Abstract

The Global Motivation Scale (GMS) is an 18-item self-report questionnaire. It measures a multidimensional conceptualization of motivation that falls along the self-determination continuum. The aim of the study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Polish version of the GMS, and to investigate its structure and reliability in a group of 537 subjects, aged 18–86 (M = 36.19; SD = 15.20). The bifactor modelling didn’t validate the theoretical six-factor model of the GMS, thus an exploratory analysis was conducted to determine an optimal model across age, gender and education. The adopted four-factor model matched three original GMS subscales: intrinsic motivation, external regulation and amotivation; the fourth factor represented identified and integrated regulations simultaneously (introjected regulation wasn’t included). Correlations among the factors didn’t confirm the simplex pattern, while the composite reliability coefficients were low (.55–.66). It is insufficient to analyze the assessment of the self-determination continuum only for statistical correctness – linguistic and cultural contexts should also be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan and Deci 2000) proposes a personality model based on human needs to feel competent, autonomous, and related to others. Since the theory is related to the concepts of positive psychology and social cognitive theory, it is ever more often utilized in empirical studies to explain and predict human actions. Despite considerable progress of research in this field, new challenges still emerge, concerning both the conceptualization and the measurement of regulatory processes in SDT (e.g., Boiché et al. 2008; Mallett et al. 2007).

Motivation in the Perspective of Self-Determination Theory

SDT proposes a multidimensional conceptualization of motivation comprising three forms of motivation: intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation and amotivation which in total comprise six regulatory orientations (Deci and Ryan 2000; Ryan and Deci 2000). Intrinsic motivation occupies the self-determination continuum pole where regulatory processes are related to inner personal characteristics of agency. Its basic function is to organize human activity aimed at achieving a self-set goal (e.g., excelling at a sport, working with a talented student). Intrinsic motivation refers to engaging in certain activities because of the inherent enjoyment and inherent satisfaction derived from performing them. Extrinsic motivation is situated at the midpoint of the self-determination continuum. It contains four types of regulatory orientation which reflect interiorization based on the development of processes that organize and direct a problem which result in the growth of related competences and abilities. Each of the four types of regulation, with their separate sources, influences an action in a different way. The highest level of self-determination is followed by: integrated regulation (behavior is adjusted to other activities and aims at life resulting from values), identified regulation (behavior is valued and perceived as being chosen by the individual itself), introjected regulation (behavior is controlled internally, but the way it is directed is borrowed from the exterior), external regulation (activity is stimulated externally by awards and limitations). The other end of the continuum is occupied by amotivation characterized by the lack of willingness to perform a task, excessive discouragement, and apathy. Amotivation represents the nonregulated extreme end of the self-determination continuum.

The mutual relationships between the forms of regulation and their levels of generality within the individual are reflected by the Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation (HMIEM; Vallerand 1997; Vallerand and Ratelle 2002), an expanded variant of SDT. This model postulates an interactional approach, according to which intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are not independent, and a high level of one kind of regulation is necessarily linked to a low level of the other. This assumption is explained by the so-called simplex pattern, according to which correlations between adjacent forms of regulation on the self-determination continuum would be stronger and positive compared to correlations between more distant form of regulations, which would be expected to be negative. Additionally, HMIEM places motivation at three levels of generality (Vallerand 1997), which are: global motivation (a broad general motivational tendency to interact with the environment), contextual motivation (a general motivation toward a specific context or life domain) and situational motivation (or a state motivation: the motivation an individual experiences toward a given activity at a specific time). According to the HMIEM, there is an interaction between the levels of generality, which leads to two kinds of effect, called “top-down” and “bottom-up”. The top-down effect indicates that motivation at a higher level of generality may exert influence on a lower level, while the bottom-up one is a recursive effect in some related activities (Lavigne and Vallerand 2010). When people feel self–determined toward their lives in general, they should demonstrate a broad tendency to initiate and regulate their behaviors through choice and act in accordance with their own values. General self–determination could be a protector against sociocultural pressures related to body image (Pelletier and Dion 2007) or a predictor of motivation to change risk behaviors among patients with chronic diseases (Życińska et al. 2012).

