Abstract

Motivation plays a key role in the physical-sports field, in the control of disruptive states and in the mental image that people have of themselves. In view of the above, the present study reflects the objectives of identifying and establishing the relationship between sport motivation, anxiety, physical self-concept and social self-concept, broken down into (a) developing an explanatory model of sport motivation and its relationship with anxiety and social and physical self-concept and (b) contrasting the structural model by means of a multi-group analysis according to sex. To this end, a quantitative, non-experimental (ex post facto), comparative and cross-sectional study was carried out on a sample of 556 students (23.06 ± 6.23). The instruments used were an ad hoc questionnaire, the Spanish version of the Perceived Motivational Climate in Sport Questionnaire (PMCSQ-2), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and the Self-Concept Form-5. The results show that the male sex orients sport motivation towards climate, obtaining higher levels of anxiety, however, the female sex, anxiety has a negative impact on the development of social self-concept. In conclusion, it can be affirmed that gender is a fundamental factor in the orientation of sport practice, as well as the development of anxiety and physical and social self-concept.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Currently, motivation is one of the most studied psychological aspects to explain different human behaviours. This concept can be defined as the result of the interaction between different factors (biological, cognitive, emotional and social) that determine the choice, intensity, persistence and performance towards a given task (Conde-Pipó et al., 2021; Ramírez-Granizo et al., 2020).

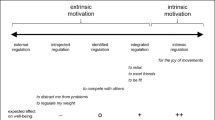

The study of motivation in the physical-sports field has been determined by two theories. The first of these is that proposed by Nicholls (1989), known as Achievement Goal Theory, which states that people set different objectives during physical-sports practice, which are related to the perception that the subject has of his or her own abilities, therefore, the goal pursued can be oriented towards motivational climates directed towards the task or the ego (Claver et al., 2020). When the motivation originates from the task climate, it will be oriented towards higher levels of effort to learn and the enjoyment of the practice of the task (Bardach et al., 2020), nevertheless, when the climate is oriented towards the ego, values such as greater social recognition achieved through competition in the sporting context acquire greater presence (González-Valero et al., 2017). The second theory was proposed by Deci and Ryan (1985) and is the self-determination theory, where it is established that when sport practice is oriented towards the task climate, intrinsic values acquire greater importance, while if sport practice is oriented towards the ego climate, extrinsic motivations acquire greater importance (Castro-Sánchez et al., 2018).

Another factor that plays a fundamental role is anxiety, which can be defined as a negative psycho-emotional state, where feelings such as worry or nervousness predominate (Gao et al., 2020; Weinberg & Gould, 1996). In the university context, many students live with high levels of anxiety caused by achieving the highest possible academic performance (Gustems-Carnicer et al., 2019), however, the study by Kayani et al. (2021) establishes that the practice of physical exercise oriented towards intrinsic motivations helps to reduce anxiety levels. Nevertheless, the study by Castro-Sánchez et al. (2019) found that when a sport begins to be performed in a professional manner, there is an increase in anxiety, due to participants focus on competitiveness, obviating the enjoyment and fun of it.

Self-concept is defined by Chen et al. (2021) as a mental construct that the subject has of him/herself when interacting with the environment around himself/herself. According to the theoretical model proposed by Shavelson et al. (1976), self-concept is represented as a multidimensional construct with five areas: academic, emotional, family, physical and social. Focusing attention on these last two types, social self-concept can be defined as the perception that each subject has of himself/herself about his/her social skills with respect to interactions with peers (Lindell-Postigo et al., 2020) and physical self-concept is defined as the perception that people have of their physical appearance (Putnick et al., 2020). The study carried out by Fernández-Bustos et al. (2015), argues that physical self-concept has an impact on social self-concept, as certain social groups carry out a discriminatory process based on perceived physical appearance.

This study presents the following research questions: Does orienting motivation towards ego-climate or task-climate influence the development of anxiety and physical and social self-concept? Does anxiety contribute negatively to physical and social self-concept? Does physical self-concept help the development of social self-concept? Are there differences regarding sex? Following the issues and questions raised, the following hypotheses are proposed:

-

Orienting sport motivation towards the ego-climate or task-climate will affect the development of anxiety and physical and social self-concept.

-

Anxiety impairs the development of physical self-concept and social self-concept.

-

Physical self-concept helps the development of social self-concept.

-

Males will have higher ego-climate ratings and higher levels of physical and social self-concept than females. Female sex will show higher levels of anxiety than male sex.

Finally, the present research aims to identify and establishing the relationship between sport motivation, anxiety, physical self-concept and social self-concept according to sex, breaking down into (a) developing an explanatory model of sport motivation and its relationship with anxiety and social and physical self-concept and (b) contrasting the structural model by means of a multi-group analysis according to sex.

