Abstract

The expression of prejudice has mutated over the last century, and most Western countries now legally support equality. However, for ethnic minorities, work discrimination is one of the most evident challenges they have to face. Three preregistered experiments, with an overall sample of 1,507 participants, analyzed the effect of a job applicant’s ethnicity and other characteristics (e.g., gender, attractiveness), which were manipulated with a CV, as well as possible moderator variables (tolerance and racism), on participants’ judgments about the candidate: stereotypes (competence, sociability, morality, and immorality); emotions (admiration, contempt, compassion, and envy); and active and passive facilitation tendencies at work. The results indicated that tolerance and racism modulated the effect of ethnicity on the dependent variables in an administrative occupation (Studies 1 and 2) and in the hostelry industry (Study 3). A pooled analysis revealed that egalitarian participants (high tolerance or low racism) reported an unexpected positive bias toward a Moroccan candidate compared to a Spanish candidate. Non-egalitarian participants (low tolerance or high racism) showed the expected ingroup bias only for (im)morality: they perceived Moroccan applicants as less moral and more immoral than Spanish candidates. Studies 2 and 3 confirmed that the Moroccan candidate was perceived as less prototypical of his/her category than the Spanish applicant was. We discussed the primacy of (im)morality in social perception as well as the relevance of distinguishing between egalitarian and non-egalitarian people when trying to understand the complexity of new expressions of prejudice and to identify strategies to avoid discrimination in the workplace.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Tempora mutantur, nos et mutamur in illis (the times change, and we change with them), and the expression of prejudice is not immune to that change. Distinct psychosocial models have tried to explain how contemporary forms of ethnic prejudice are currently expressed. Although contemporary Western societies are characterized by a normative promotion of egalitarian values, prejudice and ethnic discrimination still endure. Work discrimination is one of the most evident challenges that ethnic minorities have to face in contemporary societies (e.g., Conseil de la Communauté Marocaine à l’Étranger [CCME], 2020). However, the current expression of prejudice in the workplace cannot be reduced to simple hostile actions or negative evaluations toward minorities, but it encompasses a complex mixture of cognitive and motivational processes, often modulated by the perceiver’ value system.

Our research is intended to provide a comprehensive picture on contemporary labor discrimination of ethnic minorities. For this purpose, we consider how other basic features of the target (i.e., gender, attractiveness, professional and parental status), as well as the individuals’ value system can interact with the ethnicity of the target to conform cognitive, affective and behavioral responses toward people in the workplace. Specifically, the present research analyzes the effect of an applicant’s ethnicity and other characteristics (i.e., gender, attractiveness, professional and parental status; manipulated with a CV), as well as ideological moderators (tolerance and racism), on participants’ judgments about the candidate, including stereotypes (competence, sociability, morality, and immorality); emotions (admiration, contempt, compassion, and envy); and active and passive facilitation tendencies at work.

Complexity in the Expression of Prejudice

As Western societies have evolved toward promoting equality and minorities’ civil rights, the traditional expression of prejudice has also been transformed from blatant forms (open, negative, hostile discrimination) to more subtle and ambivalent expressions. These new forms of expression are generally characterized by attitudinal ambivalence triggered by people’s internal conflict between their pro-equality beliefs and their unconscious and uncontrollable negativity toward specific outgroups (e.g., Dovidio & Gartner, 2004; McConahay, 1986). As a result, outgroup attitudes often seem to be mixed (ambivalent; Fiske et al., 2002) and may be negative and/or positive depending on the context.

The complexity increases as social targets belong simultaneously to several social categories (Kulik et al., 2007). In this vein, research has mainly focused on the intersection of common highly visible demographic categories such as gender and race. For example, in a recent study, Cuadrado et al. (2021a) found that Spaniards perceived Moroccan men as less moral (e.g., trustworthy) than Spanish men, and less moral and more immoral than Moroccan women. Interestingly, no different levels of morality were ascribed to Spanish and Moroccan women.

Furthermore, concerning gender and their interaction with other factors in organizational contexts, Klein and Shtudiner (2021) found that physical attractiveness is an important factor in the judgement of ethical behavior of women but not of men. Fuegen et al. (2004) showed that parental status influenced participants’ decision to hire and promote female candidates but not male candidates. Another study (García-Ael et al., 2018) further found that professional status influenced both the perceived competence and warm for men workers but only the perceived competence for women. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that jointly consider the effects on attitudes toward ethnic minorities of both ethnicity and gender with each of these other factors in the workplace. The present research aims to explore these effects.

Contemporary theories of prejudice acknowledge that its expression is a combination of two competitive motivations: genuine prejudice and the motivation to suppress it (Crandall & Eshleman, 2003). Both aspects may be influenced by a range of factors such as the context, the social norms of prejudice expression or a person’s value system and ideological beliefs.

Egalitarian vs. Non-egalitarian Individuals

The literature has identified two general categories of values related to prejudice: individualism, which emphasizes the importance of self-reliance and the Protestant work ethic, and egalitarianism, which emphasizes the importance of all people being treated equally and fairly (e.g., Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004). Whereas individualism facilitates prejudice, theorists propose that egalitarianism is its antidote (Kite & Whitley, 2016). A genuine commitment to egalitarian goals can suppress stereotype activation because these goals are important to the self and, when chronically activated, operate implicitly. Those with chronic egalitarian goal activation (with values that suppress prejudice) do not judge or remember women or Blacks in terms of the stereotype—apparently, the stereotype is not activated for them (Moskowitz et al., 1999, 2000)—or they might even implement overcompensation strategies when evaluating stigmatized social groups.

In current societies, which are becoming increasingly diverse, acceptance, respect, and appreciation of diversity are essential to social well-being. To really understand and be able to manage the great complexity implied by diversity, different authors (see Cuadrado et al., 2021c) think that research on cultural diversity should not concentrate exclusively on prejudice, but should extend to and include analysis of tolerance. Accordingly, we will account for both racism and tolerance as proxies of (non)egalitarianism, so that individuals with high levels of tolerance or low levels of racism will be designated as egalitarian people, while those who report the reverse pattern (low levels of tolerance or high levels of racism) will be defined as non-egalitarians. We aim to analyze if and how egalitarian and non-egalitarian participants evaluate a Moroccan job candidate differently than a Spanish candidate. We expect a different pattern of judgments for egalitarian vs. non-egalitarian participants, as well as a non-simplistic but complex expression of ethnic attitudes for each case.

Models of Social Perception

Attitudinal ambivalence has been empirically confirmed by recent and robust frameworks of social perception such as the Behaviors from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes Map (BIAS Map; Cuddy et al., 2007) and its precursor, the stereotype content model (SCM; Fiske et al., 2002). According to these models, the combination of low vs. high perceived warmth and competence stereotypes determines four specific emotions (admiration, contempt, envy, and compassion) that, in turn, trigger specific behavioral tendencies toward social targets. Warmth will determine the valence of active behavioral tendencies, facilitation for warm targets and harm for cold ones, while competence will determine the valence of passive behavioral intention, facilitation for competent targets and harm for incompetent ones.

Research in the organizational context (e.g., Cuddy et al., 2011; García-Ael et al., 2018) has shown the importance of assessing warmth and competence stereotypes and their relation to discriminatory behaviors (e.g., personnel selection, hiring preferences, task assignment) toward different disadvantaged groups (e.g., women, homosexuals) in the workplace. Yet, few studies from this perspective have considered ethnic minority immigrants as targets of workplace discrimination (e.g., Agerström et al., 2012; Strinić et al., 2020), and they have mainly focused on the traditional dimensions of the stereotype content: warmth and competence.

It has recently been evidenced that the dimension of warmth encompasses two distinct subdimensions: morality (e.g., honest, sincere, trustworthy) and sociability (Leach et al., 2007). Morality has a more prominent and diagnostic role in social judgment compared to sociability and competence (Brambilla et al., 2021). The primacy of morality was also confirmed when assessing different immigrant groups (Cuadrado et al., 2016; López-Rodríguez et al., 2013) and in the workplace context as a predictor of emotional responses and helping intentions toward a newcomer (Pagliaro et al., 2013). Moreover, the primary role of morality on impression formation is mainly driven by its negative traits (for a review, see Rusconi et al., 2020). However, prior work has mainly considered positive moral content and tested whether a social group has or lacks such positive traits. Building on the evidence that suggests lacking moral qualities does not necessarily imply having a negative moral character (Rusconi et al., 2020), the present work considered stereotypes of both morality and immorality.