Measuring Motivation: Challenges in the Self-Determination Perspective

Motivation is most often defined by means of determining its sources and effects (Guay et al. 2000). Hence, the basic problem in the process of SDT operationalization lies in the construction of tools that would measure motivation and not its sources or effects of the action itself. Such approach has one unquestionable advantage: the sources of motivation processes can be monitored by psychological processes, e.g., the needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness (Vallerand 1997), whereas the effects of action undergo cultural evaluation. If the effects of action are ignored, it is possible to construct a trans-cultural tool for motivation assessment.

This task seems relatively simple to tackle, in comparison with the operationalization of the self-determination continuum. However, several aspects are worth emphasizing here.

Firstly, it is unjustified to construct tools measuring only one form of regulation, disregarding other forms (see Guay et al. 2000). Items measuring integrated regulation, which is a form of extrinsic motivation, are most often omitted. The reasons given for deleting them are e.g., a young age of the examined subjects (Baldwin and Caldwell 2003; Stover et al. 2012), the economic aspect of assessment (Guay et al. 2000) or difficulties with wording items in terms of their face value as it often equals overlapping with identified and intrinsic motivation subscales (Gagné et al. 2015).

Secondly, it is necessary to determine the possible dependences between individual forms of regulation (Boiché et al. 2008), for example according to the aforementioned HMIEM (Vallerand 1997). Results of numerous empirical studies confirm the interactional approach in several domains (e.g., Pelletier et al. 1995; Paic et al. 2017). A significant number of such studies, however, at least concerning the dependences between selected forms of regulation, do not reflect the simplex pattern (e.g., Cokley 2000; Covington and Muëller 2001; Fairchild et al. 2005; Smith et al. 2010; Tsorbatzoudis et al. 2006). The obtained discrepancies may result from erroneous theoretical assumptions and specific conditions (e.g., the age of subjects examined – see Baldwin and Caldwell 2003). This statement may only be verified once the tools are correctly validated, which presents yet another challenge.

Thirdly, from the research quality point of view, the multidimensional structure of the self-report measures should be verified by bifactor exploratory structural equation modeling (Howard et al. 2018; Sheldon et al. 2017) in the studies on groups with possibly highest diversity (e.g., due to age, gender, education, kind of activity and culture) - cf. Mallett et al. 2007. The results of studies concerning factor structure validation of the tools measuring motivation in the SDT perspective are not cohesive (e.g., Chatzisarantis et al. 2003). A review made by Mallett et al. (2007) related to the six-factor Sport Motivation Scale (SMS-6) is an example of the way a tool measuring contextual level can be evaluated. Out of the eight analyzed studies, in which confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used, only two specifically supported the structure of this scale. The meta-analysis based on data from 486 samples derived from the use of thirteen validated scales also measuring contextual level of motivation largely supported a self-determination continuum. Results did not support the inclusion of integrated regulation or conceptualizing intrinsic motivation as multidimensional (i.e. intrinsic motivation to know, to experience stimulation, and to achieve) due to excessively high inter-factor correlations and overlapping confidence intervals (Howard et al. 2017). Results concerning situation measurement (e.g., the Situational Motivation Scale, SIMS; Guay et al. 2000) are more promising. However, their global goodness-of-fit indices were marginally acceptable according to conventional cut-off points.

Aims of the Study

Considering the previously mentioned requirements for self-report measures of the motivation in SDT perspective, one may state that the Global Motivation Scale (GMS) meets them all: it contains all types of regulation (intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation by integrated, identified, introjected and external regulation, and amotivation) at a global level, it serves to examine adults, and - in the studies conducted among English-speaking individuals (American and Canadian samples) – the six-factor structure of self-determination continuum was supported, levels of internal consistency were satisfactory (all α > .73) and temporal reliability was acceptable (.72) over a six-week period (Pelletier et al. 2007; Sharp et al. 2003).

In view of the enumerated challenges, the present study aims at replicating the latent structure of the GMS responses in a sample of Polish-speaking individuals and further examination of the scale reliability and the factor model structure in groups according to age, gender and education.

It was hypothesized that the Polish version of the GMS (a) would be represented by a multidimensional 6-factor structure reflected by the types of regulation, (b) interfactor correlations would correspond to a simplex pattern (correlations between adjacent subscales on the self-determination continuum would be stronger and positive compared to correlations between more distant subscales, which would be expected to be negative), and (c) would be invariant across age, gender and education of participants.

