Abstract

Most out-of-home placed children have experienced early adversities, including maltreatment and neglect. A challenge for caregivers is to adequately interpret their foster child’s internal mental states and behavior. We examined caregivers’ mind-mindedness in out-of-home care, and the association among caregivers’ mind-mindedness (and its positive, neutral, and negative valence), recognition of the child’s trauma symptoms, and behavior problems. Participants (N = 138) were foster parents, family-home parents, and residential care workers. Caregivers’ mind-mindedness was assessed with the describe-your-child measure. Caregivers’ recognition of the child’s trauma symptoms, their child’s emotional symptoms, conduct problems, prosocial behavior, and quality of the caregiver-child relationship were assessed using caregivers’ reports. Foster parents produced more mental-state descriptors than did residential care workers. General mind-mindedness, as well as neutral and positive mind-mindedness, related negatively to conduct problems. Besides, positive mind-mindedness was associated with prosocial behavior and neutral mind-mindedness with a better quality of the caregiver-child relationship and fewer child conduct problems. Negative mind-mindedness related positively to the caregiver’s recognition of the child’s trauma symptoms, and indirectly, to emotional symptoms. In conclusion, mind-mindedness seems to be an essential characteristic of out-of-home caregivers, connected to the understanding of their child’s behavior problems and trauma symptoms, as well as to the relationship with the child. The findings suggest a possible use of mind-mindedness in out-of-home care evaluation and intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Children in multiproblem families in the Netherlands are relatively often referred to residential facilities and foster care. In 2017–2018, approximately 1 in almost 100 were placed out-of-home (CBS, 2018); in England, this was 1 in 225 in that period (Department of Education, 2018). Out-of-home care is a regulated process providing placement and services to children who are removed from their homes due to several problems, including maltreatment, parental illness, abuse, or neglect (Brown & Sen, 2014; Lee & Thompson, 2009). Many of the out-of-home placed children have experienced a range of early adversities, including maltreatment and neglect, additionally to the out-of-home placement itself (Greeson et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2001). These children show high rates of internalizing and externalizing behavior, attachment problems, post-traumatic stress, and clinical diagnoses, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders, and depression (Crittenden, 1992; Greeson et al., 2011). They also face a high risk for placement breakdown, such as can happen with foster care placements (Konijn et al., 2019).

One of the biggest challenges of caregivers in out-of-home care is to reflect on and understand the mental states of their children, and to link these mental states to their children’s behaviors and trauma as well as the relationship with their child (Kelly & Salmon, 2014). The present study investigated a specific form of mental-states understanding or caregivers’ mentalization in out-of-home care, mind-mindedness, which is the ability to treat the child as a person with an independent mind (Meins, 1999). Besides, we examined the association between caregivers’ mind-mindedness, their ratings of child trauma, and the quality of the relationship with their child.

In the Netherlands, three primary forms of out-of-home care exist: foster care, family homes, and residential care (Leloux-Opmeer, Kuiper, Swaab, & Scholte, 2017). Foster care concerns the placement of a child with family members (kinship care) or with foster families who have been recruited by a youth care organization. Family homes generally host 4 to 6 out-of-home placed children or adolescents under the supervision of family-home parents who are live-in workers, of whom at least one is a (paid) youth care professional (Lee & Thompson, 2009; Leloux-Opmeer et al., 2017). Residential group facilities typically host 8 to 10 children under the supervision of a team of an equivalent number of residential care workers, mostly working in a schedule of eight hours at a time. Their work includes basic care-taking and child-rearing, and, if needed, provision of individual or group treatment and creation of a therapeutic milieu (Harder, 2018). Residential treatment is considered a ‘last resort’ for youth whose problems could not be addressed by non-residential interventions (Dozier et al., 2014; Harder, 2018; Hellinckx, 2002; Whittaker, Del Valle, & Holmes, 2015), and shows worse outcomes compared to youth with similar problems who are placed in therapeutic foster care (Gutterswijk et al., 2020). Young persons in residential group care have been shown to have the most severe psychosocial problems compared to children in foster care and family homes (Leloux-Opmeer, Kuiper, Swaab, & Scholte, 2016).

The primary aim of all caregivers is to build a positive and secure relationship with the child, which will set the basis for the child’s development of several competencies, including self-regulation of attention, affect, and adaptive behavior (Cook, Blaustein, Spinazzola, & Van der Kolk, 2003). A secure relationship can only be built by comprehending and reflecting on the child’s mental world, or mentalizing about the child (Fonagy, Steele, Steele, Moran, & Higgitt, 1991; Gurney-Smith, Granger, Randle, & Fletcher, 2010; Schofield & Beek, 2005). Little is known, however, about out-of-home caregivers’ mentalization, and in particular their mind-mindedness, as a key component of successful caregiving.

A mind-minded caregiver can infer specific emotions, desires, and thoughts underlying the child’s behavior. In the last 20 years, mind-mindedness has become a well-acknowledged and supported construct reflecting the caregiver’s mental representation of the child (McMahon & Bernier, 2017; Meins, 2013; Zeegers et al., 2018). Mind-mindedness is regarded as a specific characteristic of the caregiver-child relationship (Barreto, Fearon, Osorio, Meins, & Martins, 2016; Meins, Fernyhough, & Harris-Waller, 2014), which has been shown to be temporally stable (Illingworth, MacLean, & Wiggs, 2016), and seems to be only weakly related to the general parental mentalizing abilities (Barreto et al., 2016). Parents’ mind-mindedness is found to be associated with their sensitivity and children’s attachment security (Zeegers et al., 2018) as well as children’s social-cognitive abilities (Centifanti, Meins, & Fernyhough, 2016; Laranjo, Bernier, Meins, & Carlson, 2010, 2014; Lundy, 2013; Meins, Fernyhough, Arnott, Leekam, & de Rosnay, 2013). Hence, a large body of studies demonstrates the relevance of mind-mindedness for the caregiver-child relationship and the child’s social development.

