Abstract

This study investigated whether relationship satisfaction mediates the association between own and perceived partner mate-retention strategies and commitment. One hundred and fifty individuals (Mage = 23.87, SDage = 7.28; 78.7% women) in a committed relationship participated in this study. We found an association between perceived partner mate-retention strategies and commitment and that relationship satisfaction mediated this link. Similarly, we found that relationship satisfaction also mediated the association between individuals’ own cost-inflicting strategies and commitment. Specifically, perceived partner benefit-provisioning strategies are positively associated with commitment through increased relationship satisfaction and, conversely, both perceived partner and own cost-inflicting strategies are negatively associated with commitment through decreased relationship satisfaction. Additionally, we observed that relationship satisfaction moderated the association between perceived partner cost-inflicting strategies and participants’ own frequency of cost-inflicting strategies. That is, participants’ cost inflicting strategies are associated with their partner’s cost inflicting strategies, such that this association is stronger among individuals with higher relationship satisfaction. The current research extends previous findings by demonstrating that the association between perceived partner and own mate-retention strategies and commitment is mediated by relationship satisfaction. Additionally, we showed that an individual’s expression of mate retention is associated with their perception of the strategies displayed by their partner, which also depends on relationship satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Long-term relationships evolved as a solution to solve multiple adaptive problemsFootnote 1 such as acquiring sufficient parental investment, acquiring different types of investment, and maintaining female fecundity (i.e. capacity for reproduction; Salmon 2017). The game-theoretic model (Conroy-Beam et al. 2015) proposes that long-term relationships can be understood as public goods games, in which players invest resources into a shared pool. According to this model, both partners independently invest their resources in the relationship that returns fitnessFootnote 2 dividends to both. For instance, partners invest in shared pools such as shared financial resources, shared social networks, and shared offspring. This explains why individuals put considerable effort into selecting and attracting a valuable partner, and after having established a romantic relationship with the loved one, significant effort is still necessary to ensure that the relationship will endure and therefore, all the resources invested in the relationship will pay off.

The mechanisms designed to guard a partner, prevent potential infidelity, and, therefore, make a relationship last are called mate-retention strategies (Buss 1988). Such behaviours reflect one’s attempts to restrict and regulate partner sexual autonomy and are hypothesised to be an adaptive solution for the problem of intrasexual competition for mates. Ancestral men and women who used such strategies were more reproductively successful because they were better at avoiding threats from rivals and at preventing partner infidelity (Yong and Li 2018). While there are studies exploring predictors of mate retention, fewer studies have focused on the outcomes of such strategies to identify, for example, which tactics work best to protect a romantic relationship. Relationship satisfaction and commitment are indicators of the success of a relationship, and both predict relationship dissolution (Le et al. 2010). Although it has been hypothesised that benefit-provisioning strategies operate by enhancing relationship satisfaction, which, in turn, enhances commitment to the relationship (Albert and Arnocky 2016; Buss 1988; Campbell and Ellis 2005), this assumption lacks stronger empirical support. In this regard, because individuals may not be aware of some of their partner’s mate-retention behaviours, the individual perception of partner mate retention may be more determinant to relationship satisfaction and commitment than the actual mate-retention behaviours displayed by the partner (see Montoya et al. 2008). Therefore, this study aimed to explore a potential indirect effect of perceived mate retention of the partner on commitment through relationship satisfaction, using an evolutionary perspective. In the following sections, we discuss potential empirical links between these variables.

Partner Mate Retention, Relationship Satisfaction and Commitment

Mate-retention strategies encompass two different broad categories. The first category operates by inflicting costs on the partner, such as monopolising the partner’s time and jealousy induction. These tactics function to reduce partner self-esteem by making the partner feel unworthy and, therefore, reducing their probability of leaving the relationship (Albert and Arnocky 2016). Conversely, benefit-provisioning strategies, the second broad category of mate-retention tactics, involve strategies such as display of love and care and own appearance enhancement, and are hypothesised to increase partner commitment to the relationship (Buss 1988). Factors such as age and relationship length have been found to be negatively associated with the display of mate-retention strategies, and men have been found to engage in such strategies more often than women (Atari et al. 2017). Regarding the association between mate retention and commitment, researchers have documented that those individuals who are more committed to their relationships tend to devote more effort to mate retention (Buss et al. 2008). Specifically, individuals in more committed relationships display higher levels of benefit-provisioning strategies, whereas those in less committed relationships more often report higher levels of jealousy-evoking tactics, a subtype of cost-inflicting strategies (Miguel and Buss 2011). Similarly, husbands who perceive low commitment in their wives tend to report higher levels of mate retention (French et al. 2017). Individuals that perceive their partners to have higher mate value than themselves, a factor that could relate to higher commitment, also engage in both benefit-provisioning and cost-inflicting mate-retention strategies more frequently (Sela et al. 2017). However, the influence of different types of mate-retention strategies displayed by the partner on an individual’s own commitment to the relationship needs further examination, particularly when it comes to perceived mate-retention strategies displayed by the partner.

