Abstract

COVID-19 has been shown to detrimentally affect eating disorder symptoms, including increased dietary restriction and increased binge eating. However, research in this area is thus far limited. Additionally, as a result of the pandemic, many eating disorder treatments have converted to tele-health platforms, however, little is known about patient perceptions of this modality. The aim of the present, exploratory study was to qualitatively examine: (1) The impact of COVID-19 on binge eating spectrum disorder symptoms (2) Patient perceptions of tele-therapy, and (3) Ways to address COVID-19 in eating disorder treatment. Data were collected through one-on-one, semi-structured interviews (N = 11), conducted as part of a mid-program assessment for those undergoing individual, outpatient therapy for binge eating spectrum disorders. After thematic analysis, it was identified that patients reported both symptom deterioration and improvement during COVID-19. Factors surrounding social distancing and stay-at-home measures were found to both improve and worsen symptoms for different patients. Further, patients reported positive perceptions of tele-therapy, particularly appreciating the convenience of this modality. Finally, patients provided variable feedback on the incorporation of COVID-related concerns into their eating disorder treatment, with some participants wishing for this inclusion, and others viewing COVID-19 and their eating disorder as separate issues. Findings from the present study preliminarily identify ways in which binge eating spectrum disorder symptoms may have improved due to COVID-19 and indicate positive patient perceptions of tele-therapy. Our results may be used to inform the adaptation of future eating disorder treatment during COVID-19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown protocols to mitigate the spread of the virus have had a vast impact on mental and physical health. Initial reports from China suggest that between 20 and 50% of the population has experienced psychological concerns associated with the pandemic (Li et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). In a United States survey, approximately 40% of respondents endorsed at least one adverse mental health condition in response to COVID-19 (Czeisler et al., 2020). Increases in anxiety, depression, substance use, and disordered eating have all been shown in relation to the pandemic (Termorshuizen et al., 2020; Vindegaard & Benros, 2020), and the long-term effects on mental health are not yet known. At the time of the present study in August 2020, the United States reported an average COVID-19 hospitalization rate of 152 per 100,000 and a testing positivity rate of 6%, with almost 8% of all deaths in the country attributed to pneumonia, influenza, or COVID-19 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

A particular area of interest is the impact of COVID-19 on eating behaviors, physical activity, and other lifestyle factors. Even in the general population, individuals have been shown to engage in great levels of unhealthy eating, including increased consumption of comfort food, increased snacking, and decreased control over eating (Ammar et al., 2020; Di Renzo et al., 2020). In an Italian study, almost 50% of those surveyed perceived to have gained weight during lockdown (Di Renzo et al., 2020). Phillipou et al. (2020) found an increase in behaviors such as food restriction and binge eating in the general population, as well as increased restriction, binge eating, purging and exercise in those with eating disorders. These findings suggest that a large portion of the population are susceptible to changes in eating habits at this time, particularly those with eating disorders.

Preliminary findings regarding the impact of COVID-19 on eating disorders mostly suggest a deterioration of symptoms, with some studies indicating the presence of symptom improvement (Baenas et al., 2020; Branley-Bell & Talbot, 2020; Castellini et al., 2020; Fernández-Aranda et al., 2020; Phillipou et al., 2020; Schlegl, Maier, Meule, & Voderholzer, 2020; Termorshuizen et al., 2020), however the research available thus far is nascent. In a large sample of American and Danish participants (N = 1021), individuals with anorexia reported increased restriction, while those with binge eating and bulimia reported increased binge eating (Termorshuizen et al., 2020). Additionally, 70% of those with anorexia nervosa have reported an increase in symptoms such as eating, shape, and weight concerns (Schlegl et al., 2020).

Eating disorder symptom improvement has been observed in a minority of cases (Branley-Bell & Talbot, 2020; Brown et al., 2020; Schlegl et al., 2020; Termorshuizen et al., 2020). In these studies, anywhere between 2% to 25% of patients cited positive outcomes associated with the pandemic (Branley-Bell & Talbot, 2020; Schlegl et al., 2020). Cited reasons for improvement of symptoms include increased social support, positive changes to daily routine and structure, and increased motivation for recovery (Branley-Bell & Talbot, 2020; Brown et al., 2020; Schlegl et al., 2020; Termorshuizen et al., 2020). The majority of participants in these studies at a diagnosis of anorexia nervous, or their specific eating disorder diagnosis was not known. To date, little is currently known about the effects of COVID-19 on binge eating spectrum disorders, nor whether COVID-19 has contributed to eating disorder symptom improvement for this population.