A way to measure caregivers’ mind-mindedness is a single-question interview in which the caregiver is asked to spontaneously describe the child (Meins, Fernyhough, Russell, & Clark-Carter, 1998). This assessment is not a parent’s report, but a measure of parents’ spontaneous production of mental descriptors about the child. The number of produced sentences about the child’s mental characteristics (instead of sentences related to the child’s behavior, physical or situational aspects) provides an indication of the level of the caregiver’s mental representation of the child, or “representational mind-mindedness” (Meins et al., 1998). Besides, each mind-related descriptor can be categorized for its valence, which can be positive (e.g., enthusiastic, smart), negative (e.g., selfish, sad, egoistic) or neutral (e.g., interested in history, willful; Demers, Bernier, Tarabulsy, & Provost, 2010a, b; Walker, Wheatcroft, & Camic, 2012). Although valence has been scarcely used in research on mind-mindedness so far, it can provide more specific indications of the caregiver’s capacity to understand the mental characteristics, or states, of the child. Especially negative mind-related descriptors are important indicators of the capacity to understand and reflect on the child’s more problematic mental states (e.g., anxiety or angriness, negative thoughts, non-adaptive desires).

The association between parental representational mind-mindedness and children’s behavior problems has been scarcely explored (Hughes, Aldercotte, & Foley, 2017; Walker et al., 2012). Walker and colleagues investigated the association between parental mind-mindedness and behavior problems in a community group and in a group of children referred to clinical services. Parents’ mind-mindedness in the clinical group proved to be lower than in the community group. Furthermore, parents’ use of mind-related comments was negatively associated with behavior problems in the community group, but not in the clinical group. Similarly, Hughes and colleagues examined the association between mothers’ mind-mindedness and adolescents’ disruptive behavior in a community sample. They found a negative association between maternal mind-mindedness and children’s disruptive behavior at age 12 years, even when controlling for prior behavior problems at the age of 6, maternal monitoring, family adversity, maternal positivity, and the child’s gender.

Findings on the association between representational mind-mindedness of out-of-home caregivers and their children’s behavioral difficulties are even scarcer. To our knowledge, only Fishburn et al. (2017) investigated differences in mind-mindedness in foster carers, in parents of children living at home and identified as at risk for abuse and neglect (i.e., subject of a child-protection plan, so-called ‘looked after children’), and in parents from a community sample. Foster parents reported more behavior problems than the other two groups, and their representational mind-mindedness was negatively related to children’s behavior problems. The association between children’s behavior problems and mind-mindedness of youth care professionals in residential facilities or family homes has never been investigated. Whether professional caregivers’ mind-mindedness is related to children’s behavior problems remains, therefore, an open question.

The quality of the caregiver-child relationship can be a mechanism involved in the association between caregiver’s mind-mindedness and child behavior. Caregivers who are better able to understand their child’s mental states are also better at taking the child’s perspective and reacting more sensitively and positively during interactions, pre-empting, and defusing everyday conflict situations (Hughes et al., 2017; McMahon & Meins, 2012). As a result, mind-minded caregivers should experience more pleasure and competence and less stress in the relationship with the child. Mind-mindedness has already been found to be related to parental sensitivity, parent-child emotional availability, and attachment security (Zeegers, Colonnesi, Stams, & Meins, 2017). Moreover, positive parent-child relationships have been found to predict less internalizing and externalizing behavior problems in children (e.g., Vieira, Matias, Ferreira, Lopez, & Matos, 2016). Also, a positive relationship between foster parents and their children seems essential for caregivers’ and their children’s well-being (Blythe, Wilkes, & Halcom, 2014).

Another possible mechanism is the caregivers’ recognition of the child’s post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), such as sleeping problems, intrusive recollections, emotional blunting, and concentration problems (Van der Kolk, 2000). Early recognition of PTSS in children is important to offer them appropriate and timely treatment (Verlinden et al., 2014a, b). Caregivers who are better able to tune in with their foster children are expected to be more aware of the impact of PTSS when understanding the child’s behavior. Especially caregivers’ mind-mindedness with negative valence can reflect their understanding of the children’s negative mental states (e.g., anxiety, angry) underlying the PTSS and of the related internalizing and externalizing behaviors (De Haan et al., 2019; Hughes et al., 2017). There is empirical evidence showing that caregivers’ lack of knowledge about their child’s trauma can be a risk factor for successful foster care placement (Sullivan, Murray, & Ake, 2016). Similarly, improving foster parents’ sensitivity to their child’s PTSS symptoms decreases the same symptoms and foster parents’ levels of stress (Gigengack, Hein, Lindeboom, & Lindauer, 2019), increasing the chances of successful foster care placement.

Aims and Hypotheses

In order to support out-of-home caregivers in improving the relationship with their foster children and to stimulate children’s socio-emotional development, it is essential to understand how caregivers’ mental representations of the child relate to the quality of their relationship, the child’s PTSS, and the child’s socio-emotional (mal)adaptation. The first aim of the present study was to investigate representational mind-mindedness and its valence in different types of caregivers – foster parents, family-home parents, and residential care workers – of children who were placed out-of-home. Although research indicates that foster parents produce fewer mind-related descriptors than biological parents do (Fishburn et al., 2017), little is known about the mind-related descriptors of family-home parents and residential care workers. We expected foster parents to be more mind-minded than professional caregivers because of their closer relationship with the foster child and the reported poor therapeutic relationships in residential youth care (Harder, 2018). The second aim was to test the associations among caregivers’ mind-mindedness, children’s behavior problems and prosocial behavior, PTSS, and the quality of the caregiver-child relationship. We expected caregivers’ general and positive mind-mindedness to be negatively associated with children’s behavior problems and positively associated with their prosocial behavior and the quality of the caregiver-child relationship. We expected caregivers’ negative mind-mindedness to be positively associated with their recognition of the child’s PTSS. We also expected caregiver-child relationship quality and caregivers’ recognition of the child’s PTSS to mediate the associations between parents’ mind-mindedness and their child’s behavior.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 138) were foster carers (n = 42), residential care workers (n = 85), and family-home parents (n = 11), and the children they care for; 68 girls and 70 boys. The mean age of the caregivers was 41.69 years (SD = 11.22; Range = 22–71), and the mean age of the children was 13.42 years (SD = 4.49; range 2–18). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the three samples. The original sample included 162 caregivers who participated in the workshop ‘Caring for children who have experienced trauma’ (Coppens & Van Kregten, 2012; Grillo et al., 2010) to improve caregivers’ sensitivity and knowledge about the impact of child’s trauma. The inclusion criterion for the present study was the availability of the mind-mindedness interview and data of at least one of the measures (i.e., the child’s PTSS, caregiver-child relationship quality, child behavior problems, and prosocial behavior) before the workshop.

