Abstract

There is still a scarcity of studies showing the relative contribution of different personality characteristics differentiating various behavioral addictions within an integrated model. In comparison to other addictions, fairly little is known about the role of specific personality traits in compulsive shopping. In addition, few studies have investigated the unique contribution of shopping addiction in terms of explaining different facets of well-being above and beyond personality characteristics previously shown to be related to psychosocial functioning. The present study shows validation of the Bergen Shopping Addiction Scale (BSAS) and a tentative integrated model of potential shopping addiction personality risk factors. BSAS was administered to 1156 Polish students. In addition, demographic variables, and personality traits (Big Five), self-esteem, self-efficacy, perceived narcissism, loneliness, social anxiety, and well-being indicators were measured. BSAS had acceptable fit with the data and demonstrated good reliability. The investigated model showed that shopping addiction was related to higher extraversion, perceived narcissism, and social anxiety, and lower agreeableness and general self-efficacy. Woman and older participants scored higher on BSAS. Shopping addiction was further related to all facets of impaired well-being and explained worse general health, and decreased sleep quality above and beyond other variables in the model. The results support the notion that shopping addiction may have specific personality risk factors with low agreeableness as an outstanding characteristic. This has implications for the development of early prevention and intervention programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Compulsive buying has been a subject of research for a couple of decades now, since shopping no longer serves only a practical purpose, but is also considered a leisure activity, a form of entertainment or a reward (Maraz et al., 2016; Mestre-Bach et al., 2017). Despite buying being an inherent part of everyday routine, in some cases, when spending is unplanned and sudden with a high frequency of such behavior, it may have severe consequences, usually on a psychological and financial level (da Silva, 2015; Lejoyeux & Weinstein, 2010). The previous studies showed that shopping addiction is a feasible candidate as a potential behavioral addiction (Mestre-Bach et al., 2017; Müller et al., 2019) as it phenomenologically presents itself as addiction (Clark & Calleja, 2008; Piquet-Pessôa et al., 2014), it is temporarily stable in a significant number of cases (Black, 2007; Schlosser et al., 1994), and it is related to adverse effects in the form of significant harm and distress (Faber & O’Guinn, 1992; Otero-López & Villardefrancos, 2014). Also, case studies substantiate assuming addiction framework in relation to compulsive buying behavior (Glatt & Cook, 1987; Yeh et al., 2008). However, similarly to some other problematic behaviors such as exercise (Berczik et al., 2012), work (Griffiths et al., 2018) and study (Atroszko, 2015; Atroszko, Andreassen, et al., 2015), social networking (Kuss & Griffiths, 2011) or mobile phone use (Billieux et al., 2015) more research is needed to establish their addictive status.

The aim of this study was to investigate the validity and reliability of recently developed the Bergen Shopping Addiction Scale (BSAS; Andreassen et al., 2015), a measure of compulsive buying behavior grounded in addiction theory and research, and the relationship of shopping addiction with wide range of crucial personality traits as potential risk factors for developing this problematic behavior, as well as its contribution to the well-being above and beyond personality characteristics known to be closely related to psychosocial functioning. The study was conducted among Polish undergraduate students. Research among young populations is congruent with recent systemic efforts to identify vulnerable individuals at risk of problematic compulsive and addictive behaviors for early intervention (see for example, Fineberg et al., 2018).

The Bergen Shopping Addiction Scale (BSAS; Andreassen et al., 2015) is based on common addiction components (Brown, 1993; Griffiths, 2005) and has shown good validity and reliability in a previous study (Andreassen et al., 2015). The scale can be used both to traditional shopping as well as online shopping which contributes to its universality and convenience of application. The scale asks about the frequency of experiencing seven symptoms, including salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, relapse, and problems such as impaired well-being. In recent years, addiction component model has proved to be very useful in facilitating empirical research of the newly conceptualized behavioral addictions (Kuss & Griffiths, 2011) as well as advancing those with a relatively longer history of research (Griffiths et al., 2018). Still, conceptual and methodological rigor has been emphasized when applying this model in practice to prevent overpathologizing everyday behaviors (Atroszko, 2018, 2019; Kardefelt-Winther et al., 2017).

Definition

Differences in the motivation behind making the purchase in normal and pathological shopping are crucial for defining compulsive buying. In the case of shopping dependent individuals, the value of acquired goods is secondary, as the underlying cause for spending is to reduce tension and manage negative emotions (Black, 2007; Lejoyeux & Weinstein, 2010; O’Guinn & Faber, 1989). Possible misconceptions also concern impulsive and compulsive buying. Impulsive purchases happen to each consumer occasionally and should not always be defined as dysfunctional. Contrary to compulsive spending, impulsive behavior does not result in reducing the tension and does not aid directly in managing emotions; nevertheless, both phenomena are somehow linked (Faber, 2010). Suggested diagnostic criteria for compulsive shopping include being preoccupied with buying, intrusive impulses to buy, spending more than can be afforded, often on items not needed and useless, with a result of distress and interference in social, financial, occupational functioning, with episodes occurring not only during hypomania or mania (McElroy et al., 1994). In line with this, Andreassen (2014, p. 198) described compulsive shopping as „being overly concerned about shopping, driven by an uncontrollable shopping motivation, and investing so much time and effort into shopping that it impairs other important life areas.”

However, due to lack of sufficient data, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM 5) only recognizes gambling as a behavioral addiction (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). According to this classification, shopping falls into the residual category of „Disorder of Impulse Control Not Otherwise Specified”, whereas it is still a subject of debate whether maladaptive spending is a matter of impulse-control, obsessive-compulsive or addiction-related behavior (Müller et al., 2015; Müller et al., 2019; Piquet-Pessôa et al., 2014; Potenza, 2014). Nevertheless, it has been argued that categorizing some cases of problematic shopping as an addiction fits to the existing data related to shopping itself (Andreassen et al., 2015; Mestre-Bach et al., 2017; Müller et al., 2019), as well as it is consistent with studies on the nature of addictive behaviors (Konkolÿ Thege, 2017; Sussman et al., 2017; Tunney & James, 2017). Compulsive buying also seems consistent with core addiction components which include salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, conflict, and relapse and problems (Brown, 1993; Griffiths, 2005).

Prevalence

The estimates of prevalence of compulsive buying vary substantially between the samples, with results suggesting that between 2 and 8% of individuals could be affected (Black, 2007; Koran et al., 2006; Maraz et al., 2016), although in some research numbers reach up to 16% (Magee, 1994). Detailed information on the prevalence rates in particular countries can be found in a meta-analysis (Maraz et al., 2016). This high variability of prevalence estimates is a common problem in behavioral addictions, such as internet gaming disorder (from less than 2% to 8–10%; Zajac et al., 2017) social network sites addiction (1.6 to 34%; Griffiths et al., 2014), exercise addiction (2.5 to 77%; Berczik et al., 2012; Hausenblas & Symons Downs, 2002) or work/study addiction (7.3–25%; Griffiths et al., 2018). While maintaining consistent definition and measurement improves the precision of those estimates (Berczik et al., 2012; Zajac et al., 2017), even studies based on the same cut-off score for particular problematic behavior show high variability depending on the samples (6.6–20.6%; Lichtenstein et al., 2019; Orosz et al., 2016). It clearly contrasts with reasonably good reliability of estimates for officially recognized pathological gambling (around 1%; Sussman et al., 2010). As in the case of other behavioral addictions, problems with conceptualizing problematic shopping, lack of consensus on the diagnostic criteria and diversity of existing measures and studied samples are most probably reasons for such disparities (Maraz et al., 2016; Piquet-Pessôa et al., 2014). This indicates a pending need for more consistent and systematic studies following more rigorous conceptual and methodological standards, especially the use of valid and reliable measures grounded in addiction theory such as BSAS.

