Abstract

Based on assumptions of the Job Demands-Resources model, we investigated employees’ willingness to use prescription drugs such as methylphenidate and modafinil for nonmedical purposes to enhance their cognitive functioning as a response to strain (i.e., perceived stress) that is induced by job demands (e.g., overtime, emotional demands, shift work, leadership responsibility). We also examined the direct and moderating effects of resources (e.g., emotional stability, social and instrumental social support) in this process. We utilized data from a representative survey of employees in Germany (N = 6454) encompassing various job demands and resources, levels of perceived stress, and willingness to use nonmedical drugs for performance enhancement purposes. By using Structural Equation Models, we found that job demands (such as overtime and emotional demands) and a scarcity of resources (such as emotional stability) increased strain, consequently directly and indirectly increasing the willingness to use prescription drugs for cognitive enhancement. Moreover, emotional stability reduced the effect of certain demands on strain. These results delivered new insights into mechanisms behind nonmedical prescription drug use that can be used to prevent such behaviour and potential negative health consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the last decades, processes such as digitalization, flexibilization, and the expansion of the service sector have significantly transformed the work environment (e.g., Brühl & Sahakian, 2016; Fink, 2016; Siegrist, 2016). Consequently, the nature of jobs and work demands has changed. While physical demands seem to decline, cognitive and emotional demands as well as work pressure have increased (Fink, 2016).

High work demands are known for causing stress in individuals (i.e., strain, which is the psychological and physiological response to those stressors (Siegrist, 2002)). This provokes different negative consequences such as job dissatisfaction, mental and physical health problems, absenteeism, or productivity losses (Barnes & Zimmerman, 2013; Siegrist, 2016; Tecco et al., 2013). Thereby, these stressors have negative impacts across indivdiuals, the economy, and society as a whole.

Because many jobs require high levels of concentration, wakefulness, and cognitive functioning, the strain they induce leads to depleted cognitive capacity (cf., Brühl & Sahakian, 2016; Sattler, 2019). If stress-buffering personal resources such as social support or self-efficacy are limited, some individuals might relieve or reduce their strain by using substances such as alcohol (Frone, 2016; Lo et al., 2014; Ruisoto et al., 2017; Unrath et al., 2012) or by engaging in physical activity (Brand et al., 2020; Gerber et al., 2015; Gudmundsson et al., 2015; Lindegård et al., 2015).

A newer way to deal with cognitive requirements and strain are prescription drugs that are usually prescribed to treat diseases such as attention-deficit hyper-activity disorder or narcolepsy. These drugs include substances such as modafinil (e.g., Provigil), methylphenidate (e.g., Ritalin), or Amphetamine-Dextroamphetamine (e.g., Adderall). But indivudals also use them without prescription with the intention to counteract their sleepiness and exhaustion, or to improve their memory and concentration (Greely et al., 2008; Smith & Farah, 2011). However, studies and subsequent meta-analyses show that potential enhancement effects are often limited (Repantis et al., 2010; Smith & Farah, 2011; Weyandt et al., 2018). Moreover, user expectations seem to partially exceed the actual effects.

Indeed, while the expectation that the nonmedical use of prescription drugs for cognitive enhancement (NMUPD-CE) improves one’s capacities or helps in coping with strain seems widespread (DeSantis et al., 2008; Vargo & Petróczi, 2016; Zohny, 2015), the users of such drugs risk side effects. These side effects include headaches, insomnia, hypertension, addiction, or personality changes (Winder-Rhodes et al., 2010).

Not only have the concerns about side effects sparked ethical debates. Scholars are also apprehensive about the potential costs for the healthcare system, indirect pressure to use such drugs to keep up with others, and unfair advantages if some people engage in the NMUPD-CE to compete for personal gain (Racine et al., 2021; Dubljević, 2014; Greely et al., 2008; Schleim & Quednow, 2017).

While this debate is ongoing, we still do not know the exact prevalence of the use of NMUPD-CE in the general population. Existing prevalence rates estimates vary greatly across studies. Comparisons between studies are difficult due to different populations researched, definitions applied for NMUPD-CE, and measures used (Sattler, 2016; Smith & Farah, 2011). For example, a large-scale, online cross-sectional study with a non-random sample via media outlets in 15 western countries found the United States to have the highest self-reported 12-month prevalence for NMUPD-CE (2015: 18.7%; 2017: 21.6%) (Maier et al., 2018). This study also found that the prevalence increased in almost all countries during the observation period, although different participants were investigated during the two time points and the results might reflect a self-selected sample. In Germany, the country in which we conducted our study, the prevalence increased but from a much lower baseline; it was 1.5% in 2015 and 3.0% in 2017.

The findings from the aforementioned international study lie in the range of prevalence data from other studies on the general and working population in Germany. Different methodologies (partially including other substances than prescription drugs) revealed a life-time prevalence rate varying between 1.5% and 12.1% (DAK, 2009; Hoebel et al., 2011; Marschall et al., 2015; Sattler & Schunck, 2016). However, respondents’ willingness to use drugs for cognitive enhancement seems to generally exceed the prevalence (Marschall et al., 2015; Sattler & Schunck, 2016). Possible reasons include lower sensitivity of willingness measures, but also not everyone willing to use them might have had an opportunity or access to the drugs.

While research on this topic is gaining traction, the etiology behind NMUPD-CE among employees has hardly been investigated. However, first research in students provides evidence for a relationship between strain and the nonmedical use of prescription drugs for cognitive enhancement (NMUPD-CE) (e.g., Ponnet et al., 2015; Sattler, 2019). Still, only few studies have investigated this phenomenon in the working population (e.g., Schröder et al., 2015; Wiegel et al., 2016). Existing research on the relationship with stress has been criticized. The criticism spans fromresearch that is mainly descriptive or correlational, to an “improper temporal ordering of measures (e.g., correlating stress levels measured over a period of 12 months with lifetime drug use)”, to the use of convenience samples (Sattler, 2019, 2). Moreover, studies commonly lack a theoretical background or do not consider more complex mediating and moderating processes between stressors, individual resources, strain, and NMUPD-CE. Thus, prevention and intervention strategies lack valid information about the causes of NMUPD-CE.

Therefore, this paper aims to add to the theory-guided research on stressor-related influences on the use of NMUPD-CE. Thereby, this paper tests how different job demands and resources influence an employee’s experience of strain. Based on a modified version of the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al., 2001), we examined how these factors directly and indirectly affect the willingness to cope with strain by instrumentalizing prescription drugs for enhancement. We used a large-scale, randomly selected sample of employees in Germany to improve our understanding of this phenomenon.

A Modified Job Demands-Resources Model to Understand the Nonmedical Use of Prescription Drugs for Cognitive Enhancement

The JD-R model is an influential model that explains the interplay and effects of conditions in the workplace on different outcomes such as burnout, poor health, sickness, absence, weak performance, or substance use (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014; Crawford et al., 2010; Demerouti et al., 2001; Schaufeli, 2017; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). These conditions at work can be objective demands (i.e., stressors) or subjective strain (i.e., perceived stress). Social, organizational, and personal resources are also considered in the JD-R model. The model is flexible and dynamic in nature, in that it is adaptable to other problems (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014) and has been validated both with cross-sectional (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014; Schaufeli, 2017) and longitudinal data (Brauchli et al., 2013; Schaufeli et al., 2009; Upadyaya et al., 2016).

We adapt the model by incorporating strain as a consequence of demands (cf. Schaufeli & Taris, 2014) to better understand variation in employees’ willingness for the NMUPD-CE (see Fig. 1). We expect that demands affect NMUPD-CE – at least partly mediated via strain – whereas resources buffer the effects of demands on strain. Resources are also expected to extert indirect effects on NMUPD-CE via strain as well as direct effects. In the following, we will elaborate on this model, its predictions, and relevant evidence.

