Abstract

The admission of an adolescent to a child and adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit has a serious impact on the entire family unit. The emotional experience of those primary caregivers has been scarcely studied qualitatively despite being recommended by previous research. This study aims to examine the experience of parents of adolescents with mental health needs that required psychiatric hospitalization in a child and adolescent unit. Qualitative cross-sectional research was carried out under the recommendations of Grounded Theory with three Focus Groups of parents (N = 22) of adolescents who required psychiatric hospitalization in a child and adolescent ward. The COREQ quality criteria were applied. The parental experience implies a high level of emotional suffering modulated by feelings of guilt, stigma, parental awareness of their child’s illness and the passage of time. The use of Prochaska’s and Diclemente’s trans-theoretical model of health behavior change is useful in understanding the parental experience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The high prevalence of mental disorders in childhood and adolescence is one of the major challenges of the twenty-first century (WHO, 2005). Polanczyk et al. (2015) puts the aggregate prevalence at 13.4%.

Over the past several years, researchers have become increasingly interested in the family’s experience in caring for people with mental disorders. Weller et al. (2015) reviewed previous research on the impact of psychiatric hospitalization on informal caregivers. Rodríguez-Meirinhos et al. (2018) offer in their review an overview of the support needs perceived by family caregivers. Both reviews consider that future research should take into account characteristics such as the severity of the mental disorders they suffer and/or the age at which they appear.

The two reviews mentioned above collect information provided by research with children, adolescents and young people between the first and third decade of life. Bearing in mind that according to the WHO adolescence extends from 10 to 19 years of age (WHO, 2014) and normative age for the onset of puberty is 8 to 13 years in girls and 9 to 14 years in boys (Giedd, 2018) we cannot claim that the results are specific for the stage of adolescence. As an example, Oruche et al. (2012) captures the experience of primary caregivers of children aged 2–17 with mental health needs. In studies involving ages above 18 years (Jivanjee et al., 2009; Lindgren et al., 2016; Sin et al., 2005), we find the experience of transitioning to adult psychiatric services reported as difficult to discern at what point they felt one way or another.

Other studies on the subject have focused attention on the specific needs of adolescents with disruptive behavior disorder (Oruche et al., 2014)], autism spectrum disorder (Nichols & Blakeley-Smith, 2010), psychosis (Shpigner et al., 2013; Sin et al., 2005), or deliberate self-harm (Byrne et al., 2008), or have been focused on service evaluation for accessibility and appropriateness (Coyne et al., 2015), or on the relationship with health professionals and role change at the family level (Harden, 2005). Research in which participating parents are recruited after or during their child’s hospitalization in a child and adolescent psychiatric unit is less common, and we also find the experience focused on certain adolescent diagnoses such as depression (Snell et al., 2010), or suicide attempts (Wagner et al., 2000).

However, most child and adolescent psychiatric hospitalization units are not specific to a single need or diagnosis, but respond to the severity of the adolescent’s situation. In order to understand the experience of the parents of adolescents admitted to these units, all adolescents and parents should be included, focusing on people as global beings and on their lived experience and the interpretation, they make of it, and not on sociodemographic characteristics, or diagnosis. Focusing on one type of approach/treatment/disruption, which is not part of the reality of the units, could cause loss of input or different nuances, thus diminishing the breadth of the experience with the inpatient unit.

Therefore, the aim of this research was to examine and gather information on the experience of parents of adolescents with mental health needs who were admitted to a child and adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit, in order to provide useful meanings in the understanding of aspects related to their subjective experience.

Methods

This research is framed within the constructivist paradigm. Methodologically, it is based on Grounded theory. Qualitative research with focus groups were considered optimal for this study (Kitzinger, 1995; Krueger & Casey, 2000; Morgan, 1998). The COREQ quality criteria were applied (Tong et al., 2007). The research team made up of three MD-PhD psychiatrists (one man and two women), one RN-PhD mental health nurse (woman) and three mental health nurses (one man and two women), has experience in qualitative research through focus groups (González-Torres et al., 2007; Gonzalez-Torres & Fernandez-Rivas, 2019; Pardo et al., 2020).

