Abstract

Parents of young children who exhibit behavioral problems often experience lower marital satisfaction. In the present study we aimed to explore the association between preschool children's noncompliant behavior and marital satisfaction, and to explain it through the mediating role of parental self-efficacy and satisfaction with parenting. Participants were 188 married Israeli couples with a typically developing child aged 3 to 6, selected in a convenience sample. Mothers and fathers independently completed measures of child’s behavior, marital satisfaction, parental self-efficacy, and satisfaction with parenting. Data were collected between September 2019 and February 2020 and were analyzed using the common fate model (CFM). Results indicate a direct, negative association between child's noncompliant behavior and marital satisfaction, which was fully explained by parental self-efficacy and satisfaction with parenting. The study suggests that both parents are affected by their young child’s noncompliance, with a spillover effect from the parent–child relationship into the marital relationship. The findings highlight the importance of early treatment of children's noncompliance and indicate that interventions aimed at enhancing parents’ self-efficacy and satisfaction, as well as the inclusion of both parents in treatment, may be beneficial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Young children's noncompliance toward parental requests is one of the most common behavioral problems, often the first to lead parents to seek professional intervention (Kalb & Loeber, 2003; McMahon & Forehand, 2005). Noncompliance in early childhood puts preschool-aged children at risk of experiencing difficulties in everyday situations (e.g., Ogundele, 2018), and increases the risk for a range of serious behavioral, cognitive, and emotional difficulties later in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (e.g., Burke & Loeber, 2017; D’Souza et al., 2020).

In addition to these possible negative outcomes for children, noncompliance in young children can adversely affect parents’ well-being and interparental relationship (Pettit & Arsiwalla, 2008), and indeed research has shown that parents of young children who exhibit behavioral problems often experience lower marital satisfaction (Mark & Pike, 2017).

Family systems theory (FST; Minuchin, 1974) provides a theoretical framework for understanding the impact of rearing children with behavioral problems on parents and on processes within the family. FST views the family as a functional unit composed of individual members and several subsystems, each of which cannot be fully understood outside the context of the specific family system and the interactions between its subsystems (Weeland et al., 2021). Thus, children’s behavioral problems should be assessed in the context of their interaction with other family subsystems, including their parents’ marital relationship. Building on the FST theoretical framework and previous empirical literature, which will be reviewed below, the present study sought to contribute to a broader understanding of the association between young children’s noncompliance and marital satisfaction, and its practical implications, by addressing the following four knowledge gaps.

First, FST assumes interdependency and mutual influence among family subsystems (Cox & Paley, 2003). However, despite strong theoretical grounds for a bi-directional influence between parents and children, and empirical evidence suggesting that children’s behavioral problems may impair their parents’ marital relationship, most previous studies have focused on the influence of marital relationship on children’s behavioral problems (e.g., McCoy et al., 2009; Vaez et al., 2015), while a relatively small number of studies has examined the impact of children’s behavioral problems on marital relationships and satisfaction (Baker et al., 2005; Ben-Naim et al., 2019). In the present study, we aimed at addressing this gap by focusing on the less explored direction of influence and examining the effect of children’s noncompliant behavior on marital satisfaction.

Second, considerable research regarding the association between children's behavioral problems and marital satisfaction has focused on parents of children diagnosed with behavioral disorders, developmental delays, or autism spectrum disorder (e.g., Robinson & Neece, 2015; Sim et al., 2017; Weyers et al., 2019). In the present study, we sought to add to the existing body of knowledge by focusing on a non-clinical sample of typically developing children, and examining the association between their mild behavioral problems and parents’ marital satisfaction.

Third, research has shown the negative association between children’s behavioral problems and marital satisfaction (e.g., Goldstein et al., 2007; Mark & Pike, 2017); however, the mechanism explaining this association has not been sufficiently examined. In the present study we aimed to examine the association between noncompliant behaviors of preschool children and marital satisfaction and to explain the impairment in marital satisfaction, through the mediating role of parental self-efficacy and satisfaction with parenting.

Fourth, FST holds that in order to fully understand processes and effects within the family system, data from both caregivers is required (Weeland et al., 2021). However, most existing research on children's behavioral problems in the family context has focused primarily on mothers, with much less focus being given to fathers (Cabrera et al., 2018). Nonetheless, in recent years there has been a noticeable increase in acknowledging the importance of adopting a family systems approach, by including both mothers and fathers in research (Steenhoff et al., 2019). In the present study, we aimed at addressing this gap and following previous research recommendations by obtaining data from both the mothers and fathers of each family system, assessing the intercorrelations and differences or similarities between mothers’ and fathers’ reports, and examining the study’s hypotheses at the dyadic level.

Children's Noncompliance and Marital Satisfaction

Noncompliance, characterized by children’s failure to follow specific parental requests or instructions within a certain time frame (Kalb & Loeber, 2003), is one of the most common behavioral problems in young children (McMahon & Forehand, 2005). The occasional opposition to parental control during early childhood is considered normative (Wakschlag et al., 2007); however, for some young children, such initially age-appropriate noncompliant behaviors persist and escalate into more frequent and severe behavioral problems, putting the child at risk for short- and long-term negative outcomes (Perle, 2019). Noncompliance in preschool-aged children has been associated with difficulties in everyday situations, including social relations with peers and family members (Ogundele, 2018), with poor academic performance (Gleason et al., 2016), and with a higher probability of expulsion from preschool (Gilliam & Reyes, 2018). Persistent noncompliance has been also associated with a number of psychiatric diagnoses and serious child difficulties later in life, including Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) (Burke & Loeber, 2017), Conduct Disorder (CD) (Keenan & Wakschlag, 2000), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Cantwell, 1996), internalizing disorders (Ezpeleta et al., 2017), and antisocial and delinquent behavior (Broidy et al., 2003).

Marital satisfaction refers to the overall subjective evaluation of the marital relationship by a specific individual (Bradbury et al., 2000), and to the subjective perception of the marriage's benefits and costs (Stone et al., 2008). Marital satisfaction is considered a broad and complex concept, associated with various aspects within and outside the romantic relationship and influenced by various factors including parenting and children’s social-emotional development and behavior (Bradbury et al., 2000; Vaez et al., 2015).

While parenting young children in itself involves an increased load of tasks, responsibilities, and concerns that can affect parents and their marital relationship (Perren et al., 2005), parenting a child who exhibits behavioral problems is particularly challenging, and indeed, previous research has reported low marital satisfaction among parents of young children with behavioral problems (Goldstein et al., 2007; Mark & Pike, 2017; Robinson & Neece, 2015; Vaez et al., 2015). Noncompliant young children typically exhibit repeated opposition to parental requests during daily routines, leading to frequent parent–child struggles. The cumulative impact of these daily challenges adversely affects parents’ relationships (Bush & Price, 2020; Crnic et al., 2005), and was found to predict increased levels of marital conflict and parental arguments about their child (Jenkins et al., 2005).