Procedure

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Ethics Review Board of the University of Amsterdam [n. 2015-CDE-4293]. Data for the present study were gathered before the caregivers started the training ‘Caring for children who have experienced trauma’ (Coppens & Van Kregten, 2012), which was performed at one of the locations of three youth care organizations (Spirit, Bascule, Intermetzo). Thirty to sixty minutes before the beginning of the session, caregivers were first asked to describe their child (i.e., mind-mindedness) and, afterward, to fill out the questionnaire. The biological parents and the out-of-home caregivers signed a written consent form that explained the purpose of the study. Participants were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time. Participants were assured of anonymity and confidentiality and that only research staff and trained students would have access to the questionnaires and interviews.

Instruments

Mind-Mindedness

Mind-mindedness was assessed with the mind-mindedness measure (Meins et al., 1998). Caregivers were asked to describe their child, and their answers were coded following the coding manual of Meins and Fernyhough (2015). The measure has been proven reliable and suitable in previous studies on clinical or at-risk populations (Fishburn et al., 2017; Zeegers, Colonnesi, Noom, Polderman, & Stams, 2019). Mind-related descriptors were categorized by the type of internal state to which the caregiver referred: mental descriptions, emotions, interests, and the child’s preferences, needs, or desires. The other comments were categorized in terms of behavior (e.g., she is very active/energetic, he can be aggressive), physical (e.g., he is five years/tall), or general (e.g., we know his parents, he is living with us since two months) descriptions. The emotional valence of each mind-related descriptor was classified as either positive, negative, or neutral, based on the comments itself (Demers et al., 2010b). Caregivers’ positive mind-mindedness reflects their representation of the child’s mental states as proper for healthy and adaptive development (e.g., he enjoys our company). Conversely, caregivers’ negative mind-mindedness is a manifestation of their representation of the child’s mind in terms of worries, frustration, and consciousness of the child’s difficulties (e.g., she is often sad; she doesn’t trust us). Caregivers’ mental state descriptors with no specific positive or negative valence were classified as neutral (e.g., he has a strong will).

Scores for mind-mindedness were computed as: a) percentage of the total number of mental state descriptors as a measure of general caregivers’ mind-mindedness corrected for verbosity (i.e., total number of mental descriptors/total number of descriptors overall), b) percentages of positive, neutral, and negative mental state descriptors as measures of mind-mindedness with a specific valence (e.g., positive mind-mindedness = total number of positive mental descriptors/total number of descriptors). Trained coders (n = 4) independently rated the interviews and 13% (n = 28) was randomly selected to calculate the inter-rater agreement amongst the coders. Inter-rater agreement on the proportion of mind-related descriptors per transcript was good for the total score (intraclass correlations, ICC = .87) as well as for the valence of positive, neutral, and negative descriptors, ICCs = .86, .86, and .81, respectively.

Child’s PTSS

The child’s PTSS were measured with the 13-items version of the Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES), parental version (Verlinden, Olff, & Lindauer, 2005). Caregivers filled in the questionnaire. The CRIES is based on PTSD symptoms according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). The questionnaire offers three subscale scores on the symptom clusters intrusion (0–20), avoidance (0–20), hyperarousal (0–25), and a total score (0–65). Initial psychometric properties of the CRIES parental version showed good reliability validity and internal consistency (Verlinden et al., 2014a, b). In the present study, the internal consistency was .68 for intrusion, .76 for avoidance, .82 for hyperarousal, and .87 for the total scores. Correlations between intrusion and avoidance was r = .45, p < .001, between intrusion and hyperarousal was r = .67, p < .001, and between avoidance and hyperarousal was r = .47, p < .001. In order to reduce variables for a clearer interpretation of our data, only the total score was used for the statistical analyses.

Caregiver-Child Relationship

The quality of the caregiver-child relationship was assessed with items of the subscale ‘parent-child relationship problems’ of the Parenting Stress Questionnaire (OBVL; Vermulst, Kroes, Meyer, Nguyen, & Veerman, 2015). Caregivers completed the questionnaire. The subscale consists of six items about experienced problems within the caregiver-child relationship formulated in a positive way. Examples of items are “I feel satisfied with this child” and “I feel cheerful when this child is with me.” ‘This child’ refers to the child they professionally care for. The items were rated on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 “not true” to 4 “very true.” Overall reliability and validity of the questionnaire are good (Vermulst et al., 2015). In this study, the reliability was found to be excellent, .93.

Children’s Emotional Symptoms, Conduct Problems, and Prosocial Behavior

Children’s emotional symptoms, conduct problems and prosocial behavior were assessed with the related subscales of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997) completed by the caregiver. Each scale consists of 5 items and each item can be marked as “not true 0”, “somewhat true 1” or “certainly true 2”. Psychometric properties of the SDQ showed good concurrent validity, and internal consistency (Goodman, 1997; Muris, Meesters, & Van den Berg, 2003). In this study, the reliability for emotional symptoms was .76, for conduct problems .75, and for prosocial behavior .82.

Data Preparation and Statistical Analyses

Missing data analysis showed no missing data for Mind-mindedness scores, 6.5% (n = 5 foster parents, 4 residential care workers, 0 family-home parents) for the CRIES scale, 19.6% (n = 25 foster parents, 5 residential care workers, 0 family-home parents) for the Caregiver-child relationship scale, and 15.2% (n = 15 foster parents, 6 residential care workers, 0 family-home parents) for the SDQ scales. According to the Little’s MCAR test, data were not missing completely at random, χ2(9) = 34.35, p = .003. No imputation strategy was used for descriptive analyses, correlations, and ANOVAs. Path analyses were conducted with maximum likelihood estimates (ML; Anderson, 1957) of AMOS (Enders, 2001) ML is an advanced missing data method comparable to Multiple imputations, which handles missing values within the analysis model using all data available information to estimate the model (Collins, Schafer, & Kam, 2001). Mind-mindedness, as well as CRIES, Parent-child relationship and the SDQ scores were normally distributed. We detected one outlier (> 3 SD) for negative mind-mindedness. The value was winsorized by modifying its value to the closest observed values.

Differences between groups of caregivers (foster parents, residential care workers, and family-home parents) on the total mind-mindedness were tested with an ANOVA with groups as between factor. Differences between groups of caregivers on the three valences of mind-mindedness were tested with a repeated-measures ANOVA with valence (positive, neutral, negative) as repeated factor and groups (foster parents, residential care workers, and family-home parents) as between factor. Comparisons were tested with Sidaks’ comparisons and effect sizes were presented in terms of partial eta squared (ŋp2: .01 = small, .06 = medium, .14 = large).