Consistent with the literature reviewed above, there is the possibility that some individuals with binge eating may have experienced alterations to their food environment and/or stressors that could reduce binge eating, although the literature addressing this is presently lacking. For example, having fewer opportunities for social eating, more control over their food environment, reduced access to trigger foods, and more flexibility in daily scheduling may lead to less overall stress and reduced binge eating for some. However, these factors have yet to be examined as potential contributors to binge eating symptom amelioration specifically at this time. Rather, the emphasis has been on studying anorexia or transdiagnostic eating disorder samples, with no specificity as to the examination of binge eating spectrum disorders.

As a result of the pandemic, much mental health treatment, including eating disorder treatment, has migrated to a tele-health platform. Tele-health interventions for eating disorders have been shown in past trials to be as effective as their face-to-face counterparts (Mitchell et al., 2008; Shingleton, Richards, & Thompson-Brenner, 2013), however the transition to tele-health delivery during the pandemic has yielded mixed results. While access to in-person eating disorder treatment has been shown to decrease by 37% in one study, tele-therapy was used by 26% of the patients surveyed (Schlegl et al., 2020). Patient and provider perceptions of this transition are thus far mixed. Qualitative findings from pilot study found that patients missed the structure of in-person treatment and weekly weigh-ins (Fernández-Aranda et al., 2020). In another qualitative exploration of patient perceptions of group therapy, while the majority failed to cite dislikes of virtual groups, the general consensus was a preference for connectedness of in-person groups (Datta, Derenne, Sanders, & Lock, 2020). The research thus far regarding eating disorder patient perceptions of tele-therapy has been limited to quantitative analysis of the frequency of tele-therapy use or informal assessments of patient perceptions of group therapy. Thus, more research is needed to comprehensively, qualitatively understand the benefits and limitations of individual tele-therapy and to identify patient preferences regarding this modality.

Finally, based on the aforementioned effects of COVID-19 on eating disorder symptoms, the long-term duration of the pandemic, and the increased prevalence of tele-therapy as a key treatment modality moving forward, it would be beneficial to better understand how COVID-related concerns can be addressed in pre-existing treatments for eating disorders. Given the ways in which COVID-19 has been linked to eating disorder symptom deterioration, it may be useful to explicitly incorporate the context of the pandemic into treatment in order to better problem solve and adapt to these barriers.

Based on these previous findings, the aim of the present, exploratory study was to qualitatively examine: (1) The impact of COVID-19 on binge eating spectrum disorder symptoms (2) Patient perceptions of tele-therapy, and (3) Ways to address COVID-19 in eating disorder treatment. Data were collected through one-on-one, semi-structured interviews, conducted as part of a mid-program assessment for those undergoing individual outpatient therapy for binge eating spectrum disorders.

Methods

The study is reported in line with COREQ (COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research; Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007).

Participants

Participants for the study were individuals undergoing a pilot outpatient individual therapy treatment program for binge eating spectrum disorders (N = 12). All individuals who finished the pilot program also completed the study interview. One participant was excluded because of technical concerns that inhibited the audio recording of their interview (final sample, N = 11). Inclusion/exclusion criteria can be found in the protocol paper for the RCT (Juarascio et al., 2020). Demographic information can be found in Table 1.

Procedure

The study was approved by the university’s research ethics board. Interviews were conducted from August 3–27, 2020, which corresponded with when participants completed their mid-program assessments. The majority of participants resided in the Northeastern United States. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, all recruitment and program participation was conducted virtually.

