Abstract

Cosmetic procedures are aimed at enhancing clients’ attractiveness by modifying their physical appearance. Women prefer cosmetic surgery more than men do, due to the ideal of leanness advertised by the media. Female adolescents, undergoing an emotionally unstable developmental stage, are particularly responsive to unrealistic beauty standards. The more they internalize cultural norms, the more they objectify their bodies. Young people’s views on their bodies are essentially influenced by the feedback received from their parents and other adults. The present study explored the impact of caregiver eating messages and objectified body consciousness on the acceptance of cosmetic surgery among Hungarian female students aged 14 to 19 years (M = 16.79, SD = 1.245). Self-report scales used to collect data in four secondary schools. The expected associations were tested with path analysis. Caregiver eating messages generally had an indirect positive impact on the acceptance of cosmetic surgery that was mediated by the shame component of objectified body consciousness. A direct impact was only shown by critical/restrictive caregiver messages and by the shame component of objectified body consciousness. The other two components of objectified body consciousness were unrelated to the acceptance of cosmetic surgery. In sum, caregiver messages on female adolescents’ appearance and eating habits have a formative role on their attitudes towards cosmetic surgery. Such messages predict their proneness to view their bodies as objects serving to meet certain beauty standards. The more they endorse such views, the more they are willing to consider cosmetic surgery to enhance their appearance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Theoretical Background

Cosmetic Procedures

The past decades have witnessed considerable increase in the popularity of cosmetic procedures (Brown et al., 2007; Henderson-King & Henderson-King, 2005) despite the involved risks and irreversible harmful consequences (Ching & Xu, 2019; Markey & Markey, 2009). Cosmetic procedures are elective surgical and non-surgical procedures aimed at enhancing clients’ attractiveness by modifying their physical appearance (Meskó & Láng, 2019; Yazdanparast & Spears, 2018). The essential feature of these surgical interventions is that they are not medically indicated (e.g., Bonell et al., 2021; Earp, 2019; Hyman, 1990; Roscoe, 2018). The literature on the attitude towards cosmetic surgery makes a distinction between three components including social motives, intrapersonal motives, and one’s willingness to consider cosmetic procedure as an option (Henderson-King & Henderson-King, 2005; for the relevant measures, see Instruments below). The intrapersonal factor of motivation for interventions refers to the set of personal benefits expected from cosmetic surgery (e.g., enhancing one’s satisfaction with one’s appearance). The social factor refers the broad social context underlying the person's decision on cosmetic surgery (e.g., enhancing one’s attractiveness to meet one’s partner’s needs). The consider factor refers to the individual’s willingness to consider undergoing cosmetic surgery (e.g., wound healing complications, pain, infections; see Henderson-King & Henderson-King, 2005; Milothridis et al., 2016 for review).

Media have a key importance in the increasing popularity of cosmetic surgery (Arab et al., 2019; Bazner, 2002; Chen et al., 2019; Harrison, 2003; Shome et al., 2020; Swami, 2009; Walker et al., 2019). Consumers receive ample information on the positive aspects of cosmetic procedures (Arab et al., 2019; Ashikali et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2019). By advertising a beauty ideal leaner than the average female body shape (Swami et al., 2008), media indirectly orient consumers towards the available surgical means of meeting unrealistic beauty standards (Bazner, 2002; Harrison, 2003), that are reinforced by strong normative pressures (Shome et al, 2020; Swami et al., 2009). Those who tend to internalize the unrealistic beauty standards advertised by the media are more likely to opt for cosmetic surgery than others (Markey & Markey, 2009). One’s susceptibility to media effects is reflected, among others, in the time spent using social media platforms (Arab et al., 2019; Di Gesto et al., 2021; Shome et al, 2020; Walker et al., 2019).

Empirical findings show that gender is one essential predictor of one’s attitude towards cosmetic surgery (Bazner, 2002; Farshidfar et al., 2013; Meskó & Láng, 2019); women show a much higher preference for cosmetic procedures than men (Bazner, 2002; Brown et al., 2007; Swami et al., 2008). This marked difference reflects gender-related sociocultural pressure (Swami et al., 2009). The unrealistically lean beauty ideal often elicits severe anxiety in women to meet the prevailing standards of physical attractiveness (Harrison, 2003), and thus they feel pressured to undergo cosmetic surgery (Bazner, 2002; Swami et al., 2008).