An Adapted Job Demands-Resources Model to Understand Willingness to Engage in Nonmedical Use of Prescription Drugs for Cognitive Enhancement. Notes: Each arrow refers to one of the hypotheses (H) described in the text. Signs in parentheses indicate the expected direction of the effect. The italicized hypotheses denote mediation effects of demands (H4) and resources (H7) on the nonmedical use of prescription drugs for cognitive enhancement via strain

Demands include physical, social, or organizational aspects of a jobFootnote 1 such as long working hours, shift work, emotional demands, job insecurity, or leadership responsibility (Demerouti et al., 2001; Hu et al., 2011; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014).Footnote 2 Prior research suggests positive associations between demands like working hard, highly consequential work, and NMUPD for enhancing cognition or mood (Marschall et al., 2015). Moreover, NMUPD-CE was connected to the exposure to psychological demands, the quantitative extent of work requirements, shift work, job insecurity, poor labor market opportunities, and experiencing negative workdays (Schröder et al., 2015). A negative work atmosphere increased the risk of taking prescription drugs (e.g., antidepressants, benzodiazepines, analgesics, and stimulants) (Traweger et al., 2004), although this study did not focus on enhancement purposes.

The effect of demands on NMUPD-CE can be understood by considering the empirically well-supported effects of the types of demands on different indicators of strain (e.g., fatigue, irritability, or exhaustion) (Pluut et al., 2018; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014; Schröder et al., 2015). For example, workload and emotional demands are related to burnout (Vander Elst et al., 2016), while job insecurity is associated with distress and strain (De Witte et al., 2016). Conversely, supervisors may have greater responsibilities, pressure, and workload, but they may perceive less stress due to greater control of their work (Sherman et al., 2012). Demands can act as stressors and cause strain (Hockey, 1997; Schaufeli et al., 2009) because increasing demands require additional compensatory mental effort to maintain a consistent performance level. The physiological and psychological costs of more effort can manifest as strain (Bakker et al., 2003b).

People respond to demands and strain differently. For example, they may avoid the stressor (Stephenson et al., 2016). Others may use different coping methods with the intention of maintaining high performance levels. This can be done by managing the demands (e.g., busy schedules) to reduce the associated costs of the extra effort (e.g., mental capacity) or to counteract strain and its negative consequences (Maier et al., 2015; Riddell et al., 2018; Wolff et al., 2014). Using NMUPD-CE drugs with the perceived possibility of increasing or maintaining alertness, concentration, and wakefulness are such coping methods. Thus, in line with the self-medication hypothesis and drug instrumentalization theory, individuals instrumentalize drugs while accepting or ignoring associated health-risks (Khantzian, 1997; Müller & Schumann, 2011; Sattler & Wiegel, 2013).

Research descriptively exploring employees’ reasons for using NMUPD-CE suggests instrumental motivations, which can be interpreted as reactions to demands and strain. These motives can take the form of wanting to be able to relax after a stressful day at work, enhancing one’s cognitive ability, improving sleep, easing and keeping up with the workload, and/or having enough energy for private life (Maier et al., 2016; Marschall et al., 2015; Schröder et al., 2015). Some of the motives seem to target strain, while others more directly refer to dealing with upstream demands. Therefore, job performance maintenance under increasingly demanding and strain-inducing situations as well as enhancement are a relevant motive for NMPUD-CE. Moreover, qualitative interviews with users in highly demanding jobs support the instrumentalization argument (Schröder et al., 2015). Correlational research in different populations including employees and students suggests a positive relationship between frequent or chronic stress and NMUPD-CE (Maier et al., 2015; Sattler, 2019). Work-related stress was also associated with higher NMUPD-CE willingness (Wiegel et al., 2016).

Despite robust patterns between demands and NMUPD-CE, some studies found no statistically significant relationship between demands such as time pressure (Maier et al., 2015), temporary contracts, or more working hours (Marschall et al., 2015) and NMUPD-CE. One study even found a negative association with leadership responsibility (Marschall et al., 2015). While we know of no studies on NMUPD-CE that investigated the mediating effects of strain, some included demand and strain measures simultaneously (Maier et al., 2015). Some studies on other substances indicated that strain might be the mechanism behind the positive relationship between demands and substance use (Barnes & Zimmerman, 2013; Wiesner et al., 2005).

Although strain might be an important mediator, we still expect an additional direct effect of demands on NMUPD-CE willingness. This direct effect might be due to employees trying to manage demands to prevent strain, for example, by foreseeing the negative consequences of demands, meeting the needs or pressures of a demanding job, or ensuring sufficient performance (Hockey, 1997).

Next to demands and strain, resources for a job are another important constituent of the JD-R model. Resources can either be internal (i.e., cognitive features or action patterns such as emotional stabilityFootnote 3) or external (e.g., job autonomy, instrumental, or emotional social support) (Crawford et al., 2010; Schaufeli et al., 2009; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Because resources foster work engagement and motivation (Crawford et al., 2010; Demerouti et al., 2001; Schaufeli, 2017), it can be assumed that employees with high resources show higher intrinsic work motivation. Employees with more resources and higher intrinsic work motivation might be less likely to engage in NMUPD-CE use since doing so might undermine the sense of personal achievement and satisfaction from mastering tasks (cf. Midgley & Urdan, 2001). Moreover, sufficient resources enable the achievement of life goals, coping with problems, or general well-being (Wiegel et al., 2016). Conversely, employees with insufficient resources might search for NMUPD-CE to instrumentally compensate for these deficiencies.

Few studies have investigated the direct effects of resources in the job context. While some studies found no associations of NMUPD-CE with resources such as social support by colleagues, leadership quality, or decision-making power (Schröder et al., 2015), some found negative associations (Wiegel et al., 2016). Moreover, some studies on other substances supported a direct link between substance use and resources (Zhang & Snizek, 2003), while others found no support but assumed that an indirect effect via strain explains this connection better (Peck et al., 2018; Sapp et al., 2010).

Resources can protect from strain by reducing health impairment and burnout (Bakker et al., 2010a, b; Crawford et al., 2010; Vander Elst et al., 2016) and therefore increase well-being. For example, social support is not only activated when strain is high, but it helps individuals to experience less strain a priori (Viswesvaran et al., 1999). Resources have been found to lower exhaustion-type strain (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014), and also other negative outcomes of demands such as burnout (Brauchli et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2011; Schaufeli, 2017).

Moreover, resources can help in challenging situations and mitigate the effect of demands on strain by bufferingthe effects of demands as stress coping methods (Vander Elst et al., 2016; Tadić et al., 2015; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014; Pomaki et al., 2010). Findings for this moderating role of resources are mixed (Schaufeli, 2017). For example, it was found that certain resources mitigate the impact of job demands on strain and burnout (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014; Bakker et al., 2010b; Jonge & Dormann, 2006; Vander Elst et al., 2016; Viswesvaran et al., 1999). However, other studies reveal only small (Hu et al., 2011; Pomaki et al., 2010; Tadić et al., 2015) or no buffering effects (Bakker et al., 2004; Crawford et al., 2010). Some argue that this is due to suboptimal measurements (Hu et al., 2011) or because the primary role of resources is the direct reduction of strain rather than alleviating the effects of demands with strain (Viswesvaran et al., 1999). Thus, further research is needed.

In sum, we predict that:

-

(H1) Demands are positively associated with the NMUPD-CE willingness.

-

(H2) Demands are positively associated with strain.

-

(H3) Strain is positively associated with the NMUPD-CE willingness.

-

(H4) Demand effects are partially mediated by strain.

-

(H5) Resources are negatively associated with the NMUPD-CE willingness.

-

(H6) Resources are negatively associated with strain.

-

(H7) Effects of resources on the NMUPD-CE willingness are partially mediated by strain.

-

(H8) Resources reduce the positive association between demands and strain.