Beyond trying to provide a more comprehensive picture on contemporary labor discrimination of ethnic minorities considering other basic features of the target and participants’ value system, we also aim to extend the previous literature on attitudes toward ethnic minorities in organizational contexts in three ways: (a) based on the findings regarding the importance of im(morality) stereotypes in social perception, we assess four instead of two dimensions of stereotype content; (b) following the SCM and BIAS Map frameworks, we examine participants’ affective and behavioral response; and (c) we focus on positive behavioral intentions, because recent research (e.g., Cuadrado et al, 2020) has shown the importance of studying how and when we can promote positive relations and behaviors.

Current Research

Moroccans are highly stigmatized among ethnic minorities in Spain: they elicit more symbolic and realistic threats (Navas et al., 2012) and are perceived as less moral than other immigrant groups (López-Rodríguez et al., 2013). Negative mutual evaluations are a characteristic of the Spanish-Moroccan relations. Spaniards refer to socio-cultural differences (i.e., language, religion) and terrorism, whereas Moroccans emphasize being discriminated against (Amirah-Fernández, 2015). For example, according to a recent study carried out by the CCME and the IPSOS survey institute (2020), 59% of young Moroccans between 18 and 35 years of age had difficulties finding work in Spain.

Taking these data into account—and to capture the complexity of prejudice in the workplace—three preregistered experimental studies analyzed the effect of the ethnicity of a candidate (Moroccan vs. Spanish) on stereotypes, emotions, and behavioral intentions toward the candidate, accounting for possible interaction with gender and with other relevant factors: attractiveness (Study 1), parental status (Study 2), and professional status (Study 3). The target’s gender was always manipulated since there is evidence of its influence on participants’ evaluations, especially regarding Moroccan targets (see Cuadrado et al., 2021a). Moreover, we examined the moderating role of participants’ ideology/system of beliefs (tolerance and racism toward Moroccans) on the ethnicity effects.

Based on the previous literature, we expected that the expression of prejudice (a different evaluation of Moroccan candidates than Spanish ones) would be influenced by the target’s ethnicity, but in interaction with other variables (e.g., gender, attractiveness) and would especially be moderated by the observers’ system of values: egalitarians (participants with high tolerance or low racism levels) vs. non-egalitarians (participants with low tolerance or high racism levels). Studies 1 and 2 explored these hypotheses in an administrative occupation, a low prototypical context for Moroccans in Spain. Study 3 tried to confirm the hypotheses in a more typical occupation for Moroccans in Spain (Gastón-Giu et al., 2021): the hostelry. Candidates’ prototypicality was measured in Studies 2 and 3 to interpret the pattern of prejudice expression for egalitarians vs. non-egalitarians.Footnote 1

Study 1

Method

Participants

A total of 637 participants (after removing duplicates and incomplete surveys) completed the study. Following pre-registered criteria, we excluded 158 participants (2 people under 18 years old, 53 who failed the attention check questions, 101 who failed the manipulation checks, and 2 people of Moroccan ethnic origin). The final sample was composed of 479 participants (54.7% women; 96.7% born in Spain; 98.6% with Spanish nationality). Participant age ranged from 18 to 69 years (M = 34.67, SD = 13.39). Most participants (66%) did not have professional experience in the field in which the study was framed; 52% of the participants had completed university studies, 66% were active workers, and 21% were students. Participants self-located around the center of the political orientation scale (M = 2.77, SD = 0.75), ranging from 1 (extreme left) to 5 (extreme right).

Experimental Manipulation

We presented the CV of a 28-year-old person applying for an administrative job in a medium-size Spanish company. Participants were asked to imagine that they work in the same company and to evaluate the target as a possible coworker (guided by their first impression, i.e., the first thing that comes to mind). Following a 2 ethnicity (Spanish vs. Moroccan) × 2 gender (man vs. woman) × 2 attractiveness (low vs. high) between-subjects design, we built eight different CVs based on Vázquez and Lois (2020), including a picture of the candidate. The information concerning professional experience and education was identical in all cases (the targets were trained and had professional experience in the same cultural context). The gender and the ethnicity of the target were manipulated through the name (José/María García Sánchez vs. Mohamed/Fátima Hassan Alaoui) and the picture. To manipulate the level of attractiveness, we used eight standardized images (a different one for each condition) from the Chicago Face Database (CFD, Ma et al., 2015, 2021). We selected the eight images that better matched the stereotypical appearance of Spanish people (white or Latin ethnicity) and Moroccan people (black or multiracial ethnicity) based on their level of attractiveness. According to the CFD, the mean attractiveness (on a scale from 1 not at all to 7 extremely attractive) for the high-attractive conditions was 4.89, and for the low-attractive conditions was 2.49.

Measures

Participants answered the following measures thinking of the candidate as a potential coworker. Unless stated otherwise, all measures used a five-point response scale ranging from 1 (nothing) to 5 (very much) and were presented after the manipulation in the following order.

Stereotypes

We used nine items (adapted by López-Rodríguez et al., 2013 from Leach et al., 2007) to evaluate descriptive morality (honest, sincere, trustworthy; α = 0.87); sociability (likeable, friendly, warm; α = 0.85); and competence (competent, intelligent, skillful; α = 0.84); and three items (Sayans-Jiménez et al., 2017) to measure immorality (malicious, treacherous, false; α = 0.84).

Emotions

We measured the four emotions included in the SCM (Fiske et al., 2002) with eight items adapted into Spanish by Cuadrado et al. (2016): admiration and respect (admiration, r = 0.41); envy and jealousy (envy, r = 0.62); compassion and pity (compassion, r = 0.43); and contempt and discomfort (contempt, r = 0.61).

Facilitation Behavioral Tendencies

We developed eight items (Cuadrado et al., 2021b), based on the theoretical distinction established by Cuddy et al. (2007), to measure active facilitation (e.g., facilitate his/her professional training; four items: α = 0.88) and passive facilitation tendencies in the workplace (e.g., cooperate with him/her; four items: α = 0.84).

Attention Checks

We included two questions (to select a specific number) hidden among the items for the previous scales to check if participants were paying attention. Giving a wrong answer was a pre-established criterion of exclusion to guarantee the quality of the online data.

Tolerance

We used the 8-item Spanish version (Cuadrado et al., 2021c) of the scale developed by Hjerm et al. (2020) to measure tolerance toward “Moroccan immigrants” (e.g., I respect Moroccan immigrants’ opinions, even when I do not agree, α = 0.85).

Racism

We used the 11-item Spanish version (Navas, 1998) of the Modern Racism Scale (McConahay, 1986) to measure prejudice against Moroccan immigrants (e.g., Moroccan immigrants are being too demanding in their fight for equal rights, α = 0.92).

Manipulation Checks

To check if participants were sensitive to the manipulation, they had to confirm the Gender (man vs. woman) and the Ethnicity (Spaniard vs. Moroccan) of the evaluated person and to report to what extend they considered him/her attractive on a scale from 1 (not attractive) to 5 (very attractive). Participants who failed the manipulation checks were excluded following the preregistered exclusion criteria to guarantee the quality of the data.

Sociodemographic Variables

Before the manipulation checks, participants indicated their sex, age, level of education, current occupation, personal experience in the domain of the CV, nationality, birth country, and political orientation.

For exploratory reasons we also measured prescriptive stereotypes, outgroup threat, and ambivalent sexism (see Supplementary Information, SI).

Procedure

The study was designed and distributed through the Qualtrics® platform. Participants were recruited among the acquaintances of first-year students of different undergraduate degrees from the local university who received a course credit (0.25 points) for their collaboration. Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. The average time needed to fill out the questionnaires was 17 min. First, participants completed the sociodemographic questions. Next, they were presented with the CV of one of the eight experimental conditions to which they were randomly assigned. Afterwards, they responded to the main dependent variables, potential moderators, and manipulation checks. Finally, they were thanked and debriefed.

Data Analyses

To check for the effects of the manipulation on the dependent variables (stereotypes, emotions, and facilitation behavioral tendencies) we conducted three-factor MANOVAs (targets’ ethnicity × gender × attractiveness).Footnote 2 Additionally, to test whether the results were contingent on participants’ tolerance or racism, we conducted moderation analyses with Hayes’ (2018) PROCESS command (Model 1) using 5,000 bootstrap samples to estimate bias-corrected standard errors and 95% percentile confidence intervals.