The attitude towards cosmetic surgery is closely related to body image (Soest et al., 2006) and body satisfaction (Bazner, 2002). Body dissatisfaction is positively associated with the acceptance of cosmetic surgery (Farshidfar et al., 2013; Henderson-King & Henderson-King, 2005; Markey & Markey, 2009), while the more attractive individuals perceive themselves, the less likely they are to undergo some cosmetic intervention (Brown et al., 2007; Swami, 2009). Failing to meet the prevailing beauty standards results in body dissatisfaction, which in turn elicits specific behavioral and psychological responses (Yazdanparast & Spears, 2018). One with high body dissatisfaction views cosmetic surgery as a desirable means of enhancing attractiveness (Swami et al., 2008), thus they are motivated to try such procedures (Yazdanparast & Spears, 2018). Importantly, it is one’s feelings towards one’s body rather than objective physical characteristics (e.g., body weight) that provides the principal motivation for cosmetic surgery (Markey & Markey, 2009).

Objectified Body Consciousness

The unrealistically lean beauty ideal exerts serious sociocultural pressure on women to conform to this ideal (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Swami et al., 2008, 2009). As a result, many women adopt objectifying attitudes towards their own bodies (Forrester-Knauss et al., 2008). They internalize beauty standards and perceive these standards as readily available to them despite the ample conflicting evidence (McKinley & Hyde, 1996). This internalizing tendency is positively associated with objectified body consciousness manifested in relentless self-surveillance and social comparison (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Yazdanparast & Spears, 2018). McKinley and Hyde (1996) described Objectified Body Consciousness including three main components. The first factor—body surveillance—represents rumination and constant self-monitoring from an an outside observer’s perspective to comply with cultural body standards and avoid negative judgments. The second factor—body shame—arises due to the comparison of own body image with cultural standards and the perception of failure to meet those standards. The final factor—appearance control beliefs—refers to those beliefs that individuals are responsible for their bodily look and that, with enough effort their physical appearance is in their control.

Inevitably failing to meet the ideal, most women feel ashamed and anxious about their own bodies (McKinley & Hyde, 1996), and these feelings incline them to consider trying cosmetic surgery (Calogero et al., 2010; Ching & Xu, 2019; Farshidfar et al., 2013; Henderson-King & Henderson-King, 2005). In these terms, shame is a particularly important factor, since it keeps one’s focus on the discrepancy between one’s ideal and real body shape (Yazdanparast & Spears, 2018). In sum, body dissatisfaction in women is a normative phenomenon rather than simply an individual difficulty or mental disorder; it is a common response to the social psychological context in which women live (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; McKinley & Hyde, 1996). Moreover, marked gender differences in body dissatisfaction are observable as early as in adolescence, girls showing clearly higher levels of dissatisfaction (Forrester-Knauss et al., 2008).

Calogero and colleagues (Calogero et al., 2010) found a positive relationship between the acceptance of cosmetic surgery and objectified body consciousness in women. That is, those showing a relatively high preference for cosmetic procedures tended to view their body as an object serving to meet external expectations of physical appearance. Cosmetic surgery seemed to offered them an ideal means of manipulating their appearance. The authors found that the shame component of objectified body consciousness (i.e., the shame associated with body dissatisfaction) uniquely predicted social motives for cosmetic surgery, while self-surveillance uniquely predicted intrapersonal motives. That is, the more often a participant felt ashamed about her appearance in a social situation, and the more dissatisfied she was with her body, the higher preference she showed for cosmetic surgery (Calogero et al., 2010).

These findings were corroborated by Vaughan-Turnbull and Lewis (2015), who found that the acceptance and consideration of cosmetic procedures reported by female participants were positively associated with body objectification, self-surveillance and shame. By contrast, BMI was unrelated to the participants’ attitudes towards cosmetic surgery, which points out the primary importance of one’s feelings about one’s own body in one’s preference for cosmetic procedures (Vaughan-Turnbull & Lewis, 2015). Markey and Markey (2009) also found that BMI is important in women's interest towards cosmetic interventions, but this objective measure alone does not explain this attitude: subjective feelings about one's own body are much more important. A recent study has also showed that BMI did not directly affect the interest in cosmetic surgery, but through the individual’s opinion about their own physical appearance (Seo & Kim, 2020).

