Abstract

This paper investigates the structure of the Post-Critical Belief Scale (PCBS), which was designed by Hutsebaut (1996) to assess attitudes towards religion according to Wulff’s (1991) model. Existing results suggest ambiguous solutions, with two, three, or four factors, when only the four-factor solution is consistent with Wulff’s theoretical model. In the current study, we examined whether this hypothesized model indeed would be reflected in the data, when the more appropriate, newly-developed, Set-Exploratory Structural Equation modeling (Set-ESEM) is applied. The study was carried out on a sample of 952 participants. The results of the Set-ESEM modeling provided evidence for the good fit of the four-factor structure. Nevertheless, we also identified some shortcomings of the measure and identified items which may be removed in order to increase measurement precision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Structure of Attitudes Towards Religion Measured by the Post-Critical Belief Scale

One of the most frequently used models of attitudes towards religion was proposed by Wulff (1991) comprising four basic attitudes. To measure these attitudes, Hutsebaut (1996) developed the Post-Critical Belief Scale (PCBS). However, there have been problems with the scale’s structure since its initial development, with various empirical studies reporting an inconsistent structure. Despite the fact that a four-factor solution is expected, some studies have revealed two factors, and others sometimes three or four factors. It seems that one of the reasons for the inconsistencies may have been the use of different statistical methods, not matched to the model. The aim of this study was to test the structure of the PCBS using statistical methods appropriate to the model. This is the first time such a structural analyses of the PCBS has been performed.

Wulff’s Model

Wulff (1991) summarized many different variables describing religiosity, especially religious attitudes, in the model of four attitudes toward religion, described by two dimensions. These dimensions are: (a) Inclusion vs. Exclusion of Transcendence (Does the person believe in God or not? Does God’s transcendence fit into the structure of the person’s philosophy of life or not?) and (b) Literal vs. Symbolic referring to the way in which a person interprets religious content (How do people believe? Are religious contents, expressions, and symbols interpreted literally or symbolically?). The combination of these dimensions results in four types of attitudes towards religion interpretation (Wulff, 1991): Literal Affirmation (literal inclusion of Transcendence), Literal Disaffirmation (literal exclusion of Transcendence), Reductive Interpretation (symbolic exclusion of Transcendence), and Restorative (symbolic inclusion of Transcendence). Dimensions and attitudes are presented in Fig. 1. The operationalization of the four attitudes was proposed by Hutsebaut (1996) and Duriez et al. (2000) who used slightly different labels; therefore, in Fig. 1 Hutsebaut’s operationalization is presented in gray and in the description below it is presented in parentheses.

Integration of Hutsebaut’s Dimensions of Religiosity in Wulff’s Model (Fontaine et al., 2003). Note. Hutsebaut’s operationalization are presented in grey

Literal Affirmation (labeled Orthodoxy in Hutsebaut’s operationalization) was defined as recognizing the realness of a religious object and its literal interpretation. An example of this kind of attitude is religious fundamentalism, and an example item to measure this attitude is: ‘I think that Bible stories should be taken literally, as they are written.’ Literal Disaffirmation (labeled External Critique in Hutsebaut’s operationalization) is a position in which religious assertions are understood literally but their veracity is denied. This attitude usually involves exclusive acceptance of assertions based on the results provided by science and meeting its rational criteria, as in the antireligious orientation or atheism. An example item is: ‘Faith is an expression of a weak personality.’ Reductive Interpretation (labeled Relativism in Hutsebaut’s operationalization) refers to an attitude of rejecting the realness of the religious object while giving a privileged position to the hidden, symbolic meaning of a religious myth or ritual. Like Literal Disaffirmation, Reductive Interpretation denies the realness of transcendent referents of religious language and practices. An example construct that falls within this quadrant is the seeking orientation, and an example item is: ‘God grows together with the history of humanity and, therefore, is changeable’. Restorative Interpretation (labeled Second Naiveté in Hutsebaut’s operationalization) is an attitude in which one recognizes that transcendent reality is real but avoids identifying the religious objects in it in an unambiguous and literal way. Instead, one seeks the symbolic meaning that these objects carry. An example item is: ‘The Bible holds a deeper truth which can only be revealed by personal reflection’ (Hutsebaut, 1996; Wulff, 1991).