Individual, semi-structured interviews were conducted during the treatment’s mid-program assessment via HIPPA Compliant Zoom. The mid-program assessment was held after session 8 of the 16-session program. Full methodology for the RCT can be found in its protocol paper (Juarascio et al., 2020). Participants were asked a series of questions pertaining to the perceived impact of COVID-19 on their eating disorder symptoms prior to starting treatment, their experience with tele-therapy, and their feedback on adapting treatment to address COVID-related concerns (see Table 2 for interview questions). Prior to commencing the interview, participants were informed that they were to be asked questions about their evaluation of the treatment program. The interviews were conducted by female research coordinators with a Bachelor’s degree who were trained in the implementation of the interview battery (e.g., had completed a minimum of 10 supervised clinical interviews and who had achieved satisfactory inter-rater reliability on diagnoses) and had no pre-existing relationship with participants. Interviews were audio-recorded for later transcription. On average, the portion of the interview focused on COVID-19 took approximately 10 to 15 min to complete. Participants were compensated with a $75 Visa gift card at the end of the interview.

Data Analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) procedure for thematic analysis in psychological research. A data-driven, inductive approach was used to derive themes from the data. As per Braun and Clarke’s (2006) procedure, interview data was transcribed and semantically coded into meaningful units. Next, these codings were organized into proposed themes and subthemes. These themes were subsequently reviewed and edited iteratively by all three authors until 100% consensus was reached. Table 3 outlines the coding tree. Data saturation was achieved after nine interviews, at which point no new themes were identified from participant interview data. This is consistent with findings from Guest, Bunce, and Johnson (2006) that data saturation may occur after as few as six interviews.

Results

Themes are described below, including the number of participants who contributed to each theme. Because of the small sample size, themes were identified through commonalities in responses across participants (i.e., responses from a single participant were not used to establish idiosyncratic themes).

Impact of COVID-19 on Eating Disorder Symptoms

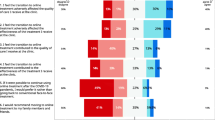

Regarding the impact of COVID-19 on eating disorder symptoms pre-treatment, four themes were derived from the interview data including: (T1) Variability in the improvement or exacerbation of symptoms due to COVID-19 (n = 11), (T2) Changes in the physical environment were associated with symptom improvement (n = 5), (T3) Social implications of COVID-19 (i.e., social distancing, isolation) were associated with both symptom improvement and deterioration (n = 7), and (T4) Greater overall stress/anxiety levels leads to more binge episodes (i.e., symptom deterioration) (n = 7).

First, different participants reported their eating disorder symptoms as having improved or worsened as a result of COVID-19 (T1). While about half of the sample reported a worsening of symptoms (n = 5), the remaining half reported improvement (n = 3), no impact (n = 2), or both improvement and deterioration (n = 1).

For those who reported symptom improvements, greater control over their physical environment was cited as the primary reason for these improvements (T2). Some participants reported having reduced access to trigger foods and/or triggering situations due to confinement at home, thus leading to fewer binges and less overeating. Others cited that it was easier to schedule and plan regular meals and snacks at home, and thus avoid dietary restraint throughout the day. Regular eating and the avoidance of excessive hunger was reported to help in avoiding binge eating.

“I’m typically at home so it has gotten better. I have access to meals and snacks at home and don’t go long periods without eating.” (504)

Social distancing, isolation, and other social implications of COVID-19 were found to either improve or worsen symptoms (T3). Having less privacy to engage in binge episodes secretively and less social commitments associated with food and eating were cited to improve symptoms (n = 3). Conversely, increased isolation, eating due to loneliness, and a less structured daily routine with regard to eating and exercise were reported to contribute to unhealthy eating habits and the worsening of eating disorder symptoms (n = 4).

“My symptoms have probably gotten better because I am home and can’t go anywhere. Before my binge episodes were on the road and I was by myself. The fact that I am physically constrained and don’t have access to what I had before helps. I don’t go out much, not by myself. I am with my kids and family, so I don’t have privacy and am very conscious of that.” (513)

Additionally, as a result of being at home more often, some participants described having more time to be preoccupied with food and eating and that this led to a worsening of their symptoms. This was reflective of less occupation and lack of engagement with other activities (i.e., fewer distractions) facilitating greater preoccupation with food. There was also a reported impact of COVID-19 on weight and shape overconcern due to stay-at-home measures. One participant cited having greater access to her scale, which led to more weighing and more distress about body image.

