Abstract

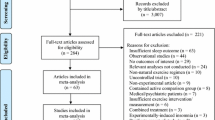

The present study aimed to examine the effects of mindfulness and suppression in the psychological and physiological experience of pain. Fifty-seven chronic pain patients responded to the Weinberger Adjustment Inventory and Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale. Then they were assigned to two groups to suppress or be mindful during the experience of invoked actual pain and participants in each of the two groups were assessed after their respective group intervention. They have reported their pain and distress by Numerical rate scores, and the biofeedback system has assessed their heart rate and the respiratory response. Each group had exposure to a massage device, with results recorded of both exposures to the device and participant psychological recovery (i.e. reporting of pain and distress scores) in the 48-h follow-up. The results showed that there were no differences between groups regarding reporting pain and distress scores immediately and after the 48-h follow-up. However, the mindfulness induction was accompanied by increased activity in the parasympathetic nervous system, and the suppression induction was accompanied by increased activity in the sympathetic nervous system in the cardiovascular and respiratory responses. Also, the suppression induction led to pain sensitivity in the muscular massage experience more than mindfulness induction. The present study provides new evidence for the rebound effects of suppression in revealing pain sensitivity and activation of the sympathetic nervous system. The suppression of pain and feelings increases pain tolerance, while more activation of the sympathetic nervous system leaves patients prone to greater pain sensitivity. Therefore, the induction of mindful attention, may positively alter both the process of developing and reducing chronic pain in patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

Burns, J. W. (2000). Repression predicts outcome following multidisciplinary treatment or chronic pain. Health Psychology, 19(75), 84.

Burns, J. W. (2006). The role of attentional strategies in moderating links between acute pain induction and subsequent psychological stress: Evidence for symptom-specific reactivity among patients with chronic pain versus healthy nonpatients. Emotion, 6, 180–192.

Carlson, L. E., & Brown, K. W. (2005). Validation of the mindful attention awareness scale in a cancer population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58, 29–33.

Cioffi, D., & Holloway, J. (1993). Delayed costs of suppressed pain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(274), 282.

Cowan, C. S., Wong, S. F., & Le, L. (2017). Rethinking the role of thought suppression in psychological models and treatment. Journal of Neuroscience, 37(47), 11293–11295.

Creswell, J. D., & Lindsay, E. K. (2014). How Does Mindfulness Training Affect Health? A Mindfulness Stress Buffering Account. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(6), 401–407.

Derakshan, N., & Eysenck, M. W. (1999). Are repressors self-deceivers or other-deceivers? Cognition & Emotion, 13, 1–17

Ditto, B., Eclache, M., & Goldman, N. (2006). Short-term autonomic and cardiovascular effects of mindfulness body scan meditation. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 227–234.

Dobkin, P. L., & Zhao, Q. (2011). Increased mindfulness – the active component of the mindfulness-based stress reduction program? Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 17, 22–27.

Elfant, E., Burns, J. W., & Zeichner, A. (2008). Repressive coping style and suppression of painrelated thoughts: Effects on responses to acute pain induction. Cognition and Emotion, 22(4), 671–696.

Franklin, Z., Holmes, P., Smith, N. C., & Fowler, N. (2016). Personality Type Influence Attentional Bias in Individuals with Chronic Back Pain. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147035

Gard, T., & Ho¨lzel, B.K., Sack, A.T., Hempel, H., Lazar, S., Vaitl, D., & Ott, U. (2013). Pain Attenuation through Mindfulness is Associated with Decreased Cognitive Control and Increased Sensory Processing in the Brain. Cerebral Cortex, 22, 2692–2702.

Giese-Davis, J., Conrad, A., Nouriani, B., & Spiegel, D. (2008). Exploring emotion-regulation and autonomic physiology in metastatic breast cancer patients: Repression, suppression, and restraint of hostility. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(1), 226–237.