The association between children’s behavioral problems and marital satisfaction is also supported by couple therapy studies, which indicate that reducing parental conflict over child rearing results in improvements in marital satisfaction (Gattis et al., 2008; Tavassolie et al., 2016), and by studies on parent training interventions for treating child's behavioral problems, which have shown that in addition to the improvement in child's behavior, there were also improvements in marital relationship and satisfaction (Weber et al., 2019; Zemp et al., 2016).

Based on the aforementioned previous findings, we hypothesized that (H1) Higher levels of preschool children's noncompliant behavior will be associated with lower levels of marital satisfaction.

Potential Explanatory Mechanisms

Parental Self-Efficacy as a Mediator

Parental self-efficacy reflects the extent to which parents believe they can fulfill their parenting roles in a competent and effective manner (Jones & Prinz, 2005; Peacock-Chambers et al., 2017). Parental self‐efficacy is a key factor in the healthy functioning of parents and in the welfare of parents and their children, and has been associated with better adaptation to parenthood (Albanese et al., 2019; Biehle & Mickelson, 2011). Higher levels of parental self-efficacy have been associated with more positive parenting behaviors (Peacock-Chambers et al., 2017; Ponomartchouk & Bouchard, 2015), providing higher levels of reinforcement, praise, and affection toward the child, and with engagement in more leisure and child-focused activities with the child (Glatz & Buchanan, 2015; Peacock-Chambers et al., 2017; Ponomartchouk & Bouchard, 2015).

However, parenting a child with behavioral problems may impair parental self-efficacy. Research has repeatedly shown a negative association between children’s behavioral problems and parental self-efficacy (Glatz & Buchanan, 2015; Heerman et al., 2017), and this association was explained by the possible interpretation of parents that their children’s behavioral problems are a result of their parenting failures (Slagt et al., 2012; Van Eldik et al., 2017). Furthermore, parental self-efficacy has been correlated with marital satisfaction (Merrifield & Gamble, 2013; Solmeyer & Feinberg, 2011). In a study of 1430 mothers and 2029 fathers of children between the ages of two to six, parental self-efficacy was found to be a positive predictor of marital satisfaction, for both mothers and fathers (Kwan et al., 2015). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that (H2) The association between child's noncompliant behavior and marital satisfaction will be mediated by parental self-efficacy.

Satisfaction with Parenting as a Mediator

Satisfaction with parenting reflects the degree to which parents feel satisfied in their parental role (Jones & Prinz, 2005; Peacock-Chambers et al., 2017). It refers to the quality of the positive affect associated with the parental role, such as the parent's joy in being a parent and the parent's enjoyment of his or her relationship with the child (Johnston & Mash, 1989; Roger & Matthews, 2004). The positive association between satisfaction with parenting and marital satisfaction is substantial and well established in the literature (Hasson-Ohayon et al., 2019; Yoo, 2020). Higher levels of satisfaction with parenting are related to higher levels of marital satisfaction and to parents’ well-being and health (Yoo, 2020). In addition, low satisfaction with parenting was found to be associated with children's behavioral problems (Johnston & Mash, 1989; Ohan et al., 2000; Salari et al., 2014), dysfunctional parenting, and parents' harsh disciplinary practices (Roger & Matthews, 2004). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that (H3) The association between child's noncompliant behavior and marital satisfaction will be mediated by satisfaction with parenting.

In sum, previous studies have shown direct but separate associations between child’s behavior, marital satisfaction, parental self-efficacy, and satisfaction with parenting. However, to the best of our knowledge, the mediating role of parental self-efficacy and satisfaction with parenting in the association between child’s behavioral problems and marital satisfaction remains unexplored. The present study aimed to address this gap.

Method

Participants

Sample Size Considerations

Previous studies that utilized dyadic data analysis methods produced a broad range of sample sizes. The number of dyads was found to range from 25 to 411 dyads, with a median number of 101 dyads, and an estimated typical sample size of 80 dyads (Kenny et al., 2006). The question of the minimum number of dyads that can be considered a sufficient sample size was addressed by previous research. A simulation study that examined the effect of different sample sizes on the accuracy of the estimates and standard errors found that a sample size of 100 groups (e.g., couples) yields unbiased and accurate estimates and standard errors (Maas & Hox, 2005). Similarly, a sample size of at least 100 dyads was recommended for multi-level analysis (Fuchs et al., 2017). Du and Wang (2016) indicated that the minimum number of dyads needed for dyadic data analysis depends on the proportion of singletons (PS) in the study (meaning, proportion of cases in which one of the two dyad members fails to complete self-report measures). Their overall suggestion was to have a minimum of 50 dyads when there are no missing data (PS = 0%), and a minimum of 100 dyads when the missing data proportion is above 30% (Du & Wang, 2016). Based on the aforementioned previous findings and recommendations, we initially aimed at obtaining a sample of at least 100 couples. To further assess the sample size, we used the G*Power 3.1.9.7 program (Faul et al., 2007), with the following assumptions: type 1 error of 5%, desired power of 80%, and medium expected effect size of 0.3 between child’s noncompliant behavior (ODBTA subscale) and marital satisfaction (CSI-4) in two groups (i.e., fathers and mothers). This a priori power analysis calculation yielded a minimum sample size of 141 dyads (282 individuals, 141 fathers and 141 mothers). Accordingly, we aimed at sampling at least 141 couples.

The final sample consisted of 188 couples (a total of 376 individuals, 188 fathers and 188 mothers), with no missing data (proportion of singletons = 0%), which suggests sufficient power (0.80) for detecting a medium effect size.

Sample Characteristics

Each of the 188 couples in the sample had a preschool child in the age range of 3–6 years (M = 4.55, SD = 0.78). All families were Israelis and Jewish. All parents were married, and the average number of children per household was 2.52 (SD = 0.82). The mean age of the mothers was 36.1 years (SD = 4.2) and of the fathers 38.4 (SD = 4.5). The majority of parents had academic degrees (81.9% of the mothers and 64.4% of the fathers). Forty-one percent of the mothers and 52% of the fathers were private sector employees. Thirty-five percent of the mothers and 13% of the fathers were public sector employees, and 22% of the mothers and 25% of the fathers were self-employed or had a free profession. Two percent of the mothers were unemployed. A majority of the children in the sample were males (54.3%) and 45.7% were females. Most of the children (97.9%) were in kindergartens.

Measures

Child's noncompliant behavior was measured using the Oppositional Defiant Behavior Towards Adults (ODBTA) subscale of the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI; Eyberg & Pincus, 1999), the Burns and Patterson (2000) version (Burns & Patterson, 2000). ECBI is a parent-rating questionnaire, widely used to assess behavioral problems of children between the ages 2 to 16 in clinical and non-clinical samples. The Oppositional Defiant Behavior Towards Adults (ODBTA) subscale is a 10-item subscale that assesses the frequency in which children's noncompliant-oppositional-defiant behaviors occur on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Never; 7 = Always); higher scores indicate higher levels of child’s noncompliant behavior. Example items include "Refuses to do chores when asked" and "Does not obey house rules on own."