Selection of the Sample and Focus Group

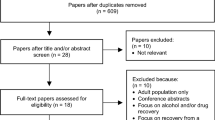

The scope of the research was the parents of adolescents who had been admitted at least once to the child and adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit of the Basurto University Hospital during 2017. The medical records were reviewed and the criteria for inclusion and exclusion were applied. It is detailed in Table 1.

The selection of the sample was carried out by means of convenience sampling. A total of 59 parents were invited by telephone to collaborate in the study (32 women and 27 men) of which 22 finally participated (mean age 50.5 SD: 6.03). Sociodemographic and clinical data are shown in Table 2.

The reasons for their refusal to participate or their absence were: 13 did not wish to participate, 10 incompatibility with work schedules, 5 lack of time, 5 they did not provide any reason, 3 they had to take care of their children, and 1 another appointment arose for the same day. The study meets both international and local ethical research criteria.

Data Collection and Data Analysis

Preliminary questioning path was developed with the questions that met the recommendations for a focus group (Krueger & Casey, 2000). This script was pilot tested in an in-depth interview with two parents who met the inclusion criteria.

Three focal groups of approximately 90 min duration were held until the theoretical saturation of the central categories of analysis was reached. There were 20 participants, 8 in the first group, 6 in the second and 6 in the third. The focus groups 1–2 were moderated by a senior psychiatrist and observed by a mental health nurse and in group 3 they exchanged their roles in order to favour triangulation in obtaining the data. Both researchers had no prior or subsequent contact with the adolescents or their parents. To facilitate the anonymity of the participants, they were assigned a personal code (example: G3P18W) consisting of G (focus group number), P (participant number) and W or M (woman/men).

The information was recorded on audio and video, transcribed, and incorporated into MAXQDA version 12 (VERBI Software GmbH, 2015). Data analysis was conducted by 2 senior psychiatrist and 2 mental health nurses. The recommendations provided by Grounded Theory were followed (Corbin & Strauss, 2008; Glaser & Strauss, 1967), the process is shown in Table 3. Finally, all participants were again summoned to show them the results obtained, 8 participants attended, showed their agreement with the results presented.

Results

The organization of the experience made by the participants in their speeches has been respected. The first three categories (Experience before admission, Experience during stay, and, Experience after discharge) have a temporal relationship between them, as stages of a process. The other three emerging categories (Proposals for Improvement, Guilt and Stigma), performing a modulating function. We used both “in vivo” codes (collecting expressions from the participants themselves) and technical codes promoted by the researchers’ previous knowledge of the field of study (such as the terminology used by Prochaska and DiClemente in the Trans-theoretical Model of health behavior change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984).

Experience before admission.

All parents detected changes in their adolescent children’s behavior before admission.

Contemplative state of illness

Parents with illness insight about their children view their changes as a problem/difficulty in which they must intervene.

“... we saw that there was something very rare, that there was something very rare that... very rare that we didn’t know what it was that was escaping us but needed attention now...” G3P18W.

Previous difficulties.

Parents without problem/illness insight believed that the changes were part of adolescence, resorted to professionals who did not guide them correctly or their children hid part of the symptoms from them.

“Yes, we were seeing something but well sometimes you say well I think this, like you’re trying to cover it up, you don’t think it can be like that.” G3P18W.

Motivation for admission.

The passage of time and the exacerbation of the symptoms, with the appearance in some cases of life risk, or the request by the adolescent himself, motivates the parental decision to resort to hospitalization.

“Every hour that passed my son got worse...” G3P18W.

Emotional suffering.

Parents enter the hospital with a lack of information regarding the care provided in the unit. This increases their level of suffering, generating uncertainty and anxiety in the face of the unknown.

“... the first time they are admitted we don’t know where we left our children, it is a psychiatric unit such and such..., but where will it be? how will it be? “ G1P1M.

Pre-admission expectations.

They consider admission to be the last resort for help. Parents make a decisive balance between the expectations of obtaining help for their children and themselves, and the emotional suffering caused by being aware of their own limitations.

“The situation had to be stopped because it was getting out of hand and was being detrimental to her” G2P12M.

