Abstract

People make choices among different options for different reasons. We hypothesized that people will choose the options that they believe will make them happier and that this effect of anticipated happiness on decision-making will be moderated by style of thinking (i.e., intuitive or deliberative). In a two-phase online experiment, 15 pairs of options were randomly presented one at a time, and participants indicated the extent to which each option would contribute to their happiness (i.e. anticipated happiness of a choice option). One week later, participants were randomly assigned to make choices on similar pairs of options either by using deliberative thinking or intuitive thinking. Results of a linear mixed-effects model analysis revealed that anticipated happiness influenced choices significantly. However, this occurred independent of whether participants made the choice in a deliberative or in an intuitive mindset. The implications of these findings for understanding the association between decision-making and happiness are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

People naturally want to be happy (Howell et al., 2016; King & Napa, 1998). Indeed, several studies have demonstrated that happiness is rated as one of the most important goals across countries and cultures (Diener & Oishi, 2004; King & Broyles, 1997; King & Napa, 1998). While people differ in their idiosyncratic beliefs about happiness, lay beliefs about happiness tend to concur quite strongly with the scientific definition of happiness, that is a high level of life satisfaction, and the frequent experience of positive and infrequent experience of negative affect (e.g., Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999; Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade, 2005). One of the reasons that people strive for happiness may be the fact that it is associated with many advantages, such as increased mental and physical health, superior work outcomes, and larger social rewards (Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005; Diener & Seligman, 2002).

Given the importance people attach to happiness, it seems reasonable to expect that decisions that people make are for a large part driven by the anticipated happiness the choice or decision would bring, which we refer to as the anticipated happiness utility of a choice. That is, if an individual has to choose between options A and B, we could hypothesize that the person would choose option A if she believes that choosing option A would make her happier than choosing option B. It seems clear, however, that in real life people not always make optimal choices in terms of anticipated happiness utility, and in fact sometimes people make decisions that undermine happiness. For example, one may choose spending the weekend playing video games instead of spending it with family, even though one may have the knowledge that being with family will promote feelings of happiness. In the current study, we examined two related questions: First, do people make decisions based on anticipated happiness utility? And second, under what circumstances are people most likely to choose based on anticipated happiness utility? Specifically, and as will be explained in more detail shortly, we examined the hypothesis that anticipated happiness utility will determine people’s choice particularly if they choose intuitively, and less so when they choose in a more deliberative fashion.

Do People Choose Based on Anticipated Happiness?

Emotion-based choice theory (Mellers & Mcgraw, 2001; Mellers, Schwartz, & Ritov, 1999) suggests that decisions are influenced by anticipated emotions. People often anticipate the pleasure or pain they might experience as a result of a decision. When having to make a choice, individuals imagine what it would feel like when choosing any of the given options. These anticipated emotions toward the options then guide the actual choice. That is, people choose the option with the highest level of subjective anticipated pleasure (e.g., Mellers & Mcgraw, 2001). People not only take anticipated pleasure into account, but also consider other emotions like regret and disappointment. For example, several studies demonstrated the impact of anticipated regret and disappointment on decision-making (Abraham & Sheeran, 2004; Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2004). Previous research has found support for the function of anticipated emotions on decision-making in insurance decisions (Hsee & Kunreuther, 2000), purchase intentions (Bagozzi, Belanche, Casaló, & Flavián, 2016), risky decisions (Rottenstreich & Hsee, 2001), and negotiations (Kong, Tuncel, & Parks, 2011).

In addition to anticipating specific emotions of different choice options, people may make predictions about the impact a certain choice has on the overall sense of happiness it will bring (i.e., anticipated happiness utility of a choice). There is some previous support for this idea. Benjamin, Heffetz, Kimball, and Rees-Jones (2012) presented a series of hypothetical pairwise-choice scenarios that emphasized a tradeoff between two options, and subsequently asked participants which of the options would make them happier (i.e., anticipated happiness question) and which option they think they would choose (i.e., choice question). For example, participants indicated for the options “sleep less but earn more” versus “earn more but sleep less” to what extent they thought which of these two options would make them happier, and then directly thereafter (i.e., in the same questionnaire) they indicated to what extent they thought they would choose one over the other option. It was found that participants’ responses toward the anticipated happiness question coincided with the choices that they made, implying that indeed people choose based on the anticipated happiness utility of choice options. One aim of the current research is to see whether we can replicate these findings, using a similar paradigm (but with some notable differences as will be explained below).

When Are People More, or Less, Likely to Make Choices Based on Anticipated Happiness Utility?