Methods

Data and Population

We used data from the first wave of the Linked Employer-Employee Panel Survey (LEEP-B3) (Diewald et al., 2014). The data were collected via computer-assisted telephone interviews among employees in Germany who were subject to social security contribution (i.e., the majority of employees in Germany) and who were working in large firms (minimum 500 employees). This sampling frame only excluded self-employed, marginally employed, apprentices, civil servants, and all employees of smaller companies. From the net sample (21,678), a total sample of 6454 individuals (response rate: 29.77%) were interviewed. Selectivity analyses with German registry data indicate a generally good representation of the underlying population, but a slight overrepresentation of German nationals and workers in the information and communication sector, and a slight underrepresentation of people with lower education and those working in very large organizations (Diewald et al., 2014). The study and all procedures have been approved by the security officer of the Federal Institute for Employment Research and the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (see detailed Ethics Statement in Appendix 1).

Measures

Willingness to Use Prescription Drugs Nonmedically for Cognitive Enhancement

Respondents indicated their willingness to use prescription drugs to support their cognitive abilities (e.g., for increasing concentration, memory, or vigilance) without medical necessity with the response options “No, I would never/under any circumstances do this (again)” (0) or “Yes, I would do it (again) under certain circumstances” (1) (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics of this and other variables; cf. Wiegel et al., 2016). Such measures of willingness have several advantages: they deliver insights about relatively new phenomena (which is the case for NMUPD-CE) and they can be used to explore trends (Farah et al., 2004; Sattler & Schunck, 2016). They are also frequently used to investigate substance use and misuse as proximal antecedents of future behaviour (Gibbons et al., 1998b) since they show high correlations with behaviour (Beck & Ajzen, 1991) but avoid problems of causal ordering in cross-sectional data that use prior behaviour as a dependent variable.Footnote 4 Moreover, they are less sensitive than asking about prior deviant behaviour and fewer refusals or inaccurate answers can be expected (Gibbons et al., 1998a, b). In our case, only 122 answers (1.89%) were missing. We ran multilevel models to examine the variation of willingness of NMUPD-CE across occupations (ISCO-08), organizations and branches, but found only very little intraclass-correlations (ICCoccupations < 0.001, ICCorganizations = 0.002, ICCbranches < 0.001). Thus, we do not elaborate further on this.

Strain

Strain was assessed using the work-family conflict subscale for strain-based conflict (Carlson et al., 2000). This strain measure captures interrole conflicts produced by the incompatibility of demands in work and private life (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985) represented by three items (exemplary item: “Due to all the pressures at work, sometimes when I come home, I am too stressed to do the things I enjoy.”). Response options ranged from “does not apply at all” (1) to “applies completely” (5). Cronbach’s α was 0.78 and responses were averaged. According to Matthews et al. (2010), a shorter version of the initial scale is sufficiently valid and reliable, and replicates the results of the long version.

Demands

Agreed working time (per week) and overtime (as the difference between agreed and actual working time per week) measured the workload.

Shift work defined as non-standard working hours was assessed by asking whether the respondents’ work schedules include shift work (no/yes) and if yes, how often (sometimes/regularly/always). We recoded “no” and “sometimes” answers into (0) and all other responses into (1).

Emotional demands were assessed using two questions on how often employees have felt wrongly criticized or harassed by either colleagues or supervisors. Response options ranged from “never” (1) to “always” (5). Responses were averaged (Cronbach’s α = 0.61).

Job insecurity was measured through the averaged values of two questions about the perceived likelihood of losing the job within two years (with response options “very unlikely” (1) to “very likely” (5)) and long-term employment security granted by the employer (“fully granted” (1) to “not at all granted” (5); Cronbach’s α = 0.651).

Leadership responsibility was assessed by asking: “In your position at work, do you supervise others, such as a team, a larger group, or part of the business?” and response options “no” (0) or “yes” (1).

Resources

Emotional stability, defined as a tendency to not experience negative emotions such as anxiety and depression (Caspi, 1998; Terracciano et al., 2008), was measured with three items (exemplary item: “I see myself as someone who is relaxed and handles stress well.”; response options: “I do not agree at all” (1) to “I agree entirely” (5)) that were averaged (Cronbach’s α = 0.54) (Gerlitz & Schupp, 2005; Rammstedt & John, 2005).

Job autonomy was measured on three dimensions: schedule, method, and work criteria autonomy (Breaugh, 1985) with one question per dimension (exemplary item: “Within my working hours I have control over the sequencing of my work activities.”; response options: “not correct at all” (1) to “fully correct” (5)). Responses were averaged (Cronbach’s α = 0.71).

Emotional social support was measured with an adapted Burt-Generator (Burt, 1984) by asking respondents about the number of people they can share personal thoughts and feelings with or talk about things they do not typically share with everyone, excluding their partner.

Instrumental social support captured support by the supervisor and by colleagues (with one question each) in reconciling responsibilities from work and private life. Response options ranged from “not correct at all” (1) to “fully correct” (5). Responses were averaged (Cronbach’s α = 0.40).

Covariates

Evidence on sex differences in NMUPD-CE is inconclusive in indicating higher engagement of men, women, or no differences at all (Marschall et al., 2015; Sattler & Schunck, 2016; Schröder et al., 2015; Wiegel et al., 2016), and this also applies for responses to strain and substance use (Sattler, 2019; Slopen et al., 2011). Men were coded “0” and women “1”.

Age-effects for NMUPD-CE are also heterogenous (Marschall et al., 2015; Sattler & Schunck, 2016; Schröder et al., 2015; Wiegel et al., 2016). However, cognitive stress and mental health may vary with age and so do reactions to stressors or demands (Antoniou et al., 2006). Age was assessed in years.

Education (in years) and income (i.e. personal gross monthly earnings in euro) served as controls for socio-economic background. Studies have found that stress varies with socio-economic background (Damaske et al., 2016; Kunz-Ebrecht et al., 2004; Lunau et al., 2015), while results for associations with substance use are inconclusive (Frone, 2006; Marschall et al., 2015; Sattler & Schunck, 2016). However, better access to NMUPD-CE has been assumed for individuals with more income, and more knowledge about NMUPD-CE is expected with higher education (Sahakian et al., 2015; Sattler et al., 2013).

Statistical Analysis

As with many other tests of the JD-R model (Bakker et al., 2003a; b; Hu et al., 2011), we estimated direct, indirect, and total effects in Structural Equation Models (with Stata/MP, version 14.2) to assess the relationship between the various job demands, resources, and NMUPD-CE willingness with strain as a mediator. Such models are useful tools for testing causal claims (Fox, 2002; Pearl, 2012) and mediation analysis in comparison to the “three-regressions” approach proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986; see Iacobucci et al., 2007).

Our major outcome variable (NMUPD-CE) was a binary variable that is frequently analysed with non-linear probability models (NLPM), while the linear probability models that we used here can be interpreted more straightforwardly and avoid the problems of NLPM (Breen et al., 2018; Kupek, 2005).Footnote 5 We used bias-corrected bootstrapping with 1000 replications as a common strategy for handling binary outcome variables in structural equation modeling which produces similar results as other strategies (Bollen & Stine, 1992). In addition, bootstrapping techniques are useful in dealing with biases in mediation analysis using categorical and non-normally distributed data (Finney & DiStefano, 2006; MacKinnon et al., 2004).

Due to missing information on all variables (e.g., because of the sensitivity of NMUPD-CE), we used a Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) approach. It often delivers similar results as imputation techniques (Collins et al., 2001).

