Abstract

Previous research has demonstrated the existence of gender and sexuality differences in attitudes toward gay people (which in this paper includes both lesbian women and gay men unless specified). However, these studies did not account for people with diverse genders and sexual orientations ascribing different meanings to their gender identification and its potential role in attitudes towards gay people. This study aimed to analyze the relationship between gender identification and attitudes toward gay people among individuals of different genders and sexual orientations. Based on data obtained from 851 Russian respondents, the study reports the exploration of the direct link between two components of gender identification and four components of attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. Results indicated that stronger gender identification, in general, was related to more negative attitudes toward both gay men and lesbians. At the same time, compared to women and bisexual respondents, this link was stronger among men and straight participants respectively. A possible explanation via traditional gender ideologies is discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Attitudes toward lesbians and gay men have attracted the attention of researchers for several decades (Herek &McLemore, 2013) due to the great impact they can have on people’s psychological state and behavior. A negative perception of lesbians and gay men was found to be connected with both the approval of discriminatory strategies targeting this group and with violence toward them, as well as with decreased support for their rights (e.g., Gulevich et al., 2018; Patacchini et al., 2014; White &Yamawaki, 2009).

For many years, researchers have studied the factors that might affect attitudes toward gay people (which in this paper includes both lesbian women and gay men unless specified). In particular, they have paid a great attention to gender and sexual differences on the topic. Meta-analytic (Kite &Whitley Jr., 1996) and cross-cultural (Donaldson et al., 2017; van den Akker et al., 2013) studies have demonstrated that, compared to women, men expressed more negative attitudes toward sexual minority individuals. In addition, some studies have shown that straight individuals reported more negative attitudes toward gay people than sexual minorities did (Verweij et al., 2008; Worthen, 2018).

Researchers have attributed these differences to the content of traditional gender ideologies prevalent in societies that emphasize deep and persistent differences between men and women. In particular, scholars suggested that masculine gender ideology, which describes what a man should be and do, is different from feminine gender ideology, which describes what a woman should be and do. Gender differences in attitudes toward gay people are interpreted as the result of endorsements of such ideologies (e.g., Herek &McLemore, 2013). However, this interpretation does not account for diverse people ascribing different meanings to their gender.

Research has revealed that the more a person identifies with a gender in-group, the more they tend to endorse widespread gender beliefs (e.g., Bosson &Michniewicz, 2013; Cadinu &Galdi, 2012). Due to this, gender identity might be associated with attitudes toward gay people. To test this assumption, we conducted a study aimed at examining the relationship between gender identification and attitudes toward lesbians and gay men among people of different genders and sexual orientations.

Gender Ideology and Attitudes toward Gay People

Gender ideology, in broad terms, is usually understood as an individual’s internalization of cultural belief systems and attitudes toward members of a particular gender group. Scholars have focused on traditional gender ideologies that reflect the dominant view of gender roles in Western society prior to the feminist deconstruction of gender. They believe that although such ideologies are widespread in modern societies, members of different groups differ in the degree to which they are endorsed (e.g., Levant &Richmond, 2007).

Traditional masculinity ideology (TMI) is an individual’s internalization of cultural belief systems and attitudes toward men’s roles. It includes norms such as self-reliance, dominance, toughness, restrictive emotionality, and importance of sex (Levant et al., 2015, 2020). Similarly, traditional femininity ideology (TFI) is an individual’s internalization of cultural belief systems and attitudes toward women’s roles. It includes norms such as dependency, caretaking, emotionality, and purity (Levant et al., 2007).

In general, both traditional gender ideologies highlight significant differences between men and women. Nevertheless, society places stricter demands to follow traditional gender roles on men than on women (Herek &McLemore, 2013). These requirements are embodied in two norms that are part of TMI but not of TFI – avoidance of characteristics associated with another gender (i.e., avoidance of femininity), and negative attitudes toward people who “blur the boundaries” between men and women (i.e., sexual minorities).

This assumption is indirectly supported by the evidence from numerous studies conducted on samples of heterosexual men. Previous results revealed that endorsement of TMI was associated with negative attitudes toward women (Corprew III et al., 2014; Gage &Lease, 2018; Hyatt et al., 2017; Lease et al., 2020; Stander et al., 2018) and gay people (Barron et al., 2008; Keiller, 2010; McDermott et al., 2014; Parrott et al., 2002).

Some scholars have suggested that traditional gender ideologies might explain gender differences in attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women. They believe that both men and women tend to endorse common gender beliefs in a society. Since beliefs about men, compared to those about women, imply more negative attitudes toward sexual minorities, men evaluate them more negatively than women do (e.g., Herek &McLemore, 2013).

