Abstract

Self-compassion offers profound benefits to well-being and healthy psychological functioning. Surprisingly however, the relationship assumed between compassion for self and others has been questioned by recent research findings and is at best inconsistently correlated. The aim of this study is to throw further light on this debate by testing whether the association between self-compassion and compassion for others is moderated by authenticity amongst 530 participants who completed the Authenticity Scale, the Self-Compassion Scale, and the Compassion Scale. The results show that authenticity has a moderation effect on the association between self-compassion and the kindness, common humanity, mindfulness, and indifference subscales of the Compassion Scale. These results offer some initial insight into understanding the association between compassion for self and others and establish a case for researching the role of authenticity more thoroughly. The findings of this investigation call for further empirical attention to socially constructive aspects of authenticity and the development of new authenticity measurements that may better assess the interaction effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In today’s world in which there are racially motivated murders, violence on the streets between people of different political views, and a culture of social media that promotes divisive messages, we need to cultivate a world in which we have more compassion for each other. It might be expected that compassion for others starts with compassion for ourselves, but is this always the case? This is an important question for social psychologists in their attempt to understand how we might develop a more compassionate world. In this study we investigate the association between self-compassion and other compassion and whether their relationship may be moderated by authenticity.

In recent years, self-compassion has been empirically investigated in a growing body of psychological studies (e.g. Anjum et al. 2020; Phillips 2019; Tandler and Petersen 2020; Temel and Atalay 2018). According to Neff (2016), self-compassion involves kindness towards oneself, with an ability to regard one’s distressing experiences as both inevitable and impermanent as well as something that connects rather than isolates us from others, and an awareness of our thoughts, feelings, and emotions. Given the inescapable nature of human suffering, it is thought that self-compassion can have a transformative positive psychological effect. Much research has now documented the nature and personal benefits of self-compassion (e.g. Gerber et al. 2015; Kavaklı et al. 2020; Neff et al. 2007; Steindl et al. 2018; Stephenson et al. 2018; Stoeber et al. 2020; Terry and Leary 2011; Tou et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2019). While many benefits have been reported for self-compassion, it has been assumed, intuitively, that such a tendency would also be related to greater compassion for others. Indeed, the word compassion comes from the Latin word compati, in which com means “together with”, and pati means “suffer with” (Burnell 2009). Research has however questioned this assumption and recent literature has offered contradictory findings about the association between self-compassion and compassion for others.

Some previous evidence suggests a positive association between self-compassion and compassion for others. In the first such study, Neff and Pommier (2013) investigated the relationship between self-compassion and other-focused concern among three diverse groups: college students, community adults, and practicing Buddhist meditators. It was found that the strength of the relationship between self-compassion and compassion for others changed according to participant groups. The correlation between compassion for self and others was significantly stronger for the meditators than for the community adults or the college students. Why should the strength of the relationship between self-compassion and other-compassion be different according to the sample? Neff and Pommier (2013) speculate that developmental processes may play a role in the extent to which people are concerned with the welfare of others, suggesting that these results could reflect a process of emotional maturity. Another study by Fulton (2018) collected data from adults who were students on a Masters-level course in counselling also finding a moderately strong correlation between compassion for self and compassion for others.

On the other hand, three studies with adult general population samples have reported no statistically significant association between self-compassion and compassion toward others. Gerber et al. (2015) investigated the relationship between self-compassion and healthy concern for others; they did not find any relationship. Likewise, Lopez et al. (2018) showed that compassion for others and self-compassion were only weakly and not statistically significantly correlated. Similar results were again obtained by Stoeber et al. (2020) who also reported that the correlation between self-compassion and compassion for others was weak and not statistically significant. All three studies had sufficiently large sample sizes to detect such statistical associations. As such, these contradictory findings across several studies on the association between self-compassion and compassion for others are perplexing and the topic deserves further scrutiny.

