Abstract

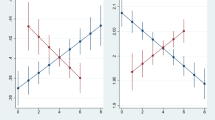

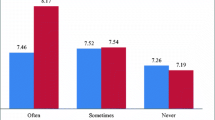

The relation between religiosity and generosity is a well explored topic in the literature, however almost no existing study systematically examines the behavioral route through which religiosity influences generosity. This paper proposes a model to systematically study the inter relation between religiosity of the donor and her generosity and hence attempts to fill an important gap in the existing literature pertinent to the religious studies. The behavioral model incorporates religiosity of the donor measured by frequency of prayers in her utility function and predicts a positive relation between religiosity and generosity. The predictions of the model are tested by applying tobit maximum likelihood regressions on real donations data acquired from two controlled lab experiments performed in the United States (Christian majority country; observations = 165) and Pakistan (Muslim majority country; observations = 75). The data from both lab experiments supports the predictions of the behavioral model; ceteris paribus, subjects in the United States who regularly attend religious service donate $0.76 more compared to non-regular attenders, while subjects in Pakistan offering on average four (five) daily prayers donate 31.26 (57.14) rupees more than subjects offering only one prayer a day. The paper extends our understanding by identifying a possible route through which religiosity can influence generosity. Such an understanding can be very useful when designing a mechanism to solicit donations from the religious people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data used in this study are acquired from the already published papers. The data set is provided as supplemental materials.

Notes

Donations, generosity and giving mentioned in this paper refer to the money given to others, usually a charity organization or a needy person without expecting anything in return and without any apparent material motive (Vesterlund, 2016). These types of donations are different from those induced by the motives of tax deductions.

National Philanthropic Trust. Source: https://www.nptrust.org/philanthropic-resources/charitable-giving-statistics/

Source: Connecting to Give: Faith Communities. http://jumpstartlabs.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ConnectedToGive3_FaithCommunities_Jumpstart2014_v1.3.pdf

Source: Philanthropy Daily. https://www.philanthropydaily.com/religious-philanthropy-faith/

Source: Coleman, A. (2017). Finance and Religion. Published by Lendedu.https://lendedu.com/blog/finance-and-religion/

Source: Connecting to Give: Faith Communities. http://jumpstartlabs.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ConnectedToGive3_FaithCommunities_Jumpstart2014_v1.3.pdf

Studies in the existing literature (for example: Greenway, Schnitker, & Shepherd, 2018) have already examined the relation between prayers and donations. However, current study offers a formal model to further extend understanding about the interaction of religiosity and generosity from a behavioral perspective.

The behavioral model reported in this paper is a modified version of the model that was a part of the author’s PhD thesis submitted to the Graduate School of Economics of Waseda University.

The authors report 10% subjects donate all endowment to a charity in a dictator game experiment.

The authors’ report 36% subjects donate all endowment in a dictator game experiment.

There are two types of charitable donations in Islam: ‘Zakat’ is a compulsory donation (2.5% of the income) while “Sadaqah” is a voluntary donation. Both types of donations can lead to a warm glow dependent on the religious satisfaction. Source: https://www.muslimaid.org/media-centre/blog/charity-in-islam/

For more details on the importance of charity in Islam please see the source: https://www.zakat.org/en/giving-charity-secret-publicly/

For more details on the importance of charity in Christianity please see: Charity and Christianity. New Statesman.

https://www.newstatesman.com/blogs/the-faith-column/2009/04/charity-love-god-christians

In a typical dictator game, one player acting as a dictator decides the distribution of a monetary endowment while the other player (which can be a charity) plays a passive role (Forsythe, Horowitz, Savin, & Sefton, 1994; Kahneman, Knetsch, & Thaler, 1986). The amount shared by the dictator is treated as a proxy for generosity.

I am thankful to Professor Eckel & Professor Grossman for sharing their experimental data.

A profound issue with survey studies is over-reporting the charitable donations (Sablosky, 2014). To avoid this confounding effect, the current paper relies on the experimental data reporting real money donations.

Source: PEW Research Center. https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/

Source: Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. http://www.pbs.gov.pk/sites/default/files//tables/POPULATION%20BY%20RELIGION.pdf

Under the single-blind procedure, the experimenter knows the decisions of the experimental subjects while under the double-blind procedure, the decisions are completely anonymous.

Studies also report a positive relation between religious activities and donations to religious organizations, however those studies are not considered here because such donations can be confounded by the religious orientation of the recipient organization.

The religiosity can also be measured by the introspective analysis of the religious beliefs, thoughts and feelings (Putnam & Campbell, 2010; Umer, 2020). However, as introspective analysis is subjective, its importance can be heterogenous across individuals and therefore makes it difficult to compare religiosity across subjects. Therefore, studies relying on the introspective method are not used in this paper.

The results from the data pooled for all treatments still shows a positive and significant effect of religiosity on generosity. For more details, please the regression output reported in Table 5 by Eckel and Grossman (2003).