Matherial and Methods

Subjects and Design

A non-experimental (ex post facto), descriptive and cross-sectional study was carried out on students of the Faculty of Education Sciences of the University of Granada. The study sample consisted of 556 students, with 75% female (n = 417) and 25% male (n = 139). The students were aged between 18 and 24 years (23.06 ± 6.23). The subjects participated on a voluntary basis after receiving an explanation of the objectives and nature of the study, giving their written informed consent. Continuing with the sampling error, a sampling error of 0.05 was assumed, taking into account a random sampling by natural groups, giving an error of 0.048 with a confidence interval of 95%.

Instruments and Variables

-

Sociodemographic questionnaire, which is an ad-hoc questionnaire to collect data that involved gender (male or female) and age.

-

Perceived Motivational Climate in Sports Questionnaire (PMCSQ-2), developed by Newton et al. (2000), but the Spanish version of the instrument (González-Cutre et al., 2008) was used for this research. This questionnaire is made up of 33 items rated on a five-level Likert scale (1 = totally disagree and 5 = totally agree), and evaluates motivation within two dimensions: task-oriented climate (which comprises three sub-dimensions: effort, improvement and cooperative learning), and ego-oriented climate (which is composed of three sub-levels: unequal recognition, punishment for mistakes and intra-team rivalry) While internal reliability of task-oriented climate was 0.925, the one for ego-oriented climate was 0.912.

-

Beck Inventory Anxiety, developed by Beck et al. (1988), but for this study it has been used the Spanish version adapted by Sanz and Navarro (2003). This questionnaire is made up of a total of 21 items, which are measured on a four-level Likert-type scale (0 = not at all and 3 = severely). To obtain the final score, the items have to be summed up, classifying the responses into minimal anxiety (0 to 9 points), mild anxiety (10 to 18 points), moderate anxiety (19 to 29 points) and severe anxiety (30 to 63 points) (Sanz & Navarro, 2003). For this research, Cronbach's Alpha obtained a score of 0.936.

-

Self-concept Form 5, developed by García and Musitu (1999) but the version of Zurita-Ortega et al. (2021) has been used for the present research. It measures self-concept by using a five-level Likert scale (1 = never and 5 = always), and comprises items grouped in five dimensions: academic self-concept (A-SC: items 1, 6, 11, 16, 21, 26), social self-concept (S-SC: items (2, 7, 12, 17, 22, 27), emotional self-concept (E-SC: items 3, 8, 13, 18, 23, 28), and physical self-concept (P-SC: items 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30). In this case, for the social self-concept a reliability of 0.810 was obtained, while for the physical self-concept a reliability of 0.855 was obtained.

Procedure

First of all, a bibliographical review was carried out to gather information and understand the problematic situation in the different societies. Afterwards, the Department of Didactics of Musical, Plastic and Corporal Expression of the University of Granada (Spain) created a Google form with the instruments specified above, establishing the objective of the study and the acceptance of participation by sending the form. Various ways were used to send the form, but social networks of the Department of Didactics of Musical, Plastic and Corporal Expression (Facebook, Instagram and Whatsapp) were used for the most part. In addition, two questions were duplicated to ensure that the questionnaires were not completed randomly, however, 28 had to be deleted as they were completed incorrectly. In line with ethical principles, the principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed at all times, guaranteeing anonymity and respecting the rights of the participants. In addition, an Ethics Committee of the University of Granada approved the research (1230/CEIH/2020).

Data Analysis

For the statistical analysis of the results, the IBM SPSS Statics 25.0 programme (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used. A descriptive analysis of the data was carried out using frequencies and means. For the comparative analysis, a T-Students test for independent samples was used and statistically significant differences were determined by means of Pearson's Chi-Square test, establishing the reliability index at 95%. The magnitude of the difference in effect size (ES) was obtained with Cohen's standardised d-index (Cohen, 1992), interpreted as null (0.0–0.19), small (0.20–0.49), medium (0.50–0.79) and large (≥ 0.80). Finally, to study the normality of the data, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was performed, obtaining a normal distribution.

The IBM SPSS Amos 26.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to create the multigroup structural equation model, which allows to establish relationships between the variables that make up the theoretical model (Fig. 1) for male and female genders. Likewise, a general model was developed for the study sample and two clearly differentiated models to verify the relationships of the variables according to the gender of the participants. In this case, the proposed models have eight endogenous variables and three exogenous variables. For the endogenous variables causal explanations were made considering the observed associations between indicators and measurement reliability, therefore, measurement error of observable variables was included in the model and could be controlled and interpreted as multivariate regression coefficients. One-way arrows represented lines of influence between latent variables and were interpreted from regression weights. A significance level of 0.05 was established using Pearson's Chi-square test.