One possible explanation for the difference in results across these studies may be the different samples. The two studies that have shown a positive association, Neff and Pommier (2013) and Fulton (2018), consisted of a sample of meditators and students studying for a counseling qualification, respectively. One would expect that counseling students, like meditators, are engaged in personal development work that would lead to greater emotional maturity. As such, it may be that Neff and Pommier’s (2013) suggestion that developmental processes reflecting emotional maturity are important in explaining the nature of the relationship between self-compassion and compassion for others is correct.

Building on Neff and Pommier’s (2013) suggestion, we hypothesize that authenticity may be a dispositional factor that moderates the relationship between compassion for self and others. Authenticity is understood as a high level of psychological maturity representing the culmination of a process of personal development and emotional competence characterized by deep self-awareness, agency in the world and the ability to be open and honest in relations with both oneself and others (Joseph 2016). It would be expected that higher levels of authenticity would be present in those engaging in counseling training as in Fulton’s (2018) study or Neff and Pommier’s (2013) practising Buddhist meditators.

Authenticity is a topic that has also attracted much new empirical interest in recent years (e.g. Borawski 2019; Koydemir et al. 2018; Ryan and Ryan 2019) and some research has demonstrated the relationship between authenticity and compassion for self and others. For example, Zhang et al. (2019) conducted five studies within different cultures showing that self-compassion is positively associated with authenticity. It was proposed in this study that when people feel self-compassionate, they are more inclined to feel authentic. A previous study by Tou et al. (2015) also shows evidence that authenticity and compassion for others are associated, suggesting that authentic individuals may care about the needs of others in cases of relational conflict. Thus, while we know that authenticity may have an association with compassion-related variables, the hypothesis that it moderates the association between self-compassion and other compassion remains to be tested. Therefore, the present research explores, for the first time, the speculative role that authenticity may play in moderating the association between self-compassion and other compassion.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The sample consisted of 530 Turkish-speaking participants. It comprised 152 men (28.7%), 374 women (70.6%), and 4 identified as ‘others’ (0.8%), i.e., who prefer to identify themselves neither as female or as male. Age ranged from 18 to 76 years (M = 34, SD = 11.6). Table 1 provides complete demographic characteristics of the sample.

All participants provided informed consent in accordance with the University Ethics Committee, which provided permission for the study to be conducted. The involvement was wholly voluntary and anonymous. Data were collected using an online questionnaire via Bristol Online Survey (now ‘Online Surveys’), reputed for high data protection standards. Using the internet for data collection is regarded as a validated and ethical method of acquiring anonymous survey data when necessary safeguards are adhered to (Nayak and Narayan 2019). With the aim of eliminating missing data problems that result in miscalculations, this study enabled a ‘forced responding’ option whereby participants cannot access further questions until answering the current one. Therefore, the completion rate was 100%.

This study used a snowball approach to sampling to recruit participants, comprising friends and acquaintances. With the aim of publicizing the study to a wider range of respondents, participants were asked to share the website link for the online survey with their family and friends. As a snowball sample, however, we cannot be sure of how many people came into contact with the link and had the opportunity to complete the survey but declined. After completion of a series of demographic questions, participants completed a battery of three self-report measures, described forthwith.

Measures

Authenticity Scale (AS; Wood et al. 2008)

This 12-item self-report measure has three 4-item subscales to evaluate: Authentic living (e.g., “I am true to myself in most situations”), self-alienation (e.g., “I feel as if I don’t know myself very well”), and accepting external influence (e.g., “I always feel I need to do what others expect me to do”). All items are answered on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (= does not describe me at all) to 7 (= describes me very well). Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients were found to range from .69 to .78 (Wood et al. 2008) and for the Turkish version that we used the values were .62 for authentic living, .79 for self-alienation, and .67 for accepting external influence (İlhan and Özdemir 2013). The total score for the AS involves reverse scoring eight negatively worded items and then calculating the mean for 12 items such that higher scores indicate greater authenticity.

Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff 2003)

The SCS is a 26-item self-report measure of compassionate behavior towards oneself. There are six subscales: (1) Self-kindness (e.g., “I try to be understanding and patient towards those aspects of my personality I don’t like.”), (2) self-judgment (e.g., “I can be a bit cold-hearted towards myself when I’m experiencing suffering.”), (3) common humanity (e.g., “When I feel inadequate in some way, I try to remind myself that feelings of inadequacy are shared by most people.”), (4) isolation (e.g., “When I fail at something that’s important to me, I tend to feel alone in my failure.”), (5) mindfulness (e.g., “When I’m feeling down I try to approach my feelings with curiosity and openness.”) and (6) over-identification (e.g., “When something painful happens I tend to blow the incident out of proportion.”). The SCS can also be scored to yield a total score for the 26 items, each of which is rated by respondents on a scale from 1 (= almost never) to 5 (= almost always). Each of the subscales was found to have adequate internal consistency reliability; Cronbach’s alpha = .78 for self-kindness, .77 for self-judgement, .80 for common humanity, .79 for isolation, .75 for mindfulness, and .81 for over-identification. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the total scale was .89 (Deniz et al. 2008). The total score for the SCS involves calculating the mean for all 26 items such that higher scores indicate greater self-compassion.

Compassion Scale (CS; Pommier 2011)

The CS consists of six 4-item subscales of kindness (e.g., “If I see someone going through a difficult time, I try to be caring toward that person.”), indifference (e.g., “Sometimes when people talk about their problems, I feel like I don’t care.”), common humanity (e.g., “It’s important to recognize that all people have weaknesses and no one’s perfect.”), separation (e.g., “I can’t really connect with other people when they’re suffering.”), mindfulness (e.g., “When people tell me about their problems, I try to keep a balanced perspective on the situation”), and disengagement (e.g., “I try to avoid people who are experiencing a lot of pain.”). All items are rated on a 5-point frequency scale ranging from 1 (= almost never) to 5 (= almost always). This scale has satisfactory internal consistency for each item; Cronbach’s alpha = .77 for kindness, .68 for indifference, .70 for common humanity, .64 for separation, .67 for mindfulness, and .57 for disengagement. For the Turkish version: Cronbach’s alpha = .66 for kindness, .60 for indifference, .60 for common humanity, .68 for separation, .68 for mindfulness, and .71 for disengagement (Akdeniz and Akdeniz and Deniz 2016). The total score for the CS involves calculating the mean for all 24 items such that higher scores indicate greater compassion for others.

Each of the three scales employed are widely used in the empirical literature on these topics, have been shown to be psychometrically sound and theoretically valid, and as noted previously have been adapted and validated for use by Turkish Language speakers.

Statistical Analysis

This cross-sectional survey-based study examined the moderating effect of authenticity on the relationship between self-compassion and compassion for others. Data analysis was carried out via SPSS, 24.0. Several t-test and ANOVAs were run to investigate whether authenticity, self-compassion and compassion for others scores differ based on demographic variables (i.e. age, gender, marital status, educational status, occupation). To do so, the variable of age was dichotomized into young (18–24) and adult (25+) according to age categorization of World Health Organization (2020); the variable of marital status was classified into “married/in a relationship” and “single”; the variable of educational status was categorized into “low”, “middle”, “high”; the variable of occupation was divided into “employed” and “unemployed”.

A-priori sample size calculator for hierarchical multiple regression (Soper 2020) was used. In this regard anticipated effect size was entered as 0.20, considered to be small using Cohen's (1988) criteria, desired statistical power level was entered as 0.99. The proposed sample size was 124. Thus, our sample size of 530 was more than adequate for the main objective of this study. Preliminary analyses demonstrated the association to be linear with both variables normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk’s test (p > .05), and there were no outliers. Based on our research question, hierarchical multiple regression was used to test the hypothesized moderating effect of authenticity upon the association between Self-Compassion Scale and Compassion Scale. The figures of moderation analysis were generated using SPSS macro PROCESS (Hayes 2013).

