Abstract

In this paper, we focused on the poorly understood and rarely researched relationship between resilience and narcissism, adopting the adjective-based measures of narcissism. We examine how levels of resilience are related to grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, based on a three-dimensional model of resilience (i.e., ecological resilience, engineering resilience, and adaptive capacity). Using self-report, cross-sectional data from a general Polish sample (N = 657), we found that grandiose narcissism was positively related to all three dimensions of resilience, while vulnerable narcissism was negatively related to them. Grandiose narcissism was most strongly associated with adaptive capacity where vulnerable narcissism was mostly strongly associated with engineering resilience. We discuss our findings in relation to the function of two forms of narcissism may yield different capacities for stress management and recovery after experiencing stressful events. Therefore, this research is focused on self-report and we look forward to expand our research by behavioral indices in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Narcissism is a well-examined trait in psychology (e.g., Krizan & Herlache, 2018; Miller et al., 2017). Despite various controversies in the concept and definition of this trait (Miller et al., 2017), researchers commonly agree that it is multidimensional, with different forms or dimensions (Krizan & Herlache, 2018), and different consequences for human functioning (Dufner et al., 2019). One of the most important distinctions is that of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism (Wink, 1991). Grandiose narcissism is typically conceptualised as self-absorbed self-aggrandisement (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001), while vulnerable narcissism refers to feelings of inadequacy and incompetence (Miller et al., 2011). The core of narcissistic personality is entitled self-importance (Krizan & Herlache, 2018) and feeling of uniqueness (Freis, 2018).

Grandiose narcissism is positively related to better psychological functioning, while vulnerable narcissism is related to poorer psychological functioning (Dufner et al., 2019; Sedikides, 2020 for review). However, mechanisms explaining these differences are less known, suggesting self-esteem as a crucial factor (Sedikides et al., 2004). In the current paper, we propose resilience as another important factor, explaining the difference between the levels of subjective well-being among people with high levels of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism.

Resilience can be understood as a personality trait (Maltby et al., 2015), defined as the ability to maintain equilibrium as a healthy state of the individual (Maltby et al., 2015, 2016). Therefore, we focus on resilience understood as an individual difference, contrary to that models which describe resilience as a feature of the social-ecological system (Folke et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2004). Coping effectively with traumatic life events, unexpected occurrences, stress (Holling, 1973; Maltby et al., 2015), and chronic pain (Sturgeon & Zautra, 2010) is the essence of resilience. Resilience correlates positively with mental health and subjective wellbeing (Davydov et al., 2010; Samani et al., 2007).

Maltby et al. (2015) proposed three-dimensional model of resilience, indicating engineering resilience as the ability of a person to recover, stabilize their mental or life state, and returning to equilibrium following any disturbance in everyday events. A person characterized by high level of engineering resilience is more capable to cope after occurrence of stressful event. Ecological resilience is the ability to resist disturbances while maintaining equilibrium, and not allowing to perturb stable mental state of the individual, while making necessary changes to our psychical defence mechanisms, it is also accompanied by self-confidence in one’s strengths. A person characterized by high level of ecological resilience resists stress more effectively, by keeping their stable state of mind against any disturbance. It means that stress does not bother such person as much as a person who has low level of ecological resilience. Adaptive capacity is the ability to adapt to unpleasant, hard or unstable conditions, to manage or accommodate to the change (Maltby et al., 2015; Walker et al., 2004) and general willingness to adapt across life (Maltby et al., 2016). An individual characterized by high level of adaptive capacity is more capable to face unpleasant situations by adapting his/her mind to them. For example, while moving out, it is easier for such person to accommodate to new surroundings.

There is a considerable amount of research on subjective well-being and narcissism (e.g., Dufner et al., 2019; Rose, 2002; Zuckerman & O’Loughlin, 2009). However, there is only a limited amount of research on narcissism and resilience (Buyl et al., 2017; Kauten et al., 2013), despite the fact that resilience has proved to exert an effect on life satisfaction (Samani et al., 2007), subjective well-being, and self-reported health (Maltby et al., 2015). Therefore, examining the relationship between narcissism and resilience may shed light on the capacity of narcissists to manage stress and recover after experiencing stressful events, supplementing the studies on psychological functioning and narcissism.