A sensitivity analysis conducted a posteriori (after data collection and pre-registered exclusion criteria applied) was performed using the G ∗ Power software (Faul et al., 2007). We found that with a sample size of 479, with α = 0.05 and 1 − β (power) = 0.80, the minimum effect size that we could detect to determine the main effects of the manipulated variables via an ANOVA was ƒ = 0.128 (ηp2 = 0.016); and f2 = 0.016 (∆R2 = 0.016) to determine the moderating role of tolerance or racism on the effects of ethnicity through a multiple regression with one tested predictor for the interaction term.

Results

Manipulation Checks

Most participants correctly identified the gender (257; 87.1% for the male-candidate conditions; 294; 96.1% for the female-candidate conditions) and ethnicity of the target (248; 81.3% for the Moroccan-candidate conditions; 277; 93.6% for the Spanish-candidate conditions). Participants assigned to the high-attractiveness conditions perceived candidates as more attractive (M = 2.86, SE = 0.90) than the participants assigned to the low-attractiveness conditions (M = 2.31, SE = 0.96), t(476.193) = 6.39, p < 0.001.

Effects of Targets’ Ethnicity on Stereotypes, Emotions, and Behaviors

We found significant multivariate main effects of ethnicity on stereotypes, Wilks’s Λ = 0.971, F(4, 468) = 3.50, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.029; emotions, Wilks’s Λ = 0.931, F(4, 468) = 8.64, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.069; and facilitation tendencies, Wilks’s Λ = 0.966, F(2, 470) = 8.38, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.034. The univariate effects showed that participants attributed to Moroccan targets more sociability and competence than to Spanish targets. They also expressed more admiration and less compassion, as well as more active and passive facilitation tendencies at work, toward Moroccan than toward Spanish candidates (see SI for detailed statistical information of the univariate effects).

Effects of Targets’ Attractiveness on Stereotypes, Emotions, and Behaviors

We found significant multivariate main effects of target’s attractiveness on stereotypes, Wilks’s Λ = 0.962, F(4, 468) = 4.66, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.038; emotions, Wilks’s Λ = 0.978, F(4, 468) = 2.58, p = 0.037, ηp2 = 0.022; and facilitation tendencies, Wilks’s Λ = 0.987, F(2, 470) = 3.09 p = 0.047, ηp2 = 0.013. The univariate effects showed that the participants attributed less sociability, felt more compassion, and reported more active facilitation tendencies at work toward low than toward high-attractive candidates.

Finally, no significant multivariate main effects of gender or multivariate three-way or two-way interaction effects between the variables were found, F < 3.61, p > 0.058 (see SI for detailed statistical information of the univariate effects).

Effects of Target’s Ethnicity on Stereotypes, Emotions, and Behaviors Moderated by Tolerance and Racism

As preregistered, we explored the possible interaction of target’s ethnicity (Moroccan vs. Spanish candidates) with perceivers’ system of values (i.e., level of tolerance and racism) including targets’ gender and attractiveness as covariates.

The results showed that the effect of ethnicity on stereotypes was moderated by (a) participants’ tolerance for sociability, B = 0.22, 95% CI [0.02, 0.41], ∆R2 = 0.012; competence, B = 0.30, 95% CI [0.13, 0.47], ∆R2 = 0.030; morality, B = 0.38, 95% CI [0.18, 0.57], ∆R2 = 0.037; and immorality, B = − 0.37, 95% CI [− 0.57, − 0.16], ∆R2 = 0.038. Ethnicity also interacted with (b) participants’ racism on competence, B = − 0.15, 95% CI [− 0.30, − 0.01], ∆R2 = 0.012; morality, B = − 0.28, 95% CI [− 0.44, − 0.13], p < 0.001, ∆R2 = 0.030; and immorality, B = 0.29, 95% CI [0.13, 0.45], ∆R2 = 0.034. Specifically, participants with high levels of tolerance or low levels of racism (egalitarian participants) attributed more competence and morality and less immorality to Moroccan targets than to Spanish targets. Moreover, participants with high levels of tolerance considered Moroccan candidates to be more sociable than Spanish ones. In contrast, non-egalitarian participants (low tolerance or high racism) perceived Moroccan candidates as more immoral than Spanish targets. Also, participants with low levels of tolerance perceived Moroccan candidates as less moral than Spanish ones (see Table 1a).

The effect of ethnicity on admiration and contempt also interacted with (a) tolerance, B = 0.31, 95% CI [0.11, 0.52], ∆R2 = 0.025; B = − 0.28, 95% CI [− 0.50, − 0.06], ∆R2 = 0.026, respectively; and (b) racism, B = − 0.16, 95% CI [− 0.31, − 0.0001], ∆R2 = 0.009; B = 0.22, 95% CI [0.07, 0.38], ∆R2 = 0.023, respectively. Concretely, participants with high levels of tolerance or low levels of racism (egalitarian participants) reported more admiration and less contempt toward Moroccan than toward Spanish targets. No differences between the evaluations of Moroccan versus Spanish targets were found for non-egalitarian participants (low tolerance or high racism). See Table 2a.

Finally, the effect of ethnicity on facilitation tendencies was also contingent on (a) tolerance for active facilitation, B = 0.29, 95% CI [0.08, 0.50], ∆R2 = 0.019, and passive facilitation, B = 0.33, 95% CI [0.15, 0.53], ∆R2 = 0.024; and (b) racism for passive facilitation, B = − 0.17, 95% CI [− 0.33, − 0.01], ∆R2 = 0.009. In particular, participants with a high level of tolerance or low level of racism manifested more passive facilitation toward Moroccan than toward Spanish targets. The same pattern was found for active facilitation, but only for highly tolerant participants. No differences were found for participants with low tolerance or high racism (see Table 2a).

Discussion

In this study, we explored the conjoint effect of ethnicity, gender, and attractiveness on stereotypes, emotions, and facilitation behavioral intentions in the workplace. Contrasting with previous studies, we did not find main effects of gender (e.g., García-Ael et al., 2018), or consistent interactive effects between gender and physical attractiveness (e.g., Klein & Shtudiner, 2021), or gender and ethnicity (e.g., Cuadrado et al., 2021a) on the studied variables.

The most consistent and intriguing results occurred depending on the target’s ethnicity. Contrary to what we expected based on the predictions of the SCM (Fiske et al., 2002) and BIAS Map (Cuddy et al., 2007), participants attributed more sociability and competence, and they expressed more admiration and facilitation behavioral tendencies (both active and passive) and less compassion toward Moroccan than toward Spanish targets. Thus, the results showed an unexpected pattern of positive outgroup bias. We found evidence that this bias was manifested only by egalitarian participants (high in tolerance or low in racism), and that the moderating effect of tolerance was more consistent than that of racism. These findings show the relevance of going beyond prejudice and including tolerance when studying intergroup relations (Cuadrado et al., 2021c).

Further, our results revealed the prominent role of (im)morality in social judgments (Brambilla et al., 2021). Thus, only for this one stereotype dimension did a consistent but reversed pattern emerge for non-egalitarian participants as well: Moroccans compared to Spaniards were perceived as more immoral by participants low in tolerance or high in racism, and as less moral by participants with low tolerance.

We wondered if candidates’ prototypicality might explain these results, so, in Study 2 we explore the perceived typicality of candidates and plan to confirm the role of tolerance and racism as moderators of the effect of ethnicity.

Study 2

In Study 2, we further extend the findings of Study 1 by exploring the conjoint effect of ethnicity, gender, and parental status (Fuegen et al., 2004; Smith, 2002) on stereotypes, emotions, and behavioral tendencies in the workplace. Moreover, given the exploratory nature of Study 1, we also aim to confirm the moderating role of tolerance and racism on the ethnicity effect. The low representativeness of Moroccans working in administration might help to understand the previous findings. Therefore, in this study we explore the perceived typicality of Moroccan and Spanish candidates, and if this perception varies depending on participant’s levels of tolerance and racism.

Method

Participants

A total of 704 participants (after removing duplicates and incomplete surveys) completed the study. Following pre-registered criteria, we excluded 257 participants (2 people under 18 years old, 2 participants of Moroccan origin, 50 who failed the attention check, and 203 who failed the manipulation checks; see SI). The final sample consisted of 447 participants (63.1% women; 96.2% born in Spain; 98.7% with Spanish nationality). Participant age ranged from 18 to 77 years (M = 29.80, SD = 12.39). Most participants (75.6%) did not have professional experience in the field in which the study was framed, were active workers (46.3%) or students (47%), and had completed university studies (60.4%). Participants self-located around the center of the political orientation scale (M = 2.57, SD = 0.76), ranging from 1 (extreme left) to 5 (extreme right). An a posteriori sensitivity analysis using G ∗ Power (Faul et al., 2007) showed that with this sample size (N = 447), with α = 0.05 and 1 − β = 0.80, the minimum effect size that we could detect to determine the main effects of the manipulated variables via an ANOVA was ƒ = 0.133 (ηp2 = 0.017); and to determine the moderating role of tolerance or racism on the effects of ethnicity through a multiple regression with one tested predictor for the interaction term was f2 = 0.018 (∆R2 = 0.018).

