Abstract

The present study examines employees’ prior victimization from bullying in school or at work as a predictor of 1) their current exposure to negative social acts at work and 2) the likelihood of labelling as a victim of workplace bullying, and 3) whether the link between exposure to negative acts at work and the perception of being bullied is stronger among those who have been bullied in the past. We tested our hypotheses using a probability sample of the Norwegian working population in a prospective design with a 5-year time lag (N = 1228). As hypothesized, prior victimization positively predicted subsequent exposure to negative acts, which in turn was related to a higher likelihood of developing a perception of being a victim of workplace bullying. However, contrary to our expectations, prior victimization from bullying did not affect the relationship between current exposure to negative acts at work and the likelihood of self-labelling as a victim. Taken together, the results suggest that employees’ prior victimization is a risk factor for future victimization, yet overall plays a rather modest role in understanding current exposure to negative acts and self-labelled victimization from bullying at work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Workplace bullying is a prevalent problem (León-Pérez et al., 2021; Nielsen et al., 2010) with severe negative effects on the health, well-being and productivity of targeted workers (e.g., Boudrias et al., 2021; Verkuil et al., 2015). Understanding antecedents and risk factors is therefore vital, and a prerequisite for designing effective interventions. At the individual level, interindividual differences assumed to be relatively stable over time, such as personality, have been widely studied as potential antecedents of bullying (Nielsen et al., 2017; Plopa et al., 2016; Podsiadly & Gamian-Wilk, 2016). However, we know less about the role of employees’ prior experiences in explaining future perceptions of exposure to bullying at work. In line with the more general revictimization phenomenon suggesting that victimization increases the likelihood of future victimization, conceptual models of workplace bullying propose that prior victimization from bullying increases the likelihood of later exposure to bullying at work (e.g., Einarsen et al., 2020; Samnani & Singh, 2016). Following a social information processing perspective (Crick & Dodge, 1996; Rosen et al., 2007), prior victimization may also influence the interpretation of future negative social interactions (e.g., Guy et al., 2017), thereby potentially putting prior victims at greater risk of future victimization experiences due to social information processing biases. The notion that employees’ personal history of victimization from bullying may influence their current perceptions and experiences of bullying at work has, however, rarely been examined empirically. Thus, the aim of the present study is to investigate the role of prior victimization from bullying in understanding employees’ current experiences of bullying at work.

In this, we contribute to the literature in several ways. First, using a two-wave design with a 5-year time lag with data from a probability sample drawn from the Norwegian workforce, we examine whether employees with a history of victimization from bullying are at greater risk of subsequently becoming victims of bullying at follow-up. Thus, in contrast to existing studies on the topic, our design enables us to rigorously examine whether the likelihood of changing victimization status at work during a 5-year period varies as a function of prior victimization experiences. This is one of few studies employing a large and representative sample when testing this revictimization prediction in a workplace setting. Thus, practitioners can benefit from learning how common prior victimization experiences are among employees, and to what extent such prior victimization puts employees at risk of later exposure to workplace bullying. Should revictimization be a prevalent problem, this would suggest that victims of bullying risk getting caught in a vicious cycle of victimization across the lifespan, providing yet another reason to design and implement interventions against bullying in schools and workplaces and to provide effective rehabilitative measures.

Second, we test the hypothesis that prior victimization has an indirect effect on the risk of developing a perception of being bullied at work via higher perceived exposure to negative acts at work, and that it is this indirect effect, as opposed a direct effect, that accounts for potential revictimization. Accordingly, by considering workplace bullying a two-step process (Nielsen et al., 2011; Nielsen & Knardahl, 2015), we contribute to the extant literature by providing a more nuanced exploration of the revictimization phenomenon than what has previously been done, thereby increasing our knowledge about how such revictimization occurs.

Finally, as the first study to date, we test employees’ prior victimization as a moderator that may strengthen the relationship between exposure to negative acts at work and self-labelled current victimization. Thus, we contribute to the literature on bullying and to the more general revictimization literature by exploring mechanisms underlying the revictimization phenomenon that are yet to be fully understood. Merely knowing that victimization in one context increases the risk of later victimization in another context may not, in itself, be all that helpful to victims or practitioners working with the prevention and handling of bullying cases. Identifying the mechanisms underlying revictimization from bullying is therefore a prerequisite for designing interventions that attenuates revictimization risk, and has potential benefits for both targeted employees, organizations, and society at large. More broadly, we respond to a call to acknowledge the importance of applying a temporal lens when studying interpersonal mistreatment at work (Cole et al., 2016), in our case by employing a prospective design to examine whether bullying experienced in the past influences the perception of current negative social acts encountered at work.

Theoretical Background

Bullying is defined as a process where an individual becomes the target of repeated negative social behaviours over time, and who, due to a pre-existing or evolving perceived power imbalance, has difficulties defending against the said negative treatment (Einarsen & Skogstad, 1996; Olweus, 1993). Thus, at its core, bullying is about exposure to negative acts that become increasingly systematic, frequent, and difficult to defend against as the process escalates. The negative social behaviours can be person-related (e.g., negative remarks about one’s person or private life) or work-related (e.g., repeated criticism of one’s work efforts, or someone withholding information which affects one’s performance), and take the form of direct (e.g., open ridicule) or indirect behaviours (e.g., gossip or social exclusion). Moreover, bullying is not an either-or phenomenon, and can be studied at different levels of escalation (e.g., Notelaers et al., 2006; Rosander & Blomberg, 2019), ranging from no exposure to negative acts to severe victimization where the target is frequently exposed to negative acts and has a perception of being victimized and unable to stop or defend against the negative treatment. Considerable empirical evidence has demonstrated that bullying at work has detrimental effects on factors such as health, well-being, and work participation among those targeted (for recent reviews, see Boudrias et al., 2021; Gupta et al., 2020; Mikkelsen et al., 2020; Nielsen & Einarsen, 2018). Given the severity of these outcomes, it remains a key task to identify and understand the risk factors for exposure to bullying at work.

Existing theoretical models show that workplace bullying is a multicausal phenomenon that no single theory or perspective can account for alone (Branch et al., 2021; Einarsen et al., 2020). However, two main mechanisms for the development of workplace bullying have been frequently studied. Simply put, the work environment hypothesis states that bullying at work is a result of work environment stressors or a poor social climate, which due to deficiencies in leadership and lack of conflict management are allowed to escalate into bullying (e.g., Leymann, 1996; Salin & Hoel, 2020). On the other hand, the individual disposition hypothesis states that the development of bullying can, at least in part, be explained by inter-individual differences in how employees act, perceive and react to events at work (e.g., Zapf & Einarsen, 2020). These differences can produce vulnerable and sensitive victims, that may appear weak and as easy targets who do not retaliate when faced with aggressive behaviours from others, or provocative victims, that act in ways that annoy or provoke others (Aquino, 2000; Olweus, 1978; Samnani & Singh, 2016). Some studies and theoretical notions also look at perpetrator characteristics rather than target characteristics in this respect (Zapf & Einarsen, 2020).

In the present study, we aim to expand our knowledge about the individual disposition hypothesis relating to targets. Whereas most previous research of person-level antecedents of workplace bullying focuses on stable personality dispositions, existing theoretical frameworks of workplace bullying also postulate that prior experiences of mistreatment from bullying may serve as a risk factor for later exposure to bullying at work (Einarsen et al., 2020; Samnani & Singh, 2016). Yet, this has rarely been elaborated upon conceptually or tested empirically. Thus, in the present study we draw on previously proposed mechanisms and empirical findings concerning individual risk factors for and outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying, to explore how prior victimization from bullying may increase the risk of later exposure to bullying at work. As has been elaborated upon elsewhere (e.g., Hoprekstad et al., 2020; Monks et al., 2009; Nielsen et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2003), widely accepted definitions of workplace bullying (e.g., Einarsen & Skogstad, 1996) and bullying in schools (e.g., Olweus, 1993) share evident similarities, and the established antecedents and outcomes of victimization across the two settings are comparable. Consequently, when exploring the impact of prior victimization from bullying among employees, we also consider prior victimization from bullying experienced in their school years. This approach aligns well with recent suggestions to take a broader perspective on bullying as a phenomenon (Boudrias et al., 2021) and to incorporate temporality and prior experiences in workplace mistreatment research (Cole et al., 2016).