Most of the research suggests that females are the predominant group among individuals with compulsive buying, sometimes reaching between 80%, up to 95% of all the subjects (Black, 2007; Christenson et al., 1994; Dittmar, 2005; Lejoyeux & Weinstein, 2010). In spite of its more hedonistic rather than nurturant nature, it is a socially acceptable way of coping, especially for women, which would at least partially explain why they more often struggle with a shopping addiction, as women usually favor socially sanctioned forms of indulgence (Fattore et al., 2014). However, Koran et al. (2006) found no effect of gender in studies on compulsive buying.

The age of onset of this disorder is estimated at the early twenties (Koran et al., 2006; Maraz et al., 2016), following the start of financial independence. However, other researchers suggest that problems with shopping start later, at the mean age of 30 years (McElroy et al., 1994). Usually compulsive buying is related to younger age; however, in many prevalence studies, the mean age of participants is between 30 and 40 years (Koran et al., 2006; Maraz et al., 2015; Mueller, Mitchell, et al., 2010). Other studies suggest that earlier onset of the disorder is associated with more severe symptoms of compulsive buying (Granero et al., 2016). For this rationale, the sample in the present study comprises of university students. It will help identify potential risk factors at the very early stage. Due to the demographic characteristic of the participants, we assume that relatively older age will be positively related to shopping addiction in the present sample, as it increases the likelihood of financial independence from a parental household and more advanced stage of addiction.

Previous studies suggest that income has little effect on compulsive spending (Achtziger et al., 2015), moderating only the type of stores chosen, rather than the preoccupation with thoughts of shopping or intensity of behavior. Nevertheless, the problem with compulsive buying occurs mostly in developed countries with the market-based economy, availability of various goods, disposable income, and significant leisure time (Black, 2007).

Shopping Addiction and Personality

The Big Five personality traits may contribute either as a risk or protective factors for addictive tendencies (Mccormick et al., 1998; Mikołajczak-Degrauwe et al., 2012; Zilberman et al., 2018). Neuroticism, as well as extraversion, has been positively linked to compulsive buying (Andreassen et al., 2013; Balabanis, 2002; Mikołajczak-Degrauwe et al., 2012). Conscientiousness, on the other hand, showed negative relationship with compulsive buying (Andreassen et al., 2013) and might be a protective factor for shopping addiction, as those who score low on this trait are more likely to be less structured, irresponsible and self-indulgent (Andreassen et al., 2015; Mowen & Spears, 1999). Moreover, it has also been shown that compulsive buying is strongly associated with poor self-regulation and self-control, along with an inability to efficiently cope with negative emotions (Billieux et al., 2008; Claes et al., 2010; Claes & Müller, 2017; Faber & Vohs, 2004).

Relationship between agreeableness and compulsive shopping appears to be more complex, as some argue that it is a predictor of the addiction (Mikołajczak-Degrauwe et al., 2012; Mowen & Spears, 1999) while others list it as a protective factor (Andreassen et al., 2013; Andreassen et al., 2015; Balabanis, 2002), depending on whether agreeableness is examined as being prone to marketing techniques or as avoidance of conflicts and instability, typically related with addictions. However, high levels of hostility and interpersonal sensitivity among people with compulsive buying (Mueller, Claes, et al., 2010) support the notion that shopping addiction is related to lower agreeableness. Furthermore, lower scores on cooperativeness were also distinctive for the highly dysfunctional cluster of individuals with shopping addiction (Granero et al., 2016).

Shopping Addiction, Well-Being, Self-Concept and Social Functioning

One of the essential components of addiction is the negative relationship that it has with the psychosocial functioning of the individual and people close to them (Grant et al., 2010; Griffiths, 2005). Compulsive buying has been linked to lower subjective well-being (Dittmar, 2005; Otero-López & Villardefrancos, 2014; Zhang et al., 2017), as well as feelings of guilt, alienation, loneliness and marital problems (Christenson et al., 1994; O’Guinn & Faber, 1989). Another major issue arising from compulsive buying include increasing debts and financial problems that affect social and occupational functioning (Christenson et al., 1994; Roberts & Jones, 2001).

Furthermore, individuals who involve in excessive spending have also reported higher levels of stress and poorer physical health (Harvanko et al., 2013). In terms of mental health, compulsive buying often co-occurs with other disorders, such as depression, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, impulse control disorder or eating disorders (Black et al., 1998; Lejoyeux & Weinstein, 2010; McElroy et al., 1991; Müller et al., 2015). Moreover, people with compulsive buying are more likely to develop problems with substance abuse (Black et al., 1998; Müller et al., 2019). The comorbidity with other disorders and the impaired psychosocial functioning support the notion that addictions are often coping mechanisms with other underlying problems, such as elevated levels of stress, dissatisfaction with close relationships, or poor health (Atroszko, 2018, 2019; Griffiths, 2017; Jacobs, 1986; Konkolÿ Thege, 2017; Marmet et al., 2018; Sussman et al., 2011, 2017).

Low self-esteem has also been associated with compulsive buying in previous research, along with materialistic values (Davenport et al., 2012; Dittmar, 2005; Hanley & Wilhelm, 1992; O’Guinn & Faber, 1989; Yurchisin & Johnson, 2004), supporting the notion that shopping is a mean to improve self-esteem by enhancing the perceived social status (Dittmar, 2005; Hanley & Wilhelm, 1992). This assumption is corroborated by the studies which found a positive connection between problematic spending and narcissism (Krueger, 1988; Rose, 2007). Buying certain products may represent wealth and traits associated with it, such as competency and intelligence. For narcissistic individuals, excessive spending may be important as a self-presentation strategy that suggests their high social status. Since it does not relieve the insecurities underlying narcissism, shopping may over time become problematic.

Self-efficacy is an evaluation about the individual’s capability to manage different situations and execute behaviors to achieve desired outcomes (Bandura, 1997). Its low levels are consistently related to a wide range of addictive behaviors (Atroszko et al., 2018; Iskender & Akin, 2010; Jeong & Kim, 2011; Marlatt et al., 1995). Fairly little is known about associations between shopping addiction and self-efficacy; however, some research has found it to be negatively associated with compulsive buying behavior (Jiang & Shi, 2016). Maladaptive coping might be related to the lack of belief in one’s capacity to effectively solve problems, hence we suggest that shopping addiction will be negatively associated with self-efficacy.

Previous research in the field of behavioral addictions has shown that individuals excessively engaging in certain activities usually struggle with problematic social life and often experience lack of social support and the feeling of loneliness (Bozoglan et al., 2013; Ste-Marie et al., 2002; Trevorrow & Moore, 1998). In terms of social functioning of people with compulsive buying, fairly little is known in comparison to other addictions. On the basis of previous studies (O’Guinn & Faber, 1989; Schlosser et al., 1994; Wang & Xiao, 2009) we may expect that shopping addiction is also related to loneliness. Compulsive buying may be used as a way to escape from the feeling of alienation, but it can also contribute to the escalation of interpersonal conflicts due to a continual intensification of the behavior.

Previous studies both on substance use and behavioral addictions linked these problematic behaviors to social anxiety (Atroszko, 2015; Atroszko et al., 2018; Buckner & Schmidt, 2008; Caplan, 2007; Dobrean & Păsărelu, 2016; Lawendowski et al., 2019), which suggests that it may also play a role in shopping addiction. Pathological buying may be to some extent a means to deal with social anxiety. However, the association between these two constructs may be complex. Social anxiety may limit the capability to establish satisfying relationships among individuals with shopping addiction. The inability to build strong, trustworthy connections preclude people from seeking support from close ones when facing problems. It is also possible that people with compulsive buying attempt to make themselves more likable through the acquisition of material goods that represent affluence and success. Shopping is then an indirect way to improve self-presentation, and consequently relieve anxiety in social contacts. Therefore, we can expect that social anxiety will be positively related to shopping addiction.