Experimental Manipulation

Following a 2 ethnicity (Spanish vs. Moroccan) × 2 gender (man vs. woman) × 2 parental status (parent vs. non-parent) between-subjects design, we built eight different CVs, manipulating ethnicity and gender as in Study 1 and keeping the level of attractiveness consistent through the experimental conditions (we selected the pictures of high-attractive candidates used in Study 1). To manipulate parental status, we specified before presenting the CV that the candidate had just become a father/mother (parent condition).

Measures

Using the same measures described in Study 1, we evaluated stereotypes (sociability: α = 0.81; competence: α = 0.80; morality: α = 0.81; immorality: α = 0.76); emotions (admiration: r = 0.40; envy: r = 0.66; compassion: r = 0.42; contempt: r = 0.52); facilitation behavioral tendencies (active α = 0.88; passive α = 0.83); tolerance (α = 0.86); and racism (α = 0.91).

Additionally, we measured perceived typicality based on Brown et al. (2007). Participants reported on a 5-point response scale ranging from 1 (nothing) to 5 (very much) to what extent they perceived that the target resembled the members of his/her ethnic group in general (Spaniards or Moroccans). Attention and manipulation checks and sociodemographic variables were measured as in Study 1. We included the same additional measures (except prescriptive stereotypes) for exploratory purposes as in Study 1 (see SI).

Procedure

The same procedure was followed as in Study 1, but here we asked participants’ age and gender before the manipulation to identify the duplicate cases more easily. The average time needed to fill out the questionnaires was 18 min.

Results

Effects of Targets’ Ethnicity on Stereotypes, Emotions, and Behaviors

We found significant multivariate main effects of ethnicity on stereotypes, Wilks’s Λ = 0.961, F(4, 436) = 4.37, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.039; emotions, Wilks’s Λ = 0.942, F(4, 436) = 6.67, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.058; and facilitation tendencies, Wilks’s Λ = 0.967, F(2, 438) = 7.37, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.033.The univariate effects replicated the unexpected positive outgroup bias toward Moroccan candidates: participants considered Moroccan candidates more moral, sociable, and competent than Spanish ones. They also reported more admiration and less contempt, as well as more active and passive facilitation toward Moroccan than toward Spanish targets (see SI for detailed statistical information of these univariate effects).

Effects of Targets’ Gender on Stereotypes, Emotions, and Behaviors

We found significant multivariate main effects of target’s gender on stereotypes, Wilks’s Λ = 0.971, F(4, 436) = 3.29, p = 0.011, ηp2 = 0.029; emotions, Wilks’s Λ = 0.939, F(4, 436) = 7.13, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.061; and facilitation tendencies, Wilks’s Λ = 0.964, F(2, 438) = 8.24, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.036. Unlikely Study 1, participants rated more positively women than men in terms of sociability, competence, morality, immorality, admiration, contempt, and active and passive facilitation tendencies (see SI for detailed statistical information of these univariate effects).

Effects of Targets’ Parental Status on Stereotypes, Emotions, and Behaviors

We found significant multivariate main effects of parental status only on facilitation tendencies, Wilks’s Λ = 0.984, F(2, 438) = 3.51 p = 0.031, ηp2 = 0.016. Univariate effects showed that participants expressed more active and passive facilitation behavioral tendencies toward childless that toward parent candidates (see SI for detailed statistical information of this univariate effect).

Interactive Effects of Targets’ Ethnicity, Gender and Parental Status on Stereotypes, Emotions, and Behaviors

We did not find a clear and consistent pattern of results regarding interaction effects of the manipulated variables on stereotypes, emotions, and behaviors (see SI for detailed information on these results).

Effects of Target’s Ethnicity on Stereotypes, Emotions, and Behaviors Moderated by Tolerance and Racism

The same moderation analyses as in Study 1 revealed that the effect of ethnicity on stereotypes was moderated by (a) tolerance on sociability, B = 0.19, 95% CI [0.03, 0.35], ∆R2 = 0.011; and morality, B = 0.21, 95% CI [0.04, 0.38], ∆R2 = 0.014; and (b) racism on sociability, B = − 0.28, 95% CI [− 0.43, − 0.13], ∆R2 = 0.032; competence, B = − 0.14, 95% CI [− 0.27, − 0.004], ∆R2 = 0.010; and morality, B = − 0.25, 95% CI [− 0.40, − 0.11], ∆R2 = 0.029. Specifically, participants with high levels of tolerance attributed more sociability and morality, and less immorality to Moroccan targets than to Spaniards. Likewise, participants with low levels of racism attributed more sociability, competence, and morality to Moroccan targets compared to Spaniards. No differences were found for participants with low tolerance or high racism (see Table 1b).

The effect of ethnicity on emotions was also contingent on (a) tolerance for contempt, B = − 0.21, 95% CI [− 0.36, − 0.06], ∆R2 = 0.019 and (b) racism for both admiration, B = − 0.26, 95% CI [− 0.43, − 0.09], ∆R2 = 0.021 and contempt, B = 0.17, 95% CI [0.06, 0.29], ∆R2 = 0.018. Concretely, participants with high levels of tolerance or low levels of racism reported less contempt toward Moroccan than toward Spanish targets. Similarly, participants with low levels of racism reported more admiration toward Moroccan than toward Spanish candidates. No differences were found for participants with low tolerance or high racism (see Table 2b).

Finally, we also found that the effect of ethnicity on facilitation tendencies was moderated by (a) tolerance on active facilitation, B = 0.30, 95% CI [0.11, 0.50], ∆R2 = 0.022, and (b) racism on active facilitation, B = − 0.36, 95% CI [− 0.52, − 0.21], ∆R2 = 0.045, and passive facilitation, B = − 0.29, 95% CI [− 0.46, − 0.12], ∆R2 = 0.029. In particular, participants with high levels of tolerance or low levels of racism reported more active facilitation toward Moroccan than toward Spaniards. Participants with low levels of racism also manifested more passive facilitation toward Moroccan than toward Spanish targets. No differences were found for participants with low tolerance or high racism (see Table 2b).

Effects of Target’s Ethnicity on Perceived Typicality and Interaction with Tolerance and Racism

The ANCOVA (with gender and parental status as covariates) conducted to test the effect of ethnicity on perceived typicality was significant, F(1, 443) = 86.46, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.163. Participants perceived the Moroccan target as less prototypical of their own group (i.e., Moroccans; M = 2.87, SE = 0.06), than the Spanish target (i.e., Spaniards; M = 3.65, SE = 0.06). No other significant main or interaction effects were found.

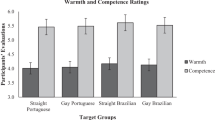

Moderation analysis revealed an interaction effect of ethnicity with (a) tolerance, B = 0.27, 95% CI [0.02, 0.52], ∆R2 = 0.011; and (b) racism, B = − 0.32, 95% CI [− 0.51, − 0.13], ∆R2 = 0.022, on target’s perceived typicality. Although participants perceived Moroccan targets as less prototypical of Moroccans than Spanish targets of Spaniards regardless of their tolerance or racism levels (see Fig. 1), non-egalitarian participants (low in tolerance, B = − 0.98, 95% CI [− 1.24, − 0.72], ∆R2 = 0.011; or high in racism, B = − 1.05, 95% CI [− 1.30, − 0.81], ∆R2 = 0.022) perceived greater differences in typicality between Moroccan and Spanish candidates than egalitarian participants (high in tolerance: B = − 0.56, 95% CI [− 0.80, − 0.31], p < 0.001; and low in racism: B = − 0.47, 95% CI [− 0.70, − 0.24], p < 0.001).

Discussion

Study 2 revealed that participants perceived Moroccan candidates as less typical of Moroccans than Spanish candidates of Spaniards, and this effect was stronger for non-egalitarian participants. In accordance with modern theories of prejudice (e.g., aversive prejudice: Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004; modern racism: McConahay, 1986), this might explain why we did not find a negative outgroup bias in non-egalitarian participants (this issue will be further addressed in the General Discussion). The results also confirmed the role of tolerance and racism as moderators of the positive outgroup bias toward Moroccan candidates, but with small differences compared to Study 1. In Study 2, unlike Study 1, the moderating role of racism was more consistent across measures than the role of tolerance, highlighting the relevance of measuring both aspects.

