Abstract

In this study, we propose to examine two types of Parent Training (PT) under DDAA —behavioral and reflective types of PT. The central idea of our work is that the development of parenting educational skills cannot ignore the development of reflective and regulatory functions, which promote pre-mentalization, social cognition, and empathic skills. Because of the lack of studies on the efficacy of behavioral PT addressed to the parents of subjects with DDAA, this work took place. This study included 90 families whose children were diagnosed with the disorder of dysregulated anger and aggression (DDAA) according to criteria of CD 0–5 (2016). The sample included pre-school children aged between 2 and 3 years old (age range 2–3 years), who were equally divided into two groups based on the type of PT administered to the parents or caregivers. Our results indicate that the PT intervention, which is focused on the improvement of parental reflexive functions, helps in obtaining greater results even in the reduction of the externalizing behavioral symptoms. Additionally, results show that the intervention of PT with a behavioral matrix does not improve parental reflexive functions even if it guarantees a slight reduction of children’s behavioral problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

From birth, children have a genetic predisposition to receive regulation and emotional support from caregivers (especially the mother) through dyadic communication, which is the basis of emotional development. The regulation takes place, in fact, in the child's emission of behaviors through the regulation of his or her emotional states (Braet et al., 2014; Zeman et al., 2006), allowing him or her to respond adaptively and functionally to environmental requests. Fundamental to the development of emotional and behavioral self-regulation skills are the first years of life so that any difficulties in this stage of life might compromise the child's future socio-affective adaptation and future development of psychopathology. The Diagnostic Classification Manual 0-5 has identified a new diagnostic category called the Disorder of Dysregulated Anger and Aggression (DDAA hereafter), which is characterized by the pervasiveness of the emotional and behavioral dysregulation symptomatology in children from twenty-four months.

This disorder falls into the category of Mood Disorders, which also include early childhood depressive disorder and other moods in early childhood disorders. In particular, the DDAA-diagnosed children have outbreaks of anger, chronic irritability, and aggressive and destructive behavioral patterns. These symptoms might be present for at least three months (persistent) and involve a mismatch of multiple settings and the relationship with numerous people (pervasive) (Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and childhood – DC 0-5) (ZERO TO THREE, 2016). Emotional dysregulation may take the form of persistent irritability— an emotionality mainly tuned to anger, altered affectivity, outbursts of anger, and low tolerance to frustrations. Dysregulation of behavior involves not only non-adherence to rules, presence of aggressive, and destructive behaviors, but also coercive and controlling behaviors towards peers and adults. The deficit of regulation is considered as an alteration or a maturation delay of the processes of regulation and self-regulation. Take, for instance, speech disorders; it is not as a result of dysfunctional relationships with reference figures but rather the result of other diagnoses (Relationship Specific Disorder) (Mulrooney et al., 2019).

The main diagnostic difference between DDAA and other disorders such as ADHD and Autism is that, in the latter disorders, emotional and behavioral dysregulation may be present, but only as a symptom, and not the central or primary disorder. Moreover, DDAA differs from the Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) and the Conduct Disorder (CD) in that these disturbances are principally centered on behavior, while DDAA encompasses both emotional and behavioral dysregulation (Mulrooney et al., 2019). Emotional and behavioral regulation systems are influenced both by individual and environmental factors: among individual factors, temperament plays a crucial role, while among environmental factors, attachment styles and mentalization processes play a fundamental role (Gallegos et al., 2019; Rostad & Whitaker, 2016; Slagt et al., 2016; Wamser-Nanney & Campbell, 2020).

Among the environmental factors, mentalization processes are of considerable importance since they make it possible to predict the behavior of the other and to elicit the understanding of one's internal states by starting from the exploration of others’ internal states (Fonagy, 2002; Fonagy & Target, 1997).