Nevertheless, we believe that similar reasoning might be used to explain not only gender, but also sexuality differences in attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Scholars have indicated that traditional gender ideologies are more likely to be endorsed by straight people than by sexual minority individuals. In particular, North American scholars who focused on TMI noted that these views best reflect the perceptions of White straight men (e.g., McDermott et al., 2021).

This assumption is also supported by studies that have indicated that straight and sexual minority individuals have different ideas about men and women. In particular, compared to sexual minority individuals, straight people endorse TMI more (Krivoshchekov et al., 2021; Wade &Donis, 2007). This difference is likely due to straight people expressing more negative attitudes than sexual minority individuals toward sexual minorities.

Taken together, studies on traditional gender ideologies may explain the differences in attitudes toward gay people that exist between men and women, and between straight and sexual minority individuals. Nevertheless, they do not account for members of the same gender or sexuality group ascribing different meanings to their gender. To fill this gap, we turn to the examination of gender identity.

Gender Identity and Attitudes toward Gay People

Gender identity is usually referred to as the categorization of oneself as female or male, along with the importance of this categorization for one’s self-definition (Wood &Eagly, 2015). Although gender was demonstrated to be a salient category that drives social interactions (Ellemers, 2018; Rutland, 1999), people may differ in the degree to which they identify with a particular gender group.

According to the model proposed by Leach et al. (2008), gender identification consists of two components. Self-investment (SI) is an emotional-evaluative component that includes a sense of connection with the members of the in-group, positive emotions toward the group, and the belief that belonging to this group is an important part of the self-concept. Self-definition (SD) is a cognitive component that reflects the belief of an individual that they are like other members of the group and all members of the group are alike.

Previous studies revealed that gender identification was associated with the acceptance of stereotypes about men and women: people with stronger gender identification were more likely to ascribe stereotypical features to themselves. For example, the more strongly women identified with their gender, the more they ascribed gender-stereotypic attributes to themselves (Cadinu &Galdi, 2012). However, these trait self-ascriptions were limited to attributes relevant to the gender group stereotype and did not occur with group-irrelevant attributes (Latrofa et al., 2010).

These results suggest that the more strongly people identify with a gender in-group, the more they ascribe the traits that are part of TMI or TFI to themselves. The more the ideology emphasizes the need to maintain existing gender differences, the more it is associated with negative attitudes toward gay people. Since people of diverse genders and sexualities support different gender ideologies, one might assume that in these groups there will be a different relationship between gender identification and attitudes toward gay people.

In particular, since TMI implies stricter adherence to differences between men and women than TFI, we hypothesized that stronger gender identification among men would be associated with more negative attitudes toward lesbians and gay men than among women (hypothesis 1). In addition, since straight individuals were found to endorse traditional gender ideologies more than sexual minority individuals, we hypothesized that stronger gender identification would be associated with more negative attitudes toward lesbians and gay men among straight people than among sexual minority individuals (hypothesis 2).

People with stronger gender identification attribute more stereotypical characteristics to gender in-group members, give a more positive assessment of people who conform to gender stereotypes, and a more negative assessment of people who violate them. In particular, the more strongly men identified with their gender in-group, the more they assigned both positive and negative masculine traits to its members (Bosson &Michniewicz, 2013). They also assessed career men and masculine men more positively, and feminine men more negatively (Glick et al., 2015).

These results allow one to suggest that the more strongly people identify with their gender in-group, the more they would like men and women around them to behave in accordance with traditional gender ideologies. Since, according to traditional gender ideologies, men should emphasize their differences from women more than women do from men, we hypothesized that stronger gender identification would be associated with more negative attitudes toward gay men than toward lesbians (hypothesis 3).

Social Context of the Study

Most of the studies on the relationship between traditional gender ideologies, gender identity and attitudes toward gay people have been conducted in the USA and some European countries that are usually characterized by relatively high levels of gender equality and positive attitudes toward gay people. The current research was conducted in Russia, which is characterized by other features.

First, according to the World Economic Forum’s latest Global Gender Gap Index report, Russia is placed 81st in the Index. Although the gaps for Educational Attainment and Health and Survival have almost closed, Economic Participation and Opportunity and Political Empowerment remain unequal for men and women. Therefore, despite educational and some labor market opportunities, women are still excluded from positions of power in the business and politics sectors (World Economic Forum, 2021).