As noted earlier, in real life people do not always make choices that indeed would result in more happiness. For example, many people invest most of their time on work and on gaining more money rather than on fostering relationships with a romantic partner, friends, and family, even though maintaining relationships with close others tends to be more strongly associated with happiness than money (Mogilner, 2010). Similarly, while research shows that buying experiences generally results in more happiness than buying material goods (Howell & Guevara, 2013), people often tend to choose material goods rather than experiences. More generally, rather than making choices on anticipated happiness, people may choose based on certain general rules (e.g., Prelec & Herrnstein, 1991). One example of such rules is the so-called ‘seek variety’ rule (Simonson, 1990). Rather than choosing the option that is most preferred, and would probably bring more happiness, people tend to vary their choices simply for the sake of seeking variety (e.g., Simonson, 1990). Moreover, people often may make choices based on norms, and based on what they believe is expected from them, rather than based on what would bring them more happiness (e.g., Dundes, Cho, & Kwak, 2009).

Hence, an interesting question is when people are more likely to make choices based on what makes them most happy, and when are they less likely to do so. This is the second aim we have in the current research. Specifically, we examine the hypothesis that when people choose intuitively, their choices will be guided more strongly based on the anticipated level of happiness of the choice. In contrast, when thinking carefully and deliberatively before making a choice, anticipated happiness of a choice may be less strongly predictive of the actual choices that people make.

We based our hypothesis on dual-process theories of cognition and decision-making (Chaiken & Trope, 1999; Evans, 2003, 2008, 2010; Kahneman, 2011; Kahneman & Frederick, 2012). In a very broad sense, such theories suggest that people process information in two ways, “one variously labeled the intuitive, automatic, natural, nonverbal, narrative, and experiential, and the other analytical, deliberative, verbal, and rational”, as suggested by Epstein (1994, p. 710). Research has shown that people have different preferences in using either intuitive or deliberative ways of thinking and decision-making (Betsch, 2004; Kahneman, 2011). The preferred thinking strategy becomes a habitual way of responding, and a stable preference for organizing and processing information and experience (i.e., cognitive styles) (Betsch & Kunz, 2008; Messick, 1976). When choosing between different options, intuitive thinkers consider their initial affective reactions toward the options, while deliberative thinkers rely on a more careful analysis of the pros and the cons of the available options (de Vries, Holland, & Witteman, 2008).

Intuitive thinking is thought to be closely related with the use of affect and heuristics in human decision-making and behavior. For example, according to Slovic, Finucane, Peters, and MacGregor (2007), people may employ an “affect heuristic” to make decisions and judgments, which is a quick and intuitive assessment of “how do I feel about a possible choice?”. We argue that anticipated happiness may serve as such an affect heuristic, and that intuitive thinkers would be especially likely to base their choices on anticipated happiness. People estimate which choice would make them most happy, and when choosing without too much deliberation (i.e. intuitively), this anticipated happiness information is used to actually make a choice. In contrast, when thinking deliberatively before making a choice, such affective information may be overruled by non-affective factors (e.g., de Vries, Fagerlin, Witteman, & Scherer, 2013; Phillips, Fletcher, Marks, & Hine, 2016; Wilson & Schooler, 1991). For example, when thinking carefully before making a choice people may deliberate about normative aspects of the choice that could undermine the more affective influences (such as anticipated happiness) on a choice. Indeed, and in line with this general reasoning, research has shown that when people introspect on the reasons for making a particular choice, they tend to be less satisfied after making the decision, as compared to when they make a choice intuitively (Dijksterhuis & van Olden, 2006; Wilson et al., 1993). This may suggest, as we predict, that when making a choice based on careful deliberation, people use or weigh anticipated happiness of the choice less strongly.

The Present Research

Thus, the present research examines two hypotheses, namely 1) that there is an effect of anticipated happiness on choice, and 2) that the effect of anticipated happiness on choice is stronger when people make their choices intuitively rather than deliberatively. We examined these predictions by having participants, in phase one, indicate the level of anticipated happiness for several choice options and then, in phase two about a week later, indicate which of the options they would actually choose. Half of the participants did this choice task in phase 2 with the instruction to make choices intuitively, the other half was instructed to deliberately think about the choice options before making the choices. Aside from experimentally manipulating intuitive and deliberative thinking styles, we also measured individual differences in the preferred style of thinking. In sum, we expected that participants’ choices in phase 2 would be predicted by the anticipated happiness utility of the choice options as indicated in phase 1 (Hypothesis 1). Furthermore, we hypothesized that the effect of anticipated happiness on choice would be stronger in the intuitive versus deliberative condition (Hypothesis 2a), and would be stronger among participants with a higher self-reported dispositional preference for intuitive rather than deliberative thinking (Hypothesis 2b).