A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 and 0.90 was reported for boys and girls, respectively, for the original ODBTA subscale (Burns & Patterson, 2000), and was 0.95 for both the sample of fathers and the sample of mothers in the present study.

Marital satisfaction was measured using the Couple Satisfaction Index (CSI-4; Funk & Rogge, 2007), which is an abbreviated version of the CSI-32. The CSI-4 assesses individuals’ satisfaction with their marital relationship. The questionnaire consists of four items. The first item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = extremely unhappy; 6 = perfect), and the three other items are rated on a 6-point Likert scale (0 = not at all; 5 = completely); higher scores indicate higher levels of relationship satisfaction. Example items include: "I have a warm and comfortable relationship with my partner" and "How rewarding is your relationship with your partner?" A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.94 was reported for the original CSI-4 scale (Funk & Rogge, 2007), and was 0.95 for the sample of fathers and 0.96 for the sample of mothers in the present study.

Parental Self-Efficacy and Satisfaction with Parenting were measured using the Parenting Sense of Competence Scale (PSOC; Gibaud-Wallston & Wandersman, 1978), comprising two subscales. The first subscale, parental self-efficacy ('Efficacy'), assesses the parent's competence, problem-solving abilities, and capability in the parental role (e.g., "Being a parent is manageable, and any problems are easily solved", "If anyone can find the answer to what is troubling my child, I am the one"). The second subscale, parents' satisfaction with parenting ('Satisfaction'), assesses the parent's anxiety, frustration, and motivation in the parental role (e.g., "Even though being a parent could be rewarding, I am frustrated now while my child is at his/her present age" and "Being a parent makes me tense and anxious").

The PSOC consists of 17 items rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 6 = strongly agree). For the eight items of the efficacy subscale, high scores indicate high parental self-efficacy and competence; for the nine items of the satisfaction subscale, high scores indicate low satisfaction with parenting. In this study, for clarity and simplicity reasons, the respondents' reported values on the satisfaction subscale were reversed before analyzed, so that a high score on the questionnaire reflects high satisfaction with parenting and low scores reflect low satisfaction with parenting.

A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70 and 0.82 was reported for the original 'Efficacy' and 'Satisfaction' subscales, respectively (Gibaud-Wallston & Wandersman, 1978). In the present study, a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 and 0.90 was found for the 'Efficacy' subscale (parental self-efficacy), and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 and 0.87 was found for the 'Satisfaction' subscale (satisfaction with parenting), for the samples of fathers and mothers, respectively.

Procedure

Participants were recruited via social media through an invitation to parents of preschool children to participate in the research. Couples who showed an interest in participating, were married, and had a child in the age range of 3–6 years were scheduled for a face-to-face meeting with the first author or with a research assistant, for the purpose of completing the set of questionnaires. Prior to completing the set of questionnaires, parents signed a consent form according to which they agreed to complete the questionnaires on a voluntary basis without being reimbursed for their participation. Parents also completed a demographic questionnaire.

In dyadic data analysis, singletons, special type of missing data (i.e., data is available from only one member of a dyad), could occur and bias estimation (Du & Wang, 2016). In an attempt to avoid potential bias and obtain more reliable and valid estimates, participants in the present study were all couples who agreed to participate in the study together and to complete the study questionnaires separately. Couples in which one of the parents refused to complete the study questionnaires were excluded from the sample. This was resulted by having a final sample with no missing data (proportion of singletons = 0%), which protected against estimation biases and reduced power.

Couples completed the questionnaires during the face-to-face meeting, in the presence of the first author or her assistant. To ensure the confidentiality and privacy of each dyad member report, and for the purpose of avoiding mutual influence, couples were instructed to complete the questionnaires independently, without consulting each other. Couples who had more than one preschool child were asked to complete the set of questionnaires, thinking of the first-born child among them and referring to this child specifically in respect to all the study questionnaires, including the demographic questionnaire. Each parent completed a set of three questionnaires, according to the measures described above and in the above order. The protocol for this study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University.

Data Analysis

The data was carefully managed, with the hard-copy questionnaires being viewed and typed into Excel only by the researcher and an assistant, and then imported into an SPSS file for analysis. Data were analyzed using SPSS v. 25 and Amos 26.0 (Arbuckle, 2019).

Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients of internal consistency were calculated for each scale and subscale used in the study, separately for the samples of fathers and mothers. Descriptive statistics were produced using means and standard deviations for all variables. Correlations between variables were assessed using Pearson correlations. Differences between fathers and mothers were assessed using paired t-tests.

Nonindependence among distinguishable dyadic members (e.g., heterosexual couples) was measured with intra-dyadic correlations (correlations between fathers’ and mothers’ scores on the same variables) using Pearson correlations (Kenny et al., 2006), and data were determined to be non-independent. Ignoring nonindependence by using individuals as the unit of analysis and treating the data as if fathers and mothers were two samples can result in biased significance tests and loss of power (Kenny et al., 2006). Therefore, to avoid using a flawed strategy and potential biases, a dyadic analysis approach was chosen, and each dyad of father-mother was treated as a single unit of analysis.

The common fate model and the common fate mediation model were used to test our three hypotheses. A common fate model (CFM; Kenny et al., 2006) was used to assess the direct effects of child's noncompliant behavior on marital satisfaction, parental self-efficacy, and satisfaction with parenting, all at the dyadic level. Then, the CF mediation model (Ledermann & Macho, 2009) was used to assess the mediation effects at the dyadic level.

The use of the common fate model is appropriate when the variables measured in both partners can be conceived of as common dyadic constructs, and if the actor and partner effects observed in the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) are substantial and similar in size (Ledermann et al., 2010). In the CFM, the variables measured in both partners serve as pairwise indicators of the latent dyadic variables or constructs (Ledermann & Kenny, 2012). The CF mediation model allows a compact presentation and efficient evaluation of mediating effects in dyadic data, while accounting for measurement errors. The CFM models were computed using structural equation modeling (SEM). The model fit was assessed through the following indices: chi-squared, which is acceptable when the value is not significant; the goodness of fit index (GFI > 0.90); the comparative fit index (CFI > 0.90); the non-normed fit index (NNFI > 0.90); and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.06 to 0.08) (Arbuckle, 2019). To rule out the alternative explanations, according to which lower marital satisfaction leads to child’s noncompliant behavior through the mediation of parental self-efficacy or satisfaction with parenting, the reversed models were evaluated. The Expected Cross Validation Index (ECVI) was used for deciding between the hypothesized models and the reversed models, whereby the smallest ECVI estimate was considered to indicate a better fit (Kaplan, 2008). Structural equation modeling (SEM) was tested using AMOS software. Finally, we tested the indirect (mediating) effects for significance. In the present study, we used z-statistics and Sobel’s (1982) formula to estimate the standard error of the indirect effect. A post-hoc power analysis using G*Power 3.1.9.7 program (Faul et al., 2007) was conducted to examine whether the final sample of 188 couples had the statistical power to detect the effects sizes that were found for the two mediation models in the present study.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Analyses of Correlations

Table 1 presents means, SDs, and paired samples t-tests for each of the study variables.