Caregiver Messages

Along with cultural factors and the media transmitting the effects of these factors, family environment also has a formative impact on children’s body image and eating behavior. Certain caregiver communications such as eating messages contribute to the development of body dissatisfaction in female adolescents. These eating messages are either restrictive and critical in terms of food intake or press adolescents to eat (Kroon Van Diest & Tylka, 2010). Critical messages are responsible for girls’ body dissatisfaction and desire for leanness. Moreover, such messages lead adolescents to ignore their internal signals informing them of hunger and satiation, which in turn results in disordered eating behavior (Kroon Van Diest & Tylka, 2010) often reaching a clinical level (Oliveira et al., 2019, 2020).

Due to the global tendency towards a lean standard of female beauty, caregiver eating messages to female adolescents are predominantly restrictive and critical. Children’s family environment has a formative impact on their body image and mediates social norms internalized by them (Kroon Van Diest & Tylka, 2010). Frequent eating messages received from the family are a potential precursor of female children’s subsequent body objectification, of their preference for others’ views on their appearance and eating habits over their own views, and of the normative influence of intra- and interpersonal tensions associated with their failure to meet cultural standards (Daye et al., 2014).

Fathers’ messages expressing their attitudes to their female children’s appearance are particularly important in these terms. These messages increase the acceptance of cosmetic surgery in girls by enhancing the social motives for such procedures. This gender-specific effect is probably due to the higher information value of paternal messages as compared to maternal messages in terms of the actual importance of female physical appearance in adult life (e.g., romantic partner choice; Henderson-King & Brooks, 2009). While, of course, mothers also play a formative role in girls’ attitudes towards their own bodies, they primarily fulfil the role of a model. That is, girls acquire these attitudes by observing their mothers’ appearance-related behaviors. The more satisfied and accepting a mother is with her own body, the more positive attitude her daughter will develop to her own physical appearance (McKinley, 1999).

Research Aim

The present study focused on female adolescents. Males were not involved in the study, since previous findings on mixed-gender samples revealed that primarily girls expressed willingness to undergo cosmetic procedures (Swami et al., 2008). Female adolescents are those who most frequently use media advertising an unrealistically lean beauty ideal and the benefits of cosmetic procedures (Chen et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2019). Moreover, adolescence is a developmental stage characterized by emotional instability and high responsiveness to environmental influence and sociocultural pressure (Ching & Xu, 2019). Hence, it is presumable that female adolescents form a subpopulation that is most vulnerable to the harmful effects of the unrealistic beauty standards promoted by the media.

The present study explored the associations of female secondary school students’ attitudes towards cosmetic surgery with the characteristics of the eating messages they received from their caregivers and with their self-objectification propensity. Based on the theoretical introduction, the following hypotheses were formulated.

-

(H1) Caregiver messages were expected to have a direct positive effect on objectified body consciousness and an indirect effect mediated by the latter on their attitudes towards cosmetic surgery (Kroon Van Diest & Tylka, 2010; Oliveira et al., 2019, 2020).

-

(H2) Furthermore, critical/restrictive caregiver messages as opposed to pressure to eat were expected to have a direct effect on the acceptance of cosmetic surgery (Oliveira et al., 2019).

-

(H3) The strongest impact was expected to be shown by the shame component of objectified body consciousness (Calogero et al., 2010; Vaughan-Turnbull & Lewis, 2015; Yazdanparast & Spears, 2018).

-

(H4) Body surveillance was another self-objectification component expected to be an important factor in the model (Calogero et al., 2010; Vaughan-Turnbull & Lewis, 2015).

-

(H5) Appearance control beliefs mean that an individual is convinced that they can control their physical appearance. It was therefore logical to expect that control beliefs would be associated with the acceptance of cosmetic surgery, despite the fact that this relationship has not been previously confirmed (e.g., Bazner, 2002; Calogero et al., 2014; Henderson-King & Henderson-King, 2005).