Theoretical model proposed. Note: Task-oriented Climate (TC); Cooperative Learning (CL); Effort/Improvement (EI); Important Role (IR); Ego-oriented Climate (EC); Punishment for Mistakes (PM); Unequal Recognition (UR); Member Rivalry (MR); Anxiety (ANX); Physical Self-Concept (P-SC); Social Self-Concept (S-SC)

In this case, the physical self-concept variable acts as an endogenous variable, where it is affected by task-oriented climate, ego-oriented climate and anxiety. Likewise, the social self-concept variable acts as an endogenous variable and is affected by task climate, anxiety, ego climate and physical self-concept.

Finally, the model fit was evaluated after estimating the different parameters of the model. Following the recommendations of Bentler (1990), and McDonald and Marsh (1990), the goodness of fit should be assessed on the basis of Chi-square, whose associated p-values, not significant, indicate a good model fit, Comparative Fit Index (CFI; values above 0.95 indicate a good model fit), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI; values above 0.90 indicate an acceptable fit), Incremental Fixity Index (IFI; values above 0.90 indicate an acceptable fit) and Root Mean Square Approximation (RMSEA; values below 0.1 indicate an acceptable model fit).

Results

Looking at the results of the correlational analysis, (Table 1) focusing on cooperative learning (CL), positive relationships are observed with effort improvement (EI) (r = 0.727), important role (IR) (r = 0.786), physical self-concept (P-SC) (r = 0.215) and social self-concept (P-SC) (r = 0.249), however, negative relationships are obtained with punishment for mistakes (PM)(r = -0.363), unequal recognition (UR) (r = -0.395) member rivalry (r = -0.073) and anxiety (ANX) (r = -0.185). Continuing with effort improvement (EI), positive relationships are observed with important role (IR) (r = 0.766), physical self-concept (P-SC) (r = 0.219) and social self-concept (S-SC) (r = 0.210), and negative relationships with punishment for mistakes (PM) (r = -0.400), unequal recognition (UR) (r = -0.394), member rivalry (MR) (r = -0.116) and anxiety (ANX) (r = -0.222). Important role (IR) shows positive relationships with physical self-concept (P-SC) (r = 0.186) and social self-concept (S-SC) (r = 0.224), however, negative relationships are evident with punishment for mistakes (PM) (r = -0.381), unequal recognition (UR) (r = -0.417), member rivalry (MR) (r = -0.123) and anxiety (ANX) (r = -0.198). Moving on to punishment for mistakes (PM), positive relationships are observed with unequal recognition (UR) (r = 0.742), member rivalry (MR) (r = 0.494) and anxiety (ANX) (r = 0.236), however, negative relationships are obtained with physical self-concept (P-SC) (r = -0.080) and social self-concept (S-SC) (r = -0.090). Continuing with unequal recognition (UR), positive relationships are obtained with member rivalry (MR) (r = 0.524) and anxiety (ANX) (r = 0.184), and negative relationships with physical self-concept (P-SC) (r = -0.091) and social self-concept (S-SC) (r = -0.106). Going on to member rivalry (MR), positive relationships are observed with anxiety (ANX) (r = 0.080), physical self-concept (P-SC) (r = 0.118) and social self-concept (S-SC) (r = 0.059). Continuing with anxiety (ANX), negative relationships are observed with physical self-concept (P-SC) (r = -0.331) and social self-concept (S-SC) (r = -0.154). Finally, social self-concept is positively related to physical self-concept (r = -0.326).

The results obtained in the comparative analysis (Table 2) show that the female sex (M = 0.083) has higher scores in anxiety (ANX) than the male sex (M = 0.67). Also, in cooperative learning (CL), effort, improvement (EI) and important role (IR) the female sex shows higher scores (M = 4.04; M = 3.96; M = 4.08) than the male sex (M = 3.90; M = 3.96; M = 3.95). Continuing with punishment for mistakes (PM), unequal recognition (UR) member rivalry (MR), the male sex shows higher scores (M = 2.46; M = 2.67; M = 2.85) than the female (M = 2.36; M = 2.63; M = 2.64). For physical self-concept (P-SC) and social self-concept (S-SC), the male gender shows higher ratings (M = 3.41; M = 3.43) than the female gender (M = 3.02; M = 3.42).