Cross-cultural studies revealed that countries with low levels of gender equality are characterized by a higher prevalence of traditional gender ideas about men (e.g., Glick et al., 2004) and women (Glick &Fiske, 2001). Recent mass polls conducted on a representative Russian sample demonstrated that respondents tended to value intelligence, the ability to earn money, and striving for success in men, and domesticity, caring, and fidelity in women (Levada-Center, 2018). Participants also described men as hardworking, responsible, executive, and logical, whereas women were described as caring, beautiful, and faithful (Levada-Center, 2020).

Second, Russia is one of the countries that treats straight and sexual minority individuals unequally. In particular, Federal Law No 135-FZ, commonly known as the “anti-gay propaganda law”, limits expression regarding sexual orientation issues (ILGA, 2009). According to recent amendments to the Constitution, marriage is currently considered as being a union between a man and a woman (Morales, 2020). The state does not recognize same-sex unions, and both same-sex marriage and adoption by same-sex couples remain illegal (ILGA, 2009).

Studies showed that countries with low levels of sexuality-based equality are characterized by negative attitudes toward gay people (e.g., ILGA, 2019). Recent surveys conducted by international organizations showed that residents of Russia have negative attitudes toward sexual minority individuals. For instance, based on the Pew Research Center’s report, 74% of respondents stated that homosexuality should not be accepted by our society (Pew Research Center, 2020). In our opinion, features of the social context would strengthen the link between gender identification and attitudes toward lesbians and gay men.

These features of the social context indicate that, on the one hand, traditional gender ideologies are widespread in Russia, and, on the other, there are no social norms that limit the expression of negative attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. We argue that in such circumstances, the relationship between gender identification that encourages acceptance of widespread gender beliefs and attitudes toward gay people would be especially pronounced.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The data were collected during the spring of 2019. Respondents filled out a questionnaire created on the 1KA platform, a Slovenian source application with tools for online surveys. The link to this questionnaire was distributed with the help of social networks (VKontakte, Facebook) that specifically targeted groups with sexual minority individuals as well as general population groups.

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants, who were assured that their data would remain anonymous and confidential. Respondents were also told that the eligibility criteria for their inclusion in the analysis were being aged 16 years or older and being straight or bisexual. Participation was completely voluntary, and the respondents did not receive any reward.

The participants were asked about their gender, age, and sexual orientation. The sample used in the study consisted of a total of N = 851 individuals who indicated their current residency in Russia. Nobody indicated their identity as non-binary. Women comprised 80% of the sample, while the remaining 20% identified as men; 61% (395 women, 122 men) self-identified as heterosexual, while 39% self-identified as bisexual (291 women, 43 men). The age of the participants ranged from 16 to 65, with the mean = 21.45 (SD = 6.92).

Bisexual respondents were recruited on the basis of two considerations. First, they might be considered as sexual minority individuals, and second, they might perceive gay people as an outgroup. In particular, several studies have revealed that bisexual people tend to be excluded by both straight and gay individuals; they were stereotyped as less trustworthy, less inclined toward monogamous relationships and not as able to maintain a long-term relationship (Burke &LaFrance, 2016; Zivony &Lobel, 2014). We suggested that bisexual individuals might also make this distinction between themselves and gay people.

Measures

Gender Identification

To measure in-group identification, we used the inventory developed by Leach et al. (2008). The Russian-language version of this questionnaire (Lovakov et al., 2015) included ten statements reflecting in-group self-investment (SI) and four concerning in-group self-definition (SD). Participants were asked to express the extent of their agreement with each statement on a seven-point scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). Internal consistency reliability coefficients appear in Table 1.

Attitudes toward Gay Men and Lesbian Women

To measure attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women, we used questionnaires measuring the perceived abnormality of non-straight sexual orientation through negative emotions toward gay people and support for their rights. All questionnaires had two different versions used for randomly assigned respondents: one version, presented to 438 participants, referred to ‘gay men’, while the second, referring to ‘lesbian women’, was presented to 413 respondents.

To measure the perceived abnormality of being a gay person, we used the Threat to Morality scale from the Russian Attitudes to Homosexuals Inventory (RAHI; Gulevich et al., 2016). The scale consists of three direct statements (e.g., “Male homosexuality is a sexual perversion”) and two reverse statements (e.g., “Male homosexuality is one of the natural forms of human sexuality”). For each item in the scale, respondents were asked to express the extent of their agreement with the statement on a five-point scale, from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). A higher score indicated a more negative attitude toward gay people. Internal consistency reliability coefficients appear in Table 1.