“Everything is dramatically worse because of being home all the time. I have constant access to all of my food and my scale and everything to evaluate where I’m at and to facilitate eating.” (519)

The most frequently cited factor associated with symptom deterioration was the greater overall life stress reported as a result of COVID-19 and subsequent use of food to regulate negative emotions (T4). Participants reported being more on-edge due to COVID-related restrictions and fear about their exposure to the virus, as well as more specific stressors such as family, finances, and job insecurity. A lack of coping skills to address these stressors was cited as a reason for using food to self-regulate and thus engage in binge eating.

“If there’s an anxiety component, like exposure to disease or job concerns, it has an effect on me and triggers me, which means more binges.” (516)

Perceptions of Tele-Therapy

Regarding participant’s perceptions of tele-therapy, five themes were derived including: (T1) Tele-therapy was positively perceived by the majority of participants (n = 9), (T2) Tele-therapy is convenient and facilitates attendance and engagement (n = 8), (T3) Tele-therapy makes treatment accessible for those who would be otherwise unable to attend (n = 5), (T4) Tele-therapy is perceived as more impersonal than in-person therapy (n = 4), and (T5) Tele-therapy may be hindered by logistical or technical concerns (n = 4).

Overall, 9 out of 11 participants reported that they had a positive experience with tele-therapy (T1). Several participants cited tele-therapy as being a suitable alternative, with comparable efficacy, to in-person sessions. Increased convenience was cited as the main benefit of tele-therapy (T2). Participants reported that reduced travel time and the removal of other logistical barriers such as finding parking and taking time off work, made at-home sessions easier to attend. They also discussed that the increased flexibility of appointments and scheduling made it easier to incorporate therapy into their day. With the reduction of these logistical barriers, participants reported experiencing less anxiety related to timeliness and attendance, citing that this helped to make therapy a less stressful experience. Finally, participants endorsed that it was easier to attend and be present to participate during sessions because these aforementioned barriers to convenience were lifted.

“I like the flexibility. Trying to do it {therapy} within a workday would be more stressful. It’s easier for me to be working and take a Zoom call, versus working and have to get up and get to wherever the in-person session would be. It’s pretty stress free to attend and be present in sessions” (504)

Similar but distinct from the theme of convenience, several participants reported that tele-therapy made treatment more accessible in cases where they otherwise would not have been able to attend (T3). Specifically, this was endorsed by those who lived further from the treatment center where therapy would usually be offered in-person. One participant also noted that increased accessibility may also facilitate attendance, for example explaining that they were less likely to cancel sessions at-home vs. in-person because of the accessibility of the online platform.

“I live outside of Philadelphia, so virtual therapy is the only possible way.” (506)

Tele-therapy was perceived as more impersonal than in-person therapy by a small number (n = 4) of participants (T4), however there was great variation in whether or not this was viewed as a positive quality. For one participant, the impersonal nature was cited as a benefit that mitigated concerns regarding the anxiety associated with opening up to a therapist in-person. This individual even described tele-therapy as being preferred to in-person therapy for this reason. For others rather, tele-therapy was viewed as a barrier to connection and this lack of connection was cited as a reason for preferring in-person to tele-therapy, as well as the feeling that tele-therapy had reduced efficacy (n = 2). Finally, one participant expressed both of these perspectives and was ambivalent regarding whether or not the impersonal nature of tele-therapy helped or hindered her openness to discuss sensitive topics.

“Is it possible that I would have been more open or vulnerable if I was outside my comfort zone? Maybe, maybe not. I haven’t felt like the fact that it was Zoom versus not is an interference.” (515)

Finally, a small number of participants (n = 4) reported that tele-therapy may be hindered by logistical or technical concerns (T5). These concerns related to technology or Internet issues, as well as not having the privacy to engage in tele-therapy at home.

“I don’t feel like there’s a great space in my home to do it which is a bit challenging. Options about other places to go are so limited right now so I don’t love that.” (519)

Addressing COVID-19 in the Present Treatment

Three themes were identified with regard to addressing COVID-19 in the present treatment including: (T1) Consistent or increased motivation to participate in treatment (n = 10), (T2) Variable desire for COVID-related concerns to be addressed in ED treatment (n = 11), and (T3) Conflicts between COVID-19 and treatment (n = 2).