As presented in Table 1, mothers reported higher levels of child's noncompliant behaviors and lower marital satisfaction compared to fathers, and fathers reported higher satisfaction with parenting in comparison to mothers.

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations between the study variables. As shown in Table 2, a strong negative correlation was found between child's noncompliant behaviors and parents' satisfaction with parenting (fathers: r = -0.68, p < 0.01; mothers: r = -0.72, p < 0.01) and between child's noncompliant behaviors and parental self-efficacy (fathers: r = -0.69, p < 0.01; mothers: r = -0.67, p < 0.01). In addition, a negative correlation was found between child's noncompliant behaviors and marital satisfaction (fathers: r = -0.48, p < 0.01; mothers: r = -0.46, p < 0.01). A positive correlation was found between marital satisfaction and satisfaction with parenting (fathers: r = 0.47, p < 0.01; mothers: r = 0.49, p < 0.01), and between marital satisfaction and parental self-efficacy (fathers: r = 0.52, p < 0.01; mothers: r = 0.60, p < 0.01). Finally, correlations between fathers and mothers were high for all study variables (0.67 < r < 0.83), which suggested that a CFM approach is more appropriate than an actor-partner interdependence model (APIM) alternative approach (Kenny et al., 2006; Ledermann et al., 2010).

Testing the Common Fate Models

The Common Fate Model of Direct Association Between Child's Noncompliant Behavior and Marital Satisfaction

We examined a CFM model in which child's noncompliant behavior directly predicted low marital satisfaction. This model provided a good fit (χ2(2) = 4.27; p = 0.12; GFI = 0.98; AGFI = 0.87; NFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.08).

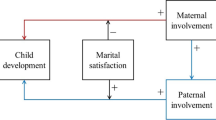

The results of this model showed that higher levels of child's noncompliant behaviors are associated with lower levels of marital satisfaction, β = -0.53, p < 0.001, which explained 29% of the variance in marital satisfaction (Fig. 1).

The Common Fate Mediation Model of Child's Noncompliant Behavior and Marital Satisfaction, With Parental Self-Efficacy as Mediator

We examined a CFM model in which child's noncompliant behavior predicted low marital satisfaction through the mediation of parental self-efficacy. This model provided a good fit (χ2(5) = 8.11; p = 0.15; GFI = 0.97; AGFI = 0.87; NFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.08). The results of this model showed that higher levels of child's noncompliant behaviors are associated with lower levels of parental self-efficacy (β = -0.83, p < 0.001). In addition, parental self-efficacy is positively associated with marital satisfaction (β = 0.43, p < 0.001). No significant direct association was found between child's noncompliant behavior and marital satisfaction (β = -0.26, p = 0.21).

The model explained 44% of the variance in marital satisfaction, with a total standardized effect of -0.62 (of child's noncompliant behavior on marital satisfaction), split into a direct standardized effect of -0.26 and an indirect standardized effect through parental self-efficacy of -0.35. To conclude, parental self-efficacy was found to fully mediate the relationship between child's noncompliant behavior and marital satisfaction (β = -0.35, p < 0.001). A post-hoc power analysis revealed that the final sample of 188 couples had a statistical power of 0.957 to detect the effect reported for this mediation model (Fig. 2).

Common Fate Mediation Model of Marital Satisfaction and Child's Noncompliant Behavior, With “Satisfaction With Parenting” as Mediator

We examined a CFM model in which child's noncompliant behavior predicted low marital satisfaction through the mediation of parents' satisfaction with parenting.

This model provided a good fit (χ2(3) = 3.37; p = 0.33; GFI = 0.98; AGFI = 0.92; NFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.04). The results of this model showed that higher levels of child's noncompliant behaviors are associated with lower levels of satisfaction with parenting (β = -0.88, p < 0.001). In addition, satisfaction with parenting is positively associated with marital satisfaction (β = 0.46, p < 0.001). No significant direct association was found between child's noncompliant behavior and marital satisfaction (β = -0.22, p = 0.53).

The model explained 43% of the variance in marital satisfaction, with a total standardized effect of -0.62 (of child's noncompliant behavior on marital satisfaction), split into a direct standardized effect of -0.22 and an indirect standardized effect through satisfaction with parenting of -0.40. To conclude, satisfaction with parenting was found to fully mediate the relationship between child's noncompliant behavior and marital satisfaction (β = -0.40, p < 0.001). A post-hoc power analysis revealed that the final sample of 188 couples had a statistical power of 0.986 to detect the effect reported for this mediation model (Fig. 3).

Additional Analyses: Reverse Models

To rule out the alternative explanation, according to which lower marital satisfaction leads to low parental self-efficacy, which in turn leads to child's noncompliant behavior, a reverse model was examined. The reversed model showed lower fit indices (χ2 (5) = 15.93, p = .007, GFI = .97; AGFI = .88, NFI = .98; CFI =.98, RMSEA = 0.11). Determining between the two models showed a lower ECVI for the hypothesized (original) model (ECVI = 0.19) compared to the alternative reverse model (ECVI = 0.26), indicating that the hypothesized associations between the variables have a better fit to the dataset. To exclude the alternative explanation, according to which lower marital satisfaction leads to low satisfaction with parenting, which in turn leads to child's noncompliant behavior, this second reverse model was also examined. The reversed model showed lower fit indices (χ2 (5) = 12.67, p = .027, GFI = .98; AGFI = .91, NFI = .98; CFI =.99, RMSEA = 0.09). Determining between these competing models showed a lower ECVI for the hypothesized (original) model (ECVI = 0.22) compared to the alternative model (ECVI = 0.24), indicating that the hypothesized associations between the variables have a better fit to the dataset.

Discussion

The aims of the present study were to investigate the relationship between preschool children's noncompliant behavior and marital satisfaction, while explaining this association through the mediating role of parental self-efficacy and satisfaction with parenting, using dyadic data analysis (CFMs). Our results indicate a direct, negative association between the level of child’s noncompliant behavior and marital satisfaction, with child’s noncompliant behavior being a predictor that explains a high amount of the variance in marital satisfaction. These results confirm our first hypothesis and support previous research concerning lower marital satisfaction among parents of children who exhibit behavioral problems (Robinson & Neece, 2015; Sears et al., 2016).