To measure negative emotions toward gay men and lesbian women, four unipolar scales were used (contempt, anger, disgust, anxiety). Respondents were asked to express the extent of their feeling of these emotions toward gay people on a five-point scale from 1 (“no feeling at all”) to 5 (“strong feeling”). The analysis indicated that all emotions formed one scale. A higher score indicated a more negative attitude toward gay people. Internal consistency reliability coefficients appear in Table 1.

Support for gay rights was measured using six statements. These were borrowed from the previous study (Gulevich et al., 2018) and described the rights to create a family (same-sex marriage, adoption, surrogate parenthood) and to communicate each other (specialized clubs, websites, and mass media targeting gay people). Participants rated whether, in their opinion, each activity should be forbidden or permitted to gay men and lesbian women using a five-point Likert scale from 1 (“should definitely be forbidden”) to 5 (“should definitely be allowed”). A higher score indicated a more positive attitude toward gay people. Internal consistency reliability coefficients appear in Table 1.

Analytical Strategy

The analysis was conducted in three steps. First, means and standard deviations were calculated. Values were compared among subsamples based on gender (men vs. women) and sexual orientation (straight vs. bisexual respondents). Second, regression models that included SI and SD as the independent variables, components of attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women as dependent variables, and one’s age, gender, sexual orientation, and type of attitude toward gay people as controlling variables were tested. To compare the nested linear regression models (i.e., with one component vs. two components of gender identification), we used the R2 and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA).

Third, three types of regression model were calculated to test the hypotheses. All models included respondents’ gender, age, sexual orientation, and two components of gender identification, as well as the type of attitudes toward gay people. At first, we tested the interaction between gender identification and the respondents’ gender (hypothesis 1). Next, the interaction between gender identification and the respondents’ sexual orientation (hypothesis 2) was examined, followed by the interaction between gender identification and the type of attitudes toward gay people (hypothesis 3).

The analysis was conducted in the R environment (R Core Team, 2020). The lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) was used for a series of regression analyses. The Maximum Likelihood Robust (MLR) estimation was used to accommodate any non-normality in the data.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

Means, standard deviations, Cronbach-α for scales, and correlations are presented in Table 1. Results indicated that differences (men vs. women) on the SI (t = −2.29, p = .022, Cohen’s d = −.20) and SD (t = 2.36, p = .019, Cohen’s d = .21) reached the statistical significance threshold. Furthermore, men perceived gay men and lesbian women as more abnormal (t = 6.10, p <.001, Cohen’s d = .66), expressed more negative emotions toward them (t = 3.82, p = .0002, Cohen’s d = .43), and showed less support for both their family (t = −5.40, p <.001, Cohen’s d = −.54) and communication (t = −3.20, p = .0016, Cohen’s d = −.34) rights than women did.

Moreover, straight participants reported higher levels of SD (t = 4.43, p <.001, Cohen’s d = .31) than those who were bisexual, but the difference on the SI level did not reach the chosen statistical significance threshold (t = −.36, p = .72, Cohen’s d = −.03). In addition, compared to bisexual participants, those who were straight perceived gay men and lesbian women as more abnormal (t = 12.98, p <.001, Cohen’s d = .78), expressed more negative emotions toward them (t = 6.02, p <.001, Cohen’s d = .36), and showed less support for both their family (t = −12.28, p <.001, Cohen’s d = −.71) and communication (t = −7.73, p <.001, Cohen’s d = −.48) rights.

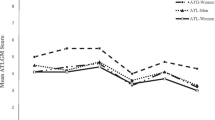

As illustrated in Table 2, attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women were related to respondents’ gender, age, sexual orientation, and types of attitudes toward gay people. After controlling for these variables, higher levels of SD were related to a higher perceived abnormality of both gay men and lesbian women, more negative emotions toward them, and less support for their family and communication rights. At the same time, SI was not related to attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Moreover, the comparison of the nested models demonstrated that adding SI as an additional predictor did not improve the model fit in explaining the perceived abnormality of gay men and lesbian women (F = .083, df = 1, p = .77), negative emotions toward them (F = 1.202, df = 1, p = .27), and support for their family (F = 1.133, df = 1, p = .29) and communication rights (F = 2.690, df = 1, p = .10).

Main Analysis

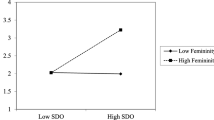

To test hypothesis 1, we ran the linear regression models that included interactions between one’s gender and SI or SD. As illustrated in Table 3, there were differences in the relationship between gender identification and attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women in the subsamples of men and women. Simple slopes analysis (see Table 4) further indicated that, except for the link between SI and support for communication rights, the higher levels of SI and SD components of gender identification were more strongly related to more negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women in the subsample of men than women.

