problem in perspective and see it in a new light.” The instrument includes nine subscales and five combined scales. The subscales are the following: Stress Communication by Oneself (SCO), Supporting Dyadic Coping by Oneself (SDCO), Delegated Dyadic Coping by Oneself (DDCO), Negative Dyadic Coping by Oneself (NDCO), Stress Communication by Partner (SCP), Supporting Dyadic Coping by Partner (SDCP), Delegated Dyadic Coping by Partner (DDCP), Negative Dyadic Coping by Partner (NDCP), and Common Dyadic Coping (GDC). The present research discusses the Negative Dyadic Coping by Oneself (NDCO) and Negative Dyadic Coping by Partner (NDCP) subscales, and the DCI Common Negative Dyadic Coping (NDCtot) combined scale which is a summary of the NDCO and NDCP subscales. For the subscales discussed, the higher score the participants reach, the more often they perceive negative dyadic forms of coping (hostile, ambivalent, superficial dyadic coping) as characteristics of themselves (NDCO), their partners (NDCP), and their relationships (NDCtot). The Cronbach’s alpha of the Dyadic Coping Scale (DCItot, 35 items) was 0.94, while that of the discussed subscales were 0.72 (NDCO) and 0.80 (NDCP), and that of the NDCtot combined scale was 0.81.

Shortened Marital Stress Scale (MSS)

We used 15 items from the MSS (Orth-Gomér et al., 1997; Hungarian adaptation: Balog et al., 2006); the 2 items that apply only to patients with coronary disease had been removed. Respondents had to give yes or no answers. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.75 for the shortened scale. The MSS Problem factor we are discussing contains 4 items, and its Cronbach’s alpha was 0.71. Items of this factor relate to the problematic nature of the intimate relationship, e.g. “Have you had serious problems in the relationship with your spouse currently?” The more times participants responded yes to the Problem factor questions, the more they rated their current intimate relationship as problematic. Other factors of the MSS scale are Love and Trust, Sexuality, and Personal Identity.

Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS)

The SWLS (Diener et al., 1985; Hungarian adaptation: Martos et al., 2014) contains 5 items, and uses a 7-point Likert scale. Items refer to the perception of life as being satisfying, e.g. “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing.” A higher score on the scale indicates a higher level of satisfaction with one’s life. The Cronbach’s alpha of the SWLS was 0.83 in the present study.

Data Analysis

To test our hypotheses, we performed correlation analyses using jamovi, a statistical spreadsheet, version 1.2.27.0 for macOS (The Jamovi Project, 2020). Structural Equation Modelling was performed using another statistical software program named JASP, version 0.14 for macOS (JASP Team, 2020). To evaluate model fit, we used the chi-square, the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). As acceptance criteria, the following were examined: a chi-square to df ratio (χ2/df) lower than 3.0, CFI and TLI values equal to or greater than 0.95 (Hu & Bentler, 1998), and RMSEA value equal to or lower than 0.08 (Browne & Cudeck, 1992).

Results

Correlations between Codependency (CD) and subscales of Dyadic Coping Inventory including Negative Dyadic Coping by Oneself (NDCO), and Negative Dyadic Coping by Partner (NDCP) (see Table 1) were significant, as we had hypothesised. These two subscales (NDCO & NDCP) together form the DCI Common Negative Dyadic Coping (NDCtot) summary scale. For better manageability we use this variable (NDCtot) in further discussion. Codependency showed a strong positive correlation with the MSS Problem factor and was negatively correlated with life satisfaction. As shown in Table 1, both the negative dyadic coping variables and the MSS Problem factor were negatively correlated with life satisfaction. Codependency did not show a significant correlation with any of the positive subscales of dyadic coping, nor with the other factors of the MSS scale.

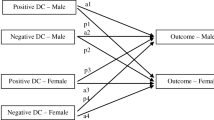

Thus, hypotheses H1 and H2 were confirmed. We examined hypothesis H3 by structural equation modelling (SEM). We first assumed and examined a model in which codependency influences negative dyadic coping, which affects satisfaction with life through MSS Problem factor (CD – > NDCtot – > MSS Problem – > SWLS), but the fit of this model did not prove to be adequate (see Table 2). Therefore, according to Modification Indices, we considered the direct relationships between the perception of codependency and the problematic nature of the relationship, as well as between common negative coping and life satisfaction. The modified model (Fig. 1) proved to be appropriate (Table 2). The test yielded a good model fit (Χ2(1) = 2.125, p = 0.145, TLI = 0.973, CFI = 0.996, RMSEA = 0.068, 90%CI = [0.00 – 0.2], SRMR = 0.019). The AIC and BIC values were lower in this model, confirming a better model fit also.