Greeson, J. (2008). Mindfulness research update. Complementary Health Practice Review, 14, 18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533210108329862.

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25.

International Association for the Study of Pain. (2012). Pain terms. Retrieved February 18, 2013, from http://www.iasp-pain.org/Content/NavigationMenu/GeneralResourceLinks/PainDefinitions/default.htm#Pain

Howard, S., Myers, L., & Hughes, B. (2017). Repressive coping and cardiovascular reactivity to novel and recurrent stress. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 30, 562–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2016.1274027

Jamner, L. D., & Schwartz, G. E. (1986). Self-deception predicts self-report and endurance to pain. Psychosomatic Medicine, 48(211), 223.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Delta.

Lambie, J.A., & Baker, K.L. (2003). Intentional avoidance and social understanding in repressors and nonrepressors: Two functions for emotion experience? Consciousness and Emotion, 4, 17_42.

Levenson, R. W. (2014). The automatic nervous system and emotion. Emotion Review, 6(2), 100–112.

Levenson, R. W. (1999). The intrapersonal functions of emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 13(5), 481–504.

McCracken, L. M., Gauntlett-Gilbert, J., & Vowles, K. E. (2007). The role of mindfulness in a contextual cognitive-behavioural analysis of chronic pain-related suffering and disability. Pain, 13, 63–69.

Myers, L. B. (2010). The importance of the repressive coping style: Findings from 30 years of research. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 23, 3–17.

Myers, L. B., Brewin, C. R., & Power, M. J. (1998). Repressive Coping and the directed forgetting of emotional material. Journal ofAbnom1 Psychology, 107, 141–148.

Myers, L. B., Burns, J. W., Derakshan, N., Elfant, E., Eysenck, M. W., & Phipps, S. (2008). Current issues in repressive coping and health. In A. J. Vingerhoets, I. Nyklíˇcek, & J. Denollet (Eds.), Emotion regulation: Conceptual and clinical issues (pp. 69–86). New York: Springer.

Newman, L. S., Duff, K. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (1997). A new look at defensive projection: Thought suppression, accessibility, and biased person perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(980), 1001.

Nyklíˇcek, I., Mommersteeg, P. M., Van Beugen, S., Ramakers, C., & Van Boxtel, G. J. (2013). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and physiological activity during acute stress: A randomized controlled trial. Health Psychology, 32(10), 1110–1113. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032200

Nyklíˇcek, I., Vingerhoets, A., & Denollet, J. (2002). Emotional (non-)expression and health: Data, questions and challenges. Psychology and Health, 17, 517–528.

Raphael, K. G., Marbach, R. M., & Gallagher, R. M. (2000). Somatosensory amplification and affective inhibition are elevated in myofascial face pain. Pain Medicine, 1, 247–253.

Ramezanzade Tabriz, E., Mohammadi, R., Roshandel, G. R., & Talebi, R. (2019). Pain Beliefs and Perceptions and Their Relationship with Coping Strategies, Stress, Anxiety, and Depression in Patients with Cancer. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 25(1), 61–65.

Ryckeghem, D. M., Damme, S., Eccleston, C., & Crombez, G. (2018). The efficacy of attentional distraction and sensory monitoring in chronic pain patients: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.008

Rimes, K., Ashcroft, J., Bryan, L., & Chadler, T. (2016). Emotional Suppression in chronic fatigue syndrome: Experimental study. Health Psychology, 35(9), 979–986.

Saeedi, Z., Ghorbani, N., & Sarafraz, M. (2016). Short form of Weinberger adjustment inventory(WAI): Psychometric properties and confirmatory factor analysis of the Persian version. Journal of Psychological Science, 15, 335–347.

Saeedi, Z., & ghorbani, N., Sarafraz, M., & Karami Shoar, T. (2018). A bias of self-reports among repressors: Examining the evidence for the validity of self-relevant and health-relevant personal reports. International Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12560

Schwartz, G. E. (1990). Psychobiology of repression and health: A systems approach. In J. L. Singer (Ed.), Repression and dissociation (pp. 405–434). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Shapiro, S. L., & Carlson, L. E. (2009). The art and science of mindfulness: Integrating mindfulness into psychology and the helping professions. American Psychological Association.