Prior Victimization as a Predictor of Exposure to Bullying at Work

Revictimization refers to the phenomenon where individuals with a history of victimization have a higher risk of later becoming victims in new situations as compared to their counterparts without a history of victimization. While revictimization has been thoroughly documented in other fields, such as in the literature on childhood abuse and later sexual victimization (Walker et al., 2019), few investigations have been made into revictimization from bullying occurring among adult employees at work. Yet, several scholars have implied that employees who have been the victim of bullying previously in their lives are at higher risk of later exposure to bullying at work (e.g., Einarsen et al., 2020; Namie & Namie, 2018; Samnani & Singh, 2016; Smith et al., 2003). The basic premise for this proposed revictimization from bullying is easily derived from the conceptual model of bullying proposed by Einarsen et al. (2020). This model suggests that exposure to bullying not only has immediate and long-term detrimental effects on victims, but that these negative effects may also translate into individual characteristics that increase the risk of later victimization through mechanisms well known from the individual characteristics hypothesis of workplace bullying, such as coming across as a vulnerable or provocative victim (Olweus, 1978).

Many of the now established outcomes of exposure to bullying may indeed also serve as risk factors for later victimization. For instance, mental health problems such as depression and anxiety has been established both as an outcome of exposure to bullying at work (Boudrias et al., 2021) and in school, with effects lasting into adulthood (Lereya et al., 2015; Singham et al., 2017), and as a risk factor for later exposure to bullying at work (Nielsen et al., 2012; Rosander, 2021; Verkuil et al., 2015). Consequently, prior victims may risk getting caught in a vicious cycle of bullying where their initial victimization experiences cause sustained mental health problems, which then puts them at greater risk of experiencing victimization from bullying yet again in the future.

The same reasoning can be applied to a range of other outcomes of victimization from bullying that subsequently serve as risk factors for exposure to bullying at work, such as self-esteem (Aquino & Thau, 2009; Bowling & Beehr, 2006; Tsaousis, 2016; van Geel et al., 2018), dispositional hardiness (Hamre et al., 2020), aggressive behaviour (Ttofi et al., 2012), and social relationship problems (Glasø et al., 2009; Sigurdson et al., 2014). Overall, victimization from bullying seems to be related to a reduction in personal coping resources, which can predispose previously victimized employees to yet again become targets of bullying at work, for instance due to inefficient handling of work stressors (Van den Brande et al., 2016).

Existing studies have provided some empirical support for the link between prior victimization and exposure to bullying at work. In a cross-sectional study of 2215 Norwegian employees, prior victimization in school or at work was more prevalent among employees who currently self-labelled as victims of bullying, and especially among the “provocative victims” who also self-labelled as current perpetrators of bullying (Matthiesen & Einarsen, 2007). Similarly, those who retrospectively reported that they had been bullied in school were more likely to report that they were currently being bullied at work in a sample of 5228 British workers (Smith et al., 2003). Prospective studies have also found support for links between victimization from bullying in adolescence and subsequent higher exposure to bullying at work in young adulthood (Andersen et al., 2015; Hoprekstad et al., 2020), partially mediated by higher levels of symptoms of depression (Brendgen & Poulin, 2017).

Thus, there is some existing empirical support for the proposed link between prior victimization and later exposure to bullying at work. In the present study, we aim to test whether these results can be replicated in a probability sample of the Norwegian working population. We also extend and provide a more nuanced test of this revictimization hypothesis, by utilizing two measures capturing different aspects of exposure to bullying at work as our outcome variables. As noted by Nielsen and Knardahl (2015), workplace bullying can be considered a two-step process, where the first step involves systematic exposure to negative acts, and the second steps entails a subjective interpretation that these acts constitute bullying. This corresponds well with the two most commonly used methods for assessing bullying at work, namely the behavioural experience method, where employees are asked to report how often they have been exposed to a range of predetermined negative social behaviours in a given time period, and the self-labelling method, where employees are explicitly asked whether they have been bullied at work, often after first being presented with a definition (Nielsen et al., 2020). Accordingly, we test whether prior victimization relates both to current perceived exposure to a wide range of negative social acts at work that may be observed at different levels of bullying escalation (i.e., the behavioural experience method), and to the perception that this constitutes bullying (i.e., the self-labelling method). In doing so, we follow the recommendations of including both the behavioural experience method and the self-labelling method when studying exposure to workplace bullying (Nielsen et al., 2020). Based on the theoretical framework and empirical background presented above, it is reasonable to expect that prior victimization has bivariate relationships both with current perceived levels of exposure to negative acts and with the risk of currently labelling as a victim of workplace bullying.

-

H1: Prior victimization from bullying is positively related to current perceived exposure to negative acts at work

-

H2: Prior victimization from bullying is related to an increased likelihood of currently labelling as a victim of workplace bullying

Moreover, we argue that insofar as prior victimization from bullying is related to a higher risk of currently labelling as a victim of bullying at work, this effect is driven by current perceived exposure to negative acts at work as a mediator. Previous studies on this topic have relied solely on the behavioural experience method (Brendgen & Poulin, 2017; Hoprekstad et al., 2020) or the self-labelling method (Andersen et al., 2015; Matthiesen & Einarsen, 2007; Smith et al., 2003) as the outcome measure, and have thus not been able to examine the relationship between prior victimization from bullying and both measures of workplace bullying simultaneously. From the above reasoning regarding potential revictimization mechanisms, it follows that higher exposure to negative social behaviours at work likely drives the relationship between employees’ prior victimization from bullying and an increased probability of developing a perception of currently being a victim of workplace bullying. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

H3: Prior victimization from bullying has a positive indirect effect on the likelihood of currently labelling as a victim of bullying at work, via higher levels of current perceived exposure to negative acts at work

Prior Victimization as a Moderator of the Relationship between Exposure to Negative Acts and the Perception of Being a Victim a Workplace Bullying

There is a high degree of subjectivity involved in the perception of being bullied at work, and employees are likely to have different thresholds for labelling their exposure as bullying (Nielsen et al., 2020; Nielsen & Knardahl, 2015; Parzefall & Salin, 2010). In addition to increasing the risk of exposure to negative acts at work, we contend that prior victimization is likely to alter the way an employee perceives, interprets, and labels such negative acts. This notion is also evident in theoretical models of workplace bullying (Einarsen et al., 2020), and in line with the claim that current perceptions of interpersonal mistreatment are affected by employees’ retrospective mistreatment experiences (Cole et al., 2016).