Experience during stay (Main category).

The overall experience was hard and emotionally charged, even though they left their children in what they felt was the right place and this gave them a mixture of calm and reassurance.

“…this was very hard but it was an inner peace. G3P18W.

Day of admission.

The experience of the day of admission was traumatic for the parents. The collaboration of the adolescent improves the experience.

“Well I had the worst day of my life by far.” G1P1M.

The application of restrictive care such as the use of mechanical restraint or the removal of dangerous objects during the admission of adolescents causes a stigmatizing experience for parents.

“Because the feeling of being in jail is there, I had it too ... but ... they explained it to me ... but the feeling of jail is terrible...” G1P8M.

The periods in which parents receive less information about the state of their children (first 24 h after admission with no visits allowed) increase parental suffering.

“But those 24 hours are ... we were crying for hours in bed without moving, thinking about what is happening to him, what problems he has, what they are doing to him...” G1P1M.

Visits.

This is a key time throughout the stay for the parents’ relationship with the adolescents and the parents’ relationship with the unit and the nursing professionals.

“And then there are things about the unit that are very shocking, aren’t there? You feel totally watched, controlled, in a very compromised environment, you don’t know how to move or how to sit...” G2P14W.

The recommendation to parents to work on management strategies during visits is sometimes experienced as a task that should be done by a therapist and not by them.

“... and I did have that feeling... of saying fuck, but do I have to be the therapist? But... what a pressure, right? My God! I can’t, I can’t with this pressure!” G2P11W.

Parents suffer and blame themselves for having to confront their own feelings and their children about the need to stay in hospital and the application of sometimes restrictive care interventions (usually in patients with life-threatening Body Mass Indexes).

“... and they won’t even let me go out to play ping-pong, it’s good because it has to be clear [crying]... it’s hard but it was encouraging to know that I was where I needed to be.” G3P18W.

Functions attributed to nursing by parents.

The functions observed by the parents and assigned to nursing were: reception in the unit, management of visits with continuous presence and, daily information on basic care and evolution of adolescents that creates a link between parents and nursing staff. In general, the evaluation was positive.

“I think from what you’ve said about nursing..., that bond, that “bubble”, that’s... I think that’s what’s fundamental…[...]….in our case that the best help was when we went out and talked to the nurse every day we talked there ... ... the day to day that was very hard because the only way out was the nurse who welcomes you there at the door with ...”. G3P17M.

Functions attributed to Psychiatrists by parents.

The parents considered the role of the psychiatrist are to carry out and communicate the diagnosis of the adolescent, information on the evolution during stay and, before discharge of the adolescent, information on guidelines for action and use of medication. Some parents were dissatisfied with the information provided and felt blamed during the interviews.

“Then I met the psychiatrist..., which were the steps that the illness was going to follow... and all this..., well, was not at all comforting.” G3P17M.

Share information about admission.

Parents did not share news of their child’s admission. They communicated it only to family members who they felt could support, help, and/or accompany them in the process.

“In my case, to the people closest to me..., if you open up..., right? Because you also need their help, but, but... in another context... no.” G1P4M.

In the adolescents schools, teachers were informed. Class mates were generally not informed, or the information provided did not entirely reflect reality as a protection against the feared stigma.

“... why doesn’t he come as usual, why doesn’t he... You have to give them an explanation, sometimes a good one because a white lie is the best there can be or a half-truth...” G3P18W.

Discharge.

At the end of the admission the parents reported fear and uncertainty. They did not feel capable or trained to manage the difficulties at home.

“Now when we go home, what do we do?” G2P12M.

Experience after discharge.

Results of the hospitalization.

The results of the stay the parents mention were: greater insight about illness itself and its severity, behavioural changes in adolescents, and acceptance of hospitalisation as part of a process that continues aferwards.

“If my daughter were not admitted, she would not be alive right now.” G1P3W.

Repercussions on the family.

The impact on the family nucleus is high, both on its health and on the relationship between the parents, which suffers greatly from the differences of opinion between the two, and can become a motivating factor in an eventual separation or divorce.

“…it is very probable that I say: ‘look, I have enough with the child’,... to put up with you, to ..., look, that’s it, we’re done.” G1P1M.