Our findings also showed that female candidates were more positively assessed than male candidates, which may have important implications on the differential evaluation of women and men at work. However, contrary to previous research, the gender of the target did not consistently influence participants’ evaluations regarding ethnicity (Cuadrado et al., 2021a) or parental status (Fuegen et al, 2004) –which did not perform any role on the studied variables. The different and specific framing of the studies may explain these findings, since we focused here on interpersonal evaluations of single candidates at work.

Study 3

The main goal of this study was to replicate the role of tolerance and racism as moderators of the effect of ethnicity on stereotypes, emotions, and behavioral tendencies in the workplace found in Studies 1 and 2, but in a different occupational setting. The previous studies were set in the context of administration, and candidates were described as having a specialized background for the administrative job for which they applied. However, in this context, Moroccan candidates were perceived as less typical than Spanish workers (Study 2). This frame may have activated an exemplar instead of the schema of ‘Moroccans’, leading participants to perceive Moroccan candidates as highly counter-stereotypical of Moroccans in Spain. As occupational distribution of Moroccan men and women in Spain is lower in administrative than hostelry occupations (Gastón-Giu et al., 2021), to rule out the effect of context as a possible explanation of our findings, we framed Study 3 in the hostelry domain. We thus test whether the moderated effect of ethnicity by the ideological variables found in Studies 1 and 2 would be replicated even in a different sector. Additionally, we manipulate the professional status (high vs. low) to explore the interaction between ethnicity and professional status on targets’ typicality.

Method

Participants

A total of 730 participants (after removing duplicates and incomplete surveys) completed the study. Following pre-registered criteria, we excluded 149 participants (2 people under 18 years old, 7 participants of Moroccan origin, 46 who failed the attention check question, and 94 who failed the manipulation checks; see SI). The final sample consisted of 581 participants (59.7% women; 96% born in Spain; 98.3% with Spanish nationality). Participant age ranged from 18 to 69 years (M = 33.56, SD = 13.76). Most participants (69.9%) did not have professional experience in the field in which the study was framed, were active workers (55.2%) or students (33.7%), and 54% of participants had completed university studies. Participants self-located around the center of the political orientation scale (M = 2.61, SD = 0.77), ranging from 1 (extreme left) to 5 (extreme right). An a posteriori sensitivity analysis using G ∗ Power (Faul et al., 2007) showed that with this sample size (N = 581), with α = 0.05 and 1 − β = 0.80, the minimum effect size that we can detect to determine the main effects of the manipulated variables via an ANOVA was ƒ = 0.116 (ηp2 = 0.013); and f2 = 0.013 (∆R2 = 0.013) to determine the moderating role of tolerance or racism on the effects of ethnicity through a multiple regression with one tested predictor for the interaction term.

Experimental Manipulation

Following a 2 ethnicity (Spanish vs. Moroccan) × 2 gender (man vs. woman) × 2 professional status (high vs. low) between-subjects design, we built eight different CVs, manipulating ethnicity and gender as in the Studies 1 and 2, and using the pictures of high-attractive candidates as in Study 2. The candidates applied for a job in a restaurant. We manipulated the professional status through the information on the CV concerning professional experience and education. For high-status conditions, the candidate had a high level of education and previous experience in high-status jobs (head cook), whereas for low-status conditions, the candidate had a low level of education and previous experience in low-status jobs (dishwasher).

Measures and Procedure

The procedure was the same as in Study 2. The average time needed to fill out the questionnaires was 18.2 min. Using the same measures described in Study 1, we evaluated stereotypes (sociability: α = 0.82; competence: α = 0.79; morality: α = 0.87; immorality: α = 0.81); emotions (admiration: r = 0.44; envy: r = 0.63; compassion: r = 0.44; contempt: r = 0.43); facilitation behavioral tendencies (active: α = 0.87; passive: α = 0.80); tolerance (α = 0.85); and racism (α = 0.92). As in Study 2, we also included an item to assess perceived typicality. Attention and manipulation checks, and sociodemographic variables were measured as in Study 2. We included the same additional measures for exploratory purposes as in Study 2 (see SI).

Results

Effects of Targets’ Ethnicity on Stereotypes, Emotions, And Behaviors

We found significant multivariate effects of ethnicity on stereotypes, Wilks’s Λ = 0.972, F(4, 570) = 4.06, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.028; emotions, Wilks’s Λ = 0.974, F(4, 570) = 3.86, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.026; and facilitation tendencies, Wilks’s Λ = 0.976, F(2, 572) = 6.98, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.024. The univariate effects replicated once again the unexpected positive outgroup bias toward Moroccan candidates. Participants attributed more competence, felt more admiration, and expressed more active and passive facilitation intentions toward Moroccan targets than toward Spanish targets (see SI for statistical information of these univariate effects).

Effects of Targets’ Gender on Stereotypes, Emotions, and Behaviors

Regarding target’s gender, we found significant multivariate effects only on stereotypes, Wilks’s Λ = 0.974, F(4, 570) = 3.77, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.026. The univariate effects showed that participants attributed to female targets more sociability, competence, and morality than to male targets (see SI for statistical information of these univariate effects).

Effects of Targets’ Professional Status on Stereotypes, Emotions, and Behaviors

We found significant multivariate effects of professional status on stereotypes, Wilks’s Λ = 0.840, F(4, 570) = 27.10, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.160; emotions, Wilks’s Λ = 0.855, F(4, 570) = 24.18, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.145; and facilitation tendencies, Wilks’s Λ = 0.968, F(2, 572) = 9.50 p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.032. High-status targets, compared to low-status targets, were evaluated as more competent, elicited more admiration, contempt, envy and less compassion, and triggered more active and passive facilitation behavioral tendencies.

Finally, no significant multivariate three-way or two-way interaction effects between the variables were found (see SI for statistical information of the univariate effects).

Effects of Target’s Ethnicity on Stereotypes, Emotions, and Behaviors Moderated by Tolerance and Racism

The moderation analysis revealed an interaction effect of ethnicity with (a) tolerance on morality, B = 0.31, 95% CI [0.16, 0.46], ∆R2 = 0.027; and immorality, B = − 0.32, 95% CI [− 0.48, − 0.16], ∆R2 = 0.033; and (b) racism on sociability, B = − 0.20, 95% CI [− 0.33, − 0.06], ∆R2 = 0.017; competence, B = − 0.15, 95% CI [− 0.27, − 0.03], ∆R2 = 0.009; morality, B = − 0.29, 95% CI [− 0.42, − 0.17], ∆R2 = 0.036; and immorality, B = 0.24, 95% CI [0.12, 0.37], ∆R2 = 0.029. Concretely, participants with high levels of tolerance attributed more morality and less immorality to Moroccans than to Spaniards. Likewise, participants with low levels of racism attributed more sociability, competence, morality, and less immorality to Moroccans than to Spaniards. Finally, participants with low tolerance attributed more immorality to Moroccan candidates than to Spanish targets, and participants with high levels of racism attribute less sociability, morality, and more immorality to Moroccan than to Spanish targets (see Table 1c).

The moderation analysis also revealed that the effect of ethnicity was contingent on (a) tolerance for admiration, B = 0.41, 95% CI [0.22, 0.59], ∆R2 = 0.036; and contempt, B = − 0.18, 95% CI [− 0.32, − 0.04], ∆R2 = 0.019; and (b) racism for both admiration, B = − 0.28, 95% CI [− 0.42, − 0.13], ∆R2 = 0.025; and contempt, B = 0.12, 95% CI [0.02, 0.23], ∆R2 = 0.013. Specifically, egalitarian participants (high tolerance or low racism) reported more admiration and less contempt toward Moroccan than toward Spaniard targets. No differences in emotions were found for non-egalitarian participants (see Table 2c).

Once again, we found an interaction of ethnicity with (a) tolerance on active facilitation, B = 0.43, 95% CI [0.25, 0.61], ∆R2 = 0.043; and passive facilitation, B = 0.40, 95% CI [0.23, 0.58], ∆R2 = 0.038; and (b) racism on active facilitation, B = − 0.24, 95% CI [− 0.38, − 0.09], ∆R2 = 0.020; and passive facilitation, B = − 0.29, 95% CI [− 0.43, − 0.14], ∆R2 = 0.028. In particular, egalitarian participants (high levels of tolerance or low levels of racism) reported more facilitation tendencies (active and passive) toward Moroccan targets than toward Spaniards. No differences were found for non-egalitarian participants (see Table 2c).