To test hypothesis 2, the models that included interactions between one’s sexual orientation and SI or SD were used. As illustrated in Table 5, there were differences in the relationship between gender identification and attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women in the subsamples of straight and bisexual respondents. Simple slopes analysis (see Table 6) further indicated that higher levels of gender identification were more strongly related to more negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women in the subsample of straight participants. At the same time, results demonstrated that the link did not reach the statistical significance threshold in the subsample of bisexual respondents. The only exception was the significant positive link between SI and support for communication rights in the subsample of bisexual respondents, whereas the link between SI and support for communication rights did not reach the statistical significance threshold in the subsample of straight respondents.

To test hypothesis 3, the models that included interactions between SI or SD and type of attitudes were used. As illustrated in Table 7, with one exception (SD and negative emotions), there was no interaction between the components of gender identification and the gender of gay people (lesbians vs gay men) that reached the chosen statistical significance threshold. In other words, one’s gender identification was related to attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women in a similar way.

For exploratory purposes, we also tested a three-way interaction between respondents’ gender, the gender of gay people (lesbians vs gay men), and components of gender identification (i.e., Gender X Condition X SI or SD). Results indicated that the three-way interaction did not reach the chosen statistical significance threshold in any of the models. In other words, for men and women, strong gender identification was associated with neither more- nor less-negative attitudes toward gay people of their gender.

Discussion

Psychological studies conducted over several decades have demonstrated gender and sexual differences in attitudes toward gay people. They have revealed that, compared to women, men hold more negative attitudes toward gay people, and straight individuals hold more negative attitudes than sexual minority individuals do. Nevertheless, we hypothesized that gender and sexuality interact with gender identification. Therefore, in the current study, we examined gender and sexuality differences and similarities in the relationship between gender identification and attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women.

Overall, the results of our study confirmed the findings of other studies. They indicated that, compared to women, men hold more negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women, and straight individuals hold more negative attitudes than bisexual individuals do. Previous findings also revealed a significant difference: a meta-analysis by Kite and Whitley Jr. (1996) demonstrated that gender differences appear in the assessment of gay people, but not in support of their rights. However, the current results revealed gender differences in assessing the perceived normality of homosexuality, negative emotions toward gay people, and support for their family and communication rights.

In general, the study’s findings supported the assumption that more negative attitudes toward gay people were predicted by stronger gender identification of the respondents. However, the cognitive component of gender identification, which reflects a person’s perception of their similarity with other members of the gender group, was found to be more important than the emotional-evaluative component. Overall, these results are in line with one North American study, in which a strong cognitive component of identification (one’s perception of gender typicality) was associated with more negative attitudes toward gay people (Herek, 1988).

A possible interpretation of this result might be that for the Russian respondents, typical women and men are those with a heterosexual orientation. The more a person believes they are a typical representative of a gender group, the greater the distinction they draw between themselves and gay people, and, as a result, gay men and lesbian women are perceived as strangers. Therefore, the perception of otherness might provoke a more negative attitude toward sexual minority individuals.

The most important results were the interactions between gender and sexuality, on the one hand, and gender identification on the other. First, we assumed that stronger gender identification would be associated with more negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women among men than women. The results fully confirmed this hypothesis. They showed that in the subsample of men, stronger cognitive and emotional-evaluative components of gender identification were associated with more negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women, while in the subsample of women this association was present only for support for communication rights.

In general, these results are in line with those from a Swiss study that demonstrated that strong gender identification was associated with more negative attitudes toward gay people among men, but not women (Falomir-Pichastor &Mugny, 2009). However, the Swiss study involved only straight respondents who answered questions related to the emotional-evaluative component of gender identification. In our study, this pattern maintained itself in a sexually mixed sample and affected both components.

Second, we assumed that, compared to bisexual respondents, gender identification among straight individuals would be associated with more negative attitudes toward gay people. Our results partially supported this hypothesis. Stronger gender identification was related to more negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women in the subsample of straight participants but not bisexual ones (except for the presence of the link between SI and support for communication rights). Taken together, these findings indicated that the link between gender identification and attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women was moderated by gender and sexual orientation.

Third, we hypothesized that gender identification would be associated with more negative attitudes toward gay men than lesbian women. Our results did not support this hypothesis. They revealed that the cognitive and emotional-evaluative components of gender identification were similarly associated with attitudes toward both gay men and lesbian women. This might be due to the cultural context, in which the distinction between gay men and lesbian women is barely made, and gay people are usually referred to as a homogeneous group.