In order to investigate the association between caregiver’s mind-mindedness and child’s behavior problems and prosocial behavior, path analysis models were performed, including the caregiver-child relationship quality and caregivers’ recognition of the child’s PTSS as mediators. The models were tested using the IBM SPSS AMOS package 25.0. Path models were fitted to the variances and covariances of the observed variables, separately for total, positive, neutral, and negative mind-mindedness. All the models were just-identified (fully saturated), so model fit indexes were not evaluated. Path coefficients of the recursive path models, which indicate the strength and the directions of the relations between the constructs, were considered significant at the α = .05 level and were reported in standardized metrics. Mediation effects were computed with the Sobel test (Aroian).

Results

Preliminary Analyses and Impact of Demographic Variables

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the study variables for the three groups of caregivers separately and Table 3 shows Pearson’s correlations between the study variables for the whole group. In line with previous findings (see Leloux-Opmeer et al., 2016, for an overview), children’s age was significantly different in the three groups of caregivers, F(2, 137) = 38.00, p < .001, with foster children being significantly younger than children in residential (p < .001) and family-home care (p < .001). Similar results were found for caregivers’ age, F(2, 133) = 38.85, p < .001, with residential caregivers being significantly younger than foster parents (p < .001) and family-home parents (p < .001). No significant difference was found between caregivers’ experience, F(2, 47) = 0.17, p = .841, and education level, F(2, 50) = 0.40, p = .673. No significant impact was found of demographic variables on the child’s PTSS, quality of the caregiver-child relationship, child’s behavior problems, and prosocial behavior.

Preliminary analyses on the impact of demographic variables showed that the age of the child was significantly and negatively related to child conduct problems in foster families, r(36) = −.42, p = .011, and in residential care, r(70) = −.28, p = .020, and to the caregiver-child relationship, r(60) = −.28, p = .034 in residential care. Caregivers’ age was significantly and negatively associated with the use of positive mind-related comments of residential caregivers, r(82) = −.26, p = .019, and family-home parents, r(11) = −.60, p = .049. No significant effects were found for caregiver’s experience and their education level. The child’s and caregiver’s age were, therefore, included as control variables when testing the associations between mind-mindedness, child’s trauma, caregiver-child relationship, and child’s behavior problems since the three groups were combined to perform the path analysis.

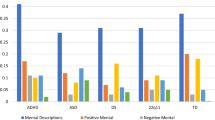

A first repeated-measures ANOVA was performed to test the use of mind-mindedness as within factor (positive, neutral, negative) and the three caregiver groups as between factor (foster parents, residential care workers, family-home parents). A significant effect of caregiver was found, F(2, 135) = 3.38, p = .037. Post-hoc comparisons showed that foster parents produced significantly more mental state descriptors (proportion of total mind-mindedness) than did residential care workers, p = .032; 95% CI [0.15, 4.54], whereas no significant differences were found between foster parents and family-home parents and between residential care workers and family-home parents. Also, there was a significant simple effect of valence, F(2, 270) = 18.56, p < .001, ŋp2 = .12. All caregivers produced significantly more negative than positive, p = .004; 95% CI [1.29, 8.41], and neutral mental state descriptors, p < .001; 95% CI [4.60, 10.56]. No significant interaction effect was found, F(4, 270) = 1.71, p = .149, ŋp2 = .03.

No significant differences between groups were found for caregivers’ recognition of the child’s PTSS, F(2, 128) = 1.92, p = .151, for the caregiver-child relationship, F(2, 110) = 0.08, p = .924, and for children’s prosocial behavior, F(2, 116) = 0.37, p = .692. A repeated measure ANOVA was conducted to test differences between groups for children’s behavior problems. Children’s emotional symptoms and conduct problems were included as within-factor and groups as between-factor. A significant simple effect of problems was found, F(1, 114) = 4.48, p = .037. Emotional symptoms (M = 4.44, SE = 0.33) were more often reported than conduct problems (M = 3.68, SE = 0.34). No significant effect for groups was found, F(2, 114) = 2.35, p = .100, neither a significant interaction effect, F(2, 114) = 0.01, p = .992.

Associations between Mind-Mindedness, Child’s PTSS, Caregiver-Child Relationship, Child’s Behavior Problems and Prosocial Behavior

The four path-analyses (total mind-mindedness; positive mind-mindedness; neutral mind-mindedness; negative mind-mindedness) were performed with child’s and caregiver’s age as covariate. The standardized coefficients of the first path analysis, involving the total proportions of mind-mindedness, are depicted in Fig. 1. Total mind-mindedness was significantly and negatively related to children’s conduct problems, B = −.04 (SE = .02), p = .020, but not to emotional problems, B = −.00 (SE = .02), p = .989, and prosocial behavior, B = .03 (SE = .02), p = .063. Also, no significant associations were found between total percentage of mind-mindedness and the child’s PTSS, B = .15 (SE = .08), p = .061, and the quality of the caregiver-child relationship, B = .02 (SE = .03), p = .620.

Path Analysis with Total (general) Mind-Mindedness as Predictor of Caregivers’ Representation of Child’s Trauma (PTSS), Caregiver-Child relationship, and Child’s Emotional Symptoms, Conduct Problems and Prosocial Behavior, Corrected for the Effects of Caregiver’s and Child’s Age. Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

In the model with percentages of positive mind-mindedness (Fig. 2), mind-mindedness was found to be related to fewer conduct problems, B = −.08 (SE = .03), p < .001, and to more prosocial behavior, B = .05 (SE = .02), p = .018, but no significant relation was found with emotional problems, B = −.02 (SE = .02), p = .356. Also, positive mind-mindedness was not significantly related to the child’s PTSS, B = .01 (SE = .12), p = .937, and to the quality of the caregiver-child relationship, B = .05 (SE = .05), p = .318.