Effects of Ethnicity and Professional Status on Perceived Typicality

The two-factor ANCOVA (with gender as covariate) conducted to test the effect of ethnicity and professional status on perceived typicality was significant for ethnicity, F(1, 576) = 58.01, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.091; and professional status, F(1, 576) = 9.41, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.016. Participants perceived Moroccan targets as less prototypical of Moroccans (M = 2.95, SE = 0.06) than Spanish targets of Spaniards (M = 3.58, SE = 0.06). Participants also perceived high-status candidates as less prototypical of their own group (both Moroccans and Spaniards; M = 3.14, SE = 0.06) than low-status candidates (M = 3.39, SE = 0.06). No interaction effects were found.

Unlike Study 2, there were no interaction effects of ethnicity with tolerance or racism on perceived typicality.

Discussion

Overall, Study 3 confirmed a pattern of results similar to Studies 1 and 2 in a different occupational setting (hostelry), which was selected to increase the perceived typicality of Moroccan targets (because the occupational distribution of Moroccan workers in Spain is greater in hostelry than in administration; Gaston-Guiu et al., 2021). However, participants again perceived Moroccan targets as less prototypical of Moroccans than Spanish targets of Spaniards, and participant’s levels of tolerance or racism did not moderate this effect.

We confirmed once again the positive outgroup bias toward Moroccan candidates among egalitarian participants, but we also found that non-egalitarian participants showed the traditional negative outgroup bias (or positive ingroup bias; Tajfel & Turner, 1979) for some stereotypical dimensions, mainly im(morality).

The low perceived typicality of Moroccan candidates not only might explain why egalitarian participants showed a positive outgroup bias toward Moroccan candidates, but also it might allow us to understand why non-egalitarian participants did not differentiate between Spanish candidates and low-typical Moroccans in competence or sociability, but still perceived differences along the core dimensions of social perception: morality and immorality.

Moreover, in line with the results of Study 2, there was a positive bias toward female targets. Additionally, candidates to high-status positions were in general better evaluated than their low-status counterparts, confirming previous results (e.g., García-Ael et al., 2018). However, like in Studies 1 and 2, the interactions between factors were scarce and inconsistent.

Pooled Analyses of Studies 1, 2, and 3

Across three studies, there was evidence that the effect of candidate ethnicity on stereotypes, emotions, and behavioral tendencies was moderated by participants’ level of tolerance or racism. However, some effects were not consistent across studies. We pooled the data following an integrative data analysis approach (Curran & Hussong, 2009) to provide insight into the robustness of these effects with more statistical power, sample heterogeneity, and controlling by different occupations (administration in Studies 1 and 2; hostelry in Study 3). According to previous findings, we considered that the effects of candidate ethnicity might be conditioned by participants’ ideology/value system toward Moroccan immigrants.

Method

Participants

The total sample included 1,507 participants (n1 = 479; n2 = 447; n3 = 581). Results of an a posteriori sensitivity analysis (Faul et al., 2007) showed that with α = 0.05 and 1 − β = 0.80, for a sample size of 1507 participants the minimum effect size that we could detect to determine the moderating role of tolerance or racism on the effects of ethnicity through a multiple regression with one tested predictor for the interaction term was f2 = 0.005 (∆R2 = 0.005).

Results

We conducted the same moderation analyses as in previous studies. We created two dummy variables to control for possible effects of the specific study, which were introduced as covariates in the analyses.

We found an interaction effect of ethnicity with (a) tolerance on sociability, B = 0.18, 95% CI [0.08, 0.28], ∆R2 = 0.009; competence, B = 0.17, 95% CI [0.08, 0.26], ∆R2 = 0.009; morality, B = 0.30, 95% CI [0.20, 0.40], ∆R2 = 0.026; and immorality, B = − 0.29, 95% CI [− 0.39, − 0.18], ∆R2 = 0.027). We also found an interaction effect of ethnicity with (b) racism on sociability, B = − 0.18, 95% CI [− 0.26, − 0.09], ∆R2 = 0.012; competence, B = − 0.16, 95% CI [− 0.24, − 0.09], ∆R2 = 0.012; morality, B = − 0.28, 95% CI [− 0.36, − 0.20], ∆R2 = 0.033; and immorality, B = 0.21, 95% CI [0.12, 0.29], ∆R2 = 0.020. Egalitarian participants attributed more sociability, competence, morality, and less immorality to Moroccan than to Spanish candidates. However, non-egalitarian participants did not differentiate in competence or sociability between Moroccan and Spanish candidates, but they attributed less morality and more immorality to Moroccans compared to Spaniards (see Table 1d and Fig. 2).

Concerning emotions, we found an interaction effect of ethnicity with (a) tolerance on admiration, B = 0.31, 95% CI [0.20, 0.42], ∆R2 = 0.022; and contempt, B = − 0.21, 95% CI [− 0.31, − 0.11], ∆R2 = 0.019; and (b) racism on both admiration, B = − 0.24, 95% CI [− 0.33, − 0.15], ∆R2 = 0.018; and contempt, B = 0.17, 95% CI [0.09, 0.24], ∆R2 = 0.017. Participants with high levels of tolerance or low levels of racism reported more admiration and less contempt toward Moroccan targets than toward Spaniards. No differences were found for non-egalitarian participants (see Table 2d and Fig. 3).

Finally, regarding facilitation tendencies, we found an interaction effect of ethnicity with (a) tolerance on active facilitation, B = 0.34, 95% CI [0.23, 0.46], ∆R2 = 0.028; and passive facilitation, B = 0.30, 95% CI [0.20, 0.41], ∆R2 = 0.022; and (b) racism on active facilitation, B = − 0.24, 95% CI [− 0.33, − 0.15], ∆R2 = 0.020; and passive facilitation, B = − 0.25, 95% CI [− 0.34, − 0.16], ∆R2 = 0.020. Participants with high levels of tolerance or low levels of racism reported more facilitation toward Moroccan targets than toward Spaniards. No differences were found for non-egalitarian participants (see Table 2d and Fig. 3).

Discussion

The pooled data analyses revealed in a robust way that egalitarian participants (high tolerance or low racism) attributed more sociability, competence, morality, and less immorality to Moroccan than to Spanish targets. Likewise, these participants experienced more admiration and less contempt and expressed more facilitation (active and passive) tendencies at work toward Moroccans than toward Spaniards. Thus, the results confirmed a very consistent positive outgroup bias for egalitarian participants. The results also revealed the primacy of im(morality) in social perception (Brambilla et al., 2021), because the opposite pattern of results for non-egalitarian participants was found only for this dimension. That is, participants with low tolerance or high racism scores considered Moroccans as less moral and more immoral than Spanish targets.

General Discussion

The present work extends previous research on prejudice in the workplace by analyzing the interactive effect of ethnicity and other relevant characteristics (e.g., gender, attractiveness) of a job applicant, as well as possible ideological moderators (tolerance or racism), on participants’ judgments about the candidate: stereotypes (competence, sociability, morality, and immorality); emotions (admiration, contempt, compassion, and envy); and active and passive facilitation tendencies at work.

Across three studies, we found a consistent and unexpected pattern of results: a positive outgroup bias toward Moroccan candidates. Although we examined the intersection of ethnicity with other characteristics such as gender or attractiveness, the category that most consistently influenced participants’ evaluation (stereotypes, emotions, and behavioral intentions) and the most relevant for this work was ethnicity. Ethnicity salience over other social categories on intergroup prejudice might be related with its stronger association with threat and conflict (Levin et al., 2002). Relatedly, Grygoryan (2019) has found that the conflict and symbolic threat associated with a social category were more predictive of which social category dimension produces more bias: membership to socio-cultural groups (e.g., religion, ethnicity) produced more intergroup bias than membership to groups defined by socioeconomic dimensions (e.g., income, occupation). Thus, a possible explanation of ethnicity salience is the fact that Moroccan immigrants are perceived as a low-status threatening immigrant group (López-Rodriguez et al., 2013; Navas et al., 2012). Furthermore, the salience of ethnicity is dependent on context (e.g., Kinzler et al., 2010). Perhaps the framing we used made ethnicity more salient, because Moroccan candidates are perceived as not very prototypical, and the lack of fit with the stereotype of Moroccans may have led to more individualized and more positive evaluations.