Participants were equally divided in their views on whether COVID-19 changed or increased motivation to be in treatment (T1), with half of the sample reporting no change in motivation (n = 5) and half reporting increased motivation (n = 5) (of note, one individual did not discuss motivation for treatment during the interview and thus is not included in this theme). No participants cited reduced motivation as a result of COVID-related factors. Increased motivation was attributed to aforementioned logistical considerations such as increased convenience and accessibility of tele-therapy. Participants described the ease of tele-therapy as a factor that contributed to their willingness to engage. COVID-19 itself was also cited as a factor that increased motivation to participate because of exacerbated eating disorder symptoms and overweight being a risk factor for COVID-19 complications. One participant even suggested building these factors into future treatment protocol to use them as motivators to help others change their behavior.

“The fact that if I were at a healthier weight, my risk factors for this {COVID} would be better. That is a motivation because I think we are going to be living with this for a while. It was easier when we were quarantined – now we are more out and I am at more risk –I’m more concerned to make myself as healthy as possible so I can withstand anything that happens.” (515)

While some participants endorsed the desire for COVID-related concerns to be addressed in the context of eating disorder treatment (n = 6), others did not (n = 5), and there was large variability in this domain (T2). For those who opposed this, the challenges of COVID-19 were viewed as separate and distinct concerns outside of treatment for the eating disorder, with some participants even citing that they did not want to use COVID-19 as an “excuse” to avoid making changes. Others however, reported a desire for therapeutic skills that generalize beyond their eating disorder and could address numerous COVID-related concerns such as stress reduction, addressing isolation, loneliness, and building structure. Notably, those who reported worsened eating disorder symptoms as a result of COVID-19 were more likely to cite the desire to incorporate COVID-concerns into treatment.

“I think if my skillset gets better overall it will help me with COVID. It’s stress but also loneliness and alienation, and the political climate is so abysmal. If you’re going to binge eat, you’re going to binge eat because the world feels like it is going to blow up. I’m hoping to use coping skills beyond eating – the world has gotten very stressful – it’s almost just about life skills at this point.” (513)

Finally, while not frequently cited, some participants endorsed conflicts between COVID-19 and treatment (n = 2). Specifically, one participant cited difficulties practicing skills learned in treatment at the present time, as well as seeing applicability of skills after COVID, due to contextual differences. Another endorsed hopelessness that nothing could be done to address concerns related to COVID-19 (e.g., no way to change isolation that comes from social distancing). This participant held the concrete stance that COVID-19 could not be addressed in treatment because treatment could not do anything to change the circumstances surrounding COVID.

“I’m not being exposed to as many temptations since I’m at home and able to control my food environment, so that has been a really big help. On the flip side, I’m not able to really practice some of the skills from therapy, particularly once the pandemic is over.” (503)

Discussion

Findings from the present study provide preliminary, qualitative insight on three areas related to binge eating spectrum disorders, COVID-19, and tele-therapy, specifically: (1) The impact of COVID-19 on binge eating symptoms, (2) Patient perceptions of tele-therapy, and (3) Ways in which to address COVID-19 in eating disorder treatment.

Regarding the effect of COVID-19 on binge eating symptoms, participants cited a variety of examples in which their symptoms both improved and worsened in relation to the pandemic. While much of the previous literature has emphasized symptom deterioration (e.g., Baenas et al., 2020; Branley-Bell & Talbot, 2020; Castellini et al., 2020; Fernández-Aranda et al., 2020; Phillipou et al., 2020; Schlegl et al., 2020; Termorshuizen et al., 2020), we identified factors that may ameliorate binge eating symptoms, namely having greater control over the food environment and social implications of the pandemic contributing to more structure around food and eating. This is consistent with findings that suggest that changes in living situation due to COVID-19 are associated with symptom amelioration (Branley-Bell & Talbot, 2020; Schlegl et al., 2020; Termorshuizen et al., 2020). For example, for many participants in our study, being locked down at home was cited as a factor that helped to facilitate healthier food choices and reduced access to trigger foods. Additionally, reduced exposure to situations that may have previously triggered binge eating (e.g., work, social eating engagements) was reported as a reason for symptom improvement. Notably, factors such as isolation and social distancing had variable impact on binge eating symptoms, with some participants endorsing that pandemic-related restrictions on their socialization have had a positive effect on their eating, while others reported the contrary, citing associated loneliness and lack of structure as reasons for increased binge eating. Future research could examine patient characteristics that contribute to these differing responses to social distancing and stay-at-home measures, such as whether or not they reside alone, or the quality of their virtual social network. Despite two of our participants meeting criteria for bulimia nervosa, effects of the pandemic on compensatory behaviors were not mentioned by these individuals. Further research could examine how COVID-related factors may impact compensatory behaviors in those with eating disorders.