Results

First the means, standard deviations, and internal consistency reliability across all scales and the correlations between scores on the AS, SCS, and CS for others are presented, followed by their differences between demographic groups, and finally, the regression analyses testing the moderating effect of authenticity upon the six subscales of the CS.

The overview of the means, standard deviations, and internal consistency reliability for all scales are provided (see Table 2). As the results indicate, internal consistency reliabilities were high. A Pearson’s product-moment correlation was run to assess the association between authenticity, self-compassion and compassion for others. All three subscales of the AS were correlated with all six subscales of the SCS in the expected directions. With only one exception, namely the non-significant correlation between ‘kindness’ and ‘accepting external influence’, all three subscales of the AS correlated with all six subscales of CS in expected directions providing support that greater authenticity is associated with greater kindness, less indifference, greater common humanity, less separation, greater mindfulness and less disengagement. As such, for the subsequent analyses we thought it appropriate to use only the total scores. There was a statistically significant strong association between the AS and the SCS, r (530) = .54, p < .0005. Also, the AS was found to have a significant and moderate association with the CS, r (530) = .31, p < .0005. The SCS had a significant, yet weak positive association with the CS, r (530) = .24, p < .0005.

Table 3 shows the mean scores for the different demographic groups. Results revealed that adults had higher scores than young people on the AS (t (528) = −2.864, p = .004) and the SCS (t (528) = −3.116, p = .002). It was also found that female participants showed higher scores on the CS (t (524) = −6.243 p = .000), but lower scores on the SCS (t (407) = 4.788, p = .029) compared to male participants. In terms of marital status, participants who are married or in a relationship had higher scores on the AS (t (528) =3.768, p = .000) and the CS (t (528) = 3.081, p = .002) compared to single participants (see Table 3).

Testing of Moderation Effect

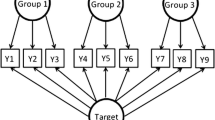

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to test the moderating effect of authenticity. Self-compassion was entered at Step 1, explaining 5.7% of the variance in compassion for others. As shown in Table 4, the coefficient of determination ΔR2 is .05 and The Beta value (β = .24) of SCS was found to be positive and statistically significant on authenticity. Thus, self-compassionate people are more inclined to act compassionately to others. After the entry of Authenticity Scale at the second step, the total variance explained by the model as a whole was 10.6%, F(2, 527) = 31.33, p < .001. The Authenticity Scale explained an additional 4.90% of the variance in compassion for others controlling for self-compassion, F(1, 527) = 28.80, p < .001. The coefficient of determination ΔR2 increased from .05 to .10, indicating that authenticity has explanatory power on the relationship between self-compassion and compassion for others. In the third step, the interaction term between self-compassion and authenticity was entered. The first requirement which must be fulfilled in the case of moderation is that the interaction term must show statistical significance (Morana 2003). The Beta value (β = .62, p = .08) of the interaction term between self-compassion and authenticity showed a trend towards statistical significance; such that at higher levels of self-compassion, the level of authenticity seems to make a difference. Even though the statistical significance of interaction term does not meet the arbitrary cut-off level of 0.05 (Grunkemeier et al. 2009), it is not ‘nil’ either because of the fact that the null hypothesis can be true by 8% chance (Pitak-Arnnop et al. 2010). Figure 1 shows the plot of the trend towards interaction, created by performing PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013). The final model explained 11% of the total variance, F(3, 526) = 21.93, p < .001.

While these results did not provide support for our hypothesis of an interaction between scores on the Authenticity Scale and the Self-Compassion Scale, because of the strong trend towards statistical association it seemed likely to us that if we were to repeat the analysis for each of the CS subscales we would likely observe statistically significant differences for some subscales. As such, we therefore proceeded to also test for interaction between the Authenticity Scale and the Self-Compassion Scale for each of the six subscales of the Compassion Scale (see Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10). In each analysis, Self-Compassion was entered at Step 1, Authenticity at step two, and in the third step, the interaction term between self-compassion and authenticity.