Method

Design

We used a between-subjects design with thinking style (deliberative versus intuitive) as a categorical independent variable, anticipated happiness utility as a continuous independent variable, and choice as a continuous dependent variable. The experiment was pre-registered. The hypotheses, materials, and analysis plan for the study are accessible at the OSF, a public repository website (https://osf.io/63f2j). There are no significant deviations between the actual study and the pre-registered plan, except for the different terminologies used to indicate the variablesFootnote 1 and the actual syntax used to test the model. We mention the actual syntax in the data analysis section below.

Participants

A total of 150 adults were recruited in the first phase of the study from Prolific.ac, a subject pool for online studies. Only 141 participants returned for the second phase. Prior to data collection, the sample size was calculated based on a power analysis using PANGEA v0.2 (Westfall, 2016), an open-source web-based power application. According to Westfall (2016, p.23), a medium effect size of 0.45 “represents a reasonable suggestion for most psychological studies if one has no other information about the specific effect to be studied”. Following this suggestion, we adopted this standard to calculate the sample size because we could not find an expected effect size in existing literature (e.g., Benjamin et al., 2012). Other parameters used for the sample size calculation are provided in Appendix A. The recruitment was stopped when we reached the predetermined sample size. One participant was excluded because he/she indicated not to use his/her data in a self-reported measure for identifying careless participants (i.e., “In your honest opinion, should we use your data?”; Meade & Craig, 2012). Thus, 140 participants were included in the final analyses (38% male, age ranged 18–65 years old, M = 37.46, SD = 12.12).

Participants were UK (81%) and the US (19%) citizens. 91% was Caucasian, 6% Asian, 1% African, 1% Latino/Hispanic, and 1% belonged to other ethnicities. 37% was full-time employee, 22% part-time employee, 11% homemaker, 9% self-employed, 7% student, 5% unemployed, 3% retired, and 6% other work. The educational backgrounds were 37% bachelor’s degree, 34% high school, 15% vocational education, 7% master’s degree, 7% other education. Their relationship statuses were 32% single, 30% in a relationship, 29% married, 6% divorced, 2% engaged, and 1% widowed.

Procedures and Materials

The procedures we used in the present research were adapted from Benjamin et al. (2012). Participants were requested to participate in a two-phase online study. The first phase (i.e., the anticipated happiness of options) and the second phase (i.e., choice) were presented with an interval of 5 to 10 days. Participants received a total of £2 for their participation in the study. A general description of what was expected from participants was posted on www.prolific.ac. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. After providing informed consent, participants received the link to the first phase of the study.

In this phase, participants indicated their anticipated level of happiness for a number of choice options. Specifically, participants were presented with 15 pairs of options in random order. The options represented hypothetical life events in six life domains, that are found to be associated with happiness in previous studies (e.g., Diener & Fujita, 1995; i.e. romantic relationship, health, leisure, money, friendship, and job). Each pair consisted of two options of which one was presented on the left side (i.e., Option A; e.g., “A warm date with someone you love”) and the other on the right side (i.e., Option B; e.g., “Exercise in your favorite gym”) of the computer screen.

Participants responded to the following anticipated happiness question: “Between these two options, how much do you think one option would contribute to your happiness relative to the other one?”, using a 100-point slider by sliding the bar in the middle of the slider toward the most contributing option. The score of 0 indicated that Option A (i.e., the one on the left side of the screen) contributed the most to happiness relative to Option B (i.e., the one on the right side of the screen), the score of 100 indicated that Option A contributed the least to happiness relative to Option B, and vice versa for Option B (see Appendix B for the complete pairs of options and anticipated happiness instruction). All choice options were presented in a randomized order, and the location of the options on the screen (left/right) was also randomized.

After indicating the level of anticipated happiness for all choices in phase 1, participants reported their preference for decision-making style (i.e., intuitive/deliberative) on the Preference for Intuitive/Deliberative Scale (PID; Betsch, 2004). The scale comprises of 9 items measuring preference for intuitive thinking (PID-I, i.e., “I listen carefully to my deepest feelings”), and 9 items measuring preference for deliberative thinking (PID-D, i.e., “Before making decisions I think them through”). Participants responded using 5-point Likert scale (1 = very much disagree, 5 = very much agree; α = .78 and .77, for PID-I and PID-D, respectively). Higher mean scores in PID-I indicated a stronger preference for intuitive thinking. Similarly, higher mean scores in PID-D indicated a stronger preference for deliberative thinking. Finally, participants filled out some demographic questions (i.e. age, sex, educational, work, ethnicity background, and marital status).Footnote 2

Five to ten days later, participants received an email directing them to the second phase of the study. In this phase, they were randomly assigned to either the intuitive condition (n = 69) or the deliberative condition (n = 71). Depending on the condition, participants received different instructions. Participants in the deliberative condition were instructed to “rely on a careful analysis to answer the following questions, and ignore any intuition or ‘gut instincts’ that might arise”. Participants in the intuitive condition were instructed to “use your gut feelings or intuition to respond to the following questions, rely on your first thought, and avoid thinking too much about it” (see Appendix C for the full instruction for the thinking style conditions).