Wulff’s model is clearly inspired by the thought of Ricoeur (1978), who believed that religious faith in the modern era (in which the phenomenon of atheism and the progressive secularization of societies are common) takes the form of rational interpretations and reinterpretations. Wullf called this approach by Ricouer the post-critical approach and is understood as a kind of reconstruction of religion after considerable criticism of religion from scientific standpoints in the twentieth century (Hutsebaut, 1996). In his model, Wulff also uses the term introduced by Ricoeur (though not created by him) “second naiveté”. Second naiveté is the result of the process of symbolic thinking, which is carried out taking into account historical criticism and the context of possible meanings that enable critical question to be asked about religion and the meaning of human existence while allowing inclusion of Transcendence (Hutsebaut, 1996; Wallace, 1995).

Problems with the Structure of Attitudes Towards Religion in Previous Studies

The attitudes toward religion distinguished by Wulff (1991) are measured using the Post-Critical Belief Scale (PCBS), developed by Hutsebaut (1996).

Also the name of Hutsebaut’s (1996) scale - the Post-Critical Belief Scale (PCBS) and the names of differentiated variables refer to Ricouer’s above-mentioned concept. The External Critique rejects the possibility of believing due to skepticism and the assumption that it is impossible to understand the symbolic language of images contained in, e.g., images from the Bible. Criticism and outward standing remain the only way of looking at religion for these people. Only when this totally critical approach gives way to an approach that searches but does not reject the complex biblical language and message it contains, does the process of re-construction of religion (re-meaning – a post-critical stage) that characterizes people from Second Naiveté begin. In Orthodoxy, people avoid any criticism of the religious message, sticking to established patterns, while in Relativism they are characterized by a post-critical approach, but somewhat above the established doctrine /religion, in which relativism to the doctrine and exploration dominate.

Hutsebaut (1996) began by formulating 24 items that were supposed to measure the four attitudes distinguished in Wulff’s (1991) model. Factor analysis revealed, however, that the scale measured only three variables: Orthodoxy, Historical Relativism, and External Critique. Therefore, Duriez et al. (2000) undertook further work aimed at improving the scale and refining the constructs to operationalize Wulff’s model (Wulff, 1991). The outcome of their work was a 33-item scale measuring four variables corresponding to all attitudes included in that model (1991).

Statistical analyses on the PCBS data have yielded inconsistent conclusions about its internal structure, and this may be related to limitations in the types of statistics used. The internal structure of the PCBS has usually been investigated using the following methods: factor analysis (FA), principal component analysis (PCA), multidimensional scaling (MDS), and clusterwise simultaneous component analysis equal cross-product (SCA-ECP). The results obtained in these analyses proved to be ambiguous. FA and SCA-ECP showed the existence of three factors (Hutsebaut, 1996; Krysinska et al., 2014), while PCA yielded two factors, with the Inclusion vs. Exclusion of Transcendence factor being better fitted in some samples than Literal vs. Symbolic (Bartczuk et al., 2013; Cortés Gómez et al., 2016; Duriez et al., 2003). MDS analyses, in contrast, showed the existence of four factors (Aguilar-Vafaie & Moghanloo, 2008; Bartczuk et al., 2011; Bartczuk et al., 2013; Cortés Gómez et al., 2016; Duriez et al., 2003; Duriez et al., 2000; Duriez et al., 2005; Fontaine et al., 2003).

A summary of the methods and results is provided in Table 4 in Appendix. More specifically, the initial study based on exploratory factor analysis (EFA) revealed three factors: Orthodoxy, Historical Relativism, and External Critique (Hutsebaut, 1996). Further reanalysis led to different conclusions, suggesting that Historical Relativism belongs not only to Inclusion but also to the Exclusion of Transcendence (Duriez et al., 2000). This led to the distinction of two symbolic dimensions: Second Naiveté (Inclusion of Transcendence) and Relativism (Exclusion of Transcendence). The structure of the PCBS can therefore be organized into two bipolar dimensions: Inclusion vs Exclusion of Transcendence and Literal vs Symbolic, resulting in four factors corresponding to the four attitudes towards religion (Wulff, 1991).