Sze, J. A., Gyurak, A., Yuan, J. W., & Levenson, R. W. (2010). Coherence between emotional experience and physiology: Does body awareness training have an impact? Emotion, 10(6), 803–814. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020146.

Tamagawa, R., Moss-Morris, R., Martin, A., Robinson, E., & Booth, R. (2013). Dispositional emotion coping styles and physiological responses to expressive writing. British Journal of Health Psychology, 18, 574–592.

Thayer, J., & Lane, R. (2000). A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. Journal of affective disorders. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00338-4.

Treede, R. D., Rief, W., Barke, A., Aziz, Q., Bennett, M. I., Benoliel, R., &, et al. (2019). Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: The IASP classification of chronic pain for the international classification of diseases (ICD-11). Pain, 160, 19–27.

Turk, D. C., Wilson, H. D., & Cahana, A. (2011). Treatment of chronic non-cancer pain. The Lancet, 377(9784), 2226–2235. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60402-9

Uceyler, N., Burgmer, M., Friedel, E., Greiner, W., Petzke, F., Sarholz, M., &, et al. (2017). Etiology and pathophysiology of fibromyalgia syndrome: updated guidelines, overview of systematic review articles and overview of studies on small fiber neuropathy in FMS subgroups. Schmerz (Berlin, Germany), 31, 239–45.

Walsh, J., McNally, M. A., Skariah, A., Butt, A., & Eysenck, M. W. (2015). Interpretive bias, repressive coping, and trait anxiety. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 28(6), 617–633.

Wegner, D. M., & Zanakos, S. (1994). Chronic thought suppression. Journal of Personality, 62, 615–640.

Weinberger, D. A. (1997). Distress and self-restraint as measures of adjustment across the life span: Confirmatory factor analysis in clinical and non-clinical samples. Psychological Assessment, 9, 132–135.

Weinberger, D. A., Schwartz, G. E., & Davidson, R. J. (1979). Low-anxious, high-anxious, and repressive coping styles: Psychometric patterns and behavioral and physiological responses to stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 88, 369–380.

Weinberger, D. A., & Schwartz, G. E. (1990). Distress and restraint as superordinate dimensions of self-reported adjustment: A typological perspective. Journal of Personality, 58(38), 1–417.

Wenzlaff, R. M., & Wegner, D. M. (2000). Thought suppression. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 59_91

Zeidan, F., Gordon, N. S., Merchant, J., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). The effects of brief mindfulness meditation training on experimentally induced pain. Journal of Pain, 11, 199–209.

Zeidan, F., Martucci, K. T., Kraft, R. A., Gordon, N. S., McHaffie, J. G., & Coghill, R. C. (2011). Brain mechanisms supporting the modulation of pain by mindfulness meditation. Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 5540–5548.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Discussion

The present study showed that there was no difference between the suppression induction and mindfulness induction groups in terms of reporting pain and distress in the seven stages of the experiment and follow-up. Even though there are differences in heart rate, respiration rate, and abdominal respiration amplitude between intervention groups in the clinic. Also, the suppression induction group appraised the massage experience as more painful and more unpleasant than the mindfulness induction group.

The same report of pain and distress between the two groups could be due to the short-term therapeutic effects of suppression (Cowan et al., 2017), which is as effective as mindfulness induction in reducing pain and distress in patients. Cioffi and Holloway (1993; Ryckeghem et al., 2018) revealed that suppressing pain-related thoughts is no different from other cognitive strategies that affect pain sensitivity in the short term but will lead to the formation of several long-term effects. The same result was found in the higher sensitivity suppression induction group during the experience of muscle massage in this study.