Next, participants were presented with the same choice options as in the first phase, and now responded to the following choice question: “If you were limited to these two options, how likely would you choose one option over the other?” Again, participants indicated their responses using a 100-point slider, by sliding the bar in the middle of the slider toward their choice. The score of 0 indicated that they would definitely choose Option A, and the score of 100 indicated that they would definitely choose Option B (see Appendix C for the full choice instruction).

Finally, participants received a 5-item measure to check the validity of the manipulation (e.g., “I chose the option that felt right to me”, adapted from Dane, Baer, Pratt, & Oldham, 2011; Zhu, Ritter, Müller, & Dijksterhuis, 2017), indicating the extent to which they use deliberative or intuitive thinking when completing the choice task on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree, α = .79). Higher averaged scores indicated the use of more intuitive thinking style and lower averaged scores indicated the use of more deliberative thinking style. The duration of participants’ completion of the choice task was also recorded as an indirect measure of the manipulation effectiveness. We reasoned that participants would complete the task faster in the intuitive condition than in the deliberative condition.

A self-reported measure to identify careless participants (i.e., “In your honest opinion, should we use your data?”; Meade & Craig, 2012), and a short debriefing text about the study were presented at the end of the study.

Data Analysis

In total, the dataset consisted of 2100 observations, derived from responses of 140 participants to 15 pairs of options. Data were checked for outliers and multicollinearity prior to analysis. Inspection of the data revealed that there was an error in programming one pair of the option (i.e. pair number 14), and it was excluded from the analyses. After doing so, the dataset used for the analyses consisted of 1960 observations. Supplementary data can be found at the OSF (https://osf.io/vp6td/).

Given that the 14 pairs of options (i.e., scenarios) were measured within participants (i.e., P_num), a linear mixed-effects model approach was used to analyze the following model:

This model estimates both fixed effects (i.e., the effect of the predictors: happiness and thinking condition, and their interaction, on the dependent variable: choices) and random effects (i.e., taking into account individual differences in participants’ response tendencies, and possible differences in scenarios). The data analysis was conducted in R (version 3.4.4, R Core Team, 2018), using the mixed() function of the afex package (version 0.20–2, Singmann, Bolker, Westfall, & Aust, 2018). We followed the advice of Barr, Levy, Scheepers, and Tily (2013) to use a maximal random-effects structure for models where possible. The structure included by-participants and by-scenarios random intercepts and random slopes for the predictors varying within-participants and within-scenarios (i.e., anticipated happiness and conditions), as well as all correlation terms among the random effects. To measure the differences between intuitive and deliberative conditions, we used the sum contrasts (and accordingly Type III Sums of Squares) with deliberative condition as the reference category. To determine p-values of overall effects we used the conditional F tests with Kenward-Roger correction of degrees-of-freedom, as implemented in the Anova() function from the package car (version 2.1–6; Fox & Weisberg, 2018).

Using a similar linear mixed-effects model, we tested the moderation of individuals’ preference for intuitive and deliberative thinking by entering PID-I scores and PID-D scores separately, replacing the conditions part in the model.

Results

Manipulation Check

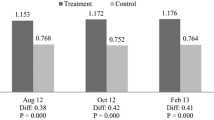

To examine the effectiveness of the manipulation instruction of intuitive and deliberative thinking, we conducted an independent sample t-test with thinking style as the grouping variable and the mean of participants’ scores on the manipulation check as the test variable. Results show that participants reported more intuitive thinking when completing the task in the intuitive condition, M = 5.09, SD = 0.78, than participants in the deliberative thinking condition, M = 3.37, SD = 0.90, t(1936.7) = 45.29, p < .001. When we tested the effect of condition on the time spent to complete the task using a Mann-Whitney test, we found that participants in the intuitive condition, Mdn = 4.9 s per scenario, spent less amount of time on making decisions as compared to participants in the deliberative condition, Mdn = 5.2 s per scenario, U = 441,449.5, p = .002. These results indicated that participants both reported more intuitive thinking when completing the task in the intuitive condition, and indeed made faster decisions, than participants in the deliberative thinking condition.

The Effect of Anticipated Happiness and Thinking Styles on Choice

The linear mixed-effects model testing, as described in the data analysis section, revealed a significant main effect of anticipated happiness on choice, F(1, 22.42) = 392.41, p < .001. Consistent with hypothesis 1, the more participants believed that an option would contribute to their happiness, the more likely they were to choose the option.