However, previous research was burdened with certain limitations. The majority of studies (e.g., Bartczuk et al., 2013; Cortés Gómez et al., 2016; Duriez et al., 2000; Duriez et al., 2005; Fontaine et al., 2003) employed principal component analysis (PCA), whose main aim is to reduce observable data into components. While this approach is conceptually similar to factor analysis (in terms of grouping items into components) and might be useful in analyzing items regarding observable expressions (e.g., behaviors), it is not suited to lead to conclusions about underlying non-observable latent constructs (i.e., factors; Fabrigar et al., 1999; Gorsuch, 1990). Usually, two components were extracted: Inclusion vs. Exclusion of Transcendence and Literal vs. Symbolic. However, this extraction was frequently based on the inspection of the scree plot (e.g., Bartczuk et al., 2011; Duriez et al., 2000), which is burdened with the subjectivity of interpretation (Ruscio & Roche, 2012; Zwick & Velicer, 1986). These components were typically seen as corresponding to the dimensions identified in multidimensional scaling (MDS). In MDS, four variables were usually extracted on two-dimensional space (e.g., Aguilar-Vafaie & Moghanloo, 2008; Cortés Gómez et al., 2016; Duriez et al., 2000). Two of them involved the Inclusion of Transcendence, namely: Orthodoxy (literal) and Second Naiveté (symbolic), and two involved the Exclusion of Transcendence: External Critique (literal) and Relativism (symbolic). It should be noted, however, that MDS is a statistical technique which makes it possible to explore the degree of similarity between variables in terms of their distance and closeness (Davison & Sireci, 2000) rather than to draw conclusions about any underlying latent constructs. Therefore, it is a rather sophisticated ‘eyeballing’ procedure (Tracey, 2000). To sum up, there are many equivocal results in the literature which are partially derived from the use of various analytical procedures (i.e., two factors in PCA; three factors in EFA and SCA-ECP, and four factors in MDS). These analyses, however, did not take into account the specificity of the model, which distinguishes two dimensions and four types of attitudes as combinations of dimensions. To analyze models with a complex structure, there are, however, more advanced techniques such as different variants of the Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling (ESEM; Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009), which benefits over traditional methods will be discussed in the Methods section.

The main goal of the current study was to analyze the structure of the PCBS by using current psychometric methods developed to test more complicated structures like Wulff’s (1991) model. By using such a method we expected to find a four-factor structure as predicted by the theoretical model.

Method

Measure

Attitudes towards religion were measured using a Polish adaptation of the Post-Critical Belief Scale (Bartczuk et al., 2011) developed by Hutsebaut (1996). We used the 33-item version, measuring four attitudes towards religion: Orthodoxy, External Critique, Relativism, and Second Naiveté. Responses were indicated on a 7-pt scale from 1 = strongly agree to 7 = strongly disagree.

Participants and Procedure

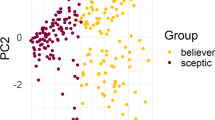

All participants were Caucasians of Polish nationality. Catholicism is still a predominant religion in Poland – according to the Pew Resarch Center (2018) findings on the significance of religion in Central and Eastern Europe, 96% of Poles were raised as Christian and 92% still identify as such. Given the prevalence of Catholicism in Poland, it is fair to suggest that respondents either were Catholics or at least had some knowledge about the doctrine and customs of the Catholic Church. To determine the required sample size, we relied on a rule of thumb stating that the item to participant ratio should ideally be over 20:1 (Costello & Osborne, 2005) a ratio of 20 respondents per one item (i.e., 20:1) guarantees adequate power, resulting in a minimum sample size of 660. The study included 952 participants (item to participant ratio = 28.85) aged 19 to 32 (M = 21.65 years, SD = 2.04; 459 women and 493 men). They were students of various majors and various types of higher education institutions. The participants completed a personal demographic survey, the questionnaire, and tests, including the PCBS. Each participant was provided with a clear instructions, so the questionnaire was completed under the same conditions for all participants. Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. All statistical scripts and raw data are available at the OSF project site at https://osf.io/83a6n/?view_only=2388524aa8cc4588b388c3649b1d026f