In the current paper, we examine the relationships between two forms of narcissism (i.e., grandiose and vulnerable; Miller et al., 2017) and three broad forms of resilience (i.e., engineering resilience, ecological resilience, and adaptive capacity; Maltby et al., 2015). These three dimensions of resilience have distinct personality correlates and are responsible for distinct aspects of coping with stress and adaptation to the environment. For instance, engineering resilience is related mostly to not experiencing negative emotional states, ecological resilience is based on feelings of self-confidence and perceived control under environment, and adaptive capacity is between them both, being weakly related both to emotions and to coping (Maltby et al., 2015). This distinction is particularly useful in examining how people with high grandiose and vulnerable narcissism could be resilient toward stressful events and adapt to the environment.

Resilience and Its Relationship with Psychological Functioning

The three original forms of system resilience (i.e. engineering resilience, ecological resilience, and adaptive capacity) were reformulated to describe resilience as a multi-dimensional personality trait (Maltby et al., 2015). All three dimensions of resilience correlated positively with subjective well-being and extraversion, correlated negatively with neuroticism, and they were uncorrelated to avoidance coping. Only engineering resilience and ecological resilience were positively related to approach coping. Engineering resilience correlated stronger to neuroticism than ecological resilience and adaptive capacity. Ecological resilience correlated positively also with agreeableness, and ecological resilience correlated positively with conscientiousness (Maltby et al., 2015). Adaptive capacity was uniquely positively related to openness to experience (Maltby et al., 2016).

The usefulness of distinguishing three separate dimensions of resilience has been revealed in their different nomological network (Maltby et al., 2015, 2016). Neuroticism is associated with experiencing negative emotional states, while extraversion is related to focus on others, activity and optimism (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Therefore, engineering resilience seems to be the most emotionally-based dimension of resilience (because strong negative relationship with neuroticism), and it seems less proactive aspect of coping with stressful events due to its weak correlation with extraversion and lack of correlation with approach coping. Ecological resilience seems to be crucial in active managing with environment, as it indicates the strongest relationships to coping and to subjective well-being. As adaptive capacity is responsible for adapting to the change rather than initializing any activity, itis a rather passive aspect of resilience. Congruent with this assumed passivity it is weakly correlated to subjective well-being, uncorrelated with physical health, and its relationship with coping strategies are weak (Maltby et al., 2015). Ecological resilience is responsible for recovery after stressful events, while adaptive capacity and engineering resilience are responsible for dealing with ongoing stress by accommodation (engineering resilience), and general readiness to accept changes (adaptive capacity; see Maltby et al., 2015, 2016). Therefore, all three dimensions could be divided into proactive and flexible, like ecological resilience and passive, unrelated to activity, like adaptive capacity and engineering resilience.

Conceptualisation of Narcissism and Its Relationship with Psychological Functioning and Resilience

Grandiose narcissism is considered as rather intrapersonally healthy (Dufner et al., 2019), because of its positive correlations with high self-esteem (Rohman et al., 2019), psychological health (Ng et al., 2014), and subjective well-being (Zuckerman & O’Loughlin, 2009). Grandiose narcissism is also positively correlated to extraversion and negatively correlated to agreeableness and neuroticism (Miller et al., 2011). Grandiose narcissism is also related to lower perceived stress, which may be important to a person’s health and well-being (Ng et al., 2014). Positive correlation between grandiose narcissism and subjective well-being is mostly due to the result of the mediating effect of self-esteem (Sedikides et al., 2004). In addition, self-enhancement is beneficial for intrapersonal adjustment, yet it is not beneficial for social functioning (Dufner et al., 2019). Grandiose narcissism has some important similarities to high self-esteem, especially assertiveness and agency (Hyatt et al., 2018). The way of perceiving others and themselves by narcissistic individuals and people with high self-esteem is different, as the former undervalue others and overvalue themselves, while the latter just value themselves in positive way (Brummelman et al., 2018). The differences between self-esteem and grandiose narcissism seem to be crucial for understanding why grandiose narcissists could indicate higher resilience, but also point to possible downsides in managing stressful events. Higher levels of agency could help in dealing with stressful events, but on the other hand biased perception of the self and others could lead to unrealistic beliefs in own capacity, and evoke conflicts with others. Finally, grandiose narcissism is associated with increased motivation to action, also under social pressure or under self-threat (Sedikides, 2020), which could result in higher levels of resilience.