Tentative Model of Shopping Addiction Risk Factors

Understanding addiction as an issue of emotion regulation and stress coping (Atroszko, 2019; Jacobs, 1986; Marmet et al., 2018; Shaffer et al., 2004; Sinha, 2008; Sussman et al., 2017), indicates that on the basis of previous research we can presume that shopping addiction is an ineffective mechanism of mood regulation that is related to emotional instability, extraversion, low conscientiousness, low self-esteem, narcissism, low self-efficacy, as well as loneliness and social anxiety. While all addictions seem to share the proclivity of affected individuals to experience negative emotions (neuroticism), and reduced self-efficacy and self-esteem, there seem to be idiosyncratic individual risk factors. For example, work and study addiction are associated with high levels of conscientiousness (Andreassen et al., 2013; Atroszko, 2015; Griffiths et al., 2018), which makes them different than other addictions. Facebook addiction seems to be driven by a combination of high needs for social approval and appreciation combined with helplessness and social anxiety (Andreassen et al., 2013; Atroszko et al., 2018). Previous studies suggest that shopping addiction could be related to higher impulsiveness and disagreeableness combined with a need for high social status (Andreassen et al., 2015; Billieux et al., 2008; Roberts & Jones, 2001).

On the basis of previous research and theoretical frameworks it can be hypothesized that that (i) the Polish adaptation of Bergen Shopping Addiction Scale has satisfactory factorial validity and reliability (H1); (ii) female gender and older age have positive relationship with shopping addiction (H2), (iii) neuroticism and extraversion have positive relationship with shopping addiction, while conscientiousness, and agreeableness are negatively related to shopping addiction (H3); (iv) shopping addiction is negatively related to subjective well-being (H4); (v) self-esteem and self-efficacy are negatively related to shopping addiction, whereas evaluating oneself as more narcissistic is positively related to shopping addiction (H5); (vi) loneliness and social anxiety are positively related to shopping addiction (H6).

Methods

Sample

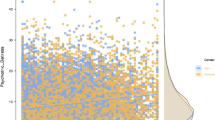

The sample consisted of 1156 students: 601 females (52.0%), 545 males (47.2%) and 10 persons (0.9%) who did not report gender, with a mean age of M = 20.33 years (SD = 1.68). The participants attended different courses, modes, years of study, and faculties from three different universities from [Gdańsk: University of Gdańsk, Gdańsk Technological University and Gdańsk University of Sport and Recreation]. Missing data were imputed when data were missing at random, and only a very small portion of data were missing (less than 2% overall). Expectation–maximization (EM) algorithm within SPSS 25.0, which provides unbiased estimates of parameters (Enders, 2001; Scheffer, 2002), was used to perform imputation.

Instruments

Bergen Shopping Addiction Scale (BSAS; Andreassen et al., 2015) includes 7 items, one for each of seven addiction criteria (salience, mood modification, conflict, tolerance, withdrawal, relapse, and problems), based on core addiction components (Brown, 1993; Griffiths, 2005). The questions focus on symptoms experienced during the past 12 months. The responses are provided on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from completely disagree (1) to completely agree (5). Higher scores indicate greater shopping addiction. The BSAS was translated in a multistep, standardized procedure to assure linguistic equivalence of the Polish version. In the first step, the BSAS was translated from English to Polish by two translators (one lay person and one psychologist). Both versions were then compared to each other during the discussion session with the translators, a psychometrician, and psychology students. One polish version was prepared and then back translated by two other independent translators (one lay person and one psychologist). In the course of next discussion session, back translations, the original version and the initial Polish version were compared to establish the final version. In the present sample, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient was 0.87 and the McDonald’s omega reliability coefficient was 0.94.

The Polish version of the Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI; Gosling et al., 2003) was used to measure the Big Five personality traits. Using the 7-point Likert scale, which ranges from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7), the inventory measures Big Five qualities with two items for each factor, one for its positive and the other for its negative extremity. It has shown good validity and reliability in previous research (Atroszko, 2015; Atroszko et al., 2016a, 2016b). In the present sample, the Spearman-Brown reliability coefficient was .68 for Extraversion, .29 for Agreeableness, .65 for Conscientiousness, .56 for Emotional stability and .28 for Openness to experience. These were reasonably similar to the ones obtained in the original version of the scale, which were .68, .40, .50, .73, and .45 respectively. As the authors of the scale argue, TIPI demonstrates good validity and biased estimates of reliability using internal consistency measures should be expected due to a very small number of items. Therefore, less biased measures of reliability should be used, such as the test-retest reliability, which for the original scale yielded acceptable correlations between two measurements with a 6-week interval between them, varying from .62 for Openness to .77 for Extroversion.

Global self-esteem was measured with a single-item scale developed on the basis of an item from WHQOOL-BREF scale (Skevington et al., 2004) with a 9-point response scale, from very dissatisfied to very satisfied. The scale has shown good validity and reliability in previous research (Atroszko et al., 2017; Atroszko et al., 2018). In the previous study, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for test-retest reliability with a 3-week interval between measurements was .79.

Perceived narcissism was measured with the Single Item Narcissism Scale (SINS; Konrath et al., 2014). The participants were presented with the following statement: “I am a narcissist (Note: The word ‘narcissist’ means egotistical, self-focused, and vain)” with response range from No (1) to Yes (9). In this study, response format has been extended to a 9-point scale. The item has shown good validity and reliability in previous research (Atroszko et al., 2018; Konrath et al., 2014). SINS measures more undesirable elements of narcissism therefore it is not consistently related to self-esteem.

Self-efficacy was measured by two items based on the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES; Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995). The measure includes the following items: “I can usually handle whatever comes my way” and “I can solve most problems if I invest the necessary effort.” Respondents provided answers on a 9-point Likert scale, from no (1) to yes (9). The two items have the highest content validity, and its criterion validity is supported by previous studies (Atroszko et al., 2018), congruent with previous results with the full version of the scale (Schwarzer et al., 2012). In the present sample, the Spearman-Brown reliability coefficient was of .81.

Social anxiety was measured with a shortened Polish version (Dąbkowska, 2008) of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS; Liebowitz, 1987). It consists of nine items from the original scale concerning the component of fear experienced in social situations. The responses are provided on a 4-point scale ranging from none (0) to severe (3). Data supports the good validity of this version of the scale (Atroszko et al., 2018). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of social anxiety in this sample was .83 and the McDonald’s omega reliability coefficient was 0.87.

Loneliness was measured by Three-Item Loneliness Scale (TILS: Hughes et al., 2004). The response options for each item were hardly ever (1) some of the time (2) or often (3). The scale has shown good validity and reliability in previous research (Atroszko, 2015; Atroszko et al., 2018). In the present sample, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient was .79 and the McDonald’s omega reliability coefficient was 0.88.

Perceived stress was measured with Perceived Stress Scale-4 (PSS-4; Cohen et al., 1983). The PSS-4 consists of 4 items, 5-point Likert response format scale, rated from Never (0) to Very often (4). The Polish version of the scale has shown good validity and reliability in previous research (Atroszko, 2015; Atroszko et al., 2018). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient in this sample was .69 and the McDonald’s omega reliability coefficient was 0.75.

General health, sleep quality, and general quality of life were measured with a 9-point response scale, from very dissatisfied to very satisfied [General health, sleep quality]; from very poor to very good [general quality of life], based on the items from WHQOL-BREF scale (Skevington et al., 2004). The scales have shown good validity and reliability in previous research (Atroszko, Andreassen, et al., 2015; Atroszko, Bagińska, et al., 2015). In previous study intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for test-retest reliability with a 3-week interval between measurements were satisfying, .86 for general quality of life, .72 for general health and .81 for sleep quality (Atroszko, Bagińska, et al., 2015).