Methods

Participants

A total of 537 subjects were examined, including 325 females (60.5%), aged 18–86 (M = 36.19; SD = 15.20) for GMS structure validation. The subjects had secondary school education (44.7%), university education (32.83%), or elementary and basic vocational education (22.5%). Like gender and education, age was also used as a moderator in further analyses. The participants were divided into three subgroups, taking into account the consecutive stages of adulthood (see Brzezińska et al. 2008), which were: early adulthood - 317 subjects, 18–35 years of age, (59.0%; age: M = 25.49, SD = 4.73); intermediate adulthood - 192 subjects, 36–65 years of age (35.8%; age: M = 48.52, SD = 8.29), while the last and least numerous group comprised merely 28 subjects above the age of 65 (5.2%; age: M = 72.68, SD = 5.50).

The data were collected by trained interviewers supervised by researchers. The interviewers recruited each subject via their social contacts, preserving anonymity of the subjects. The study excluded individuals in difficult life situations or undergoing psychiatric treatment. Steps were taken to ensure that the examined group was representative of the population in terms of sex, age and education.

Polish Version of the General Motivation Scale

The Global Motivation Scale (GMS) was first developed by Sharp et al. (2003) and it was adapted to measure six types of regulation in the self-determination continuum, as defined by Deci and Ryan (2000). The GMS versions included between 18 and 28 items (see: Pelletier et al. 2004a– another name of the tool: General Self-Determination Scale; Pelletier et al. 2004b; Pelletier and Dion 2007 – the 24-item version – in these studies a general self-determination index was calculated). The three subscales to measure the types of intrinsic motivation: toward knowledge, stimulation, and accomplishment were included only in selected studies (e.g., Guay et al. 2003 – the 28-item version). The 18-item version of the scale used in this study was obtained directly from its lead author, Pelletier. All the items began with: In general, I do things … followed by the various reasons for which people perform their different life activities, such as: … for the pleasure of learning something new (intrinsic motivation); ... because they represent who I am (integrated regulation); ... in order to help myself become the person I aim to be (identified regulation); ... because otherwise I would feel guilty for not doing them (introjected regulation); ... because I do not want to disappoint certain people (external regulation); and ... even though I do not see the benefit in what I am doing (amotivation). The response format was a seven-point rating scale ranging from 1 – not agree at all to 7 – completely agree.

The Polish language version of the GMS was developed according to the adaptation principles of intercultural studies (including patient-reported measures of outcomes; Wild et al. 2005). A team of three translators was assembled to ensure the highest fidelity of translation, including the translating supervisor - the coauthor of this study, a person knowledgeable in methodology and the SDT. During the first stage, the GMS was translated into Polish by the team of translators. Then the so-called monolingual team, consisting of 4 persons (two females and two males with elementary education and not speaking English) evaluated the translation, after which certain corrections were introduced into the GMS. During the next stage a professional translator made a back-translation. There were no differences between the original and the backtranslated versions.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis – Construct Validity

The 6-factor structure of the GMS was verified by means of the CFA with a Confirmatory Bifactor Modelling (CBM). The CBM model is better suited to the GMS structure, which consists of a general factor and six subscales: intrinsic motivation, integrated regulation, identified regulation, introjected regulation, external regulation and amotivation (cf. Howard et al. 2018; Reise et al. 2010; Sheldon et al. 2017).

The obtained factor loadings (see Fig. 1) in many cases are low, both in case of the general factor as well as in the subscales. As regards the general factor, the relatively high loadings are observed only in case of items 2 and 3 – in the remaining cases the loadings do not exceed the value of 0.6. It is also worth noting that the general factor indicates the weakest relationship with the items belonging to the following subscales: introjected regulation, external regulation and amotivation (the loadings do not exceed the value of 0.4, in case of item 13 the value is negative).

In case of the subscales, none obtained high loadings for each factor. Even though some subscales (intrinsic motivation, external regulation, amotivation) may be referred to as relatively strong as regards the value of the loadings (the minimal value does not fall below 0.39), the remaining subscales have at least one low loading: < 0.3 (the worst cases being the integrated regulation and identified regulation subscales, where two out of three loadings are low).

The CFA results showed an insufficient fit of this model to the data (c.f. Bollen and Stine 1992; Browne and Cudeck 1993; Hu and Bentler 1999): χ2(109) = 399.51; p < 0.001; χ2/df = 3.67; root mean square residual, RMR = 0.21 (Standardized RMR = 0.06); Goodness-of-fit Index of Jöreskog & Sörbom, GFI = 0.92; Adjusted Goodness-of-fit Index of Jöreskog & Sörbom, AGFI = 0.88; Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index, CFI = 0.84; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, RMSEA = 0.07; Tucker-Lewis Index TLI = 0.78 (also known as Bentler-Bonett Nonnormed Fit Index, NNFI); Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index, NFI = 0.80.