Method

Participants and Procedure

A total of 196 female secondary students participated in the study. The participants’ age varied between 14 and 19 years (M = 16.79, SD = 1.25). Data were collected by self-report measures in Hungarian secondary schools during classes dedicated to the study. Prior parental consent was received from the parents of all participants under 18 years of age. Participants under 18 years of age submitted a signed declaration of parental consent on the day of participation. These declarations and the participants’ self-report data were collected separately. All participants were informed both in writing and in speech that they were allowed to cease participation at any time without any consequences. The study received ethical approval from the Hungarian United Ethical Review Committee for Research in Psychology (Ref. No. 2018/101).

Instruments

Since only the ACSS had a validated and psychometrically analyzed Hungarian version, the other two questionnaires had to be translated into Hungarian first. The Hungarian versions of the OBCS and CEMS were initially developed using the standard back-translation technique (Brislin, 1980). Specifically, the authors first translated the OBCS and CEMS scales and the instructions into Hungarian, and these versions were then translated back into English by an independent translator unaffiliated with the study. Translators then resolved minor discrepancies that emerged during the back-translation process.

Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale (ACSS; Henderson-King & Henderson-King, 2005; adapted to Hungarian by Meskó & Láng, 2019). The 15-item scale taps one’s attitude towards cosmetic procedures. Respondents rate their agreement with each item on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly disagree (1) to Strongly agree (7). The ACSS comprises the following three subscales: Intrapersonal motives (perceived personal benefits offered by cosmetic surgery as measured by five items) social motives (five items), and consideration (the perceived likelihood of applying for cosmetic surgery in the future; five items). In the present study, the Cronbach’s α values for the Intrapersonal, Social, and Consider subscales were 0.903, 0.896 and 0.920, respectively.

Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (OBCS; McKinley & Hyde, 1996). The 24-item scale assesses women’s personal experiences associated with an objectifying perspective on one’s own body. Respondents rate each item on a six-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly disagree (1) to Strongly agree (6). The OBCS comprises three subscales measuring body surveillance (i.e., constant monitoring of one’s physical appearance), body shame (i.e., a feeling of shame associated with internalized cultural standards of physical appearance), and appearance control beliefs (i.e., controllability of physical appearance). Each subscale is composed of eight items. In the present study, the Cronbach’s α values for Body Surveillance, Body Shame, and Appearance Control Beliefs were 0.694, 0.617 and 0.743, respectively.

Caregiver Eating Messages Scale (CEMS; Kroon Van Diest & Tylka, 2010). The 10-item scale assesses the self-reported impact of caregivers’ eating messages received during childhood. Respondents rate each item on a six-point Likert scale ranging from Never (1) to Always (6) according to how frequently their caregivers emphasized the importance of the described behavior during their childhood. The CEMS comprises two subscales assessing parental pressure to eat (caregivers’ striving to control the child’s eating habits) and critical/restrictive messages (caregivers’ comments on these habits). In the present study, the Cronbach’s α values for Pressure and Critical/Restrictive Messages were 0.813 and 0.821, respectively.

Statistical Data Analysis

Each of the employed measures was tested for normality. Since none of the measures showed normal distribution (all Ws > 0.49, all ps < 0.001), all were treated as ordinal variables in the subsequent analyses. The pairwise associations between the measures were tested with Spearman’s correlation coefficients corrected by Benjamini–Hochberg tests (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). Furthermore, a path analysis was conducted with the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) module of the JASP application. Given the ordinal variables entered in the model, the estimates were based on diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS; Mîndrilã, 2010). The model fit assessment was based on the following indices: The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) were used as relative fit indices, while the χ2statistic, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the square root mean square residual (SRMR) were used as absolute fit indices. The cut-off values for the corresponding model fit were CFI and TLI values of at least 0.95, Chi-square test value below 3 (Hu & Bentler, 1998), and RMSEA and SRMR values of up to 0.08 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993).

Data were analyzed with the IBM SPSS Statistics v22.0 software package and the JASP v0.13.1.0 application.