Parental reflective functioning (PRF) is defined as the ability of parents to recognize their children's mental states, explain and make sense of their behavior in terms of thoughts, desires and expectations. This ability allows parents to reflect not only on their own internal mental experiences, but also on those of the child (Luyten, Mayes, et al., 2017; Luyten, Nijssens, et al., 2017; Mitjavila, 2013; Slade, 2005). Recent studies suggest that PRF helps parents cope with stressful parenting situations more effectively (Ammaniti & Gallese, 2014; Burkhart et al., 2017; Camoirano, 2017; Rutherford et al., 2015; Turner et al., 2008). Studies on parenting to date have sought to understand the mental processes that occur in parent-child relationships and their impact on both parenting and the child's socio-emotional adaptation (Rutherford et al., 2013). Several studies have shown that PRF is associated with feelings of parental competence (Nijssens et al., 2018; Rostad & Whitaker, 2016). Parental competence refers to the ability of parents to care for, educate and protect their children. They are therefore defined as parenting behaviors that involve an adequate response to the needs of their children in order to ensure the healthy development of children (Garaigordobil & Machimbarrena, 2017; Lopes & Dixe, 2012). In fact, parents can be expected to more likely respond appropriately and adaptively to their child's needs if they have the ability to reflect and understand the mental states behind their child's behavior (Ordway et al., 2015). In this regard, it has been suggested that parents with low PRF levels may perceive themselves as poorly competent parents (Nijssens et al., 2018; Slade, 2007). Indeed, parents with high PRF levels typically show a greater degree of involvement and communication with their child, practice more positive parenting styles and are generally more satisfied with their parenting role (Gordo et al., 2020; Rostad & Whitaker, 2016). A failure in the acquisition of mentalization can compromise not only the understanding of the other's mind, but also of one's own internal states, with the consequent experience of incomprehensible emotional experiences as well as difficulties in managing and controlling the impulsive responses that would dominate the most reflective. Repeated deficient interactions between child and caregiver can give rise to marked difficulties in the ability to independently tolerate and regulate emotions.

Studies also suggest that parents who tend not to be mental in relationships with their children show a greater tendency to confuse their children's anxiety-related signs (Rutherford et al., 2015). Similarly, difficulties in tolerating or making sense of their children's emotions impact children's socio-emotional adaptation because they lack the support of their primary caregivers in acquiring self-regulation skills (Camoirano, 2017; Gordo et al., 2020). In short, it appears that more reflective parents are likely to experience more positive interactions with their children, greater parental satisfaction and to be more engaged and communicative with their children (Rostad & Whitaker, 2016). This, in turn, promotes better mentalizing skills in children, greater social competence and fewer internalizing and externalizing problems (Allen et al., 2008; Benbassat & Priel, 2012; Camoirano, 2017; Fonagy et al., 2007; Luyten, Mayes, et al., 2017; Rosso et al., 2015; Scopesi et al., 2015; Sharp et al., 2006; Sharp & Fonagy, 2008).

Thus, although studies suggest that PRF may be related to parental competence, currently no studies have directly verified whether parenting competence is indeed a mediator in the relationship between parental (maternal) PRF and children's socio-emotional adaptation (Gordo et al., 2020). The central idea of the work is that the development of maternal educational skills cannot be separated from the development of reflexive and regulatory functions aimed at promoting pre-mentalization, social cognition and empathic skills. This work stems from the lack of studies on the effectiveness of a direct intervention on maternal Reflexive Functions to improve the emotional self-regulation abilities of their child (Pezzica & Bigozzi, 2015; Ruglioni et al., 2009); the work aims, in fact, at highlighting the benefits of training focused on strengthening maternal reflexive functions as compared to parents of children with DDAA.