This potential role of prior victimization can be understood in light of models detailing how prior life experiences affects interpretations of negative social interactions. For instance, according to the Social Information Processing (SIP) model (Crick & Dodge, 1994, p. 76), individuals’ interpretation of social situations are guided by their “memory database of past experience”, including social schemas. Accordingly, the model suggests that accumulated memories of prior victimization are likely to affect the interpretation of future negative social interactions. This is also a key notion of the victim schema model (Rosen et al., 2007, 2009), partly based on the SIP model, which postulates that individuals who have been frequently victimized develop a more easily accessible “victim schema” where they come to expect hostility and victimization from others, also when faced with more ambiguous situations or threats. According to the victim schema model, then, employees with a personal history of prior victimization from bullying can be expected to more easily recognize negative social behaviours as bullying and more readily have their victim schemas activated and identify with the victim role. In support of these models, prior victimization has been consistently linked to more hostile attributions and expectations of exclusion, an increased attention for negative social cues, and more negative evaluations of others and oneself (Guy et al., 2017; van Reemst et al., 2016; Ziv et al., 2013). Overall, then, previous research suggests that social information processing differences caused by prior victimization may lead to a lower threshold of labelling as a victim of bullying when faced with exposure to negative social behaviours at work.

In a similar line of reasoning, workplace bullying can be considered a traumatic experience with the potential to shatter basic assumptions and alter social schemas, in accordance with the cognitive theory of trauma (Janoff-Bulman, 1989; Mikkelsen & Einarsen, 2002). In the same manner as described in the SIP model, these basic assumptions or social schemas guide our interpretation of future situations, and we more readily accept and incorporate information from the environment that fits with our existing schemas. Consequently, employees who are prior victims of bullying may be more inclined to interpret exposure to negative social behaviours at work in light of their pre-existing negative basic assumptions of the world and others as malevolent, as victims of bullying at work have been shown to display more negative views about themselves, other people and the world (Mikkelsen & Einarsen, 2002; Rodriguez-Munoz et al., 2010). Employees without prior victimization experiences, on the other hand, may have an ‘illusion of invulnerability’ typically displayed by non-victims (Janoff-Bulman, 1989, p. 169) and a more idealistic world view (Namie & Namie, 2018) that do not fit well with the notion of being a victim, consequently having a higher threshold for labelling as victims of workplace bullying.

Overall, there are convincing theoretical arguments linking prior victimization from bullying to a lowered threshold for perceiving exposure to negative social acts at work as bullying. If that is the case, such a lowered threshold could, at least in part, explain why previous studies have found that employees with prior victimization experiences are more likely to identify as victims of bullying at work. To the best of our knowledge, however, this potential moderating effect of prior victimization on the relationship between exposure to negative acts and the perception of being bullied has not yet been empirically tested.

-

H4: The positive relationship between current exposure to negative acts at work and the perception of currently being bullied at work is stronger among employees who have (vs. have not) been bullied in the past

Method

Design and Sample

The present study is an extension and re-analysis of data from a randomly drawn sample representative of the Norwegian working population, collected over two waves separated by 5 years (see also Einarsen & Nielsen, 2014; Glambek et al., 2016; Glambek et al., 2020, who investigated outcomes of exposure to bullying over time). At baseline (T1, in 2005), 4500 individuals randomly drawn from the Norwegian employment register were invited to participate, and 2539 individuals (56.4%) completed and returned the survey. Five years later (T2, in 2010), the individuals who had participated in the first wave were invited to participate in a follow-up survey, which resulted in returned questionnaires from 1613 (64.5%) individuals. Of these, 1318 (81.7% of those who had responded) reported that they were still in employment, and these employees were thus eligible to answer the items in the questionnaire about their current experiences at work. Thirty-seven individuals (2.3%) did not report on their current employment status. The remaining 258 individuals (16.0%) were no longer in employment (e.g., had become unemployed, students, retired or receiving disability benefits), and were therefore not in a position to answer questions about their work environment at follow-up. Statistics Norway drew the sample and carried out the data collection, and each respondent was assigned a random ID number to match their responses over time.

In the present study, we included employees who a) provided data about prior bullying experiences, b) did not identify as currently bullied at work at baseline, and c) provided data about their current exposure to negative acts and self-labelled victimization status at follow-up 5 years later, providing a sample of 1228 employees. By only including employees who did not identify as currently bullied at work at baseline, we ensured that we were able to examine whether prior experiences of bullying could predict new and unrelated cases of bullying at work at a much later stage. Thus, this exclusion ensured that our analyses predicted a shift from currently not bullied at baseline to bullied at follow-up and allowed us to examine whether the likelihood of developing a perception of being a victim of bullying at work depended on prior and unrelated victimization experiences. Moreover, by separating the measures of prior (T1) and current victimization (T2), we avoided the possibility that any ongoing victimization from bullying at work affected reports of prior victimization.

In our final sample, 53.4% were women, the mean age was 43.5 (SD = 10.3), and 20.7% had managerial responsibilities. The majority were working full-time (76.1%). Note that more details about the procedure and sample is available in previous publications based on the same overall data collection (e.g., Einarsen & Nielsen, 2014).

Instruments

Self-Labelled Victimization from Workplace Bullying

Self-labelled victimization from workplace bullying was measured at baseline (T1) and at follow-up 5 years later (T2), using a validated single item (Einarsen & Skogstad, 1996; Nielsen et al., 2020; Solberg & Olweus, 2003). The respondents first read the following definition of bullying, highlighting the conceptual properties of the phenomenon such as duration, repetitiveness of the exposure and perceived power imbalance (Einarsen & Skogstad, 1996; Olweus, 1993), and where then asked to state whether they had been bullied during the last 6 months according to the definition:

Bullying (such as harassment, teasing, exclusion or hurtful jokes) is when an individual is repeatedly exposed to unpleasant, degrading, or hurtful treatment at work. For a situation to be labelled bullying, it has to occur over a certain time period, and the target has to have difficulties defending himself or herself against the actions. It is not bullying if two equally “strong” persons are in conflict or if it is a one-off incident.

The response alternatives ranged from “No” (1) to “Yes, several times a week” (5). Given our research interest in whether the respondents had a perception of being bullied, we dichotomized this item by categorizing all respondents who had answered “Yes” to this item as bullied. This approach has also been used in several previous studies (e.g., Ågotnes et al., 2018; Vie et al., 2010). In order to test prior victimization as a risk factor for developing a perception of being bullied at work at follow-up, we excluded the 108 respondents who according to themselves were bullied at baseline from further analyses. Thus, any employees left in the analyses who had the perception of being bullied at work at follow up (T2) represent new cases of bullying as compared to baseline (T1).

Prior Victimization from Bullying

Prior victimization from bullying was measured at baseline (T1) using two items presented after the self-labelling item described above, and the respondents were thus familiar with the definition of bullying. The respondents were asked to state the extent to which they had been bullied in primary and secondary school, and the extent to which they had been bullied at work more than 6 months ago, with response options ‘No, never’ (1), ‘Yes, in a single time period’ (2) and ‘Yes, in several different time periods’ (3) for bullying at school, and ‘No’ (1) and ‘Yes’ (2) for prior bullying at work. We categorized respondents who at baseline reported that they had been victims of bullying either in school or previously at work as prior victims of bullying.

Exposure to Negative Acts at Work

Exposure to negative acts at work was measured at baseline and follow-up using the 22-item Negative Acts Questionnaire–Revised (NAQ-R; Einarsen et al., 2009). This questionnaire measures exposure to a range of negative social behaviours over the last 6 months that the exposed employee may perceive as constituting a bullying situation if experienced repeatedly and over time but does not mention the term “bullying”. Consequently, the NAQ-R covers exposure to a range of negative social behaviours that taken together the target may or may not interpret as constituting bullying. The NAQ-R was presented to the respondents prior to the self-labelling item and the bullying definition. Example items include “Being ignored and excluded”, “Hints or signals from others that you should quit your job” and “Repeated reminders of your errors and mistakes”. The response alternatives ranged from “Never” (1) to “Daily” (5). We computed a composite measure comprised of the total score of the 22 items, as has been done extensively in existing research using the NAQ-R (see Nielsen et al., 2020). Thus, a higher score on the NAQ-R represents a higher perceived frequency of exposure to negative and bullying-like acts at work over the past 6 months. The NAQ-R had acceptable reliability at baseline (ω = .84, 95% CI [.82, .85]) and at follow-up (ω = .86, 95% CI [.85, .87]). For the analyses, we standardized the NAQ-R total score to ease interpretation of the results.