Contrary to hypothesis 2a, the relationship between anticipated happiness and choice was not significantly different in the intuitive condition and in the deliberative condition, F(1, 126.16) = 0.04, p = .84. For completeness, we report that the main effect of thinking style on choice was not significant, F(1, 137.73) = 0.51, p = .48, but note that this main effect is arbitrary (i.e., it simply indicates whether or not condition is associated with being more likely to choose the left or right options). Similarly, contrary to hypothesis 2b, we did not find support for the moderation of the measured preference of thinking styles (i.e., PID-I, F(1, 111.44) = 1.19, p = .27, and PID-D, F(1, 121.45) = 1.33, p = .25). Thus, irrespective of experimentally manipulated or self-reported decision-making style, participants based their choices on the anticipated happiness of the choice options.

Discussion

Do people choose based on what they believe makes them happy? And if so, does the extent to which people do so depend on their (manipulated or preferred) intuitive versus deliberative thinking style? The present study replicates the finding of Benjamin et al. (2012), demonstrating that when making choices, participants were inclined to choose the option that they believed would bring them more happiness (i.e., the option with the highest level of anticipated happiness). Interestingly, however, we found no evidence that this tendency was moderated by making choices in an either intuitive or deliberative mindset (in fact, as can be read in the online resource, the anticipated happiness effect on choice was not moderated by any of the factors that we measured additionally, including the level of happiness of the participant, materialistic values, or tendency to pursue happiness). In short, the current findings indicate that people’s choices are directed by the extent to which they expect that the choices will bring more happiness, irrespective of how the choices are made.

The current research findings provide additional evidence for the literature on emotion-based choice (Mellers et al., 1999). Previous research suggests that decisions are influenced by anticipated specific emotions, like regret or disappointment that might result from a decision (e.g., Abraham & Sheeran, 2004; Richard, van der Pligt, & de Vries, 1996; Zeelenberg & Pieters, 2004). In addition to such previous findings, our results suggest that decisions are influenced by anticipated happiness. An explanation for our findings could be derived from the subjective expected pleasure theory (Mellers et al., 1999; Mellers & Mcgraw, 2001). According to this theory, people often make an estimation of the pleasure or pain a future action will bring. We reason that, in our study, when participants were presented with the hypothetical life events, they anticipated the pleasure or the pain they would experience as a result of choosing each of the available options, which gives them a general sense of how happy or unhappy choosing a certain option would make them. They then chose the option they thought would maximize happiness.

The present findings seem to further underline the importance of happiness in people’s lives. That is, the findings suggest that people do make choices based on what they believe would make them more happy (i.e., anticipated happiness). For many if not most people, the desire to be happy is more important than other goals (Diener, 2000; Myers, 2000), and this striving for happiness is supported by many research findings suggesting that people can actually do something to become happier (Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013; Tkach & Lyubomirsky, 2006). Anticipating the level of happiness a certain choice would bring, and choosing based on this estimation, is potentially an effective strategy that people use to optimize happiness levels.

Importantly, in the current research, we did not find that intuitive or deliberative thinking style (nor any other factors; see online resource), weakened the link between anticipated happiness and choice. This raising the interesting question: what factors possibly would cause people to make choices that do not make them happy? First, although not examined here, one important factor may be social norms that may undermine the effect of anticipated happiness on choice. In the current research, participants made their choices arguably without being influenced by social norms. They made their choices online and anonymous, and the choices were hypothetical. However, in real-life decisions, people may consider social norms to a varying degree when making decisions. In other words, they may choose based on what a social norm dictates rather than on what makes them happy. As an interesting example, research demonstrates that people choose to stay in a romantic relationship that makes them unhappy because they believe it is the norm to stay in the relationship, and leaving the relationship may result in social disapproval (e.g., Etcheverry & Agnew, 2004). Thus, future research may examine whether social norms moderates the relationship between anticipated happiness and choice.