Source: PEW Research Center. https://www.pewforum.org/2018/06/13/why-do-levels-of-religious-observance-vary-by-age-and-country/

References

Ahmed, A. M. (2009). Are religious people more prosocial? A quasi-experimental study with madrasah pupils in a rural community in India. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 48(2), 368–374.

Anderson, J. R. (2015). The social psychology of religion. Using scientific methodologies to understand religion. Construction of Social Psychology: Advances in Psychology and Psychological Trends Series. Lisboa: In Science Press.

Andreoni, J. (1989). Giving with impure altruism: Applications to charity and Ricardian equivalence. Journal of Political Economy, 97(6), 1447–1458.

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The Economic Journal, 100(401), 464–477.

Batson, C. D., Schoenrade, P., & Ventis, W. L. (1993). Religion and the individual: A social-psychological perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Batson, C. D., Floyd, R. B., Meyer, J. M., & Winner, A. L. (1999). “And who is my neighbor?:” Intrinsic religion as a source of universal compassion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 38(4), 445–457.

Beattie, J., & Loomes, G. (1997). The impact of incentives upon risky choice experiments. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 14(2), 155–168.

Becker, G. S. (1974). A theory of social interactions. Journal of Political Economy, 82(6), 1063–1093.

Bekkers, R. (2007). Measuring altruistic behavior in surveys: The all-or-nothing dictator game. Survey Research Methods, 1, 139–144.

Bekkers, R., & Wiepking, P. (2011). A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: Eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(5), 924–973.

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2006). Incentives and prosocial behavior. American Economic Review, 96(5), 1652–1678.

Benz, M., & Meier, S. (2008). Do people behave in experiments as in the field?—Evidence from donations. Experimental Economics, 11(3), 268–281.

Bhogal, M. S., Galbraith, N., & Manktelow, K. (2017). Physical attractiveness, altruism and cooperation in an ultimatum game. Current Psychology, 36(3), 549–555.

Blakey, K. H., Mason, E., Cristea, M., McGuigan, N., & Messer, E. J. (2019). Does kindness always pay? The influence of recipient affection and generosity on young children’s allocation decisions in a resource distribution task. Current Psychology, 38(4), 939–949.

Brooks, A. C. (2003). Religious faith and charitable giving. Policy Review, 121, 39.

Brooks, A. C. (2006). Who really cares: America's charity divide - who gives, who doesn’t, and why it matters. New York, NY: Basic books.

Brunner, E. J. (1998). Free riders or easy riders?: An examination of the voluntary provision of public radio. Public Choice, 97(4), 587–604.

Bryant, W. K., Jeon-Slaughter, H., Kang, H., & Tax, A. (2003). Participation in philanthropic activities: Donating money and time. Journal of Consumer Policy, 26(1), 43–73.

Cardenas, J. C., & Carpenter, J. (2008). Behavioural development economics: Lessons from field labs in the developing world. The Journal of Development Studies, 44(3), 311–338.

Crumpler, H., & Grossman, P. J. (2008). An experimental test of warm glow giving. Journal of Public Economics, 92(5–6), 1011–1021.

Dana, J., Cain, D. M., & Dawes, R. M. (2006). What you don’t know won’t hurt me: Costly (but quiet) exit in dictator games. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 100(2), 193–201.

Dogan, V., & Tiltay, M. A. (2020). Caring about other people’s religiosity levels or not: How relative degree of religiosity and self-construal shape donation intention. Current Psychology, 39(1), 33–41.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (1996). Altruism in anonymous dictator games. Games and Economic Behavior, 16(2), 181–191.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2003). Rebate versus matching: Does how we subsidize charitable contributions matter? Journal of Public Economics, 87, 681–701.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2003). The nature of human altruism. Nature, 425(6960), 785–791.

Fong, C. M., & Luttmer, E. F. (2011). Do fairness and race matter in generosity? Evidence from a nationally representative charity experiment. Journal of Public Economics, 95(5- 6), 372–394.

Forsythe, R., Horowitz, J. L., Savin, N. E., & Sefton, M. (1994). Fairness in simple bargaining experiments. Games and Economic Behavior, 6(3), 347–369.

Franzen, A., & Pointner, S. (2013). The external validity of giving in the dictator game. Experimental Economics, 16(2), 155–169.

Freeman, R. B. (1997). Working for nothing: The supply of volunteer labor. Journal of Labor Economics, 15(1, part 2), S140–S166.

Glazer, A., & Konrad, K. A. (1996). A signaling explanation for charity. The American Economic Review, 86(4), 1019–1028.

Greenway, T. S., Schnitker, S. A., & Shepherd, A. M. (2018). Can prayer increase charitable giving? Examining the effects of intercessory prayer, moral intuitions, and theological orientation on generous behavior. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 28(1), 3–18.