Because previous researchers have argued that benefit-provisioning mate-retention strategies function to enhance partner commitment to the relationship (Albert and Arnocky 2016; Barbaro et al. 2015), the association between perceived partner benefit-provisioning strategies and commitment should be positive. Indeed, individuals’ perception of their partners’ relationship maintenance behaviours (e.g., praising the partner for their achievements, spending time with the partner) is reported to be positively associated with individuals’ own commitment with the relationship (Ogolsky 2009). Researchers exploring the related topic of relationship investment have also demonstrated that individuals who perceive their partners to have invested more in the relationship reported higher levels of commitment to the relationship (Joel et al. 2013). On the other hand, the association between perception of a partner’s cost-inflicting strategies and an individual’s commitment is expected to be negative because such strategies operate by manipulating or coercing a partner into staying in the relationship (Conlon 2019).

To better understand the association between partner mate retention and commitment, it is important to consider the Investment Model (Rusbult 1983; Rusbult and Van Lange 2003), which is underpinned by interdependence theory (Kelley and Thibaut 1978), and used to study relationship satisfaction and commitment. According to this model, individuals should be more satisfied with their relationships if the relationship provides high rewards, low costs and exceeds the individual’s generalised expectation (Rusbult and Farrell 1983). In turn, high relationship satisfaction should enhance an individual’s commitment to the relationship. In fact, relationship satisfaction is one of the main predictors of commitment to the relationship (Rhoades et al. 2010). Although relationship satisfaction and commitment are correlated, they are two different constructs and influence relationship outcomes differently. For example, a meta-analysis using data from 37,771 participants in 137 studies over 30 years demonstrated that commitment is amongst the strongest negative predictors of relationship dissolution, while relationship satisfaction is a modest negative predictor of relationship dissolution (Le et al. 2010). Therefore, for a more comprehensive understanding of relationship stability, it is important to differentiate between the two constructs.

Consistent with the investment model, evolutionary psychologists theorise that relationship satisfaction or dissatisfaction is an evolved psychological device that facilitates monitoring the overall costs and benefits associated with romantic relationships (Shackelford and Buss 1997). Indeed, individuals who perceive their partners to use cost-inflicting strategies such as emotional manipulation and jealousy induction reported lower satisfaction with their relationship (Shackelford and Buss 2000). Similarly, Dandurand and Lafontaine (2014) demonstrated that an individual’s perception of their partner’s cognitive jealousy (worries about partner infidelity) predicted couple relationship satisfaction negatively. However, an individual’s perception of their partner’s expression of emotional jealousy (emotional reactions to potential threats) positively affected relationship satisfaction, potentially because participants understood the partner’s emotional jealousy as an expression of their investment in the relationship. Thus, relationship satisfaction would influence commitment to the relationship. Following the investment model, we propose that the association between partner mate-retention strategies and commitment is mediated by relationship satisfaction. In fact, a study with interracial married couples demonstrated that relationship satisfaction mediates the association between relationship maintenance communication (e.g., giving advice, use of social networks) and commitment (Dainton 2015). Although this study examined maintenance communication rather than mate-retention strategies, it showed certain behaviours performed by the partner such as infidelity, for example, influence relationship satisfaction negatively, reducing commitment to the relationship.

If on one hand, perceived partner mate-retention efforts are associated with an individual’s relationship satisfaction and commitment, on the other hand, perceived partner mate retention may also influence the individual’s own mate-retention strategies. This is because romantic partners tend to reciprocate both positive and negative affects and behaviours, including care, respect, and hostility (Gaines 1996; Gleason et al. 2003). Indeed, individuals’ use of mate retention is strongly associated with their partners’ displays of mate retention, such that individuals tend to reciprocate both cost-inflicting and benefit-provisioning strategies (Shackelford et al. 2005; Welling et al. 2012). The principle of homogamy (positive assortative mating; see Valentova et al. 2017) suggests that individuals tend to mate with partners that are similar to themselves in several attributes from perceived attractiveness (Little et al. 2006) to personality traits (Kardum et al. 2017). Thus, homogamy is also likely to explain a similar use of mate-retention strategies between partners.