Next, using the results of all the 18 GMS items, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with varimax rotation and maximum-likelihood estimation procedures was conducted to explore the factor structure. The Kaiser-Guttman criterion (see Yeomans and Golder 1982) indicated a five-factor structure as an optimal solution. However, the analysis of the scree plot and the percentage of variance explained by consecutive factors suggested an “elbow” at roughly four-factors structure which became an assumption for the next CFA analysis. Table 1 provides the EFA results (the four-factor variant). The obtained structure is not consistent with the self-determination continuum: only the second factor’s items are fully consistent with the original subscale - amotivation. Other factors include items assigned to various subscales and require redefinition. The explained variance level for each factor ranges from 6.9% to 11.7% and is quite low, so is the total variance, which equals 33.3%.

The factor structure obtained by EFA was further verified using CFA. The analyzed model was reduced to items with factor loadings greater than or equal to 0.4 in EFA. The first factor consisted of items 14, 16, 7, 18, and 11, the second – of items 4 and 15; third – of items 5, 12, 1, and 8; and the last one – of items 3 and 2. The four-factor CFA in the first step did not provide a statistically satisfactory fit. Satisfactory fit indices for a four-factor model of the GMS were only obtained after removal of certain items showing significant correlations/covariates with items from other factors or one of the factors, according to the modification indices.

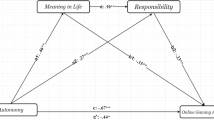

The items for each factor, the factor loadings, the factor intercorrelations and fit statistics are included in Fig. 2. The interpretation of fit statistics proved to be a hard task. On the one hand, the hypothesis of exact fit of the model has not been confirmed: χ2 (21, N = 537) = 52.23; p < 0,001 (χ2/df ratio is still below 3, which according to less stringent, old criteria [c.f. Wheaton et al. 1977] is still acceptable; GFI and AGFI are high). On the other hand, non-centrality-based indices like RMSEA (=.05 with 90% UCL = .07), and CFI (=.96) nearly or exactly meet the generally accepted criteria. Relative fit indices (NFI, TLI) are on a moderate level: they exceed 0.90 but it is not enough to meet the current demands for such fit indices (c.f. Bollen and Stine 1992; Browne and Cudeck 1993; Hu and Bentler 1999).

Statistical significance of the model parameters was estimated using confidence intervals obtained using a sampling method (“bootstrap sampling” with 1000 samples; 95% BC confidence intervals). All but one factor loadings and intercorrelations shown in Fig. 2 indicate statistical significance determined by the corresponding confidence interval. The only exception is the correlation between the first and the second factor - in this case an appropriate confidence interval includes the value of 0 within its scope.

An evaluation of the four-factor model of the GMS in terms of fit statistics may evoke some controversy, depending on which statistics are taken into account. Neither the assessment of the level factor loadings nor their number raise similar concerns: they are relatively low (ranging from 0.48 to 0.74) and only factor 1 consists of three items – the remaining ones have only two items each. A low number of items per one factor is primarily a result of working on the final version of the tool and not on the pilot one, which had a small number of items attributable to a subscale.

In terms of content, the four-factor model of the GMS may be considered consistent with the original structure of the tool, because factor 1 comprises of items 7, 11 and 14, which correspond to the intrinsic motivation subscale; factor 2 has two items (1 and 5) from the external regulation subscale while, in case of factor 3, items 4 and 15 form the amotivation subscale. Only factor 4 has items that originally corresponded to two different subscales (located next to each other on the self-determination continuum): 2 - identified regulation and 3 - integrated regulation (see Table 2).

Nevertheless, the correlations between the four subscales do not represent the simplex pattern (see Fig. 2). For example, the correlation between intrinsic motivation (factor 1) and amotivation (factor 3) is r = .55, p = .001, and its strength is the same as for the correlation of identified and integrated regulations (factor 4), which is r = .54, p = .003. This means that the level of correlation is the same between intrinsic motivation and its adjacent forms in the continuum of self-determination (i.e. identified and integrated regulations), as well as between amotivation, which is the opposite set of regulatory processes. Given the assignment of items to factors and inter-correlations between them, it cannot be concluded that the structure of the GMS has been confirmed.