Thus, our study contributes to the existing literature on attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women. First, in previous studies on attitudes toward gay people, researchers focused on the differences between men and women and, less often, on the differences between people with diverse sexual orientations, regardless of the importance they attached to their gender. At the same time, our research has revealed that gender identification, especially its cognitive component, is strongly related to attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women, though the link was moderated by one’s gender and sexual orientation.

Second, previous studies were conducted in North American and European countries, and their results were based on predominantly straight respondents. Our research was conducted in Russia, which is characterized by an emphasis on traditional gender ideologies and discrimination against sexual minorities. Third, bisexual respondents participated in the current study, while a review of previous studies demonstrated underrepresentation and invisibility of their experiences in social sciences (Monro et al., 2017). We believe that inclusion of bisexual experiences may enable the robustness of findings to be tested and provide researchers with new insights.

The findings have practical implications for bias interventions. In the current study, respondents who perceived themselves as similar to other members of a gender in-group and believed that all men (or women) are alike (i.e., the cognitive component of gender identification) reported more negative attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women. One might interpret this as meaning that bias interventions should be aimed at increasing the use of complex ways of thinking about outgroup members to reduce negative attitudes, along with discriminatory behaviors (for more on the topic see Prati et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, the study had several limitations. First, although the sample was large, it was still a convenience sample, and it was possible that participants might have self-selected. We also recruited respondents mostly from social media groups that might have been relatively positive toward gay people. Therefore, no conclusion on a generalized applicability of the findings should be made.

Second, although people with different genders and sexual orientations took part in the study, there were far more women than men and more heterosexual participants than bisexual ones. It is important to keep in mind that the study was aimed at testing the correlational relationship and should not be interpreted in causal terms. In addition, the small number of men did not permit the testing of more complex assumptions about the interactions between gender, sexual orientation, and gender identification. Therefore, in further research, a larger, more balanced sample is needed.

Third, we did not account for the possible socially desirable responses. In Russia, attitudes toward gay people is a sensitive topic, therefore, people might have given socially desirable responses. At the same time, participation in the study was voluntary, the survey was conducted online, and the respondents were guaranteed anonymity. Thus, although possible, we believe it is unlikely that the relationship between gender identification and attitudes toward homosexual individuals would have been affected by social desirability (see Tracey, 2016).

Fourth, our data did not allow for an examination of the link among cisgender and transgender individuals. Emerging evidence (e.g., McDermott et al., 2021) suggests that non-binary and transgender individuals might have a distinct understanding of gender ideologies. Should this be the case, our interpretation of findings would be limited to cisgender men and women. Therefore, future studies should test our interpretation among non-binary and transgender people.

Fifth, while we used the scale that reflects repellent homoprejudice to measure attitudes toward gay people, other ambivalent forms (i.e., adversarial, romanticized, and paternalistic) of prejudice toward gay men were also theorized (Brooks et al., 2020). These forms include other emotions toward gay men and other forms of behavior. Thus, further research needs to address the relationship of gender identification with emotions and behaviors toward gay people that correspond to other forms of homoprejudice.

Data Availability

The dataset analysed during the current study is available in the osf repository, https://osf.io/usvc3/

References

Barron, J. M., Struckman-Johnson, C., Quevillon, R., &Banka, S. R. (2008). Heterosexual men' s attitudes toward gay men: A hierarchical model including masculinity, openness, and theoretical explanations. Psychology of Men &Masculinity, 9(3), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1037/1524-9220.9.3.154.

Bosson, J. K., &Michniewicz, K. S. (2013). Gender dichotomization at the level of Ingroup identity: What it is, and why men use it more than women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033126.

Brooks, A. S., Luyt, R., Zawisza, M., &McDermott, D. T. (2020). Ambivalent Homoprejudice towards gay men: Theory development and validation. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(9), 1261–1289. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1585729.

Burke, S. E., &LaFrance, M. (2016). Lay conceptions of sexual minority groups. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(3), 635–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0655-5.

Cadinu, M., &Galdi, S. (2012). Gender differences in implicit gender self-categorization Lead to stronger gender self-stereotyping by women than by men. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 546–551. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1881.

Corprew III, C. S., Matthews, J. S., &Mitchell, A. D. (2014). Men at the crossroads: A profile analysis of hypermasculinity in emerging adulthood. The Journal of Men' s Studies, 22(2), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.3149/jms.2202.105.

