Abstract

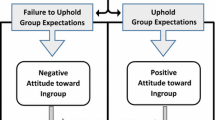

The social identity tradition has not reached a consensus regarding the question of whether identifying with an ingroup directly leads to ingroup bias, or whether this association may be moderated by group norms. One previous study (Jetten, Spears, & Manstead, 1997) showed that an ingroup norm of fairness as opposed to differentiation seems to moderate this link between identification and ingroup bias. The present research aims to examine the extent to which real-life group members (Kurds and Turks) with a history of conflict engage in ingroup bias as a function of their level of identification when group norms prescribe favoritism or equality. In Study 1, Kurdish and Turkish participants report their ingroup norm (egalitarianism or favoritism) and allocate a fixed amount of funds between Kurds and Turks in a hypothetical situation. The results show a significant interaction between social identification and group norm on ingroup bias. Accordingly, ingroup bias increases with the strength of identification when the norm is favoritism; however, there is no relationship when the norm is egalitarianism. Study 2 manipulates the ingroup norm for Kurdish and Turkish participants in the same hypothetical context. This time, the interaction is marginally significant but in a similar direction, where stronger identification leads to higher ingroup bias in the favoritism norm condition, yet this effect disappears in the egalitarianism norm condition. These findings extend the literature on the role of norms in intergroup relations, emphasizing the important role of egalitarian norms in reducing ingroup bias even in real-life conflict-ridden contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data and the appendices for both studies are available on https://osf.io/wq4jx/?view_only=1cce855bf9584ddfa5ba43a5f35e9502

Notes

Due to a weak but significant correlation between age and ingroup bias for the favoritism norm condition, we repeated the analysis with age as a covariate but found no difference in results. Hence we report the results without age as a covariate for consistency purposes.

References

Aberson, C. L., Healy, M., & Romero, V. (2000). Ingroup bias and self-esteem: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(2), 157–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_04.

Baser, B., & Ozerdem, A. (2019). Conflict transformation and asymmetric conflicts: A critique of the failed Turkish-Kurdish peace process. Terrorism and Political Violence, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2019.1657844.

Brown, R., & Pehrson, S. (2019). Group processes: Dynamics within and between groups. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118719244.

Cingöz-Ulu, B. & Lalonde, R. N. (2008). Ingroup identification and intergroup differentiation: A meta-analytic review. 7th biennial Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, , U.S.A.

Cohen, J. (1978). Conformity and norm formation in small groups. Pacific Sociological Review, 21(4), 441–466. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388695.

Çoksan, S. (2019). İç grubu kayırma ile iç ve dış gruba eşit davranmanın nedensel atıfları [Causal attributions of ingroup favoritism and equal allocation between in and outgroup]. Nesne, 7(14), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.7816/nesne-07-14-06.

Cooley, S., & Killen, M. (2015). Children's evaluations of resource allocation in the context of group norms. Developmental Psychology, 51(4), 554–563. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038796.

De Vries, R. E. (2003). Self, ingroup, and outgroup evaluation: Bond or breach? European Journal of Social Psychology, 33(5), 609–621. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.173.

Deutsch, M. (1985). Distributive justice: A social-psychological perspective. Yale University Press.

Hall, N. R., & Crisp, R. J. (2008). Assimilation and contrast to group primes: The moderating role of ingroup identification. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(2), 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2007.07.007.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (second ed.). The Guilford Press.

Henderson-King, E., Henderson-King, D., Zhermer, N., Posokhova, S., & Chiker, V. (1997). Ingroup favoritism and perceived similarity: A look at Russians’ perceptions in the post-soviet era. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(10), 1013–1021. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672972310002.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature, 466(7302), 29–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/466029a.

Hinkle, S., & Brown, R. (1990). Intergroup comparisons and social identity: Some links and lacunae. In D. Abrams & M. A. Hogg (Eds.), Social identity theory: Constructive and critical advances. Harvers-te-Wheatsheaf.

Hogg M. A. (2016). Social identity theory. In S.McKeown, R. Haji, & N. Ferguson (Eds.), Understanding peace and conflict through social identity theory. Peace Psychology Book Series. Springer.