The family system approach perceives the family unit as consisting of a group of interdependent individuals and several subsystems, such as marital, parental, and child subsystems, whereby changes in one family member or in one subsystem influence the other family members and subsystems (Anderson et al., 2013). Research has consistently demonstrated the interdependency between family subsystems, while emphasizing the link between the parent–child relationship and the marital relationship. One of the most well-supported explanations for the relationship between these two subsystems is the "spillover hypothesis" (Sherrill et al., 2017; Zemp et al., 2018), according to which a stressful experience in one family subsystem is likely to spill over into another subsystem and affect the experience or behavior of the individual in a different context (Sherrill et al., 2017).

Most previous studies have shown spillover effects from the marital relationship to the parent–child relationship. Such studies have indicated that stress arising from marital conflicts spills over into the parent–child relationship, adversely affecting its quality and compromising parenting practices, which further leads to child behavioral problems (Buehler & Gerard, 2002; Coln et al., 2013; Sherrill et al., 2017; Warmuth et al., 2020). Fewer studies have examined the opposite direction of influence, in which children’s behavioral problems increase parent–child conflicts and stress, which spills over into the marital relationship, creating negativity and marital dissatisfaction. The few studies that did focus on this direction found spillover effects among children diagnosed with behavioral disorders (Ben-Naim et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2017; Weyers et al., 2019), autism spectrum disorder (Sim et al., 2017), and developmental delays (Robinson & Neece, 2015). Our results add to the existing literature in two respects: First, by supporting the existence of a spillover process from the parent–child subsystem to the marital subsystem, which is a less researched direction of influence, and second, by focusing on a population that is not commonly studied and demonstrating this effect among non-referred, typically developing preschool children who exhibit mild behavioral problems at a non-clinical level.

Noncompliance in preschool-aged children tends to be persistent and frequent, especially during daily routines, thus challenging the parent–child relationship by causing parents to repeatedly struggle with their child’s failure to comply. The frequent nature of these demanding and energy-consuming situations has a cumulative effect on parents and may influence them and the parent–child relationship in an undesired manner over time (Bush & Price, 2020; Mazur, 2006). Even when not severe, children's persistent noncompliant behaviors are likely to be perceived by parents as stressors, and as such may spill over into their marital relationship and become internal stressors, thus impairing marital satisfaction.

Furthermore, we examined how noncompliant behavior of typically developing preschool children is related to marital satisfaction through the mediated pathway of parental self-efficacy. This second hypothesis regarding the mediating role of parental self-efficacy was based on past research, which has repeatedly but separately shown parental self-efficacy to be negatively associated with child's behavioral problems (Glatz & Buchanan, 2015; Heerman et al., 2017; Salari et al., 2014), and positively associated with marital satisfaction (Kwan et al., 2015; Merrifield & Gamble, 2013; Solmeyer & Feinberg, 2011). The results supported our second hypothesis, indicating that the relationship between the noncompliant behavior of typically developing preschool children and marital satisfaction is fully mediated by parental self-efficacy, explaining a higher amount of the variance of marital satisfaction.

We focused on analyzing child-driven effects, according to which parental self-efficacy is affected by parents' interactions with their child and by child behavior. Successful parent–child interactions and positive child behaviors strengthen parental self-efficacy, while situations of failure and child's inappropriate behaviors weakens parental self-efficacy (Glatz & Buchanan, 2015). Our results are in line with the previous literature that suggests that parenting a child with behavioral problems may impair parental self-efficacy, as parents may interpret their child's inappropriate behavior as their own failure at parenting (Slagt et al., 2012; Van Eldik et al., 2017). Indeed, in case of a noncompliant child, parents are usually compelled to handle daily situations in which the child ignores or actively refuses their instructions. Parents' failure to obtain their child’s compliance, together with the fact that there are usually several frustrating struggles a day, can certainly endanger the parents’ perception of their ability to fulfill their parental role effectively and to influence their child in a desirable manner.

Moreover, we examined how the noncompliant behavior of typically developing preschool children is related to marital satisfaction through the mediated pathway of satisfaction with parenting. We based this third hypothesis regarding the mediating role of satisfaction with parenting on past research, which has found satisfaction with parenting to be negatively related to child's behavioral problems (Johnston & Mash, 1989; Ohan et al., 2000) and positively related to marital satisfaction (Hasson-Ohayon et al., 2019; Yoo, 2020). The results supported our third hypothesis, indicating that the relationship between the noncompliant behavior of typically developing preschool children and marital satisfaction is fully mediated by satisfaction with parenting.

As with the previous mediation model, the results may suggest that the low level of marital satisfaction among parents of children with behavioral problems actually points to a complex process in which engaging with a noncompliant child on a daily basis impairs parents' perception of satisfaction with their parenting, leading in turn to lesser marital satisfaction. This complex process is in line with the spillover hypothesis, suggesting that child's persistent noncompliance toward the parents leads to a decrease in parental satisfaction with parenting, and that the negativity aroused in the parent–child subsystem spills over into the marital relationship subsystem, resulting in low marital satisfaction.

Given that most previous research on the associations between children's behavioral problems and parental constructs relied primarily on mothers (Cabrera et al., 2018), the results of the present study contribute to the existing body of research by providing a deeper understanding of processes within the family system, as reflected in both parents’ perceptions.The positive and strong correlations between mothers’ and fathers' reports on children's noncompliance and their parenting perceptions reveal nonindependence between parents, and indicate that these variables represent common dyadic constructs (Ledermann & Kenny, 2012). The results indicate that noncompliance can be seen as a shared event that is external to the interparental relationship and influences both parents (Galovan et al., 2017). Parents share the family circumstances of having a noncompliant child and the frequent parent–child struggles involved. As a result, parents' perceptions of self-efficacy, as well as their parenting satisfaction, are impaired, leading to a shared experience of marital dissatisfaction.

In summary, the current study contributes to the literature in several important ways. First, by indicating child effects with a non-clinical sample of preschool-aged children exhibiting mild behavioral problems. Second, by suggesting that mothers and fathers are similarly affected by their young children’s noncompliance. Third, by showing a spillover effect from the parent–child relationship into the marital relationship, and fourth, by revealing the mechanism explaining the relationship between young children's noncompliance and marital satisfaction.

Clinical Implications

The present study results point to several clinical implications worth discussing.

Research indicates that although noncompliance in early childhood sometimes represents a transient problem, persistent noncompliance at this stage puts children at risk for a range of short- and long-term difficulties (e.g., Burke & Loeber, 2017; Ogundele, 2018). Our finding that parents of young children who exhibit mild noncompliance experience impairment in their parenting and marital relationship suggests that although behavioral problems can be a normal developmental phase for many young children, such problems may represent a significant disturbance to parents.