“I was on sick leave for depression...” G1P5W.

There are also an impact on adolescents siblings either because parents are focused on the hospitalized child or because of impact on the social environment due to stigma.

“... and there are some great forgotten ones here, and it’s not the parents or the patients, I think it’s the siblings.” G2P14W.

Repercussions in School.

Support from schools was highly valued. Their children were afraid of being judged negatively by their peers.

“She was very afraid, she had to do it, plus she wanted to do it very quickly, but she was afraid.” G3P16W.

Follow-up.

Valuations were more positive when children remained in the hospital outpatient unit for follow up than when they attended the community mental health centre.

“When she’s here she’s fine, but when she leaves...there’s a bit of a void.”

G1P3W.

Succesive admissions.

In cases of re-entry into the unit, parents feel increased anxiety about the evolution of their children’s difficulties.

“I have become more distressed with each admission, because I saw that I was getting into a spiral of which, as I saw, I was getting more down into the pit...” G2P12M.

The parental experience of the unit is sometimes better than in the first admission because they know the protocols and the staff.

“... well, he keeps on being admitted, but he keeps on being admitted with optimism, he feels very loved...” G1P4M.

Proposals for improvement.

Parents mention several aspects to improve: continuity between levels of care (connection between Hospital and Community Mental Health Centers), uniformity in the indications (given by different professionals), accessibility and availability of professionals, more detailed information provided throughout the process, and placing the work with families at the centre of the process of care.

Feeling of guilt.

Parents felt guilty at many times during their children hospitalization. The reasons mentioned were:

We did not notice.

They feel that they should have been more aware of their children’s difficulties.

“... you feel super guilty, super bad, you think you are to blame for everything you have missed out on along the way...” G3P16W.

Will there be another option?

Some parents speak about delaying the decision to seek admission until you feel like you’ve abandoned your children.

“When he opened his arms to me it was a gift and I told him this is a gift because I felt terrible that I had left him here.” G2P14W.

Guilty for the disease itself.

They feel they must communicate the difficulties detected in the adolescents since their story has importance for the diagnosis, and they consider that there are no objective tests.

“... is the feeling of guilt... all the time because that is what you say... because ...they could treat me instead...” G2P11W.

I felt helpless.

They felt overwhelmed and unable to manage situations with their children.

“... then I felt powerless at that moment, because I didn’t know what to do with my child.” G1P2W.

Stigma.

Parents described situations in which the presence of social stigma towards mental disorders was detected.

Triggers.

The parents considered that the social stigma is triggered and/or increased by police intervention in the family home and also in emergency units because these patients did not have their own space and staff had no specific training in mental health (structural stigma).

“I now have it very clear [after multiple admissions] that to enter the emergency department, that is, there should be a psychiatric section where the staff knows what to do, that is, where orderlies and nurses know what they are talking about and make our lives easier...”. G1P3W.

They felt that society is uninformed and therefore they are not understood and are stigmatized both their children and themselves (courtesy stigma). They felt judged as bad parents and permissive.

“I’ve been told, it’s just... as parents... you give him too much, uh... you’ve been too permissive...” G2P12M.

Family stigma.

The stigma reached the entire family unit.

“So it is a stigma. It’s stigmatized all of us, we’re like asking permission and forgiveness from the whole family for all the chaos, right?” G2P12M.

Coming also from the parents themselves as members of society (self-stigma), when they make categorizations between normals and their children.

“You feel a bit like the father of a freak, don’t you, because obviously it’s not what... statistically it’s not what’s usual...” G1P4M.

Consequences of Stigma.

They detected contempt compared to physical disorders. Adding to their need to protect their children from stigma caused them not to share their experience, thus encouraging widespread misinformation.

“Then it is also hard to think that it is a disease just like another one... I do not know, maybe the word I am going to say is very strong..., but contempt, disdain or such...”G3P18W.

Discussion

The awareness of illness or problem that parents of adolescents have prior to hospitalization marks their emotional experience. To address the heterogeneity of parental experiences and reactions, we consider it useful to make use of the Trans-theoretical Model of Health Behavior Change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984) and understand the entire process as a health change of the family unit made up of the adolescent and his or her parents.