Statistical Analyses

We tested our hypotheses within a Bayesian framework, which is especially well suited for modelling indirect effects that are typically heavily skewed, as it produces a credibility interval that allows for asymmetric distribution of parameter estimates (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2012). Moreover, the Bayesian framework enables researchers to evaluate the relative support both for and against a null hypothesis given the data at hand, thereby enabling a more informative interpretation of relationships being studied compared to a classical frequentist approach. We estimated our models using the Bayesian estimator in Mplus 8.0, which uses MCMC chains obtained using the Gibbs sampler algorithm to generate the posterior distribution of the parameters (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2012). We used the Mplus default diffuse parameter priors, and, besides allowing for asymmetrical distribution of parameter estimates, the estimates are thus close to what would have been obtained using a ML estimator (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2012). We tested the bivariate hypotheses (H1 and H2) using a simple probit (H1) and linear regression (H2) and tested our proposed indirect effect (H3) and interaction (H4) using Bayesian path analyses.

Model parameters were evaluated using the 95% credibility interval, along with Bayesian one-tailed p values denoting the probability that the effect is in the opposite direction (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2012). We also report the Bayes Factor (BF) where applicable, which provides a quantification of the relative evidence for and against a model and thus enables substantiated claims of the existence or non-existence of relationships (Kass & Raftery, 1995). The BF is a continuous measure of relative evidence, and BF > 1 indicates more support for the hypothesis being tested relative to the alternative, while BF > 3 has been suggested as a threshold between ‘not worth more than a bare mention’ and ‘positive’ or ‘substantial’ evidence (Kass & Raftery, 1995), comparable to the p < .05 threshold. It should also be noted that many scholars advise against thresholds for the BF and argue it should simply be treated as a continuous measure of evidence and evaluated in light of the context of the analysis (e.g., Van Lissa et al., 2020). As the computation of the BF is not yet implemented in Mplus, we report BFs obtained using BFpack (Mulder et al., 2019) in R version 4.0.3 (R Core Team, 2020), based on Bayesian regression estimates from rstanarm version 2.21.1 (Goodrich et al., 2020) obtained using the No-U-Turn Sampler to generate the posterior parameter distributions and employing default priors with autoscaling enabled. BFpack employs a default Bayes factor methodology, and thus enables computation of the BF without requiring users to specify subjective priors. We performed attrition analyses using Bayesian chi square and t-tests in JASP v. 0.14.0 (JASP Team, 2020), using default priors.

We ran the analyses using two Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains with 50,000 iterations in each chain to ensure sufficient precision in the posterior distribution. The first half of each chain was discarded as the burn-in phase, and in our case the posterior distribution is thus made up of a total of 50,000 iterations. We checked for convergence by using Potential Scale Reduction (PSR) values close to 1 as an indicator of small between-chain parameter variation relative to the within-chain variation and thus convergence across chains (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2012), and visually inspected the posterior parameter trace plots, which indicated good mixing for the estimated models. We evaluated overall model fit for the path model using the posterior predictive p value, with a value close to .5 and a 95% confidence interval for the difference between the observed and replicated chi-square with intervals crossing zero indicating good fit (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2012).

Whether or not the respondent had the perception of currently being bullied at work was used as the focal dependent variable in the path model testing H3 and H4. Prior victimization from bullying was entered as the main predictor of current victimization perceptions, and current exposure to negative acts as the mediator. Moreover, we included exposure to negative acts at baseline as a covariate predicting current exposure to negative acts, to test whether prior victimization predicted an increase in exposure to negative acts compared to baseline levels. We created the interaction term by multiplying prior victimization and current exposure to negative acts using the define command in Mplus and included a path from the interaction term to current victimization perceptions. We then used the MOD command in Mplus to generate estimates of counterfactually-defined causal effects, which is preferable to the conventional a × b product approach when testing indirect effects with a X × M interaction and a binary Y (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2015; Rijnhart et al., 2020). Thus, we estimate the indirect effect while incorporating X (prior victimization) as a moderator of the relationship between M (current exposure to negative acts) and Y (current perception of being bullied at work). Following the Mplus default settings for Bayesian path analyses with a binary outcome, the path model was estimated using a probit link for the binary outcome. Thus, the estimate of the path from prior victimization to current perceived exposure to negative acts is a normal regression coefficient, while the paths to current victimization from bullying are probit coefficients. To aid the interpretation of the results, we also report the Odds Ratios (ORs) for the direct and indirect effect. In the initial analyses, we included gender, age, and whether the respondent had managerial responsibilities as covariates. However, as these variables did not predict exposure to negative acts or the perception of being a victim of bullying in the multivariate analyses nor had any impact on the hypothesis tests, we report the results of the multivariate analyses without these covariates (Becker et al., 2016).

Results

Attrition Analyses

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the respondents who responded at both time points compared to those who only responded at baseline (dropouts), as well as for our final sample.

Attrition analyses revealed that dropouts were younger (M = 41.3, SD = 11.6) compared to follow-up respondents (M = 45.2, SD = 11.2, BF10 = 4.1 × 1013). The evidence was inconclusive regarding the impact of gender (BF01 = 1.4) and baseline exposure to negative acts (BF01 = 2.4) on dropout, although the evidence favoured the null hypothesis of no relationship. We did not find any other reliable differences between dropouts and follow-up responders on baseline characteristics.

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for the study variables are displayed in Table 2. There was a strong, positive correlation between T2 exposure to negative acts and T2 self-labelled victimization from bullying. Moreover, T1 prior victimization had moderate, positive correlations with T2 exposure to negative acts and T2 self-labelled victimization from bullying.

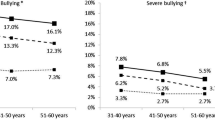

Of the 1228 employees in the sample who did not identify as currently being bullied at work at baseline, 35.2% (n = 432) reported that they had been bullied previously in their life, either only in school (31.4%, n = 385), only at work (1.4%, n = 17) or both in school and at work (2.4%, n = 30). At follow-up 5 years later, 3.0% of the employees (n = 37) reported that they had been bullied at work the past 6 months and had thus changed from not bullied to bullied during the 5-years period.

Hypothesis Tests

Employees with a history of prior victimization from bullying reported higher exposure to negative acts at work at follow-up (M = 27.08, SD = 6.39) compared to employees without prior victimization experiences (M = 25.02, SD = 3.95). Accordingly, a Bayesian simple linear regression analysis showed that prior victimization had a positive effect on subsequent exposure to negative acts (median estimate = 0.41, 95% credibility interval [0.29, 0.53], one-tailed p = .00, R2 = .038, 95% credibility interval R2 [.02, .06]), with a corresponding BF providing decisive support for a positive relationship compared to the coefficient being zero (BF = 1.76 × 109). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported. Prior victimization also had a positive effect on current exposure to negative acts (T2) when baseline exposure to negative acts (T1) was included as a covariate in the model (median estimate = 0.25, 95% credibility interval [0.15, 0.36], one-tailed p = .00, BF = 5344), and explained 1.5% of the variance in current exposure to negative acts after adjusting for baseline exposure. Thus, prior victims were more likely to experience an increase in exposure to negative acts at work during the 5-years period from baseline to follow-up.