Taken together, these indications of the possible negative impact of noncompliance on children and their parents suggest that "small problems" should not be ignored. We believe that adopting a "wait and see" approach in the hope that children will outgrow their behavioral problems and that parents will successfully overcome the related difficulties they experience is not recommended. Ignoring small problems may mean a lost opportunity for preventing behavioral problems from escalating and for reducing the detrimental effect on parents’ marital relationship and parenting experiences. We argue that treating young children's noncompliant behaviors, even when not meeting the criteria for a clinical diagnosis, is important. Such an approach has a high potential of being successful in reducing the frequency and intensity of noncompliant behaviors, thereby lessening the burden placed on the parents and preventing parent–child tensions from spilling over into the marital relationship and impairing marital satisfaction. In addition, the literature suggests that the younger the child and the less intense the behavioral problems, the more effective the treatment (McMahon & Forehand, 2005). Also, the treatment of such problems requires a shorter and less intensive intervention (Perle, 2019). One such suitable intervention is parent management training (PMT), which is an effective treatment strategy for treating preschool-aged children’s behavioral problems (Leijten et al., 2019) that also shows positive outcomes for parents, including higher marital satisfaction (Zemp et al., 2016).

The findings of the present study regarding the mechanism explaining the association between children's noncompliance and marital satisfaction point to another important direction for intervention: addressing parental self-efficacy and satisfaction. Increasing parents' self-efficacy and satisfaction with parenting may have two main contributions. First, as the findings imply, it may prevent pressure on the marital relationship, thus reducing the impairment in marital satisfaction. Second, given that negative and dysfunctional parenting has a significant influence on the development and maintenance of young children’s behavioral problems (Smith et al., 2014; Yan et al., 2021) and given that self-efficacious and satisfied parents are more likely to engage in positive parenting behaviors and less likely to engage in negative parenting (De Haan et al., 2009; Peacock-Chambers et al., 2017), increasing parents' self-efficacy and satisfaction with parenting may lead to a decreased use of negative parenting practices, which may prevent additional behavioral problems.

As our findings suggest, mothers and fathers are both influenced by their child’s behavior, and the difficulties related to their parenting impact the marital relationship; therefore, including both parents in treatment is critical. In fact, interventions in which both parents are involved tend to result in better child and parent outcomes (Carr, 2019; Lundahl et al., 2008) and to increase parental consistency at home (Bagner & Eyberg, 2007. Therapists who work with both parents can help them understand how they differ from each other in their parenting behaviors and guide them in uniting around similar parenting strategies that will increase consistency with their child. Given that inconsistencies in parenting practices were found to predict children’s behavioral problems (Jenkins et al., 2005), such collaborative parenting could lead to better child outcomes, which in turn may protect against marital conflicts. Parents collaboration in parenting can also lead to less arguments and disagreements between them over disciplinary practices and the proper way to respond to their child's behavioral problems, thus reducing the frequency of interparental conflicts that might affect the marital relationship. This is supported by previous studies that indicated improvements in marital satisfaction as a result of reducing parental conflict over child rearing (e.g., Tavassolie et al., 2016).

Limitations

Several limitations are important to consider when interpreting the present study findings. First, the cross-sectional design of the study, in which all variables were simultaneously assessed, does not allow us to determine the cause-effect relationship. Future research should use longitudinal designs to verify causal pathways. Second, our study was based on parents' self-reported data, with no direct observation of children's behavior. Thus, ratings of children’s noncompliant behavior reflect parents’ perceptions. Future research may increase the reliability of the findings by obtaining additional data on child noncompliant behavior from independent sources such as direct observations of parent–child interactions in the context of daily routines in which parents provide the child with instructions, and child's compliance is measured. Moreover, parents' self-reported data regarding their marital satisfaction, their parental self-efficacy, and satisfaction with parenting may also be affected by various biases, such as parents' reluctance to reveal private details of their romantic relationship, parents' difficulty in revealing feelings of frustration or failure in their parenting, and social desirability. Third, the present study examined the relationship between child's noncompliance and marital satisfaction through the mediated pathway of parental self-efficacy and satisfaction with parenting. Future research on this relationship should address additional variables related to parenting and couple's relationships that can influence marital satisfaction and can be influenced by it. Such variables can be parental stress, parenting practices, parent–child relationship, and social support. Fourth, the sample chosen for the present study is of married biological parents, cohabiting and sharing childrearing responsibilities, which limits the generalizability of the results to other, more at-risk populations. However, the main aim of the present study was not to generalize the findings to diverse populations, but rather to specifically focus on functioning families, and to examine associations between young children’s mild behavioral problems and parents with no marital discord. Therefore, results may still be valid for such populations.

Conclusion

The present study focused on a less researched direction of influence and sheds new light on the impact of child's noncompliance on parents' marital satisfaction and on the mechanisms explaining this relationship. The results of the current study indicate the possibility that intervention programs aimed at reducing noncompliant behaviors of preschool children may be effective in increasing marital satisfaction and can usefully include a focus on enhancing parental self-efficacy and improving parents' perceptions of their parenting. This could offer an important direction for future research and clinical practice, which may focus on breaking the vicious circle of child's behavioral problems and deterioration in the marital relationship.

References

Albanese, A., Russo, G., & Geller, P. (2019). The role of parental self-efficacy in parent and child well-being: A systematic review of associated outcomes. Child Care, Health and Development, 45(3), 333–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12661

Anderson S.A., Sabatelli R.M., Kosutic I. (2013). Systemic and ecological qualities of families. In: Peterson G., Bush K. (eds) Handbook of Marriage and the Family. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3987-5_6

Arbuckle, J. L. (2019). Amos (Version 26.0). [Computer Program]. Chicago: IBM SPSS.

Bagner, D. M., & Eyberg, S. M. (2007). Parent–child interaction therapy for disruptive behavior in children with mental retardation: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36(3), 418–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410701448448

Baker, B. L., Blacher, J., & Olsson, M. B. (2005). Preschool children with and without developmental delay: Behaviour problems, parents’ optimism and well-being. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49(8), 575–590. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00691.x

Ben-Naim, S., Gill, N., Laslo-Roth, R., & Einav, M. (2019). Parental stress and parental self-efficacy as mediators of the association between children’s ADHD and marital satisfaction. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(5), 506–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054718784659

Biehle, S., & Mickelson, K. (2011). Personal and co-parent predictors of parenting efficacy across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(9), 985–1010. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2011.30.9.985

Bradbury, T. N., Fincham, F. D., & Beach, S. R. H. (2000). Research on the nature and determinants of marital satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 964–980. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00964.x

Broidy, L. M., Nagin, D. S., Tremblay, R. E., Bates, J. E., Brame, B., Dodge, K. A., … & Vitaro, F. (2003). Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: A six-site, cross-national study. Developmental Psychology, 39(2), 222-245. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.222

Buehler, C., & Gerard, J. M. (2002). Marital conflict, ineffective parenting, and children’s and adolescents’ maladjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(1), 78–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00078.x

Burke, J. D., & Loeber, R. (2017). Evidence-based interventions for oppositional defiant disorder in children and adolescents. In L. A. Theodore (Ed.), Handbook of Evidence-Based Interventions for Children and Adolescents (pp. 181–191). Springer Publishing Company.