As suggested by MacKinnon et al. (2004), we reported direct, indirect and total effects of the mediation. To test interaction effects and ease their interpretation, all non-binary variables were mean-centered. For these tests, all possible interactions between each demand and each resource on strain or NMUPD-CE were tested step-wise (available upon request), while only interactions with p < 0.05 are shown in the final model. Generally, significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Descriptively, we see that more than every tenth respondent (10.47%) is willing to use prescription drugs for nonmedical enhancement (see Table 1). Based on the Structural Equation Models, column 2 in Table 2 shows that agreed working time, overtime, shift work, emotional demands, job insecurity, leadership responsibility (i.e. all demands), are positively associated with the mediator strain (supporting H2), whereas emotional stability, job autonomy, emotional and instrumental social support (i.e. all resources), show negative associations with strain (supporting H6). Moreover, women, older respondents, and those with higher education reported more strain. Income was unrelated to strain.

Column 3 shows that strain has a positive direct effect on the NMUPD-CE willingness (supporting H3). Emotional demands are the only demand-variable with a statistically significant positive direct effect (thus, support for H1 is weak). An increase by one standard deviation increases the probability that respondents report an NMUPD-CE willingness by 1.31%. Surprisingly, overtime shows an unexpected negative direct effect. Emotional stability is the only resource that directly reduces the NMUPD-CE willingness (thus, indicating weak support for H5). The control variables show no direct effect.

Column 4 reveals that all demands indirectly increase the NMUPD-CE willingness through increasing strain (supporting H4); the indirect effect for emotional demands accounts for 22% of total effects and 22% for job insecurity.Footnote 6 All resources show indirect negative effects through strain (supporting H7); the indirect effect of emotional stability accounts for 32% of the total effect. Being a woman, higher in age, and higher in education also increase the NMUPD-CE willingness via strain.

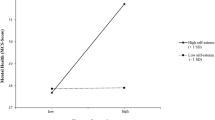

Table 3 shows two statistically significant negative interaction effects between demands and resources on the mediating variable strain (revealing limited support for H8); emotional stability seems to slightly buffer the effects of overtime and leadership responsibility on strain, while more neurotic respondents report more strain the more overtime hours they work. When including these interaction effects, the other effects seem to be hardly affected. We also explored direct interaction effects on NMUPD-CE willingness but found no such effects.

Discussion

Summary and Interpretation

While the work environment has changed in recent decades and strain levels as well as mental health problems have increased (Brühl & Sahakian, 2016; Fink, 2016; Siegrist, 2016; Tecco et al., 2013), the causality between these changes in the working population is not sufficiently understood. The use and misuse of substances including alcohol is a known coping strategy for strain (Frone, 2016; Ruisoto et al., 2017; Unrath et al., 2012). However, little is known about NMUPD-CE among employees, although first evidence on NMUPD-CE in the workplace exists (Maier et al., 2018; Schröder et al., 2015).

This study used data from a large representative sample of employees in Germany to investigate the antecedents of NMUPD-CE based on assumptions of the JD-R model. We show that individuals with high job demands and low resources experience more strain, whereby certain resources buffer the effects of demands. Strain partially mediated the effects of the demands on NMUPD-CE, while several direct effects of demands and resources remained. By uncovering these mechanisms behind the decision for or against NMUPD-CE among employees this study adds valuable information to the existing literature. Additionally, it replicates the core findings of the JD-R model and successfully introduced it to the NMUPD-CE literature. Appendix Table 6 provides a summary of the findings.

In line with prior research (De Witte et al., 2016; Pluut et al., 2018; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014; Vander Elst et al., 2016), we show that all job demands (i.e., agreed working time, overtime, shift work, emotional demands, job insecurity, and leadership responsibility) directly increased the strain level of employees (H2). This finding also highlights the diverse nature of stressors employees face, and it underlines that job dissatisfaction, mental and physical health problems, absenteeism, or productivity losses can have different origins (Barnes & Zimmerman, 2013; Siegrist, 2016; Tecco et al., 2013).

Strain was associated with an elevated NMUPD-CE willingness (H3). This is in accordance with the assumption and empirical findings that students and employees risk health impairments by utilizing NMUPD-CE to cope with strain (Sattler, 2019; Wiegel et al., 2016). However, only emotional demands were directly associated with a higher NMUPD-CE willingness – providing limited support for H1. Also, prior research is ambiguous regarding such direct demand-effects (Maier et al., 2015; Marschall et al., 2015; Schröder et al., 2015). One interpretation is that research needs to consider subjective assessments of stress in addition to or instead of objective measures, as individuals cognitively appraise stressors in various ways (Agnew, 2013; Barbieri & Connell, 2017; LeBlanc, 2009; Sattler, 2019). That is, identical stressors can be perceived differently across individuals and thus bear different consequences. There are also indications that subjective measures are more precise and meaningful in predictions models (Agnew, 2013; Barbieri & Connell, 2017). Our results suggest that respondents who perceive more stress hope that NMUPD-CE is sufficient to help them cope with their strain and therefore increase or maintain their cognitive performance. This aligns with descriptive research on the motives of NMUPD-CE users (Maier et al., 2016; Marschall et al., 2015; Schröder et al., 2015), and also research showing that such drug use can in fact increase cognitive performance (Caviola & Faber, 2015).

In support of H4, our study shows that all demands have an indirect positive relationship via strain with the NMUPD-CE willingness. Thus far, no study has examined a potential mediating effect of strain between demands and NMUPD-CE. Our finding, therefore, provides a better understanding of how demands and strain are related to NMUPD-CE, but also shows that demands need to be subjectively experienced as strenuous to cause an effect, as explained previously. The only unexpected exception is an inverse relationship between overtime and the NMUPD-CE willingness. However, one reason for this might be that working overtime is an alternative method to achieve work goals without the use of external help such as substances.

We were able to replicate a common finding that internal (i.e., emotional stability) and external resources (i.e., job autonomy, emotional and instrumental social support) can directly reduce the effects of demands on strain (H6; Brauchli et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2011; Schaufeli, 2017; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). But there was only limited support for a demand-buffering effect of resources on strain (H8). This is also in line with prior research (Crawford et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2011; Tadić et al., 2015; Wiegel et al., 2016). Out of 24 possible interaction effects, only emotional stability seems to buffer the negative effects of working hours and leadership responsibility.

Additionally, emotional stability was the only resource revealing the expected direct negative association with NMUPD-CE (H5), which adds to prior mixed results on direct resource effects (Schröder et al., 2015; Wiegel et al., 2016). Thus, emotional stability can especially be seen as a personal resource that seems to go along with the experience of fewer stressors to begin with (Bakker et al., 2010b; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014) and to lower the susceptability to strains such as work-family conflict (Allen et al., 2012). It also affects the reactions to stressful events as a resource (acting as a buffer) and offers a direct protection from NMUPD-CE (Sattler & Schunck, 2016). Therefore, emotional stability serves as a highly relevant coping resource in the complex interplay of stressors (Gunthert et al., 1999; Schneider, 2004; Schneider et al., 2012), their immediate perception, and downstream effects such as substance use. This might be explained by the fact that individuals with high emotional stability are less likely to refer to an automatic mode of self-regulation when facing environmental stimuli such as stress (Turiano et al., 2012). Thus, their stress-response might be less focused on behaviour that they would expect to help them deal with stress. Conversely, this implies that low emotional stability is a risk factor for substance misuse including NMUPD-CE, because these substances might be perceived as offering prompt relief when under stress or seeking performance improvements (Benotsch et al., 2013). Our findings regarding the effects of emotional stability, therefore, underline the importance of personality traits in predicting health-related behaviours (Lahey, 2009; Turiano et al., 2012).

Moreover, when strain is considered as a mediator between resources and NMUPD-CE, all resources show the expected inverse relation, supporting H7. Thus, these results imply that with a scarcity of resources, NMUPD-CE might be viewed as a way to compensate for the deficiency, whereas having sufficient resources can protect from experiencing strain by aiding in mastering challenging situations and mitigating the effects of stressors on strain (Pomaki et al., 2010; Sattler, 2019; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014; Tadić et al., 2015; Vander Elst et al., 2016; Wiegel et al., 2016).

