Abstract

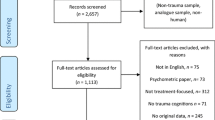

The paper presents the Polish version of the Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory developed by Foa and colleagues Psychological Assessment, 11(3), 303–314 (Foa et al., 1999). The scale measures three types of cognitions that are typically associated with traumatic experiences: negative cognitions about the self, negative cognitions about the world, and self-blame. The scale was translated to Polish using a forward – backward translation method; it was administered to a group of adult Polish women from the general population. A total of 337 individuals participated in the project. Traumatic experiences of sexual and non-sexual type were assessed and separate analyses were conducted for cognitions related to trauma of non-sexual and sexual nature. Moreover, the cumulative trauma and the severity of symptoms of the posttraumatic stress disorder were measured. Reliability of all scales was proven to be very good, with Cronbach-α for all scales above.80. There was a positive correlation between all three types of posttraumatic cognitions and (1) severity of the PTSD symptoms, (2) number of different traumatic events. The results of the current study provided partial support for the three factor structure of the tool: three factors emerged in exploratory factor analyses, but the correlations between the subscales were very high. Also, confirmatory factor analyses did not support the original solution. Overall, the Polish version of the PTCI has good psychometric properties and can be used in research, considerable evidence to support the three factor solution was also found.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Cognitive models of the psychological reaction to trauma are based on the assumption that the subjective appraisal of an event has effect on the response to trauma and the severity of trauma related symptoms (Ehlers and Clark 2000); and that negative posttraumatic cognitions mediate the relationship between exposure to trauma and psychopathology. There is vast evidence suggesting that individuals exposed to trauma often develop negative beliefs about themselves and the world (Foa and Riggs 1993; Foa and Rothbaum 1998; Artime and Peterson 2015) – this seems to apply mostly to individuals who lack social support and personal resources to deal with trauma (Zang et al. 2017). Holding negative views about oneself is, in turn, associated with higher severity of psychiatric symptoms related to trauma – such as posttraumatic stress disorder or generalized anxiety disorder (Samuelson et al. 2016; Beck et al. 2015). In a study conducted by Barton et al. (2013), negative posttraumatic cognitions were associated with both PTSD and posttraumatic growth. Research suggests that changing posttraumatic cognitions in therapy is an effective tool to alleviate the symptoms of PTSD (Diehle et al. 2014; Schumm et al. 2015; Scher et al. 2017).

The type of traumatic experience might have effect on the structure of posttraumatic cognitions. Foa and Rothbaum (1998) suggested that negative cognitions about the self are characteristic for victims of sexual violence. It has been demonstrated that self-blame also plays important role in the processing of sexual violence (Halligan et al. 2003; Dunmore et al. 2001; Artime and Peterson 2015; Steine et al. 2017). The current study differentiated between women who had experienced sexual abuse and women who had been exposed to other types of trauma. International research shows that women have are overall at greater risk of developing posttraumatic disorders, even though men experience traumatic events more often (Ditlevsen and Elklit 2012; Kessler et al. 1995; Breslau et al. 1997). One explanation is that women develop more negative posttraumatic cognitions that men (Kucharska 2017a), but this relationship may also in part be associated with the fact that women experience sexual violence more often (Barlow and Cromer 2006; Cortina and Kubiak 2006; Kimerling et al. 2007), and this type of trauma is usually associated with greater severity of symptoms, as compared to the psychiatric symptoms following the non-sexual traumatic experiences.

The Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory was developed by Foa and colleagues (Foa et al. 1999) to measure three types of posttraumatic cognitions: negative cognitions about the self, negative cognitions about the world and the self-blame. A total of 36 items was included in the scale. Majority of items – 21 – assess the negative cognitions about the self, ‘cognitions about the world’ scale comprises seven items, and the ‘blame’ scale comprise a total of five items. It was demonstrated by the authors that the scale has a clear three-factor structure, has a good test-retest reliability and criterion validity. Blain et al. (2013) investigated the relationships between three subscales of the PTCI and the four-factor structure of PTSD and demonstrated that the scale is a good predictor of the severity of symptoms. Moreover, they showed that there are associations between specific types of cognitions and types of PTSD symptoms, i.e. cognitions about the self are linked with the re-experiencing symptoms. These results suggest that three-factor structure of the posttraumatic cognitions is not merely a statistical artifact. The three factor solution of the English version of the scale has also been supported in research conducted in Northern Ireland (Hyland et al. 2015). The three factor solution was also found in the Hebrew version of the tool tested in Israeli sample (Daie-Gabai et al. 2011); Spanish version (Andreu et al. 2016); Dutch version (Van Emmerik et al. 2006), German version tested in a clinical sample (Müller et al. 2010).

