Abstract

The temperamental trait of perseverance is suspected to be a cause for ruminations present in many different affective disorders, especially depression. We predicted that higher-order cognition, including self-complexity, would mediate the role of perseverance. In the current study, we used the Formal Characteristics of Behavior–Temperament Inventory (FCB–TI), the Rumination–Reflection Questionnaire and Evans’ Self-Complexity Inventory (SCI) to measure the factors included in the tested model. We found that a strong positive relation between perseverance and ruminative thoughts is partially mediated by self-complexity. This result shows how important it is to include the complex cognitive processes in personality formation to understand the role of temperament in the development of ruminative thoughts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research in the psychology of personality and temperament offers an ever-expanding knowledge of relations between basic, measurable traits of mind and behavior. Although those links deepen the understanding of the human mind, a rigid approach towards temperament comes with the risk of reducing psychology to determinism. The current paper aims to integrate various fields of knowledge of the human mind. The main focus of current research is to explore how basic temperamental traits affect cognition and how self-representation might alter this relationship.

In past research, a temperamental trait of perseverance (Strelau and Zawadzki 1995) has been shown to affect various spheres of behavior and cognition (Manfredi et al. 2011). One vital relationship has been discovered – perseverance has been shown to predict rumination, a thought pattern deemed inadaptive and itself correlated with affective disorders. Although it is pointed out that the onset of affective disorders relies on both environmental stressors and internal factors, researchers also link it with the varying vulnerability to stress encountered by the person (Kendler et al. 2004). Personality – or, in the narrower sense, temperamental traits – has been shown to affect the occurrence of specific cognitive strategies, which tend to shape the onset and course of depressive symptoms (Carter et al. 2009; Smith et al. 2006). These thought patterns, called ruminations, force the afflicted person to relive and ponder past aversive experiences. It has been pointed out that rumination correlates with some of the person’s temperamental traits (Manfredi et al. 2011). This is especially valid for the trait of perseverance, proposed in the Regulatory Theory of Temperament (Strelau and Zawadzki 1995). This trait is defined as a tendency to continue the activity after stimulation ceases. It can be seen that, conceptually, ruminations correspond to perseverance on the level of cognition. This theoretical affinity seems to be validated by empirical data (Hintsa et al. 2016). On the other hand, research seems to point to a relationship between rumination and depressive symptoms, which sometimes is qualified as causal (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2007). Some papers (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema 2000) provide evidence of the predictive value of the presence of rumination on depressive symptoms. However, up to this point, this relationship was seen as rather direct and rigid.

Temperament, seen as the rudimentary architecture of human cognition and emotion, inevitably has a strong effect on behavior and, in certain configurations, on psychopathology (Mezulis et al. 2011). Given that temperament, in large part, is genetically preconditioned and also considering its temporal stability (McCrae and Costa Jr 1994), one runs the risk of assuming genetic determinism in psychology. However, the existence of mediating variables located within spheres of human functioning other than temperament (Brausch and Decker 2014), more prone to change in the course of therapy or individual activity, seems to undermine that notion. One of the concepts of considerable interest, as far as self-protective factors are concerned, is self-complexity. As proposed by Linville (1985), self-complexity is the structure of self-representation that might have serious implications for various spheres of psychological functioning, including affect and self-appraisal. It has been observed that lower levels of complexity of self-representation predict greater affective swing in cases of stress. From that fact, Linville has predicted that high self-complexity may play the role of a buffer against depressive moods. With further evidence provided by Evans (1994), it can be seen that self-complexity indeed plays a regulative role, protecting against psychopathological symptoms. What is more, Evans (1994) designed a novel measure, the Self-Complexity Inventory (SCI), that enables researchers to express this fairly complex property as a quantitative dimension. Evans (1994) tested the correlation between self-complexity in adolescents and the presence of psychopathological symptoms and hazardous behaviors. In that study, the SCI proved to be a reliable method for measuring self-complexity, having the appropriate psychometric properties. For the purposes of the current study, the SCI has been translated into Polish and preliminarily validated (cf., Method section), enabling the measurement of self-complexity reliably and in relation to the chosen sample.