For each of the kindness, common humanity, mindfulness, and indifference subscales, the interaction term entered in the third step was found to be statistically significant. It was found that at higher levels of self-compassion, that the level of authenticity made the difference, with high authentic individuals showing greater kindness, mindfulness and less indifference (see Figs. 2, 3 and 4). While these results were consistent with our hypotheses, two observations seemed noteworthy because they were contrary to our expectations. First, was the slight trend in Fig. 2 towards less kindness in those high in self-compassion but low in authenticity. Second, for common humanity, there was also an interaction found but it was at lower levels of self-compassion, that the level of authenticity made the difference (see Fig. 5). No statistically significant interactions were found for the subscales of separation or disengagement (See Figs. 6 and 7).

Discussion

It might be expected that those with more self-compassion are more compassionate for others. However, previous research has not always found this to be the case. In order to address this intriguing issue, we hypothesized the possibility of relationship between self-compassion and compassion for others that is moderated by authenticity. It was revealed that authenticity was a significant moderator of the relationship between self-compassion and kindness, common humanity, mindfulness, and indifference, respectively.

While many researchers have found personal benefits for self-compassion, it has also been criticized as self-indulgence, self-absorption or self-orientation (Bayır and Lomas 2016; Neff 2003). Certainly, the lack of evidence for its association with compassion for others would seem to lend some support to these criticisms, as would our observation that without authenticity it may even be related to less kindness. However, in the context of authenticity, the cultivation of self-compassion would seem to have benefits for how people approach others more compassionately. While it must also be noted that the interaction effects are not strong, the finding that authenticity moderates the association between self-compassion and other-compassion related variables is important in offering an explanation for the previously discrepant findings and opens up new avenues for research.

Further studies regarding the socially constructive role of authenticity would be worthwhile. Previous empirical studies have also reported on the intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of authenticity (e.g. Didonato and Krueger 2010; Lynch and Sheldon 2017). Humanistic psychologists such as Rogers (1959, 1961) have long understood authenticity as a within person factor that reveals the socially constructive aspects of human nature. That is, the more authentic a person is, the more a person will exhibit what Rogers believed were the essential positive psychological characteristics of human beings, as opposed to the distorted and destructive tendencies often exhibited by people but understood to arise from inauthenticity (Joseph 2015). However, authenticity is difficult to assess using self-report methods, with questions about their validity. Completion of the Authenticity Scale requires a degree of self-awareness and may be influenced by social desirability to answer in particular ways. Hence, other tools may yet need to be developed that can more effectively test the interaction hypothesis.

Also, the current study found that females are more compassionate to others than men. In accordance with our results, previous studies have demonstrated the same gender difference with respect to compassion for others (Lopez et al. 2018; Neff and Pommier 2013; Stellar et al. 2012). On the other hand, self-compassion was found lower for female participants and this results corroborates the findings of Yarnell et al. (2015) whose meta-analysis reported lower self-compassion scores for women. Consistent with the literature (Lopez et al. 2018; Stellar et al. 2012), this research found that low-educated participants have higher scores of compassion for others. However, this study showed that the self-compassion levels of low-educated individuals is higher than middle-educated and high-educated participants. This outcome is contrary to that of Lopez et al. (2018) who found that self-compassion is lower in lower-educated individuals.