Aims of the Current Study

The aim of this project was to establish psychometric properties of the Polish version of the Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory, with reference to traumatic events of sexual and non-sexual type. This was a version of the questionnaire to be used in adult samples.

Method

Measures

Traumatic Events Inventory

A list of common potentially traumatic events based on the inventories used by Kessler and colleagues (Kessler et al. 1995), and Breslau and Kessler (2001). It consists of 10 items describing non-sexual traumatic events and 6 items referring to sexual trauma. Participants are asked to declare if something like this happened to them: (1) never; (2) in their childhood; (3) in adult life, but earlier than two years ago; (4) in the last two years. A set of continuous variables “Cumulative trauma” was also calculated: a number of different traumatic events of sexual type, number of different traumatic events on non-sexual type, total number of traumatic events. This questionnaire has previously been used in the research in Poland (i.e. Kucharska 2017b).

The Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (Foa et al. 1999)

A 36-item scale measuring beliefs related to a traumatic event a person was exposed to – all 36 items were translated into Polish. Three factors are assessed: negative views about the world, negative views about oneself, self-blame. The questionnaire was translated into Polish using the back-translation method – the translations from English to Polish and from Polish to English have been conducted by native Polish speakers; the comparison of two English versions was conducted by a native English speaker.

The Impact-Event Scale (Weiss and Marmar 1997)

A 22-item scale assessing the PTSD symptoms (as defined in the DSM-IV). Polish version was developed by Juczynski and Oginska-Bulik (2009) and has been used in research in Poland.

Participants and Procedure

The participants were recruited from general population (social networks, colleges, workplaces), there was also more targeted recruitment conducted via online chat rooms for victims of accidents, victims of violence, etc. In both cases a research participant was involved in advertising the study by distributing leaflets and posting information about the study on social media. The study was also advertised by the NGO’s that help women who had experienced violence. The potential participants were informed that the study involved questions about stressful, traumatic experiences and basic information about the study procedure was provided. This was an online study using the SurveyMonkey platform.

A total of 337 women completed the entire survey. All participants were Polish, residing in large Polish cities. 205 participants (60.5%) declared they had university education, 180 (38.6%) individuals declared they had high school education. The age range in the sample was 17–71, m = 33.34, sd = 11.93. Participants were asked to complete the PTCI twice: after completing the non-sexual part of the Traumatic Events Inventory and, once again, after completing the sexual part of the Traumatic Events Inventory. Therefore, two sets of variables were calculated: cognitions of non-sexual events and cognitions of sexual events. Only participants who had experienced a traumatic event of either non-sexual or sexual type were requested to complete a respective copy of PTCI. Of the sample, 216 participants completed PTCI related to non-sexual trauma, 168 completed the questionnaire related to sexual trauma. Presumably some of the participants had experienced both non-sexual and sexual trauma and, therefore, completed the PTCI twice. Nevertheless, the results for two types of trauma were analyzed separately.