Further, the patients in our study reported that their motivation to pursue treatment for their eating disorder was not negatively impacted by COVID-19. While half of the sample reported no change in motivation due to the pandemic, the remaining half reported that the pandemic increased their motivation to engage with treatment. Reasons cited for this motivation included the convenience of tele-therapy, as well as concerns related to eating disorder symptoms and being at greater risk of contracting the virus. These findings are consistent with those from Brown et al. (2020), who identified that many patients displayed an increased drive for recovery in response to the stressors experienced during COVID-19. During treatment, high levels of motivation can be harnessed to encourage behavior change and help patients achieve their recovery goals. However, it should be noted that our sample was treatment seeking, which may have skewed results pertaining to the high levels of motivation endorsed to pursue therapy. Patient motivation should be assessed from treatment onset to tailor program goals to the individual.

With regard to patient perceptions of tele-therapy, the majority of participants cited having a positive experience that was akin to, if not preferred to, in-person therapy. These findings are also inconsistent with the limited literature that exists on this topic, in which patients were found to generally prefer in-person therapy to tele-therapy (Datta et al., 2020; Fernández-Aranda et al., 2020), although in Datta et al. (2020), these preferences were cited in the context of an inpatient sample. In our study, tele-therapy was viewed positively in large part due to the convenience and accessibility of this modality of therapy. Notably, all patients had begun treatment during COVID-19 and thus were only exposed to tele-therapy. Therefore, perceptions may differ for those who are accustomed to in-person therapy prior to beginning tele-therapy. Interestingly, aspects of tele-therapy that were described positively by some participants were viewed as detriments by others. Specifically, the more impersonal nature of tele-therapy was viewed as more of a benefit for those who reported that their anxiety and fear of judgment would otherwise be a barrier to pursuing in-person therapy. Conversely, others disliked the impersonality of tele-therapy compared to the connectedness of being with a therapist in-person. It may be that for patients who are more anxious and/or avoidant, tele-therapy is a modality that facilitates their willingness to attend treatment because it is less confronting, however more research is needed to better identify for whom tele-therapy is best suited. Given that tele-therapy allows patients to see themselves on the screen, one thing that remains unknown based on the findings of the present study is whether or not this may increase self-focus or social comparisons during therapy. Future research could explore whether or not this is experienced aversively by those with eating disorders, particularly in potentially exacerbating body image concerns.

Finally, participants in the present study were divided in their opinions on the incorporation of COVID-related content into their eating disorder treatment. Strikingly, approximately half of our sample did not wish or expect for COVID-related factors or concerns to be addressed in eating disorder treatment. For this subsample, COVID-19 and eating disorder symptoms were cited as distinct and separate issues, or patients held the belief that therapy ultimately could not change distressing, situational factors surrounding COVID-19 and thus the topic did not warrant discussion. For others, there was a strong desire to incorporate general life skills into the treatment protocol to address concerns specific to COVID-19. For example, many participants requested problem solving and planning tools, as well as general stress reduction to be incorporated into the treatment protocol beyond eating-specific concerns. Notably, those who suggested these additions were more likely to endorse that COVID-19 had worsened their eating disorder symptoms, which likely influenced their desire for COVID-19 related concerns to be more specifically addressed in treatment. Conversely, those who reported no impact of COVID-19 on their eating disorder symptoms were less likely to request that COVID-19 related content be integrated into treatment. These findings point to the importance of adapting and personalizing treatment to the individual, as responses to the pandemic are varied and some patients may require more COVID-19-related coping skills than others.