Statistical Analyses

Two forms of factor analysis are usually performed and reported in the literature: confirmatory (CFA) and exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The difference between them lies in the fact that while the former allows for testing models specified a priori, the latter does not impose any restrictions on what the measurement model should be like. Both statistical procedures have their pros and cons. For example, CFA is frequently criticized for being overly restrictive, as it assumes that each item loads on one and only one factor. EFA, by contrast, is a purely exploratory technique, which does not allow for statistically testing whether the proposed model fits the actual data and lacks the multiple advances made in CFA models (e.g., tests of measurement invariance, differential item functioning, and control for measurement error structures; Marsh et al., 2013). To address these problems, a new statistical procedure was developed, combining the rigor of CFA and the flexibility of EFA, namely, exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM; Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009). Like CFA, ESEM allows for testing models specified a priori while retaining the possibility for cross-loadings to emerge (Marsh et al., 2014). This is achieved thanks to the specially designed target rotation, which targets the factor loadings of the selected items to be as close to zero as possible. It has to be acknowledged that in large and complex models ESEM might lack parsimony and might confound constructs that need to be kept separate in relation to theory. To address this problem, Set-ESEM was introduced to overcome limitations found in ESEM and CFA (Marsh et al., 2020). In Set-ESEM, two or more sets of constructs are modeled within a single model, however cross-loadings are allowed to occur within the same set but are constrained to be zero across different sets. To better illustrate the differences between ESEM, Set-ESEM, and CFA, we provide their graphical illustrations in Fig. 2.

Regarding the PCBS, Set-ESEM seems to most adequately represent the hypothesized structure. Given the fact that the traditional EFA was unable to differentiate the symbolic factors of Second Naiveté and Relativism, we propose to model two sets of constructs, representing Inclusion of Transcendence (i.e., Orthodoxy and Second Naiveté) and Exclusion of Transcendence (i.e., External Critique and Relativism). In this manner, cross-loadings are permissible, for example, between Orthodoxy and Second Naiveté, but they are constrained to be zero, for example, between Orthodoxy and External Critique. Set-ESEM therefore offers an advance over what other statistical procedures had to offer and seems to best theoretically capture the hypothesized structure of the PCBS.

As all other models in a structural equation modeling framework, Set-ESEM is evaluated in terms of how the specified model fits the data better than the null model (i.e., a model where all coefficients are freely estimated). Such comparison is done by means of approximate fit indices. Generally, there are three recommended fit indices: comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). The usual cut-off differentiating whether the model is well fitted or not is.90 (or more) for CFI and .08 (or less) for RMSEA and SRMR (Byrne, 1994; Hu & Bentler, 1999). All analyzed models were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation with robust means and standard errors. The analyses were carried out in Mplus v. 7.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012).

Results

The descriptive statistics, internal consistencies, and scale intercorrelations are provided in Table 1.

The analyzed Set-ESEM model reached the following fit indices: χ2(460) = 1338.02, p < .001; CFI = .893, RMSEA = .045, 90% CI [.042, .048]; SRMR = .051. We also analyzed two additional solutions: a fully constrained CFA model and a regular ESEM model. The fit indices of the CFA model suggested poor fit, χ2(489) = 2274.43, p < .001; CFI = .783, RMSEA = .062, 90% CI [.059, .065]; SRMR = .089. With regard to the regular ESEM model (χ2(402) = 861.49; p < .001; CFI = .944, RMSEA = .035[90% CI, .031, .038]; SRMR = .027), it was considerably better fitted than the Set-ESEM; however, we identified a wide range of cross-loadings that made the interpretation of the model troublesome (e.g., Relativism items cross-loaded on Second Naiveté—see supplementary materials presented on the OSF project website). Thus, the Set-ESEM model appears to be the most parsimonious of all analyzed models. The standardized factor loadings of the Set-ESEM solution are presented in Table 2.

Within-set factors correlated positively with each other—that is, Orthodoxy correlated with Second Naiveté (ρ = .48, p < .001) and External Critique correlated with Relativism (ρ = .39, p < .001). Orthodoxy was found to be negatively related to External Critique (ρ = −.33, p < .001) and Relativism (ρ = −.32, p < .001). Second Naiveté was negatively related to External Critique (ρ = −.78, p < .001) but positively related to Relativism (ρ = .16, p = .015). The strength of the factor loadings was mostly adequate on the respective assumed factors. Nevertheless, there were a few exceptions. Within the Inclusion of Transcendence factors, three items cross-loaded (i.e., items 4, 7 and 25) and two had low loadings (i.e., items 12 and 16). Within Exclusion of Transcendence three items (i.e., items 23, 28 and 29) cross-loaded and two items (i.e., items 9 and 13) had similar loadings on both factors.

We tested whether the exclusion of all these items changed the results; the results are presented in Table 3. The model fit remained similarly high (χ2(205) = 712.79, p < .001; CFI = .903, RMSEA = .051, 90% CI [.047, .055], SRMR = .050), the factor loadings were similar, and the correlations between the factors remained nearly the same. Thus, while the inclusion of these items does not seem to influence the PBCS structure to a significant extent, in order to improve measurement precision, one might consider their removal when calculating composite scores.