Contrary to this, vulnerable narcissism is accompanied by shyness, the impulsiveness of aggressive behaviour (Freis et al., 2015), and low self-esteem (Rohmann et al., 2019). Vulnerable narcissist manifests higher levels of neuroticism and lower levels of extraversion and agreeableness (Miller et al., 2011). People characterized by this type of narcissism, like grandiose narcissism, are often self-absorbed and desire approval, but lack the skills needed to obtain them (Freis et al., 2015). Such a set of features is interpersonally maladaptive (Hill & Lapsley, 2011). In addition, people with higher levels of vulnerable narcissism have less psychological health and higher perceived stress (Ng et al., 2014), as well as many negative emotions and emotional lability (Hill & Lapsley, 2011). The crucial factor involved in poorer psychological functioning of the vulnerable narcissists, including lower resilience, could be lack of agency and low self-esteem (Rohmann et al., 2019), what makes them less resistant to self-threats (Sedikides, 2020).

According to the mask model of narcissism, narcissists are hypersensitive to ego-threats and they “mask” their fragile self via grandiosity and intrapersonal exploitativeness (Sedikides, 2020). Form of narcissism (i.e., grandiose versus vulnerable) could be associated with the strength of the reaction toward threat and the way how narcissistic individuals restore their equilibrium. Grandiose narcissists indicate higher self-promotion focus, while vulnerable narcissist indicate higher avoidance and self-protection focus (Krizan & Herlache, 2018), as such vulnerable narcissist react stronger and in more passive way to the threats, which could result in lower resilience (Sedikides, 2020).

To date, there is a limited amount of research on the relationship between narcissism and resilience. Moreover, former researchers (1) did not distinguish overly between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism (Kauten et al., 2013; Yun & Min, 2018); (2) used rather non-traditional methods for assessing narcissism (Buyl et al., 2017; Kauten et al., 2013); (3) examined specific populations, like adolescents (Yun & Min, 2018; Kauten et al., 2013), MBA students (Wu et al., 2019) or general directors in banks (Buyl et al., 2017). For instance, Kauten, et al. (2013) used only a questionnaire examining narcissism related to psychopathy (Antisocial Process Screening Device; Frick & Hare, 2001) among adolescents, and did not find a correlation between (grandiose) narcissism and resilience, while Buyl et al. (2017) assessed CEO’s narcissism basing on behavioural indicators, like the prominence of the CEO’s photograph in the annual report. Yun and Min (2018) also examined only adolescents, revealing a negative correlation between narcissism and resilience. Buyl et al. (2017) examined the grandiose narcissism of general directors in banks and their psychological resilience. However, the researchers discussed resilience levels based on the propensity to recover after business failures which may be prohibitively narrow. Wu et al. (2019) examined the relationship between Dark Triad and resilience in the context of sustainable entrepreneurial orientation, finding that narcissism was unrelated with psychological resilience.

The Current Study

The relationship between resilience and narcissism (especially narcissism subtypes) is poorly understood. Former research on resilience and narcissism used only one-dimensional models of resilience and narcissism examining mainly adolescents or specific professional groups (Buyl et al., 2017; Kauten et al., 2013). Former studies were limited to Western populations, which could be specific, at least in relation to narcissism (Foster et al., 2003). One of the important limitations of the former studies was the way how the trait narcissism was assessed. In the current study we decided to use the adjective-based measures of narcissism, namely Narcissistic Grandiosity Scale (Crowe et al., 2016) and Vulnerable Grandiosity Scale (Crowe et al., 2018). Using both of these scales allow for clear separation between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, and they indicate clear and strong associations with the most widely used scales measuring narcissism (Edershile et al., 2019).

People with high grandiose narcissism report higher levels of subjective well-being (Rose, 2002) and their tend to be proactive (Foster & Trimm, 2008), therefore we expect that they also indicate higher levels of resilience. Because grandiose narcissists have high levels of activity and self-confidence (Rohmann et al., 2019), and their enhanced subjective well-being is mostly a function of their higher self-esteem (Sedikides et al., 2004) we expect that they manifest especially higher levels of ecological resilience as that dimension of resilience is related to activity and self-confidence.

As people with high vulnerable narcissism indicate lower levels of subjective well-being, mostly due to experiencing higher levels of negative emotions (Hill & Lapsey, 2011; Rose, 2002), we expect that they indicate lower levels of resilience. We expect that vulnerable narcissists manifest especially low levels of engineering resilience, as this aspect of resilience trait seems to be a protective factor against experiencing negative emotional states. People with high vulnerable narcissism report problems with their emotional states (Hill & Lapsley, 2011) and increased levels of neuroticism (Miller et al., 2011), so that we predict that their lower levels of resilience manifests mostly in emotional aspect.