Findings from the present study have preliminary implications for the treatment of binge eating spectrum disorders during the pandemic. First, it is important to assess for individual differences in response to COVID-19 and the impact the pandemic has had on eating disorder symptoms. For those who report symptom deterioration, emphasis should be placed on addressing barriers to recovery that may be related to COVID-19. In particular, information can be drawn from those who have experienced improvements in their symptoms to better establish conditions for recovery for those who are struggling (e.g., increasing daily structure, drawing on social supports, etc.). Conversely, for those who report symptom amelioration, it may be useful to place greater emphasis on the maintenance of these improvements over time (i.e., focusing on the generalizability of behavior change following the pandemic). Second, patient feedback from the present study points to the need for the incorporation of broader stress management skills into eating disorder treatment to better address COVID-related stressors. These skills may be used as an add-on to treatment, particularly for patients who report a lack of adequate coping skills for pandemic-related factors such as anxiety, loneliness, and lack of structure.

Limitations

Limitations of the present study include a small sample size, which was predominantly female and Caucasian, thus limiting the generalizability to other races, ethnicities, and genders. Further, the majority of patients had a diagnosis of BED so findings may not be applicable across different eating disorders. Additionally, although patients were asked to report on the impacts of COVID-19 on their eating disorder symptoms pre-treatment, these perceptions were assessed at a mid-treatment assessment and thus their recall may have been different if asked in advance of starting treatment. Finally, while data saturation was achieved in nine interviews, due to the small sample size it is not known whether or not more themes would have been identified if a larger number of interviews had been conducted.

Conclusion

The present, exploratory study found a varied effect of COVID-19 on binge eating spectrum disorders, generally positive patient perceptions of tele-therapy, and mixed perspectives on the incorporation of COVID-related factors into eating disorder treatment. While future research with larger samples is needed to better understand what patient characteristics may contribute to these findings, our study has clinical implications for the treatment of binge eating and other eating disorders during COVID-19. Namely, taking an individualized approach to adapt treatment to various presenting problems at this time is necessary to ensure that therapy addresses concerns relevant to each patient. Although this is always important in a therapeutic context, it may be even more significant at this time given the variability in patient responses to COVID-19. Results from the present study may be used to inform the adaptation of future treatment for binge eating spectrum disorders during COVID-19.

What Is Already Known on this Subject?

Preliminary research on the relationship between COVID-19 and eating disorder symptoms has identified both symptom amelioration and deterioration, but has highlighted symptom deterioration. The majority of this research has been conducted with individuals with anorexia nervosa or non-specific eating disorder diagnoses.

What this Study Adds?

The present study provides greater insight into the impact of COVID-19 on eating disorder symptoms in those with binge eating spectrum disorders. It also highlights patient recommendations of how COVID-related factors could be incorporated into eating disorder treatment moving forward.

Data Availability

Data is available upon request from the authors.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Ammar, A., Brach, M., Trabelsi, K., Chtourou, H., Boukhris, O., Masmoudi, L., Bouaziz, B., Bentlage, E., How, D., Ahmed, M., Müller, P., Müller, N., Aloui, A., Hammouda, O., Paineiras-Domingos, L. L., Braakman-Jansen, A., Wrede, C., Bastoni, S., Pernambuco, C. S., Mataruna, L., … Hoekelmann, A. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behavior and physical activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients, 12(6), 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061583.

Baenas, I., Caravaca-Sanz, E., Granero, R., Sánchez, I., Riesco, N., Testa, G., Vintró-Alcaraz, C., Treasure, J., Jiménez-Murcia, S., & Fernández-Aranda, F. (2020). COVID-19 and eating disorders during confinement: Analysis of factors associated with resilience and aggravation of symptoms. European Eating Disorders Review, 28, 855–863. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2771.

Branley-Bell, D., & Talbot, C. V. (2020). Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and UK lockdown on individuals with experience of eating disorders. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8, 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00319-y.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Brown, S., Opitz, M. C., Peebles, A. I., Sharpe, H., Duffy, F., & Newman, E. (2020). A qualitative exploration of the impact of COVID-19 on individuals with eating disorders in the UK. Appetite, 156, 104977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104977.