However, the effect of ethnicity was always modulated by the observers’ value system, such that the positive outgroup bias appeared only among egalitarian participants. Thus, current research allows us to distinguish a different pattern of psychosocial functioning between egalitarian and non-egalitarian people, regardless of the occupational setting (administrative in Studies 1 and 2; hostelry in Study 3). Egalitarianism has been proposed as an antidote to prejudice (Kite & Whitley, 2016). In fact, previous research has shown that, for individuals with chronic egalitarian goals (vs. without chronic egalitarian goals), the cultural stereotype for the group African Americans was not activated when they were exposed to a picture of an African American (Moskowitz et al., 2000). Our findings might be interpreted as evidence in the same line in some European contexts. However, the fact that egalitarian participants not only did not show an ingroup bias toward Spanish targets but showed an outgroup bias toward Moroccan targets may reflect the implementation of overcompensation strategies in evaluating stigmatized social groups. It might be also possible that the positive evaluations of Moroccans (vs. Spaniards) may actually reflect a paternalistic attitude that still hides residual and pervasive ethnic prejudice (Fiske et al., 2002). Future research should further explore this possible interpretation.

Surprisingly, non-egalitarians (low tolerance and high racism) did not differentiate between Moroccans and Spaniards in most stereotypes, emotions, or tendencies, but still perceived Moroccans as less moral and more immoral than Spaniards. Theories of contemporary prejudice argue that even people who have not yet fully accepted the norm of equality are motivated to act in nonprejudiced ways, which makes them express prejudice only when it can be justified (Kite & Whitely, 2016). The fact that an ingroup bias was found for morality and immorality judgments even when Moroccan candidates were perceived as less prototypical supported the primacy of (im)morality in social perception (Brambilla et al., 2021). This suggests that evaluating the perception of an ethnic outgroup in terms of (im)morality might be crucial for unmasking prejudiced people. As a consequence, (im)morality might be harder to modify among non-egalitarian people through prejudice reduction strategies, such as the use of counter-stereotypical exemplars. These stereotypical components should therefore be altered through alternative methods. Although the exposure to non-prototypical Moroccans could have caused non-egalitarians to override their overall ingroup bias, the distrust toward Moroccans persisted. This pervasive residual of prejudice can have perverse implications for Moroccans and can perpetuate ethnic discrimination among non-egalitarians individuals.

The low typicality of Moroccan candidates might help to explain these findings for both egalitarians and non-egalitarians. The manipulation depicted Moroccan candidates positively (e.g., with education and professional experience in accordance with the requirements of the job position) and even assimilating postures (e.g., women not wearing the hijab). This might have activated counter-stereotypes examples, which may have led both egalitarian and non-egalitarian participants to regulate the expression of prejudice. In the case of egalitarians, an attributional principle of augmentation might have been activated. Egalitarians might have formed a better impression of Moroccan candidates because they are aware of other factors, such as their ethnicity, that could have prevented or inhibited success or having academic training and professional experience in such fields. The value system of non-egalitarian participants probably centers on individualism, which emphasizes hard work and personal responsibility on the way to success (Protestant work ethic). According to these values, it would not be justified or politically correct to express prejudice (in terms of stereotypes, emotions, and behaviors) toward the Moroccan candidates (interpersonal framing) described in our materials (whose CVs show that they have training and personal experience in the domain of the job for which they are applying).

Future work should further explore the mechanisms of expression and suppression that egalitarian and non-egalitarian participants might be using in this context, as well as using an alternative framing to test whether the results are replicated in a context where Moroccan candidates are perceived as more prototypical (e.g., agriculture in Spain) or with very low qualified candidates. This may allow the ingroup bias to emerge among non-egalitarian participants, as well as testing whether the positive outgroup bias among egalitarian participants remains. Alternatively, we could test if presenting high vs. low prototypical Moroccan workers or interpersonal vs. intergroup framings would modulate these findings.

Limitations

Our work presents some limitations. First, the use of a convenience sample within the acquaintances of undergraduate students of Psychology limits the generalizability of the findings (see Bracht & Glass, 1968; Mullinix et al., 2015). Second, given the sensitive nature of the studied measures, social desirability should have been contemplated, especially when considering egalitarians participants’ views. However, evidence suggests that the online self-administrated data collecting mode, as well as the reassurance of participants’ anonymity should contribute to diminishing participants’ tendency to respond in a sociably desirable way (see Krumpal, 2013). Additionally, people’s motivation to express or suppress prejudice has been found to be influenced by the normative context (e.g., Crandall & Eshleman, 2003; Froscher et al., 2015). The Spanish context is nowadays characterized by a liberalized hate speech against immigration (see Arcila-Calderón et al., 2020), as exemplified by the rise of political parties with xenophobic views (the far-right party was the third most voted political force in the last Spanish general elections; see Rama et al., 2021). Thus, normative climate encouraging the expression of prejudice might have also strengthened people’s motivation to express prejudice (Froscher et al., 2015). However, future studies should analyze more deeply the role of social desirability linked to the social norms in the expression or suppression of prejudice.

Practical Implications

This research may have implications in the development of prejudice reduction strategies. Whether or not people have different value systems that make them perceive reality differently, it seems quite reasonable to think that not all prejudice reduction strategies will work in the same way for everyone. The fact that non-egalitarian participants only showed ingroup bias when they evaluated the target in terms of morality and immorality may reveal that the expression of prejudice in other stereotypical dimensions (such as sociability and competence), as well as in emotions and behavioral tendencies, are more easily suppressed (or more difficult to justify). The activation of counter-stereotypical exemplars may be a potential explanation for the lack of ingroup bias in most dimensions evaluated, but the fact that non-egalitarian participants still showed ingroup bias when they evaluated the (im)morality of the candidates suggests that extra effort is needed to modify the expression of prejudice concerning (im)morality. Future research should address the need to design interventions focused on specific aspects of prejudice, as well as considering the best way to adapt interventions to the target population (taking into account how individual value systems may modulate their success).

Main Contribution and Conclusions

The current work highlights the importance of people’s value system in evaluating ethnic minority candidates in the workplace. Egalitarian participants (high tolerance/low racism) not only did not show an ingroup bias toward Spanish targets but showed a positive outgroup bias toward Moroccan job applicants in terms of stereotypes, emotions, and behavioral facilitation tendencies, which is exceptional considering one of the most basic intergroup phenomena: positive ingroup bias (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). By measuring both the level of racism and tolerance of the participants (unlike previous studies) we enhance current understanding on egalitarian people’s attitudes toward ethnic outgroups, extending the literature in this regard. Moreover, the inclusion of morality and immorality in our studies allowed us to identify an interesting pattern among non-egalitarian individuals: they show an ingroup bias only for morality and immorality judgments. Therefore, im(morality) is key in the outgroup perception of non-egalitarian individuals in the workplace: they devaluate Moroccans only in this dimension. That is, regardless of how sociable or competent a Moroccan person is perceived, if he or she is not considered sufficiently moral, might be determinant of the expression/manifestation/existence of prejudice. Therefore, we also extend the literature demonstrating the relevance of im(morality) stereotypes in the study of the ethnic prejudice in the workplace in different contexts (i.e., administration and hostelry).

In conclusion, the person’s value system modulates the suppression/expression of prejudice, and the dimension of (im)morality seems especially sensitive in detecting how egalitarian and non-egalitarian participants process information in different ways. Our research contributed by providing a more comprehensive picture on contemporary labor discrimination of ethnic minorities, showing that it is of utmost importance to consider the individuals’ values system along with the targets’ ethnicity to understand how cognitive, affective and action tendencies conform attitudes toward minorities in the workplace.

Data Availability

Raw data, Pooled data, Supplementary Information (SI), Materials used and Preregistrations of Studies 1, 2 and 3 are available in the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/nvy59/?view_only=167d0090cf0a4af8add6f9c0097008d8.

Notes

Raw data, Pooled data, Supplementary Information (SI), Materials used, and Preregistrations of Studies 1, 2 and 3 are available in the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/nvy59/?view_only=167d0090cf0a4af8add6f9c0097008d8. The studies were approved by the authors’ University Ethics Committee.

All analyses were also performed including the participant’s sex, age, and political orientation as covariates. We report the results without including covariates because they did not modify the results consistently. Nevertheless, if the results changed by introducing them, we indicate it.