Jarymowicz, M. (1998). Self-we-others schemata and social identifications. In S. Worchel, J. F. Morales, D. Páez, & J.-C. Deschamps (Eds.), Social identity: International perspectives (pp. 44–52). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446279205.n4.

Jetten, J., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. (1996). Intergroup norms and intergroup discrimination: Distinctive self-categorization and social identity effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(6), 1222–1233. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.6.1222.

Jetten, J., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. (1997). Strength of identification and intergroup differentiation: The influence of group norms. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27(5), 603–609. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-0992(199709/10)27:5<603::aid-ejsp816>3.3.co;2-2.

Jetten, J., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. R. (1999). Group distinctiveness and intergroup discrimination. In N. Ellemers, R. Spears, & B. Doosje (Eds.), Social identity: Context, commitment, content (pp. 107–126). Blackwell Science.

Jetten, J., Spears, R., & Postmes, T. (2004). Intergroup distinctiveness and differentiation: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(6), 862–879. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.6.862.

Kelly, C. (1993). Group identification, intergroup perception, and collective action. European Review of Social Psychology, 4(1), 59–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779343000022.

Kenworthy, J. B., Barden, M. A., Diamond, S., & Carmen, A. (2011). Ingroup identification as a moderator of racial bias in a shoot–no shoot decision task. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14(3), 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430210392932.

Ma, W., & Karasawa, M. (2006). Group inclusiveness, group identification, and intergroup attributional bias. Psychologia, 49(4), 278–290. https://doi.org/10.2117/psysoc.2006.278.

McGarty, C. (2001). Social identity theory does not maintain that identification produces bias, and self-categorization theory does not maintain that salience is identification: Two comments on Mummendey, Klink, and Brown. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(2), 173–176. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164777.

Moscovici, S. (1974). Social influence I: Conformity and social control. In C. Nemeth (Ed.), Social psychology: Classic and contemporary integrations (pp. 179–216). Rand McNally.

Mummendey, A., Klink, A., & Brown, R. (2001). Nationalism and patriotism: National identification and outgroup rejection. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(2), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601164740.

Noel, J. G., Wann, D. L., & Branscombe, N. R. (1995). Peripheral ingroup membership status and public negativity toward outgroups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(1), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.1.127.

Perreault, S., & Bourhis, R. Y. (1999). Ethnocentrism, social identification, and discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(1), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299025001008.

Salmivalli, C., & Voeten, M. (2004). Connections between attitudes, group norms, and behaviour in bullying situations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(3), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000488.

Scheepers, D., Spears, R., Doosje, B., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2006). Diversity in ingroup bias: Structural factors, situational features, and social functions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(6), 944–960. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.6.944.

Sherif, M. (1936). The psychology of social norms. Harper.

Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., & Mitchell, M. (1994). Ingroup identification, social dominance orientation, and differential intergroup social allocation. The Journal of Social Psychology, 134(2), 151–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1994.9711378.

Smith, J. R., & Louis, W. R. (2009). Group norms and the attitude–behaviour relationship. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00161.x.

Spears, R. (2007). Ingroup–outgroup bias. In R. F. Baumeister, & K. D. Vohs (Eds.), Encyclopedia of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 484–485). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412956253.n286.

Spears, R., Doosje, B., & Ellemers, N. (1999). Commitment and the context of social perception. In N. Ellemers, R. Spears, & B. Doosje (Eds.), Social identity: Context, commitment, content (pp. 59–83). Blackwell Science.

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups & social categories: Studies in social psychology. Cambridge University Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co..

Terry, D. J., & Hogg, M. A. (1996). Group norms and the attitude-behavior relationship: A role for group identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(8), 776–793. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296228002.

Tropp, L. R., & Wright, S. C. (2001). Ingroup identification as the inclusion of ingroup in the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(5), 585–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201275007.

Turner, J. C. (1999). Some current issues in research on social identity and self-categorization theories. In N. Ellemers, R. Spears, & B. Doosje (Eds.), Social identity: Context, commitment, and content (pp. 6–35). Blackwell Science.