In sum, we showed that the JD-R model, which was originally developed to explain burnout among employees, is a useful and flexible framework to apply to employees’ NMUPD-CE use. The model helps to better understand the drivers and obstacles of NMUPD-CE, namely the interplay between objective demands, its subjective consequences (i.e. strain), and personal, social, or organizational resources, as well as the mediating role of strain linking effects of demands and resources to this type of substance use and misuse.

Strengths, Limitations, and Further Research

Our study advances prior research on NMUPD-CE in the work context in several dimensions. While earlier research in this field lacks theoretical foundations and is descriptive (e.g., Schröder et al., 2015), this is the first study on NMUPD-CE in employees that implements the JD-R model, enriched with assumptions from research on coping strategies (Brougham et al., 2009; Stephenson et al., 2016), drug instrumentalization theory (Müller & Schumann, 2011), and the self-medication hypothesis (Khantzian, 1997).

While literature reviews on NMUPD-CE (Sattler, 2016; Smith & Farah, 2011) highlight that most studies in the field use small and/or convenience samples potentially suffering from self-selection or specific subgroups of employees (Franke et al., 2013; Maier et al., 2018; Schröder et al., 2015; Wiegel et al., 2016), our analysis relied on a representative sample of employees in Germany working for companies with over 500 employees covering a broad range of occupations and sectors (Abendroth et al., 2014). This large and heterogenous sample is also an advantage over numerous other studies employing the JD-R model in various contexts (Vander Elst et al., 2016; Tadić et al., 2015). However, future research might be extended to smaller firms and to the international context since demands and resources might be perceived differently due to varying lifestyles or work norms, and also because national drug regulations and prescribing behaviour of physicians are different (Sattler & Schunck, 2016).

Though we assessed various demands and resources that can be found in almost every job (including internal resources, which is not yet common in JD-R applications) (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014), future research may extend our coverage. Candidate factors are, for example, resources such as resilience (i.e. the ability to easily adapt and cope with stressful or traumatic events and strain) (Ghimbuluţ et al., 2012; Oshio et al., 2018) or new potential demands such as choice overload from digitalized work environments (Zeike et al., 2019).

Our analysis relied on cross-sectional data, whereas future studies should engage panel data to better establish the causal order of the examined variables. However, we do not correlate prior NMUPD-CE with current demands, strain, and resources which is particularly prone to biased results due to an improper causal ordering. Instead, we applied a frequently used strategy to investigate substance use and misuse by assessing respondents’ willingness as a proximal antecedent of future behaviour (Gibbons et al., 1998b). Willlingness showed high correlations with current behaviour (Beck & Ajzen, 1991; Gibbons et al., 1998a, b). Still, this is a self-reported measure and we cannot rule out social desirability bias (Chen et al., 2015; Roche et al., 2008; Wolff et al., 2014), although such measures are less sensitive than prior behaviour (Gibbons et al., 1998a, b). For example, we found hardly any item non-response (1.89%). Willingness measures also have the advantage of providing insights for NMUPD-CE as a relatively new behaviour and can thereby help to identify possible trends (Wiegel et al., 2016).

Conclusion

Our study shows that high job demands and low resources increase strain, while certain resources buffer the effects of demands. To deal with this strain and to maintain or enhance work performance, some employees are willing to instrumentalize prescription drugs without medical need. Some of the findings resemble those on the use of other substances including alcohol (Frone, 2016).

However, it can be argued that NMUPD-CE is somewhat different in nature. While alcohol might mainly be used to divert from or reduce strain, NMUPD-CE might be a strategy to enhance cognitive performance more directly or to reduce the potential performance-diminishing effects of strain. Thus, it might “be understood as a non-addictive, functional adaption to complex, competitive, fast-changing modern microenvironments by increasing, sustaining, or restoring work performance” (Wiegel et al., 2016, 111). But employees still risk side effects and long-term health consequences by engaging in such behaviour that has been also considered unfair (Dubljević, 2014; Greely et al., 2008; Schleim & Quednow, 2017).

Prevention and intervention strategies might be informed by our findings. First, employers may monitor individual and company-wide demands and resources by using surveys or online tools (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014; Schaufeli, 2017; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Then, workshops, trainings, or structural changes and regulations might be implemented to decrease employees’ demands along their strain-inducing effects. Moreover, employers’, physicians’, and at-risk individuals’ awareness should be raised that certain personality traits (such as neuroticism) can be risk factors for unhealthy behaviour, but that certain resources can also mitigate these risks (e.g., active strain management, resilience training, or job crafting).

While this might not only reduce strain and ultimately NMUPD-CE, such approaches would be generally valuable since a healthier work environment with resourceful employees has manifold positive impacts. This includes higher work performance and increased well-being, less absenteeism, and fewer work accidents (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014; Barnes & Zimmerman, 2013; Siegrist, 2016; Tecco et al., 2013). Furthermore, information for employees and managers regarding the potential non-sustainable, health-endangering, and counterproductive effects of NMUPD-CE might be distributed. Thus, politicians and employers can start now to actively create a resourceful work environment with fewer negative repercussions of job demands.

Data Availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to data restrictions by the Federal Institute for Employment Research (Institut für Arbeitsmarkt und Berufsforschung (IAB). Data are only available on request for analyses to be conducted locally at Bielefeld University.

Notes

Demands can be clustered into 1) hindrance demands, e.g., shift work, which hinder personal growth and 2) challenge demands, e.g., responsibility, that can lead to personal growth. However, this distinction is not often made (Crawford et al., 2010).

Physical demands that are often considered will be excluded here, because they are not assumed to influence NMUPD-CE.

A recent literature review on the JD-R model identified indicators of emotional stability as personal resources that can affect the perception of job characteristics and thereby impact job satisfaction and performance (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014).

Despite the causality problems, we also estimated a model with a 12-month prevalence measure of the NMUPD-CE (see Appendix Tables 4 and 5). It reveals a statistically significant direct positive effect of higher strain on this prevalence. Higher emotional demands are, however, surprisingly negatively associated to this prevalence, whereby no association was found for overtime and emotional stability. However, all indirect effects via strain from the NMUPD-CE willingness model were also found. In the interaction model, we found the two interaction effects from the NMUPD-CE willingness model and an unexpected direct positive interaction effect of agreed working time and emotional stability on the prevalence. Moreover, the direct negative association of the NMUPD-CE with education becomes significant.

Robustness of the results was tested in various ways (available upon request): bootstrapped estimations are similar to those without bootstrapping. To consider the difficulty of handling dichotomous dependent variables in structural equation modelling, we estimated generalized structural equation modelling, different logistic, firthlogit, and linear probability multivariate regressions models, which produced the same conclusions. Alternative operationalization of variables (i.e., agreed working time categorized in “part-time” vs. “full-time”; overtime measured using six categories ranging from “daily” to “never”; and emotional social support measured as “no” vs. “at least one person to talk to”; the frequency of shift-work with four categories; the total number of persons for whom one is responsible) or using another strain-measure (time-pressure) also suggested similar results.

The proportion of mediation is only reported if indirect and total effects are statistically significant and not inconsistent.

References

Abendroth, A., Melzer, S. M., & Jacobebbinghaus, P. (2014). Methodological Report Employee and Partner Surveys of the Linked Employer- Employee Panel (LEEP-B3) in Project B3 ‘Interactions Between Capabilities in Work and Private Life: A Study of Employees in Different Work Organizations.’ SFB 882 Technical Report Series 12. Bielefeld.

Agnew, R. (2013). When criminal coping is likely: An extension of general Strain theory. Deviant Behavior, 34, 653–670.

Allen, T. D., Johnson, R. C., Saboe, K. N., Cho, E., Dumani, S., & Evans, S. (2012). Dispositional variables and work–family conflict: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 17–26.