Procedure

Data collection was based on convenience sampling. Students were invited to participate anonymously in the study during lectures or classes. The estimated response rate was above 95%. No monetary or other material rewards were offered. Data were gathered in 2016.

Statistical Analyses

A confirmatory factor analysis was performed using Mplus 6.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010). Due to the strictly ordinal character of the response scale, the CFA models were tested using the weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator. Missing data were handled with the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm. Following measures were used to evaluate the fit of the model: χ2 divided by degrees of freedom (χ2/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Cut-off scores for those indexes for acceptable fit are: χ2/df ≤ 3, CFI ≥ 0.95, TLI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤0.06 to 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Schreiber et al., 2006).

For short and unidimensional scales, McDonald’s omega reliability coefficients were calculated in Mplus 6.11 because they provide more accurate estimation of instruments’ reliability (Dunn et al., 2013; Rammstedt & Beierlein, 2014). Also, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were provided in such cases for comparison reasons because most of the previous studies with these scales reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficients.

SPSS 25.0 was used to calculate means, standard deviations, percentages, and correlation coefficients were calculated. Slight differences in correlation coefficients and betas are due to missing information on gender and age, which were not imputed. The prevalence of shopping addiction was calculated (in accordance with the cut-off based on a polythetic approach (i.e., scoring 4 [often] or 5 [always] on at least four of the seven items). The polythetic approach used in the present study is in line with modern psychiatric nosology (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Five hierarchical regression analyses were conducted where shopping addiction, stress, general health, sleep quality, and quality of life were dependent variables. Independent variables introduced in subsequent steps can be found in Tables 2 and 3. In the regression analysis, where shopping addiction was the dependent variable, demographic variables were entered first, followed by the Big Five personality traits, then self-esteem and perceived narcissism which are intricately associated (Chen et al., 2004; Fatfouta & Schröder-Abé, 2018; Stronge et al., 2016; Zeigler-Hill, 2006), and finally social anxiety and loneliness as social functioning variables together with self-efficacy as agency related self-concept variable linked to successful social interactions (Di Blas et al., 2017) were entered in the last step. Such an order allows for comparing the results of preceding steps with the previously published studies on different samples, as well as for examining the amount of variance explained by different classes of variables (Big Five personality traits, perceived narcissism and self-esteem, self-efficacy and social functioning) above and beyond previously investigated variables. In the case of other regression analyses, shopping addiction was entered in the first step to examine how it is related to the dependent variables before and after controlling for other variables. The other steps follow the previously described logic. For all linear regression analyses, preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure no violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity, multicollinearity, and homoscedasticity. All tests were two-tailed, and the significance level was set to α = .05. The tested models included multiple variables which may raise concerns about need for correction for multiple comparisons. However, it is generally recommended in the current statistical literature that simply describing what tests of significance have been performed, and why, is the best way of dealing with multiple comparisons (please see a detailed discussion for example in Gelman et al., 2012).

Results

Factor Analysis

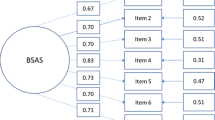

The model with one factor of shopping addiction showed following fit indices: χ2/df = 25.52, CFI = .972, TLI = .957, RMSEA = .146 (90% CI = .133–.160). Due to the lack of acceptable model fit, residuals of the first and second item were correlated on the basis of modification indices similarly to the original study in which it was explained that these two items both reflected inner thoughts or states (Andreassen et al., 2015). It was also argued that these items in scales based on addiction components model are often operationalized without proper clinical validity and are reflective more of a normal high-engagement behavior (Atroszko et al., 2017; Atroszko et al., 2018). The modified model had a good fit: χ2/df = 4.02, CFI = .997, TLI = .995, RMSEA = .051 (90% CI = .037–.066). Table 1 shows the standardized regression weights for each of the items in both models as well as the percentage of respondents (with 95% CI) scoring 4 (often) or 5 (always) on a particular item. The correlation between the residuals of the first and second item was .51.

Prevalence

The prevalence of shopping addiction in the current sample was estimated at 3.5% (n = 40). Table 2 presents the number of items with a score of 4 (often) or 5 (always).

Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 presents mean scores, standard deviations, percentages, and correlation coefficients of the study variables.

Predictors of Shopping Addiction

Regression analysis for shopping addiction (see Table 4) showed that the independent variables explained a total of 11.5% of the variance of shopping addiction, F12,1004 = 10.89, p < .001. Significant independent variables in Step 4 were gender (β = −.11), showing that females score higher on shopping addiction, age (β = .12), extraversion (β = .10), agreeableness (β = −.11), perceived narcissism (β = .16), self-efficacy (β = −.10) and social anxiety (β = .08).

Shopping Addiction as a Predictor of Well-Being

Regression analysis for stress (see Table 5) showed that the independent variables explained a total of 36.0% of the variance of stress, F13,1001 = 43.40, p < .001. Significant independent variables in Step 5 were emotional stability (β = −.13), self-esteem (β = −.30), self-efficacy (β = −.19), social anxiety (β = .08) and loneliness (β = .13).

Regression analysis for general health (see Table 5) showed that the independent variables explained a total of 15.1% of the variance of general health, F13,1003 = 13.69, p < .001. Significant independent variables in Step 5 were shopping addiction (β = −.13), age (β = −.10), and self-esteem (β = .31).

Regression analysis for sleep quality (see Table 5) showed that the independent variables explained a total of 14.5% of the variance of sleep quality, F13,999 = 13.07, p < .001. Significant independent variables in Step 5 were shopping addiction (β = −.10), emotional stability (β = .10), openness to experience (β = −.08), and self-esteem (β = .32).

Regression analysis for quality of life (see Table 5) showed that the independent variables explained a total of 35.5% of the variance of quality of life, F13,1002 = 42.49, p < .001. Significant independent variables in Step 5 were gender (β = −.10), showing that females score higher on quality of life, age (β = −.08), extraversion (β = .10) self-esteem (β = .33), self-efficacy (β = .24) and loneliness (β = −.14).

Discussion

Psychometric Properties of BSAS

The modified one-factor solution with correlated error terms of the first two items had an acceptable fit. This is congruent with results from studies on other addiction scales focusing on core addiction components. The possible explanation for correlated error terms could be the high time and energy investment, that besides compulsion, is typically present in behavior measured by these scales and especially represented by these items (Atroszko, 2018; Atroszko et al., 2017; Atroszko et al., 2018). The factor loadings in all cases were significant with standardized values above .40. The scale also showed adequate reliability (H1 substantiated). BSAS scores were positively related to female gender and age, which is congruent with other research on compulsive buying and gender, and our assumptions related to age in the present sample (H2 substantiated).

Shopping Addiction and Personality

Shopping addiction showed slightly different patterns of relationships with personality in zero-order correlations in comparison to the regression model. This needs to be taken into account when interpreting the results as it may reflect mediation effects (e.g., the effect of neuroticism mediated by social anxiety; see Lawendowski et al., 2019) or effects of common factors shared by different constructs such as anxiety. Shopping addiction correlated positively with neuroticism and negatively with agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. These results are to a large extent congruent with previous data (Andreassen et al., 2015; Balabanis, 2002). However, in the final regression model, shopping addiction showed a significant positive relationship only with extraversion and negative relationship with agreeableness (H3 substantiated). The attenuation of the relationships of shopping addiction with conscientiousness and neuroticism may be due to the presence in the model of other variables, including agency related (self-efficacy) and emotion-related (social anxiety, self-esteem). Low agreeableness, however, showed a positive relationship with shopping addiction even after controlling for all the other variables. The facets of agreeableness include trust, straightforwardness, altruism, compliance, modesty and tender-mindedness (Costa et al., 1991), which are directly related to the quality of interpersonal relationships, strategies in resolving conflicts, tendencies to prosocial behavior and well-being in general (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Graziano et al., 2007; Jensen-Campbell & Graziano, 2001; Neyer & Voigt, 2004). Low agreeableness is related to lower satisfaction with intimate relationships (Laursen & Richmond, 2014; Malouff et al., 2010). Reduced satisfaction from relationships may be the reason for turning to different types of sensation seeking. Shopping then could be approached as a search for a substitute for intense feelings that usually accompany close relationships.