Materials and Methods

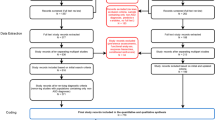

To address the objective of the study, we initially considered a sample of 100 Italian families. However, we excluded ten (Corp, IBM, 2019) families because they did not meet the specific characteristics that the study sought to examine. The total sample, therefore, included 90 families whose children were diagnosed with the disorder of dysregulated anger and aggression (DDAA) according to criteria of CD 0–5 (2016). The sample included pre-school children aged between 2 and 3 years old, who were equally divided into two groups based on the type of PT administered to the parents or caregivers (discussed in detail in the next paragraph). The first group included 45 children (33 male and 12 female) with a mean age of 2.5 (Mage = 2.5), while the second group comprised 45 children (33 male and 12 female) with a mean age of 3 (Mage = 3). The data were collected at the FINDS infant’s neuropsychiatry clinic, site in Caserta, by licensed psychologists (Fig. 1).

Instruments

The protocol used is composed of the following tests: Raven’s Matrices (Raven, 2008), Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and childhood – DC 0–5) (ZERO TO THREE, 2016), (PRFQ (Parental Reflective Function Questionnaire created by (Fonagy et al., 2016; Luyten, Mayes, et al., 2017), PSI/SF (Parenting Stress Index-Short Form authored by Abidin, 1990), and CBCL (Child Behaviour CheckList authored by Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000).

Raven’s Matrices (for Teens and Adults and SPM)

It is a measure of non-verbal intelligence throughout the span of intellectual development, from infancy to maturity, regardless of the cultural level, in subjects with cognitive deficits and mental retardation, with impaired understanding and verbal production. They are one of the most used tools for measuring “fluid” intelligence and require to analyze, build and integrate a series of concepts, directly, without resorting to subscales or summations of secondary factors. The SPM (Standard Progressive Matrices) test consists of 60 items divided into 5 series of 12 items each that measure the mental abilities of adolescents and adults.

DC: 0–5 (Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Childhood)

It is a developmentally based system that allows diagnosis in infants and toddlers, age groups in which traditional diagnostic manuals such as the DSM 5 and ICD 10 are not sensitive. This manual is divided into 5-axis: Clinical Disorders, Relational Context, Physical Health Condition and Considerations, Psychosocial Stressors, and Developmental Competence. Our study falls within the first axis, which contains criteria for the diagnosis of central disorders occurring in children aged 2 to 5 years. Although the diagnosis is not stable, the early identification of some difficulties guarantees early and preventive intervention.

PRFQ (Parental Reflective Function Questionnaire)

PRFQ is designed primarily for parents of children aged 0 to 5 years old. It is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 18 items, developed to provide a short multidimensional evaluation of the parental reflexive functions. It is divided into three subscales: PM (Pre-Mentalizing Models), CM (Certainty about Mental States), and IC (Interest and Curiosity in Mental States - Interests and Curiosities). These subscales evaluate parental curiosity about the child’s mental states, parental efforts to understand mental states, and how they are related to children’s behaviors.

PSI-SF (Parenting Stress Index-Short Form)

It is a self-assessment questionnaire that measures the level of stress in the parent-child system, consisting of two domains: child domain and parent domain. The child’s domain measures the sources of parental stress caused by child characteristics, while the Parent’s Domain assesses the sources of stress related to the parental role. The short form is made up of 36 items, organized into three subscales: Parental Distress (PD), Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction (PCDI), and Difficult Child (DC). The PD shows the level of stress experienced by the parent; the PCDI assesses the quality of the dyadic relationship, and the DC analyzes the difficulties of the child. Finally, Defensive response (DM) allows us to have information on parental defensive attitude and the global stress index.

Child Behavior CheckList (CBCL / 1½-5)

It is a self-administered questionnaire by parents for pre-school children that provides a profile of the child’s psychopathological behavior. It is composed of three syndromic scales: internalizing, externalizing, and total problem scales. The internalizing scales include Emotionally reactive, Anxious / Depressed, Somatic Complaints, and Withdrawn. Outsourcing problems evaluate Attention Problems and Aggressive Behavior. Besides, this scale also allows us to monitor problems related to the sleep-wake rhythm (Sleep Problems).