The model proposed and developed through the variables assessed in a sample of undergraduate students between 18 and 24 years of age showed a good fit for all indices. The Chi-square analysis showed a significant p-value (\({X}^{2}=\) 76,550; df = 20; pl = 0,000), however, these data cannot be interpreted in an independent way due to the influence of sample size and susceptibility (Tenenbaum & Eklund, 2007), therefore, other standardised fit indices have been employed which were also less sensitive to sample size.

The comparative fit index (CFI) analysis obtained a value of 0.973, which represents an excellent score. The normalized fit index (NFI) analysis obtained a value of 0.964, the incremental fit index (IFI) was 0.973 and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) obtained a value of 0.951, all of which were excellent. In addition, the root mean square error of approximation analysis (RMSEA) also obtained a value of 0.048.

Figure 2 and Table 3 show the regression weights of the theoretical model, with relationships statistically significant at p < 0.001. Anxiety (ANX) was negatively associated with physical self-concept (P-SC) (p < 0.001; r = -0.311) and task-oriented climate (TC) (p < 0.001; r = -0.199), however, it showed a positive relationship with ego-oriented climate (EC) (p < 0.001; r = 0.227). Focusing attention on task- oriented climate (TC), a positive relationship was obtained with physical self-concept (P-SC) (p < 0.001; r = 0.219), social self-concept (S-SC) (p < 0.001; r = 0.203), effort/improvement (EI) (p < 0.001; r = 0.844), cooperative learning (CL) (p < 0.001; r = 0.866), however, a negative relationship was found between task-oriented climate (TC) and ego-oriented climate (EC) (p < 0.001; r = -0.496). Focusing attention on ego-oriented climate (EC), a positive relationship was observed with unequal recognition (UR) (p < 0.001; r = 0.890) and member rivalry (MR) (p < 0.001; r = 0.590). Finally, in terms of physical self-concept (P-SC), there was a positive relationship with social self-concept (S-SC) (p < 0.001; r = 0.271).

Structural equation for the theoretical model. Note: Task-oriented Climate (TC); Cooperative Learning (CL); Effort/Improvement (EI); Important Role (IR); Ego-oriented Climate (EC); Punishment for Mistakes (PM); Unequal Recognition (UR); Member Rivalry (MR); Anxiety (ANX); Physical Self-Concept (P-SC); Social Self-Concept (S-SC)

The model developed according to male gender showed good scores for each of the indices. The Chi-square analysis showed a significant p value (\({X}^{2}=\) 38,276; df = 20; pl = 0,008). The comparative fit index (CFI) analysis showed a rating of 0.966, the normalised fit index (NFI) gave 0.964 and the incremental fit index (IFI) was 0.967. Focusing on the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), a value of 0.952 was obtained while the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) scored 0.051.

Figure 3 and Table 4 show the regression weights of the theoretical model with relationships statistically significant at p < 0.001. Anxiety (ANX) shows a negative relationship with physical self-concept (P-SC) (p < 0.001; r = -0.297) and task-oriented climate (TC) (p < 0.001; r = -0.397), however, it shows a positive relationship with ego-oriented climate (EC) (p < 0.001; r = 0.433). Focusing attention on task-ego climate (TC), it has a positive relationship with effort/improvement (EI) (p < 0.001; r = 0.872) and cooperative learning (CL) (p < 0.001; r = 0.870), however, it shows a negative relationship with ego-oriented climate (EC) (p < 0.001; r = -0.447). In terms of ego-oriented climate (EC), positive relationships were observed between unequal recognition (UR) (p < 0.001; r = 0.820) and member rivalry (MR) (p < 0.001; r = 0.509). Finally, physical self-concept (P-SC) is positively related to social self-concept (S-SC) (p < 0.001; r = 0.373).

The structural equation for male gender. Note: Task-oriented Climate (TC); Cooperative Learning (CL); Effort/Improvement (EI); Important Role (IR); Ego-oriented Climate (EC); Punishment for Mistakes (PM); Unequal Recognition (UR); Member Rivalry (MR); Anxiety (ANX); Physical Self-Concept (P-SC); Social Self-Concept (S-SC)

Lastly, for female gender, Chi-square analysis showed a significant p-value (\({X}^{2}=\) 70,876; df = 20; pl = 0,000). The comparative fit index (CFI) analysis scored 0.966, the normalised fit index (NFI) scored 0.966 and the incremental fit index (IFI) resulted 0.976. Focusing on the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), a value of 0.956 was obtained while the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.041.