Results

Preliminary Data Analysis

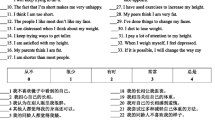

The obtained Spearman’s correlations are presented in Table 1. Of the CEMS, the Critical/Restrictive subscale was positively associated with all three ACSS subscales, whereas Pressure was not related to any of these latter. The Critical/Restrictive subscale was also positively associated with Body Shame but not with either of the other two subscales of the OBCS. The Body Surveillance subscale of the OBCS was positively associated with the Social and Consider subscales of the ACSS, while Body Shame showed positive correlations with all three ACSS subscales. The Appearance Control Beliefs subscale didn’t correlate significantly with any of the other variables (H5). All significant correlations were low to moderate in magnitude.

Model Testing

The tested model (see Fig. 1) is based on the results of the Spearmen correlation analysis and our hypotheses built on previous research findings. The model based on DWLS parameter estimates showed adequate fit with the observed data (N = 196) as indicated by the following fit indices: χ2(762) = 779.428, p = 0.323; χ2/df = 1.023; CFI = 0.998; TLI = 0.998; RMSEA = 0.011 (90% CI = 0.000-0.024); SRMR = 0.074. These fit indices suggest good to excellent fit according to the cutoff values defined previously.

The tested model combined the observed Spearman’s correlations and the expected relationships between caregiver eating messages, body objectification, and acceptance of cosmetic surgery. Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Solid line = tested significant connection, Dotted line = tested nonsignificant connection

Among the expected effects, only that of Pressure on Body Shame was non-significant (β = 0.045, p = 0.152). Critical/Restrictive Messages had a direct positive effect on Body Shame (β = 0.322, p < 0.001) and on all three ACSS subscales including the Intrapersonal (β = 0.108, p = 0.002), Social (β = 0.084, p = 0.026) and Consider subscales (β = 0.122, p < 0.001). Furthermore, Body Shame functioned as a mediator of the indirect positive effect of Critical/Restrictive Messages on the Intrapersonal (β = 0.295, p < 0.001), Social (β = 0.253, p < 0.001) and Consider subscales of the ACSS (β = 0.288, p < 0.001). By contrast, the Surveillance subscale of the OBCS was not associated with either CEMS subscale, while it had a direct positive effect on the Social (β = 0.187, p = 0.005) and Consider subscales of the ACSS (β = 0.121, p = 0.05). The indirect effects of Critical/Restrictive Messages through Body Shame on each ACSS subscale all proved to be significant (Table 2).

The overall explained variances in the three ACSS subscales are as follows. The combined direct and indirect effect of Critical/Restrictive Messages (the latter mediated by Body Shame) accounted for 20.29% of the total variance in the Intrapersonal subscale. The direct effect of Body Surveillance further contributed to the explained variance in the Social and Consider subscales. The model explained 35.25% and 33.57% of the total variance in the Social and Consider subscales, respectively.

Discussion

The obtained results confirmed the expected relationships between measured variables and corroborated previous findings.

In consistence with previous findings (e.g., Oliviera et al., 2019), the two distinct types of caregiver eating messages, that is, pressure to eat vs. critical/restrictive messages proved essentially different in terms of their effects on female adolescents’ attitudes towards their own bodies. Namely, the Pressure subscale of the CEMS was not associated either with the participants’ self-objectification propensity (OBCS) or with their attitudes towards cosmetic surgery (ACSS) (H1). This finding is in line with the conclusion drawn by Kroon van Diest and Tylka (2010), who pointed out that self-reported early caregiver pressure to eat certain types of food or to eat more against one’s own homeostatic needs during childhood was unrelated to one’s body image in adulthood. By contrast, critical/restrictive caregiver messages were associated with one’s attitude both towards one’s own body and towards cosmetic procedures. The self-reported frequency of critical/restrictive caregiver messages was positively associated with body shame (H2). These findings suggest that children internalize familial beliefs about the human body and physical appearance (Kroon van Diest & Tylka, 2010). As a result, children develop an ideal body image, that they continuously strive to achieve. If they fail to meet their internal standards, it is accompanied by negative parental feedback, thus, they experience shame. According to Kroon van Diest and Tylka (2010), restrictive parents strive to exercise normative control over their children’s eating habits and appearance, but their restrictive behavior result in severe backlash, since their children eventually lose touch with their own homeostatic signals and blindly rely on conformity instead.