Castellini, G., Cassioli, E., Rossi, E., Innocenti, M., Gironi, V., Sanfilippo, G., Felciai, F., Monteleone, A. M., & Ricca, V. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 epidemic on eating disorders: A longitudinal observation of pre versus post psychopathological features in a sample of patients with eating disorders and a group of healthy controls. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53, 1855–1862. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23368.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). COVIDView summary ending on August 15, 2020. Retrieved February 05, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covidview/past-reports/08212020.html.

Czeisler, M. É., Lane, R. I., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njai, R., Weaver, M. D., Robbins, R., Facer-Childs, E. R., Barger, L. K., Czeisler, C. A., Howard, M. E., & Rajaratnam, S. (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(32), 1049–1057. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1.

Datta, N., Derenne, J., Sanders, M., & Lock, J. D. (2020). Telehealth transition in a comprehensive care unit for eating disorders: Challenges and long-term benefits. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53, 1774–1779. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23348.

Di Renzo, L., Gualtieri, P., Cinelli, G., Bigioni, G., Soldati, L., Attinà, A., Bianco, F. F., Caparello, G., Camodeca, V., Carrano, E., Ferraro, S., Giannattasio, S., Leggeri, C., Rampello, T., Lo Presti, L., Tarsitano, M. G., & De Lorenzo, A. (2020). Psychological aspects and eating habits during COVID-19 home confinement: Results of EHLC-COVID-19 Italian online survey. Nutrients, 12(7), 2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12072152.

Di Renzo, L., Gualtieri, P., Pivari, F., Soldati, L., Attinà, A., Cinelli, G., Leggeri, C., Caparello, G., Barrea, L., Scerbo, F., Esposito, E., & De Lorenzo, A. (2020). Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. Journal of Translational Medicine, 18(1), 229. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5.

Fernández-Aranda, F., Casas, M., Claes, L., Bryan, D. C., Favaro, A., Granero, R., Gudiol, C., Jiménez-Murcia, S., Karwautz, A., Le Grange, D., Menchón, J. M., Tchanturia, K., & Treasure, J. (2020). COVID-19 and implications for eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 28(3), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2738.

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903.

Juarascio, A. S., Felonis, C. R., Manasse, S. M., Srivastava, P., Boyajian, L., Forman, E. M., & Zhang, F. (2020). The project COMPASS protocol: Optimizing mindfulness and acceptance-based behavioral treatment for binge-eating spectrum disorders. The International Journal of Eating Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23426.

Li, J., Yang, Z., Qiu, H., Wang, Y., Jian, L., Ji, J., & Li, K. (2020). Anxiety and depression among general population in China at the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic. World Psychiatry, 19(2), 249–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20758.

Mitchell, J. E., Crosby, R. D., Wonderlich, S. A., Crow, S., Lancaster, K., Simonich, H., Swan-Kremeier, L., Lysne, C., & Myers, T. C. (2008). A randomized trial comparing the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa delivered via telemedicine versus face-to-face. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(5), 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.004.

Phillipou, A., Meyer, D., Neill, E., Tan, E. J., Toh, W. L., van Rheenen, T. E., & Rossell, S. L. (2020). Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: Initial results from the COLLATE project. The International Journal of Eating Disorders., 53, 1158–1165. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23317.

Schlegl, S., Maier, J., Meule, A., & Voderholzer, U. (2020). Eating disorders in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from an online survey of patients with anorexia nervosa. The International Journal of Eating Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23374.

Shingleton, R. M., Richards, L. K., & Thompson-Brenner, H. (2013). Using technology within the treatment of eating disorders: A clinical practice review. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 50(4), 576–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031815.

Termorshuizen, J. D., Watson, H. J., Thornton, L. M., Borg, S., Flatt, R. E., MacDermod, C. M., Harper, L. E., van Furth, E. F., Peat, C. M., & Bulik, C. M. (2020). Early impact of COVID-19 on individuals with eating disorders: A survey of ~1000 individuals in the United States and the Netherlands. medRxiv : The Preprint Server for Health Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.28.20116301.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357.

Vindegaard, N., & Benros, M. E. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, S0889-1591(20)30954-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048.

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729.

Funding

This study was funded by The National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH122392).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frayn, M., Fojtu, C. & Juarascio, A. COVID-19 and binge eating: Patient perceptions of eating disorder symptoms, tele-therapy, and treatment implications. Curr Psychol 40, 6249–6258 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01494-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01494-0