Turner, J. C., & Onorato, R. S. (1999). Social identity, personality, and the self-concept: A self-categorizing perspective. In T. R. Tyler, R. M. Kramer, & O. P. John (Eds.), Applied social research. The psychology of the social self (pp. 11–46). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Uluğ, Ö. M., & Cohrs, J. C. (2016). An exploration of lay people’s Kurdish conflict frames in Turkey. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 22(2), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000165.

Verkuyten, M., & Nekuee, S. (1999). Ingroup bias: The effect of self-stereotyping, identification, and group threat. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(2–3), 411–418. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199903/05)29:2/3<411::AID-EJSP952>3.0.CO;2-8.

Voci, A. (2006). The link between identification and ingroup favouritism: Effects of threat to social identity and trust-related emotions. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45(2), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466605X52245.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The institutional ethics committee approved the research protocol under the 2016/01 application number.

Consent to Participate

We obtained written informed consent from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflicting Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CFA Results for Ingroup Identification Scale in Studies 1 and 2

Eight items from the Racial Identification Scale (Kenworthy et al., 2011) were adapted to Turkish by the researchers. Participants rated these items (e.g., “Being a member of my ethnicity is an important reflection of who I am”) on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .88 for Kurds and .95 for Turks. Confirmatory factor analysis verified the single factor structure of the original version of the scale (χ 2 (20) = 68.2, p < .001; CFI = .94, RMSEA = .12, 95% CI [.08, .17]), hence has acceptable validity and reliability. Each item was loaded on a factor above the minimum acceptable value. Loadings were presented in Table 3. Other fit indices, on the other hand, were presented in Table 4.

For Study 2, a confirmatory factor analysis supported the single factor structure of the original scale, as in Study 1: χ 2(20) = 110, p < .001; CFI = .90, RMSEA = .16 with 95% CI [.11, .22]. Each item was loaded on a factor above the minimum acceptable value. Loadings were presented in Table 5. Other fit indices, on the other hand, were presented in Table 6.

Appendix 2. The Fictional Backstory in Both Studies

We present you with the following story. We request that you carefully read it and make a decision afterwards.

The Iran-Azerbaijan border is a region where many textile manufacturers produce for famous readymade clothing brands and the people make a living by working in these factories. Only the people who migrated from Turkey are working in this area. In recent years, major problems have been reported between two groups on the Iran-Azerbaijan border. These groups are Turks and Kurds. The problems started due to disputes over job hunting in these factories by the Turks and Kurds. Later, the disputes came to an impasse due to the ethnicities of the groups, and the two groups came to the point of severing relations with each other. Following these problems, the living standards of both groups decreased significantly and poverty in the region increased.

You are a member of an aid association called Sahibine Yardım Ulaştırma Derneği (İSYUD; Association to Aid the Disadvantaged, AAD), which will purchase ready-to-eat food and send it to this area. The amount to be spent on food for the region will be shaped by the opinions of the association members like you.

Appendix 3. Results of the Moderation Model with Age as a Covariate

The overall model was significant, F(3,154) = 16.15, p < .001, R2 = .30. The main effect of identification (b = 7880.17, t(154) = 4.49, p < .001) and norm (b = 4665.40, t(154) = 2.88, p < .01) on ingroup bias was significant. The interaction between identification and group norm (b = 3091.68, t(154) = 1.77, p = .079, 95% CI = [−368.07, 6551.43]) and the change in R2 due to the interaction (ΔR2 = .01, F(1,154) = 3.12, p = .079) were not significant. As in the original model without covariate, stronger ingroup identification was associated with higher ingroup bias when the norm was favoritism (b = 10,971.85, t(154) = 5.20, p < .001); however, there was no effect of identification on ingroup bias when the norm was egalitarianism (b = 4784.49, t(154) = 1.71, p = .09).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Çoksan, S., Cingöz-Ulu, B. Group norms moderate the effect of identification on ingroup bias. Curr Psychol 41, 64–75 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02091-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02091-x