However, the association between romantic partners’ use of mate-retention strategies may vary according to the level of relationship satisfaction. Relationship satisfaction works as an important mechanism for the performance of individuals’ own mate-retention strategies (Conroy-Beam et al. 2015) because, although mate-retention strategies provide many benefits, such as preventing infidelity and preserving a relationship, some costs are also associated with the performance of mate retention (Danel et al. 2017). Tactics such as monopolising partner time and buying gifts require time, effort, and financial resources. Therefore, individuals need strategies to monitor whether their partner is worth such investment by assessing relationship quality (Shackelford and Buss 1997). As such, low relationship satisfaction would motivate individuals to end their relationship by reducing commitment, whereas high relationship satisfaction would motivate individuals to engage in behaviours to preserve the partnership (Conroy-Beam et al. 2015). We expect that individuals who are more satisfied with their relationships would increase mate retention efforts rather than merely reciprocating their partners’ mate-retention tactics. Thus, a secondary aim of this study is to explore whether relationship satisfaction also affects the association between perceived partner mate retention and an individual’s own mate-retention strategies.

The Present Study

The primary function of mate-retention strategies is to preserve a romantic relationship by preventing partner infidelity (Buss 1988). Whilst cost-inflicting strategies may help to prevent potential infidelity, they also pose a risk to the relationship as they may decrease partner commitment to the relationship, whereas benefit-provisioning strategies seem to increase partner commitment (Albert and Arnocky 2016; Barbaro et al. 2015). Relationship satisfaction is also associated with partner mate-retention strategies (Shackelford and Buss 2000). Because individuals track the costs versus benefits of a long-term relationship through evolved mechanisms such as relationship satisfaction (Shackelford and Buss 1997), that, in turn, influences commitment (Rusbult and Farrell 1983), we propose that perceived partner mate-retention strategies predict commitment through relationship satisfaction. Specifically, we hypothesise that:

-

Hypothesis 1a. Partner mate retention strategies are associated with individual’s commitment to the relationship.

-

Hypothesis 1b. Relationship satisfaction mediates the association between perceived partner mate-retention strategies and commitment.

Additionally, individuals who display higher levels of benefit-provisioning strategies tend to be more committed to their relationships, whereas those that more often display cost-inflicting strategies tend to be less committed to their relationships (Miguel and Buss 2011). Given the previously discussed functions of relationship satisfaction, we also expect that an individual’s own mate-retention strategies are associated with commitment through relationship satisfaction. Specifically, we hypothesise that:

-

Hypothesis 2. Relationship satisfaction mediates the association between own mate-retention strategies and commitment.

Furthermore, individuals reciprocate their partners’ cost-inflicting and benefit-provisioning mate-retention strategies (Shackelford et al. 2005; Welling et al. 2012). However, because greater relationship satisfaction motivates increased investment in a romantic relationship (Conroy-Beam et al. 2016), we expect this association to vary according to individuals’ relationship satisfaction. Therefore, we examined whether relationship satisfaction moderates the association between perceived partner mate-retention strategies and individuals’ own displays of mate retention. Specifically, we hypothesise that:

-

Hypothesis 3. Relationship satisfaction moderates the association between perceived partner mate-retention strategies and individual mate retention strategies.

Methods

Participants

One hundred and fifty people that were in a heterosexual committed relationship participated in this study (78.7% were women), aged between 18 and 50 years old (M = 23.87, SD = 7.28). Most participants were European (47.5%), North American (35.3%), Asian (11.4%), and South American and African (5.8%). Most participants were dating (67.3%; married = 18.7%; engaged = 8.7%; cohabiting = 5.3%) in a relationship for at least two months (less than a year = 33.3%; between 2 and 5 years = 25.3%; between one and two years = 21.3%; over 5 years = 20%).

Materials

Self-Reported and Perceived Mate Retention of the Partner

The Mate Retention Inventory (Short-Form, MRI-SF, Buss et al. 2008) was used to assess individuals’ own mate-retention strategies and perceived mate retention of their partners. The MRI-SF is composed of 38 items that were used to assess two broad mate-retention categories: cost-inflicting strategies (e.g., snooped through my partner’s personal belongings; insisted that my partner spend all her/his free time with me; showed interest in another woman/man to make my partner angry), and benefit-provisioning strategies (e.g., bought my partner an expensive gift; displayed greater affection for my partner; bragged about my partner to other men/women). Participants indicated how often they performed each behaviour within the past year, using a scale varying from 0 (never) to 3 (often performed this act). Higher scores on own cost-inflicting (M = 1.55, SD = .37, α = .81) and benefit-provisioning strategies (M = 2.66, SD = .47, α = .82), and perceived partner cost-inflicting (M = 1.59, SD = .46, α = .87) and benefit-provisioning strategies (M = 2.66, SD = .51, α = .84), reveal higher frequency of mate-retention strategies.