Figure 4 and Table 5 show the regression weights of the theoretical model, with statistically significant relationships at p < 0.001. Anxiety (ANX) shows a negative relationship with physical self-concept (P-SC) (p < 0.001; r = -0.279) and task-oriented climate (TC) (p < 0.001; r = -0.169), however, for ego-oriented climate (EC) it showed a positive relationship (p < 0.001; r = 0.236). Continuing with task-oriented climate (TC), it is observed that it has positive relationships with physical self-concept (P-SC) (p < 0.001; r = 0.235), social self-concept (S-SC) (p < 0.001; r = 0.204), effort/improvement (EI) (p < 0.001; r = 0.844), cooperative learning (CL) (p < 0.001; r = 0.866), however, it shows a negative relationship with ego-oriented climate (EC) (p < 0.001; r = -0.495). In terms of ego-oriented climate (EC), it shows positive relationships with unequal recognition (UR) (p < 0.001; r = 0.892) and member rivalry (MR) (p < 0.001; r = 0.575). Finally, physical self-concept (P-SC) showed a positive relationship with social self-concept (S-SC) (p < 0.001; r = 0.259).

The structural equation for female gender. Note: Task-oriented Climate (TC); Cooperative Learning (CL); Effort/Improvement (EI); Important Role (IR); Ego-oriented Climate (EC); Punishment for Mistakes (PM); Unequal Recognition (UR); Member Rivalry (MR); Anxiety (ANX); Physical Self-Concept (P-SC); Social Self-Concept (S-SC)

Discussion

The present study shows the relationships between the motivation developed towards the physical-sports environment on the control of anxiety and the development of physical and social self-concept in university students. The results obtained respond to the initially stated objectives and therefore, the present discussion follows the line of comparing the data obtained with those of another research carried out. With a similar nature to that of the present study, the researches carried out that relate motivational, sporting and psychosocial aspects stand out (Orris et al., 2020; Ramírez-Granizo et al., 2020; Ruffault et al., 2020).

The comparative analysis shows that the female sex obtains higher levels of anxiety than the male sex. In view of these findings, Mascret et al. (2019) state that the academic environment is a favourable element due to the anxiety derived from the fear of academic failure, with the female sex bearing the brunt of this disruptive state. In terms of the motivational climate, specifically the variables that make up the ego climate, higher scores are observed for the male sex. Zurita-Ortega et al. (2017a, b), state that the female sex is more conducive to collaborative work, where peers and the process to be followed to achieve an established objective are valued equally; however, the male sex gives more importance to competing and achieving greater social recognition. In terms of physical self-concept, higher scores were observed for males than for females. Similar results were obtained by Kozina (2019), affirming Martínez-Marín et al. (2021) that the female sex is subjected to greater social pressures for body care, which can generate a feeling of rejection towards physical form if it does not conform to these pressures.

According to the general theoretical model proposed for university students, it is observed that when physical-sports practice is oriented towards the ego climate, positive relationships are observed between both variables; however, when it is oriented towards the task climate, a decrease in the levels of this disruptive state is fostered. Similar results were obtained by Castro-Sánchez et al. (2019) where they state that when a sport is carried out professionally, anxiety levels increase due to the high degree of competitiveness, nevertheless, Dimas et al. (2021) argue that when the practice of physical exercise is oriented towards fun and maintaining a non-sedentary lifestyle, there is a decrease in anxiety levels, attributing this effect to the secretion of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine (Ubago-Jiménez et al., 2020).

Likewise, a negative relationship is also observed between anxiety and the development of physical and social self-concept, with a lower level of correlation for the latter. Dolenc (2019) states that anxiety can affect students' own body image of themselves, as studies carried out by Marchena et al. (2020) and Trigueros et al. (2020) state that when subjects are subjected to negative emotions or disruptive moods, many of them carry out a process of emotional overfeeding. According to the study by Piccirillo et al. (2021), social self-concept is affected by the social interactions carried out. Due to the health crisis caused by COVID-19, the number of social interactions has been limited to avoid the spread of COVID-19 (Voulgaridou & Kokkinos, 2020), affecting the development of social self-concept (Freitas et al., 2021).

In terms of gender differences, for both gender, there are positive relationships between ego climate and anxiety and task-climate and this disruptive state, with higher values for the male gender. Similar results were obtained by Merino-Fernández et al. (2020), where they found that the female gender shows lower levels of anxiety when practising physical exercise, as they have more training in techniques for channelling moods and emotions of a disruptive nature such as Tai-Chi and Yoga (González-Valero et al., 2019).

In addition, it is also observed that the male gender shows a positive relationship between anxiety levels and the development of social self-concept. Very distant results were obtained by Jiotsa et al. (2021) where they state that the female gender is more likely to show higher levels of anxiety due to social pressure from the stereotypes of ideal bodies present in the different social networks, becoming a reason for discrimination for different social groups. However, the research carried out by Mahon and Hevey (2021) states that the male gender is also subject to this pressure due to the consumption of these stereotypes present in the different social networks, with most of these cases occurring in teenagers.