References

Amirah-Fernández, H. (2015). Relaciones España–Marruecos [Spain–Morocco relations] (Informe Real Instituto Elcano 19). Retrieved from http://www.iberglobal.com/files/2015/Informe-Elcano-Espana-Marruecos.pdf

Agerström, J., Björklund, F., Carlsson, R., & Rooth, D. O. (2012). Warm and competent Hassan = cold and incompetent Eric: A harsh equation of real-life hiring discrimination. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 34(4), 359–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.693438

Arcila-Calderón, C. A., de la Vega, G., & Blanco-Herrero, D. (2020). Topic Modeling and Characterization of Hate Speech against Immigrants on Twitter around the Emergence of a Far-Right Party in Spain. Social Sciences, 9(11), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9110188

Brambilla, M., Sacchi, S., Rusconi, P., & Goodwin, G. (2021). The Primacy of Morality in Impression Development: Theory, Research, and Future Directions. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 64, 187–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2021.03.001

Bracht, G. H., & Glass, G. V. (1968). The external validity of experiments. American Educational Research Journal, 5(4), 437–474. https://doi.org/10.2307/1161993

Brown, R., Eller, A., Leeds, S., & Stace, K. (2007). Intergroup contact and intergroup attitudes: A longitudinal study. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37(4), 692–703. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.384

Conseil de la Communauté Marocaine à l'Étranger, CCME. (2020). Jeunes Marocains d’Europe: égalité et discrimination. Retrieved from the CCME website: https://www.ccme.org.ma/images/activites/fr/2020/ENQUETE_JEUNES_EN_EUROPE.pdf

Crandall, C. S., & Eshleman, A. (2003). A justification-suppression model of the expression and experience of prejudice. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 414–446. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.414

Cuadrado, I., Brambilla, M., & López-Rodríguez, L. (2021a). Unpacking negative attitudes towards Moroccans: The interactive effect of ethnicity and gender on perceived morality. International Journal of Psychology, 56(6), 961–966. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12794

Cuadrado, I., López-Rodríguez, L., Brambilla, M., & Ordóñez-Carrasco, J. L. (2021b, Online First). Active and passive facilitation tendencies at work towards sexy and professional women: The role of stereotypes and emotions. Psychological Reports, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941211058149

Cuadrado, I., López-Rodríguez, L., & Constantin, A. (2020). “A matter of trust”: Perception of morality increases willingness to help through positive emotions. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 23, 462–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430219838606

Cuadrado, I., López-Rodríguez, L., & Navas, M. (2016). La perspectiva de la minoría: Estereotipos y emociones entre grupos inmigrantes [The minority’s perspective: Stereotypes and emotions between immigrant groups]. Anales De Psicología, 32, 535–544. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.2.205341

Cuadrado, I., Ordóñez-Carrasco, J. L., López-Rodríguez, L., Vázquez, A., & Brambilla, M. (2021c). Tolerance towards difference: Adaptation and psychometric properties of the Spanish version of a new measure of tolerance and sex-moderated relations with prejudice. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 84, 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.08.005

Cuddy, A. J., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2007). The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 631–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631

Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Beninger, A. (2011). The dynamics of warmth and competence judgments, and their outcomes in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 31, 73–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2011.10.004

Curran, P. J., & Hussong, A. M. (2009). Integrative data analysis: The simultaneous analysis of multiple data sets. Psychological Methods, 14(2), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015914

Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2004). Aversive racism. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 36, pp. 1–52). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(04)36001-6

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., and Buchner, A. (2007). G∗Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research. Methods, 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

Forscher, P. S., Cox, W. T., Graetz, N., & Devine, P. G. (2015). The motivation to express prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(5), 791–812. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000030

Fuegen, K., Biernat, M., Haines, E., & Deaux, K. (2004). Mothers and Fathers in the Workplace: How Gender and Parental Status Influence Judgments of Job-Related Competence. Journal of Social Issues, 60(4), 737–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00383.x

García-Ael, C., Cuadrado, I., & Molero, F. (2018). The effects of occupational status and sex-typed jobs on the evaluation of men and women. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(1170), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01170

Gastón-Guiu, S., Treviño, R., & Domingo, A. (2021). La brecha africana: desigualdad laboral de la inmigración marroquí y subsahariana en España, 2000–2018 [The African gap: Labor inequality of Moroccan and sub-Saharan immigration in Spain, 2000–2018]. Migraciones, 52, 177–220. https://doi.org/10.14422/mig.i52.y2021.007

Grygoryan, L. (2019). Beyond Us versus Them: Explaining Intergroup Bias in Multiple Categorization. [Published PhD Dissertation] Bremen International Graduate School of Social Sciences. University of Bremen. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335060601_Beyond_Us_versus_Them_Explaining_Intergroup_Bias_in_Multiple_Categorization

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2th ed.). Guilford Press.

Hjerm, M., Eger, M. A., Bohman, A., & Connolly, F. F. (2020). A new approach to the study of tolerance: Conceptualizing and measuring acceptance, respect, and appreciation of difference. Social Indicators Research, 147(3), 897–919. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02176-y

Kite, M. E., & Whitley, B. E. (2016). Psychology of prejudice and discrimination. Routledge.

Kinzler, K. D., Shutts, K., & Correll, J. (2010). Priorities in social categories. European Journal of Social Psycholology, 40, 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.739

Klein, G., & Shtudiner, Z. (2021). Judging severity of unethical workplace behavior: Attractiveness and gender as status characteristics. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 24(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/2340944420916100

Krumpal, I. (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Quality & Quantity: International Journal of Methodology, 47(4), 2025–2047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9

Kulik, C. T., Roberson, L., & Perry, E. L. (2007). The multiple category problem: Category activation and inhibition in the hiring process. The Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 529–548. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159314

Leach, C. W., Ellemers, N., & Barreto, M. (2007). Group virtue: The importance of morality (vs. competence and sociability) in the positive evaluation of in-groups. Journal of personality and social psychology, 93(2), 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.234

Levin, S., Sinclair, S., Veniegas, R. C., & Taylor, P. L. (2002). Perceived discrimination in the context of multiple group memberships. Psychological Science, 13(6), 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00498

López-Rodríguez, L., Cuadrado, I., & Navas, M. (2013). Aplicación extendida del modelo del contenido de los estereotipos (MCE) hacia tres grupos de inmigrantes en España [Extended application of the Stereotype Content Model (SCM) toward three immigrant groups in Spain]. Estudios De Psicología, 34(2), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1174/021093913806751375

Ma, D. S., Correll, J., & Wittenbrink, B. (2015). The Chicago face database: A free stimulus set of faces and norming data. Behavior Research Methods, 47, 1122–1135. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-014-0532-5

Ma, D. S., Kantner, J., & Wittenbrink, B. (2021). Chicago face database: Multiracial expansion. Behavior Research Methods, 53, 1289–1300. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01482-5

McConahay, J. B. (1986). Modern racism, ambivalence, and the modern racism scale. In J. F. Dovidio & S. L. Gaertner (Eds.), Prejudice, discrimination, and racism (pp. 91–125). Academic Press.

Moskowitz, G. B., Gollwitzer, P. M., Wasel, W., & Schaal, B. (1999). Preconscious control of stereotype activation through chronic egalitarian goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.167

Moskowitz, G. B., Salomon, A. R., & Taylor, C. M. (2000). Preconsciously controlling stereotyping: Implicitly activated egalitarian goals prevent the activation of stereotypes. Social Cognition, 18(2), 151–177. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2000.18.2.151

Mullinix, K., Leeper, T., Druckman, J., & Freese, J. (2015). The Generalizability of Survey Experiments. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 2(2), 109–138. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2015.19

Navas, M. S. (1998). Nuevos instrumentos de medida para el nuevo racismo [New measuring instruments for the new racism]. Revista De Psicología Social, 13, 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1174/021347498760350731

Navas, M. S., Cuadrado, I., & López-Rodríguez, L. (2012). Escala de Percepción de Amenaza Exogrupal (EPAE): Fiabilidad y evidencias de validez [Outgroup Threat Perception Scale: Reliability and validity evidences]. Psicothema, 24, 477–482.

Pagliaro, S., Brambilla, M., Sacchi, S., D’Angelo, M., & Ellemers, N. (2013). Initial impressions determine behaviours: Morality predicts the willingness to help newcomers. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(1), 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1508-y

Rama, J., Cordero, G., & Zagórski, P. (2021). Three Is a Crowd? Podemos, Ciudadanos, and Vox: The End of Bipartisanship in Spain. Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 688130. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.688130

Rusconi, P., Sacchi, S., Brambilla, M., Capellini, R., & Cherubini, P. (2020). Being honest and acting consistently: Boundary conditions of the negativity effect in the attribution of morality. Social Cognition, 38, 146–178. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2020.38.2.146

Sayans-Jiménez, P., Rojas, A., & Cuadrado, I. (2017). Is it advisable to include negative attributes to assess the stereotype content? Yes, but only in the morality dimension. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 58, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12346