As previously mentioned, despite the acceptable level of fit statistics of the four-factor GMS model, its has weak points such as small number of items per one factor and low factor loadings. It is hardly surprising, then, that the final scale is characterized by a low composite reliability (Ωw - cf. Bacon et al. 1995): factor 1 (intrinsic motivation) - .60, factor 2 (external regulation) - .59, factor 3 (amotivation) - .55 and factor 4 (identified and integrated regulations) - .66.

Four-Factor Model of the GMS across Gender, Age and Education

Additional CFA analyses were conducted in order to monitor changes in the structure of the four-factor model of the GMS in groups by age, gender and education (results are shown in Table 3). We concluded that none of those variables had any effect on the structure of the GMS. The obtained four-factor model appears to be independent from them. This statement must be accepted, with two reservations, however. First, the model with groups arranged by gender has the weakest fit indices. Secondly - the model with groups divided by age does not include the group of oldest subjects, which was not large enough to perform calculations.

Discussion

The results of the GMS exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses demonstrated that the multidimensional six-factor model based on the self-determination theory does not fit the data. The four-factor model, after rejection of items correlated with other factors or with items from other factors, proved to be best suited to the data. The three factors correspond to the original structure of the GMS: intrinsic motivation, external regulation and amotivation. The fourth factor represents two types of regulation simultaneously, i.e. identified and integrated regulations, whereas introjected regulation was not included in the model. The values of factor loadings for separate items are considerably low. This – and a low number of items per factor – results in low subscale reliability coefficients. The obtained four-factor structures do not change in groups according to gender, age and education of the participants.

Mallett et al. (2007) indicated similar problems while verifying the Sport Motivation Scale (SMS, Pelletier et al. 1995), an affined version of GMS. Referring to the results of six studies, which evaluated only the English version of the questionnaire, one can easily observe that the structure of the tool was not confirmed in them, which was a result of low factor loadings of separate items. Consequently, the number of regulation types examined had to be reduced while SMS was used only in selected groups of sportsmen (the tool structure was not resistant to age of the examined sportsmen - it was not confirmed in the senior group). According to Mallett et al. (Mallett et al. 2007; Kawabata and Mallet 2013), it was caused by the way the scale items were worded.

It is worth noting that the analysis of the Polish GMS version produced a different outcome in comparison with the results contained in literature for several reasons. Firstly, the obtained goodness-of-fit indices of four-factor model of the GMS are more adequate, while most of them meet the strict statistical criteria. Secondly, the study was conducted on subjects from general population, representing various levels of education and all adulthood stages.

As it was discussed before, the reliability indicators for the GMS psychometric values were very low. The assumptions of the HMIEM (Vallerand 1997; Vallerand and Ratelle 2002) especially the simplex pattern were not confirmed, either. These results may of course, as before, be explained at the level of the questionnaire items (or, more precisely, their inadequate wording in relation to the theory and their insufficient number). One may also, however, refer to the arguments proposed by Boiché et al. 2008, concerning the practicality of using a cluster analysis that makes it possible to isolate individuals that do not fit this pattern. In these studies (also in the study carried out by Ntoumanis 2002), concerning physical education, three possible profiles were suggested to combine different types of motivation proposed by SDT, two of which supported the interaction approach. The most interesting was the third profile, for which the average results were obtained in relation to all the regulation forms. Attention should be directed to the fact that the mean level of motivation could mean both positive and negative effects, in the form of performance of gymnastics and obtained grades. It turned out that a significant factor explaining this phenomenon were the sources of motivation, e.g., certain satisfaction from the activity or expectation that the activity would help the subject reach personal goals.

This leads to the conclusion that it is not enough to analyze the assessment of the self-determination continuum only for the sake of correctness of statistical analyses. The tendency to examine motivation in the perspective of SDT, without the integrally related sources of regulatory processes and the evaluation of the achieved results, should be thoroughly discussed. It is especially important in case of intrinsic motivation, since it may have its source in acquiring knowledge, obtaining stimulation or performing the action itself (Vallerand 1997; Vallerand et al. 1992). As far as intrinsic motivation goes, the aim itself is not important. However, when extrinsic motivation is evaluated, the process of striving to achieve one’s aim is most decisive for the level of execution. If one kind of motivation is decisively effective (e.g., rewards), then examining the whole continuum obscures the real motivation for taking action. According to SDT, one may also imagine that several aims are being followed simultaneously, even in the sphere of one specific domain (e.g., a sportsman wants to achieve good sports results, but he also wants to maintain a high standard of living for his family), or that several kinds of motivation combine to secure one specific aim (e.g., it is important to experience symptoms sent from the body that indicate fatigue, but also its significant capabilities; one may experience satisfaction while discussing the issue with others during a training session).