Couples Satisfaction Index (Funk and Rogge 2007)

This instrument is composed of 32 items designed to measure satisfaction in a romantic relationship. Participants indicated to what extent each of the items represented how they felt in their relationship (e.g. I still feel a strong connection with my partner; My relationship with my partner makes me happy). The statements were answered on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = not true at all to 6 = completely true), apart from the first one that is answered on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = extremely unhappy to 6 = perfect; Please indicate the degree of happiness, all things considered, of your relationship). Higher scores on this scale (M = 5.00, SD = .84, α = .95) reveal higher relationship satisfaction.

Commitment to the relationship (Rusbult et al. 1998)

Relationship commitment was assessed using a seven-item scale. Participants indicated to what extent each of the items represented how they felt in their relationship (e.g. I want our relationship to last for a very long time; It is likely that I will date someone other than my partner within the next year), using a 7-point Likert scale, varying from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Higher scores on this scale (M = 6.14, SD = 1.02, α = .84) reveal higher relationship satisfaction.

Likelihood to End the Relationship

This was measured through one question (i.e. How likely are you to end your current relationship?) answered on a 7-point Likert scale varying from 1 = extremely unlikely to 7 = extremely likely. Higher scores on this scale (M = 1.77, SD = 1.30) reveal higher likelihood to end the relationship.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through the Research Participation Scheme from the Department of Psychology, University of Bath, social media (e.g. Facebook), and research advertising websites. The study took place online on Qualtrics. Participants initially read the participant information sheet, where all the procedures involved in the study were explained, and after giving their informed consent to participate, they completed several self-report questionnaires assessing the variables of interest. At the end, participants were redirected to a debriefing page, where a more detailed description of the study was provided. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the psychology ethics committee of the University of Bath (ethical approval code: 17–218).

Results

Initially, we conducted a power analysis using G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al. 2009) to confirm that the current study’s sample size was appropriate to examine our hypotheses. The analysis demonstrated that the current study achieved a power of greater than .97 for detecting a medium size effect, which is above the recommended threshold of .80 (Cohen 1992). For completeness, all correlations between own and perceived partner mate-retention strategies, relationship satisfaction, commitment, age, sex (coded as 0 = male 1 = female), and relationship length can be found in Table 1. As displayed in Table 1, confirming Hypothesis 1a, commitment was positively associated with perceived partner benefit-provisioning strategies, but negatively correlated with perceived partner cost-inflicting strategies.

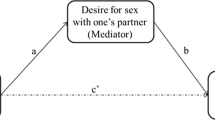

To test Hypothesis 1b, whether relationship satisfaction mediates the link between perceived partner mate retention and commitment, we conducted a mediation analysis using the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013). Because perceived partner benefit-provisioning strategies and cost-inflicting strategies are associated with relationship satisfaction and commitment differently, we conducted two separate mediation analyses, one for each type of mate retention strategy. Results from bootstrapping confidence intervals (CIs = 95%, n = 5000), controlling for age, sex and relationship length, revealed that relationship satisfaction mediated the association between partner benefit-provisioning strategies and commitment. Specifically, higher frequency of perceived partner benefit-provisioning strategies was positively associated with relationship satisfaction (b = 0.47, p < .001, 95% CI [.18, .77]), which was associated with commitment (b = 0.88, p < .001, 95% CI [.70, 1.06]), but perceived partner benefit-provisioning strategies did not directly predict commitment (b = 0.14, p = .31, 95% CI [−.13, .41]), indicating full mediation. The overall effect size of this model was small (f2 = 0.09; Cohen 1992).

Results from bootstrapping confidence intervals (CIs = 95%, n = 5000), controlling for age, sex and relationship length, also revealed that relationship satisfaction mediated the association between perceived partner cost-inflicting strategies and commitment. Specifically, higher frequency of perceived partner cost-inflicting strategies was negatively associated with relationship satisfaction (b = −0.75, p < .001, 95% CI [−1.00, −.50]), which was positively associated with commitment (b = 0.87, p < .001, 95% CI [.70, 1.04]), but perceived partner cost-inflicting strategies did not directly predict commitment (b = −0.16, p = .34, 95% CI [−.51, .18]), indicating full mediation. The overall effect size of this model was medium (f2 = 0.16; Cohen 1992). Therefore, Hypothesis 1b was confirmed.