Path Analysis with Positive Mind-Mindedness (MM) as Predictor of Caregivers’ Representation of Child’s Trauma (PTSS), Caregiver-Child relationship, and Child’s Emotional Symptoms, Conduct Problems and Prosocial Behavior, Corrected for the Effects of Caregiver’s and Child’s Age. Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Results on neutral mind-mindedness (Fig. 3) were equivalent to those of total mind-mindedness. That is, a significant and negative association was found between neutral mind-mindedness and conduct problems, B = −.11 (SE = .05), p = .039, but not with emotional problems, B = −.05 (SE = .05), p = .333, prosocial behavior, B = .03 (SE = .05), p = .539, and the child’s PTSS, B = .07 (SE = .24), p = .773. Neutral mind-mindedness was, however, different than total mind-mindedness, significantly related to the quality of the caregiver-child relationship, B = .20 (SE = .10), p = .036. As the quality of the caregiver-child relationship was significantly related to children’s prosocial behavior, B = .23 (SE = .05), p < .001, and conduct problems, B = −.12 (SE = .06), p = .038, mediated associations were tested. The quality of the caregiver-child relationship was no significant mediator of the association between caregivers’ production of neutral mind-related comments and the child’s prosocial behavior, Aroian test = 1.87 (SE = 0.02), p = .060, and conduct problems, Aroian test = 1.40 (SE = 0.02), p = .161.

Path Analysis with Neutral Mind-Mindedness (MM) as Predictor of Caregivers’ Representation of Child’s Trauma (PTSS), Caregiver-Child relationship, and Child’s Emotional Symptoms, Conduct Problems and Prosocial Behavior, Corrected for the Effects of Caregiver’s and Child’s Age. Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Negative mind-mindedness (Fig. 4) did not directly relate to child’s emotion regulation, B = .02 (SE = .02), p = .338, conduct problems, B = −.00 (SE = .03), p = .966, prosocial behavior, B = .01 (SE = .02), p = .694, and the caregiver-child relationship, B = −.02 (SE = .05), p = .753. Negative mind-mindedness was found, however, to be positively and significantly related to the child’s PTSS, B = .33 (SE = .12), p = .005, and the child’s PTSS was associated with emotional problems, B = .11 (SE = .02), p < .001. Mediation test confirmed that the child’s PTSS significantly mediated the associations between the percentages of negative mind-mindedness and emotional symptoms, Aroian test = 2.53 (SE = 0.01), p = .012.

Path Analysis with Negative Mind-Mindedness (MM) as Predictor of Caregivers’ Representation of Child’s Trauma (PTSS), Caregiver-Child relationship, and Child’s Emotional Symptoms, Conduct Problems, and Prosocial Behavior, Corrected for the Effects of Caregiver’s and Child’s Age. Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Discussion

The aim of the present study was twofold. First, we investigated differences between caregivers in three types of out-of-home care (i.e., foster parents, residential care workers, family-home parents) in their levels of mind-mindedness, recognition of the child’s PTSS, quality of the relationship with their child, and children’s social-emotional outcomes. Second, we examined the extent to which caregivers’ mind-mindedness related to children’s socio-emotional problems, the child’s PTSS, and the quality of the caregiver-child relationship. Results showed that, in general, foster parents produced more mental descriptors of their child than did residential care workers. No differences in the valence of mind-mindedness were found between caregivers in different types of out-of-home care, with a higher prevalence of negative than positive and neutral mind-related comments in all three groups. Also, no differences were found between foster parents, residential care workers and family-home parents in the child’s PTSS and quality of the relationship with the child. At the child level, no specific differences were found between children’s behavior problems and prosocial behavior in the three groups of out-of-home care. All children, however, presented more emotional symptoms than conduct problems.

Our results show that caregivers’ use of general mental state descriptors about their child does relate to fewer children’s conduct problems. In addition, the valence of the mind-related descriptors seems of great importance. Positive mind-mindedness was found to be associated with fewer conduct problems and more prosocial behavior, whereas neutral mind-mindedness was related to fewer conduct problems and a better quality of the caregiver-child relationship. Negative mind-mindedness was related to caregivers’ recognition of the child’s PTSS and indirectly to the child’s emotional problems. These findings will be further discussed in terms of differences between types of caregivers and implications of mentalization for the quality of the caregiver-child relationship and children’s social-emotional problems.

Foster parents, when compared with residential care workers, showed a higher level of mind-mindedness, providing more descriptions of their foster child’s emotions, thoughts, intellectual abilities, and preferences. This is probably because foster parents often host one or a small number of children for an extended period of time, which may foster a deeper understanding of the child. On the contrary, residential care workers typically host a relatively large number of children (eight to ten) and, due to working in teams and shifts, spend less time with them. Although residential care workers may sometimes develop closer relationships with some of the children, these relationships are less intense and more transient in nature compared to foster parents’ relationships with their foster children (Harder, 2018; Leloux-Opmeer et al., 2016). Mind-mindedness is a relational construct, and as such, might be higher in closer relationships (Barreto et al., 2016; Meins et al., 2014). Interestingly, family-home parents’ use of mind-mindedness was the average of the other two groups. This confirms that family-home care can be seen as an intermediate setting between foster and residential group care in terms of closeness of caregiver-child relationships (Barth, 2002; Huefner, James, Ringle, Thompson, & Daly, 2010).

While in community samples, parents typically produce more positive and neutral than negative mental state descriptors (McMahon & Meins, 2012), the out-of-home caregivers in the present study produced more negative than positive and neutral mental state descriptors. This does not come as a surprise. Hence, these caregivers look after children with conduct and emotional problems, who present high levels of post-traumatic stress, and often have problematic parent-child relationships (Harder, Knorth, & Kalverboer, 2017; Leloux-Opmeer et al., 2016). It should be noted, however, that no negative association was found between negative mind-mindedness and positive or neutral mind-mindedness, which suggests that the focus on the negative mental aspects of the child did not impede caregivers to report about the positive or neutral aspects of the child during the interview.

In line with Fishburn et al. (2017), caregivers’ general production of mental state descriptors was negatively associated with children’s behavior problems. The negative association between caregivers’ mind-mindedness and children’s conduct problems is in line with previous findings on foster parents (Fishburn et al., 2017) and biological parents (Hughes et al., 2017; Walker et al., 2012). The results are also in line with previous studies in which the same association was investigated measuring parents’ mind-mindedness during parent-child interaction (e.g., Camisasca, Procaccia, Miragoli, Valtolina, & Di Blasio, 2017; Colonnesi, Zeegers, Majdandžić, Van Steensel, & Bögels, 2019). This finding suggests that children’s externalizing problems might direct caregivers’ attention to their behavior, hindering their capacity to understand the mental states of their child (Colonnesi et al., 2019). In the long term, the lack of caregivers’ understanding can increase the child’s behavior problems, resulting in a vicious circle between the caregiver and the child.