Considering the differences in physical indices despite no difference in reporting pain and distress in the chronic pain patients, it seems perhaps patients with chronic pain as a group usually avoiding or inhibiting conflicting emotions (Raphael et al., 2000) may have repressed or suppressed their pain symptoms or feelings and did not report accurately their pain and distress in self-reports, while different scores on physical indices may have shown the actual difference in the experience of the two groups. In other words, although the differences in the self-report scales of the chronic pain patients were not significant, the physiological parameters measured differed between the two intervention groups. Thus, it seems that the interventions performed may have made a positive difference between the two groups, but patients with chronic pain did not report this difference in the self-report scales. This finding is consistent with the discrepancy that is often observed (Weinberger et al., 1979) between self-report anxiety and physiological and behavioral arousal in repressors (Myers et al., 2008). The simplest explanation of the discrepancies between the self-reports and the behavioral or physiological measures is that repressors experience high levels of anxiety but deny this in their self-reports. If this were the case, repressors’ levels of experienced anxiety would be consistent with their levels of behavioral and physiological anxiety (Derakshan & Eysenck, 1999 as cited in Walsh et al., 2015).

From many evolutionary/functional perspectives, the mental experience of emotion is not the main characteristic of emotion, but the biosensor information that determines changes in temperature, pressure, body posture, muscle tension, and movement (Levenson,1999 as cited in Levenson, 2014) And the highest correlation between subjective experience and physiology is seen in subjects with a deep experience of Vipassana meditation (with a deep focus on inner states) (Sze, Gyurak, Yuan, & Levenson, 2010 as cited in Levenson, 2014). This consistency is very important in emotion theories and is associated with health and well-being (Levenson, 2014).

However, the respiratory status in this study showed that those who received the suppression induction intervention took more superficial breaths during the intervention and the patients who received the mindfulness induction intervention had deeper and slower breathing; both groups were close to the baseline respiratory status after the intervention. Both groups showed an increased respiratory rate and decreased amplitude at the time of the muscle massage. This pattern indicates that the suppression induction disrupted the autonomic system's balance (activation of the sympathetic system of patients) and the mindfulness induction led to a better balance of the autonomic system (activation of the patients' parasympathetic system) in the cardiac and respiratory states. Besides, a similar pattern of breathing during the muscle massage task indicated that this stimulus was somewhat anxious for both groups and activated the sympathetic system in both groups. These findings are consistent with studies showing that mindfulness training can inhibit the sympathetic nervous system response to acute stress (Nyklíˇcek et al., 2013) and lead to increased parasympathetic nervous system activity (Ditto et al., 2006).

Thayer and Lane (2000 as cited in Creswell & Lindsay, 2014) revealed that mindfulness can: 1) reduce sympathetic-nervous-system activation and its principle stress effectors (secretion of the catecholamines norepinephrine and epinephrine), or 2) lead to increased activity in the parasympathetic nervous system, which can slow-down the sympathetic-nervous-system fight-or-flight stress responses via the vagus nerve.

The findings of this study also showed that the heart rate of the suppression induction group was higher than the heart rate of the mindfulness induction group. Indeed, suppression induction is one of the predictors of increased physiological response (Burns, 2006), and the suppression of emotion is associated with physiological indices such as increased heart rate and decreased skin conductance resistance (Myers et al., 2008) and increased risk of cardiovascular disease development through elevated cardiovascular reactions to both novel and recurrent stress (Howard et al. 2017).

It seems that a brief intervention through the suppression of emotion and thought can disrupt the autonomic nervous system balance and activate the sympathetic nervous system in patients. Perhaps repressors who are chronic thought suppressors (Wegner & Zanakos, 1994) and habitually suppress awareness of these feelings will be subject to many physical illnesses. Repressors may not be aware of their physical states and symptoms (Schwartz, 1990), But the long-term consequence of this increased autonomic nervous system activity may increase risk of many health problems (Myers et al., 2008). However, repressors, despite their lower reports of health problems, usually indicate more autonomic nervous system abnormalities (Giese-Davis et al., 2008).