Material and Methods

Participants and Procedure

We administered a two-wave survey to a general sample of 1100 Polish adults via the Ariadna online research panel. The waves were separated by 1 week. We separated measuring dependent and independent variables to control common-method bias and used randomized order of scales for each participant (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Our final sample comprised 657 participants: 372 women, 285 men (Mage = 45.31 years, SD = 15.38). Aged 18 to 82 after excluding 443 respondents who did not take part in the second wave or failed to answer correctly an one of attention check item (e.g., ‘Please select response option 5’). Respondents were rewarded by loyalty points in Ariadna online research panel. All procedures were approved by the institutional ethics board (KEiB – 10/2018). Data are available at https://osf.io/2xeyb/.

Measures

Vulnerable Narcissism

We assessed vulnerable narcissism with a one-dimensional 11-item adjective scale – Narcissistic Vulnerability Scale (e.g., ‘Underestimated’ or ‘Ashamed’; Crowe et al., 2018). The scale was translated and back translated for the purpose of current study (see Supplementary Materials). The response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Grandiose Narcissism

We assessed grandiose narcissism with a one-dimensional 13-item adjective scale – Narcissistic Grandiosity Scale (e.g., ‘Perfect’ or ‘Heroic’; Crowe et al., 2016). The scale was translated and back translated for the purpose of current study (see Supplementary Materials). The response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Resilience

We assessed resilience with the EEA Resilience Scale which contains three subscales: Ecological resilience (e.g., ‘I give my best effort no matter what the outcome may be’); engineering resilience (e.g., ‘Does not take a long time to recover’) and adaptive capacity (e.g., ‘I enjoy dealing with new and unusual situations’). The EEA is 12-item measure (Maltby, Day, & Hall, 2015; see Maltby et al. 2016; Sękowski et al, 2018, for the Polish version). The response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Higher scores on each of the resilience subscales indicate higher level of resilience.

Results

Descriptive Statistics, Internal Consistency Estimates, and Zero-Order Correlations

Descriptive statistics, reliability estimates, and zero-order correlations for all variables are presented in Table 1. We also conducted a post hoc power analysis instead of an ad hoc power analysis, because of the lack of prior research on the relationship between resilience and narcissism. Therefore, we calculated power using the effects from current study. We obtained the following results: for all significant effects, the power was above 0.97. Sensitivity analysis indicated that we are able to detect effects r = .10 assuming power equal .80. The power was calculated with the GPower program version 3.1.9.4 (Erdfelder, Faul, & Buchner, 1996).

Three forms of resilience were correlated. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism were positively, yet weakly, correlated. Grandiose narcissism was positively correlated to ecological resilience and adaptive capacity but not to engineering resilience. Vulnerable narcissism was negatively correlated to all dimensions of resilience. Resilience was unrelated with sex and age. Men indicated higher levels of grandiose narcissism. Both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism was negatively related with age. To compare the strength of the correlations, z-tests for dependent samples were performed using an online calculator (Eid, Gollwitzer, & Schmitt, 2011). Results are presented in Table 2. We have found that grandiose narcissism was related (positively) more strongly with ecological resilience followed by adaptive capacity, and with weakest relation with engineering resilience. Vulnerable narcissism was related (negatively) more strongly with engineering resilience and adaptive capacity than ecological resilience.