To test Hypothesis 2, whether relationship satisfaction mediates the relationship between own mate retention and commitment, we conducted a mediation analysis. Because benefit-provisioning strategies and cost-inflicting strategies are associated with relationship satisfaction and commitment differently, we conducted two separate mediation analyses, one for each type of mate retention strategy. Results from bootstrapping confidence intervals (CIs = 95%, n = 5000), controlling for age, sex, and relationship length, revealed that relationship satisfaction mediated the association between own benefit-provisioning strategies and commitment. Specifically, higher frequency of benefit-provisioning strategies was positively associated with relationship satisfaction but did not reach statistical significance (b = 0.32, p = .07, 95% CI [−.02, .65]), which violates one of the conditions for mediation. In turn, relationship satisfaction was positively associated with commitment (b = 0.90, p < .000, 95% CI [.73, 1.057), but own benefit-provisioning strategies did not directly predict commitment (b = 0.08, p = .50, 95% CI [−.17, .35]). The indirect effect confirmed that relationship satisfaction does not mediate the association between own benefit provisioning strategies and commitment (95% CI [−.03, .58]),

Results from bootstrapping confidence intervals (CIs = 95%, n = 5000), controlling for age, sex, and relationship length, revealed that relationship satisfaction mediated the association between own cost-inflicting strategies and commitment. Specifically, higher frequency of own cost-inflicting strategies was negatively associated with relationship satisfaction (b = −0.81, p < .001, 95% CI [−1.13, −.48]), which was positively associated with commitment (b = 0.94, p < .001, 95% CI [.63, 1.12]), but own cost-inflicting strategies did not directly predict commitment (b = 0.22, p = .18, 95% CI [−.10, .55]), indicating full mediation. The overall effect size of this model was small (f2 = .04; Cohen 1992). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was confirmed only for own cost-inflicting strategies.

For completeness, a backwards regression including commitment and relationship satisfaction as predictors, and likelihood to end the relationship as the outcome variable, demonstrated that both variables predict the outcome, F(2,147) = 75.72, Adjusted R2 = .50, p < .001. However, commitment (b = −.56) was a stronger predictor than relationship satisfaction (b = −.18). This suggests that the more satisfied and committed with the relationship individuals are, the less likely they are to terminate the relationship.

To test Hypothesis 3, whether relationship satisfaction moderates the association between perceived partner mate retention and own mate retention, we conducted two moderation analyses separately for benefit-provisioning strategies and cost-inflicting strategies. Regarding own benefit-provisioning strategies, controlling for age, sex, and relationship length, the interaction between relationship satisfaction and perceived partner benefit-provisioning strategies (b = 0.07, p = .35, 95% CI [−0.08, .23]) did not predict own benefit-provisioning strategies. Therefore, relationship satisfaction did not moderate the association between partner benefit-provisioning strategies and own benefit-provisioning strategies. Results controlling for age, sex, and relationship length, revealed that the interaction between perceived partner cost-inflicting strategies and relationship satisfaction (b = .19, p < .001, 95% CI [.08, .30]) did predict own cost-inflicting strategies. As shown in Fig. 1, those individuals with high relationship satisfaction tended to engage in cost-inflicting strategies more often when they perceived their partner to engage in cost-inflicting strategies (conditional effect = .41, SE = .07, p < .001, 95% CI [.28, .54]), compared to those with low relationship satisfaction (conditional effect = .73, SE = .06, p < .001, 95% CI [.61, .85]). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was confirmed only for cost-inflicting strategies.

Discussion

This study examined the association between own and perceived partner mate retention, relationship satisfaction, and commitment. Based on the Investment Model (Rusbult 1983) and on the game-theoretic model (Conroy-Beam et al. 2015) and on previous literature (Shackelford and Buss 2000; Dainton 2015), we tested four hypotheses in this study. We anticipated that perceived partner mate-retention strategies were associated with commitment (Hypothesis 1a) and that relationship satisfaction would mediate this association (Hypothesis 1b). Similarly, we anticipated that relationship satisfaction would mediate the association between own mate retention and commitment (Hypothesis 2). We also predicted that relationship satisfaction would moderate the association between perceived partner mate-retention strategies and an individual’s own mate-retention strategies (Hypothesis 3).

Consistent with the first two Hypotheses, perceived partner mate-retention strategies were associated with individual’s commitment to the relationship (Hypothesis 1a), and relationship satisfaction mediated this association (Hypothesis 1b) as suggested by a previous study (Dainton 2015). Consistent with previous literature (Albert and Arnocky 2016; Shackelford and Buss 2000), our study found that benefit-provisioning strategies, such as appearance enhancement and expression of affection, enhance commitment to the relationship by improving relationship satisfaction. In contrast, cost-inflicting strategies, which include monopolising the partner’s time and violence and threats directed to rivals, are detrimental to relationship satisfaction, which in turn, reduces commitment (Dandurand and Lafontaine 2014).