Several scholars have suggested that the relationship between the style of thinking and decision-making is stronger when the attributes of the decision task matches the characteristics of the style of thinking (Dijksterhuis & Nordgren, 2006; Epstein, 1994; Wilson & Schooler, 1991). To give an example, Inbar, Cone, and Gilovich (2010) demonstrated that the nature of the decision-making task induces people to use either deliberative or intuitive processing styles. For example, when making a preferential choice (i.e., choosing between different options, as was the case in the present study), people tend to use an intuitive decision-making style, whereas people tend to use a deliberative style if a choice is perceived as objectively evaluable (i.e., a decision that is evaluated against an objective standard). An interesting topic to investigate in the future is whether the association between anticipated happiness and choice may be weaker in decision-making tasks that require more deliberation.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the present findings. First, we presented hypothetical choice options to the participants and asked them to make hypothetical choices, so that there were no real consequences of their choices. This may have discouraged participants to be strongly engaged in the task, and results may change if participants were presented with real options (i.e., choices that are relevant to their personal life or that result in real consequences). We acknowledge that this is an important limitation, as perhaps the anticipated happiness effect that we find here is inflated as compared to the role of anticipated happiness in real life. As noted above, in real life concerns like norms should become more salient when the choices have actual consequences, and can be perceived and ‘judged’ by others. Future research should replicate the present findings for actual real-life choices, and examine potential moderators of the role of anticipated happiness in making actual choices.

Second, even though participants in the deliberative (versus intuitive) condition did report that they engaged in more deliberation, and indeed took more time to make a decision, probably this still does not reflect the amount of deliberation that people engage in when making a choice in real life. It is likely that more deliberative thinking is required to overwrite the effects of anticipated happiness on choice, as we predicted. Thus, even though that we found converging (null) evidence that both individual difference measures and an experimental manipulation did not affect the role of happiness in decision-making at all, future research needs to try stronger manipulations of thinking style, in combination with actual rather than hypothetical choices.

Finally, participants were instructed explicitly to reflect on the anticipated happiness of a choice option, which in itself may have influenced their subsequent choice. For example, the anticipated happiness question may have served as a ‘prime’ for the choice. With regard to this point, our study arguably is a methodological improvement to the Benjamin et al. (2012) study, in which participants responded to the anticipated happiness, and to the choice question right after each other, whereas in our study there was at least five days in between the anticipated happiness question and the choice. Still, we do not know to what extent in real life people spontaneously make an estimation of the happiness outcomes of a choice before they actually make a choice.

Conclusion

The present research found the effect of anticipated happiness on choice, irrespective of participants’ way and preference of thinking (and irrespective of subjective happiness, materialistic value, and pursuit of happiness; as shown in the online supporting materials). In other words, we did not find support that any seemingly relevant personality characteristic, nor an induced decision style, weakened (nor strengthened) the influence of anticipated happiness on the choices that participants made. Although these findings should be considered in light of some limitations, they are consistent with the general idea that happiness is a prominent driver in the lives of most people. It is our hope that the present results form a springboard to further examine this topic.

Data Availability

The raw data and the R script for analyses are available at a public repository website (https://osf.io/vp6td/).

Notes

In this manuscript, the term “anticipated happiness” was used to represent “expected contribution to happiness” in the pre-registered plan because the term is more commonly used in other literature.

For exploratory reasons, we also measured several potential moderating variables on the relationship between anticipated happiness and choice, namely: subjective happiness, materialistic value orientation, and the pursuit of happiness. We reported the analyses and results of these variables in the online resource.

References

Abraham, C., & Sheeran, P. (2004). Deciding to exercise: The role of anticipated regret. British Journal of Health Psychology, 9(2), 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910704773891096.

Bagozzi, R. P., Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., & Flavián, C. (2016). The role of anticipated emotions in purchase intentions. Psychology & Marketing, 33(8), 629–645. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20905.

Barr, D. J., Levy, R., Scheepers, C., & Tily, H. J. (2013). Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language, 68(3), 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001.

Benjamin, D. J., Heffetz, O., Kimball, M. S., & Rees-Jones, A. (2012). What do you think would make you happier? What do you think you would choose? American Economic Review, 102(5), 2083–2110. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.102.5.2083.

Betsch, C. (2004). Praferenz fur intuition und deliberation. Inventar zur erfassung von affekt- und kognitionsbasiertem entscheiden [Preference for intuition and deliberation (PID): An inventory for assessing affect- and cognition-based decision-making]. Zeitschrift Für Differentielle Und Diagnostische Psychologie, 25(4), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1024/0170-1789.25.4.179.

Betsch, C., & Kunz, J. J. (2008). Individual strategy preferences and decisional fit. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 21(5), 532–555. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.600.

Chaiken, S., & Trope, Y. (1999). Dual-process theories in social psychology. New York: The Guilford Press.

Dane, E., Baer, M., Pratt, M. G., & Oldham, G. R. (2011). Rational versus intuitive problem solving: How thinking “off the beaten path” can stimulate creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 5(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017698.

de Vries, M., Fagerlin, A., Witteman, H. O., & Scherer, L. D. (2013). Combining deliberation and intuition in patient decision support. Patient Education and Counseling, 91(2), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.016.

de Vries, M., Holland, R. W., & Witteman, C. L. M. (2008). Fitting decisions: Mood and intuitive versus deliberative decision strategies. Cognition & Emotion, 22(5), 931–943. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930701552580.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34.