Burns, G. L., & Patterson, D. R. (2000). Factor structure of the eyberg child behavior inventory: A parent rating scale of oppositional defiant behavior toward adults, inattentive behavior, and conduct problem behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29(4), 569–577. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP2904_9

Bush, K. R., & Price, C. A. (2020). Families & change: Coping with stressful events and transitions. SAGE Publications.

Cabrera, N. J., Volling, B. L., & Barr, R. (2018). Fathers are parents, too! widening the lens on parenting for children’s development. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 152–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12275

Cantwell, D. P. (1996). Classification of child and adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01377.x

Carr, A. (2019). Family therapy and systemic interventions for child-focused problems: The current evidence base. Journal of Family Therapy, 41(2), 153–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12226

Coln, K. L., Jordan, S. S., & Mercer, S. H. (2013). A unified model exploring parenting practices as mediators of marital conflict and children’s adjustment. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 44(3), 419–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-012-0336-8

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01259

Crnic, K. A., Gaze, C., & Hoffman, C. (2005). Cumulative parenting stress across the preschool period: Relations to maternal parenting and child behaviour at age 5. Infant and Child Development, 14(2), 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.384

D’Souza, S., Underwood, L., Peterson, E. R., Morton, S. M., & Waldie, K. E. (2020). The association between persistence and change in early childhood behavioural problems and preschool cognitive outcomes. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 51, 416–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-019-00953-x

De Haan, A. D., Prinzie, P., & Deković, M. (2009). Mothers’ and fathers’ personality and parenting: The mediating role of sense of competence. Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1695–1707. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016121

Du, H., & Wang, L. (2016). The impact of the number of dyads on estimation of dyadic data analysis using multilevel modeling. Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 12(1), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000105.

Eyberg, S. M., & Pincus, D. (1999). Eyberg child behavior inventory and sutter-eyberg student behavior inventory-revised: Professional manual. Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Ezpeleta, L., Granero, R., de la Osa, N., & Domènech, J. M. (2017). Developmental trajectories of callous-unemotional traits, anxiety and oppositionality in 3–7 year-old children in the general population. Personality and Individual Differences, 111, 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.005

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Fuchs, P., Nussbeck, F. W., Meuwly, N., & Bodenmann, G. (2017). Analyzing dyadic sequence data—research questions and implied statistical models. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 429. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00429

Funk, J. L., & Rogge, R. D. (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 572–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572

Galovan, A. M., Holmes, E. K., & Proulx, C. M. (2017). Theoretical and methodological issues in relationship research: Considering the common fate model. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 34(1), 44–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407515621179

Gattis, K. S., Simpson, L. E., & Christensen, A. (2008). What about the kids? Parenting and child adjustment in the context of couple therapy. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(6), 833–842. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013713

Gibaud-Wallston, J., & Wandersmann, L. P. (1978). Development and utility of the parenting sense of competence scale. John F. Kennedy center for research on education and human development.

Gilliam, W. S., & Reyes, C. R. (2018). Teacher decision factors that lead to preschool expulsion. Infants & Young Children, 31(2), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0000000000000113

Glatz, T., & Buchanan, C. M. (2015). Over-time associations among parental self-efficacy, promotive parenting practices, and adolescents’ externalizing behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(3), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000076

Gleason, M. M., Goldson, E., & Yogman, M. W. (2016). Addressing early childhood emotional and behavioral problems. Pediatrics, 138(6), e20163025. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3025

Goldstein, L. H., Harvey, E. A., Friedman-Weieneth, J. L., Pierce, C., Tellert, A., & Sippel, J. C. (2007). Examining subtypes of behavior problems among 3-year-old children, part II: Investigating differences in parent psychopathology, couple conflict, and other family stressors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35(1), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-006-9088-x

Hasson-Ohayon, I., Ben-Pazi, A., Silberg, T., Pijnenborg, G. H. M., & Goldzweig, G. (2019). The mediating role of parental satisfaction between marital satisfaction and perceived family burden among parents of children with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Research, 271, 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.037

Heerman, W., Taylor, J., Wallston, K., & Barkin, S. (2017). Parenting self-efficacy, parent depression, and healthy childhood behaviors in a low-income minority population: A cross-sectional analysis. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(5), 1156–1165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2214-7

Jenkins, J., Simpson, A., Dunn, J., Rasbash, J., & O’Connor, T. G. (2005). Mutual influence of marital conflict and children’s behavior problems: Shared and nonshared family risks. Child Development, 76(1), 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00827.x

Johnston, C., & Mash, E. J. (1989). A measure of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 18(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp1802_8

Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(3), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004

Kalb, L. M., & Loeber, R. (2003). Child disobedience and noncompliance: A review. Pediatrics, 111(3), 641–652. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.3.641

Kaplan, D. (2008). Structural equation modeling: Foundations and extensions (Vol. 10). Sage Publications.

Keenan, K., & Wakschlag, L. (2000). More than the terrible twos: The nature and severity of behavior problems in clinic-referred preschool children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology; an Official Publication of the International Society for Research in Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 28(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005118000977

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis Guilford press.

Kwan, R., Kwok, S., & Ling, C. (2015). The moderating roles of parenting self-efficacy and co-parenting alliance on marital satisfaction among chinese fathers and mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(12), 3506–3515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0152-4

Ledermann, T., & Kenny, D. A. (2012). The common fate model for dyadic data: Variations of a theoretically important but underutilized model. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(1), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026624

Ledermann, T., & Macho, S. (2009). Mediation in dyadic data at the level of the dyads: A structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(5), 661–670. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016197

Ledermann, T., Bodenmann, G., Rudaz, M., & Bradbury, T. N. (2010). Stress, communication, and marital quality in couples. Family Relations, 59(2), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00595.x

Leijten, P., Gardner, F., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Van Aar, J., Hutchings, J., Schulz, S., & Overbeek, G. (2019). Meta-analyses: Key parenting program components for disruptive child behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(2), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.900

Lin, X., Zhang, Y., Chi, P., Ding, W., Heath, M. A., Fang, X., & Xu, S. (2017). The mutual effect of marital quality and parenting stress on child and parent depressive symptoms in families of children with oppositional defiant disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1810. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01810

Lundahl, B. W., Tollefson, D., Risser, H., & Lovejoy, M. C. (2008). A meta-analysis of father involvement in parent training. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507309828

Maas, C. J. M., & Hox, J. J. (2005). Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 1(3), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241.1.3.86

Mark, K. M., & Pike, A. (2017). Links between marital quality, the mother–child relationship and child behavior: A multi-level modeling approach. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(2), 285–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416635281

Mazur, E. (2006). Biased appraisals of parenting daily hassles among mothers of young children: Predictors of parenting adjustment. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 30(2), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9031-z

McCoy, K., Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. T. (2009). Constructive and destructive marital conflict, emotional security and children’s prosocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(3), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01945.x

McMahon, R. J., & Forehand, R. L. (2005). Helping the noncompliant child: Family-based treatment for oppositional behavior (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Merrifield, K. A., & Gamble, W. C. (2013). Associations among marital qualities, supportive and undermining coparenting, and parenting self-efficacy: Testing spillover and stress-buffering processes. Journal of Family Issues, 34(4), 510–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X12445561

Minuchin, S. (1974). Families & family therapy. Harvard U. Press.