This research is the first study to empirically investigate the relationship between authenticity, self-compassion and compassion for others. However, there are three limitations to disclaim. First, the study was limited to Turkish-speaking participants. While it seems unlikely that our results are culture specific, it would be informative to replicate elsewhere. Second, the data were collected by self-report questionnaires, which as aforementioned may be affected by socially desirable responding. Apart from Neff and Pommier (2013) who controlled for social desirability, none of the subsequent studies have done this. Future studies should replicate the current findings with this factor controlled for. It would also be beneficial to assess compassion towards others using more objective behavioral indices where possible. Third, there is a need for longitudinal data to help establish the causal nature of the relationships between these variables beyond what is possible with cross-sectional data. We are assuming that there is a relationship in which self-compassion leads to other compassion but it may be that it is through learning to be more compassionate towards others that one learns to be more compassionate to oneself, or there is no causal relationship between self-compassion and other compassion and both are a function of the development of authenticity. In conclusion, our results seem to provide an answer to what has become a perplexing question in the literature about compassion concerning the inconsistency between studies testing for association between self-compassion and compassion for others.

References

Akdeniz, S., & Deniz, E. (2016). Merhamet Ölçeği'nin Türkçe'ye uyarlanması: Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. The Journal of Happiness & Well-Being, 4(1), 50–61.

Anjum, M. A., Liang, D., Durrani, D. K., Durrani, D. K., & Parvez, A. (2020). Workplace mistreatment and emotional exhaustion: The interaction effects of self-compassion. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00673-9.

Bayır, A., & Lomas, T. (2016). Difficulties generating self-compassion: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. The Journal of Happiness & Well-Being, 4(1), 15–33.

Borawski, D. (2019). Authenticity and rumination mediate the relationship between loneliness and well-being. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00412-9.

Burnell, L. (2009). Compassionate care: A concept analysis. Home Health Care Management & Practice, 21, 319–324.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Deniz, E., Kesici, Ş., & Sümer, S. (2008). The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the self-compassion scale. Social Behavior and Personality, 36(9), 1151–1160.

Didonato, T., & Krueger, J. (2010). Interpersonal affirmation and self-authenticity: A test of Rogers's self-growth hypothesis. Self and Identity, 9(3), 322–336.

Fulton, C. L. (2018). Self-compassion as a mediator of mindfulness and compassion for others. Counseling and Values, 63(1), 45–56.

Gerber, Z., Tolmacz, R., & Doron, Y. (2015). Self-compassion and forms of concern for others. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 394–400.

Grunkemeier, G. L., Wu, Y., & Furnary, A. P. (2009). What is the value of a p value? The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 87(5), 1337–1343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.03.027.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

İlhan, T., & Özdemir, Y. (2013). Adaptation of authenticity scale to Turkish: A validity and reliability study. Türk Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Dergisi, 5(40), 142–153.

Joseph, S. (2015). Positive therapy. Building bridges between positive psychology and person-centred psychotherapy. London: Routledge.

Joseph, S. (2016). Authentic. How to be yourself and why it matters. London: Little-Brown.

Kavaklı, M., Ak, M., Uğuz, F., &Türkmen, O.O. (2020). The mediating role of self- compassion in the relationship between perceived Covid-19 threat and death anxiety. Turkish Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 23. https://doi.org/10.5505/kpd.2020.59862.

Koydemir, S., Şimşek, Ö. F., Kuzgun, T. B., & Schütz, A. (2018). Feeling special, feeling happy: Authenticity mediates the relationship between sense of uniqueness and happiness. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9865-z.

Lopez, A., Sanderman, R. A., & Schroevers, M. (2018). Compassion for others and self-compassion: Levels, correlates, and relationship with psychological well-being. Mindfulness, 9(1), 325–331.

Lynch, M., & Sheldon, K. (2017). Conditional regard, self-concept, and relational authenticity. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 1–19.

Morana, C. L. (2003). Appraisal and coping: Moderators or mediators of stress in Alzheimer’s disease caregivers? Social Work Research, 27(2), 116–128.

Nayak, M., & Narayan, K. (2019). Strengths and weakness of online surveys. Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 24(5), 31–38.

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2, 223–250.

Neff, K. D. (2016). The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness, 7(1), 264–274.