Results

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted for cognitions of non-sexual events (n = 216) and sexual events (n = 168) separately. The factor structure of the scale was tested with exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. The reliability of the PTCI scales was assessed and the correlations between three subscales were examined. The correlations between the PTCI scales and other variables – exposure to traumatic events and the symptoms of PTSD – were also assessed in an attempt to establish criterion validity of the scale.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory Factor Analysis was used to test the three factor solution for the scale. Analyses were performed in SPSS Amos 25 Graphics software; each item was constrained to load on its designated factor. The model fit was poor for both the cognitions following the sexual trauma and cognitions following non-sexual trauma. Three factor solution for the posttraumatic cognitions following non-sexual trauma: Chi2 = 1689.55, df = 591, p < .000, RMSEA = .09, NFI = .75, TLI = .81, CFI = .82. Three factor solution for the posttraumatic cognitions following sexual trauma: Chi2 = 2071.87, df = 591, p < .000, RMSEA = .12, NFI = .71, TLI = .77, CFI = .77. The exploratory factor analysis indicated that, in the case of both sexual and non-sexual trauma, all items from the ‘blame’ scale loaded on Factor 1, so did the items from the ‘cognitions about the self’ items.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Since the confirmatory factor analysis did not yield conclusive results, exploratory factor analysis was performed using SPSS 24 software. A principal components method was used with the direct oblimin rotation. Exploratory factor analysis for the non-sexual events cognitions revealed a solution with 5 factors, where Factor 1 explained 49% of total variance. Items from the ‘cognitions about the self’ loaded heavily on this factor, and this subscale comprises the largest number of items. Factor 2 explained 7.9% of total variance with the items from the ‘cognitions about the world’ scale loading on this factor. Remaining three factors explained approximately 3% of total variance each. All items from the ‘blame’ scale were positively correlated with the Factor 3, items from the ‘cognitions about the world’ scale loaded on Factor 2. No items loaded uniquely on Factors 4 or 5; therefore, an extraction with a fixed number of three factors was carried out. This solution explained 61.23% of total variance, with Factor 1 explaining 49.47%, Factor 2–7.99%, Factor 3–3.76%. The pattern matrix is presented in Table 1. All items from the ‘cognitions about the self’ loaded highly on Factor 1, four items from this subscale (16, 17, 28, 32) also loaded high on factor 3. As for the ‘cognitions about the world’ subscale, all eight items loaded on Factor 2, with item 23 having moderate associations with factors 1 and 2. All five items from the ‘blame’ subscale laded highly on Factor 3, they did not load on any other factors. Those results show that the three factor solution is fairly suitable in the case on cognitions of non-sexual events.

Factor analysis was also carried out for the posttraumatic cognitions related to the sexual events. A solution with three fixed factors explained 68.56% of total variance, with Factor 1 explaining 55.52%, Factor 2: 8.91%, Factor 3: 4.11%. The pattern matrix is presented in Table 2. Factor loadings were similar as in the case of cognitions of non-sexual events, with all items from the ‘cognitions about the self’ subscale loading on Factor 1 (and three of them – 2, 26, 35 – also loading on a different factor). All eight items referring to ‘cognitions about the world’ loaded Factor 2, and again item 23 (“I can’t rely on other people”) leaded moderately Factors 1 and 2. All five items from the ‘blame’ subscale laded highly on Factor 3, they did not load on any other factors.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlational Analyses

Descriptive statistics for both groups, as well as results of the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality, are presented in Table 3. Since some support for the three factors solution was found in the exploratory factor analysis, the following calculations were performed for three separate subscales as well as for the whole scale. In the case of both non-sexual and sexual events, the scale of ‘cognitions about the world’ only followed the normal distribution. All other scales were positively skewed and, apart from the total result for sexual events, platykurtic. Reliability coefficients (α – Cronbach) for all scales are also presented in Table 3. Exceedingly high levels of reliability have been demonstrated, this applies to the overall scores for the whole PTCI scale and to all three scales representing three types of cognitions. Fairly strong positive correlations between the subscales were found:

-

Non-sexual events: ‘self’ – ‘world’ r = .61, p < .001; ‘self’ – ‘blame’ r = .73, p < .001; ‘world’ – ‘blame’ r = .47, p < .001.

-

Sexual events: ‘self’ – ‘world’ r = .62, p < .001; ‘self’ – ‘blame’ r = .78, p < .001; ‘world’ – ‘blame’ r = .55, p < .001.

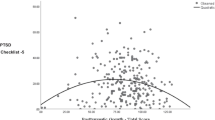

High, positive correlations were found between all scales of PTCI and the symptoms of PTSD (Table 4). As for the relationships between the cumulative traumas (number of different traumatic events of (1) sexual type, (2) non-sexual type or (3) both types of events) and the posttraumatic cognitions, weak positive correlations were found for both non-sexual and sexual events.