The trans-theoretical model understands changes in health as a cyclical process through five stages (pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance), in which each person needs variable time and motivation, and the implementation of different processes of change (strategies and techniques they use to produce change) to progress from not considering the need for a change in health to the realization and adaptation of that change (Prochaska, 1999; Prochaska & DiClemente, 2005; Prochaska & Velicer, 1997).

In this way we understand that many parents are in a pre-contemplative or contemplative stage, when the need for hospitalization of their adolescent children becomes urgent. This implies a confrontation with their perception of the seriousness of their children’s condition, which generates guilt, impotence, frustration in their performance of the parental role, and fear and uncertainty when they feel pressured to decide to seek admission of their children to a unit whose functioning and even existence they are unaware of. This misinformation is mediated by the social stigma towards mental disorders that conditions the quantity and quality of information available about the unit (Lindgren et al., 2016; Olasoji et al., 2017) and the general experience of the parents.

The increase in insight over time and the observation of the deterioration of their children allows them to move on to the preparation stage where, despite the high emotional suffering and guilt caused by the income, the decisional balance leans positively, moved by fear of the poor evolution of their children and the hope of a functional and symptomatic improvement (Ronzoni & Dogra, 2012). Using the processes of change of “dramatic aid” where they evaluate emotionally how the modification of the current situation could provide them with relief, the “self-evaluation” with which they combine a cognitive and emotional evaluation and imagine a future without a health problem, and/or the “environmental re-evaluation” where they evaluate how the problem affects them in their social environment (Prochaska, 1999), they manage to gather enough motivation to move on to the action stage or period of hospitalization.

The experience of the day of admission, despite being traumatic on all occasions, is better as long as the adolescent is informed and he shows collaboration (Wiens & Daniluk, 2009). Otherwise, undesirable situations may arise such as police intervention or the use of restraints at the adolescent’s home and/or during the transfer to the hospital, which favors the stigmatizing perception and guilt of the parents. The perceived lack of information continued to condition the experience of the parents during the hospitalization process. The implementation of security measures such as the removal of dangerous objects, the application of restrictive interventions (e.g. prohibition of physical exercise to patients with Anorexia Nervosa) or the insufficient information during the first 24 h generates suffering, fear and helplessness and is described as a heartbreaking experience. All of these measures are subsequently understood as beneficial care when they are calmly and thoroughly explained to them, and they have time to rationally integrate them with the seriousness of their children’s condition.

The passage of time, another modulating factor of the parental experience, allows parents to leave behind the emotional storm in which they are immersed at the beginning of the stay, and to give way to a more cognitive assessment and the application of behavioural change processes such as “stimulus control” with the modification of the environment, “counter-conditioning” with the learning of behaviours that replace behavioural problems, or “contingency management” with the reinforcement of healthy behaviours (Prochaska, 1999). These processes are fostered by the very framework of containment offered by hospitalization and parents are advised to deepen these processes from day one during visits to their children. The initial experience is negative, as they do not feel prepared for it and consider that it should be carried out by a professional. In this reaction, the expectation of adolescents and parents to encounter a traditional medical model seems to play a role, in which their role is limited to being providers of information that professionals will have to evaluate in order to make a diagnosis and indicate and administer treatment. In a psychiatric hospitalization unit of this type, both the patient and the families should take a less passive role and be co-participants in the therapeutic effort. This change of role still needs time to develop.

In longer hospitalizations, greater integration is observed (Bjørngaard et al., 2008). Parents often did not feel prepared for the return of the adolescents to the family home, mainly during the shorter hospitalizations, and considered that they had not received sufficient information, guidelines or training in adolescent management skills and medication at home from the psychiatrist (Fawley-King et al., 2013). This fact generated anticipatory distress upon discharge (Nordby et al., 2010) and uncertainty about the evolution of the adolescents. They did not feel supported at the family level (Jivanjee et al., 2009; Olasoji et al., 2017; Young, 2018).