Shopping Addiction, Well-Being, Self-Concept and Social Functioning

Zero-order correlations showed that shopping addiction was related to higher perceived stress, worse general health, sleep quality, and general quality of life (H4 substantiated). After controlling for all personality, self-concept and social functioning variables in the regression model, shopping addiction was shown to be still related to poor quality of sleep as well as worse general health. However, the relationships were attenuated, and in the case of stress and general quality of life, they were nonsignificant, suggesting that some other variables related to shopping addiction such as self-efficacy, agreeableness or social anxiety may explain at least some facets of decreased well-being. Due to limited variance, single-item measure of a general quality of life representing a global concept of life evaluation may not capture more nuanced relationships of this variable with other variables (see Atroszko, 2015; Atroszko et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the results indicate a consistent link between shopping addiction and impaired well-being. There is limited data on the relationship of shopping addiction with variables such as general health, quality of life, or stress. However, they seem crucial in differentiating between occasional impulsive purchases, leisure shopping, and shopping addiction. Unlike the impulse and leisure buying, shopping addiction should be related to significant, persistent impairment in functioning. Buying might be a response to chronic stress, but in consequence, cumulating debts, neglecting social relationships and health, and generally ignoring the need for developing healthy coping strategies can cause further stress, sleep problems, and deterioration of health. Whether the decreased quality of life is a motive, a consequence, or both, it suggests problems with adaptive coping in each case. Since harm caused by the behavior is one of the key features in conceptualizing a behavioral addiction (Grant et al., 2010), these results suggest that compulsive shopping fulfills that criterium.

Perceived narcissism was also positively related to shopping addiction, whereas self-esteem and self-efficacy were negatively related to it (H5 substantiated). This is congruent with previous studies on shopping addiction (Davenport et al., 2012; Jiang & Shi, 2016; Ridgway et al., 2008; Rose, 2007) as well as other addictions (Atroszko et al., 2018; Iskender & Akin, 2010; Lichtenstein et al., 2014). The results obtained in the present study indicate that people with shopping addiction do not have sufficient social competences. In the case of narcissists, their self-esteem needs constant reinforcement from an external point of reference (Baumeister & Vohs, 2001; Campbell & Green, 2008). It is possible that since they are unable to obtain self-enhancement from interacting with others, they engage in a substitute, indirect form of self-validation through increasing their perceived social status.

In the regression model, self-esteem was not significantly related to shopping addiction probably due to the presence in the model of other variables related to self-concept, including narcissism and self-efficacy. The negative relationship of shopping addiction and self-efficacy shows that individuals with compulsive buying question their ability to manage different situations and have not developed effective strategies of coping with stress, which is why they need to relieve negative emotions through maladaptive behavior. These findings seem very important from the perspective of designing interventions. Modifying self-efficacy can result in behavior change, which is vital in addiction therapy (Webb et al., 2010).

Apart from the negative relationship of shopping addiction with agreeableness, it was also positively correlated to social anxiety and loneliness, which further implies that people who engage in excessive spending have problems with maintaining close relationships (H6 substantiated). This is congruent with previous studies on shopping addiction (O’Guinn & Faber, 1989; Schlosser et al., 1994; Wang & Xiao, 2009) as well as other addictions (Bozoglan et al., 2013; Dobrean & Păsărelu, 2016; Ste-Marie et al., 2002). Loneliness was not a significant predictor of shopping addiction within the regression model. This suggests that some other variables in the model (likely social anxiety or agreeableness) account for this relationship. However, these findings provide an empirical insight into the social functioning of individuals with shopping addiction. Loneliness and social anxiety prevent people from seeking social support when dealing with different problems. As a result, lack of social support fosters maladaptive coping through, in this case, excessive shopping. At the same time, addiction causes conflicts with the social environment and encourages further isolation from close ones. This effect can be amplified by low agreeableness that is associated with proneness to conflict. More detailed analyses of social predictors of shopping addiction are apparently required.

Prevalence

Prevalence of shopping addiction in the present sample based on the polythetic cut-off score was 3.5%, which is similar to more conservative estimates in previous studies (Black, 2007; Koran et al., 2006; Maraz et al., 2016). Nevertheless, this diagnostic threshold is as for now to a large extent arbitrary, and more systematic effort to establish and validate a psychometric cut-off is warranted.

Strengths and Limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the relative contribution of a wide range of relevant personality characteristics and social functioning variables to shopping addiction, and the unique variance which this addiction explains in different facets of well-being above and beyond these variables known to be risk factors of impaired psychosocial functioning. The present study comprised a relatively large sample size providing high statistical power and valid and reliable psychometric tools were included. The use of ultra-short scales allowed to investigate a fairly complex model with numerous variables (both potential antecedents and consequences). This likely reduced the threats to the validity related to the effects of the burden associated with longer measures. Consequently, the study significantly adds to the existing literature on behavioral addictions, and provides further insights into the nature of shopping addiction, and its relationship to health and psychological well-being. The study also has some limitations that should be mentioned. All data were self-reported, which leaves it open to the usual weaknesses of such data (e.g., common method, social desirability, and recall biases). The use of ultra-short measures of personality and well-being probably had an effect on the limited range of covariance between variables and attenuation of real effect sizes. These scales have also somewhat lower reliability to their longer counterparts, including only test-retest estimates of single-item measures; therefore, more measurement error can be expected. Moreover, while some constructs, such as self-efficacy, are more easily measured with short scales, other more complex, multidimensional and ambiguous constructs such as narcissism (Fatfouta & Schröder-Abé, 2018) most likely require more attention and in-depth investigation in relation to shopping addiction in the future studies. Also, Agreeableness and Openness to Experience scales showed lower reliability estimates than in previous studies. For this reason, the conclusions concerning these constructs need to be interpreted cautiously, and future studies should use longer scales with better reliability. Due to the large sample size, some of the correlation coefficients are still significant despite their low values (for example, shopping addiction and loneliness), therefore they may have limited substantive meaning. The study also did not account for materialism. Previous research showed that it explains up to 26% of the variance of compulsive buying (Dittmar, 2005). Materialism is associated with many of the variables in the present study (e.g., Dittmar et al., 2014). The lack of materialism in our analyses does not allow to draw any conclusions concerning potential added predictive value of our model above and beyond materialism, as well as the amount of unique variance of compulsive buying predicted by materialism above and beyond the currently investigated model. It is possible that previous estimates of the role of materialism were so high because the study did not account for personality and self-concept. For example, high levels of materialism are related to high neuroticism and low agreeableness (Watson, 2014). Previous research examining the relationships between compulsive buying, temperament, materialism, and depression indicate that the role of materialism might differ depending on the population. In a clinical sample, depression explained the additional variance in compulsive buying above and beyond materialism (Müller et al., 2014), which was not true for the sample of university students, in which temperament and materialism explained compulsive buying after controlling for the depressive symptoms (Claes et al., 2010). Therefore, we recommend that future studies should investigate materialism and currently investigated variables as predictors of compulsive buying within a single model, including the potential mediating effects of materialism between personality and shopping addiction. Furthermore, as the Polish sample was not representative, this puts restrictions on the generalizability to other populations.