The obtained results revealed that the feeling of shame associated with objectified body consciousness had a significant direct positive effect on the acceptance of cosmetic surgery, whereas appearance control beliefs related to body weight and shape had no comparable impact. Importantly, body shame was also involved in indirect positive effects leading from caregiver messages to acceptance of cosmetic surgery. Namely, the self-reported impact of critical/restrictive caregiver messages on acceptance of cosmetic surgery was mediated by body shame (H3). This suggests that the early experiences of shame elicited by caregiver eating messages form the developmental basis of adults’ responsiveness to situations potentially involving body shame that in turn increase female adolescents’ willingness to undergo cosmetic surgery. Young women may perceive the prevailing unrealistic beauty standards as negative feedback on their actual physical appearance, which may incline them to conform to the cultural norms of physical attractiveness to gain positive feedback (Markey & Markey, 2009). Repeated experiences of body shame potentially make young women to constantly focus their self-perception on the discrepancy between their ideal and actual body images. This narrowed and negative self-perception will then lead them to fully focus their coping capacity on improving their physical appearance, and they might try cosmetic procedures (Yazdanparast & Spears, 2018). The internalized beauty ideal manifested in negative self-affect provides strong intrinsic motivation for undergoing cosmetic surgery (Henderson-King & Henderson-King, 2005).

Body surveillance (OBCS subscale) was another factor having a direct positive effect on the acceptance of cosmetic surgery, while the observed effect is in part inconsistent with the related previous findings (H4). Specifically, Calogero and colleagues (Calogero et al., 2010) found that body surveillance was associated with the intrapersonal motives for cosmetic surgery, whereas these two factors were unrelated in the present study. The most plausible explanation for this inconsistency lies in the age differences between the university students involved in the former study and the secondary school students involved in the present study, given that the same measures were used in the two studies. In line with Vaughan-Turnbull and Lewis (2015), body surveillance had a positive effect on the consideration of cosmetic surgery, while it was also positively associated with the social motives in the female adolescent sample of the present study. In sum, the more intense body surveillance one engages in, the more likely one is to endorse cosmetic surgery as a means of controlling one’s appearance. Cosmetic procedures enable clients to remove their undesirable and thus worrisome physical features. Since appearance-related anxiety is elicited by social situations, the experiencers are likely to attribute their own anxiety to social pressure, while cosmetic surgery offers an effective means to reduce anxiety.

Critical/restrictive caregiver eating messages had a positive impact on the acceptance of cosmetic surgery that was in part mediated by the shame component of objectified body consciousness. Body surveillance had lesser positive effects on the social motives for, and consideration of cosmetic surgery, which effects were unrelated to the involved adolescents’ childhood experiences. Childhood experiences of parental restrictions on eating habits, appearance-related shame, and intense body surveillance largely contributed to female adolescents’ social motives for cosmetic surgery.

Conclusions

In this study our aim was to explore the associations of Hungarian female secondary school students’ attitudes towards cosmetic surgery with the characteristics of the eating messages they received from their caregivers and with their self-objectification propensity. The novelty of our results can be summarized as follow. Critical/restrictive caregiver messages were positively associated with body shame. Body shame associated with objectified body consciousness had a significant direct positive effect on the acceptance of cosmetic surgery. Appearance control beliefs related to body weight and shape had no comparable impact. The effect of critical/restrictive caregiver messages on acceptance of cosmetic surgery was mediated by body shame. Body surveillance had a direct positive effect on the acceptance of cosmetic surgery. The results of this study can be utilized in practical work to provide guidance for professionals on what areas of life to address with adolescent girls who report high levels of dissatisfaction with their physical appearance.

Limitations and Future Research

Our study has limitations. Although the test sample was satisfactory in size, it would have been advisable to collect a larger sample size for more reliable results. It is a shortcoming that we did not ask the girls for any other demographics other than their age. Among other things, it would have been important and useful to ask about their parents’ relationships during their childhood (for example ‘Did your parents raise you together in a common household as a child?’). The relatively low reliability of OBSC scales is also a limitation to our study. Some items of these scales might be culturally sensitive, thus, in future research not only a sophisticated translation but also a culture-adjusted version of this instrument should be used.