Another important problem, rarely studied in research projects, is the use of stage theories in the assessment of achieving an aim (cf. Sutton 2000). Stage theories assume that behaviour change is a process that involves movement through at least two distinct stages (e.g., Health Action Process Approach, HAPA; Schwarzer 2008). The first stage relates to motivational processes, where an individual makes a decision concerning a change. The other stage regards volitional processes, where this behavior is practiced, and maintained until it becomes a habit. Motivation may assume different forms, depending on the stage (e.g., TSRQ: motivation to engage in or change a health behaviour), and additionally on the relation between driving towards an aim and the needs of an individual. It turns out, for example, that if the motivation for change is weak, then the stimulation of intrinsic motivation is not possible; it only occurs at an average intensity (Levesque et al. 2007). The type of stage in the process of change is rarely controlled in studies considering motivation. It may also be assumed that some disturbances (or, more specifically, psychical states, such as depression) may generate a state of amotivation (Guay et al. 2000), as to which there is general disagreement whether amotivation marks the start of self-determination continuum or whether it is an independent process.

The last but not least, conclusion related to linguistic and cultural differences that could affect the psychometric properties of adapted tools to measure self-determination continuum should be drawn. As pointed in the introduction, if the effects of action are ignored, it is possible to construct a trans-cultural tool for motivation assessment. Nevertheless, the validation difficulties were related to the Turkish (Ünal Karagüven 2012) and the Spanish (cf. Stover et al. 2012) versions of the Academic Motivation Scale (AMS; Vallerand et al. 1992), the affined version of the GMS. Because of some controversies regarding to existing versions of the AMA in Spanish, the specific version of this scale was developed for Latin-American population. For example, the terms such as “pleasure”, “satisfaction” or “feel guilty” were replaced by terms with neutral connotation, some items were removed or reworded, as well as the seven-point Likert scale was reduced to a four-point one (Stover et al. 2012). The Iranian version of the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire-2 (Farmanbar et al. 2011), as well as the Greek version (Moustaka et al. 2010) and the Spanish one (Murcia et al. 2007) were also modified to improve content and construct validity. Controversies related to dimensionality of the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (TSRQ; Ryan and Connell 1989) were found out during the Polish adaptation among patients with chronic diseases (Życińska et al. 2012). To sum up, the present Polish version of the GMS should be developed to consult cultural context of measuring motivation in self-determination perspective.

Limitations of the Study

It must be underlined that only six-factor CFA analyses, whose models reflect the structure of the original tool, have a strictly confirmatory status. All of the other analyses were based on either exploratory versions of a factor analysis or on modification indices. The introduction of EFA results at the start of CFA or changes resulting from the modification indices are tantamount to a breach of the CFA orthodox principles. It has its origin in the limitations resulting from post-pilot analyses; these are the authors that determine the theoretical framework, which should not be overstepped, even despite strong arguments.

The specific character of analyses of the post-pilot version tools poses yet another problem. In pilot conditions, it is always possible to update the scale, adding the missing items according to the most optimal CFA-obtained structure. Assuming this study is of adaptive character, i.e. it is used to evaluate a fully prepared tool, updating the scale was out of the question.

The demographic structure of the examined subjects is also of interest. Despite the fact that no effort was spared to render the study more representative than earlier research, the lack of sufficient number of subjects above the age of 65 was of big importance. EFA and correlation matrixes suggest that it is this group that has a different GMS factor image, in comparison to other age groups. The low number of subjects in this group, however, made it impossible to include it in the CFA.

References

Bacon, D., Sauer, P., & Young, M. (1995). Composite reliability in structural equations modeling. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 55(3), 394–406.

Baldwin, C. K., & Caldwell, L. L. (2003). Development of the free time motivation scale for adolescents. Journal of Leisure Research, 35, 129–151.