Similarly, we found that relationship satisfaction mediates the association between individuals’ own mate-retention strategies and commitment, but only for cost-inflicting strategies (Hypothesis 2). As suggested by previous literature, we found that individuals who display positive inducements more often tend to be more committed to their relationships (Buss et al. 2008; Dainton 2015), but this association was not explained by relationship satisfaction. On the other hand, our results suggest that individuals who engage in cost-inflicting strategies more frequently tend to experience lower relationship satisfaction, which is in turn associated with lower committed to the relationship (Miguel and Buss 2010). These findings reinforce the idea that cost-inflicting strategies, either performed by the individual or the partner are linked to poorer relationship satisfaction and low commitment.

As demonstrated in this study and supported by previous research, because relationship satisfaction and commitment are strong predictors of relationship dissolution (Le et al. 2010; Rhoades et al. 2010), these findings suggest that the usage of cost-inflicting strategies may negatively influence an individual’s likelihood to stay in the relationship. Although such strategies may be useful to some extent to keep mate poachers away, for example, they may have a negative influence on the quality of the relationship, and if used too often, they may lead to relationship dissolution. On the other hand, benefit-provisioning strategies seem to be the most useful strategies to preserve a relationship by maintaining higher relationship quality, which is associated with increased commitment to the relationship.

In the current study, relationship satisfaction was also associated with individuals’ own reporting of mate-retention strategies. Specifically, those individuals who are satisfied with their relationships tend to engage more often in benefit-provisioning strategies. On the other hand, lower relationship satisfaction is associated with higher frequency of cost-inflicting strategies. These findings are consistent with evolutionary theory, supporting the idea that relationship satisfaction works as a monitor of relationship quality (Conroy-Beam et al. 2015). As shown here, individuals who are happy in their relationships are more committed to the relationship and tend to engage more often in positive mate-retention strategies.

To test our third hypothesis, we examined whether relationship satisfaction moderates the relation between participants’ reporting of their partners’ mate-retention strategies and their own use of mate retention. We found that when individuals perceive their partners to engage more often in benefit-provisioning strategies, they tended to respond by engaging in similar positive strategies too. However, this association does not vary according to the level of relationship satisfaction. Thus, regardless of how happy individuals are with their relationships, if their partners treat them well, they will reciprocate, consistent with previous findings (Shackelford et al. 2005; Welling et al. 2012). It may also be the case that, consistent with homogamy, individuals tend to mate with individuals that perform similar mate-retention strategies to theirs.

Similarly, those participants who perceived their partners to conceal them and monopolise their time, for example, were more likely to engage in such cost-inflicting strategies themselves. However, relationship satisfaction altered this association, such that this association was stronger among individuals with higher relationship satisfaction. Thus, if individuals perceive that their partners are investing more in the relationship even if they do this by using cost-inflicting strategies, they tend to respond in a similar way by increasing their mate-retention efforts, especially if they perceive the quality of the relationship to be high. These findings also give partial support to the assumption that relationship satisfaction monitors relationship quality and as such, results in higher investment in the relationship (Conroy-Beam et al. 2016; Shackelford and Buss 1997). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was confirmed only for cost-inflicting strategies, but not for benefit-provisioning strategies.

One limitation of this study is that the sex-imbalanced sample that did not allow for comparisons across sexes. Future research could investigate how the patterns found here vary across sexes because men and women use mate-retention strategies differently, such that men tend to engage more often in strategies such as resource display than women do, whereas women tend to engage more often in strategies such as appearance enhancement in comparison to men (Albert and Arnocky 2016). A second limitation is the non-probability and convenience nature (i.e., non-random internet recruitment so participants are self-selected) of the sample, which can limit the generalisability of our findings. Another limitation of note is that we relied on people’s report of their partners’ behaviour, and we have no way of identifying the extent to which their perception corresponds to reality. However, previous literature has demonstrated that individuals’ self-reports of their mate-retention behaviours are congruent with their partners’ reports of their mate-retention behaviours, demonstrating that individuals can provide reliable accounts of their partners’ mate-retention strategies (Shackelford et al. 2005). Moreover, people’s perceptions of their partners’ behaviour may be more important than their actual behaviour in predicting relationship satisfaction and commitment (see Montoya et al. 2008). This is another potential area for future research, where studies could obtain reports from both partners to address this. Finally, the current study only explored mate-retention strategies among heterosexual individuals. Given that sexual orientation influences the performance of mate-retention strategies (Brewer and Hamilton 2014), future studies should address homosexual relationship dynamics.