Procedures

The diagnosis was made following the diagnostic criteria of CD 0–5 through direct observation and administration to parents of CBCL 1½-5. The level of parental stress and the quality of reflective functions were investigated respectively by the administration of the PSI and PRFQ to the parents. PT began after the pre-tests for all participants and lasted six months. It took place four times a month, totaling 24 meetings. The total sample of 90 families, divided equally into two (Adkins et al., 2018) subgroups of 45 families, were subjected to a specific type of PT. PT is a psychological intervention aimed at improving parenting educational skills both in communicative-relational and behavioral management ways. Different theoretical approaches to PT can focus the attention mainly on one rather than on other issues and thus strengthen and bring different skills and abilities. In particular, Group 1 underwent a PT intervention aimed at restructuring parental reflective functions, which were inspired by pre-mentalization and emotional mirroring (Fonagy, 2002). On the other hand, Group 2 followed a PT of behavioral approach that was inspired by the Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA). It was aimed at enhancing skills and reducing the behavioral problems of children. At the end of the treatment, questionnaires were re-administered to the mothers in order to identify the differences between the children’s behavior (CBCL1½-5), parental stress and reflective functions (PSI / SF and PRFQ). Questionnaires scores were also used to detect the differences before and after the PT intervention in order to identify which of the two types of treatments yields better results.

Results

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 statistical survey software (2019). Significance was accepted at the 5% level (α < 0.05). Group averages were compared using the Student T Test, a statistical parameter test that can be used with two compared groups are independent from each other. Specifically, we used the T Test for paired samples, to make comparisons between groups, with two-tailed significance. In this study, we performed T TEST to compare scores within the individual groups that emerged from the administration of the tests, to see if differences emerged before and after PT. Specifically, for group 1, we compared the scores that emerged from the administration of the PSI/SF test before and after THE PT surgery, and significant results emerged at the Parental Distress (PD) subscale [t= −3,228; p < 0.05], the Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction (PCDI) [t = −1,618; p < 0.05] and THE DC (Difficult Child) [t = −2,975; p < 0.05] aftertreatment. The significance of these values indicate that the intervention helped parents to change children's dysfunctional behaviours and empower functional ones by actively making them agents of change; this also led to a reduction in parental stress. We compared the scores that emerged from the PRFQ questionnaire before and after PT surgery, and no significant results emerged. The results indicate that, despite PT intervention, reflective parenting functions and their ability to understand their child's mental state have not improved. Finally, we compared the CBCL scores before and after PT surgery and no significant results emerged. This value indicates that psychoeducation helps parents understand symptoms and functionally interpret them but does not significantly reduce children's outsourcing symptoms (Table 1 and Fig. 2). In group 2, we compared the scores registered in the PRFQ questionnaire before and after the PT intervention, and significant differences were found at the CM subscale [t = −31.32; p < 0.05], PM [t = −33.13; p < 0.05], and IC [t = −42.32; p < 0.05], after PT's intervention. The significance of these values indicates that PT intervention improves parental reflective functions and their ability to understand their child mental state, and this will also have a positive effect on the child's behaviour. We compared the scores that emerged from the administration of the PSI/SF test before and after PT surgery, and significant differences were found at the Parental Distress (PD) subscale [t = −26.42; p < 0.05], the Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction (PCDI) [ t = −22.83; p < 0.05], and DC (Difficult Child) [t = −35.56; p < 0.05], after treatment.The significance of these values indicate that PT intervention reduces the level of stress perceived by parents, also improving the quality of the caregiver-child relationship and the manifestation of behavioural issues. Significance, was also revealed by the DM value [t = −19.39; p < 0.05] after treatment, indicating an improvement in parental perception of self. Finally, we compared the CBCL scores before and after PT’s intervention, that showed a reduction in outsourcing symptoms, highlighted by the significance of the scores [t = −25.55; p < 0.05], (Table 2 and Fig. 3). A second comparison was carried out using the T TEST where the scores obtained by the two groups after treatment, was used to identify which of the two types of PT could both improve the reflective parenting functions and reduce the children’s behavioural problems with adjustment disorder. We compared the scores that emerged in the PRFQ questionnaire after the Parent Training intervention in the two groups and it was a significantly greater improvement in group 2 in the CM subscale [t = −34.73; p < 0.05], in the PM subscale [t = −34.79; p < 0.05], and in the IC subscale [t = −39.45; p < 0.05], after treatment. We then compared the scores that obtained via the administration of the PSI/SF test after PT intervention in the two groups, and a significantly greater improvement in group 1 at the Parental Distress (PD) subscale [t = −26.59; p < 0.05], to the Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interation (PCDI) [t = −30.50; p < 0.05], and to Difficult Child (DC) [t = −29.72; p < 0.05], after treatment. Finally, with the comparison of CBCL scores, it is shown a significant reduction in the largest outsourcing symptoms in children of families in the group 1 [t = −15.75; p < 0.05] (Table 3 and Fig. 4).