Model 2. Direct and indirect pathways between Codependency, Common Negative Dyadic Coping, Problems, and Life Satisfaction. CD = Codependency, NDCtot = Common Negative Dyadic Coping (NDCO&NDCP), MSS Problem = Problem Scale of Shortened Marital Stress Scale, SWLS = Satisfaction With Life Scale; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

The explanatory power of the model continuously increases up to the MSS Problem variable, and then decreases when the SWLS is reached. This result is interpreted in the discussion.

Discussion

The statistical analysis confirmed our hypothesis that codependent pattern affects the functioning of the relationship and its perception in a specific way. As seen in the results, codependency was not associated with the perception of positive forms of dyadic coping (common, supportive and delegated coping) in their relationships. Therefore, it can be assumed that individuals with higher codependency utilize positive forms of dyadic coping, and perceive such positive forms of coping in their partners, in the same way as less codependent people. This result meets the results of Springer et al. (1998) according to which codependency was not correlated with supporting the partner. Low self-esteem (Martsolf et al., 2000; Stafford, 2001) may encourage codependent people committing to positive dyadic coping forms because of getting positive external confirmation. We also found that people with higher codependency tended to rate their own and their partners’ negative dyadic coping (ambivalent, superficial and hostile) more pronounced. Thus, codependency as a specific pattern of relating to others amplifies the problems in the intimate relationship, without affecting the positive forms of cooperation. We can find logical explanations for these results referring to personality psychology theories and the Family Systems Theory (Kerr & Bowen, 1988). Regarding the etiology of codependency several empirical data suggest that the major factor in the background of codependency is a dysfunctional family of origin (eg: Prest & Protinsky, 1993; Cullen & Carr, 1999; Fuller & Warner, 2000). According to Family Systems Theory, dysfunctional relationship patterns are transmitted in an intergenerational way (Kerr & Bowen, 1988). During their childhood codependent people – as a reaction to the dysfunctional family functioning – learned to adapt to these dysfunctional family dynamics (Prest & Protinsky, 1993) and learned to cope in maladaptive ways to maintain the –pathological – balance. Growing up, these dysfunctional patterns are carried on into their intimate relationships affecting relationship functioning, including dyadic coping.

Results draw the attention to the specific functioning of codependent individuals, confirming that they are sensitive to negative feedback and susceptible to experiencing anxiety and vulnerability. The negative dyadic coping behaviours described in our results can be considered as efforts aimed solely at maintaining the relationship (ambivalent coping) or ways of exercising power indirectly (Cowan et al., 1995), competing their partners (Springer et al., 1998) as well as responding to the person’s own feelings of vulnerability (hostile coping and superficial coping). Thus, codependence causes the person's own negative behaviour in dyadic coping situations, which may be a way of strengthening the feeling of control.

This is also confirmed by the results that codependency has a significant direct influence on perceiving one’s relationship as problematic. According to the Family Systems Theory (Kerr & Bowen, 1988), this can be explained by growing up in a family environment where problems were present as a norm and coping situations were laden with conflicts. As Kerr and Bowen (1988) found, individuals with less differentiated self – which is associated with higher codependency – are more likely to experience relational anxiety and function less effectively in stressful situations. In the present study, we did not examine how often and to what extent participants experience stress in their relationships, however, considering the cited research results it is also possible that individuals with higher codependency tend to evaluate several situations as stressful events that others do not. We may also assume that codependent people are indeed facing many relationship problems because they have a distinctive pattern for choosing a partner with problematic behaviour—but in the present research the problematic behaviour of the partner was not examined. We reported no correlations between codependency and other factors of MSS (Love-Trust, Sexuality, and Personal Identity), which reaffirms our results that codependency has no measurable effect on the perception of positive relationship functioning. Nevertheless, methodological issues could also contribute to this result: namely, that Personal Identity and Sexuality factors include only two items.

Our model’s explanatory power decreased when SWLS was included, since life satisfaction is also influenced by several other factors, such as health status, self-confidence, neuroticism, well-being (Arrindell et al., 1999), optimism, or anxiety (Hinz et al., 2018). The negative correlation between codependency and life satisfaction may also be affected by characteristics that appear in a person’s other (not intimate) relationship. Negative dyadic coping perceived from the partner showed a stronger correlation with life satisfaction than the own negative dyadic coping. Accordingly, the partner's behaviour and cooperation have stronger effect on life satisfaction compared to that of one’s own. This result is firmly consistent with the definition of codependency, which states that codependent persons are characterized by extreme focus outside of self and they attempt to derive a sense of purpose through relationships (Spann & Fischer, 1990).