It is also observed that there are positive relationships for both sexes between motivation towards physical exercise and social self-concept. In this case, the male gender obtains higher scores for ego climate, whereas the female gender obtains higher scores for task climate. Similar results were obtained by Zurita-Ortega et al. (2016), where they state that males are more competitive than females. Likewise, the study by Shang and Yang (2021) states that when the practice of a sport is oriented towards ego climate, values such as greater social recognition play a fundamental role in its orientation. In addition, a higher level of anxiety is also observed for the male gender when they orientate the practice of physical activity towards the ego climate, where Zurita-Ortega et al. (2017a, b) state that when sport practice is oriented towards ego-climate, a higher level of anxiety is generated since defeat plays a negative role in this modality, where Ong (2019) also state that the male gender tends to be more competitive than the female people.

Considering all of the above, it should be noted that the current study shows the relationship between the motivation developed towards physical-sports practice, the control of anxiety and the incidence of these two areas on physical and social self-concept. For this reason, physical education classes should encourage a positive attitude towards the practice of physical activity, instruct students in techniques for channelling disruptive states and train students to respect and accept the different body images that each person possesses and that this should not be a method of exclusion for belonging to different social groups.

Limitations and Future Prospective

Furthermore, this research has several limitations, such as the very nature of the study, since being a descriptive and cross-sectional study, it has only been possible to analyse the variables at a single point in time. In addition, attention should also be paid to the sample, as they belong to a very specific geographical area and to a very specific branch of study, so that generalisations cannot be made. At the same time, this research was carried out during a period of high infection with the COVID-19 virus, which has had a negative impact on data collection, reducing the number of participants. Finally, it is important to highlight the presence of extraneous variables that may have affected the variables studied in this study.

Finally, with regard to future perspectives, focusing attention on the results obtained, the aim is to develop an intervention that has an impact on anxiety control, the motivation developed towards the practice of physical activity and on social and physical self-concept, where respect for each of the participants is encouraged.

Conclusions

In general, an acceptable value has been obtained for the different parameters of the general equation. This work shows that the development of a type of motivation towards physical-sports practice can play a fundamental role in the control of anxiety and in the development of physical and social self-concept. In this case, a positive relationship is observed between anxiety and the orientation of the practice of physical activity towards the ego-climate. Likewise, negative relationships are also observed between anxiety and the development of physical and social self-concept. Regarding these two areas of self-concept, higher scores are obtained when physical exercise is oriented towards the task climate instead of the ego climate.

Regarding gender, it is observed that the relationship between the ego climate and the task climate acquires a greater negative relationship for the female sex. With regard to the incidence of motivation on anxiety, it is observed that both obtain positive relationships towards ego climate, however, the male gender showed higher scores than the female. Likewise, in terms of the effects of anxiety on the development of social self-concept, a positive relationship with social self-concept is observed for the male gender, although this relationship is negative for the female. Finally, focusing attention on social self-concept and ego-climate, negative relationships are observed for males and positive ones for females.

Therefore, it can be affirmed that the motivation developed towards sport and the anxiety generated have a direct influence on the development of the social and physical self-concept, with gender playing a key role in the development of each of the variables.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Bardach, L., Oczlon, S., Pietschning, J., & Luftenegger, M. (2020). Has achievement goal theory been right? A meta-analysis of the relation between goal structures and personal achievement goals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(6), 1197–1220. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000419

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). AN Inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 893–897. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246.

Castro-Sánchez, M., Chacón-Cuberos, R., Ubago-Jiménez, J. L., Zafra-Santos, E., & Zurita-Ortega, F. (2018). An Explanatory model for the relationship between motivation in sport, victimization, and video game use in schoolchildren. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(9), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091866

Castro-Sánchez, M., Zurita-Ortega, F., Chacón-Cuberos, R., & Lozano-Sánchez, A.M. (2019). Motivational climate and levels of anxiety in soccer players of lower divisions. Retos: Nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación, (35), 164–169. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i35.63308

Chen, X. M., Huang, Y. F., Xiao, M. Y., Luo, Y. J., Liu, Y., Song, S. Q., Gao, X., & Chen, H. (2021). Self and the brain: Self-concept mediates the effect of resting-state brain activity and connectivity on self-esteem in school-aged children. Personality and Individuals Differences, 168, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110287

Claver, F., Martínez-Aranda, L. M., Conejero, M., & Gil-Arias, A. (2020). Motivation, discipline, and academic performance in physical education: A holistic approach from achievement goal and self-determination theories. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01808

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155.