All of the above can be understood by understanding that parents arrive at the hospitalization of their children without being in the action stage of the hospitalization itself. Resistance and difficulties appear in integrating the indications of the professionals and the care applied to their children. Not using strategies adapted to each stage can lead to a lack of motivation and adaptation to the therapeutic plan (Mccann et al., 2012). Therefore, mental health professionals should investigate from the initial contact about the phase of change in which the parents are, and thus be able to adapt to their variable needs and individualize the therapeutic approach. If the efforts of professionals are directed at a phase in which parents are not present, they are not very effective.

The maintenance phase would begin after the end of the hospitalization period. Parents report repercussions on the entire family system: destabilization of the couple and family (Shpigner et al., 2013), different distribution of parents time to the detriment of other children (and this make them feel guilty), or, to the detriment of the parents’ work/social activities. The relapse stage would lead to new hospitalizations in those adolescents who needed it.

Parents hid information about their children’s health for fear of the consequences of the social stigma detected (Shpigner et al., 2013; Stengler-Wenzke et al., 2004). They only share information that is essential for the adolescent’s return to the school and, in case they need it, the help or support of a family member or close friend. The presence of social, structural and courtesy stigma towards the closest family members and self-stigmatization in the parents of adolescents has been noted.

Parents point out to some improvements: increase continuity between levels of care (Plaistow et al., 2014), uniformity in the indications (Teggart & Linden, 2006), accessibility and availability of professionals (Coyne et al., 2015), information provided throughout the process (Lindgren et al., 2016; Oruche et al., 2012), and work with families as the focus of care (Lelliott et al., 2001).

Limitations and Strengths of the Study

The limitations of the study are related to the qualitative methodology itself. The strengths of the study are: recruitment from the level of hospitalization. Balanced composition of the sample at gender. No diagnostic focus to avoid loss of input. Carried out on parents caring for adolescents between 13 and 17 years of age and who are not transferred to the adult hospitalisation unit. To the best of our knowledge, no study of these characteristics has yet been made.

Summary

This study analyzed information on the experience of parents of adolescents with mental health needs who required psychiatric hospitalization in a child and adolescent unit in Spain. The parental experience of an adolescent child’s stay in a child and adolescent psychiatric inpatiente unit is one of great emotional suffering in which anguish, fear, uncertainty, hope, frustration, helplessness, isolation, loneliness, guilt, and contempt appear.

The application of the Prochaska and DiClemente Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change facilitates the understanding of the heterogeneity of parental emotional reactions. Knowing the phase of change in which parents find themselves and adapting therapeutic efforts to their needs should become an important objective for professionals involved in adolescent and family care from the first contact with mental health services.

The parental experience was modulated by the presence of illness insight, guilt, stigma, and, personal need for time to integrate changes. The greater the sense of guilt and perception of stigma (social-structural-courtesy), the greater the suffering and the worse the overall experience. The less parental awareness of the children’s illness and the less time available to integrate the changes produced, the greater the parental suffering and the worse the overall experience.

In order to improve the parental experience, it is necessary to optimise the information provided, the family accompaniment and the continuity of care. Implementing a model of collaborative care and a family focus in which parents are not only a valuable resource for the recovery of adolescents, but also have their own space to share their concerns and receive training, would undoubtedly improve their experience.

Data Availability

Transcriptions are kept by the authors. Interested researchers can access them contacting the corresponding author and after complete anonymisation of participants is secured.

References

Bjørngaard, J. H., Andersson, H. W., Ose, S. O., & Hanssen-Bauer, K. (2008). User satisfaction with child and adolescent mental health services. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(8), 635–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0347-8.

Byrne, S., Morgan, S., Fitzpatrick, C., Boylan, C., Crowley, S., Gahan, H., Howley, J., Staunton, D., & Guerin, S. (2008). Deliberate Self-harm in Children and Adolescents: A Qualitative Study Exploring the Needs of Parents and Carers. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 13(4), 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104508096765.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research (3rd ed.): Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. SAGE publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153.

Coyne, I., McNamara, N., Healy, M., Gower, C., Sarkar, M., & McNicholas, F. (2015). Adolescents’ and parents’ views of child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) in Ireland: Adolescents’ and parents’ views of CAMHS. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22(8), 561–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12215.