Discussions

In this study we wanted to investigate which type of PT offered greater improvements both for parental perception and for the dysfunctional behaviors of children. In group 2, our analyses showed an improvement in the caregiver’s ability to reflect on their own internal mental experiences and on those of the child (PRFQ - Parental Reflective Functioning; Ensink & Mayes, 2010; Sharp & Fonagy, 2008; Slade, 2005). Such outcome is evident from the improvement of the scores on the PRFQ test after the PT treatment focused on the improvement of these skills. In group 1, i.e. the behavioral matrix group, no improvements in parental reflexive functions emerged, evidenced by the non-significance of the scores on the PRFQ test after treatment. Parental Reflective Function refers to the caregiver’s ability to reflect on their own internal mental experiences and those of the child (mentalization). In accordance with existing literature, the present study shows that an improvement in parental reflexive functions improves parenting (Adkins et al., 2018; Camoirano, 2017; Kalland et al., 2016). Indeed, this ability is important for the development, in the child, of a theory of mind and for the regulation of emotions, as well as for the development of agency and for a secure attachment with the caregiver/s (Khalaila & Cohen, 2016; Slade, 2005). Regarding the scores detected by the PSI / SF administration to the mothers of the children, our analyses revealed a significant reduction in the PD (Parental Distress) and PCDI (Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction) subscales after administering the PT treatment in both groups, but to a greater extent in group 2. This data indicates that, with the improvement of parental reflexive functions, a reduction in the perception of stress by the latter is obtained and such outcome is accompanied by an improvement in the quality of the relationship with the child (Camoirano, 2017; Gordo et al., 2020; Rostad & Whitaker, 2016). Furthermore, a good caregiver-child relationship allows the development of mentalization (Fonagy, 2002; Frolli et al., 2019). Mentalization, that is the ability to understand one’s own thoughts, emotions, desires and those of others, implies a reflective component. In other words, if parents are unable to mentalize their child’s needs and provide him/her with adequate responses, and therefore in the absence of functional emotional mirroring, the child will be exposed to a prolonged experience of non-recognition. If the parents are unable to respond adequately, they deny the child a central psychological structure which is indispensable for building a stable sense of self (Fonagy & Target, 2001). The lack of mirroring generates a child unable to adapt in a functional way to the environment in which he/she lives because the parents do not identify her as an acting and thinking subject, thus unable to differentiate his/her own mind from that of others (Fonagy & Target, 2001). The acquisition of the reflexive function in parents is related to the development of the Theory of Mind (ToM) in the child, with positive implications in the relational field. In fact, it would allow the child to build adaptive and functional social relationships and interactions, with a good perception of the self. A child who does not have a ToM, on the other hand, will have difficulty in relating to others adequately because he/she will not be able to make sense of the behavior of others (Fonagy & Target, 2001; Frolli et al., 2019). The development of these skills favors a reduction in the problematic behaviors of children, resulting from the reduction of the DC (Difficult Child) index after the PT treatment in both groups, but to a greater extent in group 1. Finally, from the analysis of scores on the CBCL test, a reduction in externalizing symptoms emerged to a greater extent in group 2 after treatment, while in group 1 a reduction in externalizing symptoms emerged, but not significantly evident. These data indicate that the PT intervention focused on the improvement of parental reflexive functions allows to obtain greater results also for the reduction of externalizing behavioral symptoms (see Gershy & Gray, 2020), as evidenced by the analyses of group 1, while the behavioral matrix PT intervention does not improve parental reflexive functions but guarantees a reduction, albeit slight, of the problematic behaviors of children. The reflexive function of the parent plays a fundamental role in the process of adapting to reality: the caregiver, by offering a good responsiveness to the child, predisposes him/her to benefit from all those social interactive processes that facilitate the understanding of interpersonal dynamics, as well as the development of meta-cognitive processes that are fundamental for the organization of the Self. In addition, the parental reflexive functions guarantee the ability to tolerate frustration and help in reducing behaviors related to impulsivity and emotional dysregulation (Fonagy & Target, 2001; Fonagy et al., 1998). Therefore, a PT intervention to parents of children with emotional dysregulation problems can improve the behavioral aspects of the child only if provided through a training aimed to enhance parental reflexive functions (Camoirano, 2017; Gordo et al., 2020).