The theory of self-complexity suggests a sound link between variables studied in current research. Firstly, we looked at how temperament might affect self-complexity. Perseverance, as described by the regulatory theory of temperament (Strelau and Zawadzki 1995), promotes repetitive patterns of behavior, which means that a person with a high perseverance score spends time on the same activities rather than exploring new possibilities. It also suggests that such a person stays in the same emotional state for longer, unwittingly sustaining the same thoughts and activities. This fact leads to a prediction that high perseverance hinders the development of new forms of self-development, interests and life roles. Therefore, as self-complexity theory would describe, perseverance limits the possibilities of expansion of aspects of the self, which would lower self-complexity. What is also important to note is that perseverance promotes sustaining the same response styles when encountering various stimuli. This suggests that individuals high on the perseverance score will express similar emotional reactions and attitudes in various life roles, which is a meaningful link to the second defining factor of self-complexity – overlap between aspects of the self (Linville 1985).

The predicted relationship between self-complexity and rumination also seems to find explanations in theories of both of those phenomena. Linville (1985) stated that high self-complexity might act as a buffer from a depressive mood by providing a person with additional areas (self-aspects) in which they can express more varying emotions and employ different thought patterns, thus compensating for a change of appraisal in a given area of functioning. Rumination is basically one possible thought pattern from an array of cognitive mechanisms that is activated especially when a person is confronted with stress or loss. Existing theories concerning brooding rumination (e.g., Wells and Papageorgiou 2004) underline its circular, recurring pattern. Querstret and Cropley (2013) suggest several interventions aimed at the reduction of rumination. Those interventions verified as effective assume an approach of disengagement from the emotional response to ruminative thoughts or the promotion of different response styles. It has been shown also that positive, engrossing distractions play a role in the reduction of recurrence of ruminative thoughts (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 2008). These proposals lead to the link between self-complexity and rumination. As already stated, high self-complexity manifests itself in a large number of self-aspects that differ in terms of appraisal, ascribed emotional load and also the areas of cognition in which they are processed. It is highly probable that additional, varying self-aspects provide individuals with emotions, cognitive mechanisms and content, drawing them away from inadaptive ruminative thoughts. Their role could be best described as endogenous positive distractions. Because of the reduction of time spent on recurring rumination and its emotional impact, self-complexity is believed to be negatively correlated with rumination.

The current investigation is aimed at designing and testing a potential model of mediation. As already shown, the variables form a web of correlations and it is therefore a well-founded prediction that they might be best described by a model of mediation. Assuming that temperament is a rudimentary property of the nervous system and psychological functioning, we sought to verify whether its effects could be mediated by higher-level properties such as self-complexity. The effect of a perseverance temperament on ruminative thought, as shown in existing evidence (Mezulis et al. 2011), can be regarded as substantial. Rumination has been shown to coexist with, and possibly even predict, depression. The question that this study aims to answer is whether self-complexity might negatively mediate the effect of temperament on ruminative thought. This could potentially draw science closer to the conclusion that, in fact, it is a protective factor against depression. Such a finding, in turn, could deepen our understanding of the mechanism of the disorder itself, providing for better prevention and treatment. Therefore, the primary goal of our research was to test the hypothesis that self-complexity acts as a mediator in the relationship between perseverance and rumination.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Our research was conducted with a convenience sample of 103 undergraduate students at the University of Warsaw. Participants were aged 19–24 years (M = 21.03; SD = 1.88). The sample must be deemed unrepresentative of the general population, since all participants were derived from one university department (American Studies Center) and were attending the same course. This resulted in a low variance of age. Five participants were excluded due to extensive missing data, leaving 97 for analysis, of which 64 were female. Participants who studied psychology before or in parallel were excluded from the sample.

Measures

The Formal Characteristics of Behavior–Temperament Inventory

The Formal Characteristics of Behavior–Temperament Inventory (FCB–TI: Strelau and Zawadzki 1995), in its thoroughly revised form from 2015, is a standardized measure used to evaluate seven traits of nervous system function. The questionnaire consists of 100 items, with responses on a Likert-type scale from 1 (“fully disagree”) to 4 (“fully agree”). Items reflect behaviors as determined by the seven traits. Students are asked how accurately the statements reflect their behavior in the recent past. The FCB–TI has been used primarily to assess a single trait: perseverance. A sample item for that scale is: “I quickly forget about failures I have endured”. The measure’s psychometric qualities have been studied thoroughly in several publications (e.g., Strelau and Zawadzki 1995). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the perseverance scale reported by the authors of the questionnaire is 0.75, which points towards good reliability of the scale. The current study recorded α = 0.80.