Conclusions and Future Research Directions

The present study showed that the Polish adaptation of the Bergen Shopping Addiction Scale has good validity (factorial, and concurrent with particular personality traits, self-concept, social functioning and well-being) and reliability and therefore, can be used as a tool to investigate problematic spending. The study provides an outline of the features that could predispose to shopping addiction, including potential specific personality risk factors. The risk factors among students comprise being female, older, extravertive, and low in agreeableness, as well as considering oneself more narcissistic, having a low sense of self-efficacy and high social anxiety. In light of these results, it seems that shopping dependent individuals crave for social interactions and admiration, but due to low agreeableness, social anxiety and lack of proper skills, they are not willing and/or they do not know how to compromise with others in order to obtain approval; therefore, they turn to shopping as a substitute for affirmation and positive feelings.

The study also showed that shopping addiction may have adverse effects on psychosocial functioning that include impaired quality of life, general health, sleep quality, and perceived level of stress. This is congruent with the criterium for behavioral addiction requiring significant harm caused by the behavior. However, some of the personality factors may account, at least to some degree, for the negative relationship between shopping addiction and well-being. In general, the results provide some support to the notion that compulsive buying is a behavioral addiction, and that it is a result of ineffective coping and dissatisfying social life. In this context, knowledge of common and specific coping-related personality risk factors may allow for the development of better designed early prevention and intervention programs.

Further research should focus on the more thorough exploration of the psychometric properties of the Bergen Shopping Addiction Scale, including the explanation for correlated error terms for items. In the light of an ongoing discussion about the nature of behavioral addictions, future studies should aim at investigating the addictive status of shopping, including temporal stability, and conceivably a broader consensus on the exact diagnostic criteria. This should include gathering more objective data through studies on cognitive, neurobiological, and genetic correlates to shopping addiction, or observational studies of behavior/responses of people with shopping addiction. In terms of personality, low agreeableness emerges as a specific risk factor for shopping addiction. A particular issue seems to be the question of whether individuals struggling with shopping addiction are not willing or they do not know how to compromise with others in order to develop satisfying social relationships. From this perspective, the relation of impulsivity and sensation-seeking with shopping addiction requires more systematic investigation as these traits are common for both substance use diorders and behavioral addictions, and seem particularly relevant for compulsive shopping in comparison to internet gaming disorder, social networking sites addiction, work addiction or exercise addiction (Grant et al., 2010). Conducting the longitudinal study on a representative sample of young adults would also be recommended to examine developmental risk factors of shopping addiction.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the fact that the participants were not informed that the dataset will be openly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Achtziger, A., Hubert, M., Kenning, P., Raab, G., & Reisch, L. (2015). Debt out of control: The links between self-control, compulsive buying, and real debts. Journal of Economic Psychology, 49, 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2015.04.003.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

Andreassen, C. S. (2014). Shopping addiction: An overview. Journal of the Norwegian Psychological Association, 51, 194–209.

Andreassen, C. S., Griffiths, M. D., Gjertsen, S. R., Krossbakken, E., Kvam, S., & Pallesen, S. (2013). The relationships between behavioral addictions and the five-factor model of personality. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2(2), 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1556/jba.2.2013.003.

Andreassen, C. S., Griffiths, M. D., Pallesen, S., Bilder, R. M., Torsheim, T., & Aboujaoude, E. (2015). The Bergen shopping addiction scale: Reliability and validity of a brief screening test. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01374.

Atroszko, P. A. (2015). The structure of study addiction: Selected risk factors and the relationship with stress, stress coping and psychosocial functioning (unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Gdansk, Poland.

Atroszko, P. A. (2018). Commentary on: The Bergen study addiction scale: Psychometric properties of the Italian version. A pilot study. Theoretical and methodological issues in the research on study addiction with relevance to the debate on conceptualising behavioural addictions. Psychiatria i Psychologia Kliniczna, 18(3), 276–282. https://doi.org/10.15557/pipk.2018.0034.

Atroszko, P. A. (2019). Work addiction as a behavioural addiction: Towards a valid identification of problematic behaviour. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 53(4), 284–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867419828496.

Atroszko, P. A., Andreassen, C. S., Griffiths, M. D., & Pallesen, S. (2015). Study addiction — A new area of psychological study: Conceptualization, assessment, and preliminary empirical findings. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(2), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.007.

Atroszko, P. A., Andreassen, C. S., Griffiths, M. D., & Pallesen, S. (2016a). Study addiction: A cross-cultural longitudinal study examining temporal stability and predictors of its changes. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(2), 357–362. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.024.

Atroszko, P. A., Andreassen, C. S., Griffiths, M. D., & Pallesen, S. (2016b). The relationship between study addiction and work addiction: A cross-cultural longitudinal study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(4), 708–714. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.076.

Atroszko, P. A., Bagińska, P., Mokosińska, M., Sawicki, A., & Atroszko, B. (2015). Validity and reliability of single item self-report measures of general quality of life, general health and sleep quality. In M. McGreevy & R. Rita (Eds.), Proceedings of the 4th biannual CER comparative European research conference (pp. 207–211). Sciemcee Publishing.

Atroszko, P. A., Balcerowska, J. M., Bereznowski, P., Biernatowska, A., Pallesen, S., & Andreassen, C. S. (2018). Facebook addiction among polish undergraduate students: Validity of measurement and relationship with personality and well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 85, 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.001.

Atroszko, P. A., Sawicki, A., Sendal, L., & Atroszko, B. (2017). Validity and reliability of single-item self-report measure of global self-esteem. In M. McGreevy & R. Rita (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th biannual CER comparative European research conference (pp. 120–123). Sciemcee Publishing.

Balabanis, G. (2002). The relationship between lottery ticket and scratch-card buying behaviour, personality and other compulsive behaviours. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 2(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.86.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co.

Baumeister, R., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Narcissism as addiction to esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 12(4), 206–210.

Berczik, K., Szabó, A., Griffiths, M. D., Kurimay, T., Kun, B., Urbán, R., & Demetrovics, Z. (2012). Exercise addiction: Symptoms, diagnosis, epidemiology, and etiology. Substance Use & Misuse, 47(4), 403–417. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2011.639120.

Billieux, J., Maurage, P., Lopez-Fernandez, O., Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Can disordered Mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Current Addiction Reports, 2(2), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0054-y.

Billieux, J., Rochat, L., My Lien Rebetez, M., & Van Der Linden, M. (2008). Are all facets of impulsivity related to self-reported compulsive buying behavior? Personality and Individual Differences, 44(6), 1432–1442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.12.011.

Black, D. W. (2007). A review of compulsive buying disorder. World Psychiatry, 6(1), 14–18.

Black, D. W., Repertinger, S., Gaffney, G. R., & Gabel, J. (1998). Family history and psychiatric comorbidity in persons with compulsive buying: Preliminary findings. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(7), 960–963. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.155.7.960.

Bozoglan, B., Demirer, V., & Sahin, I. (2013). Loneliness, self-esteem, and life satisfaction as predictors of internet addiction: A cross-sectional study among Turkish university students. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 54(4), 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12049.

Brown, R. I. F. (1993). Some contributions of the study of gambling to the study of other addictions. In W. R. Eadington & J. Cornelius (Eds.), Gambling behavior and problem gambling (pp. 341–372). University of Nevada Press.

Buckner, J. D., & Schmidt, N. B. (2008). Marijuana effect expectancies: Relations to social anxiety and marijuana use problems. Addictive Behaviors, 33(11), 1477–1483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.017.

Campbell, W. K., & Green, J. D. (2008). Narcissism and interpersonal self-regulation. In J. V. Wood, A. Tesser, & J. G. Holmes (Eds.), The self and social relationships (pp. 73–94). Psychology Press.

Caplan, S. E. (2007). Relations among loneliness, social anxiety, and problematic internet use. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 10(2), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9963.

Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2004). General self-efficacy and self-esteem: Toward theoretical and empirical distinction between correlated self-evaluations. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 25(3), 375–395. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.251.