Discussion

As discussed above, the use of many different and not necessarily appropriate statistical methods led to the accumulation of ambiguous research results regarding the structure of PCBS. The main problem concerned the number of factors that were distinguished ranging from two, or three (structures inconsistent with Wulff’s (1991) model), to four (the structure consistent with Wulff’s model). In order for the operationalization by Hutsebaut (1996) to accurately reflect Wulff’s model, four attitudes mentioned in the text are needed. Although the literature on the subject reports the four-factor structure of PCBS (e.g., Aguilar-Vafaie & Moghanloo, 2008; Cortés Gómez et al., 2016; Duriez et al., 2000), there were also studies that indicated the structure of two- (e.g., Duriez et al., 2000) or three-factors (e.g, Krysinska et al., 2014), which introduces ambiguity regarding the usefulness of the scale as the operationalization of the Wulff's (1991) model. However, in this study we made use of a newly developed statistical method more appropriate for this type of model (i.e., Set-ESEM), which confirmed the four-factor structure as proposed by Wulff (1991). The use of the proposed statistical methods sets the further direction of research on the four-factor solution of the PCBS scale in Polish conditions. However, the wording of a few items was still problematic given the fact that they cross-loaded on other factors or had low loadings on their expected factor.

Namely, Inclusion of Transcendence, had items with significant loadings on two factors (i.e., items 4, 7, and 25). The weakness of item 7 stems from the fact that an answer affirming its content is equally significant for people with an attitude of Orthodoxy and for those with an attitude of Second Naiveté. The second part of the item refers to a dogma of the Catholic faith—the virgin birth of Jesus, which is presented in the first part of the item as opposed to the principle that this is incompatible with modern rationality. Thus, the recognition of the dogma as incompatible with modern rationality indicates symbolic processing of religious contents. It seems, however, that the content of the item refers to a greater extent to the acceptance of the religious doctrine (and this is how the item was actually understood by the participants), which is both literally and symbolically significant to religious people. While accepting the Catholic doctrine, one may still be guided in one’s actions by open-minded thinking (characteristic of Second Naiveté), taking various points of view into account and showing respect for different views, as expected by Wulff (1991). It is therefore not surprising that item 7 loads on Second Naiveté and on Orthodoxy.

Items 4 and 25 were two other weak items with significant loadings on two factors. Again, the contents of these items are important both for Orthodoxy and for Second Naiveté. Although the authors’ intention was for the items to measure literalness in interpreting religious contents (Orthodoxy)—as shown, for instance, by the words that “God. .. is immutable” (item 4), or by the clarification of item 25, which states that “Bible stories should be taken literally,” through adding “as they are written” at the end—they may be understood, like item 7, as consistent with the doctrine (and thus significant for both types of religiosity). In item 4, God in the theological sense is indeed unchangeable. In item 25, although the literal understanding of biblical stories is stressed, (i.e., Orthodoxy), the item is indirectly referring to the deposit of faith preserved in the canon of Scripture and handed down in an unchanged form (“as they are written”) over the centuries in the Catholic Church.

It seems that the weak loadings in the case of items 12 and 16 stem from respondents’ failure to understand them (generally, PCBS items seem to be difficult to understand). A similar problem was signaled by Pollefeyt and Bouwens (2010) in a sample of students from Catholic schools in Australia. In both items, theological issues are raised including ones that require some degree of familiarity with biblical science, for example the history of some biblical stories. This is not common knowledge, which means participants may not have had the knowledge required to properly understand these items.

In the case of the Exclusion of Transcendence items, the problem with the low loadings of items 9 and 13 can be explained as stemming from the fact that they contain words strictly associated with religiosity (understood as a system and structure), such as “religion” or “God,” which may have been incomprehensible or unacceptable for those respondents who were not religious but, for instance, consider themselves spiritual people unaffiliated with the visible structure of a church or denomination. It seems that a similar explanation can be offered to account for the problem with item 29, which is an Orthodoxy item but loads on the Relativism factor: “In order to fully understand what religion is all about, you have to be an outsider.” For those who consider themselves seekers (according to Wulff’s (1991) model, such individuals fall into the Relativism quadrant), this distance from “systemic” religion can be explained, for example, by a spiritual quest unrelated to a specific form of belief. Thus religion as a structure is rejected, but not transcendence. Additionally, the above items assume that a person at least “knows” what religion or spirituality is (in the sense that they for example used to be religious or are open to spirituality). However, this may be challenging for people falling into the External Critique quadrant, who have no experience with religion or spirituality. Indeed, Krysinska et al. (2014) reported that some of their respondents had difficulties understanding and accepting items that concerned the Catholic doctrine.