Despite these limitations, the current research extends previous findings on the association between mate retention, relationship satisfaction and commitment. Additionally, partners’ mate-retention strategies appear to be mutually related, such that partners respond to each other’s strategies, which also depends on relationship satisfaction. Our findings suggest that different mate-retention strategies have different levels of effectiveness, by demonstrating that whereas benefit-provisioning strategies are associated with high relationship satisfaction, which, in turn, is associated with high commitment, cost-inflicting strategies do so negatively. Although our findings suggest that cost-inflicting strategies are damaging for the relationship, individuals may still find them useful in specific situations under the threat of imminent infidelity, for example, otherwise individuals would not rely on them. Despite the existence of cost-inflicting strategies, however, benefit-provisioning strategies appear to be more effective in maintaining stable and satisfying relationships.

Data Availability

The data and materials used in the research are available upon request. The data and materials can be obtained by emailing Bruna Nascimento at nascimento.brunads@gmail.com.

References

Albert, G., & Arnocky, S. (2016). Use of mate retention strategies. In T. K. Shackelford & V. A. Weekes-Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science (pp. 1–11). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16999-6_151-1.

Atari, M., Barbaro, N., Sela, Y., Shackelford, T. K., & Chegeni, R. (2017). The big five personality dimensions and mate retention behaviors in Iran. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 286–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.08.029.

Barbaro, N., Pham, M. N., & Shackelford, T. K. (2015). Solving the problem of partner infidelity: Individual mate retention, coalitional mate retention, and in-pair copulation frequency. Personality and Individual Differences, 82, 67–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.02.033

Brewer, G., & Hamilton, V. (2014). Female mate retention, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 8(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0097245.

Buss, D. M. (1988). From vigilance to violence: Tactics of mate retention in American undergraduates. Ethology and Sociobiology, 9, 291–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/0162-3095(88)90010-6.

Buss, D. M., Shackelford, T. K., & McKibbin, W. F. (2008). The mate retention inventory-short form (MRI-SF). Personality and Individual Differences, 44(1), 322–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.08.013.

Campbell, L., & Ellis, B. J. (2005). Commitment, love, and mate retention. In D. Buss (Ed.), The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (pp. 419–442). Hoboken: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470939376.ch14.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Conlon, K. E. (2019). Mate retention strategies of dominance-oriented and prestige-oriented romantic partners. In T. K. Shackelford & V. A. Weekes-Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science (Vol. 5, pp. 1–11). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-019-00189-x.

Conroy-Beam, D., Goetz, C. D., & Buss, D. M. (2015). Why do humans form long-term mateships? An evolutionary game-theoretic model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 51, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2014.11.001.

Conroy-Beam, D., Goetz, C., & Buss, D. M. (2016). What predicts romantic relationship satisfaction and mate retention intensity? Mate preference fulfillment or mate value discrepancies? Evolution and Human Behavior, 37(6), 440–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.04.003.

Dainton, M. (2015). An interdependence approach to relationship maintenance in interracial marriage. Journal of Social Issues, 71(4), 772–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12148.

Dandurand, C., & Lafontaine, M. F. (2014). Jealousy and couple satisfaction: A romantic attachment perspective. Marriage & Family Review, 50(2), 154–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2013.879549.

Danel, D. P., Siennicka, A., Glińska, K., Fedurek, P., Nowak-Szczepańska, N., Jankowska, E. A., et al. (2017). Female perception of a partner’s mate value discrepancy and controlling behaviour in romantic relationships. Acta Ethologica, 20(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10211-016-0240-5.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149.

French, J. E., Meltzer, A. L., & Maner, J. K. (2017). Men’s perceived partner commitment and mate guarding: The moderating role of partner’s hormonal contraceptive use. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 11(2), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000087.

Funk, J. L., & Rogge, R. D. (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the couples satisfaction index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 572–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572.

Gaines Jr., S. O. (1996). Impact of interpersonal traits and gender-role compliance on interpersonal resource exchange among dating and engaged/married couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13(2), 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407596132005.

Gleason, M. E., Iida, M., Bolger, N., & Shrout, P. E. (2003). Daily supportive equity in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(8), 1036–1045. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203253473.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Joel, S., Gordon, A. M., Impett, E. A., MacDonald, G., & Keltner, D. (2013). The things you do for me: Perceptions of a romantic partner’s investments promote gratitude and commitment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(10), 1333–1345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213497801

Kardum, I., Hudek-Knezevic, J., Gračanin, A., & Mehic, N. (2017). Assortative mating for psychopathy components and its effects on the relationship quality in intimate partners. Psychological Topics, 26(1), 211–239. https://doi.org/10.31820/pt.26.1.10.