Discussion

The Polish version of the PTCI had fairly good psychometric properties in the case of both non-sexual and sexual traumatic events. Good criterion validity was demonstrated, as all three types of posttraumatic cognitions were highly correlated with the symptoms of the posttraumatic stress disorder. Moreover, posttraumatic cognitions were correlated with the number of different types of traumatic events the person has experienced, suggesting that there is an association between multiple trauma and development of negative cognitions. Some evidence to support the three factor solution was found: the pattern of results of exploratory factor analysis - as well as correlations with the symptoms of PTSD – provided support for this solution. However, in the case of cognitions associated with both sexual and non-sexual events, high positive correlations were found between the three subscales. This applies mostly to the correlation between negative cognitions about the self and self-blame. Correlation coefficients were slightly higher in the case of sexual traumatic events – however, values of all coefficients were lower that.80. Correlations between subscales obtained in this study are higher than the ones reported by Blain and colleagues (Blain et al. 2013) and results obtained in the validation of the Hebrew adaptation of the questionnaire (where the correlation coefficient for the cognitions about the self and blame was r = 0.32, p < 0.001; Daie-Gabai et al. 2011). However, results from this study are comparable with the results from the validation within a Northern Ireland sample (Hyland et al. 2015), where high correlations between the subscales were also demonstrated. In the current sample several items from the ‘Cognitions about the world’ and ‘Blame’ scales loaded on two factors: their respective factors and Factor 1, which represented the ‘Cognitions about the self’ scale. The confirmatory factor analysis showed that the factorial models did not fit the data well, but support for the three factorial solution was found in the exploratory factor analyses: in the case of both non-sexual and sexual traumatic events, the items loaded on their designated factors highly. Also, no items loaded uniquely on any factors besides 1, 2 and 3. The conclusion is that there is evidence to support the original structure of the tool and it might be justified to use both the total scores in the studies in Polish samples as well as the results for the three independent subscales. The major limitation of the current project was the sampling – a convenience sample from general population was used. It is advisable to test the psychometric properties of the scale in a clinical sample in the future. Also, the sample in this project consisted only of women; it is not clear whether the results can be generalized to men. A number of different traumatic events a person had experienced was assessed, but severity and duration of trauma were not – these variables could potentially also be associated with the level of posttraumatic cognitions.

References

Andreu, J. M., Peña, M. E., & de La Cruz, M. Á. (2016). Psychometric evaluation of the posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI) in female survivors of sexual assault. Women & Health, 57(4), 463–477.

Artime, T. M., & Peterson, Z. D. (2015). Feelings of wantedness and consent during nonconsensual sex: Implications for posttraumatic cognitions. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy, 7(6), 570–577.

Barlow, M. R., & Cromer, L. D. (2006). Trauma-relevant characteristics in a university human subjects pool population: Gender, major, betrayal, and latency of participation. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(2), 59–75.

Barton, S., Boals, A., & Knowles, L. (2013). Thinking about trauma: The unique contributions of event centrality and posttraumatic cognitions in predicting PTSD and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(6), 718–726.

Beck, J. G., Jones, J. M., Reich, C. M., Woodward, M. J., & Cody, M. W. (2015). Understanding the role of dysfunctional post-trauma cognitions in the co-occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder and generalized anxiety disorder: Two trauma samples. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 70, 23–31.

Blain, L. M., Galovski, T. E., Elwood, L. S., & Meriac, J. P. (2013). How does the posttraumatic cognitions inventory fit in a four-factor posttraumatic stress disorder world? An initial analysis. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy, 5(6), 513–520.

Breslau, N., Davis, G. C., Andreski, P., Peterson, E. L., & Schultz, L. R. (1997). Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 1044–1048.

Breslau, N., & Kessler, R. C. (2001). The stressor criterion in DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder: an empirical investigation. Biological Psychiatry, 50(9), 699–704.

Cortina, L., & Kubiak, S. (2006). Gender and posttraumatic stress: Sexual violence as an explanation for women’s increased risk. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115, 753–759.

Daie-Gabai, A., Aderka, I. M., Allon-Schindel, I., Foa, E. B., & Gilboa-Schechtman, E. (2011). Posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI): Psychometric properties and gender differences in an Israeli sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(2), 266–271.

Diehle, J., Schmitt, K., Daams, J. G., Boer, F., & Lindauer, R. J. L. (2014). Effects of psychotherapy on trauma-related cognitions in posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(3), 257–264.