A more in-depth analysis of caregivers’ mind-mindedness in which valence was taken into consideration revealed more specific associations with the other study variables. A possible explanation is that while total mind-mindedness is an indication of the caregivers’ capacity to mentalize about their child, the sub-dimensions (positive, neutral, and negative) of mind-mindedness provide insight into the way caregivers mentalize about the positive and problematic mental aspects of the child. Hence, when investigating at-risk populations, such as children in out-of-home care, the valence of caregivers’ mind-mindedness can be key to understand the impact of mentalization on the relationship with the child.

As expected, positive mind-mindedness was associated with fewer conduct problems and more prosocial behavior. Caregivers are better able to provide descriptions of their children based on the child’s positive desires, thoughts, intentions, and emotions when children are more socially competent and do not display externalizing behavior. Previous studies already found a positive association between mind-mindedness and children’s social-developmental capacities (Centifanti et al., 2016; Laranjo et al., 2010, 2014; Lundy, 2013; Meins et al., 1998; Meins et al., 2013). This association should be considered as bidirectional, since caregivers who produce more positive mind-mindedness display more sensitive behavior towards the child (Demers et al., 2010b; McMahon & Meins, 2012), which, in turn, facilitates the child’s social-emotional development (Zeegers et al., 2017). Interestingly, the child’s PTSS and the quality of the caregiver-child relationship were not related to the caregivers’ production of positive mind-related descriptions, nor did they mediate the associations between positive mind-mindedness and child’s behavior. Caregivers’ appreciation of positive mental states in their child seems to be independent of their relationship and the child’s trauma symptoms.

Although caregivers’ use of neutral mind-related descriptors showed similarities to those of general and positive mind-mindedness, neutral mind-related descriptors were also related to the quality of the caregiver-child relationship. Neutral mind-mindedness concerns descriptors that can have both (or neither) a positive or negative valence (e.g., is a sensitive child, wants to be a leader, is critical towards things), or that describe the child in ways that go beyond the valence. For these reasons, neutral mind-mindedness can be an index of mentalization in closer relationships and indicate a stronger mental connection between caregiver and child (e.g., Chaparro & Grusec, 2015; Padilla-Walker & Son, 2019).

The findings with the strongest implications are probably the association between the caregivers’ production of negative mind-related descriptors and the child’s PTSS, and the mediation of the child’s PTSS of the association between mind-mindedness and emotional symptoms. The results suggest that the caregivers’ ability to understand and report on the negative mental states behind their child’s emotional symptoms occurs through the understanding of their child’s PTSS. As we already argued, negative mind-mindedness should not be considered a lack of mind-mindedness, but as a reflection of mentalization focused on the child’s less adaptive internal states (e.g., anxiety, sadness, frustrations, not acceptance, or negative thoughts or interpretations). It should also be noted that negative mind-mindedness was not related to the caregiver-child relationship, suggesting that caregivers’ negative mind-related descriptors of the child are independent of the quality of the caregiver-child relationship. At the beginning of clinical interventions, negative mind-mindedness can offer a precious index of caregivers’ ability to connect children’s behavior problems and trauma symptoms to the related negative mental states. The understanding of these mental states can be the starting point of a successful intervention (Kelly & Salmon, 2014).

The present study had some limitations that should be addressed in future studies. First, the associations between the child’s PTSS, the quality of the caregiver-child relationship, children’s behavior problems and prosocial behavior should be interpreted with caution because of the lack of multiple informants. Future research should combine multiple respondents’ reports (e.g., child report) and observational measures. A second limitation is the limited number of participants, especially in the group of family-home parents (n = 11), which qualifies the study as the first investigation of out-of-home caregivers’ mind-mindedness that needs to be replicated with a larger group. Because of a lack of statistical power, the associations between parental mind-mindedness and the other caregivers’ and child’s aspects could not be tested separately in the three groups. Future research should focus on the three different groups of caregivers separately, including possible moderators and mediators that are specific for these caregivers (e.g., kinship vs. non-kinship in the group of foster parents). A third limitation of the present study is its cross-sectional and non-experimental design, which does not allow (causal) conclusions about the direction of the associations. Experimental-longitudinal research is needed to investigate the impact of caregivers’ mentalization on caregivers-child relationships and child outcomes.

In conclusion, the representational mind-mindedness appears to be an essential characteristic of out-of-home caregivers. The high proportion of mind-mindedness in foster parents, as compared with residential care workers, confirms the assumption that mind-mindedness is a relationship-specific construct, and as such, it is higher in closer relationships. Our results also show that the production of mind-mindedness, as general capacity as well as with a specific valence, is associated with children’s socio-emotional problems and quality of the caregiver-child relationships. In particular, mind-mindedness with a negative valence may be the way caregivers mentalize about their child in out-of-home care when post-traumatic stress is high and emotional problems are present. Although we cannot make inferences about the direction of these associations, it is worth investigating whether interventions that target caregivers’ recognition of the child’s mental states can improve their sensitivity toward children’s PTSS, and subsequently decrease related internalizing and externalizing behavior problems.

References

Anderson, T. W. (1957). Maximum likelihood estimates for a multivariate Normal distribution when some observations are missing. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 52(278), 200–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415616200.

Barreto, A. L., Fearon, R. M. P., Osorio, A., Meins, E., & Martins, C. (2016). Are adult mentalizing abilities associated with mind-mindedness? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40, 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415616200.

Barth, R. P. (2002). Institutions vs. foster homes: The empirical base for the second century of debate. Chapel Hill, NC: Annie E. Casey Foundation, University of North Carolina, School of Social Work, Jordan Institute for Families.

Blythe, S. L., Wilkes, L., & Halcomb, E. J. (2014). The foster carer’s experience: An integrative review. Collegian, 21(1), 21–32.

Brown, L., & Sen, R. (2014). Improving outcomes for looked after children: A critical analysis of kinship care. Practice, 26, 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2014.914163.

Camisasca, E., Procaccia, R., Miragoli, S., Valtolina, G. G., & Di Blasio, P. (2017). Maternal mind-mindedness as a linking mechanism between childbirth-related post-traumatic stress symptoms and parenting stress. Health Care for Women International, 38(6), 593–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2017.1296840.

Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS). (2018). Jeugdhulp [Youth care]. Den Haag, the Netherlands: CBS.