Relationship between Grandiose Narcissism, Vulnerable Narcissism, and Resilience

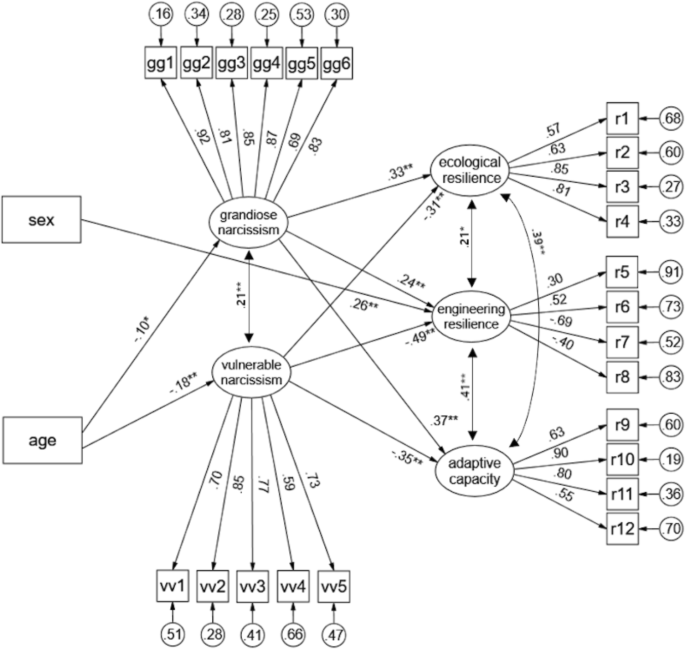

Basing on our hypotheses regarding relationship between two forms of narcissism and three dimensions of resilience we tested a Structural Equation Model using mPlus with Robust Maximum Likelihood estimation, and relied on common cut-off recommendations for good fit (Byrne, 1994): Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.90, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < 0.10.

We based our measurement model for vulnerable and grandiose narcissism on the parcels constituted by two up to three items (Matsunaga, 2008) and on single items for three correlated latent factors corresponding to three dimensions of resilience. We introduced participants’ age and sex as covariates. The model (Fig. 1) fit the data well (χ2[25] =789.71, p < .001, CFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.06 [.05; .06]; p < .008, SRMR = 0.06). We conducted the power analysis calculation which was equal to 1.00 (McCallum et al., 1996). Higher levels of grandiose narcissism was positively related with all dimensions of resilience, while higher levels of vulnerable narcissism was related with all dimensions of resilience negatively. There were no sex differences in the narcissism levels and two of three dimensions of resilience. Men indicated higher levels of engineering resilience than women. Younger participants indicated higher levels of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, while resilience was unrelated with age.

Discussion

In the current study we examined the relationships between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism and three-dimensional resilience. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism were weakly positively correlated to each other, despite that these are often assumed to be relatively orthogonal (see Krizan & Herlache, 2018 for discussion). This result could be caused by common method bias, but it also could be a result of the content the Narcissistic Grandiosity Scale, which not only refers to grandiose narcissistic traits, but also taps into antagonism (Weiss et al., 2019).

Grandiose narcissism was positively correlated to all dimensions of resilience. Ecological resilience and adaptive capacity had the strongest relation with grandiose narcissism. Both adaptive capacity and ecological resilience are responsible for preventing the individual from disturbances caused by changes in the environment (Maltby et al., 2015). Regression analyses detected suppression effect for engineering resilience, suggesting that this dimension is related uniquely to narcissistic grandiosity (after partialling out its shared variance with vulnerable narcissism). As grandiose narcissism is predominantly agentic (Grijalva & Zhang, 2016); it is therefore particularly relevant for agentic aspects of resilience, especially engineering resilience allowing for recovery after experiencing stressful events. Our findings suggest that grandiose narcissism is accompanied by a general capacity to adapt and being resistant to stressful events rather than to recover after experiencing stress. As adaptive capacity is positively related to openness to experience, probably grandiose narcissists perceive changes in the environment as less stressful.

On the other hand, vulnerable narcissism is negatively correlated to ecological resilience, engineering resilience, and adaptive capacity. As predicted, engineering resilience has the strongest relation to vulnerable narcissism. This result can be explained by the highest negative correlation being between engineering resilience and neuroticism (Maltby et al., 2015) which, in turn, is positively correlated with vulnerable narcissism (Miller et al., 2011). Vulnerable narcissism is considered as more passive than grandiose narcissism (Freis et al., 2015), which can be an explanation for the stronger negative correlation between vulnerable narcissism and engineering resilience than analogue correlations between the other dimensions of resilience and vulnerable narcissism. Therefore, it seems that vulnerable narcissists experience problems with a recovery after stressful events because of their lack of agency.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study is based on self-report data, which is a limitation, especially given that narcissistic individuals have a biased image of themselves (Gabriel et al., 1994). There is still a need for further research about narcissism and resilience not only on self-report data but also on behavioural or psychophysiological data, which can provide a better understanding of the relation of narcissism and resilience. Our research was conducted in the Polish culture, which could affect generalisation of the findings, as Poland is an European, affluent and moderately individualistic country (see Henrich et al., 2010). However, Polish cultural context offers an opportunity to extend former research by including the less-studied population of Central Europe, not so highly individualistic as English-speaking societies (Hofstede et al., 2010). Both narcissism and resilience were studied cross-culturally before; these results suggested that at least grandiose narcissism is present in individualistic and collectivistic countries (Foster et al., 2003), and the resilience model is also replicable across cultures, including Poland (Maltby et al., 2016). Preliminary studies suggest that Poles indicate rather lower levels of grandiose narcissism than other populations, at least regarding student samples (Jonason et al., 2020). On the other hand, it is impossible to state whether the resilience level is related to individualism-collectivism dimension, because of lack of measurement invariance between compared cultures (i.e., Poland, Japan, and the UK), allowing for reliable comparisons in the resilience levels (see Maltby et al., 2016).