Fawley-King, K., Haine-Schlagel, R., Trask, E. V., Zhang, J., & Garland, A. F. (2013). Caregiver participation in community-based mental health Services for Children Receiving Outpatient Care. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 40(2), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-012-9311-1.

Giedd, J. N. (2018). A ripe time for adolescent research. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28(1), 157–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12378.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine.

Gonzalez-Torres, M. A., & Fernandez-Rivas, A. (2019). Return to Sepharad: Is it possible to heal an ancient wound? A reflection on the construction of large-group identity. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 28(2), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/0803706X.2017.1420231.

González-Torres, M., Oraa, R., Arístegui, M., Fernández-Rivas, A., & Guimon, J. (2007). Stigma and discrimination towards people with schizophrenia and their family members: A qualitative study with focus groups. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42(1), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0126-3.

Harden, J. (2005). “Uncharted waters”: The experience of parents of Young people with mental health problems. Qualitative Health Research, 15(2), 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304269677.

Jivanjee, P., Kruzich, J. M., & Gordon, L. J. (2009). The age of uncertainty: Parent perspectives on the transitions of Young people with mental health difficulties to adulthood. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18(4), 435–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-008-9247-5.

Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research: Introducing focus groups. BMJ, 311(7000), 299–302. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299.

Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2000). Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Publisher: (3rd edition) Sage publication - international educational and professional Publisher; London.

Lelliott, P., Beevor, A., Hogman, G., Hyslop, J., Lathlean, J., & Ward, M. (2001). Carers’ and users’ expectations of services – User version (CUES–U): A new instrument to measure the experience of users of mental health services. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 179(1), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.179.1.67.

Lindgren, E., Söderberg, S., & Skär, L. (2016). Being a parent to a Young adult with mental illness in transition to adulthood. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(2), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2015.1092621.

Mccann, T. V., Lubman, D. I., & Clark, E. (2012). The experience of young people with depression: A qualitative study: Young people with depression. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(4), 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01783.x.

Morgan, D. L. (1998). The focus group guidebook. SAGE Publications, Inc., https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483328164.

Nichols, S., & Blakeley-Smith, A. (2010). “I’m not sure We’re ready for this …”: Working with families toward facilitating healthy sexuality for individuals with autism Spectrum disorders. Social Work in Mental Health, 8, 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332980902932383.

Nordby, K., Kjønsberg, K., & Hummelvoll, J. K. (2010). Relatives of persons with recently discovered serious mental illness: In need of support to become resource persons in treatment and recovery. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 17(4), 304–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01531.x.

Olasoji, M., Maude, P., & McCauley, K. (2017). Not sick enough: Experiences of carers of people with mental illness negotiating care for their relatives with mental health services. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 24(6), 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12399.

Oruche, U. M., Downs, S., Holloway, E., Draucker, C., & Aalsma, M. (2014). Barriers and facilitators to treatment participation by adolescents in a community mental health clinic: Barriers and facilitators to treatment. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21(3), 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12076.

Oruche, U. M., Gerkensmeyer, J., Stephan, L., Wheeler, C. A., & Hanna, K. M. (2012). The described experience of primary caregivers of children with mental health needs. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 26(5), 382–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2011.12.006.

Pardo, E. S., Rivas, A. F., Barnier, P. O., Mirabent, M. B., Lizeaga, I. K., Cosgaya, A. D., Alcántara, A. C., González, E. V., Aguirre, B., & Torres, M. A. G. (2020). A qualitative research of adolescents with behavioral problems about their experience in a dialectical behavior therapy skills training group. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 245. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02649-2.

Plaistow, J., Masson, K., Koch, D., Wilson, J., Stark, R. M., Jones, P. B., & Lennox, B. R. (2014). Young people’s views of UK mental health services: Young people’s views. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 8(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12060.

Polanczyk, G. V., Salum, G. A., Sugaya, L. S., Caye, A., & Rohde, L. A. (2015). Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(3), 345–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12381.

Prochaska. (1999). How do people change, and how can we change to help many more people? En M. A. Hubble, B. L. Duncan, & S. D. Miller (Eds.), The Heart and Soul of Change—What Works in Therapy (pp. 227–255). American Psychological Association.