In a future study more demographic data should be requested from subjects. We could get an even more thorough, accurate picture if we could supplement the model tested in the present research with data such as BMI, family socioeconomic status, number of siblings, parental education, family arrangement, and self-satisfaction. In the future, it would also be worthwhile to research what personality factors are associated with openness to cosmetic surgery among adolescent girls.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Arab, K., Barasain, O., Altaweel, A., Alkhayyal, J., Alshiha, L., Barasain, R., ... & Alshaalan, H. (2019). Influence of social media on the decision to undergo a cosmetic procedure. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open, 7(8). https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000002333.

Ashikali, E. M., Dittmar, H., & Ayers, S. (2017). The impact of cosmetic surgery advertising on women’s body image and attitudes towards cosmetic surgery. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 6(3), 255. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000099.

Bazner, J. (2002). Attitudes about cosmetic surgery: gender and body experience. McNair Scholars Journal, 6(1), 3. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair/vol6/iss1/3.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (methodological), 57(1), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x.

Bonell, S., Barlow, F. K., & Griffiths, S. (2021). The cosmetic surgery paradox: Toward a contemporary understanding of cosmetic surgery popularisation and attitudes. Body Image, 38, 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.04.010.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In: Triandis, H. C. and Berry, J. W. (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: methodology (pp. 389–444.). Allyn and Bacon.

Brown, A., Furnham, A., Glanville, L., & Swami, V. (2007). Factors that affect the likelihood of undergoing cosmetic surgery. Aesthetic Surgery Journal, 27(5), 501–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asj.2007.06.004.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage.

Calogero, R. M., Pina, A., Park, L. E., & Rahemtulla, Z. (2010). Objectification theory predicts college women’s attitudes toward cosmetic surgery. Sex Roles, 63(1–2), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9759-5.

Calogero, R. M., Pina, A., & Sutton, R. M. (2014). Cutting words: Priming self-objectification increases women’s intention to pursue cosmetic surgery. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(2), 197–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313506881.

Chen, J., Ishii, M., Bater, K. L., Darrach, H., Liao, D., Huynh, P. P., … Ishii, L. E. (2019). Association between the use of social media and photograph editing applications, self-esteem, and cosmetic surgery acceptance. JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, 21(5), 361–367. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0328.

Ching, B. H. H., & Xu, J. T. (2019). Understanding cosmetic surgery consideration in Chinese adolescent girls: Contributions of materialism and sexual objectification. Body Image, 28, 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.11.001.

Daye, C. A., Webb, J. B., & Jafari, N. (2014). Exploring self-compassion as a refuge against recalling the body-related shaming of caregiver eating messages on dimensions of objectified body consciousness in college women. Body Image, 11(4), 547–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.08.001.

Di Gesto, C., Nerini, A., Policardo, G. R., & Matera, C. (2021). Predictors of acceptance of cosmetic surgery: Instagram images-based activities, appearance comparison and body dissatisfaction among women. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 1–11,. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-021-02546-3.

Earp, B. D. (2019). Mutilation or enhancement? What is morally at stake in body alterations. Practical Ethics. University of Oxford. http://blog.practicalethics.ox.ac.uk/2019/12/mutilation-or-enhancement-what-is-morally-at-stake-in-body-alterations/.

Farshidfar, Z., Dastjerdi, R., & Shahabizadeh, F. (2013). Acceptance of cosmetic surgery: Body image, self esteem and conformity. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 84, 238–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.542.

Forrester-Knauss, C., Paxton, S. J., & Alsaker, F. D. (2008). Body dissatisfaction in adolescent boys and girls: Objectified body consciousness, internalization of the media body ideal and perceived pressure from media. Sex Roles, 59(9–10), 633–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9474-7.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Harrison, K. (2003). Television viewers’ ideal body proportions: The case of the curvaceously thin woman. Sex Roles, 48(5–6), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022825421647.

Henderson-King, D., & Brooks, K. D. (2009). Materialism, sociocultural appearance messages, and paternal attitudes predict college women’s attitudes about cosmetic surgery. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33(1), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.01480.x.

Henderson-King, D., & Henderson-King, E. (2005). Acceptance of cosmetic surgery: Scale development and validation. Body Image, 2(2), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.003.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424.

Hyman, D. A. (1990). Aesthetics and ethics: The implications of cosmetic surgery. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 33(2), 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.1990.0003.