Donaldson, C. D., Handren, L. M., &Lac, A. (2017). Applying multilevel modeling to understand individual and cross-cultural variations in attitudes toward homosexual people across 28 European countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48, 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022116672488.

Ellemers, N. (2018). Gender Stereotypes. Annual Review of Psychology, 69(1), 275–298. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011719.

Falomir-Pichastor, J. M., &Mugny, G. (2009). “I' m not gay. . . . I' m a real man!”: Heterosexual Men' s Gender Self-esteem and Sexual Prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 1233–1243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209338072.

Gage, A. N., &Lease, S. H. (2018). An exploration of the link between masculinity and endorsement of IPV myths in American men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518818430.

Glick, P., &Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56(2), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.109.

Glick, P., Lameiras, M., Fiske, S. T., Eckes, T., Masser, B., Volpato, C., Manganelli, A. M., Pek, J. C. X., Huang, L.-L., Sakalli-Uğurlu, N., Castro, Y. R., D' Avila Pereira, M. L., Willemsen, T. M., Brunner, A., Six-Materna, I., &Wells, R. (2004). Bad but bold: Ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(5), 713–728. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.713.

Glick, P., Wilkerson, M., &Cuffe, M. (2015). Masculine identity, ambivalent sexism, and attitudes toward gender subtypes: Favoring masculine men and feminine women. Social Psychology, 46, 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000228.

Gulevich, O., Osin, E., Isaenko, N., &Brainis, L. (2016). Attitudes to homosexuals in Russia: Content, structure, and predictors. Psychology. Journal of the Higher School of Economics, 13(1), 79–110. https://doi.org/10.17323/1813-8918-2016-1-79-110.

Gulevich, O., Osin, E., Isaenko, N., &Brainis, L. (2018). Scrutinizing homophobia: A model of perception of homosexuals in Russia. Journal of Homosexuality, 65, 1838–1866. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2017.1391017.

Herek, G. M. (1988). Heterosexuals'attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: Correlates and gender differences. Journal of Sex Research, 25(4), 451–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224498809551476.

Herek, G. M., &McLemore, K. A. (2013). Sexual Prejudice. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143826.

Hyatt, C. S., Berke, D. S., Miller, J. D., &Zeichner, A. (2017). Do beliefs about gender roles moderate the relationship between exposure to misogynistic song lyrics and men' s female-directed aggression? Aggressive Behavior, 43, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21668.

ILGA. (2009, May). State-Sponsored Homophobia 2009. https://ilga.org/downloads/ILGA_State_Sponsored_Homophobia_2009.pdf

ILGA. (2019, March). State-Sponsored Homophobia 2019. https://ilga.org/downloads/ILGA_State_Sponsored_Homophobia_2019.pdf

Keiller, S. W. (2010). Masculine norms as correlates of heterosexual men’s attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women. Psychology of Men &Masculinity, 11(1), 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017540.

Kite, M. E., &Whitley Jr., B. E. (1996). Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexual persons, behaviors, and civil rights: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 336–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296224002.

Krivoshchekov, V., Gulevich, O., &Sorokina, A. (2021). Russian version of the male role norms inventory-short form: Structure, validity, and measurement invariance. Psychology of Men &Masculinities. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000346.

Latrofa, M., Vaes, J., Cadinu, M., &Carnaghi, A. (2010). The cognitive representation of self-stereotyping. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(7), 911–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210373907.

Leach, C. W., Van Zomeren, M., Sven, Z., Vliek, M. L., Pennekamp, S. F., Doosje, B., Ouwerkerk, J. W., &Spears, R. (2008). Group-level self-definition and self-investment: A hierarchical (multicomponent) model of in-group identification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 144–165. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.144.

Lease, S. H., Shuman, W. A., &Gage, A. N. (2020). Female and male coworkers: Masculinity, sexism, and interpersonal competence at work. Psychology of Men &Masculinities, 21, 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000218.

Levada-Center. (2018, March 29). Gender Stereotypes. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://www.levada.ru/2018/03/29/gendernye-stereotipy/

Levada-Center. (2020, February 20). Gender Images. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://www.levada.ru/2020/02/20/gendernye-obrazy/

Levant, R. F., &Richmond, K. (2007). A review of research on masculinity ideologies using the male role norms inventory. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 15, 130–146. https://doi.org/10.3149/jms.1502.130.

Levant, R., Richmond, K., Cook, S., House, A. T., &Aupont, M. (2007). The femininity ideology scale: Factor structure, reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, and social contextual variation. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 57(5–6), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9258-5.