Christenson, G. A., Faber, R. J., de Zwaan, M., Raymond, N. C., Specker, S. M., Ekern, M. D., Mackenzie, T. B., Crosby, R. D., Crow, S. J., & Eckert, E. D. (1994). Compulsive buying: Descriptive characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 55(1), 5–11.

Claes, L., Bijttebier, P., Van Den Eynde, F., Mitchell, J. E., Faber, R., De Zwaan, M., & Mueller, A. (2010). Emotional reactivity and self-regulation in relation to compulsive buying. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(5), 526–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.020.

Claes, L., & Müller, A. (2017). Resisting temptation: Is compulsive buying an expression of personality deficits? Current Addiction Reports, 4(3), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-017-0152-0.

Clark, M., & Calleja, K. (2008). Shopping addiction: A preliminary investigation among Maltese university students. Addiction Research & Theory, 16(6), 633–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066350801890050.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

Costa, P. T., Mccrae, R. R., & Dye, D. A. (1991). Facet scales for agreeableness and conscientiousness: A revision of the NEO personality inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 12(9), 887–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(91)90177-d.

Da Silva, T. L. (2015). Compulsive buying: Psychopathological condition, coping strategy or sociocultural phenomenon? A review. Journal of Addictive Behaviors, Therapy & Rehabilitation, 04(02). https://doi.org/10.4172/2324-9005.1000137.

Dąbkowska, M. (2008). Wybrane aspekty lęku u ofiar przemocy domowej. Psychiatria, 5(3), 91–98.

Davenport, K., Houston, J. E., & Griffiths, M. D. (2012). Excessive eating and compulsive buying Behaviours in women: An empirical pilot study examining reward sensitivity, anxiety, impulsivity, self-esteem and social desirability. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10(4), 474–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-011-9332-7.

DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 197–229. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.124.2.197.

Di Blas, L., Grassi, M., Carnaghi, A., Ferrante, D., & Calarco, D. (2017). Within-person and between-people variability in personality dynamics: Knowledge structures, self-efficacy, pleasure appraisals, and the big five. Journal of Research in Personality, 70, 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2017.06.002.

Dittmar, H. (2005). Compulsive buying - a growing concern? An examination of gender, age, and endorsement of materialistic values as predictors. British Journal of Psychology, 96(4), 467–491. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712605x53533.

Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., & Kasser, T. (2014). The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(5), 879–924. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037409.

Dobrean, A., & Păsărelu, C. R. (2016). Impact of social media on social anxiety: A systematic review. In F. Durbano & B. Marchesi (Eds.), New developments in anxiety disorders (pp. 129–149). InTech. https://doi.org/10.5772/65188.

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2013). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046.

Enders, C. K. (2001). A primer on maximum likelihood algorithms available for use with missing data. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 8(1), 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0801_7.

Faber, R. J. (2010). Impulsive and compulsive buying. In J. N. Sheth & N. K. Malhotra (Eds.), Wiley international encyclopedia of marketing. Wiley.

Faber, R. J., & O’Guinn, T. C. (1992). A clinical screener for compulsive buying. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 459. https://doi.org/10.1086/209315.

Faber, R. J., & Vohs, K. D. (2004). To buy or not to buy?: Self-control and self-regulatory failure in purchase behavior. In R. F. Baumeister & K. D. Vohs (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 509–524). Guilford Press.

Fatfouta, R., & Schröder-Abé, M. (2018). Agentic to the core? Facets of narcissism and positive implicit self-views in the agentic domain. Journal of Research in Personality, 74, 78–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.02.006.

Fattore, L., Melis, M., Fadda, P., & Fratta, W. (2014). Sex differences in addictive disorders. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 35(3), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.04.003.

Fineberg, N. A., Demetrovics, Z., Stein, D. J., Ioannidis, K., Potenza, M. N., Grünblatt, E., et al. (2018). Manifesto for a European research network into problematic usage of the internet. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 28(11), 1232–1246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.08.004.

Gelman, A., Hill, J., & Yajima, M. (2012). Why we (usually) don't have to worry about multiple comparisons. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 5(2), 189–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2011.618213.

Glatt, M. M., & Cook, C. C. (1987). Pathological spending as a form of psychological dependence. Addiction, 82(11), 1257–1258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb00424.x.

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1.

Granero, R., Fernández-Aranda, F., Baño, M., Steward, T., Mestre-Bach, G., Del Pino-Gutiérrez, A., et al. (2016). Compulsive buying disorder clustering based on sex, age, onset and personality traits. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 68, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.03.003.

Grant, J. E., Potenza, M. N., Weinstein, A., & Gorelick, D. A. (2010). Introduction to behavioral addictions. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(5), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2010.491884.

Graziano, W. G., Habashi, M. M., Sheese, B. E., & Tobin, R. M. (2007). Agreeableness, empathy, and helping: A person × situation perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(4), 583–599. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.4.583.

Griffiths, M. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359.

Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Behavioural addiction and substance addiction should be defined by their similarities not their dissimilarities. Addiction, 112(10), 1718–1720. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13828.

Griffiths, M. D., Demetrovics, Z., & Atroszko, P. A. (2018). Ten myths about work addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7, 845–857. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.05.

Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Social networking addiction. Behavioral Addictions, 119–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-407724-9.00006-9.

Hanley, A., & Wilhelm, M. S. (1992). Compulsive buying: An exploration into self-esteem and money attitudes. Journal of Economic Psychology, 13(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4870(92)90049-d.

Harvanko, A., Lust, K., Odlaug, B. L., Schreiber, L. R., Derbyshire, K., Christenson, G., & Grant, J. E. (2013). Prevalence and characteristics of compulsive buying in college students. Psychiatry Research, 210(3), 1079–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.08.048.

Hausenblas, H. A., & Symons Downs, D. (2002). How much is too much? The development and validation of the exercise dependence scale. Psychology & Health, 17(4), 387–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044022000004894.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027504268574.

Iskender, M., & Akin, A. (2010). Social self-efficacy, academic locus of control, and internet addiction. Computers & Education, 54(4), 1101–1106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.10.014.

Jacobs, D. F. (1986). A general theory of addictions: A new theoretical model. Journal of Gambling Behavior, 2(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01019931.

Jensen-Campbell, L. A., & Graziano, W. G. (2001). Agreeableness as a moderator of interpersonal conflict. Journal of Personality, 69(2), 323–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00148.

Jeong, E. J., & Kim, D. H. (2011). Social activities, self-efficacy, game attitudes, and game addiction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 14(4), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0289.

Jiang, Z., & Shi, M. (2016). Prevalence and co-occurrence of compulsive buying, problematic internet and mobile phone use in college students in Yantai, China: Relevance of self-traits. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1211. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3884-1.

Kardefelt-Winther, D., Heeren, A., Schimmenti, A., Rooij, A. V., Maurage, P., Carras, M., ... Billieux, J. (2017). How can we conceptualize behavioural addiction without pathologizing common behaviours? Addiction, 112(10), 1709–1715. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13763.

Konkolÿ Thege, B. (2017). The coping function of mental disorder symptoms: Is it to be considered when developing diagnostic criteria for behavioural addictions? Addiction, 112(10), 1716–1717. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13816.

Konrath, S., Meier, B. P., & Bushman, B. J. (2014). Development and validation of the single item narcissism scale (SINS). PLoS One, 9, e103469. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103469.

Koran, L., Faber, R. J., Aboujaoude, E., Large, M., & Serpe, R. (2006). Estimated prevalence of compulsive buying behavior in the United States. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(1), 1806–1812. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.163.10.1806.

Krueger, D. W. (1988). On compulsive shopping and spending: A psychodynamic inquiry. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 42(4), 574–584. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1988.42.4.574.

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2011). Online social networking and addiction—A review of the psychological literature. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8(9), 3528–3552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8093528.