Kelley, H. H., & Thibaut, J. W. (1978). Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. New York: Wiley.

Le, B., Dove, N. L., Agnew, C. R., Korn, M. S., & Mutso, A. A. (2010). Predicting nonmarital romantic relationship dissolution: A meta-analytic synthesis. Personal Relationships, 17(3), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01285.x.

Little, A. C., Burt, D. M., & Perrett, D. I. (2006). What is good is beautiful: Face preference reflects desired personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 41(6), 1107–1118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.015.

De Miguel, A. & Buss, D. M. (2011). Mate retention tactics in Spain: personality, sex differences, and relationship status. Journal of Personality, 79(3), 563–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00698.x

Montoya, R. M., Horton, R. S., & Kirchner, J. (2008). Is actual similarity necessary for attraction? A meta-analysis of actual and perceived similarity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(6), 889–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407508096700.

Ogolsky, B. G. (2009). Deconstructing the association between relationship maintenance and commitment: Testing two competing models. Personal Relationships, 16(1), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2009.01212.x.

Orr, H. A. (2009). Fitness and its role in evolutionary genetics. Nature Reviews Genetics, 10(8), 531–539. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2603.

Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (2010). Should I stay or should I go? Predicting dating relationship stability from four aspects of commitment. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 543–550. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021008.

Rusbult, C. E. (1983). A longitudinal test of the investment model: The development (and deterioration) of satisfaction and commitment in heterosexual involvements. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 101–117. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.395.4436&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Rusbult, C. E., & Farrell, D. (1983). A longitudinal test of the investment model: The impact on job satisfaction, job commitment, and turnover of variations in rewards, costs, alternatives, and investments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(3), 429–438. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.68.3.429.

Rusbult, C. E., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (2003). Interdependence, interaction, and relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 351–375. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145059.

Rusbult, C. E., Martz, J. M., & Agnew, C. R. (1998). The investment model scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Personal Relationships, 5(4), 357–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00177.x.

Salmon, C. (2017). Long-term romantic relationships: Adaptationist approaches. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 11, 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000081.

Sela, Y., Mogilski, J. K., Shackelford, T. K., Zeigler‐Hill, V., & Fink, B. (2017). Mate value discrepancy and mate retention behaviors of self and partner. Journal of Personality, 85(5), 730–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12281

Shackelford, T. K., & Buss, D. M. (1997). Marital satisfaction in evolutionary psychological perspective. In R. J. Steinberg & M. Hojjat (Eds.), Satisfaction in close relationships (pp. 7–25). New York: Guilford Press.

Shackelford, T. K., & Buss, D. M. (2000). Marital satisfaction and spousal cost-infliction. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(5), 917–928. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00150-6.

Shackelford, T. K., Goetz, A. T., Buss, D. M., Euler, H. A., & Hoier, S. (2005). When we hurt the ones we love: Predicting violence against women from men's mate retention. Personal Relationships, 12(4), 447–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2005.00125.x

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2005). Conceptual foundations of evolutionary psychology. In D. M. Buss (Ed.), Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (pp. 5–67). John Wiley & Sons.

Valentova, J. V., Varella, M. A. C., Bártová, K., Štěrbová, Z., & Dixson, B. J. W. (2017). Mate preferences and choices for facial and body hair in heterosexual women and homosexual men: Influence of sex, population, homogamy, and imprinting-like effect. Evolution and Human Behavior, 38(2), 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.10.007.

Welling, L. L., Puts, D. A., Roberts, S. C., Little, A. C., & Burriss, R. P. (2012). Hormonal contraceptive use and mate retention behavior in women and their male partners. Hormones and Behavior, 61(1), 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.10.011.

Yong, J. C., & Li, N. P. (2018). The adaptive functions of jealousy. In The Function of Emotions (pp. 121–140). Cham: Springer.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Capes Foundation, Ministry of Education – Brazil (99999.001967/2015-00).

Funding

Capes Foundation, Ministry of Education – Brazil (99999.001967/2015-00).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

None.

Declarations

Not applicable.

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the psychology ethics committee of the University of Bath (ethical approval code: 17-218).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nascimento, B., Little, A. Relationship satisfaction mediates the association between perceived partner mate retention strategies and relationship commitment. Curr Psychol 41, 5374–5382 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01045-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01045-z