Neff, K., & Pommier, E. (2013). The relationship between self-compassion and other-focused concern among college undergraduates, community adults, and practicing mediators. Self and Identity, 12(2), 160–176.

Neff, K. D., Rude, S. S., & Kirkpatrick, K. (2007). An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 908–916.

Phillips, W. J. (2019). Self-compassion mindsets: The components of the self-compassion scale operate as a balanced system within individuals. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00452-1.

Pitak-Arnnop, P., Dhanuthai, K., Hemprich, A., & Pausch, N. C. (2010). Misleading p-value: Do you recognise it? European journal of dentistry, 4(3), 356–358.

Pommier, E. A. (2011). The compassion scale. Dissertation abstracts international section A. Humanities and Social Sciences, 72, 1174.

Rogers, C. R. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships as developed in the client-centred framework. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of a science, Formulations of the person and the social context (Vol. 3, pp. 184–256). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. London: Constable.

Ryan, W. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2019). Toward a social psychology of authenticity: Exploring within-person variation in autonomy, congruence, and genuineness using self-determination theory. Review of General Psychology, 23(1), 99–112.

Soper, D. S. (2020). A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Hierarchical Multiple Regression [Software]. Available from http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc

Steindl, S. R., Matos, M., & Creed, A. K. (2018). Early shame and safeness memories, and later depressive symptoms and safe affect: The mediating role of self-compassion. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9990-8.

Stellar, J. E., Manzo, V. M., Kraus, M. W., & Keltner, D. (2012). Class and compassion: Socioeconomic factors predict responses to suffering. Emotion, 12, 449–459.

Stephenson, E., Watson, P. J., Chen, Z. J., & Morris, R. (2018). Self-compassion, self-esteem, and irrational beliefs. Current Psychology, 37, 809–815.

Stoeber, J., Lalova, A., & Lumley, E. (2020). Perfectionism, (self-)compassion and subjective well-being: A mediation model. Personality and Individual Differences, 154, 109708.

Tandler, N., & Petersen, L. (2020). Are self-compassionate partners less jealous? Exploring the mediation effects of anger rumination and willingness to forgive on the association between self-compassion and romantic jealousy. Current Psychology, 39, 750–760.

Temel, M., & Atalay, A. A. (2018). The relationship between perceived maternal parenting and psychological distress: Mediator role of self-compassion. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9904-9.

Terry, M., & Leary, M. (2011). Self-compassion, self-regulation, and health. Self and Identity, 10(3), 352–362.

Tou, R., Baker, Z. G., Hadden, B. W., & Lin, Y. (2015). The real me: Authenticity, interpersonal goals, and conflict tactics. Personality and Individual Differences, 86, 189–194.

Wang, Y., Yang, J., Wang, J., Yin, L., & Lei, L. (2020). Body talk on social networking sites and body dissatisfaction among young women: A moderated mediation model of peer appearance pressure and self-compassion. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00704-5.

Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M., & Joseph, S. (2008). The authentic personality: A theoretical and empirical conceptualization and the development of the authentic scale. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 55(3), 385–399.

World Health Organization. (2020). Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/adolescent-health.

Yarnell, L. M., Stafford, R. E., Neff, K. D., Reilly, E. D., Knox, M. C., & Mullarkey, M. (2015). Meta-analysis of gender differences in self- compassion. Self and Identity, 14, 499–520.

Zhang, J., Chen, S., Tomova, T., Bilgin, B., Chai, W., Ramis, T., Shaban-Azad, H., Razavi, P., Nutankumar, T., & Manukyan, A. (2019). A compassionate self is a true self? Self-Compassion promotes Subjective Authenticity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(9), 1323–1337.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bayır-Toper, A., Sellman, E. & Joseph, S. Being yourself for the ‘greater good’: An empirical investigation of the moderation effect of authenticity between self-compassion and compassion for others. Curr Psychol 41, 4871–4884 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00989-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00989-6