To sum up, codependency as a dysfunctional pattern of relating to others plays an important role in one’s relationship functioning, thus also in dyadic coping, influencing the perception of dyadic coping behaviour in a specific way. Our results suggest that both in terms of couples’ behaviour and the quality of the relationship codependency promotes more frequent presence and/or perception of problems. On the other hand, codependency has no effect on the positive dyadic coping behaviours. Results support the theory that codependency is a specific, largely stable attitude that determines a person’s perception and behavior relating to others.

Results can be applied in clinical practice, both in individual and couples’ therapy. Recognition of the codependent attitude can help the client to explore and interpret the characteristic patterns related to it, which gives the client the opportunity to recognize the consequences of their own behaviour and change their behavioural habits.

The study had also some limitations. Because of convenience sampling method, a large number of the participants were women with higher level of education which limits the generalizability of our results. The study was based on self-report measures that may have been open to response bias. Considering the gender differences in dyadic coping behaviours (e.g. Hilpert et al., 2016; Martos et al., 2012) future studies are needed to address gender differences in the relationship between codependency, dyadic coping and marital stress. Also codependency and dyadic coping could be examined for dyads, which would also allow the exploration of actor-partner effects (Kenny, 1996).

Availability of Data and Material

All data and materials as well as software application comply with field standards.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Arrindell, W. A., Meeuweesen, L., & Huyse, F. J. (1991). The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS): Psychometric properties in non-psychiatric medical outpatients sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 12(2), 117–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(91)90094-R

Arrindell, W. A., Heesink, J., & Feij, J. A. (1999). The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS): Appraisal with 1700 healthy young adults in The Netherlands. Personality and Individual Differences, 26, 815–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00180-9

Balog, P., Székely, A., Szabó, G., & Kopp, M. (2006). A rövidített házastársi stressz skála pszichometriai jellemzői. Mentálhigiéné És Pszichoszomatika, 7(3), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1556/Mental.7.2006.3.3

Bhowmick, P., Tripathi, B. M., Jhingan, H. P., & Pandey, R. M. (2001). Social support, coping resources and codependence in spouses of individuals with alcohol and drug dependence. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 43(3), 219.

Bodenmann, G. (1995). A systemic-transactional conceptualization of stress and coping in couples. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 54, 34–49.

Bodenmann, G. (1997a). Dyadic coping – a systemic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: Theory and empirical findings. European Review of Applied Psychology, 47, 137–140.

Bodenmann, G. (1997b). The influence of stress and coping on close relationships: A two-year longitudinal study. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 56, 156–164.

Bodenmann, G. (2000). Stress und Coping bei Paaren [Stress and coping in couples]. Hogrefe.

Bodenmann, G. (2008). Dyadisches Coping Inventar. Test Manual. Huber: Bern, Switzerland.

Bodenmann, G., Randall, A.K., & Falconier, M.K. (2016). Coping in couples: The Systemic Transactional Model (STM). In M.K. Falconier, A.K. Randall, & G. Bodenmann (Eds.), Couples coping with stress: A cross-cultural perspective (5–22). https://doi.org/10.3389/978-2-88963-031-8

Bowen, M. (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice. Jason Aronson.

Cermak, T. L. (1986). Diagnostic Criteria for Codependency. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 18(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.1986.10524475

Cowan, G., Bommersbach, M., & Curtis, S.R. (1995). Codependency, loss of self, and power. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19, 221–236. 10.1111%2Fj.1471–6402.1995.tb00289.x

Cullen, J., & Carr, A. (1999). Codependency: An empirical study from a systemic perspective. Contemporary Family Therapy, 21(4), 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021627205565

Diener, E., Emmons, E. R., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Falbo, T., & Q, & Peplau, L. A. (1980). Power strategies in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 618–628. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.38.4.618

Falconier, M.K. & Kuhn, R. (2019). Dyadic Coping in Couples: A Conceptual Integration and a Review of the Empirical Literature. In: Bodenmann, G., Falconier, M.K., Randall, A.K. (eds.) Dyadic Coping: A Collection of Recent Studies. Lausanne: Frontiers Media. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00571

Fischer, J. L., & Spann, L. (1991). Measuring codependency. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 8(1), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1300/J020V08N01_06

Fuller, J. A., & Warner, R. M. (2000). Family Stressors as Predictors of Codependency. Genetic, Social & General Psychology Monographs, 126(1), 5–22.