Antoniou, A.-S., Polychroni, F., & Vlachakis, A. N. (2006). Gender and age differences in occupational stress and professional burnout between primary and high-school teachers in Greece. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21, 682–690.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands-resources theory. In C. L. Cooper (Ed.), Wellbeing (pp. 1–28). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd..

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., de Boer, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2003a). Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62, 341–356.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., Taris, T. W., Schaufeli, W. B., & Schreurs, P. J. G. (2003b). A multigroup analysis of the job demands-resources model in four home care organizations. International Journal of Stress Management, 10, 16–38.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management, 43, 83–104.

Bakker, A. B., Boyd, C. M., Dollard, M., Gillespie, N., Winefield, A. H., & Stough, C. (2010a). The role of personality in the job demands-resources model: A study of Australian academic staff. Career Development International, 15, 622–636.

Bakker, A. B., van Veldhoven, M., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2010b). Beyond the demand-control model: Thriving on high job demands and resources. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 9, 3–16.

Barbieri, N., & Connell, N. M. (2017). Examining general Strain: Using subjective and objective measures of academic Strain to predict delinquency. Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice, 15, 330–348.

Barnes, A. J., & Zimmerman, F. J. (2013). Associations of occupational attributes and excessive drinking. Social Science & Medicine, 92, 35–42.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Beck, L., & Ajzen, I. (1991). Predicting dishonest actions using the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Research in Personality, 25, 285–301.

Benotsch, E. G., Jeffers, A. J., Snipes, D. J., Martin, A. M., & Koester, S. (2013). The five factor model of personality and the non-medical use of prescription drugs: Associations in a young adult sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 55, 852–855.

Bollen, K. A., & Stine, R. A. (1992). Bootstrapping goodness-of-fit measures in structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research, 21, 205–229.

Brand, S., Ebner, K., Mikoteit, T., Lejri, I., Gerber, M., Beck, J., Holsboer-Trachsler, E., & Eckert, A. (2020). Influence of regular physical activity on mitochondrial activity and symptoms of burnout—An interventional pilot study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9, 667.

Brauchli, R., Schaufeli, W. B., Jenny, G. J., Füllemann, D., & Bauer, G. F. (2013). Disentangling stability and change in job resources, job demands, and employee well-being — A three-wave study on the job-demands resources model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83, 117–129.

Breaugh, J. A. (1985). The measurement of work autonomy. Human Relations, 38, 551–570.

Breen, R., Karlson, K. B., & Holm, A. (2018). Interpreting and understanding logits, Probits, and other nonlinear probability models. Annual Review of Sociology, 44, 39–54.

Brougham, R. R., Zail, C. M., Mendoza, C. M., & Miller, J. R. (2009). Stress, sex differences, and coping strategies among college students. Current Psychology, 28, 85–97.

Brühl, A. B., & Sahakian, B. J. (2016). Drugs, games, and devices for enhancing cognition: Implications for work and society. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1369, 195–217.

Burt, R. S. (1984). Network items and the general social survey. Social Networks, 6, 293–339.

Carlson, D. S., Michele Kacmar, K., & Williams, L. J. (2000). Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56, 249–276.

Caspi, A. (1998). Personality development across the life course. In W. Damon Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 311–388). Wiley.

Caviola, L., & Faber, N. S. (2015). Pills or push-ups? Effectiveness and public perception of pharmacological and non-pharmacological cognitive enhancement. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1852.

Chen, L.-Y., Crum, R. M., Strain, E. C., Martins, S. S., & Mojtabai, R. (2015). Patterns of concurrent substance use among adolescent nonmedical ADHD stimulant users. Addictive Behaviors, 49, 1–6.

Collins, L. M., Schafer, J. L., & Kam, C.-M. (2001). A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods, 6, 330–351.

Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 834–848.

DAK. (2009). Gesundheitsreport 2009. Analyse Der Arbeitsunfähigkeitsdaten. Schwerpunktthema Doping Am Arbeitsplatz. Berlin/Hamburg: DAK/IGES.

Damaske, S., Zawadzki, M. J., & Smyth, J. M. (2016). Stress at work: Differential experiences of high versus low SES Workers. Social Science & Medicine, 156, 125–133.

De Witte, H., Pienaar, J., & De Cuyper, N. (2016). Review of 30 years of longitudinal studies on the association between job insecurity and health and well-being: Is there causal evidence? Review of longitudinal studies on job insecurity. Australian Psychologist, 51, 18–31.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499–512.

DeSantis, A. D., Webb, E. M., & Noar, S. M. (2008). Illicit use of prescription ADHD medications on a college campus: A multimethodological approach. Journal of American College Health, 57, 315–324.

Diewald, M., Schunck, R., Abendroth, A.-K., Melzer, S. M., Pausch, S., Reimann, M., Andernach, B., & Jacobebbinghaus, P. (2014). The SFB882-B3 linked employer-employee panel survey (LEEP-B3). Schmollers Jahrbuch, 134, 379–389.

Dubljević, V. (2014). Response to Open Peer Commentaries on ‘Prohibition or Coffee Shops: Regulation of Amphetamine and Methylphenidate for Enhancement Use by Healthy Adults. The American Journal of Bioethics, 14, W1–W8.

Farah, M. J., Illes, J., Cook-Deegan, R., Gardner, H., Kandel, E., King, P., Parens, E., Sahakian, B., & Wolpe, P. R. (2004). Neurocognitive enhancement: What can we do and what should we do? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5, 421–425.

Fink, G. (2016). Definitions, mechanisms, and effects outlined: Lessons from anxiety. In G. Fink (Ed.), Handbook of Stress Series Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior (Vol. 1, pp. 3–11).

Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2006). Nonnormal and Categorical Data in Structural Equation Models. In G. R. Hancock & O. Mueller (Eds.), Quantitative Methods in Education and the Behavioral Sciences: Issues, Research, and Teaching. Structural Equation Modeling (pp. 269–314). IAP.

Fox, J. (2002). Structural equation models. Appendix to an R and S-PLUS companion to applied regression.

Franke, A. G., Bagusat, C., Dietz, P., Hoffmann, I., Simon, P., Ulrich, U., & Lieb, K. (2013). Use of illicit and prescription drugs for cognitive or mood enhancement among surgeons. BMC Medicine, 11, 102.

Frone, M. R. (2006). Prevalence and distribution of illicit drug use in the workforce and in the workplace: Findings and implications from a U.S. National Survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 856–869.

Frone, M. R. (2016). Work stress and alcohol use: Developing and testing a biphasic self-medication model. Work and Stress, 30, 374–394.

Gerber, M., Jonsdottir, I. H., Arvidson, E., Lindwall, M., & Lindegård, A. (2015). Promoting graded exercise as a part of multimodal treatment in patients diagnosed with stress-related exhaustion. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24, 1904–1915.

Gerlitz, J. Y., & Schupp, J. ( 2005). Zur Erhebung Der Big-Five-Basierten Persönlichkeitsmerkmale Im SOEP. Dokumentation Der Instrumentenentwicklung BFI-S Auf Basis Des SOEP-Pretests. Research Notes, no. 4.

Ghimbuluţ, O., Raţiu, L., & Opre, A. (2012). Achieving resilience despite emotional instability. Cognition, Brain, Behavior, 16, 465–480.

Gibbons, F., Gerrard, M., Blanton, H., & Russell, D. W. (1998a). Reasoned action and social reaction: Willingness and intention as independent predictors of health risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1164–1180.

Gibbons, F., Gerrard, M., Ouellette, J. A., & Burzette, R. (1998b). Cognitive antecedents to adolescent health risk: Discriminating between behavioral intention and behavioral willingness. Psychology & Health, 13, 319–339.

Greely, H., Sahakian, B., Harris, J., Kessler, R. C., Gazzaniga, M., Campbell, P., & Farah, M. J. (2008). Towards responsible use of cognitive enhancing drugs by the healthy. Nature, 456, 702–705.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. The Academy of Management Review, 10, 76–88.