Further studies could search for possible mechanisms involved in the link between narcissism and resilience. Grandiose narcissists could indicate higher levels of resilience because of its activity aspect, accompanied by higher self-confidence and self-esteem, therefore ecological resilience is the most important aspect of resilience among grandiose narcissists. Moreover, grandiose narcissists perceive less stress, while vulnerable narcissists perceive more stress (Papageorgiou et al., 2019). Our study suggests that people with higher levels of grandiose narcissism are more resilient mostly because they are more ready to accept changes and they indicate higher ability to be resistant to stressful events. However, their ability to recover after experiencing stress is a less important aspect of their resilience. Therefore, it is possible that people with higher levels of grandiose narcissism perceive the environment as more controllable than people with higher levels of vulnerable narcissism (Papageorgiou et al., 2019) what in turn result in their higher resilience.

Vulnerable narcissists seem to have lower levels of resilience mostly because of their higher frequency and intensity of experiencing negative events (see Miller et al., 2018), what is reflected with strongest negative relations with engineering resilience. Therefore, the most problematic aspect of their resilience is related to lower levels of agency and problems with recovery after experiencing stress rather than with the more general negative self-perception. However, these assumptions require further research.

Our findings provide some possible recommendations for clinical practice, pointing the different source of resilience among people with higher levels of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, respectively. Grandiose narcissists manifest greater belief in their capacity to deal with stressful events and they are more open to the changes in the environment. Such beliefs could increase their subjective well-being (Dufner et al., 2019; Papageorgiou et al., 2019). On the other hand, vulnerable narcissists indicate lower ability to recover after stressful events, therefore they could exaggerate the problems and react more strongly to negative situations. As a result, vulnerable narcissists require more professional help, encouraging them for active dealing with a problematic situation and lowering the levels of experienced stress by restoring the self-confidence.

Conclusions

Our findings supplement knowledge about functioning of people with higher levels of vulnerable and grandiose narcissism with respect to their ability to maintain equilibrium and a healthy state. People with higher levels of grandiose narcissism displayed higher levels of resilience, mostly through ecological resilience, which could be considered as active dimension and greater self-confidence, reflected in higher levels of adaptive capacity. Vulnerable and grandiose narcissism operate in the opposite way in regard to engineering resilience, as uniquely grandiose aspect of narcissism is associated with better recovery, while uniquely vulnerable aspect suppresses this positive effect of grandiose narcissism. Vulnerable narcissists displayed lower levels of resilience, mostly through emotional dysregulation (as expressed especially in lower levels of engineering resilience), which could explain their lower ability to manage stressful events and resulting lower subjective wellbeing. In addition, we used the adjectively-based measures of narcissism what allow for assessing both global levels of narcissism and fluctuations in this trait (Edershile & Wright, 2019). Therefore, possible replications of the current study could employ Experience Sampling Method (Edershile & Wright, 2019) to direct compare the global levels and fluctuations of narcissism in the context of resilience.

References

Brummelman E., Gürel Ç., Thomaes S., Sedikides C. (2018) What Separates narcissism from self-esteem? A social-cognitive perspective. In: Hermann A., Brunell A., Foster J. (eds) Handbook of Trait Narcissism. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_5.

Buyl, T., Boone, C., & Wade, J. B. (2017). CEO narcissism, risk-taking, and resilience: An empirical analysis in U.S. commercial banks. Journal of Management, 45(4), 1372–1400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317699521.

Byrne, B. M. (1994). Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Sage.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences, 13.6, 653–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(92)90236-I.