Conde-Pipó, J., Melguizo-Ibáñez, E., Mariscal-Arcas, M., Zurita-Ortega, F., Ubago Jiménez, J. L., Ramírez-Granizo, I., & González-Valero, G. (2021). Physical self-concept changes in adults and older adults: Influence of emotional intelligence, intrinsic motivation and sports habits. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041711

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Dimas, M. A., Galway, S. C., & Gammage, K. L. (2021). Do you see what I see? The influence of self-objectification on appearance anxiety, intrinsic motivation, interoceptive awareness, and physical performance. Body Image, 39, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.05.010

Dolenc, P. (2019). Relationships between actual and perceived body weight, physical self-concept and anxiety among adolescent girls. Journal of Psychological and Educational Research, 27(1), 25–45.

Fernández-Bustos, J. G., González-Martí, I., Contreras, O., & Cuevas, R. (2015). Relación entre imagen corporal y autoconcepto físico en mujeres adolescentes. Revista Latinoamericana De Psicología, 47(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0120-0534(15)30003-0

Freitas, F. D., Queiroz-de Medeiros, A. C., & Lopes, F. D. (2021). Effects of social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and eating behavior-a longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645754

Gao, W. J., Ping, S. Q., & Liu, X. Q. (2020). Gender differences in depression, anxiety, and stress among collegue students: A longitudinal study from China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 292–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.121

García, F., & Musitu, G. (1999). AF-5: Autoconcepto Forma 5. TEA Ediciones.

González-Cutre, D., Sicilia, A., & Moreno, J. (2008). Modelo cognitivo-social de la motivación de logro en educación física. Psicothema, 20(4), 642–651.

González-Valero, G., Zurita-Ortega, F., & Martínez-Martínez, A. (2017). Motivational and physical activity outlook in students: a systematic review. ESHPA- Education, Sport Health and Physical Activity, 1(1), 41–58. http://hdl.handle.net/10481/48961

González-Valero, G., Zurita-Ortega, F., Ubago-Jiménez, J.L., &Puertas-Molero, P. (2019). Use of meditation and cognitive behavioral therapies for the treatment of stress, depression and anxiety in students. A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(22), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224394

Gustems-Carnicer, J., Calderón, C., & Calderón-Garrido, D. (2019). Stress, coping strategies and academic achievement in teacher education Students. European Journal of Teacher Education, 42(3), 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2019.1576629

Jiotsa, B., Naccache, B., Duval, M., Rocher, B., & Grall-Bronnec, M. (2021). Social media use and body image disorders: association between frequency of comparing one’s own physical appearance to that of people being followed on social media and body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062880

Kayani, S., Kiyani, T., Kayani, S., Morris, T., Biastutti, M., & Wang, J. (2021). Physical activity and anxiety of chinese university students: Mediation of self-system. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094468

Kozina, A. (2019). The development of multiple domains of self-concept in late childhood and in early adolescence. Current Psychology, 38(6), 1435–1442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9690-9

Lindell-Postigo, D., Zurita-Ortega, F., Ortiz-Franco, M., & González-Valero, G. (2020). Cross-sectional study of self-concept and gender in relation to physical activity and martial arts in Spanish adolescents during the COVID-19 lockdown. Education Sciences, 10(8), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10080210

Mahon, C., & Hevey, D. (2021). Processing body image on social media: Gender differences in adolescent boys’ and girls’ agency and active coping. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.626763

Marchena, C., Bernabéu, E., & Iglesias, T. (2020). Are adherence to the mediterranean diet, emotional eating, alcohol intake, and anxiety related in university students in Spain? Nutrients, 12(8), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082224

Martínez-Marín, M. D., Martínez, C., & Paterna, C. (2021). Gendered self-concept and gender as predictors of emotional intelligence: A comparison through of age. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02417-9

Mascret, N., Danthony, S., & François, C. (2019). Anxiety during tests and regulatory dimension of anxiety: A five-factor French version of the Revised Test Anxiety scale. Current Psychology, 40(11), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00481-w

McDonald, R. P., & Marsh, H. W. (1990). Choosing a multivariate model: Noncentrality and goodness of fit. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 247–255.

Merino-Fernández, M., Brito, C. J., Miarka, B., & Díaz-de-Durana, A. (2020). Anxiety and emotional intelligence: Comparisons between combat sports, gender and levels using the trait meta-mood scale and the inventory of situations and anxiety response. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00130

Newton, M., Duda, J.L., & Yin, Z. (2000). Examination of the psychometric properties of the Perceived Motivational Climate in Sport Questionnaire-2 in a sample of female athlethes. Journal of Sport Sciences, 18¸275–290.

Nicholls, J. G. (1989). The competitive ethos and democratic education. Harvard University Press.