The weak loadings of items 23 and 28 (included in Relativism) on External Critique can be explained as resulting from the fact that even though individuals reject transcendent reality, in the Polish sample they do not do this strongly, leaving some room for doubt (hence the Relativism items).

To sum up, systematic problems with several items have been identified concerning issues such as: simultaneous importance of an item’s contents for two types of religiosity; believers’ failure to understand the contents of items (problems with excessively difficult theological language); failure to understand and accept the items concerning “systemic religiosity” in the case of individuals who consider themselves spiritual but are not affiliated with any denomination. The results of the analyses performed after removing the problematic items from the PCBS indicate that, for a greater precision of measurement, it is recommendable to use the short version.

It seems that the problematic items are problematic beyond the Polish version of the PCBS, but this issue requires further research. The proposal of new more appropriate analytical tools presented in this article does not preclude the existence of non-statistical shortcomings of the PCBS, such as those mentioned by Krysinska et al. (2014).

However, it should be stressed that, in a large measure, these shortcomings may concern the operationalization rather than Wullf’s (1991) model itself. For this reason, taking the results of this study into consideration and using a short version of the scale or modifying the problematic items may help to overcome the problems with the structure of attitudes towards religion that are reported in the literature.

Set-ESEM used in this article turns out to be more useful for studying and explaining the factor structure of PCBS than previously used methods, such as: PCA, EFA, SCA-ECP and MDS. The usefulness of Set-ESEM in the field of the psychology of religion seems promising especially where new sophisticated, multifactorial models are created, in which attempts are made to integrate the existing knowledge or to analyse and explain the relationships between many factors.

Limitations and Future Research

This work has some limitations which must be taken into account. The study was conducted in a Polish sample, so the conclusions may be limited to such populations where Catholicism is the dominant religion. Another limitation is the specificity of emerging adulthood (Smith & Snell, 2009) to which most of the respondents belonged. Further research should replicate these findings in other countries and age groups.

Based on the obtained results one can conclude that the PCBS scale can be treated as a sound operationalization of Wulff’s model in predominantly Christian samples, but in the future it is worthwhile to undertake work on revising some troublesome items. Another issue is the theoretical foundation of the model. In further theorizing it is worth considering whether the concept of post-critical beliefs and basic dimensions for describing the attitudes are adequate to analyze contemporary religiosity (e.g., Krysinska et al., 2014). Even if Wullf’s model is operationalized correctly, new models describing individual differences in religiosity may be welcome.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the OSF repository, https://osf.io/83a6n/?view_only=2388524aa8cc4588b388c3649b1d026f

References

Aguilar-Vafaie, M. E., & Moghanloo, M. (2008). Domain and facet personality correlates of religiosity among Iranian college students. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 11(5), 461–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670701539114

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2009). Exploratory structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 16(3), 397–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510903008204

Bartczuk, R. P., Wiechetek, M. P., & Zarzycka, B. (2011). Skala Przekonań Postkrytycznych D. Hutsebauta [The post-critical belief scale by D. Hutsebaut]. In M. Jarosz (Ed.), Psychologiczny pomiar religijności [psychological measurement of religiosity] (pp. 201–229). Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL.

Bartczuk, R. P., Zarzycka, B., & Wiechetek, M. P. (2013). Struktura wewnętrzna polskiej adaptacji skali przekonań postkrytycznych [The internal structure of Polish adaptation the post-critical belief scale]. Roczniki Psychologiczne, 16(3), 539–561.

Byrne, B. M. (1994). Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/windows: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Sage.

Cortés Gómez, C. E., Jimenez-Leal, W., & Finck, C. (2016). Effects of secularisation on the psychometric properties of the post critical belief scale. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 19(8), 868–882. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2016.1229288

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10, 7. https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868

Davison, M. L., & Sireci, S. G. (2000). Multidimensional scaling. In Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling (pp. 323–352). Elsevier.

Duriez, B., Fontaine, J. R., & Hutsebaut, D. (2000). A further elaboration of the post-critical belief scale: Evidence for the existence of four different approaches to religion in Flanders-Belgium. Psychologica Belgica, 40(3), 153–182.