The Rumination–Reflection Questionnaire

The level of one’s ruminative thought and reflection is measured by the Rumination–Reflection Questionnaire (Trapnell and Campbell 1999); the Polish adaptation was developed by Słowińska et al. (2014). The questionnaire is comprised of two scales, each with 12 test items, with responses on a scale from 1 (“fully disagree”) to 5 (“fully agree”). Questions regard matters of focusing attention on the self, automatic thought and its influence on emotions. An example of such an item is: “I spend a great deal of time thinking back over my embarrassing or disappointing moments”. The Polish adaptation is characterized by satisfactory psychometric indices, with Cronbach’s alpha at the level of 0.96 and a temporal stability (test–retest) of 0.76.

The Self-Complexity Inventory

Self-complexity is a dimension that describes a person’s cognitive architecture, operationalized as the number of roles in which the subject functions and the level of independence between those roles (Linville 1985). The Self-Complexity Inventory (SCI) was first published by Evans (1994) in a study concerning the impact of self-complexity on several areas of functioning in adolescents, including course of development, self-esteem and occurrence of psychopathological symptoms. The scale originally consisted of eight items describing several aversive situations, followed by a request to assess one’s self-perception in 10 domains of everyday functioning on a scale of 1 (“much worse than before”) to 3 (“no different from before”). The outcomes from each item are summed up, giving the total result along an interval from 80 to 240 (with higher outcomes pointing towards higher independence of the domains of the self, hence greater self-complexity). The adaptation devised for the current study follows the same basic principles, but having more test positions (12) and reflecting domains more important to marginally older college students (young adults) rather than adolescents (as was in the original study). Thus, adaptation of the scale was performed on both linguistic and cultural levels. The new, Polish version of the SCI likewise exhibits good psychometric indices, having an internal consistency of Cronbach’s α = 0.96. Such an outcome hints at satisfying the inventory’s reliability. The distribution of the examined variable did not deviate significantly from a normal distribution, with Kolmogorov-Smirnoff at α = 0.06. The outcomes could reach the interval between 108 and 324; the average outcome was M = 242.49 (SD = 45.63). For the current research, exploratory factor analysis pointed to a single factor. Factor 1 was comprised of 12 items that explained 68% of the variance, with factor loadings from 0.749 to 0.853. This proposed single-factor model has been tested with confirmatory factor analysis. The results of the analysis are reported in Table 1 and the model shows an acceptable to good model fit. The full questionnaire can be found in Appendix 1.

Procedure

Participants completed the battery of questionnaires during the break in their lectures, in groups of 20–30 at a time. After brief instructions and information concerning the objectives of the research, tests were handed out and collected after the students had completed all items. There was no time limit; however, participants were told that completion should take approximately 20–25 min, based on the average time in a pretest sample (N = 5). Students completed the questionnaires in the following order: the FCB–TI, the Reflection–Rumination Questionnaire and then the SCI.

Statistical Approach

The integrated model of mediation has been presented and tested using AMOS. The model has been analyzed using SEM method, meaning that all the items from the scales have been used to generate estimates and model fit indices. The authors performed bootstrapping analysis, which is a proven method for testing structural models and provides a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

From the viewpoint of our hypotheses, the most relevant findings were correlations between perseverance and ruminative thought and between the self-complexity score and rumination. Perseverance was found to correlate strongly with rumination (r = 0.69; p < 0.01). As a theory of temperament would suggest, perseverance is thought of as a more rudimentary characteristic of mental functioning than rumination, which gives grounds to assume a causal relationship. In order to test this prediction, we performed linear regression analysis and the results showed that perseverance predicted rumination (R2 = 0.478) significantly better than the mean distribution of rumination.