Ong, N. C. H. (2019). Assessing objective achievement motivation in elite athletes: A comparison according to gender, sport type, and competitive level. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17(4), 397–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1349822

Orris, K., Cain, J., Mayol, M. H., Scott, B., Everett, K. L., & Beekley, M. D. (2020). Differences in social physique anxiety and sport motivation among collegiate athletes. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 47(5), 29–30. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000476476.79903.fb

Piccirllo, M. L., Lim, M. H., Fernández, K. A., Pasch, L. A., & Rodebaugh, T. L. (2021). Social anxiety disorder and social support behavior in friendships. Behavior Therapy, 52(3), 720–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2020.09.003

Putnick, D. L., Hahn, C. S., Hendricks, C., & Bornstein, M. H. (2020). Developmental stability of scholastic, social, athletic, and physical appearance self-concepts from preschool to early adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(1), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13107

Ramírez-Granizo, I. A., Sánchez-Zafra, M., Zurita-Ortega, F., Puertas-Molero, P., González-Valero, G., & Ubago-Jiménez, J. L. (2020). Multidimensional self-concept depending on levels of resilience and the motivational climate directed towards sport in schoolchildren. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020534

Ruffault, A., Bernier, M., Fournier, J., & Hauw, N. (2020). Anxiety and motivation to return to sport during the French COVID-19 lockdown. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.610882

Sanz, J., & Navarro, M. E. (2003). Propiedades psicométricas de una versión española del Inventario de Ansiedad de Beck (BAI) en estudiantes universitario. Ansiedad y Estrés, 9, 59–84.

Shang, Y., & Yang, S. Y. (2021). The effect of social support on athlete burnout in weightlifters: The mediation effect of mental toughness and sports motivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.649677

Shavelson, R. J., Hubner, J. J., & Stanton, G. C. (1976). Self-concept: Validation of construct interpretations. Review of Educational Research, 46(3), 407–441. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543046003407

Tenenbaum, G., & Eklund, R. C. (2007). Handbook of sport psychology. John Wiley & Sons.

Trigueros, R., Padilla, A.M., Aguilar-Parra, J.M., Rocamora, P., Morales-Gázquez, M.J., & López-Liria, R. (2020). The influence of emotional intelligence on resilience, test anxiety, academic stress and the mediterranean diet. A study with university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062071

Ubago-Jiménez, J. L., Zurita-Ortega, F., San Román-Mata, S., Puertas-Molero, P., & González-Valero, G. (2020). Impact of physical activity practice and adherence to the mediterranean diet in relation to multiple intelligences among university students. Nutrients, 12(9), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092630

Voulgaridou, I., & Kokkinos, C. M. (2020). The mediating role of friendship jealousy and anxiety in the association between parental attachment and adolescents’ relational aggression: A short-term longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 109, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104717

Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (1996) Fundamentos de psicología del deporte y del ejercicio físico. Ariel

Zurita-Ortega, F., Lindell-Postigo, D., González-Valero, G., Puertas-Molero, P., Ortiz-Franco, M., & Muros, J. J. (2021). Analysis of the psychometric properties of the five-factor self-concept questionnaire (AF-5) in Spanish students during the COVID-19 lockdown. Current Psychology, 40(5), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01856-8

Zurita-Ortega, F., Rodríguez-Fernández, S., Olmo-Extremera, M., Castro-Sánchez, M., Chacón-Cuberos, R., & Cepero-González, M. (2017a). Analysis of resilience, anxiety and sports injuries in soccer by competition level. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 12(35), 135–142.

Zurita-Ortega, F., Zafra-Santos, E. O., Valdivia-Moral, P., Rodríguez-Fernández, S., Castro-Sánchez, M., & Muros-Molina, J. J. (2017b). Analysis of resilience, self-concept and motivation in Judo as gender. Revista De Psicología Del Deporte, 26(1), 71–81.

Funding

Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Granada / CBUA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: E.M.I; F.Z.O; G.G.V; Methodology: E.M.I; J.L.U.J; C.J.L.G; Investigation: E.M.I; F.Z.O; G.G.V; J.L.U.J; C.J.L.G. Data Curation: E.M.I; F.Z.O; G.G.V; Writing/ Review: E.M.I; C.J.L.G; Supervision: F.Z.O

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors has a conflict of interest to declare, and all authors were involved in the study design, data collection and interpretation, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. This manuscript is not currently being considered for publication by another journal.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Melguizo-Ibáñez, E., Zurita-Ortega, F., Ubago-Jiménez, J.L. et al. An explanatory model of the relationships between sport motivation, anxiety and physical and social self-concept in educational sciences students. Curr Psychol 42, 15237–15247 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02778-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02778-9