Kroon Van Diest, A. M., & Tylka, T. L. (2010). The caregiver eating messages scale: Development and psychometric investigation. Body Image, 7(4), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.06.002.

Markey, C. N., & Markey, P. M. (2009). Correlates of young women’s interest in obtaining cosmetic surgery. Sex Roles, 61(3–4), 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9625-5.

McKinley, N. M. (1999). Women and objectified body consciousness: Mothers’ and daughters’ body experience in cultural, developmental, and familial context. Developmental Psychology, 35(3), 760. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.3.760.

McKinley, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (1996). The objectified body consciousness scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20(2), 181–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00467.x.

Meskó, N., & Láng, A. (2019). Acceptance of cosmetic surgery among Hungarian women in a global context: The Hungarian version of the Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale (ACSS). Current Psychology, 1–12,. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00519-z.

Milothridis, P., Pavlidis, L., Haidich, A. B., & Panagopoulou, E. (2016). A systematic review of the factors predicting the interest in cosmetic plastic surgery. Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery, 49(03), 397–402. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0358.197224.

Mîndrilã, D. (2010). Maximum likelihood (ML) and diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimation procedures: A comparison of estimation bias with ordinal and multivariate non-normal data. International Journal of Digital Society, 1(1), 60–66. https://doi.org/10.20533/ijds.2040.2570.2010.0010.

Oliveira, S., Marta-Simões, J., & Ferreira, C. (2019). Early parental eating messages and disordered eating: The role of body shame and inflexible eating. The Journal of Psychology, 153(6), 615–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2019.1583162.

Oliveira, S., Pires, C., & Ferreira, C. (2020). Does the recall of caregiver eating messages exacerbate the pathogenic impact of shame on eating and weight-related difficulties? Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 25(2), 471–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0625-8.

Roscoe, L. A. (2018). I feel pretty. Health Communication, 33(8), 1055–1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2017.1323366.

Seo, Y. A., & Kim, Y. A. (2020). Factors affecting acceptance of cosmetic surgery in adults in their 20s–30s. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 44, 1881–1888. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-020-01761-8.

Shome, D., Vadera, S., Male, S. R., & Kapoor, R. (2020). Does taking selfies lead to increased desire to undergo cosmetic surgery. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, 19(8), 2025–2032. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.13267.

Soest, T., Kvalem, I. L., Skolleborg, K. C., & Roald, H. E. (2006). Psychosocial factors predicting the motivation to undergo cosmetic surgery. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 117(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000194902.89912.f1.

Swami, V. (2009). Body appreciation, media influence, and weight status predict consideration of cosmetic surgery among female undergraduates. Body Image, 6(4), 315–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.07.001.

Swami, V., Arteche, A., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Furnham, A., Stieger, S., Haubner, T., & Voracek, M. (2008). Looking good: factors affecting the likelihood of having cosmetic surgery. European Journal of Plastic Surgery, 30(5), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238-007-0185-z.

Swami, V., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Bridges, S., & Furnham, A. (2009). Acceptance of cosmetic surgery: Personality and individual difference predictors. Body Image, 6(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.09.004.

Vaughan-Turnbull, C., & Lewis, V. (2015). Body image, objectification, and attitudes toward cosmetic surgery. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 20(4), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/jabr.12035.

Walker, C. E., Krumhuber, E. G., Dayan, S., & Furnham, A. (2019). Effects of social media use on desire for cosmetic surgery among young women. Current Psychology, 1–10,. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00282-1.

Yazdanparast, A., & Spears, N. (2018). The new me or the me I’m proud of?: Impact of objective self-awareness and standards on acceptance of cosmetic procedures. European Journal of Marketing, 52(1–2), 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-09-2016-0532.

Acknowledgements/Funding

The project has been supported by the European Union, co-financed by the European Social Fund (EFOP-3.6.1.-16–2016-00004—Comprehensive Development for Implementing Smart Specialization Strategies at the University of Pécs).

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Pécs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Őry, F., Láng, A. & Meskó, N. Acceptance of cosmetic surgery in adolescents: The effects of caregiver eating messages and objectified body consciousness. Curr Psychol 42, 15838–15846 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02863-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02863-z