Crowe, M., Carter, N. T., Campbell, W. K., & Miller, J. D. (2016). Validation of the narcissistic grandiosity scale and creation of reduced item variants. Psychological Assessment, 28, 1550–1560. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000281.

Crowe, M. L., Edershile, E. A., Wright, A. G. C., Campbell, W. K., Lynam, D. R., & Miller, J. D. (2018). Development and validation of the narcissistic vulnerability scale: An adjective rating scale. Psychological Assessment, 30, 978–983. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000578.

Davydov, D. M., Stewart, R., Ritchie, K., & Chaudieu, I. (2010). Resilience and mental health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(5), 479–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.003.

Duffner, M., Gebauer, J. E., Sedikides, C., & Denissen, J. A. (2019). Self-enhancement and psychological adjustment: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 23(1), 48–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868318756467.

Edershile, E. A., Woods, W. C., Sharpe, B. M., Crowe, M. L., Miller, J. D., & Wright, A. G. C. (2019). A day in the life of Narcissus: Measuring narcissistic grandiosity and vulnerability in daily life. Psychological Assessment, 31(7), 913–924. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000717.

Eid, M., Gollwitzer, M., & Schmitt, M. (2011). Statistik und Forschungmethoden Lehrbuch [statistics and research methods textbook]. Weinheim, Germany: Beltz.

Erdfelder, E., Faul, F., & Buchner, A. (1996). Behavior research methods. Instruments, & Computers, 28, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03203630.

Folke, C., Carpenter, S. R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chapin, T., & Rockström, J. (2010). Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability. Ecology and Society, 15(4), 20 http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art20/.

Foster, J. D., & Trimm, R. F., IV. (2008). On being eager and uninhibited: Narcissism and approach-avoidance motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1004–1017. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208316688.

Foster, J. D., Campbell, W. K., & Twenge, J. M. (2003). Individual differences in narcissism: Inflated self-views across the lifespan and around the world. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 469–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00026-6.

Freis, S. D. (2018). The distinctiveness model of the narcissistic subtypes (DMNS): What binds and differentiates grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. In A. D. Hermann, A. B. Brunell, & J. D. Foster (Eds.), Handbook of trait narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies (pp. 37–46). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_4.

Freis, S. D., Brown, A. A., Carroll, P. J., & Arkin, R. M. (2015). Shame, rage, and unsuccessful motivated reasoning in vulnerable narcissism. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34(10), 877–895. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2015.34.10.877.

Frick, P. J., & Hare, R. D. (2001). Antisocial process screening device: APSD. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

Gabriel, M. T., Critelli, J. W., & Ee, J. S. (1994). Narcissistic illusions in self-evaluations of intelligence and attractiveness. Journal of Personality, 62, 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00798.x.

Grijalva, E., & Zhang, L. (2016). Narcissism and self-insight: A review and meta-analysis of narcissists’ self-enhancement tendencies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215611636.

Henrich, J., Heine, S., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature, 466, 29. https://doi.org/10.1038/466029a.

Hill, P. L., & Lapsley, D. K. (2011). Adaptive and maladaptive narcissism in adolescent development. In Narcissism and Machiavellianism in youth: Implications for the development of adaptive and maladaptive behavior (pp. 89–105). https://doi.org/10.1037/12352-005.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245.

Hyatt, Courtland S.., Sleep, Chelsea E.., Lamkin, Joanna, Maples-Keller, Jessica L.., Sedikides, Constantine, Campbell, W. Keith., et al. (2018). Narcissism and self-esteem: A nomological network analysis. PLOS ONE, 13, e0201088.

Jonason, P., Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M., Piotrowski, J., Sedikides, C., Campbell, W. K., (...), & Yagiyayev, I. (2020). Country-level correlates of the dark triad traits in 49 countries. Journal of Personality, advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12569, 88, 1252, 1267.

Kauten, R., Barry, C. T., & Leachman, L. (2013). Do perceived social stress and resilience influence the effects of psychopathy-linked narcissism and CU traits on adolescent aggression? Aggressive Behavior, 39(5), 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21483.

Krizan, Z., & Herlache, A. D. (2018). The narcissism spectrum model: A synthetic view of narcissistic personality. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868316685018.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1, 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130.

Maltby, J., Day, L., & Hall, S. (2015). Refining trait resilience: Identifying engineering, ecological, and adaptive facets from extant measures of resilience. PLoS One, 10(7), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131826.