Also, a brief intervention through mindful attention to emotion and thoughts can activate the parasympathetic nervous system of chronic pain patients, for whom avoidance and inhibition are characteristics (Raphael et al., 2000). Long term therapeutic mindfulness programs focusing on the characteristic of the repressive coping style (which can lead to more sympathetic nervous activity and more physical problems) can play an important role in improving the health of these individuals.

Also, in the experience of muscle massage, when the patients suppressed the experience of physical pain and attempted to deliberately suppress their internal stimuli, in the first step, apparently they calmed themselves down by ignoring their internal stimuli, but in the next step, without wanting to devote part of their mind to spamming unwanted content, the availability of unfavorable thoughts increased under the “ironic process model” (Wegner and Zanakos, 1994). And paradoxically, sensitivity to pain increases over time through the unconscious monitoring system. This study, consistent with the study by Elfant et al. (2008), has shown that participants in the suppression induction group were generally less responsive than the other group during the recovery and massage periods. Conversely, when a chronic pain patient tried to eagerly observe and accept their pain, emotions, feelings, and thoughts during the pain experience—without the tendency to change or control internal stimuli and allowing them to be processed—they could also try to experience this new physical stimulation and whatever was going on from moment to moment when they received the muscle massage, rather than relying on previous experiences of pain or fear of physical stimulation.

Studies have shown that meditation training, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction, can reduce pain symptoms and increase psychological well-being. (McCracken et al., 2007) and in the case of laboratory-induced pain, short-term meditation interventions lead to greater tolerance, less pain, and distress compared to control groups (Zeidan et al., 2010). Also, drawing attention to painful stimuli, in particular to their objective / sensory dimensions, can lead to less pain perception (Gard et al., 2013). Also, suppression and repression of experience are associated with activation of the sympathetic nervous system and increase the possibility of experiencing pain and physical sensitivity, while mindfulness is associated with the activation of the parasympathetic system and greater experience of pleasant emotions.

Studies have shown characteristic traits could moderate the effectiveness of experimental interventions on pain (Elfant et al., 2008). The importance of this study was showing the role of suppression and mindfulness induction on the experience of pain with controlling the trait of repressive coping style and mindfulness. In other words, this study has attended characteristic individual differences, while assessing the effectiveness of interventions on pain.

It seems overall relief from pain is an unrealistic goal. Therapists should focus on improving the pain-related distress and patients functioning. Pain-management protocols can avoid chronic pain through accepting and moment-to-moment attention to any pain. By activating the parasympathetic system in pain patients and breaking the vicious circle of pain suppression, they can take a fundamental step in reducing the distress and pain sensitivity caused by pain. Therefore, it can prevent and decrease the possible formation of chronic pain.

This study had some limitations; it was not possible to screen repressor patients from a large sample. Then to control the repressive coping style, we had to statistically control for this personality trait. And in the follow-up phase, it was not possible to measure physiological indices, and the follow-up data were limited to patients' self-reports. Similar further studies should be carried out with other samples to evaluate the effectiveness of mid-term and long-term mindfulness training, taking into account a repressive coping style, in the psychological and physical experience of pain. Also, a comparison of the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions on repressor and non-repressor pain patients is another suggestion. Besides, it is suggested that to increase the generalizability of the results, similar studies should be conducted with other samples with different demographic characteristics.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript and there is no financial interest to report. We certify that the submission is original work and is not under review at any other publication. Approval was obtained from the University of Tehran ethics committee and the informed consent was written by participants. Also, datasets are available.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saeedi, Z., Ghorbani, N., Shojaeddin, A. et al. The experience of pain among patients who suffer from chronic pain: The role of suppression and mindfulness in the pain sensitivity and the autonomic nervous system activity. Curr Psychol 42, 15539–15548 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02849-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02849-x