Diener, E., & Fujita, F. (1995). Resources, personal strivings, and subjective well-being: A nomothetic and idiographic approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(5), 926–935. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.5.926.

Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2004). Are Scandinavians happier than Asians? Issues in comparing nations on subjective well-being. In F. Columbus (Ed.), Asian economic and political issues (pp. 1–25). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00415.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of Progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Dijksterhuis, A., & Nordgren, L. F. (2006). A theory of unconscious thought. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(2), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00007.x.

Dijksterhuis, A., & van Olden, Z. (2006). On the benefits of thinking unconsciously: Unconscious thought can increase post-choice satisfaction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(5), 627–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.10.008.

Dundes, L., Cho, E., & Kwak, S. (2009). The duty to succeed: Honor versus happiness in college and career choices of east Asian students in the United States. Pastoral Care in Education, 27(2), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643940902898960.

Epstein, S. (1994). Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamic unconscious. American Psychologist, 49(8), 709–724. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.49.8.709.

Etcheverry, P. E., & Agnew, C. R. (2004). Subjective norms and the prediction of romantic relationship state and fate. Personal Relationships, 11, 409–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00090.x.

Evans, J. S. B. T. (2003). In two minds: Dual-process accounts of reasoning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(10), 454–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2003.08.012.

Evans, J. S. B. T. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629.

Evans, J. S. B. T. (2010). Intuition and reasoning: A dual-process perspective. Psychological Inquiry, 21(4), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2010.521057.

Fox, J., & Weisberg, S. (2018). An {R} companion to applied regression (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. Retrieved from http://socserv.socsci.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion.

Howell, K. H., Coffey, J. K., Fosco, G. M., Kracke, K., Nelson, S. K., Rothman, E. F., & Grych, J. H. (2016). Seven reasons to invest in well-being. Psychology of Violence, 6(1), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000019.

Howell, R. T., & Guevara, D. A. (2013). Buying happiness: Differential consumption experiences for material and experiential purchases. In A. M. Columbus (Ed.), Advances in psychology research. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc..

Hsee, C. K., & Kunreuther, H. C. (2000). The affection effect in insurance decisions. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 20(2), 141–159.

Inbar, Y., Cone, J., & Gilovich, T. (2010). People’s intuitions about intuitive insight and intuitive choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(2), 232–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020215.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kahneman, D., & Frederick, S. (2012). Representativeness revisited: Attribute substitution in intuitive judgment. Heuristics and Biases. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511808098.004.

King, L. A., & Broyles, S. J. (1997). Wishes, gender, personality, and well-being. Journal of Personality, 65(1), 49–76. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00529.x.

King, L. A., & Napa, C. K. (1998). What makes a life good? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.156.

Kong, D. T., Tuncel, E., & Parks, J. M. (2011). Anticipating happiness in a future negotiation: Anticipated happiness, propensity to initiate a negotiation, and individual outcomes. Negotation and Conflict Management Research, 4(3), 219–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-4716.2011.00081.x.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Layous, K. (2013). How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(1), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412469809.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111.

Meade, A. W., & Craig, S. B. (2012). Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 437–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028085.

Mellers, B. A., & Mcgraw, A. P. (2001). Anticipated emotions as guides to choice. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(6), 210–215.

Mellers, B. A., Schwartz, A., & Ritov, I. (1999). Emotion-based choice. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 128(3), 332–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.128.3.332.

Messick, S. (1976). Personality consistencies in cognition and creativity. In S. Messick (Ed.), Individuality in learning (pp. 261–293). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mogilner, C. (2010). The pursuit of happiness : Time, money, and social connection. Psychological Science, 21(9), 1348–1354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610380696.

Myers, D. G. (2000). The funds, friends, and faith of happy people. American Psychologist, 55(1), 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.56.

Phillips, W. J., Fletcher, J. M., Marks, A. D. G., & Hine, D. W. (2016). Thinking styles and decision-making: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 142(3), 260–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000027.

Prelec, D., & Herrnstein, R. (1991). Preferences or principles: Alternative guidelines for choice. In R. J. Zeckhauser (Ed.), Strategy and choice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

R Core Team (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.r-project.org/.

Richard, R., van der Pligt, J., & de Vries, N. (1996). Anticipated affect and behavioral choice. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 18(2), 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp1802_1.

Rottenstreich, Y., & Hsee, C. K. (2001). Money, kisses, and electric shock: On the affective psychology of risk. Psychological Science, 12(3), 185–190.