Maltby, J., Day, L., Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M., Piotrowski, J., Hitokoto, H., Baran, T., & Flowe, H. D. (2016). An ecological systems model of trait resilience: Cross-cultural and clinical relevance. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.100.

Matsunaga, M. (2008). Item parceling in structural equation modeling: A primer. Communication Methods and Measures, 2, 260–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312450802458935.

Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Gaughan, E. T., Gentile, B., Maples, J., & Keith Campbell, W. (2011). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis. Journal of Personality, 79(5), 1013–1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00711.x.

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Hyatt, C. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2017). Controversies in narcissism. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 291–315. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045244.

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Vize, C., Crowe, M., Sleep, C., Maples-Keller, J. L., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Vulnerable narcissism is (mostly) a disorder of neuroticism. Journal of Personality, 86(2), 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12303.

Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12(4), 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1204_1.

Ng, H. K. S., Cheung, R. Y.-H., & Tam, K.-P. (2014). Unraveling the link between narcissism and psychological health: New evidence from coping flexibility. Personality and Individual Differences, 70, 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.06.006.

Papageorgiou, K. A., Gianniou, F.-M., Wilson, P., Moneta, G. B., Bilello, D., & Clough, P. J. (2019). The bright side of dark: Exploring the positive effect of narcissism on perceived stress through mental toughness. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.004.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452.

Rohmann, E., Brailovskaia, J., & Bierhoff, H. W. (2019). The framework of self-esteem: Narcissistic subtypes, positive/negative agency, and self-evaluation. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00431-6.

Rose, P. (2002). The happy and unhappy faces of narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(3), 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00162-3.

Samani, S., Jokar, B., & Sahragard, N. (2007). Effects of resilience on mental health and life satisfaction. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 13(3), 290–295 http://ijpcp.iums.ac.ir/article-1-275-en.html.

Sedikides, C.S. (2020). In search of Narcissus. Trends in Cognitive Science. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2020.10.010, 25, 67, 80.

Sedikides, C., Rudich, E. A., Gregg, A. P., Kumashiro, M., & Rusbult, C. (2004). Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy?: Self-esteem matters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 400–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.400.

Sękowski, M., Subramanian, Ł., Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M., & Rogoza, R. (2018, December). Polish adaptation of adjective scales for measuring narcissism: NVS (Narcissism Vulnerability Scale) and NGS (Narcissism Grandiosity Scale). Poster session presented at the Psychodebiuty IX, 2018, Polish conference, Jagiellonian University, Kraków.

Sturgeon, J. A., & Zautra, A. J. (2010). Resilience: A new paradigm for adaptation to chronic pain. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 14(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-010-0095-9.

Walker, B., Holling, C. S., Carpenter, S. R., & Kinzig, A. (2004). Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 9(2), 5 http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss2/art5/.

Weiss, B., Campbell, W. K., Lynam, D. R., & Miller, J. D. (2019). A trifurcated model of narcissism: On the pivotal role of trait antagonism. In J. Miller & D. Lynam (Eds.), The handbook of antagonism (pp. 221–235). Oxford: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-814627-9.00015-3.

Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.590.

Wu, Wenqing, Wang, Hongxin, Lee, Hsiu-Yu., Lin, Yu-Ting., & Guo, Feng. (2019). How machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism affect sustainable entrepreneurial orientation: The moderating effect of psychological resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 10.

Yun, S., & Min, S. (2018). The relationship narcissism, resilience, and youth activity competence in adolescents. Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development, 9(9), 800–806. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-5506.2018.01097.5.

Zuckerman, M., & O’Loughlin, R. E. (2009). Narcissism and well-being: A longitudinal perspective. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 957–972. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.594.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank John Maltby and Peter Jonason for commenting the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Polish National Science Centre (grant number 2017/26/E/HS6/00282).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures were approved by the institutional ethics board (KEiB – 10/2018). Informed consent was obtained prior to data collection from each participant. Data will be available as a part of the submission via osf link.

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The study was founded by Narodowe Centrum Nauki (2017/26/E/HS6/00282). Grant recipient: Magdalena Żemojtel-Piotrowska

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 24 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sękowski, M., Subramanian, Ł. & Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M. Are narcissists resilient? Examining grandiose and vulnerable narcissism in the context of a three-dimensional model of resilience. Curr Psychol 42, 2811–2819 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01577-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01577-y