Harbaugh, W. T. (1998a). The prestige motive for making charitable transfers. The American Economic Review, 88(2), 277–282.

Harbaugh, W. T. (1998b). What do donations buy?: A model of philanthropy based on prestige and warm glow. Journal of Public Economics, 67(2), 269–284.

Havens, J. J., O’Herlihy, M. A., & Schervish, P. G. (2006). Charitable giving: How much, by whom, to what, and how. The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook, 2, 542–567.

Helliwell, J. F., Wang, S., & Xu, J. (2016). How durable are social norms? Immigrant trust and generosity in 132 countries. Social Indicators Research, 128(1), 201–219.

Holt, C. A. (1986). Preference reversals and the independence axiom. The American Economic Review, 76(3), 508–515.

House, B. R. (2018). How do social norms influence prosocial development? Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 87–91.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1986). Fairness and the assumptions of economics. Journal of Business, 59, S285–S300.

Leeds, R. (1963). Altruism and the norm of giving. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly of Behavior and Development, 9(3), 229–240.

Mayo, J. W., & Tinsley, C. H. (2009). Warm glow and charitable giving: Why the wealthy do not give more to charity? Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(3), 490–499.

Meer, J. (2011). Brother, can you spare a dime? Peer pressure in charitable solicitation. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7–8), 926–941.

Nemeth, R. J., & Luidens, D. A. (2003). The religious basis of charitable giving in America. Religion as social capital: Producing the common good. Waco: Baylor University Press.

Norenzayan, A., & Shariff, A. F. (2008). The origin and evolution of religious pro sociality. Science, 322(5898), 58–62.

Null, C. (2011). Warm glow, information, and inefficient charitable giving. Journal of Public Economics, 95(5–6), 455–465.

Putnam, R. D., & Campbell, D. E. (2010). American grace: How religion divides and unites us. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Regnerus, M. D., Smith, C., & Sikkink, D. (1998). Who gives to the poor? The influence of religious tradition and political location on the personal generosity of Americans toward the poor. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37(3), 481–493.

Reyniers, D., & Bhalla, R. (2013). Reluctant altruism and peer pressure in charitable giving. Judgment and Decision making, 8(1), 7–15.

Sablosky, R. (2014). Does religion foster generosity? The Social Science Journal, 51(4), 545–555.

Siu, A. M., Shek, D. T., & Law, B. (2012). Prosocial norms as a positive youth development construct: A conceptual review. The Scientific World Journal, 2012, 1–7.

Sosis, R., & Ruffle, B. J. (2003). Religious ritual and cooperation: Testing for a relationship on Israeli religious and secular kibbutzim. Current Anthropology, 44(5), 713–722.

Tonin, M., & Vlassopoulos, M. (2013). Experimental evidence of self-image concerns as motivation for giving. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 90, 19–27.

Umer, H. (2020). Revisiting generosity in the dictator game: Experimental evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 84, 101503.

Vaidyanathan, B., Hill, J. P., & Smith, C. (2011). Religion and charitable financial giving to religious and secular causes: Does political ideology matter? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 50(3), 450–469.

Van Tienen, M., Scheepers, P., Reitsma, J., & Schilderman, H. (2011). The role of religiosity for formal and informal volunteering in the Netherlands. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 22(3), 365–389.

Vesterlund, L. (2006). Why do people give. The nonprofit sector: A research handbook, 2, 168–190.

Vesterlund, L. (2016). Using experimental methods to understand why and how we give to charity. Handbook of Experimental Economics, 2, 91–151.

Wang, L., & Graddy, E. (2008). Social capital, volunteering, and charitable giving. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 19(1), 23–42.

Wiepking, P., & Maas, I. (2009). Resources that make you generous: Effects of social and human resources on charitable giving. Social Forces, 87(4), 1973–1995.

Zizzo, D. J. (2010). Experimenter demand effects in economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 13(1), 75–98.

Acknowledgements

The study was performed as a part of author’s PhD thesis (titled: Essays in Experimental Economics) submitted to the Graduate School of Economics at Waseda University, Tokyo – Japan. The author is International Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) as well as a visiting researcher at the Institute of Economic Research (IER), Hitotsubashi University in Japan. The author would like to thank Doctor Robert Ferenc Veszteg - Professor of Economics at Waseda University and Doctor Alistair Munro – Professor at GRIPS for their valuable comments on the behavioral model and three anonymous reviewers for their useful suggestions.

Code Availability

The STATA code for data analysis is available on request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Statement

The experimental data used in this paper is acquired from the already published papers and hence ethical information is beyond the author’s control.

Informed Consent

The experimental data used in this paper is acquired from the already published papers and hence informed consent is not applicable.

Publication Consent

The experimental data used in this paper is acquired from the already published papers and hence publication consent is not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(XLSX 58 kb)

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Umer, H. A Behavioral model to examine religiosity & generosity. Curr Psychol 42, 1092–1102 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01491-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01491-3