Simonson, I. (1990). The effect of purchase quantity and timing on variety-seeking behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 27(2), 150–162. https://doi.org/10.2307/3172842.

Singmann, H., Bolker, B., Westfall, J., & Aust, F. (2018). Afex: Analysis of factorial experiments. R package version 0.20–22. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/package=afex.

Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2007). The affect heuristic. European Journal of Operational Research, 177(3), 1333–1352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2005.04.006.

Tkach, C., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How do people pursue happiness?: Relating personality, happiness-increasing strategies, and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 183–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-005-4754-1.

Westfall, J. (2016). PANGEA: Power analysis for general Anova designs. Retrieved from http://jakewestfall.org/publications/pangea.pdf.

Wilson, T. D., Lisle, D. J., Schooler, J. W., Hodges, S. D., Klaaren, K. J., & LaFleur, S. J. (1993). Introspecting about reasons can reduce post-choice satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19(3), 331–339.

Wilson, T. D., & Schooler, J. W. (1991). Thinking too much: Introspection can reduce the quality of preferences and decisions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(2), 181–192.

Zeelenberg, M., & Pieters, R. (2004). Beyond valence in customer dissatisfaction: A review and new findings on behavioral responses to regret and disappointment in failed services. Journal of Business Research, 57(4), 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00278-3.

Zhu, Y., Ritter, S. M., Müller, B. C. N., & Dijksterhuis, A. (2017). Creativity: Intuitive processing outperforms deliberative processing in creative idea selection. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 73(August), 180–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.06.009.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Julian Quandt for his contributions to this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were following the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (The Ethics Committee, Faculty of Social Sciences, Radboud University, reference number 18 U.004781) and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(PDF 484 kb)

Appendices

Appendix A. Sample Size Calculation (information available at https://osf.io/63f2j)

A power analysis using PANGEA v0.2 (Westfall, 2016, p. 23) an open-source, web-based power application, with the following parameters (see Table 1 below) shows that a minimum of 120 participants is required in this study. Taking into account that we will need to exclude some participants that did not return for the second phase of data collection and failed to pass the self-report question to identify careless participants, which from our own and other colleagues’ previous online study experience happens in approximately 1/4 of the participants, we aim to recruit 150 participants.

Appendix B. Pairs of Choice Options

The table below shows 6 life domains (i.e. romantic relationship, health, leisure, money, friendship, and job) that we presented. The pairs of options were developed by pairing the domain to one another, resulting in 15 pairs of options (second column). The next columns show the exact wordings of the pairs of options related to the intended domain.

Appendix C. Examples of the Tasks

Phase 1: Anticipated Happiness Question

Instructions:

You will be presented with a question followed by a pair of options on the screen. Each option describes the choices you could have in daily life. Below the pair of options, there is a slider, as you can see below. Please indicate your answer to the question by sliding the bar on the slider toward your choice, such that the more likely you choose one option, the closer the bar gets to the option.

Item 1.

Between these two options, how much do you think one option would contribute to your happiness relative to the other one?

Phase 2: Choice Question in Intuitive Condition

Instructions:

You will be presented with a question followed by a pair of options on the screen. Each option describes the choices you could have in daily life. Below the pair of options, there is a slider, as you can see below. Please indicate your answer to the question by sliding the bar on the slider toward your choice, such that the more likely you choose one option, the closer the bar gets to the option.

Furthermore, we are interested in why intuitive thinkers are more successful and we want to see how they make judgments. There is clear evidence that people who adopt an intuitive approach to thinking are excelled in various aspects of life.

Therefore, please use your gut feelings and intuition when you make choices as instructed previously, relying on your first thought, and avoid thinking too much about it.

Item 1.

Based on your intuition, if you were limited to these two options, how likely would you choose one option over the other?

Phase 2: Choice Question in Deliberative Condition

Instructions:

You will be presented with a question followed by a pair of options on the screen. Each option describes the choices you could have in daily life. Below the pair of options, there is a slider, as you can see below. Please indicate your answer to the question by sliding the bar on the slider toward your choice, such that the more likely you choose one option, the closer the bar gets to the option.

Furthermore, we are interested in why deliberative thinkers are more successful and we want to see how they make judgments. There is clear evidence that people who adopt a deliberative approach to thinking are excelled in various aspects of life.

Therefore, please rely on a careful analysis when you make choices as instructed previously, and ignore any intuition or ‘gut instincts’ that might arise.

Item 1.

Based on your careful analysis, if you were limited to these two options, how likely would you choose one option over the other?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumalasari, A.D., Karremans, J.C. & Dijksterhuis, A. Do people choose happiness? Anticipated happiness affects both intuitive and deliberative decision-making. Curr Psychol 41, 6500–6510 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01144-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01144-x