Gabriel, B., Untas, U., Lavner, J., Koleck, M., & Luminet, O. (2016). Gender typical patterns and the link between alexithymia, dyadic coping, and psychological symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences, 96, 266–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.029

Hilpert, P., Randall, A. K., Sorokowski, P., Atkins, D. C., Sorokowska, A., Ahmadi, K., & Yoo, G. (2016). The associations of dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction vary between and within nations: A 35-nation study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1106. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01106

Hinz, A., Conrad, I., Schroeter, M. L., Glaesmer, H., Brähler, E., Zenger, M., Kocalevent, R.-D., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2018). Psychometric properties of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), derived from a large German community sample. Quality of Life Research, 27(6), 1661–1670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1844-1

Hoenigmann-Lion, N. M., & Whitehead, G. I. (2007). The relationship between codependency and borderline and dependent personality traits. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 24(4), 55–77. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/https://doi.org/10.1300/J020v24n04_05

Hughes-Hammer, C., Martsolf, D. S., & Zeller, R. A. (1998). Depression and codependency in women. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 12(6), 326–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9417(98)80046-0

Kenny, D. A. (1996). Models of nonindependence in dyadic research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13, 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407596132007

Kerr, M., & Bowen, M. (1988). Family evaluation: An approach based on Bowen theory. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

Knapek, É., Balázs, K., & Szabó, I. K. (2017). The substance abuser’s partner: Do codependent individuals have borderline and dependent personality disorder? Addiction is a treatable disease. Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems, 19(5), 55–62.

Lampis, J., Cataudella, S., Busonera, A., & Skowron, E. A. (2017). The role of differentiation of self and dyadic adjustment in predicting codependency. Contemporary Family Therapy, 39(1), 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-017-9403-4

Martos, T., Sallay, V., Nistor, M., & Józsa, P. (2012). Párkapcsolati megküzdés és jóllét – a Páros Megküzdés Kérdőív magyar változata. [Dyadic coping and well-being—The Hungarian version of the Dyadic Coping Inventory]. Psychiatria Hungarica, 27 (6), 446–458.

Martos, T., Sallay, V., Désfalvi, J., Szabó, T., & Ittzés, A. (2014). Az Élettel való Elégedettség Skála magyar változatának (SWLS-H) pszichometriai jellemzői. [Psychometric characteristics of the Hungarian version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS-H)]. Mentálhigiéné és Pszichoszomatika, 15(3), 289–303. https://doi.org/10.1556/Mental.15.2014.3.9

Martsolf, D. S., Sedlak, C. A., & Doheny, M. O. (2000). Codependency and related health variables. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 14(3), 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1053/py.2000.6387

Orth-Gomér, K., Chesney, M. A., & Anderson, D.E. (1997): Social stress/strain and heart disease in women. In: Julian, D. G., Wenger, N. K. (eds.): Women and Heart Disease, Martin Dunitz, London, 407–420.

Peele, S., & Brodsky, A. (1975). Love and addiction. Signet.

Prest, L. A., & Protinsky, H. (1993). Family systems theory: A unifying framework for codependence. American Journal of Family Therapy, 21(4), 352–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926189308251005

Spann, L., & Fischer, J. L. (1990). Identifying codependency. The Counselor, 8, 27.

Springer, C. A., Britt, T. W., & Schlenker, B. R. (1998). Codependency: Clarifying the construct. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 20(2), 141–158.

Stafford, L. L. (2001). Is codependency a meaningful concept? Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 22(3), 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840121607

Wells, M. C., Hill, M. B., Brack, G., Brack, C. J., & Firestone, E. E. (2006). Codependency’s relation-ships to defining characteristics in college students. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 20(4), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1300/J035v20n04_07

Whitfield, C. L. (1984). Co-alcoholism: Recognizing a treatable illness. Family & Community Health: The Journal of Health Promotion & Maintenance, 7(2), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003727-198407020-00004

Wright, P. H., & Wright, K. D. (1991). Codependency: Addictive love, adjustive relating, or both? Contemporary Family Therapy, 13, 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00890497

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Pécs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Zsuzsa Happ, Zsófia Bodó-Varga, and Krisztina Csókási. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Zsuzsa Happ and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional Declarations for Articles in Life Science Journals that Report the Results of Studies Involving Humans and/or Animals

Not applicable.

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The research was approved by the Hungarian United Ethical Review Committee for Research in Psychology (16/12/2019; Nr. 2019–115). The data were collected anonymously, and respondents did not receive any rewards or payment for participation.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

There is no personal data or identifying information in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Highlights

Higher level of codependency is associated with the negative forms of dyadic coping

Codependency does not affect the perception of positive dyadic coping

Codependency promotes more frequent presence and/or perception of relationship problems

Codependent pattern affects the relationship and its perception in a specific way

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Happ, Z., Bodó-Varga, Z., Bandi, S.A. et al. How codependency affects dyadic coping, relationship perception and life satisfaction. Curr Psychol 42, 15688–15695 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02875-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02875-9