Laursen, B., & Richmond, A. (2014). Relationships: Commentary: Personality, relationships, and behavior problems: Its hard to be disagreeable. Journal of Personality Disorders, 28(1), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2014.28.1.143.

Lawendowski, R., Bereznowski, P., Wróbel, W. K., Kierzkowski, M., & Atroszko, P. A. (2019). Study addiction among musicians: Measurement, and relationship with personality, social anxiety, performance, and psychosocial functioning. Musicae Scientiae, 24, 449–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864918822138.

Lejoyeux, M., & Weinstein, A. (2010). Compulsive buying. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(5), 248–253. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2010.493590.

Lichtenstein, M. B., Christiansen, E., Elklit, A., Bilenberg, N., & Støving, R. K. (2014). Exercise addiction: A study of eating disorder symptoms, quality of life, personality traits and attachment styles. Psychiatry Research, 215(2), 410–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.11.010.

Lichtenstein, M. B., Malkenes, M., Sibbersen, C., & Hinze, C. J. (2019). Work addiction is associated with increased stress and reduced quality of life: Validation of the Bergen work addiction scale in Danish. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12506.

Liebowitz, M. R. (1987). Social phobia. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry, 22, 141–173. https://doi.org/10.1159/000414022.

Magee, A. (1994). Compulsive buying tendency as a predictor of attitudes and perceptions. In C.T. Allen and D.R. John (eds). Advances in Consumer Research, 21, 590–594.

Malouff, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Schutte, N. S., Bhullar, N., & Rooke, S. E. (2010). The five-factor model of personality and relationship satisfaction of intimate partners: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(1), 124–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.09.004.

Maraz, A., Eisinger, A., Hende, B., Urbán, R., Paksi, B., Kun, B., Kökönyei, G., Griffiths, M. D., & Demetrovics, Z. (2015). Measuring compulsive buying behaviour: Psychometric validity of three different scales and prevalence in the general population and in shopping centres. Psychiatry Research, 225(3), 326–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.080.

Maraz, A., Griffiths, M. D., & Demetrovics, Z. (2016). The prevalence of compulsive buying: A meta-analysis. Addiction, 111(3), 408–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13223.

Marlatt, G. A., Baer, J. S., & Quigley, L. A. (1995). Self-efficacy and addictive behavior. In A. Bandura (Ed.), Self-efficacy in changing societies (pp. 289–315). Cambridge University Press.

Marmet, S., Studer, J., Rougemont-Bücking, A., & Gmel, G. (2018). Latent profiles of family background, personality and mental health factors and their association with behavioural addictions and substance use disorders in young Swiss men. European Psychiatry, 52, 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.04.003.

Mccormick, R. A., Dowd, E., Quirk, S., & Zegarra, J. H. (1998). The relationship of neo-pi performance to coping styles, patterns of use, and triggers for use among substance abusers. Addictive Behaviors, 23(4), 497–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00005-7.

McElroy, S. L., Keck, P. E., Pope Jr., H. G., Smith, J. M. R., & Strakowski, S. (1994). Compulsive buying: A report of 20 cases. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 55(6), 242–248.

McElroy, S. L., Satlin, A., Pope, H. G., Keck, P. E., & Hudson, J. (1991). Treatment of compulsive shopping with antidepressants: A report of three cases. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 3(3), 199–204. https://doi.org/10.3109/10401239109147991.

Mestre-Bach, G., Steward, T., Jiménez-Murcia, S., & Fernández-Aranda, F. (2017). Differences and similarities between compulsive buying and other addictive behaviors. Current Addiction Reports, 4(3), 228–236.

Mikołajczak-Degrauwe, K., Brengman, M., Wauters, B., & Rossi, G. (2012). Does personality affect compulsive buying? An Application of the Big Five Personality Model. Psychology - Selected Papers. https://doi.org/10.5772/39106.

Mowen, J. C., & Spears, N. (1999). Understanding compulsive buying among college students: A hierarchical approach. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 8(4), 407–430. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp0804_03.

Müller, A., Mitchell, J. E., Crosby, R. D., Gefeller, O., Faber, R. J., Martin, A., ... Zwaan, M. D. (2010). Estimated prevalence of compulsive buying in Germany and its association with sociodemographic characteristics and depressive symptoms. Psychiatry Research, 180(2–3), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2009.12.001.

Müller, A., Brand, M., Claes, L., Demetrovics, Z., De Zwaan, M., Fernández-Aranda, F., ... Kyrios, M. (2019). Buying-shopping disorder—Is there enough evidence to support its inclusion in ICD-11? CNS Spectrums, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1092852918001323.

Müller, A., Claes, L., Georgiadou, E., Möllenkamp, M., Voth, E. M., Faber, R. J., ... De Zwaan, M. (2014). Is compulsive buying related to materialism, depression or temperament? Findings from a sample of treatment-seeking patients with CB. Psychiatry Research, 216(1), 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.012.

Müller, A., Claes, L., Mitchell, J. E., Wonderlich, S. A., Crosby, R. D., & De Zwaan, M. (2010). Personality prototypes in individuals with compulsive buying based on the big five model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(9), 930–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.020.

Müller, A., Mitchell, J. E., & De Zwaan, M. (2015). Compulsive buying. The American Journal on Addictions, 24(2), 132–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12111.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

Neyer, F. J., & Voigt, D. (2004). Personality and social network effects on romantic relationships: A dyadic approach. European Journal of Personality, 18(4), 279–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.519.

O’Guinn, T., & Faber, R. J. (1989). Compulsive buying: A phenomenological exploration. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(2), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1086/209204.

Orosz, G., Dombi, E., Andreassen, C. S., Griffiths, M. D., & Demetrovics, Z. (2016). Analyzing models of work addiction: Single factor and bi-factor models of the Bergen work addiction scale. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 14(5), 662–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-015-9613-7.

Otero-López, J. M., & Villardefrancos, E. (2014). Prevalence, sociodemographic factors, psychological distress, and coping strategies related to compulsive buying: A cross sectional study in Galicia, Spain. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-14-101.

Piquet-Pessôa, M., Ferreira, G. M., Melca, I. A., & Fontenelle, L. F. (2014). DSM-5 and the decision not to include sex, shopping or stealing as addictions. Current Addiction Reports, 1(3), 172–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-014-0027-6.

Potenza, M. N. (2014). Non-substance addictive behaviors in the context of DSM-5. Addictive Behaviors, 39(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.004.

Rammstedt, B., & Beierlein, C. (2014). Can’t we make it any shorter? The limits of personality assessment and ways to overcome them. Journal of Individual Differences, 35, 212–220. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000141.

Ridgway, N. M., Kukar-Kinney, M., & Monroe, K. B. (2008). An expanded conceptualization and a new measure of compulsive buying. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(4), 622–639. https://doi.org/10.1086/591108.

Roberts, J. A., & Jones, E. (2001). Money attitudes, credit card use, and compulsive buying among American college students. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 35(2), 213–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2001.tb00111.x.

Rose, P. (2007). Mediators of the association between narcissism and compulsive buying: The roles of materialism and impulse control. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21(4), 576–581. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164x.21.4.576.

Scheffer, J. (2002). Dealing with missing data. Research Letters in the Information and Mathematical Sciences, 3, 153–160 Retrieved December 15, 2018 from http://equinetrust.org.nz/massey/fms/Colleges/College%20of%20Sciences/IIMS/RLIMS/Volume03/Dealing_with_Missing_Data.pdf.

Schlosser, S., Black, D. W., Repertinger, S., & Freet, D. (1994). Compulsive buying. Demography, phenomenology, and comorbidity in 46 subjects. General Hospital Psychiatry, 16(3), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-8343(94)90103-1.

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99, 323–338. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338.

Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). NFER-NELSON.