Prochaska, & DiClemente, C. (2005). The Transtheoretical approach. En J. C. Norcross & M. R. Goldfried (Eds.), Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration (second edition, pp. 147–171). Oxford University Press, USA.

Prochaska, & DiClemente, C.C. (1984). The transtheoretical approach: Crossing traditional boundaries of therapy. Dow Jones-Irwin.

Prochaska, & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion: AJHP, 12(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38.

Rodríguez-Meirinhos, A., Antolín-Suárez, L., & Oliva, A. (2018). Support needs of families of adolescents with mental illness: A systematic mixed studies review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 32(1), 152–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2017.09.004.

Ronzoni, P., & Dogra, N. (2012). Children, adolescents and their carers’ expectations of child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS). International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 58(3), 328–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764010397093.

Shpigner, E., Possick, C., & Buchbinder, E. (2013). Parents’ experience of their child’s first psychiatric breakdown: «welcome to hell». Social Work in Health Care, 52(6), 538–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2013.780835.

Sin, J., Moone, N., & Wellman, N. (2005). Developing services for the carers of young adults with early-onset psychosis – Listening to their experiences and needs. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 12(5), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2005.00883.x.

Snell, C., Marcus, N. E., Skitt, K. S., Gonzalez-Heydrich, J., & DeMaso, D. R. (2010). Illness-related concerns in caregivers of psychiatrically hospitalized children with depression. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 27(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865711003738498.

Stengler-Wenzke, K., Trosbach, J., Dietrich, S., & Angermeyer, M. C. (2004). Experience of stigmatization by relatives of patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 18(3), 88–96.

Teggart, T., & Linden, M. (2006). Investigating service users’ and Carers’ views of child and adolescent mental health Services in Northern Ireland. Child Care in Practice, 12(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575270500526253.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

VERBI Software GmbH. (2015). MAXQDA (Versión 12) [Computer software]. https://www.maxqda.com/

Wagner, B. M., Aiken, C., Mullaley, P. M., & Tobin, J. J. (2000). Parents’ reactions to adolescents’ suicide attempts. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(4), 429–436. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200004000-00011.

Weller, B. E., Faulkner, M., Doyle, O., Daniel, S. S., & Goldston, D. B. (2015). Impact of patients’ psychiatric hospitalization on caregivers: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 66(5), 527–535. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400135.

WHO. (2005). Mental health: Facing the challenges, Building Solutions: Report from the WHO European Ministerial Conference of Helsinki. WHO Regional Office for Europe. http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/action_plan/es/

WHO. (2014). Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health, and Ageing. https://www.who.int/teams/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-health-and-ageing/maternal-health/about/mca

Wiens, S. E., & Daniluk, J. C. (2009). Love, loss, and learning: The experiences of fathers who have children diagnosed with schizophrenia. Journal of Counseling & Development, 87(3), 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2009.tb00115.x.

Young, L. (2018). Exploring the experiences of parent caregivers in schizophrenia. School of Nursing Faculty of Health Sciences University of Ottawa.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the Basque Health Innovation and Research Foundation (BIOEF reference OSIBB18/003) and by Basurto University Hospital. The funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BMS: Corresponding autor, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing / original draft.

AFR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing / original draft.

KLOS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing / original draft

FJSA: Investigation (focus group leader), Resources.

ESP: Resources

EVG: Resources

MAGT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation(focus group leader), Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing / original draft.

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate an Publication

The study was carried out in accordance with local regulations and internationally established principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013). Written consent was obtained from all participants. Their participation was voluntary and they received no incentive. Confidentiality (Spanish data protection law 15/99) and the will of those subjects who did not want to participate in the study has been respected at all times. Likewise, study was assessed and approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of Basurto University Hospital.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Merayo-Sereno, B., Fernández-Rivas, A., de Oliveira-Silva, K.L. et al. The experience of parents faced with the admission of their adolescent to a child and adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit. A qualitative study with focus groups. Curr Psychol 42, 6142–6152 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01901-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01901-6