Further steps of analysis were aimed at verifying the hypothesis that the model of mediation of self-complexity predicts rumination significantly better than simple regression between perseverance and rumination. Firstly, it was found that the self-complexity score correlated moderately with both perseverance (r = 0.38; p < 0.01) and ruminative thought (r = 0.59; p < 0.001). These data give support for testing an integrated model of mediation.

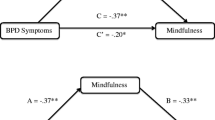

Our predictions implied that the effect of perseverance on rumination would be mediated by self-complexity. The simple mediation model has been tested using structural equation modeling. The SEM analysis in AMOS provided meaningful relationships and fitted the observed data: χ2 (659) = 855.60; p < 0.01; RMSEA = 0.056; CFI = 0.92; n = 97. Chi-square value was 855.60; df = 659; p < 0.01 for this model. Chi-square indicates if there is any difference between the sample and the fitted covariance matrices. RMSEA value was 0.056 and according to the criteria, RMSEA values of 0.05 or are deemed as an indicator of a good model fit. However, some researchers suggest that values greater than 0.05 but below 0.08 are also acceptable, especially in low sample sizes. CFI value greater or equal to 0.90 indicates an acceptable fit to the data; the resulting model obtained a CFI value of 0.92. Bootstrapping analyses with 5000 samples (Preacher and Hayes 2004; Preacher et al. 2007) revealed a significant indirect effect of perseverance on rumination via self-complexity (path a × b) of R2 = 0.110 at p < 0.05 (95% CI = 0.018–0.221). Additional path coefficients are reported in Table 2. Figure 1 displays the integrated model of mediation with the path coefficients indicated.

Discussion

The data gathered from this correlational study allow us to positively verify the initial predictions. Firstly, a strong negative correlation between self-complexity and ruminative thought has been shown. Subjects with higher self-complexity showed a lower inclination to use this maladaptive coping strategy. Secondly, the model of mediation designed for this research proved to be a satisfactory fit to the gathered data. Hence, the proposed model enables explanation of a complex variable such as rumination, understood as a circular self-attentive thought pattern guided by the perception of threat, injustice and harm to the self (Trapnell and Campbell 1999). Furthermore, it enables more accurate description and predictions of a characteristic that is seen as vital to some of the nosological entities, based on these new determinants.

These conclusions meet the predictions of past researchers and theorists and provide further explanation of the phenomenon. Linville (1985) suggested that low self-complexity might lead to a more extreme affective response to stressful events. Further research (Linville 1987) led to the conclusion that self-complexity may serve as a buffer against stress-induced mental illnesses, including depression. The current exploration positively verifies those proposals and provides a plausible explanation as to the mechanism underlying the effects observed by Linville (1985). Moreover, the newly validated integrative model provides insight into a probable mechanism for the influence that temperament (most notably perseverance) has on brooding rumination. It shows that theoretical inferences on both temperamental grounds of self-complexity and self-complexity’s potential to reduce ruminative thoughts have empirical backing. The mediation model seems to back two predictions. On the one hand, it is highly probable that high perseverance is an obstacle, hindering the development of new aspects of the self and lowering relative independence. Hence, perseverance lowers self-complexity. On the other hand, representation of the self to some extent shapes the impact of perseverance on the intensity of ruminative thoughts. That observation seems to confirm self-complexity’s role as a positive distraction from rumination. A large variation of “self” aspects seems to provide an alternative to the person being at risk of rumination. Distinct perceived life roles offer additional patterns of behavior, cognitive content and coping mechanisms, drawing the person away from inadaptive cognitive circles.

An important value of this research lies in the conclusion that higher-level cognitive representations do have the ability to alter the relation that was, up to this point, seen as rather direct and rigid. This is a vital step and a promising gateway for future research into relations between personality, cognitive representation of the self, and mood or mood disorders. Measuring self-complexity and, at the same time, taking into account temperamental traits enables observation of the effect that self-complexity has on rumination – and thus, probably, affect. This, in turn, ensures that the correlation of self-complexity with rumination is not spurious. Past research papers (e.g., Mezulis et al. 2011) often described the relationship between temperament and depression, in which rumination plays the role of mediator. However, little was said about cognitive mediators of the association between temperament and brooding rumination. This can be seen as an explanatory gap, since the relationship between temperament and rumination – being a form of complex, high-level cognition – is distant. Adding a cognitive mediator to this relationship brings these concepts closer and offers a valid explanation for the mechanism underlying brooding rumination.