Conclusions

On the basis of these results, PT is confirmed as an intervention capable of improving the ways of managing children’s problem behaviors when used with behavioral techniques and seems to be more effective on emotional skills when contents aimed at emotional tuning are introduced. In fact, interventions are more effective when, alongside behavioral strategies, the parent is provided with strategies to enhance his/her own Parental Reflexive Function. Limitations of the present work are represented above all by the need to enlarge the sample numerically and by the lack of a longitudinal follow-up aimed at demonstrating that the effects of training on parental reflexive functions are long-lasting.

References

Abidin R.R. (1990), Parenting stress index/short form. Test Manual, University of Virginia.

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry.

Adkins, T., Luyten, P., & Fonagy, P. (2018). Development and preliminary evaluation of family minds: A mentalization-based psychoeducation program for foster parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(8), 2519–2532.

Allen, J., Fonagy, P., & Bateman, A. (2008). Mentalizing in clinical practice. American Psychiatric Press.

Ammaniti M. & Gallese V. (2014), La Nascita dell'Intersoggettività. Lo Sviluppo del Sé tra Psicodinamica e Neurobiologia. Raffaello Cortina Editore, pp. 285.

Benbassat, N., & Priel, B. (2012). Parenting and adolescent adjustment: The role of parental reflective function. Journal of Adolescence, 35(1), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.004.

Braet, C., Theuwis, L., Van Durme, K., Vandewalle, J., Vandevivere, E., Wante, L., et al. (2014). Regolazione delle emozioni nei bambini con problemi emotivi. Terapia cognitiva e ricerca, 38(5), 493–504.

Burkhart, M. L., Borelli, J. L., Rasmussen, H. F., Brody, R., & Sbarra, D. A. (2017). Parental mentalizing as an indirect link between attachment anxiety and parenting satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 31(2), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000270.

Camoirano, A. (2017). Mentalizing makes parenting work: A review about parental reflective functioning and clinical interventions to improve it. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00014.

Corp, IBM (2019). Statistiche IBM SPSS per Windows, versione 26.0. IBM Corp.

Ensink, K., & Mayes, L. C. (2010). The development of mentalisation in children from a theory of mind perspective. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 30(4), 301–337.

Fonagy P. (2002), Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the self. New York: Other press; xiii, 577 p. p.

Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., & Target, M. (2007). The parent-infant dyad and the construction of the subjective self. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(3–4), 288–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01727.x.

Fonagy P., Luyten P., Moulton-Perkins A., Lee Y.W., Warren F., Howard S. et al. (2016), Sviluppo e validazione di una misura self-report di mentalizzazione: il Questionario sul funzionamento riflessivo. PLOS ONE. 2016; 11 (7): e0158678. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158678.