Duriez, B., Appel, C., & Hutsebaut, D. (2003). The German post-critical belief scale: Internal and external validity. Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie, 34(4), 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1024/0044-3514.34.4.219

Duriez, B., Soenens, B., & Hutsebaut, D. (2005). Introducing the shortened post-critical belief scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(4), 851–857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.06.009

Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 272–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.3.272

Fontaine, J. R., Duriez, B., Luyten, P., & Hutsebaut, D. (2003). The internal structure of the post-critical belief scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(3), 501–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00213-1

Gorsuch, R. L. (1990). Common factor analysis versus component analysis: Some well and little known facts. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25(1), 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2501_3

Hu, L. t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hutsebaut, D. (1996). Post-critical belief a new approach to the religious attitude problem. Journal of Empirical Theology, 9(2), 48–66. https://doi.org/10.1163/157092596X00132

Krysinska, K., De Roover, K., Bouwens, J., Ceulemans, E., Corveleyn, J., Dezutter, J., Duriez, B., Hutsebaut, D., & Pollefeyt, D. (2014). Measuring religious attitudes in secularized Western European context: A psychometric analysis of the post-critical belief scale. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 24(4), 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2013.879429

Mariański, J. (2011). Tendencje rozwojowe w polskim katolicyzmie–diagnoza i prognoza [The developmental tendencies in the Polish catholicism. The diagnosis and the prognosis]. Teologia Praktyczna, 12, 7–24.

Marsh, H. W., Nagengast, B., & Morin, A. J. (2013). Measurement invariance of big-five factors over the life span: ESEM tests of gender, age, plasticity, maturity, and la dolce vita effects. Developmental Psychology, 49(6), 1194–1218. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026913

Marsh, H. W., Morin, A. J., Parker, P. D., & Kaur, G. (2014). Exploratory structural equation modeling: An integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 85–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153700

Marsh, H. W., Guo, J., Dicke, T., Parker, P. D., & Craven, R. G. (2020). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM), and set-ESEM: Optimal balance between goodness of fit and parsimony. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 55(1), 102–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1602503

Muñoz-García, A., & Saroglou, V. (2008). Believing literally versus symbolically: Values and personality correlates among Spanish students. Journal of Beliefs and Values, 29, 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13617670802465755

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables; user's guide; [version 7]. Muthén et Muthén.

Pew Resarch Center. (2018). Eastern and Western Europeans differ on importance of religion, views of minorities and key social issues. https://www.pewforum.org/2018/10/29/eastern-and-western-europeans-differ-on-importance-of-religion-views-of-minorities-and-key-social-issues/

Pollefeyt, D., & Bouwens, J. (2010). Framing the identity of Catholic schools: Empirical methodology for quantitative research on the Catholic identity of an education institute. International Studies in Catholic Education, 2(2), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/19422539.2010.504034

Ricoeur, P. (1978). The critique of religion. In Ch. E. Reagen, D. Stewart (Eds.), The philosophy of Paul Ricoeur. An anthology of his work (pp. 213–222). Beacon.

Ruscio, J., & Roche, B. (2012). Determining the number of factors to retain in an exploratory factor analysis using comparison data of known factorial structure. Psychological Assessment, 24(2), 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025697

Smith, C., & Snell, P. (2009). Souls in transition: The religious and spiritual lives of emerging adults. Oxford University Press.

Tracey, T. J. (2000). Analysis of circumplex models. In H. E. A. Tinsley & S. D. Brown (Eds.), Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling (pp. 641–664). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012691360-6/50023-9

Wallace, M. I. (1995). The second naiveté: Barth, Ricoeur, and the new Yale theology. Mercer University Press.

Wulff, D. (1991). Psychology of religion: Classic and contemporary views. Wiley.

Zwick, W. R., & Velicer, W. F. (1986). Comparison of five rules for determining the number of components to retain. Psychological Bulletin, 99(3), 432–442.

Funding

The work of Radosław Rogoza was supported by the Foundation for Polish Science (FNP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was performed in line with the principles of ethic in Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose. The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Szydłowski, P., Rogoza, R. & Cieciuch, J. The structure of the attitudes toward religion as measured by the Post-Critical Belief Scale: A structural modelling approach. Curr Psychol 42, 10792–10803 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02367-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02367-2