Despite the positive results, the current study is not free from methodological limitations. Firstly, it should be noted that the sample group of 97 individuals from the same university might not be sufficient to obtain conclusive and reliable results. Secondly, with the existing data it is impossible to prove a causal pathway, since the current model is merely probabilistic, proposing a possible explanation for mechanisms underlying the relationship between temperament and ruminative thought. In order to determine whether self-complexity in the condition of high perseverance might cause ruminative thought, a different approach might be appropriate. The study by Nolen-Hoeksema et al. (2007) had a longitudinal structure that enabled examination of causal relations between rumination and several aspects of psychopathology, including depressive mood. This led the author to describe a web of causal pathways among the given criteria. Perhaps, through a similar design, self-complexity might be inscribed in such pathways in the future. Furthermore, a very promising future research prospect lies in including other variables in the integrative model. This would provide a possibility to explain relations between phenomena and their clinical implications in even greater depth. An especially promising direction might be seen by the introduction of age, gender and depressive symptoms or early stress data into the proposed model. However, the tool used to measure self-complexity (the SCI) has been devised to perform research on adolescents and young adults, therefore any future research would benefit from developing a version for other age groups or the general population.

References

Brausch, A. M., & Decker, K. M. (2014). Self-esteem and social support as moderators of depression, body image, and disordered eating for suicidal ideation in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(5), 779–789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9822-0.

Carter, J. D., Frampton, C., Mulder, R. T., Luty, S. E., McKenzie, J. M., & Joyce, P. R. (2009). Rumination: Relationship to depression and personality in a clinical sample. Personality and Mental Health, 3(4), 275–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.91.

Evans, D. W. (1994). Self-complexity and its relation to development, symptomatology and self-perception during adolescence. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 24(3), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02353194.

Hintsa, T., Wesolowska, K., Elovainio, M., Strelau, J., Pulkki-Råback, L., & Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. (2016). Associations of temporal and energetic characteristics of behavior with depressive symptoms: A population-based longitudinal study within Strelau's regulative theory of temperament. Journal of Affective Disorders, 197, 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.056.

Kendler, K. S., Kuhn, J., & Prescott, C. A. (2004). The interrelationship of neuroticism, sex, and stressful life events in the prediction of episodes of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(4), 631–636. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.631.

Linville, P. W. (1985). Self-complexity and affective extremity: Don't put all of your eggs in one cognitive basket. Social Cognition, 3(1), 94–120. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.1985.3.1.94.

Linville, P. W. (1987). Self-complexity as a cognitive buffer against stress-related illness and depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(4), 663–676. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.52.4.663.

Manfredi, C., Caselli, G., Rovetto, F., Rebecchi, D., Ruggiero, G. M., Sassaroli, S., & Spada, M. M. (2011). Temperament and parental styles as predictors of ruminative brooding and worry. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(2), 186–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.023.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa Jr., P. T. (1994). The stability of personality: Observations and evaluations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 3(6), 173–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10770693.

Mezulis, A., Simonson, J., McCauley, E., & Vander Stoep, A. (2011). The association between temperament and depressive symptoms in adolescence: Brooding and reflection as potential mediators. Cognition & Emotion, 25(8), 1460–1470. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2010.543642.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Stice, E., Wade, E., & Bohon, C. (2007). Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(1), 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227.

Querstret, D., & Cropley, M. (2013). Assessing treatments used to reduce rumination and/or worry: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(8), 996–1009.

Słowińska, A., Zbieg, A., & Oleszkowicz, A. (2014). Kwestionariusz Ruminacji-Refleksji (RRQ) Paula D. Trapnella i Jennifer D. Campbell-polska adaptacja metody.

Smith, J. M., Alloy, L. B., & Abramson, L. Y. (2006). Cognitive vulnerability to depression, rumination, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation: Multiple pathways to self-injurious thinking. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 36(4), 443–454. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2006.36.4.443.

Strelau, J., & Zawadzki, B. (1995). The formal characteristics of behaviour—Temperament inventory (FCB—TI): Validity studies. European Journal of Personality, 9(3), 207–229. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2410070504.