A higher proportion of employees with a history of prior victimization developed a perception of being bullied at work at follow-up (5.6%, n = 24 of 432) compared to employees without prior victimization experiences (1.6%, n = 13 of 796). A Bayesian simple probit regression analysis showed that employees with a history of prior victimization were over 3 times more likely to develop a perception of being bullied at follow-up (OR = 3.55, 95% credibility interval [1.52, 6.71], one-tailed p = .00), with a corresponding BF10 = 42.6 strongly favouring the observed difference relative to the null hypothesis of no differences between the two groups. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was also supported.

We tested the hypothesized indirect effect (H3) and interaction (H4) using Bayesian path modelling. The results are summarised in Fig. 1.

Path estimates for the hypothesized model (N = 1228). Note. Median parameter estimates are displayed. Estimates are based on 50,000 MCMC samples. Numbers in brackets represent the 95% credibility interval. OR = Odds Ratio. P = Bayesian one-tailed p-values denoting the proportion of the posterior distribution in the opposite direction

The proposed model, including the indirect effect of prior victimization on victimization status via current (T2) perceived exposure to negative acts, as well as the interaction between prior victimization and current perceived exposure to negative acts, showed acceptable fit to the data (PPI = .488, 95% credibility interval [−17.05, 17.80]). However, the posterior distribution for the path from the interaction term to current self-labelled victimization from bullying indicated that the data did not support a positive interaction effect, with a median estimate of -0.11, a credibility interval indicating a 95% probability that the true value was between -0.35 and 0.14, and a 19% probability that the interaction coefficient was positive (median estimate = -0.11, SD = 0.12, 95% credibility interval [-0.35, 0.14], one-tailed p = .19). Moreover, the data provided 67 times more support for the interaction effect being zero compared to being positive (BF01 = 67.9), and 12 times more support for the interaction being zero compared to being negative (BF01 = 12.1). Thus, the results indicated strong evidence against the proposed interaction between prior victimization and current exposure to negative acts as a predictor of current self-labelled victimization from bullying. Consequently, Hypothesis 4 was not supported.

After removing the interaction term from the model, we reran the analyses replacing the “MOD” command with the “IND” command in Mplus to obtain estimates of counterfactually-defined direct and indirect effects without an X × M interaction. The revised model also showed acceptable fit to the data (PPP = 0.481, 95% credibility interval = [-14.86, 15.36]. In line with the bivariate analyses, the path analysis indicated that prior victims of bullying experienced higher levels of exposure to negative acts at work at follow-up (b = 0.25, SD = 0.05, 95% credibility interval = [0.15, 0.36], one-tailed p < .001), after adjusting for baseline (T1) exposure to negative acts. The median estimate indicated that having prior victimization experiences was related to a 0.25 SD increase in exposure to negative acts at follow-up compared to baseline levels of exposure. When considered simultaneously, the path estimates suggested that current exposure to negative acts at work (b = 0.52, SD = 0.06, 95% credibility interval = [0.41, 0.64], one-tailed p < .001), but not prior victimization from bullying (b = 0.24, SD = 0.18, 95% credibility interval = [-0.11, 0.60], one-tailed p = .089), was related to an increased probability of currently labelling as a victim of bulling at work. The corresponding BF for the prior victimization coefficient indicated that the data provided 7 times more support for the relationship being zero than positive (BF01 = 7.9). Similarly, the estimate for the counterfactually-defined pure natural direct effect of prior victimization on current perceptions of being bullied suggested that a direct effect was not consistently supported by the data, with a 95% credibility interval for the OR including 1 (OR = 1.73, 95% credibility interval [0.61, 3.53]). Thus, the results indicated that prior victimization did not have a direct effect on the probability of currently self-labelling as a victim of bullying when current exposure to negative acts was included in the model. Finally, the estimates for the counterfactually-defined total natural indirect effect showed that prior victimization had a positive indirect effect on the probability of developing a perception of being bullied via an increase in exposure to negative acts (OR = 1.33, 95% credibility interval [1.17, 1.51], one-tailed p < .001). In other words, the results indicated that there is a 95% probability that the true OR for the indirect effect was between 1.17 and 1.51, with the median estimate suggesting that prior victimization was related to a 33% increased probability of developing a perception of being bullied, via an increase in exposure to negative acts. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Supplemental Analyses

Next, we carried out several post-hoc analyses to assess the robustness of our findings, inspired by comments from reviewers. First, we tested a model where we included exposure to negative acts at baseline as one of the predictors of self-labelled victimization at follow-up. This path was not reliably different from zero and its inclusion did not impact the other estimates, and we therefore left it out of the final analyses presented above.

Second, we reran all analyses without excluding the 108 employees who self-labelled as victims of bullying the last 6 months at baseline. The results of these analyses were very similar to our original analyses, with the same conclusions for our hypotheses tests.

Third, we ran our analyses without dichotomizing self-labelled victimization at follow-up, declaring the variable as categorical in Mplus. These results were only trivially different from our main analyses and led to the same conclusions regarding our hypotheses. Next, we estimated a two-part semicontinuous model to test whether prior victimization could predict both a) whether respondents developed the perception of being bullied at follow-up (the binary part), and b) the perceived frequency of victimization at follow-up among those who labelled as victims at follow-up (the continuous part). As expected, the results for the binary part of the model were the same as for the models presented above. However, the estimates for the perceived frequency of victimization did not converge and were too unstable to be considered reliable based on the trace plots from the MCMC sampler, suggesting that we did not have sufficient new victims at follow-up to examine perceived frequency of victimization as an outcome.

Finally, to check that the results hold across different analytical strategies, we tested our models using the maximum likelihood estimator in Mplus and evaluated the indirect effect using the a × b product method. Also using this approach, H1, H2, and H3 were supported, whereas the interaction hypothesis (H4) was not. Thus, the results hold across different analytical approaches.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to examine the links between employees’ prior victimization from bullying, either in school or at work, and their subsequent exposure to negative acts at work and likelihood of developing the perception of being a victim of workplace bullying. The results indicated that employees with a history of victimization from bullying had a somewhat higher risk of later reporting exposure to negative social acts at work, which fully accounted for their somewhat higher likelihood of developing a perception of being bullied at work. On the other hand, and contrary to our hypothesis, prior victimization did not affect the strength of the relationship between exposure to negative acts and the probability of developing a perception of being a victim of bullying.

Theoretical Contributions

Our findings support the proposition in broad conceptual models of workplace bullying (Einarsen et al., 2020; Samnani & Singh, 2016) that employees who have a history of victimization from bullying are at increased risk of subsequent exposure to bullying at work. As such, our findings are consistent with previous studies linking a history of victimization from bullying with an increased likelihood of later exposure to bullying-like negative acts at work (Brendgen et al., 2021; Brendgen & Poulin, 2017; Hoprekstad et al., 2020) and self-labelling as a victim of workplace bullying (Andersen et al., 2015; Matthiesen & Einarsen, 2007; Smith et al., 2003). Taken together, then, the empirical evidence now suggests that revictimization as a phenomenon, thoroughly studied in other contexts (e.g., Walker et al., 2019), is also relevant for understanding the development of bullying and other related forms of mistreatment at work.

Extending previous work, our findings indicate that prior victimization only affects the likelihood of developing a perception of being bullied via higher perceived levels of exposure to negative social acts at work. As such, following the recommendation to employ both the behavioural experience method and the self-labelling method (Nielsen et al., 2020) not only allows for testing the same hypothesis in different ways, but also allows for explicitly modelling the relationship between the two measures capturing different aspects of the bullying phenomenon. Our findings nuance the revictimization phenomenon by showing that the heightened probability of developing a perception of being bullied among prior victims does not exist without a certain level of perceived current exposure to negative social behaviours. While models of social information processing (Crick & Dodge, 1996; Rosen et al., 2007) suggest that prior victimization leads to a more accessible and more easily activated “victim schema”, our results do not suggest that such mechanisms are driving the increased likelihood to develop the perception of being bullied among prior victims. Thus, there must be “something there” in terms of perceived negative behaviours from others both for employees with and without a history of prior victimization to label their current situation as bullying. Yet, considering the proposed social information processing mechanisms, it is also possible that prior victims are better at recognizing negative social acts or more inclined to ascribe hostility or negative intent to ambiguous social interactions. As such, without presenting the respondents with the same objective stimuli, we cannot rule out the possibility that interpretational biases in part explain the difference in perceived exposure to negative social behaviours between employees with and without prior victimization experiences.