Centifanti, L. C. M., Meins, E., & Fernyhough, C. (2016). Callous-unemotional traits and impulsivity: Distinct longitudinal relations with mind-mindedness and understanding of others. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 57(1), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12445.

Chaparro, M. P., & Grusec, J. E. (2015). Parent and adolescent intentions to disclose and links to positive social behavior. Journal of Family Psychology, 29, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000040.

Collins, L. M., Schafer, J. L., & Kam, C. M. (2001). A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods, 6(4), 330–351.

Colonnesi, C., Zeegers, M. A. J., Majdandžić, M., Van Steensel, F. J. A., & Bögels, S. M. (2019). Fathers’ and mothers’ early mind-mindedness predicts social competence and behavior problems in childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47, 1421–1435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-019-00537-2.

Cook, A., Blaustein, M., Spinazzola, J., & Van der Kolk, B. (2003). Complex trauma in children and adolescents: White paper from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network Complex Trauma Task Force. Los Angeles and Durham: National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

Coppens, L., & Van Kregten, C. (2012). Zorgen voor getraumatiseerde kinderen: Een training voor opvoeders van kinderen met complex trauma. [caring for children who have experienced trauma: A training for resource parents of complex traumatized children]. Houten: Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum.

Crittenden, P. (1992). Children’s strategies for coping with adverse home environments: An interpretation using attachment theory. Child Abuse & Neglect, 16, 329–343.

De Haan, A., Landolt, M., Fried, E., Kleinke, K., Alisic, E., Bryant, R., et al. (2019). Dysfunctional post-traumatic cognitions, post-traumatic stress, and depression in children and adolescents exposed to trauma: A network analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61, 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13101.

Demers, I., Bernier, A., Tarabulsy, G. M., & Provost, M. A. (2010a). Maternal and child characteristics as antecedents of maternal mind-mindedness. Infant Mental Health Journal, 31(1), 94–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20244.

Demers, I., Bernier, A., Tarabulsy, G. M., & Provost, M. A. (2010b). Mind-mindedness in adult and adolescent mothers: Relations to maternal sensitivity and infant attachment. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 34(6), 529–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025410365802.

Department of Education (2018). Children looked after in England including adoption: 2017 to 2018. National Statistics. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/children-looked-after-in-england-including-adoption-2017-to-2018.

Dozier, M., Kaufman, J., Kobak, R., O’Connor, T. G., Sagi-Schwartz, A., Scott, S., Shauffer, C., Smetana, J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Zeanah, C. H. (2014). Consensus statement on group care for children and adolescents: A statement of policy of the American Orthopsychiatric Association. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84, 219–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000005.

Enders, C. K. (2001). A primer on maximum likelihood algorithms available for use with missing data. Structural Equation Modeling, 8, 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0801_7.

Fishburn, S., Meins, E., Greenhow, S., Jones, C., Hackett, S., Biehal, N., Baldwin, H., Cusworth, L., & Wade, J. (2017). Mind-mindedness in parents of looked-after children. Developmental Psychology, 53, 1954–1965. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000304.

Fonagy, P., Steele, M., Steele, H., Moran, G. S., & Higgitt, A. C. (1991). The capacity for understanding mental states: The reflective self in parent and child and its significance for security of attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 12, 201–218.

Gigengack, M. R., Hein, I. M., Lindeboom, R., & Lindauer, R. J. (2019). Increasing resource parents’ sensitivity towards child posttraumatic stress symptoms: A descriptive study on a trauma-informed resource parent training. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 12, 23–29.

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 38, 581–586.

Greeson, J., Briggs, E., Kisiel, C., Layne, C., Ake, G., Ko, S., Gerrity, E., Steinberg, E., Howard, M., Pynoos, R., & Fairbank, J. (2011). Complex trauma and mental health in children and adolescents placed in foster care: Findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Child Welfare, 90, 91–108.

Grillo, C. A., Lott, D. A., & the Foster Care Subcommittee of the Child Welfare Committee, National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2010). Caring for children who have experienced trauma: A workshop for resource parents—Facilitator’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

Gurney-Smith, B., Granger, C., Randle, A., & Fletcher, J. (2010). ‘In time and in tune’—The fostering attachments group: Capturing sustained change in both caregiver and child. Adoption & Fostering, 34, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/030857591003400406.

Gutterswijk, R, V., Kuiper, C, H, Z, Lautan, N., Kunst, E, G., van der Horst, F, C, P, Stams, G, J, J,M., & Prinzie, P, J. (2020). The outcome of non-residential youth care compared to residential youth care: A multilevel meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104950.

Harder, A. T. (2018). Residential care and cure: Achieving enduring behavior change with youth by using a self-determination, common factors and motivational interviewing approach. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 35, 317–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2018.1460006.

Harder, A. T., Knorth, E. J., & Kalverboer, M. E. (2017). The inside out? Views of young people, parents, and professionals regarding successful secure residential care. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 34, 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-016-0473-1.

Hellinckx, W. (2002). Residential care: Last resort or vital link in child welfare? International Journal of Child and Family Welfare, 5, 75–83.

Huefner, J. C., James, S., Ringle, J., Thompson, R. W., & Daly, D. L. (2010). Patterns of movement for youth within an integrated continuum of residential services. Children and Youth Services Review, 32, 857–864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.02.005.

Hughes, C., Aldercotte, A., & Foley, S. (2017). Maternal mind-mindedness provides a buffer for pre-adolescents at risk for disruptive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45, 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0165-5.

Illingworth, G., MacLean, M., & Wiggs, L. (2016). Maternal mind-mindedness: Stability over time and consistency across relationships. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13, 488–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2015.1115342.

Kelly, W., & Salmon, K. (2014). Helping foster parents understand the foster child’s perspective: A relational learning framework for foster care. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19, 535–547. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104514524067.

Konijn, C., Admiraal, S., Baart, J., van Rooij, F., Stams, G. J., Colonnesi, C., Lindauer, R., & Assink, M. (2019). Foster care placement instability: A meta-analytic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 96, 483–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.12.002.

Laranjo, J., Bernier, A., Meins, E., & Carlson, S. M. (2010). Early manifestations of Children’s theory of mind: The roles of maternal mind-mindedness and infant security of attachment. Infancy, 15(3), 300–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7078.2009.00014.x.

Laranjo, J., Bernier, A., Meins, E., & Carlson, S. M. (2014). The roles of maternal mind-mindedness and infant security of attachment in predicting preschoolers’ understanding of visual perspective taking and false belief. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 125, 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2014.02.005.