Trapnell, P. D., & Campbell, J. D. (1999). Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(2), 284–1943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2003.08.022.

Wells, A., & Papageorgiou, C. (2004). Metacognitive therapy for depressive rumination. In C. Papageorgiou & A. Wells (Eds.), Depressive rumination: Nature, theory and treatment (pp. 259–273). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd..

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by the National Science Center on the basis of decision 2017/25/B/HS6/00198.

Funding

This study was funded by Narodowe Centrum Nauki on the basis of decision 2017/25/B/HS6/00198.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Oral informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Kwestionariusz SCI D. Evansa

[SCI Questionnaire by D. Evans]

Przeczytasz za chwilę szereg scenariuszy sytuacji, które mogą przydarzyć się w codziennym życiu. Postaraj się jak najbliżej wczuć w emocje towarzyszące tym zdarzeniom.

Wyobraź sobie, że poniższe scenariusze dotyczą Ciebie i odpowiedz na pytania.

[You are about to read several scenarios, which are likely to occur in real life. Try to feel emotions that would accompany this events. Imagine, that the scenarios refer to you and answer the questions below.]

1. Będąc na przyjęciu popełniasz rażącą gafę. W związku z tym nietaktownym zdarzeniem, przez resztę wieczoru niemal nikt nie chce z Tobą rozmawiać i czujesz na sobie krytyczne spojrzenia. Jakie w związku z tym masz zdanie o sobie w poniższych dziedzinach?

[1. While attending a party, you commit an unforgivable faux-pas. After this unfortunate event, for the rest of the evening noone wants to talk to you and you feel condescending looks of other guests. What is your evaluation of yourself in listed domains?]

Znacznie gorsze niż dotychczas [much worse than before] | Nieco gorsze niż dotychczas [worse than before] | Bez zmian [no difference] | |

|---|---|---|---|

Umiejętności szkolne [academic abilities] | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Umiejętności społeczne [social abilities] | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Sprawność fizyczna [physical abilities] | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Atrakcyjność zewnętrzna [appearance] | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Kompetencja zawodowa [job competence] | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Relacje romantyczne [romantic relationships] | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Przyjaźnie [friendships] | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Prawidłowość zachowania [behaviour] | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Ogólna samoocena [general self-esteem] | 1 | 2 | 3 |

2. Na zajęciach podczas odpowiedzi powiedziałeś coś bezsensownego. Inni Studenci zaczęli się złośliwie śmiać. Następnego Dnia Masz wrażenie, że Nikt Nie Ma Ochoty z Tobą rozmawiać. Jakie W związku z Tym Masz Zdanie O Sobie W poniższych Dziedzinach?

[2. During classes, you answer a question from the lecturer and it is completely incorrect. Other students laughed at this attempt. The next day you still feel like noone wants to speak to you. What is your evaluation of yourself in listed domains?]

3. Zdarzyło się W Twoim życiu coś Bardzo Przykrego. Nie Masz Jednak Komu zwierzyć się z Tych Trudnych Dla Ciebie przeżyć. Masz wrażenie, że Nie Ma różnicy Czy Powiesz O Tym Osobie Obcej Czy Znajomemu. Jakie W związku z Tym Masz Zdanie O Sobie W poniższych Dziedzinach?

[3. Something particularly stressful happened in your life. However, you have noone to confess from these difficult experiences. You feel like there is no difference whether you tell it to a stranger or someone you know. What is your evaluation of yourself in listed domains?]

4. Podczas Treningu Ulubionego Sportu okazało się, że Znacznie spadła Twoja Forma. Nie Radzisz Sobie Ze Sportem Tak Dobrze Jak kiedyś, Czujesz Silne zmęczenie, a W Lustrze Widzisz, że pogorszyła ci się Sylwetka. Jakie W związku z Tym Masz Zdanie O Sobie W poniższych Dziedzinach?

[4. During the training of your favorite sport, it turned out, that your performance has suddenly dropped. You don’t score as high as before, feel very tired. What is more, as you look in the mirror, you notice that you don’t look as good as you used to. What is your evaluation of yourself in listed domains?]