Fonagy, P., Steel, M., Steel, H., & Target, M. (1998). Reflective-functioning manual version 5. University College London.

Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (1997). Attachment and reflective function: Their role in self-organization. Development and Psychopathology, 9(4), 679–700.

Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (2001). Attaccamento e funzione riflessiva: il loro ruolo nell’organizzazione del Sé. In P. Fonagy & M. Target (Eds.), Attaccamento e funzione riflessiva (pp. 101–133). Raffaello Cortina.

Frolli, A., La Penna, I., Cavallaro, A., & Ricci, M. C. (2019). Theory of mind: Autism and typical development. Acad. J. Ped. Neonatol, 8, 555799.

Gallegos, M. I., Jacobvitz, D. B., Sasaki, T., & Hazen, N. L. (2019). Parents’ perceptions of their spouses’ parenting and infant temperament as predictors of parenting and coparenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 33(5), 542–553.

Garaigordobil, M., & Machimbarrena, J. M. (2017). Stress, competence, and parental educational styles in victims and aggressors of bullying and cyberbullying [Estrés, competencia y prácticas educativas parentales en víctimas y agresores de bullying y cyberbullying]. Psicothema, 29(3), 335–340. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.258.

Gershy, N., & Gray, S. A. (2020). Parental emotion regulation and mentalization in families of children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(14), 2084–2099.

Gordo, L., Martinez-Pampliega, A., Elejalde, L. I., & Luyten, P. (2020). Do parental reflective functioning and parental competence affect the socioemotional adjustment of children? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(12), 3621–3631.

Kalland, M., Fagerlund, Å., von Koskull, M., & Pajulo, M. (2016). Families first: The development of a new mentalization-based group intervention for first-time parents to promote child development and family health. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 17(1), 3–17.

Khalaila, R., & Cohen, M. (2016). Emotional suppression, caregiving burden, mastery, coping strategies and mental health in spousal caregivers. Aging & Mental Health, 20(9), 908–917.

Lopes, M., & Dixe, M. (2012). Positive parenting by parents of children up to three years of age: Development and validation of measurement scales. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 20(4), 787–795. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692012000400020.

Luyten, P., Mayes, L. C., Nijssens, L., & Fonagy, P. (2017). The parental reflective functioning questionnaire: Development and preliminary validation. PLoS One, 12(5), e0176218. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176218.

Luyten, P., Nijssens, L., Fonagy, P., & Mayes, L. C. (2017). Parental reflective functioning: Theory, research, and clinical applications. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 70(1), 174–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/00797308.2016.1277901.

Mitjavila, M. (2013). Investigación y aportaciones de Peter Fonagy: una revisión desde el 2002 al 2012. Temas de psicoanálisis, 3.

Mulrooney, K., Egger, H., Wagner, S., & Knickerbocker, L. (2019). Diagnosis in young children: The use of the DC:0-5™ diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders in infancy and early childhood. Clinical Guide to Psychiatric Assessment of Infants and Young Children, pp., 253–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-10635-5_8.

Nijssens, L., Bleys, D., Casalin, S., Vliegen, N., & Luyten, P. (2018). Parental attachment dimensions and parenting stress: The mediating role of parental reflective functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(6), 2025–2036. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1029-0.

Ordway, M. R., Webb, D., Sadler, L. S., & Slade, A. (2015). Parental reflective functioning: An approach to enhancing parent–child relationships in pediatric primary care. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 29(4), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.12.002.

Pezzica, S., & Bigozzi, L. (2015). Un PTcognitivo comportamentale e mentalizzante per bambini con ADHD. Psicologia Clinica dello Sviluppo, 19(2), 271–296.

Raven, J. (2008). The Raven progressive matrices tests: Their theoretical basis and measurement model. Uses and abuses of Intelligence. Studies advancing Spearman and Raven’s quest for non-arbitrary metrics, 17–68.