Ditlevsen, D. N., & Elklit, A. (2012). Gender, trauma type, and PTSD prevalence: A re-analysis of 18 Nordic convenience samples. Annals of General Psychiatry, 11(1), 26.

Dunmore, E., Clark, D. M., & Ehlers, A. (2001). A prospective investigation of the role of cognitive factors in persistent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after physical or sexual assault. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39(9), 1063–1084.

Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319–345.

Foa, E. B., & Riggs, D. S. (1993). Post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims. In J. Oldham, M. B. Riba, & A. Tasman (Eds.), American psychiatric press review of psychiatry (Vol. 12, pp. 273–303). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Foa, E. B., & Rothbaum, B. A. (1998). Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD. New York: Guilford Press

Foa, E. B., Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Tolin, D. F., & Orsillo, S. M. (1999). The posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI): Development and validation. Psychological Assessment, 11(3), 303–314.

Halligan, S. L., Michael, T., Clark, D. M., & Ehlers, A. (2003). Posttraumatic stress disorder following assault: The role of cognitive processing, trauma memory, and appraisals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(3), 419–431.

Hyland, P., Murphy, J., Shevlin, M., Murphy, S., Egan, A., & Boduszek, D. (2015). Psychometric properties of the posttraumatic cognition inventory within a Northern Ireland adolescent sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54(4), 435–449.

Juczynski, Z., & Oginska-Bulik, N. (2009). Pomiar zaburzen po stresie trauamtycznym. Psychiatria, 6(1), 15–25.

Kessler, R., Sonnega, A., Bromet, A., Hughes, M., & Nelson, C. (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 1048–1060.

Kimerling, R., Ouimette, P., & Weitlauf, J. C. (2007). Gender issues in PTSD. In M. Friedman, A. Resick, & T. Keane (Eds.), Handbook of PTSD. Science and practice (pp. 207–228). New York: The Guilford Press.

Kucharska, J. (2017a). Sex differences in the appraisal of traumatic events and psychopathology. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy, 9, 575–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000244.

Kucharska, J. (2017b). Religiosity and the concept of god moderate the relationship between the type of trauma, posttraumatic cognitions, and mental health. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2017.1402399.

Müller, J., Wessa, M., Rabe, S., Dörfel, D., Knaevelsrud, C., Flor, H., Maercker, A., & Karl, A. (2010). Psychometric properties of the posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI) in a German sample of individuals with a history of trauma. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy, 2(2), 116–125.

Samuelson, K. W., Bartel, A., Valadez, R., & Jordan, J. T. (2016). PTSD symptoms and perception of cognitive problems: The roles of posttraumatic cognitions and trauma coping self-efficacy. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000210.

Scher, C. D., Suvak, M. K., & Resick, P. A. (2017). Trauma cognitions are related to symptoms up to 10 years after cognitive behavioral treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy, 9, 750–757. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000258.

Schumm, J. A., Dickstein, B. D., Walter, K. H., Owens, G. P., & Chard, K. M. (2015). Changes in posttraumatic cognitions predict changes in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms during cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(6), 1161–1166.

Steine, I. M., Winje, D., Skogen, J. C., Krystal, J. H., Milde, A. M., Bjorvatn, B., Nordhus, I. H., Grønli, J., & Pallesen, S. (2017). Posttraumatic symptom profiles among adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse: A longitudinal study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 67, 280–293.

Van Emmerik, A. A. P., Schoorl, M., Emmelkamp, P. M. G., & Kamphuis, J. H. (2006). Psychometric evaluation of the Dutch version of the posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(7), 1053–1065.

Weiss, D., & Marmar, C. (1997). The impact of event scale -revised. In J. Wilson & T. Keane (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Guildford.

Zang, Y., Gallagher, T., McLean, C. P., Tannahill, H. S., Yarvis, J. S., & Foa, E. B. (2017). The impact of social support, unit cohesion, and trait resilience on PTSD in treatment-seeking military personnel with PTSD: The role of posttraumatic cognitions. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 86, 18–25.

Funding

The study was funded by the Regent’s University London research fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The author has no conflict of interest to disclose.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kucharska, J. Validation of the polish version of the posttraumatic cognitions inventory. Curr Psychol 40, 611–617 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9963-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9963-y