Lee, B., & Thompson, R. (2009). Examining externalizing behavior trajectories of youth in group homes: Is there evidence for peer contagion? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9254-4.

Leloux-Opmeer, H., Kuiper, C. H. Z., Swaab, H. T., & Scholte, E. M. (2016). Characteristics of children in Foster Care, family-style group care, and residential care: A scoping review. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 2357–2371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0418-5.

Leloux-Opmeer, H., Kuiper, C. H. Z., Swaab, H. T., & Scholte, E. M. (2017). Children referred to foster care, family-style group care, and residential care: (how) do they differ? Children and Youth Services Review, 77, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.03.018.

Lundy, B. L. (2013). Paternal and maternal mind-mindedness and preschoolers’ theory of mind: The mediating role of interactional attunement. Social Development, 22(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12009.

McMahon, C. A., & Bernier, A. (2017). Twenty years of research on parental mind-mindedness: Empirical findings, theoretical and methodological challenges, and new directions. Developmental Review, 46, 54–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2017.07.001.

McMahon, C. A., & Meins, E. (2012). Mind-mindedness, parenting stress, and emotional availability in mothers of preschoolers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27, 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.08.002.

Meins, E. (1999). Sensitivity, security and internal working models: Bridging the transmission gap. Attachment & Human Development, 1, 325–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616739900134181.

Meins, E. (2013). Sensitive attunement to infants’ internal states: Operationalizing the construct of mind-mindedness. Attachment & Human Development, 15(5–6), 524–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2013.830388.

Meins, E., & Fernyhough, C. (2015). Mind-mindedness coding manual, version 2.2. Unpublished manuscript. York: University of York.

Meins, E., Fernyhough, C., Russell, J., & Clark-Carter, D. (1998). Security of attachment as a predictor of symbolic and Mentalising abilities: A longitudinal study. Social Development, 7(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00047.

Meins, E., Fernyhough, C., Arnott, B., Leekam, S. R., & de Rosnay, M. (2013). Mind-mindedness and theory of mind: Mediating roles of language and perspectival symbolic play. Child Development, 84, 1777–1790. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12061.

Meins, E., Fernyhough, C., & Harris-Waller, J. (2014). Is mind-mindedness trait-like or a quality of close relationships? Evidence from descriptions of significant others, famous people, and works of art. Cognition, 130, 417–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2013.11.009.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Van den Berg, F. (2003). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ). Further evidence for its reliability and validity in a community sample of Dutch children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 12(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-003-0298-2.

Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Son, D. (2019). Longitudinal associations among routine disclosure, the parent–child relationship, and adolescents’ prosocial and delinquent behaviors. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36, 1853–1871. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407518773900.

Schofield, G., & Beek, M. (2005). Providing a secure base: Parenting children in long-term foster family care. Attachment & Human Development, 7, 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500049019.

Stein, B. D., Zima, B. T., Elliott, M. N., Burnam, M. A., Shahinfar, A., Fox, N. A., & Leavitt, L. A. (2001). Violence exposure among school-age children in foster care: Relationship to distress symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 588–594. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200105000-00019.

Sullivan, K. M., Murray, K. J., & Ake, G. S. (2016). Trauma-informed care for children in the child welfare system: An initial evaluation of a trauma-informed parenting workshop. Child Maltreatment, 21, 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559515615961.

Van der Kolk, B. (2000). PTSD and the nature of trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2(1), 1–16.

Verlinden, E., Olff, M., & Lindauer, R. J. L. (2005). Dutch version of the Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES-13) parent version. Children and War Foundation. https://www.childrenandwar.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/cries_13_UK.

Verlinden, E., Van Meijel, E., Opmeer, B., Beer, R., De Roos, C., Bicanic, I., Lamers-Winkelman, F., Olff, M., Boer, F., & Lindauer, R. (2014a). Characteristics of the Children’s revised impact of event scale in a clinically referred Dutch sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(3), 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21910.

Verlinden, E., Van Laar, Y., Van Meijel, E., Opmeer, B., Beer, R., de Roos, C., Bicanic, I., Lamers-Winkelman, F., Olff, M., Boer, F., & Lindauer, R. (2014b). A parental tool to screen for posttraumatic stress in children: First psychometric results. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27, 492–495. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21929.

Vermulst, A., Kroes, G., Meyer, R., Nguyen, L., & Veerman, J. W. (2015). Handleiding OBVL [guideline parenting stress questionnaire]. Nijmegen: Praktikon.

Vieira, J. M., Matias, M., Ferreira, T., Lopez, F. G., & Matos, P. M. (2016). Parents’ work-family experiences and children’s problem behaviors: The mediating role of the parent–child relationship. Journal of Family Psychology, 30, 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000189.

Walker, T. M., Wheatcroft, R., & Camic, P. M. (2012). Mind-mindedness in parents of pre-Schoolers: A comparison between clinical and community samples. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17, 318–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104511409142.

Whittaker, J. K., Del Valle, J. F., & Holmes, L. (Eds.). (2015). Therapeutic residential care for children and youth developing evidence-based international practice. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Zeegers, M., Colonnesi, C., Stams, G. J., & Meins, E. (2017). Mind matters: A meta-analysis on parental Mentalization and sensitivity as predictors of infant–parent attachment. Psychological Bulletin, 143, 1245–1272. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000114.

Zeegers, M., De Vente, W., Nikolić, M., Majdandžić, M., Bögels, S. M., & Colonnesi, C. (2018). Mothers’ and fathers’ mind-mindedness influences physiological emotion regulation of infants across the first year of life. Developmental Science, 21, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12689.

Zeegers, M., Colonnesi, C., Noom, M., Polderman, N., & Stams, G. J. J. M. (2019). Remediating child attachment insecurity: Evaluating the basic trust intervention in adoptive families. Research on Social Work Practice, 30, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731519863106.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Funding

This research was supported by The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development under Grant 70-72900-98-14038.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Cristina Colonnesi and Carolien Konijn designed the study. Carolien Konijn organized the data collection. Cristina Colonnesi conducted the statistical analyses. Cristina Colonnesi and Carolien Konijn wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Colonnesi, C., Konijn, C., Kroneman, L. et al. Mind-mindedness in out-of-home Care for Children: Implications for caregivers and child. Curr Psychol 41, 7718–7730 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01271-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01271-5