In contrast to our predictions based on models highlighting the role of prior life experiences in making sense of current social interactions (e.g., Crick & Dodge, 1994; Janoff-Bulman, 1989; Rosen et al., 2009), the relationship between perceived exposure to negative acts at work and self-labelled victimization from workplace bullying was not moderated by prior victimization experiences. This suggests that once an employee has perceived that they are being exposed to a certain level of negative social behaviours at work, any heterogeneity in the interpretation of this situation as constituting bullying or not does not seem to stem from the employee’s prior experiences with bullying. As such, our results do not correspond well with previous studies linking victimization to social information processing biases (e.g., van Reemst et al., 2016). This could, of course, indicate that the notion of prior victimization as a predictor of the perception and interpretation of future negative social interactions does not apply among adult employees in a workplace context. Combined with previous failed attempts to identify individual level moderators of the link between perceived exposure to negative acts at work and self-labelled victimization (Vie et al., 2010), our results may also suggest that more proximal contextual variables related to the exposure itself may be more important for the perception of being bullied at work.

Alternatively, our findings may be taken as a reminder of the importance and challenges of taking a critical temporal perspective in research on workplace bullying and other types of interpersonal mistreatment at work (Cole et al., 2016). Specifically, models of social information processing suggest that individuals continuously update their own “database” and social schemas after facing new social interactions (Crick & Dodge, 1994). The time passed since the prior victimization experience and the assessment of current experiences of bullying at work was at least five and a half years in the present study, and for most cases significantly longer, as they had experienced their prior victimization during their school years. Therefore, employees with prior victimization experiences in our sample are likely to have experienced plenty of positive social interactions in the substantial amount of time following their prior victimization that may balance out any social information processing biases incurred and make them fade with time (van Reemst et al., 2016). Thus, just as victimization experiences can negatively affect individuals’ social schemas and expectations, so can fundamental positive assumptions and schemas about the benevolence of the world, oneself and others be rebuilt (Janoff-Bulman, 2004). In addition, individuals may differ in their temporal orientation, such that prior victimization experiences may to a larger extent be a predictor of perceptions and interpretations of current mistreatment among individuals with a temporal focus towards the past (Cole et al., 2016).

Finally, it is important to consider our design when interpreting the interaction result. Asking respondents to retrospectively assess their exposure to negative social acts the last 6 months is a common and well-established approach in research on workplace bullying (e.g., León-Pérez et al., 2021; Notelaers & Van der Heijden, 2021). However, it is possible that interpretational differences between employees facing negative social behaviours at work are better captured in the heat of the moment and in the interpretation of specific events, as opposed to in retrospective aggregations of events. For instance, an employee who has had 6 months to contemplate the meaning of the situation they are in is presumably less likely to be affected by distant victimization experiences compared to an employee that in the lunch break is trying to make sense of an ambiguous comment made in a morning meeting. As such, models of altered social information processing following prior victimization (e.g., Crick & Dodge, 1996; Janoff-Bulman, 1989; Rosen et al., 2007) may still be relevant for understanding the perception and interpretation of negative social acts at work if more dynamic approaches are used. Accordingly, experience sampling methods should be employed to get a better grasp of this issue, as has already been done in other aspects of workplace bullying research (e.g., Ågotnes et al., 2020; Baillien et al., 2017; Hoprekstad et al., 2019; Rodriguez-Munoz et al., 2020).

Limitations and Future Research

There are several methodological considerations that should be noted when interpreting the results of the present study. First, although using a two-wave design with a 5-year interval enabled us to clearly separate the prior victimization temporally from any current victimization and allowed sufficient time for the development of new perceptions of being bullied at work, having more frequent and time-intensive data collections could have enabled us to study the dynamics of the development of the perception of being bullied more precisely. For instance, it is possible that some of the respondents who we classified as new victims of bullying at follow-up after 5 years, developed their perception of being bullied at work earlier than this. Thus, if a respondent had the perception of being bullied already after, say, 3 years, the level of exposure to negative acts at follow-up may not be that important for their current perceived victimization status.

Second, due to the unbalanced prevalence of victimization experiences in school during childhood and adolescence (33.8%) and previously at work during adulthood (3.8%) in our sample, the category of prior victims consisted mainly of employees who were previously bullied at school rather than at work. As a result, we have not been able to examine whether the potential effect of prior victimization from bullying on current appraisals of negative social acts at work is moderated by details of the prior victimization, such as where (i.e., at school or at work) or when (i.e., relatively recently vs. several decades ago) the prior victimization took place. Additional aspects relating to the prior victimization would also be interesting to investigate in future studies, such as the number of perpetrators (Glambek et al., 2020), the type of bullying behaviours, the mental health impact of the prior victimization, or the extent to which the employee perceived that he or she coped with the prior victimization in an effective manner (Smith et al., 2003). Thus, it is possible that examining details of the prior victimization rather than prior victimization as such is a better approach for understanding the links between prior victimization and current outcomes.

Third, we estimated our indirect effect model using data collected at two measurement occasions, where our proposed mediator and outcome were measured at the same time. Strictly speaking, then, our data does not enable us to reject an alternative model in which the current perception of having been bullied the last 6 months increases the retrospectively reported exposure to negative social acts at work the last 6 months, as data generated from a X➔M➔Y model also tend to support an alternative X➔Y➔M model (Lemmer & Gollwitzer, 2017; Thoemmes, 2015). However, although we do not have sequential time-ordering of our mediator and outcome, we have a conceptual time-ordering (see Tate, 2015) of our variables due to how they were measured, as the level of exposure to specific negative acts during the last 6 months logically precedes the employees’ current judgement of whether that exposure constituted bullying or not. That is, exposure to negative acts the past 6 months is less like to follow from current judgements. Still, we may need more intensive data collection strategies to fully rule out the alternative X➔Y➔M model.

Fourth, we relied on self-report data, which has its obvious advantages when examining employee perceptions of workplace bullying. Still, the use of self-report data does not come without its limitations and risk of inflated estimates due to common source variance. Yet, temporal separation of measurements, as in the current study, in part remedies the impact of this bias (e.g., Podsakoff et al., 2012).

Fifth, dichotomizing measures, as we have done with self-labelled victimization from bullying, is generally not considered advisable, as it removes information and potentially attenuates parameter estimates. In this instance, however, dichotomizing the self-labelling measure allowed us to investigate the qualitative shift in perception from “not bullied” to “bullied” that aligned well with the aims of this study. That said, we also had too few new victims of bullying in our sample to reliably explore whether prior victimization was linked to perceived frequency of victimization from bullying at follow-up in addition to the shift from “not bullied” to “bullied”.

Sixth, as noted in the method section, this study is based on a larger project that has also provided data to previously published studies (e.g., Einarsen & Nielsen, 2014). Consequently, aspects such as sample demographics and rates of exposure to negative acts and victimization from bullying at work are not unique to this study, which should be considered by anyone doing, for instance, meta-analyses on the prevalence of workplace bullying. That said, the findings related to our hypotheses are novel and have not been published previously, as no other publications using data from the same project have used the data on prior victimization from bullying.