5. Po długim zwolnieniu lekarskim wracasz do normalnych zajęć. Zauważasz jednak, że przez brak ruchu przytyłeś, łatwo się męczysz, a rozmowy ze znajomymi nie układają się tak dobrze jak dawniej.

[5. After a long medical leave you come back to normal routine. Unfortunately, you notice that due to lack of exercise you have taken up weight, become tired easily and friends you have not seen for a long time rarely talk to you. What is your evaluation of yourself in listed domains?]

6. Przypadkiem zepsułeś swój Telefon. Masz na Nim ważne zdjęcia I Pliki, a Naprawa może być Kosztowna. Jakie W związku z Tym Masz Zdanie O Sobie W poniższych Dziedzinach?

[6. You have accidentally broken your cell phone. Important files and photos might be lost and the repair will probably set you back a large sum of money. What is your evaluation of yourself in listed domains?]

7. W Ostatnich miesiącach przybrałeś/aś na Wadze. Poważnie wpłynęło to na wygląd Twojej Sylwetki, a Znajomi Czasem zwracają ci na to uwagę. Jakie W związku z Tym Masz Zdanie O Sobie W poniższych Dziedzinach?

[7. In last months you have taken up some weight and it really changed your appearance for worse. In fact, friends started to notice it and tell you about it. What is your evaluation of yourself in listed domains?]

8. Przypadkiem usłyszałeś/aś rozmowę Swoich Znajomych z Klasy. Potajemnie mówią O Tobie. Z Rozmowy Wynika, że uważają Cię Za osobę nieprzyjazną, bezczelną I Niezbyt inteligentną. Postanawiają, że będą unikać spotkań z Tobą. Jakie W związku z Tym Masz Zdanie O Sobie W poniższych Dziedzinach?

[8. You have coincidentally overheard conversation between two of your classmates. They talk about you secretly. From what you heard it turns out that they find you as an unfriendly, brash and not really intelligent person. They agreed that they will avoid meeting you. What is your evaluation of yourself in listed domains?]

9. Jesteś na randce w restauracji. Kelnerka wylała na Ciebie kolorowy napój. Osoba z którą jesteś dziwnie się uśmiechnęła. 15 minut później “wyszła do toalety” i nie wróciła.

[9. You are on a date in a restaurant. The waitress spilled a coloured drink on you. Your date smirked weirdly. 15 min later headed “to the toilet” and never went back to meet you. What is your evaluation of yourself in listed domains?]

10. W Pracy Powierzono ci ważne Zadanie. Jest Ono Jednak Dla Ciebie na Tyle Trudne, że Zajmuje ci Znacznie więcej Czasu niż na Nie Przewidziano, a przełożony Jest Niezadowolony Poziomem Jego Wykonania, Dostrzega W Nim Liczne błędy. Spotykasz się z Krytycznymi Komentarzami na Temat Swojego wykształcenia I uważności W Pracy. Jakie W związku z Tym Masz Zdanie O Sobie W poniższych Dziedzinach?

[10. You were given an important to complete at work. It took you much more time than you expected and your boss isn’t satisfied with the results, pointing to several errors you made, followed by commentaries about your lack of education and attentiveness at work. What is your evaluation of yourself in listed domains?]

11. Otrzymałeś niższe Oceny z Matury niż się spodziewałeś, Przez Co Nie dostałeś się na Wymarzony Kierunek studiów. Jakie W związku z Tym Masz Zdanie O Sobie W poniższych Dziedzinach?

[11. Your final exams came back with much worse marks than you predicted. Because of that, you won’t be able to apply for your dream faculty. What is your evaluation of yourself in listed domains?]

12. Osoba, którą Darzysz Uczuciem Nie wyraża Zainteresowania bliższą relacją z Tobą, Nie przyszła na z Trudem umówione Spotkanie. Jakie W związku z Tym Masz Zdanie O Sobie W poniższych Dziedzinach?

[12. The person you feel strong feelings to isn’t interested in a relationship with you and has not showed up for a meeting you have effortfully arranged. What is your evaluation of yourself in listed domains?]

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Czarnocki, M., Imbir, K.K. Self-complexity mediates the relationship between temperamental perseverance and ruminative thoughts. Curr Psychol 41, 2919–2926 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00808-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00808-y