Gudmundsson, P., Lindwall, M., Gustafson, D. R., Östling, S., Hällström, T., Waern, M., & Skoog, I. (2015). Longitudinal associations between physical activity and depression scores in Swedish women followed 32 years. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 132, 451–458.

Gunthert, K. C., Cohen, L. H., & Armeli, S. (1999). The role of neuroticism in daily stress and coping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1087–1100.

Hockey, G. R. (1997). Compensatory control in the regulation of human performance under stress and high workload; a cognitive-Energetical framework. Biological Psychology, 45, 73–93.

Hoebel, J., Kamtsiuris, P., Lange, C., Müters, S., Schilling, R., & von der Lippe, E. (2011). Ergebnisbericht: KOLIBRI-Studie Zum Konsum Leistungsbeeinflussender Mittel in Alltag Und Freizeit. RKI.

Hu, Q., Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2011). The job demands–resources model: An analysis of additive and joint effects of demands and resources. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79, 181–190.

Iacobucci, D., Saldanha, N., & Deng, X. (2007). A meditation on mediation: Evidence that structural equations models perform better than regressions. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17, 139–153.

Jonge, J., & Dormann, C. (2006). Stressors, resources, and Strain at work: A longitudinal test of the triple-match principle. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1359–1374.

Khantzian, E. J. (1997). The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4, 231–244.

Kunz-Ebrecht, S. R., Kirschbaum, C., & Steptoe, A. (2004). Work stress, socioeconomic status and neuroendocrine activation over the working day. Social Science & Medicine, 58, 1523–1530.

Kupek, E. (2005). Log-linear transformation of binary variables: A suitable input for SEM. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 12, 28–40.

Lahey, B. B. (2009). Public health significance of neuroticism. American Psychologist, 64, 241–256.

LeBlanc, V. R. (2009). The effects of acute stress on performance: Implications for health professions education. Academic Medicine, 84, S25–S33.

Lindegård, A., Jonsdottir, I. H., Börjesson, M., Lindwall, M., & Gerber, M. (2015). Changes in mental health in compliers and non-compliers with physical activity recommendations in patients with stress-related exhaustion. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 1–10.

Lo, C. C., Cheng, T. C., & Howell, R. J. (2014). Problem Drinking’s associations with social structure and mental health care: Race/ethnicity differences. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 46, 233–242.

Lunau, T., Siegrist, J., Dragano, N., & Wahrendorf, M. (2015). The association between education and work stress: Does the policy context matter?” Andrea S. Wiley. PLoS One, 10, e0121573.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128.

Maier, L. J., Haug, S., & Schaub, M. P. (2015). The importance of stress, self-efficacy, and self-medication for pharmacological Neuroenhancement among employees and students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 156, 221–227.

Maier, L. J., Haug, S., & Schaub, M. P. (2016). Prevalence of and motives for pharmacological Neuroenhancement in Switzerland-results from a National Internet Panel: Pharmacological Neuroenhancement. Addiction, 111, 280–295.

Maier, L. J., Ferris, J. A., & Winstock, A. R. (2018). Pharmacological cognitive enhancement among non-ADHD individuals—A cross-sectional study in 15 countries. International Journal of Drug Policy, 58, 104–112.

Marschall, J., Nolting, H-D., Hildebrandt, S., & Sydow, H. (2015). Gesundheitsreport 2015. Analyse Der Arbeitsunfähigkeitsdaten. Update: Doping Am Arbeitsplatz. Berlin/Hamburg: DAK/IGES.

Matthews, R. A., Kath, L. M., & Barnes-Farrell, J. L. (2010). A Short, valid, predictive measure of work–family conflict: Item selection and scale validation. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15, 75–90.

Midgley, C., & Urdan, T. (2001). Academic self-handicapping and achievement goals: A further examination. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26, 61–75.

Müller, C., & Schumann, G. (2011). Drugs as instruments: A new framework for non-addictive psychoactive drug use. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34, 293–310.

Oshio, A., Taku, K., Hirano, M., & Saeed, G. (2018). Resilience and big five personality traits: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 127, 54–60.

Pearl, J. (2012). The causal foundations of structural equation modelling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford Press.

Peck, J. H., Childs, K. K., Jennings, W. G., & Brady, C. M. (2018). General Strain theory, depression, and substance use: Results from a nationally representative, longitudinal sample of White, African-American, and Hispanic adolescents and young adults. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 27, 11–28.

Pluut, H., Ilies, R., Curşeu, P. L., & Liu, Y. (2018). Social support at work and at home: Dual-buffering effects in the work-family conflict process. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 146, 1–13.

Pomaki, G., DeLongis, A., Frey, D., Short, K., & Woehrle, T. (2010). When the going gets tough: Direct, buffering and indirect effects of social support on turnover intention. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 1340–1346.

Ponnet, K., Wouters, E., Walrave, M., Heirman, W., & Van Hal, G. (2015). Predicting students’ intention to use stimulants for academic performance enhancement. Substance Use & Misuse, 50, 275–282.

Racine, E., Sattler, S., & Boehlen, W. (2021). Cognitive Enhancement and Well-Being: Unanswered Questions about Human Psychology and Social Behavior. Science and Engineering Ethics, 27, online first.

Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2005). Kurzversion des big five inventory (BFI-K). Diagnostica, 51, 195–206.

Repantis, D., Schlattmann, P., Laisney, O., & Heuser, I. (2010). Modafinil and methylphenidate for Neuroenhancement in healthy individuals: A systematic review. Pharmacological Research, 62, 187–206.

Riddell, C., Jensen, C., & Carter, O. (2018). Cognitive enhancement and coping in an Australian University student sample. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 2, 63–69.

Roche, A., Pidd, K., Bywood, P., & Freeman, T. (2008). Methamphetamine use among Australian workers and its implications for prevention. Drug and Alcohol Review, 27, 334–341.

Ruisoto, P., Vaca, S. L., López-Goñi, J. J., Cacho, R., & Fernández-Suárez, I. (2017). Gender differences in problematic alcohol consumption in university professors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14, 1069.

Sahakian, B. J., Bruhl, A. B., Cook, J., Killikelly, C., Savulich, G., Piercy, T., Hafizi, S., Perez, J., Fernandez-Egea, E., Suckling, J., & Jones, P. B. (2015). The impact of neuroscience on society: Cognitive enhancement in neuropsychiatric disorders and in healthy people. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B: Biological Sciences, 370, 20140214.

Sapp, A. L., Kawachi, I., Sorensen, G., LaMontagne, A. D., & Subramanian, S. V. (2010). Does workplace social capital buffer the effects of job stress? A cross-sectional, multilevel analysis of cigarette smoking among U.S. manufacturing workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 52, 740–750.

Sattler, S. (2016). Cognitive enhancement in Germany: Prevalence, attitudes, terms, legal status, and the ethics debate. In F. Jotterand & V. Dubljević (Eds.), Cognitive enhancement: Ethical and policy implications in international perspectives (pp. 159–180). OUP.

Sattler, S. (2019). Nonmedical use of prescription drugs for cognitive enhancement as response to chronic stress especially when social support is lacking. Stress and Health, 35, 127–137.

Sattler, S., & Schunck, R. (2016). Associations between the big five personality traits and the non-medical use of prescription drugs for cognitive enhancement. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1971.

Sattler, S., & Wiegel, C. (2013). Cognitive test anxiety and cognitive enhancement: The influence of students’ worries on their use of performance-enhancing drugs. Substance Use & Misuse, 48, 220–232.

Sattler, S., Sauer, C., Mehlkop, G., & Graeff, P. (2013). The rationale for consuming cognitive enhancement drugs in university students and teachers. PLoS One, 8, e68821.