Finally, the incidence of 3.0% new self-labelled victims of workplace bullying after a 5-years period corresponds reasonably well to the relatively low prevalence of bullying in Norway compared to other countries (Nielsen et al., 2009; Notelaers & Van der Heijden, 2021). Nonetheless, this low prevalence limits the kinds of statistical analyses that can be reliably performed using otherwise high-powered samples. For instance, it prevented us from doing reliable subgroup analyses to test whether the hypothesized moderating effect of prior victimization only exists at relatively low levels of perceived exposure to negative acts, which could be more likely to be perceived as ambiguous and thus more subject to interpretational differences. Although we had a sufficient number of new victims to test our interaction hypothesis judging by the resulting Bayes factor indicating “positive” to “very strong” support for the null hypothesis (Jeffreys, 1961; Kass & Raftery, 1995), the issue of how large the Bayes factor should be to conclude that there is sufficient data to reject or support a null hypothesis is also debatable. Thus, substantially larger samples or a more purposeful sampling of victims of bullying might be needed in future studies testing similar hypotheses in an even more exhaustive manner, in line with recent analyses showing that several studies purportedly studying bullying have not necessarily managed to sample enough victims (Notelaers & Van der Heijden, 2021).

Conclusion and Practical Implications

The findings of this study have several practical implications. First, our findings stress the necessity of measures to prevent and stop bullying situations in schools and at workplaces and tertiary measures to rehabilitate victims of bullying, as employees with a history of victimization from bullying continue to be at higher risk of subsequent exposure to bullying at work many years following their initial victimization. Thus, victimization from bullying appears to be harmful not only to the health and well-being of the victims in the short term, but also seems to foster a vicious cycle wherein the prior victims are at higher risk of subsequent mistreatment at work. Preventing and stopping bullying cases in a timely manner is therefore crucial for the long-term outcomes of individuals targeted.

Second, prior victimization only explained some 2-6% of the variance in exposure to negative acts, which is similar to previous estimates (Hoprekstad et al., 2020). Moreover, 94.4% of those previously bullied had not developed a perception of being bullied at work at follow-up, also in line with previous findings that the vast majority of those previously bullied are not subsequently bullied at work (Smith et al., 2003). In other words, the victimization history of employees seems to play a very modest role in the development of bullying at work. Still, findings from vignette studies indicate that witnesses’ hypothetical helping behaviour and causal attributions of blame are affected by knowledge about the victim’s prior victimization experiences (Desrumaux et al., 2016; Desrumaux & De Chacus, 2007). Against this backdrop, our findings suggest that managers, HR-personnel, and other practitioners responsible for preventing and handling cases of workplace bullying ought to look elsewhere than at the victimization history of employees when trying to pinpoint the major developmental causes of bullying at work. Relatedly, as our results suggest that prior victims are no more likely than others to self-label as victims of bullying given the same level of exposure to negative social behaviours, any lay perceptions of victims of bullying as being overly sensitive or dramatic when claiming victim status seem to be unwarranted.

Finally, in accordance with previous theoretical notions on the importance of individual factors in explaining workplace bullying (e.g., Zapf & Einarsen, 2020), it is important to stress that even if individual-level variables do play a role in the development of workplace bullying, it remains a managerial responsibility to address the issue in order to keep all employees safe from such harm. Thus, this line of research should not be understood as condoning any form of “victim blaming”, as empirically unravelling risk factors at different levels by no means justifies mistreatment as enacted by perpetrators. On the contrary, findings about any individual level risk factors for becoming a target of bullying could serve as a starting point for systematically examining when and why some employees become perpetrators of bullying, and as such form the basis for interventions aimed at the enactment of bullying behaviours at work. This is in line with a perpetrator predation lens for understanding individual risk factors for mistreatment at work, which shifts the focus away from scrutinizing the victims, and towards the agency and responsibility of perpetrators (Cortina, 2017).

In light of recent meta-analyses emphasizing that individual differences have low predictive power in explaining mistreatment at work compared to situational factors (e.g., Dhanani et al., 2020), our findings suggest that future studies examining individual differences as antecedents of workplace bullying will do wise to adopt a person-environment fit perspective by simultaneously considering situational factors. Taking such an approach, Reknes et al. (2019) found that dispositional affect, trait anger and trait anxiety predicted exposure to bullying behaviours especially when the employee faced high levels of role conflict at work, whereas the impact of these traits diminished substantially at lower levels of role conflict. In the same vein, future studies could explore whether prior victimization acts as a moderator of other established antecedent–bullying relationships, thereby increasing our understanding of the mechanisms driving the revictimization phenomenon.

Data Availability

The survey data that was analysed in this study are available from NSD - Norwegian centre for research data, at https://doi.org/10.18712/NSD-NSD2050-V1 and https://doi.org/10.18712/NSD-NSD1262-V1, or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Andersen, L. P., Labriola, M., Andersen, J. H., Lund, T., & Hansen, C. D. (2015). Bullied at school, bullied at work: A prospective study. BMC Psychology, 3(1), 35.

Aquino, K. (2000). Structural and individual determinants of workplace victimization: The effects of hierarchical status and conflict management style. Journal of Management, 26(2), 171–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600201

Aquino, K., & Thau, S. (2009). Workplace victimization: Aggression from the target's perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 717–741. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163703

Baillien, E., Escartín, J., Gross, C., & Zapf, D. (2017). Towards a conceptual and empirical differentiation between workplace bullying and interpersonal conflict. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2017.1385601

Becker, T. E., Atinc, G., Breaugh, J. A., Carlson, K. D., Edwards, J. R., & Spector, P. E. (2016). Statistical control in correlational studies: 10 essential recommendations for organizational researchers. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(2), 157–167.

Boudrias, V., Trépanier, S.-G., & Salin, D. (2021). A systematic review of research on the longitudinal consequences of workplace bullying and the mechanisms involved. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 56, 101508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101508

Bowling, N. A., & Beehr, T. A. (2006). Workplace harassment from the victim's perspective: A theoretical model and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 998.

Branch, S., Shallcross, L., Barker, M., Ramsay, S., & Murray, J. P. (2021). Theoretical frameworks that have explained workplace bullying: Retracing contributions across the decades. Concepts, Approaches and Methods, 87–130.

Brendgen, M., & Poulin, F. (2017). Continued bullying victimization from childhood to young adulthood: A longitudinal study of mediating and protective factors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0314-5

Brendgen, M., Vitaro, F., Ouellet-Morin, I., Dionne, G., & Boivin, M. (2021). Links between early personal characteristics, Longitudinal Profiles of Peer Victimization in School and Victimization in College or at Work. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-021-00783-3

Cole, M. S., Shipp, A. J., & Taylor, S. G. (2016). Viewing the interpersonal mistreatment literature through a temporal lens. Organizational Psychology Review, 6(3), 273–302.

Cortina, L. M. (2017). From victim precipitation to perpetrator predation: Toward a new paradigm for understanding workplace aggression. In N. A. Bowling & M. S. Hershcovis (Eds.), Research and theory on workplace aggression (pp. 121–135). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316160930.006

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children's social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 74.

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1996). Social information-processing mechanisms in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Development, 67(3), 993–1002.

Desrumaux, P., & De Chacus, S. (2007). Bullying at work: Effects of the victim's pro and antisocial behaviors and of the harassed's overvictimization on the judgments of help-giving. Studia Psychologica, 49(4), 357.

Desrumaux, P., Machado, T., Vallery, G., & Michel, L. (2016). Bullying of the manager and Employees' prosocial or antisocial behaviors: Impacts on equity, responsibility judgments, and Witnesses' help-giving. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 9(1), 44–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/ncmr.12064

Dhanani, L. Y., Main, A. M., & Pueschel, A. (2020). Do you only have yourself to blame? A meta-analytic test of the victim precipitation model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(8), 706–721.