Levant, R. F., Hall, R. J., Weigold, I. K., &McCurdy, E. R. (2015). Construct distinctiveness and variance composition of multi-dimensional instruments: Three short-form masculinity measures. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(3), 488–502. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000092.

Levant, R. F., McDermott, R., Parent, M. C., Alshabani, N., Mahalik, J. R., &Hammer, J. H. (2020). Development and evaluation of a new short form of the conformity to masculine norms inventory (CMNI-30). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(5), 622–636. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000414.

Lovakov, A., Agadullina, E., &Osin, E. (2015). A hierarchical (multicomponent) model of in-group identification: Examining in Russian samples. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 18, E32. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2015.37.

McDermott, R. C., Schwartz, J. P., Lindley, L. D., &Proietti, J. S. (2014). Exploring men’s homophobia: Associations with religious fundamentalism and gender role conflict domains. Psychology of Men &Masculinity, 15(2), 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032788.

McDermott, R. C., Wolfe, G., Levant, R. F., Alshabani, N., &Richmond, K. (2021). Measurement invariance of three gender ideology scales across cis, trans, and nonbinary gender identities. Psychology of Men &Masculinities, 22(2), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000286.

Monro, S., Hines, S., &Osborne, A. (2017). Is bisexuality invisible? A review of sexualities scholarship 1970–2015. The Sociological Review, 65(4), 663–681. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026117695488.

Morales, A. (2020, July 2). HRC Denounces Anti-LGBTQ Russian Constitutional Amendment. HRC. Retrieved June 23, 2021, from https://www.hrc.org/news/hrc-denounces-russian-constitutional-amendment-defining-marriage-as-a-union

Parrott, D. J., Adams, H. E., &Zeichner, A. (2002). Homophobia: Personality and attitudinal correlates. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(7), 1269–1278. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00117-9.

Patacchini, E., Ragusa, G., &Zenou, Y. (2014). Unexplored dimensions of discrimination in Europe: Homosexuality and physical appearance. Journal of Population Economics, 28, 1045–1073. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-014-0533-9.

Pew Research Center. (2020). The Global Divide on Homosexuality Persists. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/06/25/global-divide-on-homosexuality-persists/

Prati, F., Crisp, R. J., &Rubini, M. (2020). 40 years of multiple social categorization: A tool for social inclusivity. European Review of Social Psychology, 32, 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2020.1830612.

R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing https://www.R-project.org/.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02.

Rutland, A. (1999). The development of National Prejudice, in-group Favouritism and self-stereotypes in British children. British Journal of Social Psychology, 38(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466699164031.

Stander, V. A., Thomsen, C. J., Merrill, L. L., &Milner, J. S. (2018). Longitudinal prediction of sexual harassment and sexual assault by male enlisted navy personnel. Military Psychology, 30(3), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1037/mil0000171.

Tracey, T. J. G. (2016). A note on socially desirable responding. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(2), 224–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000135.

van den Akker, H., van der Ploeg, R., &Scheepers, P. (2013). Disapproval of homosexuality: Comparative research on individual and National Determinants of disapproval of homosexuality in 20 European countries. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 25(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edr058.

Verweij, K. J. H., Shekar, S. N., Zietsch, B. P., Eaves, L. J., Bailey, M., Boomsma, D. L., &Martin, N. G. (2008). Genetic and environmental influences on individual differences in attitudes toward homosexuality: An Australian twin study. Behavior Genetics, 38, 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-008-9200-9.

Wade, J. C., &Donis, E. (2007). Masculinity ideology, male identity, and romantic relationship quality among heterosexual and gay men. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 57(9–10), 775–786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9303-4.

White, S., &Yamawaki, N. (2009). The moderating influence of homophobia and gender-role Traditionality on perceptions of male rape victims. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(5), 1116–1136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00474.x.

Wood, W., &Eagly, A. H. (2015). Two traditions of research on gender identity. Sex Roles, 73, 461–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0480-2.

World Economic Forum. (2021). The Global Gender Gap Report 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021, from http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2021.pdf

Worthen, M. G. F. (2018). “Gay equals White”? Racial, ethnic, and sexual identities and attitudes toward LGBT individuals among college students at a Bible Belt university. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(8), 995–1011. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1378309.

Zivony, A., &Lobel, T. (2014). The invisible stereotypes of bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 1165–1176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0263-9.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Universität Bern. Data collection has been implemented by the authors on their own initiative without any funding sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gulevich, O., Krivoshchekov, V. & Sorokina, A. Gender identification and attitudes toward gay people: Gender and sexuality differences and similarities. Curr Psychol 42, 7197–7210 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02050-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02050-6