Boiché, J. C. S., Sarrazin, P. G., Grouzet, F. M. E., & Pelletier, L. G. (2008). Student’s motivational profiles and achievement outcomes in physical education: A self-determination perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 688–701.

Bollen, K. A., & Stine, R. A. (1992). Bootstrapping goodness-of-fit measures in structural equation models. Sociological Methods and Research, 21, 205–229.

Browne, M.W. , Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. W: K.A. Bollen, J.S Long (red.), Testing structural equation models (s. 136–162). Newbury Park: Sage.

Brzezińska, A. I., Appelt, K. i Ziółkowska, B. (2008). Psychologia rozwoju człowieka [Psychology of Human Development]. W: J. Strelau, D. Doliński (red.), Psychologia. Podręcznik akademicki [Psychology, A University Textbook] (t.2, s. 95–292). Gdańsk: Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne.

Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., Hagger, M. S., Biddle, S. J. H., Smith, B., & Wang, J. C. K. (2003). A meta-analysis of perceived locus of causality in exercise, sport, and physical education contexts. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 25, 284–306.

Cokley, K. O. (2000). Examining the validity of the academic motivation scale by comparing scale construction to self-determination theory. Psychological Reports, 86, 560–564.

Covington, M. V., & Muëller, K. J. (2001). Intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation: An approach/avoidance reformulation. Educational Psychology Review, 13, 157–176.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The what and why of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Fairchild, A. J., Horst, S. J., Finney, S. J., & Barron, K. E. (2005). Evaluating existing and new validity evidence for the academic motivation scale. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 30, 331–358.

Farmanbar, R., Niknami, S., Hidarnia, A., & Lubans, D. R. (2011). Psychometric properties of the Iranian version of the behavioral regulation in exercise questionnaire-2 (BREQ-2). Health Promotion Perspectives, 1(2), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.5681/hpp.2011.010.

Gagné, M., Forest, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Crevier-Braud, L., Van den Broeck, A., et al. (2015). The multidimensional work motivation scale: Validation evidence in seven languages and nine countries. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24, 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2013.877892.

Guay, F., Vallerand, R. J., & Blanchard, C. (2000). On the assessment of situational intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The situational motivation scale (SIMS). Motivation and Emotion, 24, 175–213.

Guay, F., Mageau, G., & Vallerand, R. J. (2003). On the hierarchical structure of self-determined motivation : A test of top-down and bottom-up effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 992–1004.

Howard, J. L., Gagné, M. & Bureau, J. S. (2017). Testing a continuum structure of self-determined motivation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin , 143(12), 1346–1377. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000125.

Howard, J., Gagné, M., Morin, A. J. S., & Forest, J. (2018). Using Bifactor-exploratory structural equation modeling to test for a continuum structure of motivation. Journal of Management, 44, 2638–2664. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316645653.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Controventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

Kawabata, M., & Mallet, C. J. (2013). Examining discriminant validity issues of the sport motivation scale 6. Journal of Sport Sciences, 31, 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.723132.

Lavigne, G. L., & Vallerand, R. J. (2010). The dynamic processes of influence between contextual and situational motivation: A test of the hierarchical model in a science education setting. Journal of Applied Psychology, 40, 2343–2359.

Levesque, C. S., Williams, C. G., Elliot, D., Pickering, M. A., Bodenhamer, B., Finley, P. J. (2007). Validating the theoretical structure of the treatment self-regulation questionnaire (TSRQ) across the different health behaviors. Health Education Research, 5, 691–702.

Mallett, C., Kawabata, M., & Newcombe, P. (2007). Progressing measurement in sport motivation with the SMS-6: A response to Pelletier, Vallerand, and Sarrazin. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 8, 622–631.

Moustaka, F. C., Vlachopoulos, S. P., Vazou, S., Kaperoni, M., & Markland, D. (2010). Initial validity evidence for the Behavioural regulation in exercise questionnaire – 2 among Greek exercise participants. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(4), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000036.

Murcia, J. A., Gimeno, E. C., & Camacho, A. M. (2007). Measuring self-determination motivation in a physical fitness setting: Validation of the behavioral regulation in exercise questionnaire-2 (BREQ-2) in a Spanish sample. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 47(3), 366–374.

Ntoumanis, N. (2002). Motivational clusters in a sample of British physical education classes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 3, 177–194.