Einarsen, S., & Nielsen, M. B. (2014). Workplace bullying as an antecedent of mental health problems: A five-year prospective and representative study. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 88(2), 131–142.

Einarsen, S., & Skogstad, A. (1996). Bullying at work: Epidemiological findings in public and private organizations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 185–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414854

Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Notelaers, G. (2009). Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the negative acts questionnaire-revised. Work and Stress, 23(1), 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370902815673

Einarsen, S. V., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., & Cooper, C. L. (2020). The concept of bullying and harassment at work: The European tradition. In S. E. Valvatne, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Theory, research and practice.

Glambek, M., Skogstad, A., & Einarsen, S. (2016). Do the bullies survive? A five-year, three-wave prospective study of indicators of expulsion in working life among perpetrators of workplace bullying. Industrial Health, 54(1), 68.

Glambek, M., Skogstad, A., & Einarsen, S. V. (2020). Does the number of perpetrators matter? An extension and re-analysis of workplace bullying as a risk factor for exclusion from working life. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 30(5), 508–515.

Glasø, L., Nielsen, M. B., & Einarsen, S. (2009). Interpersonal problems among perpetrators and targets of workplace bullying. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(6), 1316–1333.

Goodrich, B., Gabry, J., Ali, I., & Brilleman, S. (2020). Rstanarm: Bayesian applied regression modeling via Stan. R package version 2.21.1.

Gupta, P., Gupta, U., & Wadhwa, S. (2020). Known and unknown aspects of workplace bullying: A systematic review of recent literature and future research agenda. Human Resource Development Review, 19(3), 263–308.

Guy, A., Lee, K., & Wolke, D. (2017). Differences in the early stages of social information processing for adolescents involved in bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 43(6), 578–587. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21716

Hamre, K. V., Einarsen, S. V., Hoprekstad, Ø. L., Pallesen, S., Bjorvatn, B., Waage, S., Moen, B. E., & Harris, A. (2020). Accumulated long-term exposure to workplace bullying impairs psychological hardiness: A five-year longitudinal study among nurses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2587.

Hoprekstad, Ø. L., Hetland, J., Bakker, A. B., Olsen, O. K., Espevik, R., Wessel, M., & Einarsen, S. V. (2019). How long does it last? Prior victimization from workplace bullying moderates the relationship between daily exposure to negative acts and subsequent depressed mood. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2018.1564279

Hoprekstad, Ø. L., Hetland, J., Wold, B., Torp, H., & Einarsen, S. V. (2020). Exposure to bullying behaviors at work and depressive tendencies: The moderating role of victimization from bullying during adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0886260519900272.

Janoff-Bulman, R. (1989). Assumptive worlds and the stress of traumatic events: Applications of the schema construct. Social Cognition, 7(2), 113–136.

Janoff-Bulman, R. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Three explanatory models. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 30–34.

JASP Team. (2020). JASP (version 0.14.1)[computer software]. In: Amsterdam.

Jeffreys, H. (1961). Appendix B. In: Theory of Probability.

Kass, R. E., & Raftery, A. E. (1995). Bayes factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90(430), 773–795.

Lemmer, G., & Gollwitzer, M. (2017). The “true” indirect effect won't (always) stand up: When and why reverse mediation testing fails. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 69, 144–149.

León-Pérez, J. M., Escartín, J., & Giorgi, G. (2021). The presence of workplace bullying and harassment worldwide. In P. D'Cruz, E. Noronha, G. Notelaers, & C. Rayner (Eds.), Concepts, approaches and methods (pp. 55–86). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0134-6_3

Lereya, S. T., Copeland, W. E., Costello, E. J., & Wolke, D. (2015). Adult mental health consequences of peer bullying and maltreatment in childhood: Two cohorts in two countries. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(6), 524–531.

Leymann, H. (1996). The content and development of mobbing at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594329608414853

Matthiesen, S. B., & Einarsen, S. (2007). Perpetrators and targets of bullying at work: Role stress and individual differences. Violence and Victims, 22(6), 735–753.

Mikkelsen, E. G., & Einarsen, S. (2002). Basic assumptions and symptoms of post-traumatic stress among victims of bullying at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 11(1), 87–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320143000861

Mikkelsen, E. G., Hansen, Å. M., Persson, R., Byrgesen, M. F., & Hogh, A. (2020). Individual consequences of being exposed to workplace bullying. In S. V. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Developments in theory, research and practice (pp. 163–208). CRC Press.

Monks, C. P., Smith, P. K., Naylor, P., Barter, C., Ireland, J. L., & Coyne, I. (2009). Bullying in different contexts: Commonalities, differences and the role of theory. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(2), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.01.004

Mulder, J., Gu, X., Olsson-Collentine, A., Tomarken, A., Böing-Messing, F., Hoijtink, H., Meijerink, M., Williams, D. R., Menke, J., & Fox, J.-P. (2019). BFpack: Flexible Bayes factor testing of scientific theories in R. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.07728.

Muthén, B., & Asparouhov, T. (2012). Bayesian structural equation modeling: A more flexible representation of substantive theory. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 313.

Muthén, B., & Asparouhov, T. (2015). Causal effects in mediation modeling: An introduction with applications to latent variables. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22(1), 12–23.

Namie, G., & Namie, R. (2018). Risk factors for becoming a target of workplace bullying and mobbing. In M. Duffy & D. C. Yamada (Eds.), Workplace bullying and mobbing in the United States. Praeger Press.

Nielsen, M. B., & Einarsen, S. (2018). What we know, what we do not know, and what we should and could have known about workplace bullying: An overview of the literature and agenda for future research. Aggression and Violent Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.06.007

Nielsen, M. B., & Knardahl, S. (2015). Is workplace bullying related to the personality traits of victims? A two-year prospective study. Work and Stress, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2015.1032383

Nielsen, M. B., Skogstad, A., Matthiesen, S. B., Glasø, L., Aasland, M. S., Notelaers, G., & Einarsen, S. (2009). Prevalence of workplace bullying in Norway: Comparisons across time and estimation methods. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 18(1), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320801969707

Nielsen, M. B., Matthiesen, S. B., & Einarsen, S. (2010). The impact of methodological moderators on prevalence rates of workplace bullying. A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4), 955–979.

Nielsen, M. B., Notelaers, G., & Einarsen, S. (2011). Measuring exposure to workplace bullying. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Developments in theory, research, and practice (pp. 149–174). CRC Press.

Nielsen, M. B., Hetland, J., Matthiesen, S. B., & Einarsen, S. (2012). Longitudinal relationships between workplace bullying and psychological distress. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 38(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3178

Nielsen, M. B., Tangen, T., Idsoe, T., Matthiesen, S. B., & Magerøy, N. (2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder as a consequence of bullying at work and at school. A literature review and meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 21(0), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.01.001.

Nielsen, M. B., Glasø, L., & Einarsen, S. (2017). Exposure to workplace harassment and the five factor model of personality: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 195–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.08.015

Nielsen, M. B., Notelaers, G., & Einarsen, S. V. (2020). Methodological issues in the measurement of workplace bullying. Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Theory, Research and Practice, 235.

Notelaers, G., & Van der Heijden, B. I. J. M. (2021). Construct validity in workplace bullying and harassment research. In P. D'Cruz, E. Noronha, G. Notelaers, & C. Rayner (Eds.), Concepts, approaches and methods (pp. 369–424). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0134-6_11

Notelaers, G., Einarsen, S., De Witte, H., & Vermunt, J. K. (2006). Measuring exposure to bullying at work: The validity and advantages of the latent class cluster approach. Work and Stress, 20(4), 289–302.