Rosso, A. M., Viterbori, P., & Scopesi, A. M. (2015). Are maternal reflective functioning and attachment security associated with preadolescent mentalization? Frontiers in Psychology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01134.

Rostad, W. L., & Whitaker, D. J. (2016). The association between reflective functioning and parent–child relationship quality. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(7), 2164–2177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0388-7.

Ruglioni, L., Muratori, P., Polidori, L., Milone, A., Manfredi, A., & Lambruschi, F. (2009). Il trattamento multi-modale dei disturbi da comportamento dirompente in bambini di età scolare: presentazione di una esperienza. Cognitivismo Clinico, 6(2), 196–210.

Rutherford, H. J., Booth, C. R., Luyten, P., Bridgett, D. J., & Mayes, L. C. (2015). Investigating the association between parental reflective functioning and distress tolerance in motherhood. Infant Behavior and Development, 40, 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2015.04.005.

Rutherford, H. J., Goldberg, B., Luyten, P., Bridgett, D. J., & Mayes, L. C. (2013). Parental reflective functioning is associated with tolerance of infant distress but not general distress: Evidence for a specific relationship using a simulated baby paradigm. Infant Behavior and Development, 36(4), 635–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2013.06.008.

Scopesi, A. M., Rosso, A. M., Viterbori, P., & Panchieri, E. (2015). Mentalizing abilities in preadolescents’ and their mothers’ autobiographical narratives. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 35(4), 467–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431614535091.

Sharp, C., & Fonagy, P. (2008). The parent's capacity to treat the child as a psychological agent: Constructs, measures and implications for developmental psychopathology. Social Development, 17(3), 737–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00457.x.

Sharp, C., Fonagy, P., & Goodyer, I. M. (2006). Imagining your child’s mind: Psychosocial adjustment and mothers’ ability to predict their children’s attributional response styles. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 24(1), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151005X82569.

Slade, A. (2005). Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attachment & Human Development, 7(3), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500245906.

Slade, A. (2007). Reflective parenting programs: Theory and development. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 26(4), 640–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351690701310698.

Slagt, M., Dubas, J. S., Deković, M., & van Aken, M. A. (2016). Differences in sensitivity to parenting depending on child temperament: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 142(10), 1068–1110.

Turner, J. M., Wittkowski, A., & Hare, D. J. (2008). The relationship of maternal mentalization and executive functioning to maternal recognition of infant cues and bonding. British Journal of Psychology, 99(4), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712608X289971.

Wamser-Nanney, R., & Campbell, C. L. (2020). Predictors of parenting attitudes in an at-risk sample: Results from the LONGSCAN study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 99, 104282.

Zeman, J., Cassano, M., Perry-Parrish, C. E., & Stegall, S. (2006). Regolazione delle emozioni nei bambini e negli adolescenti. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 27(2), 155–168.

ZERO TO THREE. (2016). DC:0–5™: Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood. Author.

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files). The other dataset not available in the article are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Maria Carla Ricci and Antonella Cavallaro.

The first draft of the manuscript was written by Antonella Cavallaro and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conceptualization: Alessandro Frolli, Maria Carla Ricci and Antonella Cavallaro.

Formal analysis and investigation: Antonella Cavallaro and Maria Carla Ricci.

Writing - review and editing: Cavallaro Antonella, Maria Carla Ricci and Stephen Oduro.

Resources: Antonia Bosco and Lombardi Agnese.

Supervision: Alessandro Frolli, Maria Carla Ricci, Cavallaro Antonella, Di Carmine Francesca and Stephen Oduro.

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors guarantee that questions relating to the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work, even those in which an author was not personally involved, have been properly investigated, resolved and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study, in the case of children under 16 written informed consent was obtained from the parents.

Consent for Publication

A written consent to publish was given to author from parents of each partecipant.

Code Availability

(not applicable)

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Frolli, A., Cavallaro, A., Oduro, S. et al. DDAA and Maternal Reflective Functions. Curr Psychol 42, 7788–7796 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01818-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01818-0