Ogundele, M. O. (2018). Behavioural and emotional disorders in childhood: A brief overview for paediatricians. World Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, 7(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v7.i1.9

Ohan, J. L., Leung, D. W., & Johnston, C. (2000). The parenting sense of competence scale: Evidence of a stable factor structure and validity. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 32(4), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087122

Peacock-Chambers, E., Martin, J. T., Necastro, K. A., Cabral, H. J., & Bair-Merritt, M. (2017). The influence of parental self-efficacy and perceived control on the home learning environment of young children. Academic Pediatrics, 17(2), 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.10.010

Perle, J. G. (2019). Rethinking ‘wait and see’ philosophies for childhood disruptive behaviour: A guide for pediatric medical providers. Early Child Development and Care, 189(13), 2085–2098. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1438424

Perren, S., Wyl, A., Bürgin, D., Simoni, H., & Klitzing, K. (2005). Intergenerational transmission of marital quality across the transition to parenthood. Family Process, 44(4), 441–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2005.00071.x

Pettit, G. S., & Arsiwalla, D. D. (2008). Commentary on special section on “bidirectional parent–child relationships”: The continuing evolution of dynamic, transactional models of parenting and youth behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(5), 711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9242-8

Ponomartchouk, D., & Bouchard, G. (2015). New mothers’ sense of competence: Predictors and outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(7), 1977–1986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9997-1

Robinson, M., & Neece, C. L. (2015). Marital satisfaction, parental stress, and child behavior problems among parents of young children with developmental delays. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 8(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2014.994247

Rogers, H., & Matthews, J. (2004). The parenting sense of competence scale: Investigation of the factor structure, reliability, and validity for an australian sample. Australian Psychologist, 39(1), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060410001660380

Salari, R., Wells, M. B., & Sarkadi, A. (2014). Child behaviour problems, parenting behaviours and parental adjustment in mothers and fathers in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 42(7), 547–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494814541595

Sears, M. S., Repetti, R. L., Reynolds, B. M., Robles, T. F., & Krull, J. L. (2016). Spillover in the home: The effects of family conflict on parents’ behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(1), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12265

Sherrill, R. B., Lochman, J. E., DeCoster, J., & Stromeyer, S. L. (2017). Spillover between interparental conflict and parent–child conflict within and across days. Journal of Family Psychology, 31(7), 900–909. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000332

Sim, A., Cordier, R., Vaz, S., & Falkmer, T. (2017). Relationship satisfaction and dyadic coping in couples with a child with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(11), 3562–3573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3275-1

Slagt, M., Deković, M., De Haan, A. D., Den Akker, V., Alithe, L., & Prinzie, P. (2012). Longitudinal associations between mothers’ and fathers’ sense of competence and children’s externalizing problems: The mediating role of parenting. Developmental Psychology, 48(6), 1554–1562. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027719

Smith, J. D., Dishion, T. J., Shaw, D. S., Wilson, M. N., Winter, C. C., & Patterson, G. R. (2014). Coercive family process and early-onset conduct problems from age 2 to school entry. Development and psychopathology, 26(4pt1), 917–932. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414000169

Solmeyer, A. R., & Feinberg, M. E. (2011). Mother and father adjustment during early parenthood: The roles of infant temperament and coparenting relationship quality. Infant Behavior and Development, 34(4), 504–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.07.006

Steenhoff, T., Tharner, A., & Væver, M. S. (2019). Mothers’ and fathers’ observed interaction with preschoolers: Similarities and differences in parenting behavior in a well-resourced sample. PLoS ONE, 14(8), e0221661. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221661

Stone, E. A., Shackelford, T. K., & Buss, D. M. (2008). Socioeconomic development and shifts in mate preferences. Evolutionary Psychology, 6(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/147470490800600309

Tavassolie, T., Dudding, S., Madigan, A. L., Thorvardarson, E., & Winsler, A. (2016). Differences in perceived parenting style between mothers and fathers: Implications for child outcomes and marital conflict. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(6), 2055–2068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0376-y

Vaez, E., Indran, R., Abdollahi, A., Juhari, R., & Mansor, M. (2015). How marital relations affect child behavior: Review of recent research. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 10(4), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2015.1112454

Van Eldik, W. M., Prinzie, P., Deković, M., & De Haan, A. D. (2017). Longitudinal associations between marital stress and externalizing behavior: Does parental sense of competence mediate processes? Journal of Family Psychology, 31(4), 420–430. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000282

Wakschlag, L. S., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Carter, A. S., Hill, C., Danis, B., Keenan, K., Kimberly, J., McCarthy, B. L., & Leventhal, B. L. (2007). A developmental framework for distinguishing disruptive behavior from normative misbehavior in preschool children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(10), 976–987. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01786.x

Warmuth, K. A., Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. T. (2020). Constructive and destructive interparental conflict, problematic parenting practices, and children’s symptoms of psychopathology. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(3), 301–311. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000599

Weber, L., Kamp-Becker, I., Christiansen, H., & Mingebach, T. (2019). Treatment of child externalizing behavior problems: A comprehensive review and meta–meta-analysis on effects of parent-based interventions on parental characteristics. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(8), 1025–1036. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1175-3

Weeland, J., Helmerhorst, K. O., & Lucassen, N. (2021). Understanding differential effectiveness of behavioral parent training from a family systems perspective: Families are greater than “some of their parts.” Journal of Family Theory & Review, 13(1), 34–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12408

Weyers, L., Zemp, M., & Alpers, G. W. (2019). Impaired interparental relationships in families of children with ADHD: A meta-analysis. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie, 227(1), 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000354

Yan, N., Ansari, A., & Peng, P. (2021). Reconsidering the relation between parental functioning and child externalizing behaviors: A meta-analysis on child-driven effects. Journal of Family Psychology, 35(2), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000805

Yoo, J. (2020). Relationships between Korean parents’ marital satisfaction, parental satisfaction, and parent–child relationship quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(7), 2270–2285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520921462

Zemp, M., Johnson, M. D., & Bodenmann, G. (2018). Within-family processes: Interparental and coparenting conflict and child adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(3), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000368

Zemp, M., Milek, A., Davies, P. T., & Bodenmann, G. (2016). Improved child problem behavior enhances the parents’ relationship quality: A randomized trial. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(8), 896–906. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000212

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

We declare that this manuscript is original, has not been published before and is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matalon, C., Turliuc, M.N. Parental self-efficacy and satisfaction with parenting as mediators of the association between children’s noncompliance and marital satisfaction. Curr Psychol 42, 15003–15016 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02770-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02770-3