Paic, R., Kajos, A., Meszler, B., & Prisztóka, G. (2017). Validation of the Hungarian sport motivation scale (H-SMS). Cognition, Brain, Behavior, 21, 275–291. https://doi.org/10.24193/cbb.2017.

Pelletier, L. G., & Dion, S. (2007). An examination of general and specific motivational mechanisms for the relationships between body dissatisfaction and eating behaviors. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26, 303–333.

Pelletier, L. G., Fortier, M. S., Vallerand, R. J., Tuson, K. M., Brière, N. M., & Blais, M. R. (1995). Toward a new measure of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation in sports: The sports motivation scale (SMS). Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17, 35–53.

Pelletier, L. G., Dion, S., Slovinec-D’Angelo, M., & Reid, B. (2004a). Why do you regulate your eating behaviors? Relationships between forms of regulation, eating behaviors, sustained dietary change, and psychological adjustment. Motivation and Emotion, 28, 245–277.

Pelletier, L. G., Dion, S., & Séguin-Lévesque, C. (2004b). Can self-determined motivation help protect women against socio-cultural influences about body image and reduce their risk of experiencing bulimic symptoms? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 61–88.

Pelletier, L. G., Sharp, E., Blanchard, C., Lévesque, C. Vallerand, R. J., & Guay, F. (2007). The general motivation scale (GMS): Its validity and usefulness in predicting success and failure at self-regulation. Manuscript in preparation. University of Ottawa.

Reise, S. P., Moore, T. M., & Haviland, M. G. (2010). Bifactor models and rotations: Exploring the extent to which multidimensional data yield univocal scale scores. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(6), 544–559.

Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 749–761.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

Schwarzer, R. (2008). Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57(1), 1–29.

Sharp, E., Pelletier, L. G., Blanchard, C., & Levesque, C. (2003). The global motivation scale: Its validity and usefulness in predicting success and failure at self-regulation. Los Angeles: Paper presented at the Society for Personality and Social Psychology.

Sheldon, K. M., Osin, E. N., Gordeeva, T. O., Suchkov, D. D., & Sychev, O. A. (2017). Evaluating the dimensionality of self-determination theory's relative autonomy continuum. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 43, 1215–1238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217711915.

Smith, K. J., Davy, J. A., & Rosenberg, D. L. (2010). An examination of the validity of the academic motivation scale with a United States business student sample. Psychological Reports, 106, 323–341.

Stover, J. B., de la Iglesia, G., Boubeta, A. R., & Liporace, M. F. (2012). Academic motivation scale: Adaptation and psychometric analyses for high school and college students. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 5, 71–83. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S33188.

Sutton, S. (2000). Interpreting cross-sectional data on stages of change. Psychology and Health, 15, 163–171.

Tsorbatzoudis, H., Alexandris, K., Zahariadis, P., & Grouios, G. (2006). Examining the relationship between recreational sport participation and intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and amotivation. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 103, 363–374.

Ünal Karagüven, M. H. (2012). The adaptation of academic motivation scale to Turkish. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 12(4), 2611–2618.

Vallerand, R. J. (1997). Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 29, pp. 271–360). New York: Academic Press.

Vallerand, R. J., & Ratelle, C. F. (2002). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: A hierarchical model. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 37–69). Rocheste: University of Rochester Press.

Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Briere, N. M., Senécal, C., & Vallierès, E. F. (1992). The academic motivation scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52, 1003–1017.

Wheaton, B., Muthén, B., Alwin, D., & Summers, G. (1977). Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. In D. R. Heise (Ed.), Sociological methodology (Vol. 8, p. 84). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, Inc..

Wild, D., Grove, A., Martin, M., Eremenco, S., McElroy, S., Verjee-Lorenz, A., & Erikson, P. (2005). Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value in Health, 8, 94–104.

Yeomans, K. A., & Golder, P. A. (1982). The Guttman- Kaiser criterion as a predictor of the number of common factors. The Statistician, 31(3), 221–229.

Życińska, J., Januszek, M., Jurczyk, M., & Syska-Sumińska, J. (2012). How to measure motivation to change risk behaviours in the self-determination perspective? The polish adaptation of the treatment self-regulation questionnaire (TSRQ) among patients with chronic diseases. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 43(4), 261–271.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zycinska, J., Januszek, M. How to measure the self-determination continuum? Initial validity evidence for the polish version of the Global Motivation Scale (GMS). Curr Psychol 40, 2211–2220 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-0145-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-0145-3