Schaufeli, W. B. (2017). Applying the job demands-resources model. Organizational Dynamics, 46, 120–132.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In G. F. Bauer & O. Hämmig (Eds.), Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health (pp. 43–68). Springer Netherlands.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Van Rhenen, W. (2009). How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30, 893–917.

Schleim, S., & Quednow, B. B. (2017). Debunking the ethical Neuroenhancement debate. In R. ter Meulen, A. Mohammed, & W. Hall (Eds.), Rethinking Cognitive Enhancement (pp. 164–176). Oxford University Press.

Schneider, T. R. (2004). The role of neuroticism on psychological and physiological stress responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 795–804.

Schneider, T. R., Rench, T. A., Lyons, J. B., & Riffle, R. R. (2012). The influence of neuroticism, extraversion and openness on stress responses. Stress and Health, 28, 102–110.

Schröder, H., Köhler, T., Knerr, P., Kühne, S., Moesgen, D., & Klein, M. (2015). Einfluss Psychischer Belastungen Am Arbeitsplatz Auf Das Neuroenhancement – Empirische Untersuchungen an Erwerbstätigen. Abschlussbericht. Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin.

Sherman, G. D., Lee, J. J., Cuddy, A. J. C., Renshon, J., Oveis, C., Gross, J. J., & Lerner, J. S. (2012). Leadership is associated with lower levels of stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109, 17903–17907.

Siegrist, J. (2002). Effort-Reward Imbalance at Work and Health. In Historical and Current Perspectives on Stress and Health (Vol. 2, pp. 261–291. Research in Occupational Stress and Well-Being 2). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Siegrist, J. (2016). Effort-reward imbalance model. In G. Fink (Ed.), Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior (pp. 81–86). Academic Press.

Slopen, N., Williams, D. R., Fitzmaurice, G. M., & Gilman, S. E. (2011). Sex, stressful life events, and adult onset depression and alcohol dependence: Are men and women equally vulnerable? Social Science & Medicine, 73, 615–622.

Smith, E. M., & Farah, M. J. (2011). Are prescription stimulants ‘smart pills’? The epidemiology and cognitive neuroscience of prescription stimulant use by Normal healthy individuals. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 717–741.

Stephenson, E., King, D. B., & DeLongis, A. (2016). Coping process. In G. Fink (Ed.), Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior (pp. 359–364). Academic Press.

Tadić, M., Bakker, A. B., & Oerlemans, W. G. M. (2015). Challenge versus hindrance job demands and well-being: A diary study on the moderating role of job resources. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(4), 702–725.

Tecco, J., Jacques, D., & Annemans, L. (2013). The cost of alcohol in the workplace in Belgium. Psychiatria Danubina, 25(Suppl 2), 118–123.

Terracciano, A., Löckenhoff, C. E., Crum, R. M., Joseph Bienvenu, O., & Costa, P. T. (2008). Five-factor model personality profiles of drug users. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 22–22.

Traweger, C., Kinzl, J. F., Traweger-Ravanelli, B., & Fiala, M. (2004). Psychosocial factors at the workplace—Do they affect substance use? Evidence from the Tyrolean workplace study. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 13, 399–403.

Turiano, N. A., Whiteman, S. D., Hampson, S. E., Roberts, B. W., & Mroczek, D. K. (2012). Personality and substance use in midlife: Conscientiousness as a moderator and the effects of trait change. Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 295–305.

Unrath, M., Zeeb, H., Letzel, S., Claus, M., & Escobar, P. (2012). Identification of possible risk factors for alcohol use disorders among general practitioners in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Swiss Medical Weekly, 142, w13664.

Upadyaya, K., Vartiainen, M., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2016). From job demands and resources to work engagement, burnout, life satisfaction, depressive symptoms, and occupational health. Burnout Research, 3, 101–108.

Vander Elst, T., Cavents, C., Daneels, K., Johannik, K., Baillien, E., Van den Broeck, A., & Godderis, L. (2016). Job demands–resources predicting burnout and work engagement among Belgian home health care nurses: A cross-sectional study. Nursing Outlook, 64, 542–556.

Vargo, E. J., & Petróczi, A. (2016). ‘It was me on a good day’: Exploring the smart drug use phenomenon in England. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 779.

Viswesvaran, C., Sanchez, J. I., & Fisher, J. (1999). The role of social support in the process of work stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 314–334.

Weyandt, L. L., White, T. L., Gudmundsdottir, B. G., Nitenson, A. Z., Rathkey, E. S., De Leon, K. A., & Bjorn, S. A. (2018). Neurocognitive, autonomic, and mood effects of Adderall: A pilot study of healthy college students. Pharmacy, 6, 58.

Wiegel, C., Sattler, S., Göritz, A. S., & Diewald, M. (2016). Work-related stress and cognitive enhancement among university teachers. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 29, 100–117.

Wiesner, M., Windle, M., & Freeman, A. (2005). Work stress, substance use, and depression among young adult workers: An examination of Main and moderator effect model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10, 83–96.

Winder-Rhodes, S. E., Chamberlain, S. R., Idris, M. I., Robbins, T. W., Sahakian, B. J., & Müller, U. (2010). Effects of Modafinil and prazosin on cognitive and physiological functions in healthy volunteers. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 24, 1649–1657.

Wolff, W., Brand, R., Baumgarten, F., Lösel, J., & Ziegler, M. (2014). Modeling students’ instrumental (Mis-) use of substances to enhance cognitive performance: Neuroenhancement in the light of job-demands-resources theory. BioPsychoSocial Medicine, 8, 12.

Zeike, S., Choi, K.-E., Lindert, L., & Pfaff, H. (2019). Managers’ well-being in the digital era: Is it associated with perceived choice overload and pressure from digitalization? An exploratory study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 1746.

Zhang, Z., & Snizek, W. E. (2003). Occupation, job characteristics, and the use of alcohol and other drugs. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 31, 395–412.

Zohny, H. (2015). The myth of cognitive enhancement drugs. Neuroethics, 8, 257–269.

Acknowledgments

Data gathering was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG; grant ID SFB882/01, B3, headed by Martin Diewald and Reinhard Schunck). Sebastian Sattler’s work was supported by the DFG [grant ID SA 2992/2-1]. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the policies of the funder. The authors did not receive any research support from public or private actors in the pharmaceutical sector. The authors do not have any competing financial interests and do not have any conflicts of interest. We thank Felix Lukowski for critical comments and Kelsey Hernandez for language editing.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Myriam Baum and Sebastian Sattler shared first authorship.

Appendix

Appendix

Appendix 1: Ethics Statement

Social science research in Germany that does not target research objectives regulated by certain laws (e.g., the German Medicine Act [Arzneimittelgesetz (AMG)], the Medical Devices Act [Medizinproduktegesetz (MGP)], the Stem Cell Research Act [Stammzellenforschungsgesetz (StFG)], or the Medical Association’s Professional Code of Conduct [Berufsordnung der Ärzte]), no ethics approval is required. This applies to the present study. Moreover, paragraph 28 of the Data Protection act of North Rhine Westphalia [Datenschutzgesetz Nordrhein-Westfalen (DSG NRW)] explains that personal data must be processed anonymously, and consent of participants is only required if the collected data are not used anonymously. The data of this study have been collected jointly by Bielefeld University and the Federal Institute for Employment Research (Institut für Arbeitsmarkt und Berufsforschung (IAB)). The study and all procedures have been approved by the security officer of the IAB and the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales (BAMS)). The procedures included cover letters that informed potential participants about the study subject, the voluntariness of their participation, their anonymity, and the confidentiality of their answers. This information was repeated during the first telephone contact. After being informed about these procedures, participation was understood as consent and agreement to participate.

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baum, M., Sattler, S. & Reimann, M. Towards an understanding of how stress and resources affect the nonmedical use of prescription drugs for performance enhancement among employees. Curr Psychol 42, 4784–4801 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01873-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01873-7